Comments

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)

Grazed on the ear.

I can think of no worse contrast than Biden's campaign trying to talk up his "decent functioning," at his "big boy press conference," where he still managed to call his VP "Trump" and introduce Zelensky as "Putin" and Trump pumping his fist to the crowd after being shot at.

Maybe this will convince people that a viable candidate is needed (meaning probably not Harris). I doubt it. -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

The conservation part was the only reason I remembered it TBH.

I agree that material implication has problems, but if you want a tidy, "algorithmic" system, then these sorts of problems are inevitable.

Or one that isn't horrifically complex. I actually think that is what gets people more than the "paradoxes of implication." People can learn that sort of thing quite easily. What seems more confusing is the way in which fairly straightforward natural language arguments can end up requiring a dazzling amount of complexity to model. -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?A = There are vampires.

B = Vampires are dead.

Not-B = Vampires are living.

As you can clearly judge, this truth table works with Ts straight across the top, since vampires are members of the "living dead." Fools who think logic forces them to affirm ~A are like to end up missing all their blood.

You might be interested in relevance logic, which tries to deal with the paradoxes of material implication: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/logic-relevance/

There is a section in Tractatus where Wittgenstein declares that belief in a causal nexus is a "superstition" and holds up logical implication as sort of the "real deal." I think this is absolutely backwards. We come up with the idea of logical implication from experience, from the way the world works. This is mistaking an abstraction for reality, and this is ultimately where I think the discomfort with the paradoxes come from.

There is some interesting stuff on modeling relevance logic in terms of information theory I've seen but I forget where I found it. -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

Let A = "Unenlightened's testimony is unreliable"

Let B = "Unenlightened tells the truth"

not B ="Unenlightened does not tell the truth"

↪Count Timothy von Icarus might note that ↪unenlightened's testimony is reliable

That's a cute one. It seems to trade off the ambiguity of translating statements into logic. Obviously when we say someone's testimony is "unreliable" what we mean is that some of their statements are true and some are not true. But there is nothing contradictory about A implying some B are C and A also implying that some B are not C, and so we won't be forced to deny A.

I think one of the challenges inherit with formal logic is that even fairly straightforward arguments of the sort you might find on some science blog or op-ed end up requiring all sorts of stuff to formally model correctly: counterfactuals, modality, temporality, etc. It gets very complex very quickly.

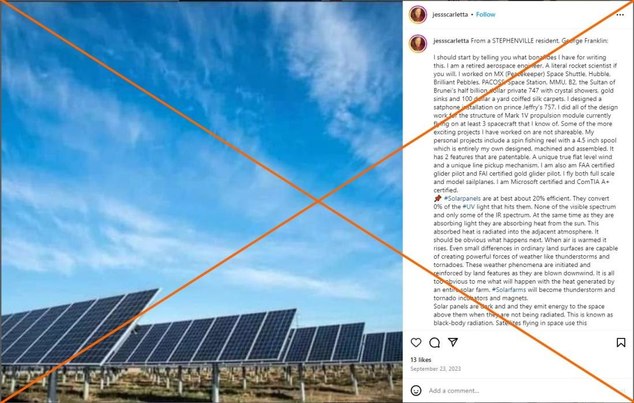

It's even hard with comically bad arguments like the pic below. Premises like "solar panels reflect more heat than grass or trees," and "small changes in ground temperature can cascade into large changes in weather systems, including tornado formation," are all true, but the conclusion that solar farms are "tornado incubators" is still baseless.

-

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

I don't think so. Or I would like to know of a system or approach that supports it.

This is Kreeft and Dougherty's argument for the superiority of Aristotlean logic for many common uses (evaluating writing, rhetoric, scientific arguments, etc.)

See: https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/916812

It seems to me though that the real benefit is that the "three acts of the mind," end up enforcing a sort of realism on the interpretation of syllogisms. -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

The way you would usually use it in any sort natural language statement would be to say: "Look, A implies both B and not-B, so clearly A cannot be true." You don't have a contradiction if you reject A, only if you affirm it.

This is a fairly common sort of argument. Something like: "if everything Tucker Carlson says about Joe Biden is true then it implies that Joe Biden is both demented/mentally incompetent and a criminal mastermind running a crime family (i.e., incompetent and competent, not-B and B) therefore he must be wrong somewhere." -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

Material implication is often written in natural language as:

If A, then B

Or

A implies B

But they aren't perfect translations because all sorts of shit that sounds very dumb in natural language flies in symbolic logic. E.g. "if Trump won the 2020 election then we would have colonized Mars by now."

Anything follows from a false antecedent, so anything would be "true" following the claim that Trump won the 2020 election, since he didn't. But obviously in natural language the if/then here is talking about a counterfactual claim, and to say that if x had happened then y and not-y is (normally) nonsense talk. -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?Related:

...but we can also usefalse propositions in good reasoning. Since a false conclusion cannot be logically proved from true premises, we can know that if the conclusion is false then one of the premises must also be false, in a logically valid argument. A logically valid argument is one in which the conclusion necessarily follows from its premises. In a logically valid argument, if the premises are true, then the conclusion must be true. In an invalid argument this is not so. "All men are mortal, and Socrates is a man, therefore Socrates is mortal" is a valid argument. "Dogs have four legs, and Lassie has four legs, therefore Lassie is a dog" is not a valid argument. The conclusion ("Lassie is a dog") may be true, but it has not been proved by this argument. It does not "follow" from the premises.

Now in Aristotelian logic, a true conclusion logically follows from, or is proved by, or is "implied" by, or is validly inferred from, only some premises and not others. The above argument about Lassie is not a valid argument according to Aristotelian logic. Its premises do not prove its conclusion. And common sense, or our innate logical sense, agrees. However, modern symbolic logic disagrees. One of its principles is that "if a statement is true, then that statement is implied by any statement whatever." Since it is true that Lassie is a dog, "dogs have four legs" implies that Lassie is a dog. In fact, "dogs do not have four legs" also implies that Lassie is a dog! Even false statements, even statements that are self-contradictory, like "Grass is not grass," validly imply any true conclusion in symbolic logic. And a second strange principle is that "if a statement is false, then it implies any statement whatever." "Dogs do not have four legs" implies that Lassie is a dog, and also that Lassie is not a dog, and that 2 plus 2 are 4, and that 2 plus 2 are not 4.

