Comments

-

Is emotionalism a good philosophy for someone to base their life on ?

In his "History of Theology," lectures for the Great Courses, the philosopher Phil Cary points out that today, in the shadow of the Holocaust, we tend to worry about "becoming machines." Whereas in ancient philosophy, the top concern was more than we would "degenerate into beasts."

Looking at myself, the people I know, and the world around us, I think we flatter ourselves in worrying about becoming "too rational." I think the ancients had it (more) right — that the biggest threat to our personal sovereignty is generally that we become slaves to our own disordered drives, desires, and instincts.

That said, I've always tended towards the romantic side. I don't think it has to be an either or. Rationality and self-discipline/self-government need not mean a sterile and robotic life. Rather, when we are most in control of ourselves, we are most able to love and help others. Our love is more ours in this case, less an effect of external causes.

Plato, Augustine, and Hegel are both very much "be ruled by reason," types, but then they also write more about love and the family than other major philosophers I can think of. -

Free Will

So, what determines the "free part" of the decision making process?

If it's nothing, then it's random.

If it's us, then it seems like our choices are based on the type of people we are, which is in turn shaped by past events and our nature. In which case our choices "follow from" us. And since we preexist our choices, it would seem to be the case that we also exist in states that are antecedent to our choices.

If it's a "free will" that exists without reference to our past experiences, preferences, and nature, how does that work? I don't see how our choices can be both "determined by," but "not really determined" by the self that exists prior to a choice being made. But even more so, if seems that, for me to be free, my decisions have to be based on my knowledge, preferences, feelings, past experiences, desires, rational thinking, etc. These pre-exist any "choosing," and to the extent that my choices are based on a free floating free will instead of on these pre-existing factors, I would say I am not free. Some will that has nothing to do with what makes me who I am is then chosing.

This is of course leaving aside the problem of how our choices could ever reflect our will if our actions lack determinate effects. We can only make choices that bring about the states of affairs that we prefer because we know what the effects of our actions will be (which goes back to past experience).

It would seem to me that most philosophers take the "free" to simply means "possessing freedom." They all define freedom differently. Saying "free" means "free from determinism," is just begging the question on libertarianism versus compatibilism. -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?

But that was exactly the response to people first positing that the Earth is spinning: "it doesn't seem like it's spinning."

It doesn't appear that way to your senses, but it is, right? Sure, we can explain why this is the case. The same is true for the bent stick and the optical illusion I posted.

Plato's point isn't that we are tricked by the stick in the water. It's that we can be tricked, and so our naive judgements aren't always going to lead us to the correct conclusions.

Maybe so. Hume was responding to the thinking of his day though, so it wasn't really a contrived or affected consideration. -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia

Quite so. That's the essence of what the "analytic" philosophers believed, and explains why they spent their time talking about language.

Well that and trying to turn language into sense data by claiming that: "the meaning of a sentence is the empirical data that would verify (or falsify it)." This view is runs into a host of problems, not least of all that it is a statement that it does not seem possible to verify based on sense data.

Does Sebastian Rödl consider the possibility that I might walk round the apple and discover that there is an apple?

Yes, that's sort of the point. You can see the whole apple by moving around it, but you cannot see it all at once. Now what grounds do you have for saying: "before I could see the back side of the apple, now I can see the front. Since this remains the same individual apple I looked at earlier, I am justified in positing that I am looking at a whole apple that has a back that I cannot see?"

Common sense tells us that we can justify this with recourse to the idea of the apple being an "object" that can be seen from many different directions. But common sense isn't "sense data." Common sense includes "metaphysical" concepts like "objects." Any solution also seems to require a consideration of time and temporal logic, which is part of Rödl's argument. But also consider that any apparent apple could just be a crafty hologram as well.

Rödl's point might seem fairly silly from a common sense point of view, but he rebutting fairly technical attempts to show how knowledge could possibly be reduced to merely sense data. These attempts also had to "leave common sense behind," like most philosophy, since it turns out a lot of unchallenged assumptions are packed into common sense.

The problems for a sort of "arch-empiricism," only gets worse if you assume that any reference to metaphysical terms like "object" means only the very sense data that might verify the truth of a statement involving them. I tend to lean very empiricist, but I think the positivists just took this in a bad direction.

Plus, it seems to me that mathematicians talk about infinities and continuums all the time, and theologians and atheists debate about God all the time, while having meaningful discussions, despite the fact that anything infinite or infinitesimal cannot be verified through sense data. -

Free Will

So what we know doesn't determine our actions at all? Then why does everyone choose to get up when the fire alarm goes off?

If information didn't determine our choices, this would seem to be a serious limit on freedom. I would like to think that I love who I love and despise who I despise because of who they are, what I know about them, etc. That is, past experiences would help determine my actions relative to people.

But if information has no interaction with choice, then what determines our actions? It can't be our opinions, because those are formed by our past experiences and information about the world. It can't be our preferences unless said preferences are free floating, and not grounded in past experiences or our information about the world. This would seem to simply make our actions arbitrary, random — this doesn't seem like freedom.

So to answer your question: no, freedom is about what we choose to do not about metaphysical possibilities.

I don't think a libertarian free will where a "choosing entity" sits free floating outside of all our other experiences is coherent. If I freely decided to turn the AC up because I feel hot, my "feeling hot" determined my actions. If there wasn't this sort of interaction between the rest of my self and my will, my choices could only be random and arbitrary, determined by nothing, and thus I could not be "self-determining," in any sense. -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia

There are at least three aspects to this problem - it's really a series of problems. First is the problem overtly addressed in the present essay: how is it that we can move from the evidence of our senses, on which empiricism is supposedly grounded, to making true statements about the world? Second is the problem of induction, how we can move from a series of such observations to a general principle, a "law". The third problem is to do with when we might correctly say that one even causes another.

A rather famous quote on this problem:

When I say “This is an apple” and only see the front of the apple, then what I say goes beyond what I see. It includes the back, which I do not see. Therefore it is possible that I walk around the ostensible apple and discover that there is no apple. Now, no sum of perceptions can exclude that later perceptions will show that despite appearances there is no apple. Like a general judgment, the judgment “There is an apple” goes beyond everything that we will ever have perceived. . . . If what is sensibly given in itself falls under the category of substance . . . then empirical knowledge always already contains general knowledge, which therefore is not inferred inductively from the former.

-Categories of the Temporal: An Inquiry into the Forms of the Finite Intellect - Sebastian Rödl

For a long while Popper's falsification was the winner

The biggest knock against Popper's theory I can think of is that it has been invoked so many times to call areas of scientific development that later yielded huge breakthroughs "unfalsifiable pseudoscience." Mach, writing before Popper, famously thought atoms were pseudo-science. Popper was invoked to deny quarks a hearing in physics. We see the same sort of attack leveled at quantum foundations to this day, even though research there does indeed progress and touch other areas of the field.

It seems to me that:

A. Scientific theoreticians cannot avoid doing metaphysics.

B. The anti-metaphysical, empiricist-positivist view dominant until fairly recently does get rid of metaphysics, it just enshrines a certain type of metaphysics dogmatically. After all, saying it is "meaningless" to even talk of certain things is, in an important way, to make a metaphysical claim about them.

(For my part, that this discussion should take place at all shows something of the poverty of the sense data theory)

It's also a strong form of reductionism in a way, even though it is often advanced by people who have nothing good to say about "reductionism" in general. It says that experience cannot be fundamentally about the whole of a relationship between some object of experience and some experiencing subject. Rather, the only way to understand the phenomena is by reducing it to phenomena "within the subject."

This seems to cut against a lot of the theorizing in embodied cognition, which I tend to find fairly convincing, while also tending to suggest a view of "sense datum as discrete things," instead of the more plausible view (IMHO) of "sensation as continuous process."

Part of this, IMO, is that Kantian dualism often ends up "baked in" to theories in cognitive science from the get-go. That is, the reduction of experience to a process that only involves the discrete object of study (generally the brain) all but ensures that the same problems that show up in Kant will show up here, because they are presumed from the outset.

A larger issue is that we've generally dumped potentiality, essence, substance, natures, and even form (to a lesser extent) from natural philosophy because they are unobservable. But then we work them back in via less obvious forms because we need them. E.g., thermodynamic entropy, information entropy, the heat carrying capacities of metals, etc. all involve a sort of "potentiality." So, metaphysics still lurks around, it just is less well examined. -

Free Will

Seems to be the case to me. When a fire alarm goes off, everyone stands up and exits the room. The alarm seems to play an important causal role there. When you see smoke billowing from your kitchen, you go and grab the fire extinguisher. Incoming information affects behavior.

Of course, it isn't the only thing involved. Past experiences with fire drills also play a causal role in people's behavior. Ears and brains are involved, etc.

I would put it like this: given the way the world is, the fact that people experience fire drills routinely, the fact that loud piercing sirens and flashing lights get our attention, etc. the fire alarm sits astride a "leverage point" as a subsystem that is part of the overall system of "the building and all its occupants." By doing something very simple, it can cause a huge change in behavior. This is a trait of complex systems: a small change in one place can cascade into major global changes across the system.

But when we talk about "freedom," things get more complex. Why is the fire alarm there? Because someone engineered it for a certain purpose -- to warn us about fires. If we put an alarm up in our house, then it is basically acting as an extension of our will. So even though it plays a causal role in our behavior, it doesn't necessarily constrain our freedom. It's the same as when we leave a post-it note for ourselves and it reminds us to do something. The note has causal efficacy, but it has the effect we will it to have.

Manipulation and brainwashing are different. In this case, the information guiding us is largely an extension of another person's will. We aren't acting completely freely if we wouldn't commit to the same acts if we weren't being manipulated.

Modifying Lynn Rudder Baker's definition, I would say an act is free when:

- We want to do x and we actually do x.

- We want to want to do x. (i.e., Frankfurt's second order volitions)

- We do x because we want to do it (it is not a coincidence, our wanting is causally involved in the process)

- We would still want to do x even if we understood the full provenance of why we want to will x (i.e., there is not some fact we might discover that would make us no longer want to do x)

These conditions, particularly the last, are difficult to meet entirely. This is no issue, an act can bemore or less free; freedom is not bivalent. Manipulation seems to make us less free by acting on the last point.

Another thing to note here is that, under the above definition, knowledge and information help us to become more free. This makes intuitive sense. Know-how enhances our causal powers; technology lets us do things we otherwise could not. Knowledge of the world affects our decision-making. The more we know, the more we can be guided by unifying reason, instead of by instinct, desire, and circumstance. Knowledge of the "why" behind our actions is especially important. Without such recursive self-knowledge, we are always motivated by what R. Scott Baker calls "the darkness that comes before," things we cannot fathom. This turns us into a mere effect of other causes. -

A Holy Grail Philosophy Starter Pack?

In my experience, historical surveys have only limited value. They are good for understanding intellectual history, less so for understanding philosophy. The problem is that you might get one dose of philosophy of mind on page 120, then not see the area again for 100 pages. To be comprehensive, surveys must be quite shallow, and they normally describe thinkers in terms of their historical relevance instead of how they tie in to contemporary problems.

Kenney's "A New History of Western Philosophy," is my favorite survey because it includes topical coverage, but it still suffers from the same shortfalls. Durant has great prose and I love "The Story of Civilization," as a history, but his "Story of Philosophy," leaves a lot to be desired.

I found it much more fruitful to dig into specific area surveys and then go from there.

Not knowing what will interest you, I will just throw out my favorite (more) accessible works (some topics are less accessible by nature). My personal advice: read or listen to "Complexity: a Guided Tour," and "The Ascent of Information," if you're at all into metaphysics and science -- i.e., "what the world is like." They cover the most fascinating areas of the sciences IMO and give a very different view of the world than the classical "balls of stuff bouncing around."

Three resources are worth mentioning in general:

- The "Oxford Very Short Introductions to..." series. They get quite good people to write these and they cover a host of topics that it is quite hard to find introductions on. They are 80-120 pages, short.

The one on Objectivity is excellent, and it covers an area where thinking is often very confused. The one on Mathematics is also quite good, as are the ones on Continental Philosophy and Analytic Philosophy. Unfortunately, despite Floridi being an author I really like, I found the one on Information fairly lacking. These are the only short introductions to the philosophy of physics and the philosophy of biology I am aware of (both are good).

- The Routledge Contemporary Introductions to... covers most core areas in philosophy, giving you a good lay of the land and coverage of dominant theories and problems. I can speak to the metaphysics one (quite good), the one on Free Will (good), and one on Time (good but there are better resources), the Philosophy of Language one (good), and the one on Phenomenology (also pretty good). Jarwoski's "Philosophy of Mind," and "Problems of Knowledge" (epistemology) are better intros than the Routledge ones for those areas though.