This principle is often called "the paradox of material implication." Ironically, "material implication" means exactly the opposite of what it seems to mean. It means that the matter, or content, of a statement is totally irrelevant to its logically implying or being implied by other statements. Common sense says that Lassie being a dog or not being a dog has nothing to do with 2+2 being 4 or not being 4, but that Lassie being a collie and collies being dogs does have something to do with Lassie being a dog. But not in the new logic, which departs from common sense here by totally sundering the rules for logical implication from the matter, or content, of the propositions involved. Thus, the paradox ought to be called "the paradox of wort-material implication. The paradox can be seen in the following imaginary conversation:

Logician: So, class, you see, if you begin with a false premise, anything follows.

Student: I just can't understand that.

Logician: Are you sure you don't understand that?

Student: If I understand that, I'm a monkey's uncle.

Logician: My point exactly. (Snickers.)

Student: What's so funny?

Logician: You just can't understand that.

The relationship between a premise and a conclusion is called "implication," and the process of reasoning from the premise to the conclusion is called "inference" In symbolic logic, the relation of implication is called "a tnith-functional connective," which means that the only factor that makes the inference valid or invalid, the only thing that makes it true or false to say that the premise or premises validly imply the conclusion, is not at all dependent on the content or matter of any of those propositions, but only whether the premise or premises are true or false and whether the conclusion is true or false.

...Logicians have an answer to the above charge, and the answer is perfectly tight and logically consistent. That is part of the problem! Consistency is not enough. Logic should be not just a mathematically consistent system but a human instrument for understanding reality, for dealing with real people and things and real arguments about the real world. That is the basic assumption of

the old logic.

Peter Kreeft & Trent Dougherty - Socratic Logic

-

Sartre's 'bad faith' Paradox

Yes indeed. I do think the problem of diagnosing bad faith "from the outside," is related to the fact that no determinant end lies behind action though. Because of this there is no external demarcation accessible to us by which to judge the issue.

I do believe he shifted his philosophy in response to this sort of issue though. I recall reading that his later stuff has it that we can determine bad faith in oppressive actions. Our freedom ultimately entails an interest in others freedom (for broadly Hegelian reasons). I'm not really super familiar with this interpersonal/social turn though. This also helps get away from the idea that the oppressed are involved in a sort of bad faith, which seems a bit off in at least some cases. -

How do you interpret nominalism?

Well this is tricky. Plato, Aristotle, or Augustine are aware that Scythians and Egyptians call things by different names, that people can make up new names for things, that language is learned, and that language is a "social practice."

What makes them realists is the fact that they believe that universals like "triangularity," exist tout court; the names are invented to name the universals. For Aristotle, the universals only exist where they are instantiated, e.g. in triangular things. For Plato they exist outside of individual instances in a way, although not in the way that individual objects exist. For Augustine the sign directs us to the universal in the Logos, and even individual instantiations of things can be thought of as signs of a sort, all effects being signs of their causes and the world itself being both a sign and in a way sacramental (an outward sign of inward things).

Likewise, the nominalist will generally allow that there is some "real difference," between tables and chairs or tigers and ants, etc. If there wasn't a difference there would be no use in making up different words for them and we wouldn't be able to tell which words apply to which things.

More modern nominalists will often say something like: the names are names for "sense data," as opposed to "properties of things." E.g., Locke would have it that universals like "red" only apply to "secondary properties," which only exist in minds, or we could consider the Kantian noumenal/phenomenal distinction which gets roped in here at times.

And then more recently you get tropes. Trope theories vary a lot, but some seem to me like essentially realism for people who don't want to say they are realists lol. -

How do you interpret nominalism?

Reminds me of the famous quip in Chesterton's Orthodoxy:

Then there is the opposite attack on thought: that urged by Mr. H.G.Wells when he insists that every separate thing is "unique," and there are no categories at all. This also is merely destructive. Thinking means connecting things, and stops if they cannot be connected. It need hardly be said that this scepticism forbidding thought necessarily forbids speech; a man cannot open his mouth without contradicting it. Thus when Mr. Wells says (as he did somewhere), "All chairs are quite different," he utters not merely a misstatement, but a contradiction in terms. If all chairs were quite different, you could not call them "all chairs."

There are materialist realists. Some people posit that the are only a few universals, e.g. various flavors of quark, lepton, etc. -

Sartre's 'bad faith' Paradox

The "facticity" of our being can't spring up uncaused, e.g. our being French, or 22 years old, etc. This would be quite a thing to try to argue. Nor can choices spring up wholly "uncaused," since choices arise in the context of the contents of phenomenal awareness, and to deny that these are "caused" by what lies external to us would essentially be to deny the external world (or any link to it at least). It's purpose and meaning that are springing forth posterior to these—meaning and purpose have no weight save our own embrace of them (at least for the early Sartre; in his late work he backs away from his maximalist positions significantly from what I understand). This is why there is no way to determine good or bad faith "from the outside," because there is no rational nature (scholastic human essence) posterior to our values, purposes, and projects.

I'm sympathetic to parts of the description of bad faith, since it seems to get a core element of reflexive freedom—the idea that we have to be aware of what we are choosing and of our own choosing (and thus our responsibility). I'm also sympathetic to the parts that come down from Kierkegaard, but not necessarily how they get reframed in terms of freedom as a "transcending our material conditions." In Kierkegaard, (as also in Plato, most of the classical tradition, and Hegel) it is our relationship to the infinite (Good) that allows us to transcend the given, i.e., "what we already are."

Personally, I think Kierkegaard represents a degradation of this tradition to some extent, even if his presentation is superior to Hegel's, since the sense in which reason is part of what allows for this sort of transcendence seems to get lost. His focus on the "subjective" always seemed to me to be raising practical/moral reason up over and against theoretical reason. For Kierkegaard, theoretical reason seems at times to become a limit on freedom, e.g. in "Passion and Paradox." In the early Sartre, the infinite Good disappears as the source of transcendence as well (whereas reason's search for Truth is already gone, and Beauty has gone with these). The result is that transcendence seems to emerge from a bare haecceity, essenceless existence, sheer potency. But rather than safeguarding freedom, this would seem to simply collapse value and meaning into what is ultimately arbitrary—it cannot be grounded in a "rational nature" (essence) that seeks some determinate end because freedom is defined in terms of indeterminacy— potency over act.

And this crops up in early attempts to deal with Hegel's Lord-Bondsman dialectic. For Hegel, there is a determinant rational end, Spirit's fulfillment as "the free will that wills itself." Kick this end out and what is left? (Nothing says Hegel in PR §5/§15). The human inheritly demands thymos because...? It can't be because of their (or Spirit's) "rational nature," as in Hegel.

From what I understand it was working over this dialectical, conversations with de Beauvoir (who I think has a much better understanding here and expands the dialectical in useful ways, e.g. gender relations), and a growing recognition of the need for a dimension of social freedom/recognition that moved Sartre away from the early "absolute freedom." I am less familiar with this later stuff, but from what I've read it seems to default on the "existence precedes essence," view (or at least radically alter it), and IIRC he did indeed reject that specific formulation eventually. But I was thinking primarily of that early view with the comments on freedom collapsing into arbitrariness.