Oxford has a similar series called "X: The Basics." I've only read the semiotics one, but that is quite good. Eco's "Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language," while less introductory, is more interesting though.

The Great Courses does lectures on a wide array of topics. It's like sitting through a college course, and they tend to get award winning lecturers. Don't buy them direct, as they are horribly expensive. Audible lets you get many free for a $15 a month subscription (and you get a book per month with that). Wonderium gives you all the videos and you get two years of access for like $40 if you do a trial and then cancel. Only problem is it does not have audio files so it drains your phone battery quicker if you just listen in the car or while doing chores.

These have more science content, which is good to pair with the philosophy content. So the one on the neuroscience of language would go well with the Routledge guide on philosophy of language (which is very light on science). Of these, the "Mind Body Philosophy," one is excellent, as is "The Science of Information," and "The Philosophy of Science." The classes on Complexity and Chaos Theory are good too. "Descartes to Derrida," is a quite good survey of modern philosophy, as far as surveys go. The free will one and the "search for value" is also good. The only one I really thought was lacking was the one on metaphysics.

Then, for general reference, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is quite good, if sometimes too technical. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy is also peer reviewed, and tends to be less technical but has less specialized content.

Springer Frontiers tends to have a lot of really good cutting-edge philosophy of the sciences stuff. "The Reality of Becoming: Time Flow in Modern Physics," is my favorite on philosophy of time. "Asymmetry: The Foundations of Information," also has the best intro on information theory and entropy I have found, even if the proof parts at the end are quite technical. "Particle Metaphysics," is a good one too.

For mysticism, I particularly like Harmless "Mystics." His "Saint Augustine in His Own Words," is the best survey of Augustine as well.

For free will and ethics, I like Wallace's "Philosophical Mysticism in Plato and Hegel." It's a great intro to a powerful but often misunderstood tradition in these topics. The title is misleading, it's more a conventional ethics/free will text than about mysticism.

For an intro to the philosophy of history, M.C. Lemon's intro is my favorite. Routledge and Oxford don't do this topic.

For Hegel, Pinkhartd's "Hegel's Naturalism," is a short, accessible account of Hegel, if a bit "deflationary." Dorrien's "Kantian Reason and Hegelian Spirit," while focused on theology later in the book, is the best intro on German idealism I have found. Houlgate's commentary on the Greater Logic and Harris' "Hegel's Ladder" for the Phenomenology are both great. Bernstientapes.com has full graduate seminars recorded on Kant and the Phenomenology as well (free).

For complexity and information theory, "Complexity a Guided Tour" is a fantastic introduction to all sorts of interesting stuff in the sciences related to information theory, chaos, and complexity. The North Holland Handbook of the Philosophy of Science volume on complexity is great too, but impossible to even find outside LibGen and fairly technical. "The Ascent of Information" is also a really interesting book on these topics that has big ideas while being accessible.

For quantum mechanics, "What is Real?" is a very nice intro. Tegmark's "Our Mathematical Universe," is fun too, as is Vedral's "Decoding the Universe" (an information theory-centric account). "Information and the Nature of Reality" is a neat one too, but more general physics and includes articles by biologists on information theory.

For Logic, "For All X" is open source and what is used by a great deal of programs now. Routledge has intros for more advanced logic. These are a slog if you aren't in a class though. "Meaning and Argument" is apparently an intro to logic that pulls in content from the philosophy of language; that might be more interesting.

For computability there is:

The Routledge Handbook of the Philosophy of Information: for after the Great Courses course or the Ascent of Information. It's more technical, but filled with interesting articles.

Bernhardt - Logic and computability: Turing's Vision: The Birth of Computer Science - solid intro to Turing Machines and the mathematical problems that defined the early 20th century.

Hofstadter - Gödel, Escher, Bach (if you really care about formal systems, otherwise Complexity: A Guided Tour is better)

Math - More Precisely: The Math You Need to Do Philosophy. Solid introduction to sets, machines, probability, and information theory. Still dull, more something you read to understand other things lol.

Then, for any particular area you want to go deep in, look for the Routledge, Blackwell, and Oxford "handbooks to." Again, Libgen might be a go to here because these are atrociously overpriced. These give you good, curated articles on specific topics (e.g. emergence, biology, etc.) Princeton does the best philosophy of physics series though. -

Free Will

I'm not sure how this is the case. If I am manipulated, brainwashed by propaganda say, then it seems my actions can absolutely be determined by that.

Like, if you're sent to some alien planet to destroy the Goobleblogs and you've been told that this species' one goal is to eradicate all other life in the galaxy. You think you're involved in self defense against an implacable foe, and so you act accordingly.

As it turns out, the Galaxy Defense Force intentionality mislead you because they want all the unobtainium on the Goobleblogs land and they are actually a friendly, peace loving people.

Then it seems like the manipulation plays a key causal role in your actions. -

What are the best refutations of the idea that moral facts can’t exist because it's immeasurable?

Morals can't be universal since they're essentially tied to the being of humans.

How does this work? We can have a universal definition of "life" right? But life is tied to the being of living organisms. Or a universal definition of parasitism, yet that too is tied to the existence of organisms.

Is the problem that "good and bad" are part of first person experience? Or is it that they are only relative to living things?

But an indifferent, meaningless existence in a deterministic universe creates problems for any objective morals to be found, because they cannot be found.

Sure, but likewise, if universal morals can be found, then the universe isn't meaningless. Which one are we in?

I'm not sure what determinism has to do with it. It seems to me that, for a universe to embody meaning and values, it must be determined to do so in some ways. Else how is the meaning in the universe instantiated except by chance? But I can't think of any reason why determinism should preclude universal values. We can imagine a mad scientist who spawns a toy universe that starts off chaotic yet which has a universal tendencies that will cause it to spawn life and then maximize the well being of those life forms. That would seem to be a case of values being instantiated through determinism. -

What are the best refutations of the idea that moral facts can’t exist because it's immeasurable?

Lots of things in the sciences lack a tangible "body" and contain subjective elements. However, we still think we can meaningfully measure them.

For example, most people would agree that "economic recessions," exist, and that they have real causal effects (e.g. construction projects coming to a halt across the world). However, our measurements of GDP growth, real wages, CPI (inflation) etc. are all highly operationalized, contrivances for approximating a measure of a real phenomena.