I think there are other problems too. The phenomenological experience of volition does not seem to always imply any real choice. Some stroke victims describe experiencing everything they observed appearing voluntary, e.g. the leaves blow across the lawn and they feel like they willed for then to move and made them move. So, to the extent the plausibility of such freedom relies on this sort of fallible presentation of volition to awareness, it seems open to critique.

Moreover, it seems to set freedom against the view of Russell and the other reductionists of Sartre's era (but for the wrong reasons). If freedom in choice is defined in terms of choice springing from potency then determinism still seems to be a threat. (Indeed, the early near Stoic view still seems to require a sort of dualism to maintain in light of the science of cognition). I'd trace the problem here back to Kierkegaard booting theoretical reason from a determinant role in freedom (Nietzsche too). No longer is determinism seen as in a way conducive (or even essential) to freedom, in that it allows theoretical reason to give us a sort of "causal mastery" of the world through techne (e.g. Leibniz's invocation of PSR in defense of free will). Instead we have to keep retreating posterior to the findings of theoretical reason (the sciences) to defend freedom (a freedom which is increasingly contentless).

Well, I've probably gone on too long with not very well organized insomnia thoughts, but perhaps that gives you an idea.

Edit: And I'm aware that later work suggests that oppression might always be a sort of bad faith, but as near as I can tell this is defaulting on the original formulation re essence. -

Sartre's 'bad faith' Paradox

Of course he doesn't, that would be silly. His point is posterior to those things.

The essential thing is contingency. I mean that one cannot define existence as necessity. To exist is simply to be there; those who exist let themselves be encountered, but you can never deduce anything from them. I believe there are people who have understood this. Only they tried to overcome this contingency by inventing a necessary, causal being. But no necessary being can explain existence: contingency is not a delusion, a probability which can be dissipated; it is the absolute, consequently, the perfect free gift. All is free, this park, this city and myself. When you realize that, it turns your heart upside down and everything begins to float...

It's the Good above all that he insists floats totally free. But the Good is presumably that by which we act if we act "for any reason at all."

Anyhow, Alvin Plantinga, who I don't much care for but who is a great logic chopper took up your question in a fairly well received book. His conclusion was pretty much that we cannot tell who is acting in good faith. Good faith doesn't suppose any sort of particular actions, e.g., "don't kill babies for fun." Sartre knows it when he sees it; in the waiter, in the girl on a date, but in these cases he envisages "seeing through their eyes," to a degree. -

Sartre's 'bad faith' Paradox

By realizing Sartre is simply wrong. Human beings have an essence, a nature. To ignore this is simply to be ruled by something that lies outside one's grasp of reality, to be determined by ignorance. Our actions do not spring from the aether uncaused, nor do we.

Even if they did, acts determined by nothing but "bare will"—pure potency—would ultimately be arbitrary and random anyhow. I am not sure if any definition of freedom in terms of potency—sans any notion of determinant good towards which rational nature's strive—avoids collapsing into mere arbitrariness. -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

Yeah, it's not a contradiction, but the final row of the truth table for p→q ∧ p → ¬q is the same p → q ∧ ¬q for all values of p and q. -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

That's not the same as "(A implies B) and (A implies not-B)" -- that'd be "(A implies (B and not-B)).

Are they not? First and last rows of the truth tables are all the same. Seems logically equivalent to me. -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?Can anyone think up a real world example where you would point out that A implies both B and not-B except for saying something along the lines of:

"A implies B and not-B, therefore clearly not-A." -

An Argument for Christianity from Prayer-Induced Experiences

(3) If praying induces experiences for a biological reason, then prayer-induced experiences are not observations of reality but hallucinations.

I don't get this one. When I look outside my house I experience seeing my car for "biological reasons," but this doesn't undermine my claim that my car is "really there." Presumably when God makes people have visions God would interact with their biology (barring some sort of dualism, but the Bible doesn't lean in this direction).

It is comical that God intentionally bothers to mysteriously appear to random people at random times and yet stays quiet when a little Nepali child is being ripped to shreds by a Bengali tiger. Curing children from cancer is somehow a violation of free will, but turning a little lump of blood into liquid like in the "miracle" of Saint January doesn't violate free will at all, does it?

If cancer and tigers didn't exist couldn't you still make this same argument? What ratio of ills would need to be eliminated from the world to make it "good enough?"

Anyhow, I am not sure what life looks like without suffering, what natural selection looks like without disease or negative mutations, or what the evolution of Earth looks like without earthquakes, volcanoes, or floods.

At any rate, I'm not sure if the disappearance of tiger attacks and cancer from the world would constitute good evidence for God. If they did, would a 50% reduction in cancer rates work as well? Only 10%? Providence seems to have taken care of the tigers since are tending towards extinction in the wild. -

Do I really have free will?

Are you suggesting that we ignore scientific approaches that aren’t ‘mature’?

No, and diversity doesn't "bother me." I said it doesn't make sense to try to define "mental life" and "freedom" in terms of particular neurological theories, when such theories remain highly speculative and the point being made doesn't involve the particular details of any of them.

I think we are just talking past each other because enactivism is much broader than accounts that try to posit some specific 'mechanism' by which first person experience emerges. I may have misunderstood what you were asking about in the first place.

To my mind, representationalism, indirect realism, enactivism, etc. are all broad enough to allow us to be much more confident in our analysis than something very specific like brain wave oscillation theories or quantum conciousness or what have you. -

The Greatest Music

political prejudice, not philosophical prejudice.

I don't know how easy it is to separate these. Locke for instance is probably motivated in his rejection of innate ideas and the Cambridge Platonists by political concerns.

Likewise, the idea that "x is social constructed," in turn means "x is arbitrary and could potentially take any other form we can imagine for it," seems to flow from a particular notion of freedom as indeterminate potency. Politics is always lurking here on the fringes.

Plus, "philosophical bias," can be just as totalizing. Russell obviously had his greater "project" in mind when he made his arguments against causation. In some cases, his arguments look fairly polemical and spurious in retrospect, the "project" driving the analysis. -

The Greatest Music

That is not the result, it is the condition from within which we judge.

Right, but you seem to suggest that the "sound person" never gets outside this condition?

But then it seems that if the "sound people" claim that they have found a "better" (more good) way of dealing with this situation they will have to claim to know something of goodness and what is better. If they're opinions are of equal merit with everyone else's then why would it be profitable to listen to them?