Even measurements in the physical sciences have a similar "squishyness." Jaynes argued that entropy has an essentially subjective element, and I think he is right here. We have multiple different measures of "complexity," and virtually no one thinks they are perfect . Yet there is widespread agreement that "complexity" does indeed exist as a property of physical systems. Likewise, we might debate how well current IQ tests measure intelligence, but it seems pretty clear that intelligence exists and that some animals have more of it than others.

The existence of incorporeal things isn't the problem then, IMO. People will admit that something like "Japanese culture," really exists in the world, and that such an entity includes moral elements. People will generally also allow that there are facts about what individuals think is good or bad. E.g., "Tom thinks adultery is wrong," is a fact.

Further, they will even allow that, in the aggregate, we can make factual statements about what given cultures tend to think is good or bad. E.g., it is a fact that "most Americans Evangelicals think that abortion is morally bad." Likewise, we can make factual claims about what is "good or bad" given some sort of code (e.g. per the "chivalric code," cowardice is bad — this is a fact). Such fact claims hold up even if no one actually buys into said code.

Where people seem to deny the existence of facts vis-á-vis morality is when claims are made about a global moral code.

Here I see two common objections, one serious and one that is trivial.

The trivial objection is that: "your morality depends on where you grew up," and "all cultures have different morals." This is trivial because the same was previously true about how people thought infectious diseases worked, if the Earth revolved around the Sun or vice versa, etc. Yet we do think there are "facts of the matter," about how disease spreads, even if every culture did have different views earlier. Plurality of opinion does not suggest that knowledge is impossible by any means.

The more potent objection is that it seems quite difficult to know where to start in measuring "goodness." Economists come the closest to this sort of thing in their measurements of "utility," but that isn't really the same concept and we have reasons to be dubious about our ability to measure it anyhow. At the same time though, our inability to operationalize things in no way means they do not exist, else we'd have to throw out complexity, life, intelligence, etc. on the same grounds.

"Harm" can be grounded in biological terms at least as well as "life," so that's a start. There are also "facts of the matter," about whether someone finds something pleasurable or painful, and while we can't read minds, there are decent ways to figure these sorts of things out for human beings and animals. Thus, an objective morality grounded promoting pleasure and minimizing pain, or in minimizing harm seems possible.

The problem here is that we might also consider "aesthetic good" important, or freedom as a good in itself. Hegel elevates freedom to the highest good, in part because free, self-determining individuals who are freely, willingly part of a free, self-determining society, will chose to maximize their pleasure and minimize harm to the extent they are able to. A person doesn't choose to be miserable if they can be happy. And they will choose what they think is best aesthetically. In this way, the "promotion of freedom" comes up as a good candidate for "objective morality." -

The American Gun Control Debate

That's a fair point. The consideration for an individual is different than that of the policymaker.

Slightly related point: freezing the sale of new automatic weapons did seem to have the effect of getting them all into the hands of people who are highly unlikely to use them in homicides it seems. America still has a lot of automatic weapons floating out there, but now they are quite rare and expensive. It takes a lot of work to own one and now they are rarely ever used in crimes. I do think this is related to the high cost and their status as collectors items instead of "weapons." -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?

Plato uses the "stick in water" example because it's an obvious example of sight not matching reality.

A and B being identical shades of gray would be a less obvious example. I've had students refuse to believe they are the same before I copy and paste them into the same paint file before, so it definitely isn't intuitive.

I think those like Austin show that in most cases, if not in all of them, the "naive view" starts to "become insurmountable" only due to confusion and error

IDK, wouldn't the Earth being round, the Earth rotating around the Sun, etc. all be examples here? Same with Galileo's finding re the period of pendulums and the rate at which things fall in a vacuum. Aristotle"s physics remained so popular for so long precisely because it was intuitive and seemed to match sense data. -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?

Which I think some (like me, maybe) would maintain constitutes a confession he himself

disregards the claims he makes in philosophy all the time. One would think that should make a difference to him, and to others, in assessing the validity and value of his claims.

There is an important bit of nuance here; Hume absolutely did think that we couldn't justify induction without reference to induction. He does appear to take this claim seriously.

If Hume is right, then we can't justify induction via any straightforward, foundationalist, rationalist argument.

This isn't inconsistent with Hume saying that "of course we still end up using inductive reasoning, because we sort of have to."

Likewise, his reduction of cause to constant conjunction has a similar bit of nuance. Does he really think cause doesn't exist? IDK. Does he take the epistemic issues his argument highlights seriously? Absolutely. -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?

The closest real example to the sort of thing you're talking about that comes to mind is Parmenides' denial of the reality of change. However, it seems like his whole point was to show the flaws in the "common sense," view, rather than to put forth an equally common sense/naive view of changelessness.

As you say, such things are normally put forth as thought experiments. What they generally try to show is that the common sense explanation of things cannot be the case, not that the "silly" view is the case. This isn't always true, but it often is. I think that when people embrace extremely counter intuitive ideas of the world, it is because the problems with the "naive view" start to seem worse. That, and some people enjoy being iconoclasts and going against the grain.

I don't think this is (always) affectation meaningless naval gazing though. People have been writing about philosophy for about as long as they have had written language. It's natural to us. Thinking through these sorts of things is natural. A lot of our world is quite counter intuitive, which gives us grounds for testing bedrock assumptions.

Think about a question as simple as "what does it mean for two things to touch?" This actually has a very complex and counter intuitive answer in physics. We don't need to know this answer to know what is meant by "touch" in everyday speech, but knowing more about the more complex answer has helped us do things like build cars, cell phones, GPS satalites, etc. In that way, questioning our starting point is worthwhile.

Likewise, animism is sort of the human default. Both human children and early societies tend towards animism. "Why does the river flood?" Because it wants to. "Why does it rain?" Because the sky is mad.

We have no problem figuring out what someone means by "an angry sky," or what people are saying when they say "free hydrogen atoms want to pair up with oxygen atoms." But at the same time, questioning our initial animist, common sense proclivities, turns out to be time well spent.

My guess is that, if we ever get a really satisfying answer for the relationship between particulars and universals, or a satisfying explanation of how parts relate to wholes, these will actually come with some pretty significant advances in technology and scientific understanding. They seem so basic as to be irrelevant, but the same is true vis-á-vis what it means for two objects to "touch." -

The American Gun Control Debate

Sure. But firearms also make committing murder much easier, so you also will get homicides that wouldn't have occured without the guns.