But that is not all he is doing. Aristotle says the rhetoric is the counterpart to dialectic. The sophists are not the only ones who attempt to persuade us, and it is quite evident that myths can be persuasive. In some causes they can be so persuasive that there are those who believe them to be the truth.

Ok, so suppose Socrates convinces Glaucon that the Good is such and such and that it is better to be just, but to be seen as unjust, rather than to be unjust but seen as just. His myth has successfully changed Glaucon's mind. This leaves the question: "why is it good for Glaucon to believe what Socrates' wants him to believe?" If Socrates is ignorant of the Good, why should it benefit Glaucon to be influenced by Socrates' myths?

It's not clear to me that it does. If Socrates, in his ignorance, is wrong about the Good, then it seems he might simply be harming Glaucon by convincing him to follow Socrates into his particular brand of ignorance. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

A number of your core points agree with my understanding. The Good is ultimately that towards which all rational natures strive, so there aren't so much "multiple final ends," as there are "multiple conceptions on how best to achieve the Good." E.g., the person who advances towards what they think will bring annihilation does so because they think annihilation will be "good" in a sense.

Aristotle has it that the Prime Mover must be an intellectual nature. Where Neoplatonism saw its most expansive development was in the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic tradition, and there the One was always a person (or three persons of one substance). But these developments (which predate, and to some degree influenced Plotinus via folks like Philo, Clement, and Origen—"Middle Platonists") throw in another sort of difficulty in the form of the Analogia Entis. Here, all predication involving infinite being and the Divine Nature threatens another sort of consuming equivocity; at best we can hope for analogy.

But if we consider the Platonic vision of Calcidius, the harmoniously ordered cosmos of Dante, or the "symphony of the spheres," heard by Cicero's Scipio, we seem to be led back to the ends pursued by mindless entities in that these are ultimately ordered to a greater end by the "super intellect," of the super intelligible (e.g. Pseudo Dionysus). The ultimate ordering of finite ends turns on a single point, God "boiling over in love," (Meister Eckhart) and producing a "moving image of eternity," in which the creature can become free and freely pursue the Good.

Of course, the "free creatures" are part of this cosmic ordering, and themselves strive towards the same Good. And to the extent they are free, they pursue this Good as opposed to some merely relative or counterfeit good. So while we have three apparent "levels" here: mindless thing's finite ends, the ends of finite agents, and the Good itself to which all existence is orderer and in which it "moves and has its being" (Book of Acts), they all end up being deeply related.

But I was thinking of the question more in terms of the modern "naturalistic" conception. Perhaps this is a bad frame from which to approach this question precisely because it seems to make the "ends" of "physical systems" and the "purposes" of agents either entirely equivocal, or else too univocal, the latter just collapsing into the former, agents themselves being mere "mechanism all the way down." -

The Greatest Music

Socrates turns from the problem of the limits of sound arguments to the soundness of those who make and judge arguments.

I know what a "sound argument" is in classical logic, I'm unsure what a "sound person" is. I would assume it's something like "being ruled by the rational part of the soul?"

But if the soundness of the person who judges arguments always only results in nescience and opinion, it's unclear to me what the benefit here is. Sound arguments are useful because they have clear terms, true premises, and valid conclusions, and thus tell us the truth of something. It seems that "sound people" in this case can never get to truth (or be sure that they have even if they do somehow attain to it), so the two are quite different.

So, when Nietzsche comes along and claims that "the rule of reason," and dialectical are both simply means for Socrates to carry out his ressentiment against a heroic society in which his weakness and ugliness preclude him from gaining status and power (Twilight of the Idols, "The Problem of Socrates," etc.) what's the response?

"Well Mr. Nietzsche, we both have opinions, and the truth about who is right cannot be discovered. Nonetheless, our mode of inquiry is superior."

Superior in virtue of what? Certainly not superior in virtue of leading to a greater knowledge of what is truly good.

And yet, he does care. The answer to that question matters to him

Yes, he cares because he hopes Socrates can answer this question, that he can show why we should prefer to be just. But if all Socrates can offer is "edifying myths" that try to prompt him towards justice (or rather, Socrates' idea of justice, which is mere opinion) then why exactly should Glaucon bother with such myths? Socrates has patently defaulted on attempting to explain why justice is good for the just person and has instead begun spinning stories to try to get people to go along with his preferred opinions like a sophist. Where is the benefit in following Socrates' stories or of being just? Surely Homer and Nietzsche's stories can make us feel as good, if not better. -

Do I really have free will?

Certainly, there are isomorphisms between leading theories of consciousness, but there are nonetheless many and it's not common to see conferences with 6+ different theories being advanced: HOT, various forms of CMU, (e.g., GWT), IIT, re-entry, Bayesian Brain theories, various quantum brain theories, biosemiotics versus pan-semiotics, recoveries of formal (and thus final) causation through thermodynamics, panpsychism, pancomputationalist spins on the aforementioned, etc. These theories are also often in conflict to some extent. For example, per pancomputationalism, everything can be thought of as a "computer" of sorts and so the special explanatory value of CMU becomes somewhat hazy.

TBH, I think the isomorphisms are more due to everyone working off the same suggestive research findings than all of these sharing some sort of deep connection.

I forget who it was, but I recall one conciousness researcher likening the field today to the vast proliferation of theories drawn up to explain the findings that led Einstein to GR/SR in physics. In a mature fields, people don't announce a new paradigm shift every year or so—evolutionary biology for example has one major power struggle that has slowly built around the same lines for decades now.

Of course, there are a great many partisans who claim that their camp has already solved problem, but they can't even seem to even convince their own teammates of this fact, let alone the other camps.

I would agree that challenges to representationalism have gained market share, but representationalism remains, I would guess, still a majority paradigm for looking at perception. Folks like Bickerton, Hoffman, etc. Even if it isn't, it's still a quite popular way to think about things. Vision in particular is very often described in this manner.

Hence, while I find this area interesting, I'm not sure it's a particularly profitable way to analyze freedom. I think it's enough to point out that an explanation of consciousness where our experiences and volitions have no causal role in our behavior faces a host of issues and shouldn't be assumed. Attempts to describe awareness in terms of neurology themselves seem prone to slipping into the mistake of positing that "brains = minds," which in turn abstracts the enviornment out of the analysis. But brains won't produce any conciousness if placed into the vast majority of environments that exist in the universe (e.g. the bottom of the sea or the surface of a star). -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

It seems easy to talk about ends, "biological function," constraints, or equilibrium in a way that doesn't require an agent. This is how a teleology of sorts if often still included in the natural sciences.

However, I think you raise an excellent point. Are these sort of "ends" univocally related to the "ends" or "purposes" of agents? I'm inclined to say the similarity is only analogous. It isn't completely equivocal, but it certainly isn't univocal either. -

The Greatest Music

Why would trying to know what is good but failing to do so teach you how to act good?