You get two offsetting effects. There is a deterrence and self defense effect, but also the effect of allowing people to commit murder much easier.

On the whole, the ability to kill people easier (and to accidently kill bystanders while carrying out an attack) seems to outweigh the deterrence and self-defense effect. There is plenty of evidence to support the contention that, all else equal "fewer guns = fewer murders."

And that seems to me like a pretty good argument for gun control. Moreover, the types of restrictions you put on fire arms can also shift the degree to which guns are used for self-defense versus homicides. Fairly banal firearms regulations still do plenty to keep guns out of the hands of the most unstable citizens. -

Does Religion Perpetuate and Promote a Regressive Worldview?

Like many atheists, I generally call myself an agnostic atheist

Gotcha, I see what you're saying now. That makes sense to me.

I'm not arguing form desire, I'm arguing for preference. Possibly aesthetic preference. For some people the world makes more sense and is more beautiful if they have magic man in it. For others, there is no need for this.

I certainly think you're on to something here. There is a sense in which "the type of person someone is," can lead them towards or away from any given religion. I think the same is true of political and philosophical leanings as well. Even among people with fairly liberal policy preferences, I think it's meaningful to talk about "conservative personalities," to some extent, etc.

However, I also don't think it completely reduces to these sorts of preferences. Your classic, more shocking conversion stories (in either direction) tend to be more based on evidence for some sort of position change (be that mystical/direct experiences, or the fruit of intellectual investigations).

To embrace the bolded explanation would seem to require discounting such narratives in place of a sort of psychoanalytical explanation about what is really going on. Aside from not being a fan of such explanations, it also seems sort of condescending. It's the atheistic equivalent of the theists' explanation that: "people who don't believe in God do so because they are unable overcome their own ego's demand that they be in control and the standard of their own goodness."

Now might either of those have some merit in some cases, sure. But it seems rather hand wavy given that all different sorts of people are atheists or religious. And of course, in both explanations its "the other side" who has some sort of intrinsic quality that leads them into their belief, which seems too simple. -

Does Religion Perpetuate and Promote a Regressive Worldview?

As I said, I'm not saying it's an exact match. I would not agree with medical treatments to cure religion either. But on the other hand, many people do start heterosexual, marry and have children with a partner, only to realize after a few years that they were following this conventional path because of expectations and socialization. On encountering the world, on further learning, they might 'come out' and change preferences. People's experiences with religion can be similar. They were never really comfortable with it, but had not yet encountered alternatives or learned that it was ok not to believe. Taboos against atheism and homosexuality have been powerful and still are in some countries. Education about both is important

Sure. But this is true of embracing liberal/conservative policy positions in many enviornments as well. It's also true re idealism vs physicalism.

My point would be that the phenomenon of shifting religious beliefs shares much more in common with the phenomenon of shifts in other beliefs than in changes in sexual orientation, tastes for certain types of food, etc.

Beliefs are in some ways quite distinct from desires. Religion is about both belief and identity, so there is cross over, but the closer analogy IMO would be becoming a liberal/conservative later in life, or changing one's mind on some core philosophical issue. -

Does Religion Perpetuate and Promote a Regressive Worldview?

A philosophical 'doctrine' coopted by early Church theologians but "Neoplatonism" was not itself ever a creedal or congregational religion, or religious practice. Doesn't meet my state criteria (re: Pascal's distinction of the religious 'God of Abraham', not a conceptual 'god of philosophy')

I agree that it lacked some common elements of organized religion. It did have a practical side focused on "inwards and upwards meditation/contemplation" that seems more religious though.

In any event, the direction of influence between Neoplatonism and orthodox Christianity, Gnosticism, and Jewish Platonists is probably one of the most common "large," mistakes I've seen in philosophical histories. This certainly stems from the fact that later Christians and Jews assumed that "Pagan = older," and tended to write the intellectual history that way.

In reality though, a young Plotinus is growing up at a time where Origen and Cyril are his city's most eminent Platonists and where conflict between orthodox Christians and their Gnostic brothers was at a fever pitch. Key "Neoplatonic" elements of Gnosticism show up first, then in Neoplatonism only later. The Platonist tradition in Alexandria's Abrahamic community goes back centuries earlier, back past Philo and co.

So, while we don't have all the intellectual history we'd like, it's more plausible that Neoplatonism is a sort of continued abstraction and re-paganization of Jewish, Christian, and Gnostic ideas.

Of course, the influence would later go both ways. Saint Augustine, the West's most influential theologian, would read the "Platonists" first (likely Porphyry and Proclus). And because Augustine does so much to try to make Neoplatonism consistent with orthodox Christianity, it was generally taken that this must be the primary direction of influence. But his success makes more sense when you consider where Plotinius was getting his ideas from.

I'd have to consider it more, but I don't think that sort of definition works for atheism in most forms. To be sure, one can lack belief in something without having a corollary belief that the thing in question does not exist. E.g., many people have never heard of a lepton. They don't believe leptons exist, but they also don't believe that they don't exist.

But is this the type of "lack of belief" that atheists are generally talking about? I would think not, because normally, they have heard about God and considered the evidence for God. Dawkins, for example, thinks there is strong evidence to think the teachings of traditional religions are false.

Now you can also lack a belief in something that you know "something" about and still not deny its existence. However, this seems to me to be the "agnostic" view point. E.g., you can read a book on string theory and remain unconvinced by it, lacking belief in the truth of the theory, but also lacking any strong belief that it is false.

Is this the sort of lack of belief the term "atheist" generally applies to? I don't think so. Think about one of the core policy demands of atheist groups: that students in public schools not be taught the positive claims of religions in class. Such a demand makes sense if you think said teachings are false or unlikely to be true. The demand makes no sense if you have no belief vis-á-vis the teachings being false.

If I have never been exposed to modern chemistry, I might very well "lack belief in," many of its theories. But my lack of belief in these theories gives me no good reason to demand that such theories not be taught, right? Indeed, if we demanded that things we didn't currently believe in not be taught at schools, we would essentially be setting our current beliefs as the limit for all education. It would be akin to demanding that subjects you had never studied not be taught.

The common atheist position is far more reasonable than this. The claim is generally that the teachings of religions are unlikely to be true (i.e., that they are likely false). And it makes perfect sense to advocate that things that are likely to be false are not taught to students.

The common agnostic position makes more sense too. It is that it is impossible to determine the truth or falsity of key religious beliefs, in which case it wouldn't make any sense to teach them as if they were true. Or we could say that, if side Y wants to teach X, we can allow that Y does not have good evidence to support X, and thus that we shouldn't teach it, without having to suppose that X is false. But this is generally the position labeled "agnostic," which the above definition folds into the lable "atheist."

But simple lack of positive belief is not a good reason to advocate against a position being taught.

Atheism is not a religion, but it's still a belief. -

Does Religion Perpetuate and Promote a Regressive Worldview?

"Thou Shalt Not Believe Hearsay"?

or, better yet,

"Thou Shalt Believe In Only That Which Can Be Shown To Be The Case'?

Neoplatonism?

Saint Aquinas has the model of the "two winged bird," faith and reason. The above holds for "that which is known through reason." This certainly doesn't support the whole of the Christian religion, and some of Aquinas' rationalist arguments are open to solid criticisms, but he gets a considerable amount of milage out of demonstrable deduction. This is also of true of Thomas's precursors, Maimonides, Avicenna, and Avarroese. Averroes in particular sets logical reasoning above revelation, having the latter interpreted in light of the former where contradiction is discovered.

We might say similar things about Aristotle's God, although that never got the widespread appeal that Thomism got. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Agreed.

2. Western support. It may be perceived that Israel is doing all their nastiness with support and resources from Western countries, in ways that the other countries are not. The average American may think (whether right or wrong), my country is more involved in this conflict, which means my voice matters more than it would in some conflict my country is a lot less involved in

This ties into (selective) awareness. Support for Israel is top of mind in part due to the powerful Arab reactions against it (e.g., the oil embargo, 9/11 was carried out ostensibly for this reason, etc.).

Egypt is also a huge beneficiary of US aid, as is Jordan and Iraq. The Gulf States pay for their hardware from the US, EU, and UK with their oil wealth, but as customers they are far larger than Israel. The Saudi defense budget alone is more than three times the size of Israel's, and they operate comprably far more European hardware (Typhoons, Tornados, Rafales, and Grippens). They're getting more US hardware as well and were recently involved in a long war that killed over a quarter million people. Not only this, but US intelligence was actively assisting their efforts and US assets were actively hitting targets in Yemen, flying recon, etc., a level of support Israel has not received in any of its wars.

This is not generally reflected in public understanding, and I think that ties back into the other factors we've both mentioned. -

Free Will

I wonder if a fundamental cause of the controversies is that the concept of free will is poorly defined.

Absolutely. It's an even larger issue in theology.

I would just add that another element of the problem is the fact that people conflate determinism with "smallism," the idea that facts about larger wholes must be reducible to facts about small constituent parts. Then, because we generally assume that atoms and molecules lack intentionality, this then suggests that determinism requires that minds, beliefs, etc. can have no causal efficacy. After all, if all thoughts, beliefs, perceptions can be reduced to facts about mindless molecules, then such things must be in some way "illusory" vis-á-vis any causal explanation of phenomena.

But I don't think this is at all a consensus, or even a common opinion in philosophy. To be sure, reductionism and smallism are popular, but the concept that they are essential to elements of determinism is not. Rather, people seem more likely to embrace determinism because of smallism.

Part of this seems to stem from problems with viewing "natural laws," as extrinsic, Platonic forces that exist "outside" the universe, but act upon it. This is sort of the Newton conception of the "natural laws." This has been replaced to a large degree by Kirpke's essentialism, the idea that "laws" simply "describe" regularities that exist because of properties intrinsic to objects. E.g., water acts the way it does because of what water is.

Essentialism doesn't require smallism. We could as well say the world acts the way it does because of what universal fields are. However, it was originally framed in smallist terms, and so the two have become contingently wedded.

I buy essentialism more than the idea of extrinsic, eternal laws, but I don't think this requires explanations of facts grounded entirely in the properties of "fundemental" parts.

Your question seems more akin to earlier questions about free will and it's compatibility with divine foreknowledge. This is a nonreductionist conception of determinism, and I think it is perfectly compatible with compatibilist ideas of free will.

Is the man free? It depends, freedom is relative. But he is not unfree simply because it was possible to predict his behavior. If we are, as Plato and Hegel suggest, more free when we are more united and guided by reason, then in key ways our actions should be more, not less predictable as we become freer (so long as you have information about the freer person's beliefs, priorities, and the information they have access to).

Saint Augustine used this analogy. Think of a choice you made in the past. Can you go back and change it? No, your choice is now a necessary element of the past. Does that preclude your being free when you made the choice, at the point of becoming? Absolutely not. We only make choices in the eternal "now," not in the "already has been," or "not yet." -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

It seems relevant to the Israeli argument re antisemitism. The question is:

- Given that there has been no shortage of wars in the region in the past 50 years; and

- Given basically every country in the region has participated in said wars to some degree; and

- Given most countries in the region have suppressed internal unrest using extreme measures (Syria, Iraq, Egypt, etc.); and;

- Given these military actions have generally involved significantly looser rules of engagement than Israel (e.g., both Syria and Egypt have hosed down large crowds of protestors with belt fed heavy machine guns in the past decades), and significantly higher death tolls (e.g. the Siege of Mosul involved 40,000 civilian fatalities despite being in a significantly smaller city against a significantly smaller occupying force);

-Why is Israel such a lightening rod for criticism?

Certainly, they are not exceptional for the region in how they treat a minority group, nor in their rules of engagement.

I think this argument has some limited merit. It seems fairly obvious that, historically, Israel has been used as a boogeyman to distract from the regional powers' own serious rights abuses and wide scale use of force against their people (often on significantly more intense scales than Israel). This does have something to do with the widespread antisemitism in the region that caused them to expell and expropriate all their Jews in the first place. And to the extent that Western media coverage gets guided by this as well (which it certainly does to some extent), there is a valid critique here. After all, would people have such passionate opinions about this conflict if it was occuring in Azerbaijan or Tajikistan and had similar dimensions? Obviously not. None of the much larger conflicts in the world over the last decade have produced marches (both for and against each side) on the scale we've seen in the West recently. The wars in Syria and Yemen produced no riots in Europe's relevant ethnic neighborhoods, no attacks on Sunni/Shia mosques to parallel attacks in synagogues, etc.