It may prevent you from acting unjustly or wrongly accusing others of acting unjustly.

If what you learn in your inquiries suggest you should do that perhaps. Many people have plumbed the depths of this question and determined that there is no such thing as "goodness" and thus that they should do whatever pleases them and is to their advantage.

But I suppose this brings up Glaucon's question in the Republic, why should we even care about being good or just? If we can't even know that we are being good or just, or what these things consist in, what would be the benefit to us? Why wouldn't it be enough just to have people think we're good and just?

If someone claims to know what is the Good, do you know, can you know, that she knows what is the Good?

This question seems pretty easy to answer if you have an idea of what goodness consists in, no? Otherwise, you might consider whether or not that person really pursues what they claim the good is. Whatever is truly good it seems should be choiceworthy, or else it hardly seems deserving of the name.

There seem to be many things that all (or at least most) people take to be good. Does that consensus amount to knowing what is the Good, or what goodness universally consists in, its essence?

Consider how well consensus works as a measure of truth for any other question in history: the nature of disease, the relationship between the Earth and the Sun, etc.

As a metric, it seems to be quite lacking. -

0.999... = 1If 0.9999 = 1 than it seems that 0.000...0001 should be equal to 0.

But now I think we'll all agree that as you divide a number by smaller and smaller numbers your output gets ever greater.

So:

1/0.1 = 10

1/0.0001 = 10,000, etc.

But since 0.00...001 = 0 and 1 / 0.000...001 = ∞ then 1/0= ∞.

Now it is also true that 4/0=∞ and 9.7181=∞. And with a little more leg work I shall demonstrate that all numbers are actually equal to each other. Multiplicity is mere illusion, a result of the Fall and Adam's sin.

:razz: :nerd: :up: :100: :heart: :strong: :strong: :strong: -

Do I really have free will?

But Hume and Kant showed there is no cause and effect - they are just constructions that might have nothing to do with the world in itself.

I mean, they claim to show these things. I think Hume is mostly engaged in elaborate question begging on this topic, and Kant's critical philosophy itself rests on dogmatic assumptions. But TBH, I find very little to like in early modern metaphysics in general. I take Hume mostly to be pointing out how his time's conceptions of causation and "natural laws," is flawed, but not much more than that.

Kant meanwhile I seen as hopelessly hung up on the weird early modern fascination with knowledge of "things-in-themselves," as the paradigmatic gold standard of knowledge, rather than what it actually is, irrelevant and epistemicaly inaccessible—a comedy of errors leading back through Locke and on to Bacon. But that's just me; there is other good stuff in there outside the metaphysics anyhow.

I'm not really sure what sort of difference this sort of theorizing is supposed to make. This is an area of inquiry where there is a great amount of disagreement—an area that seems to be getting less, not more unified each decade. I think it's enough to point out that it's implausible to say that people never eat the food they choose to eat because it tastes good, don't have sex because it feels good, or that their self-conscious reflections never affect how they act.

Causal closure itself isn't based on any deep theory of how physics works. It's based on a few presuppositions (probably bad ones) about how thing's properties must inhere in what they are composed of. It's enough to show that accepting it leads to serious explanatory problems vis-á-vis psychophysical harmony and serious epistemic issues.

Maybe these problems can be worked out. As it stands though, there is no good reason to "assume it's true until proven otherwise." The same is true of smallism in general. But it's commonly asserted that smallism and causal closure is "how science says the world is," with the assertion being precisely that it should be assumed true until proven otherwise, nevermind that the basics of chemistry still haven't been reduced to physics over a century on, etc. -

The Greatest Music

(Phaedo 97b-d)

I am at a loss for how the passage you cite is supposed to support your claim. In context, the passage you cite is Socrates discussing his initial fascination with Anaxagoras' materialism, and how Socrates claims to have misunderstood the theory. Socrates was hoping Anaxagoras was going to give him some sort of explanation of things in terms of their telos and what is best—an explanation of the material world of becoming in these terms. He ultimately writes off the materialists because they seem to be missing an explanation of final causes.

Having some idea of what is better is not knowing what is better. It is an opinion or belief. He could be wrong:

Ok, is everyone equally likely to be wrong? Must we be equally skeptical of all claims about what is good? Might we has well question if this "questioning" really has any value or if it's just a way for egg heads to waste their time?

It is the question of what is better that is at issue. It involves deliberation about opinions about what is best

But such deliberations never move one past a state of skeptical nescience? What exactly is the benefit of "trying your best" to understand what justice is? -

Do I really have free will?I feel like this is perhaps the area of philosophy most rife with confusion. How exactly would "undetermined" actions be free? If a choice is "determined by nothing" then it is essentially arbitrary and random and in no sense would such a choice be "ours."

Yet when we talk about freedom we tend to think that we are speaking of our ability to make choices based on what we believe, what we feel, or "the type of person we are." We would like to think things like: "I married my spouse because I love them, and I love them because of who they are." Yet for this to be true it has to be the case that our spouse, and "who they are," conditioned our actions.

At the same time, indeterminism throws up another threat to freedom on the other side of the equation as well. If our actions didn't have determinant effects, if when we chose to do something we could have no clear idea what the outcome of that action would be, then we would lack the freedom to actualize any plan we had for our lives. For example, if putting my infant son into his crib might as likely cause him to burst into flames as to let him sleep then I am not really free to "be a good parent."

Thus, some form of determinism would seem to be a prerequisite for our actions to be "ours" and for our actions to embody our will (i.e. producing consequences we want to produce).

So when people talk about freedom in terms of "science" what they really seem to be asking about is not so much determinism but the principle of causal closure. The question can be reframed as: "do my intentions and feelings play a causal role in my behavior? Does my self-conscious decision making process affect my choices? Do people have sex because it 'feels good' or is all feeling a mere 'epiphenomena' with no causal efficacy?"

Note that being "self-consciously self-determining" seems like it should be a matter of degree, not a binary state. No one creates themselves ex nihilo, but it seems like it might be possible for the behavior of any physical system to be more or less determined by what is external to it. If that system is conscious and thinks through decisions, it seems possible that this plays a role in that system's behavior. And since we can change our enviornment and shape it in ways that accord with our will (e.g. writing a post-it note to remind us to get milk) it's also unclear if we can simply throw up some sort of naive "body versus enviornment " dichotomy here to help determine what is "self-conscious self-determination," and what isn't.

Now under causal closure there is no freedom in this sense because the mental can never, upon violation of the principle, cause anything to happen. But there are lots of good reasons to think causal closure is an inaccurate picture of the world. For one, if it is true, then sex can never feel good and food can never taste good "because" it motivates us to engage in certain behaviors. All the evidence for how natural selection shapes our preferences suddenly becomes very hard to explain. If the mental NEVER has causal efficacy then it can never affect behavior and so natural selection can never select on the contents of phenomenal awareness. At the same time, "mental phenomena," would apparently be the lone, totally sui generis thing in our universe that exists but is causally insignificant.

Yet there is a great deal of evidence to the contrary here, not to mention that causal closure also brings with it a host of deep epistemic problems. At the same time, the resurrected 2,400 year old view that our world can be naively explained as "balls of stuff" bouncing around in a void is also a view that has some significant problems. Yet it's generally the desire to buy into this view that motivates advocates of causal closure in the first place.

I started reading it, but it basically seemed like a rehash of 1940s style atomism → determinism with causal closure → no free will arguments. Skimming ahead didn't make me want to keep going (neither did reviews, which sort of confirmed my suspicions). I was not impressed. Just from my notes:

"show me a neuron (or brain) whose generation of a behavior is independent of the sum of its biological past”

I mean, the idea that things are just "what they are made of," is a pretty bold metaphysical assumption, and I don't even know how well it holds up with majority opinion in physics/philosophy of physics these days (certainly there are lots of views that go against this sort of "building block" view). But aside from that, the argument seems to be that if there isn't magical uncaused action going on "in the brain" then freewill is impossible. This is at worst a strawman and at best a dramatic misunderstanding of how free will is generally discussed in contemporary philosophy.

But, like many eliminitivist texts, it seems to mistake complexity for good argument, and a deluge of empirical facts seems to do little more than muddy the waters. -

The Greatest Music

Socrates never abandons his pursuit of the good. It is not for him an intellectual puzzle to be solved. It is a way of life. The pursuit of the good is good not because the good is something we might discover. The pursuit of the good is ultimately not about knowing the good but about being good.

This seems to bring up some important questions:

How does one know if one is being good if one doesn't know what is good or in what goodness consists? Plato is often critical of the Homeric heros and offers Socrates up as a new sort of hero to supplant them. But to suppose that Socrates is more virtuous than Achilles, and that he makes a better role model, is seemingly to suppose something about goodness and what it consists in.

Likewise:

There are things that he thinks it is better to believe to be true even if they are not. The philosopher may object that she is interested in what is true, not in what seems to be true, and certainly not in making it seem to be true. But the truth is, there are things that we do not know to be true. Rather than this leading to nihilistic skepticism, in the absence of knowledge Socrates asks us to consider what it is that is best for us to believe as true. This not for the sake of the truth but for the sake of the soul.

If we are to believe things because doing so will make us better it seems that we need some idea of what "better" consists in. Why isn't it just honor and glory?

I think a major current that runs through dialogues is a sort of "meta-ethics," for lack of a better term. Plato is speaking to skeptics. "Perhaps you don't believe me on this or that, but look, here is the bare minimum you need to even be able to determine what is good, regardless of what that good turns out to be."

Being ruled by reason turns out to be a meta virtue. It's crucial to being able to inquire into what is truly virtuous in the first place. One needs the self-control, honesty, etc. to go out and discover the good. One needs to be able to inquire and debate in good faith. Likewise, the constellation of virtues associated with the "rule of reason," are essential to acting on anything one has learned about what is righteous, regardless of what that turns out to be.

But this isn't all Plato is doing. The dialogues aim at different audiences. This is the message to the skeptics. He has other things to say for people who have already started down this road and are ready to hear more. Likewise he has myths like the reincarnation story with the Homeric heroes at the end of the Republic for those who have somewhat "missed the point," but might nonetheless benefit from an edifying story.

Making philosophical music requires both reason and imagination. Both arguments and stories, including the stories we tell ourselves. Stories come to us chronologically before reasoned arguments and logically after reasoned argument comes to its end. I will end this with another question: Has the philosopher outgrown the need for stories?

Perhaps, but when it comes to communicating with one another it seems that Plato thinks we will always need images. One can only point to relative goods with words. Images contain something of what they are images of, but they remain images. Nonetheless, such stories can be suggestive of what lies beyond them.

Could more be done with words? Well, two millennia on we have the fruits of centuries of contemplative practice, the Philokalia for example, with its deep phenomenological and psychological studies and significant advice on praxis. But Plato had the inheritance he had to work with. -

A Reversion to Aristotle

I'm not sure how helpful this is if the question is the adequacy of Aristotle's moral philosophy. The Ethics and Politics make it fairly clear what is meant by "happiness." Aristotle himself calls a life spent pursuing mere pleasure "slavish," and a life "for grazing beasts," just a few pages into the Ethics, so the distinction between "flourishing" and something like Huxley's "utopia" in A Brave New World comes into stark relief quite quickly.

To your earlier question re your second example, "vice" has taken on a particular sort of connotation in English were it is either associated particularly with evil or with things like smoking, drinking, prostitution, gambling, etc. Aristotle's use doesn't have this connotation. The virtues are "excellences," and vices are simply the opposite.

So with the person who has overwhelming issues with anxiety, we would say that have a "vice" in the sense that their anxiety keeps them from "living a good life," "acting virtuously," and perhaps even "doing the right thing." A vice is a sort of habit. The idea that vices like cowardice or gluttony could be ameliorated with training á la cognitive behavioral therapy is right in line with Aristotle's philosophy.

Personally, I don't think Aristotle's philosophy is totally adequate. Alsdair MacIntyre advances the "Aristotlean Tradition," as opposed to Aristotle because there are problems extending Aristotle's common good outside the limits of the polis. For my part, I think Aristotle only obliquely gets at why self-determining happiness is superior to mere "good fortune." The connection between happiness and the good (and then the Good and freedom) becomes tenuous in places, in part because Aristotle advances "common sense" arguments based on utility instead of his deeper arguments (which come around in Book X of the Ethics and other places).

Plato does a better job highlighting how the search for knowledge and the pursuit of the Good are what allow a person to transcend what they already are, which means that these serve as the engine of self-determination and freedom. I think later thinkers do a better job refining Aristotle and keeping this thread in Plato from being submerged, but unfortunately these authors have become unpalatable in contemporary secular philosophy due to how their thinking on this is colored by the language of Christian theology.

Hegel is part of this tradition and can offer us a better reason for dismissing the solution of something like Huxley's A Brave New World or even similar, less offensive "utopias" (e.g. human society in Dan Simon's Ilium and Olympos). There is an epistemic element to freedom, best covered in the Phenomenology, that requires the unification of subject and object (Absolute Knowing). Lessss opaquely there is also the demand that the fulfillment of freedom requires that freedom itself becomes the object and content of the (collective) will—"the free will that wills itself."