But not all of the elevation of the conflict in public discourse has to do with this phenomena. Part of it has to do with the religious salience of Israel for Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the West — and this phenomena also has the effect of boosting support for Israel, particularly in the US

Second, Israel claims to be a liberal democracy. This claim forces it to live up to a higher standard, and that has nothing to do with antisemitism.

Third, people often over estimate the gap between the the capabilities of the Israeli and Egyptian or Saudi armed forces. When Egypt just erases villages in the Sinai or the Saudis level areas of Yemen, people tend to think: "well they don't have the same precision capabilities." This actually isn't true. Egypt receives a massive amount of American military aid and has plenty of PGMs. They just don't choose to "waste" them in situations where leveling the entire community comes with minimal pushback. The Saudis spend a phenomenal amount on defense and have all sorts of high end American and Chinese precision weapons.

But perceptions are what matters, and people generally view these militaries as inept and corrupt (for good reason). The IDF has a much better reputation, which in turn increases perceived culpability for civilian losses and damaged infrastructure.

The "whataboutism" is relevant for an entirely different question then: why do people care so much more (one way or the other) about Palestine?

This is a question worth exploring because public opinion does shape the conflict. Would Hamas really think baiting Israel into destroying its own infrastructure and people was a worthwhile strategy if world and Arab opinion would be on a par with how people respond to other similar conflicts in the region? Absolutely not. Their strategy is in part predicated on the special resonance of Israel, and so it shapes their decisions in what seem to be fundemental ways. -

Does Religion Perpetuate and Promote a Regressive Worldview?

That's like saying an asexual person is simply someone denies the existence of sex. :roll:

No it isn't. The first is a term about sexual attraction, the second is about belief in God. E.g., the Oxford definition:

a person who disbelieves or lacks belief in the existence of God or gods.

What would your definition be?

I'm an atheist. Like many atheists I know, I don't deny the existence of god

IDK, that is the dictionary definition of the word "atheist." It doesn't mean you have to claim that God is metaphysically or logically impossible, but it's generally a claim about some level of certainty that God doesn't exist.

"Agnostic," is the term generally used for "undecided," or "the question is unanswerable."

Belief seems to me to be a bit like sexual preference. You can't help who you are attracted to.

I disagree with this entirely. If this was the case, and if you don't agree with the idea of "medical treatments to cure homosexuality," etc., wouldn't this imply that it is equally unwise to bother trying to change someone's beliefs? You can't "argue someone straight," but people change their beliefs based on arguments all the time. Imagine the bind we would be in if people changed their policy beliefs as rarely as their sexuality? What would be the point of antiracism and antisexism efforts then? Surely we convince people of the foolhardiness of racism more often than we "argue them gay/straight?"

I've heard plenty of people tell stories about leaving (or less often, joining) a faith after being exposed to arguments via books and videos. I do not know of a single person who ever claimed to have picked up a book and been convinced to turn straight or gay midway through their life because of it.

Side note: this is just one of the reasons why I think the Nietzschean argument, that "reason is just a desire," is incoherent. IMO, Nietzsche only seems to come up with this definition to avoid having to deal with Plato's arguments re reflexive freedom and freedom as self-control, since those crucially undermine Nietzsche's increasingly strong preference for the "Dionysian mode" over the "Apollonian" in his later work (Birth of Tragedy avoids this). -

Does Religion Perpetuate and Promote a Regressive Worldview?

This phenomena goes both ways. Plenty of people subscribe to some form of secular, atheist belief, having never really examined it or competing systems to any great degree. And many of these people, raised as atheists, come to join a religion as adults.

But in these cases, would we claim they weren't "really atheists," despite the fact that they denied the existence of God, because they never took any particularly close notice to how such a denial was traditionally justified?

I would think an atheist is simply anyone who denies the existence of God, regardless of whether they understand the God of theologians, what they are denying, or not.

How then do we classify "real" religious people?

I do see your point though. Most "apostates" tend to be people who were in x belief system by inertia from childhood and/or only at a surface level. That only makes sense. Those most motivated to embrace their faith and grow to understand it and it's history/philosophy are also those who are probably least likely to leave them for a whole host of reasons. Most important is likely the fact that, if you find something more convincing and meaningful, you tend to embrace it more and do more to learn about it. Those less convinced will be less motivated for this sort of effort.

But then again, you also often tend to find things more meaningful and convincing because you've taken time to understand it, so it seems the influence can go both ways. It's rarer to see historians of religion or theologians who radically depart from their faith, although it does happen. What you do see instead is a wider horizon from these folks, because most religions tend to have a universalist aspect, which makes it easier to assimilate and grow from other inputs. E.g., Thomas Merton, while a Christian monk, became a scholar of Sufi Islam and Zen in his quest to understand his own faith. -

Does Religion Perpetuate and Promote a Regressive Worldview?

I find the focus on fundamentalists very common in critiques of religion. They are, in ways, a ready built, real life strawman.

But Saint Aquinas was not a fundementalist just as Rumi was not a jihadi.

There is a common misconception that, because fundementalist believe in very simplistic, literalist interpretations of Scripture, they must be closest to what the faith was like in earlier centuries. This isn't true. There was, if anything, a much stronger tendency to read Scripture allegorically or analogically in the ancient Church, and really the Middle Ages as well.

Fundementalist, and the more literalist turns of more mainstream Evangelical churches is a modern phenomena. It certainly has echoes in prior eras, e.g. the fideists ("knowledge of God by faith alone") who Aquinas jousted with, but the juxtaposition of romantic, irrational faith and faith undermining reason definitely only comes into its own in the 19th century.

But this isn't a good generalization. Fundamentalists are vocal, but a slim minority. "Evangelicals" (in the sense used in the US today) are a very small minority in Christianity, and they aren't even a majority of Christians in the US (just a quarter). Catholics are actually now the plurality in the US, suprisingly enough (34%, vs 69% in 1950)

Partly, this has to do with self sorting effects. Religion now predicts income even better than race (shocking given the large differences in the US). It also predicts educational attainment quite a bit. It seems like a sort of "hollowing out," of your more educated population could lead to a sort of self fulfilling feedback cycle, whereby people less open to literalism (which education would tend to affect) end up being pushed out, leading to ever more "ideological purity," for lack of a better term.