Anything less is ultimately contingent and arbitrary, and so unstable. -

Is multiculturalism compatible with democracy?

Modern liberal democracy sublated and incorporated into itself core elements of socialism and nationalism. All modern democracies have incorporated core elements of the socialist platform: the right to unionize, universal education, restrictions on child labor, pensions for old age, some form of socialized medicine, progressive taxation, etc.

Nationalism is also universally recognized as key to legitimacy. No one today would claim that Algerians should have been satisfied if the French simply gave them the right to vote and social benefits. Both liberals and conservatives talk in terms of "an Iraqi state for the Iraqi people," etc. The internationalist democracy of the French Revolution is long gone and internationalist socialism is pretty much dead too. National determination is sacrosanct, even as it continues to be problematic in a few cases (Kurdistan, East Turkestan, Palestine, etc.).

So what you have going on in developed countries is that globalization and large scale migration are undermining these two pillars of the modern liberal state. Acceptance of socialism is predicated on the idea that states make up a single organic whole—a people or nation. People are willing to pay in because they see themselves as sort of an extended family of sorts.

In the American case, we can think about World War II and how it serves as sort of the origin mythos for the modern American state. Consider movies about that conflict made from 1945-1990. They almost invariably feature a motley crew of soldiers or mixed ethnicities: Italians, Irish, German-Lutheran, WASPs, etc. And very often a subplot in the story will be about how the group overcomes these divisions and recognizes that they are part of a greater unity.*

Migration on scales where a number of major European states will likely be minority European by the end of this century challenges the "nationalism" pillar of the modern state, which in turn undermines support for the "socialism" part. You might say: "well, even in the US the foreign born population is only about 1 in 7," but this misses a few things. It misses how immigrants are loaded towards the younger rungs of the population pyramid and that they make up a much larger share there, as well as their geographic concentration, particularly in major cities. It misses how second generation immigrants are not always fully assimilated, and there numbers are much higher (e.g. in the US 1 in 4 people are foreign born or have at least one foreign born parent). And it misses how the effects of migration are cumulative (e.g. Pew, hardly an alarmist organization on this issue, has the US at around 25% foreign born and 50+% foreign born or with a foreign born parent by mid-way through the century at current levels).

The age difference is particularly salient. Spending on education and programs for the young is taken as spending "for outsiders." Whereas pensions and benefits for the old are taken as legitimate. This, combined with rich nation's demographics leads to a situation where the next several decades will see investment squeezed out to boost the consumption or the elderly, even as the elderly and the working aged demographic begin to drift apart dramatically in demographic make-up.

The attitudes of new comers is probably less important here than the problems with the current system. People of all sorts assimilated to the American system. The peoples who made up the early Israeli population had little exposure to democracy in Eastern Europe of the Middle East, where most came from. The same is true of South Korea. I'd say the problem comes when there is a lack of assimilation, leading to isolated enclaves that are cut off from the wider culture. The driving issue here is a global inequality in a world that has suddenly become very small. It's not unlike the intracountry wealth disparities that motivated socialism in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Anyhow, this is just one of the problems with modern liberalism. It is also extremely poorly equipped to deal with other "global" problems like climate change, ocean acidification, or the power of transnational corporations. The Post-Westphalian model of the state is insufficient to deal with globalization and the current apparatuses of global governance, e.g. the UN, are incredibly weak. It's hard to see how they will be strengthened without some sort of crisis. -

The Philosophy of Mysticism

A main point is that the focus on "peak experiences," tends to actually exclude a great deal of the people who we think of as "mystics" from the definition because they never wrote about such experiences. For example, the most famous "Beatific Vision" and "Platonic Ascent" in St. Augustine's work takes place in the Book IX of the Confessions. Yet it isn't a meditative trance but rather a conversation with his mother shortly before her death. (Book IX). Likewise, St. Bonaventure's "The Mind's Journey Into God," is cast into the mold of St. Francis' vision of the Seraphim, but that's just the mold for a heavily intellectualized ascent where the prose and ideas, not some actual singular experience, are the focus.

The other big point is that the focus on "peak experiences" to the exclusion of all else has led to a misleading picture because perennialists are searching through disparate texts to find details that fit their notions of what the "true perennial mysticism" is and ignoring how these author's religious context is interwoven with everything they write. Particularly, this sort of abstraction goes wrong when applied to the heavily intellectualized Christian Neoplatonism tradition, but it also shows up in "New Age" versions of Meister Eckhart or Rumi, who have been denuded of all their content, e.g. modern Rumi translations that completely ignore the constant allusions to the Koran in their presentation or "gnostic" or even "Buddhist" versions of Meister Eckhart that essentially ignore both his own claims to orthodoxy and all the evidence for this (or the fact that most of his work is straightforwardly presented as commentaries on Scripture).

The perennialist search for commonalities isn't necessarily misguided, because there are commonalities. However, it becomes misguided when it tries to flatten everything out, and one of the ways it does this is to try to look solely at "ineffable experience," and then to ignore the surrounding religious context as mere "interpretation" of that experience.

For example, if you look at Thomas Merton, who is a deep student of the Zen tradition, he still sees a very deep distinction between it and his own tradition at the level of experience (e.g. the awareness of sin as sin), even though he sees similarities as well. -

The Philosophy of MysticismMy favorite book on this is William Harmless' Mystics. Harmless has a real gift for letting ancient and medieval writers speak in their own voice through careful excerpts while still providing an appropriate background for understanding the passages. He weaves their own words together in a sort of precis. It's a good mix too, Merton, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, Saint Bonneventure, Hildegard, Evargrius Pontus, Meister Eckhart, and then he also covers Rumi and Dogen as a Sufi/Zen comparative study.

He starts off by comparing two views of mysticism, William James' influential modern view and that of Jean Gerson writing in the 14th century. With this comparison he is able to tease out the problem with James' focus on peak experiences, and as many of the case studies show, many "mystics" focus on a great deal aside from there experiences. Gersons' view makes a different sort of comparison. If the theologian comes to know God in the manner of the historian, the mystic's knowledge is more akin to how the someone knows their spouse or friend — a juxtaposition of academic knowledge and experiential knowledge.

Harmless' books on Saint Augustine is also phenomenal, basically all the greatest hits compiled for across his extremely voluminous corpus, as is his book on the Desert Fathers, although that is a bit more historical. -

Reading Przywara's Analogia EntisBeen slow on this but I will get around to parts two and three, which I've already finished.