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/15/magazine/is-your-religion-your-financial-destiny.html#:~:text=Overall%2C%20Protestants%2C%20who%20together%20are,being%20richer%20than%20Catholic%20nations

Partly -

Does Religion Perpetuate and Promote a Regressive Worldview?

This is an excellent point. It used to be that people looking for spiritual truths would abandon everything they had to live with some great teacher. Rigorous study, ascetic practices, long periods of meditation — these are the norm in the Jewish, Christian, Islamic, Hindu, and Buddhist traditions.

To be sure, these traditions allowed for other roads to enlightenment or spontaneous revelation. But in general, the truth required a great deal of study and praxis to ascertain.

But now the general take is: "beliefs about the most central questions if what being is and how we should live should be summarizable in five minutes."

Saint Augustine makes a related point, which is that we can never learn anything without trusting others. Our parents might not be our real parents. Our kids might not be our real kids, they could have been switched at birth. Anything we are taught could be bunk.

And yet, if you don't put effort in, assuming your physics textbook might be able to shed some light on the world for you, then you'll never get anywhere in understanding the subject. The same is true for theology, which is up with philosophy for most abstract disciplines. -

What are the philosophical consequences of science saying we are mechanistic?

"Mechanism," was view that all phenomena reduces to stuff bumping into other stuff, a view popularized by Galileo.

It's true that Newton's findings re gravity were sort of a death blow to this conception of the world. Gravity, for Newton, was a force acting at a distance. The original "mechanism" didn't allow for this.

Then, after the discovery of gravity as such a force, we began to figure out electromagnetism. This lead to a huge proliferation of supposed suis generis "forces," e.g., a special "life force."

But advances in the 20th century actually seemed to make something like mechanism more plausible again, although with major modifications. Even reductive physicalism today is still pretty different from the more simplistic view the original mechanists hoped for though.

So, the type of mechanism Newton disproved isn't exactly what we think about today. It was a view very much based on billiard balls crashing into each other, etc., which turned out to have issues. -

What are the philosophical consequences of science saying we are mechanistic?

:up:

It seems to me like plenty in physics, the life sciences, and complexity sciences are willing to take a broader view. The strong hold of the old mechanistic, smallist account of the world seems to be more a combination of inertia and the fact that no single succinct, easy to present alternative has shown up.

It's all well and good to show that the dominant paradigm is shot through with error, but what do you teach if there is no one solid replacement? That's where it seems we are at. -

What are the philosophical consequences of science saying we are mechanistic?

The human body with skin pulled back is obviously mechanical with muscle, bone and tendon obviously arrange to maximize the efficiency of mechanical tasks. This is however nothing compared to what we see at the molecular scale with molecular machines like Kinase, the myosin motors in muscles, ATP synthase and the bacterial flagellum. How neurons work is no less mechanical, with Ligand and voltage gated ion channels neurotransmitters. We know how neurons work individually and in groups like the 302 neurons of c-elegans. We know fare more than I am able to convey here.

Other than potential for quantum indeterminacy having an effect, science would suggest that even the brain is deterministic, even if know what it will do isn’t predictable. Even if you believe that the randomness of quantum indeterminacy can have a macro effect the effect would only be to inject some randomness into an otherwise deterministic system. Given this aren’t we as mechanistic, mechanical and as much a machine as any automaton, robot or computer?

I would note that in the first paragraph quoted you are looking at small parts of a person. I think most of our discomfort with "determinism" and "mechanism" comes from the fact that it is often wedded to smallism (the view that facts about big things are grounded in facts about little things) and reductionism. People tend to think that one implies the other, that you cannot have determinism without smallism. This isn't true.

Smallism and reductionism are in decline. I would say they are more popular in the general lay conception of "how science says the world works," then "how physicists and philosophers of science tend to think the world works."

If by "mechanistic," we simply mean "the world exhibits law-like regularities," then this is still a very popular take. However, this sort of determinism does not imply that every individual thing can be explained in reference its smaller (and thus presumably mindless) parts.

I personally don't like most conceptions of libertarian free will I have come across. If our decisions aren't "determined by" the way we are, and the way the world is, then it seems like they are arbitrary, random, and thus not free. Plato and Hegel seem to have the best popular definition of freedom I am aware of: freedom as (relative) self-determination.

That is, we are free when:

1. Our reason is able to unify our drives and desires such that we are a unified person, not at war with ourselves.

2. We understand why we are doing things and the consequences of our actions and choose them anyhow.

3. We want to have the desires that are effective in us.

4. We are not missing information that would make us act differently. We are not being manipulated.

5. We are our authentic selves, able to seek what we think is the highest good.

Determinism is not a barrier to free will in this sense. It is rather a prerequisite for it.

Many types of popular process metaphysics, e.g. pancomputationalism, aren't commensurate with smallism. Many theories in fundamental physics aren't smallist either. These are very popular with eminent physicists, and have the benefit of giving us new ways of looking at the metaphysics of free will.

The fatalism that comes with "natural determinism," then seems to be more an outcrop of the smallist and superveniance views of the world. E.g. "I am just the current molecules in by body and the rules for how these molecules work, (which is mindless), dictates everything about me."

I would agree that this is a depressing view. It also seems to be a hard view to support, for many reasons. To name just one, reductive substance metaphysics seems to deny the possibility of strong emergence (Jaegeon Kim, etc.). But then, where does first person experience come from? A view that seems to deny what is most empirically obvious to us seems critically damaged. Add in that there are many other reasons to adopt a process based metaphysics, to see wholes as sometimes more fundemental than parts, and to reject superveniance as a useful concept, and it seems easy (to me) to simply reject smallism, reductionism, etc., without rejecting the law-like nature of the universe.

But if we are hard to delineate processes nested in a larger universal process, I see no barrier to relative self-determination of the sort Plato, the Patristics, and Hegel are talking about. The bleak picture of determinism vanishes. It ends up just telling us that "we live in a world of regularities." It doesn't "disenchant" nature into a clock in the same way. -

The American Gun Control Debate

Right, it's a conflict between rights, namely a right to self-defense and a right not to be shot. The position is also often that criminals simply won't follow gun laws, so even if there are restrictions put in place, it will only effect the very people who are going to use their guns only for self-defense and recreation. I don't think this is a particularly good or well supported argument, but it remains popular because, on the surface, it is plausible enough if you don't dig too deep.

In fact, this argument does hold if you look at local