But I just read a suggestive quote in St. Maximus:

The logoi of all things known by God before their creation are securely fixed in God. They are in him who is the truth of all things. Yet all these things, things present and things to come, have not been brought into being contemporaneously with their being known by God; rather each was created in an appropriate way according to its logos at the proper time according to the wisdom of the maker, and each acquired concrete actual existence in itself. For the maker is always existent Being, but they exist in potentiality before they exist in actuality It is impossible for the infinite to exist on the same level of being as finite things, and no argument will ever be capable of demonstrating that being and what is beyond being are the same, nor that the measured and immeasurable can be put in the same class, nor that the absolute can be ranked with that which exists in relation to other things, nor that that which has nothing predicated of it and that which is constituted by predication belong together. For all created things are defined, in their essence and in their way of developing, by their own logoi and by the logoi of the beings that provide their external context. Through these logoi they find their defining limits.

- Ambiguum 7

'All beings, by the logos by which they were brought to being and exist, are perfectly firm and immovable; by the logos of things seen as related to them, by which the ordering (otKovoµia) of this universe is clearly held together and conducted, all things move and admit of instability.

-Ambiguum 15

From "The Cosmic Mystery of Jesus Christ" translation (selected works).

Note though that subsistent relations would only be said to exist in the Trinity (existence coming from without in every other case).

This relationality is one of the great differences when it comes to created things, even in their universal form. We might say that the sum total of what a finite thing does is expressed in all the ways it interacts with everything else—all the possible "things it can do" in any context. A context, is of course, just being placed in relation to other essences/forms, with existence being determined from outside essence.

Or as John of St. Thomas puts it, "even substance is determined by its relationships to substance," or as Norris Clarke puts it while commenting on Aquinas: "It is through action, and only through action, that real beings manifest or “unveil” their being... [they] actively present themselves to others and vice versa by interacting with each other."

Not only do I think this point is important in the context of Pryzwara's project, but I think the triumph of information theory and the computation-based view of complexity studies across the sciences is a great vindication of this scholastic insight. I really do think modern philosophy made a major wrong turn with its focus on "primary properties" and "things-in-themselves" with Bacon, Locke, etc. and continuing into Kant. So many problems stem from the desire to reduce things down to fundemental building blocks, or to have thing's properties arise from "what they are made of." Even as this view has been undermined in physics, it still seems to remain dominant in the sciences and philosophy writ large.

:rofl: -

A Reversion to Aristotle

Aristotle allows that bad fortune can make people miserable. This is actually an argument in favor of the virtues, and ultimately for the life of contemplation, in that other goods are less stable. One can always experience bad fortune, e.g. the rock star whose next album flops and then realizes they've saved none of their great wealth and are essentially broke. They were dependent on good fortune that was ultimately largely outside their control for their happiness.

Some people might indeed be made quite content through luck or good fortune, but this is of course the least stable sort of happiness since it isn't sustained internally. It's also a state of less freedom since the person is dependent on extrinsic goods. Whereas happiness of the ascetic who is serenely content with much or little is not subject to the same contingency.

Later thinkers like Boethius would however argue that true flourishing essentially comes from knowing and actualizing the Good, and view the happiness that comes from good fortune as a mere counterfeit good. Happiness steming from this sort of self-determining drive towards the Good would be best in part because it seems immune to the vicissitudes of fortune. The further one ascends towards the center from which all things come (the Good, God) the less one is cast about by the whims of Fortune.

This is Aristotle merged with Neoplatonism (and less explicitly, Christianity). Boethius for his part wrote his great work on moral philosophy (the Consolation) while awaiting his execution for cracking down on corruption too hard, having seen a tremendous fall from grace after essentially being the deputy of what remained of the Western Roman Empire. It's actually this text of late antiquity that forms the basis of medieval ethics. Aristotle was largely lost, while Boethius' text was the most copied work outside the Bible for an 800 year span.

By this view the martyr saint seems to be the paradigmatic case of happiness precisely because of their absolute freedom (at least at the over of their own persons) to embrace the Good. -

A Reversion to Aristotle

What does Aristotle say about this? Is there a term, or an ethical condition, that can describe a person who has "fallen into vice" but not only doesn't know it, but is convinced that they desire the exact opposite?

This would be the state of vice—which involves the enjoyment and pursuit vice and ignorance vis-á-vis true virtue.

Incontinence is the state where a person can properly distinguish virtue from vice but still acts according to vice due to weakness of will.

Continence is knowing virtue as virtue and acting according to it, but still desiring vice.

Perfected virtue entails that one acts virtuously and enjoys/prefers virtue to vice (e.g. Socrates prefers to drink hemlock as opposed to acting against virtue in the Crito).

So you can see an immediate contrast here with Kant, who would have it that we are in a way being most good when we "do the right thing," despite having no desire to do so.

Virtue is key to true self-determining freedom. Obviously, we are not born with this freedom. Education and training in the virtues is thus essential, and Aristotle at times likens the way we learn to practice the virtues to how we learn and perfect trades/skills (techne).

Part of the incoherence in the modern tradition that Nietzsche picks up on is the way in which acting morally can seem like a burden that makes life less worth living. It is "life denying." Yet he backwards projects this onto Plato and the classical tradition. Plato by contrast has reason reaching down into and coloring the desires, and speaks of ecstatic eros for the Good, or even "coupling" with it. Likewise in St. Aquinas we have the intellect coloring all of the lower faculties given the proper orientation. Asceticism then isn't about denying the desires tout court, but rather training them in order to fulfill them more fully (freedom as giving birth in beauty). The charioteer of reason in the Phaedrus trains the two horses (appetites/passions), he doesn't kill them or pen them in a stable, but ideally has them running at full gallop as he takes off towards the sun in an act of self-generating reflexive freedom (this of course doesn't obviate Nietzsche's critique more generally, it's just that it seems a bit off the mark when ascribed to the classical tradition). Kierkegaard is often grouped with Nietzsche despite having an entirely opposite view of Christianity in part because of this same sort of insight. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

The explanatory gap is a problem for contemporary science and the way it has defined what a proper explanations must look like. I do not think it's a particularly important thing to solve in order to buy into (or reject) Hegel's philosophy of history, politics, concept development, etc. Ultimately, his project is to wrap the subjective and objective in a third category that includes both, since both must be real in some important respect. This project is accomplished (or fails) upstream of considerations of some objective explanation of the emergence of Giest in Nature, at least at the level of scientific modeling.

Hegel certainly has something to say about mechanistic accounts along the lines of Newton's, which only result in predictive models and cannot explain their own necessity— so in some ways he is offering a critique of some types of scientific explanation that could be relevant to the "explanatory gap." I think changes in the philosophy of physics have perhaps made Hegel's critique a bit less relevant, although it certainly holds for some sorts of explanation.

Count Timothy von Icarus

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum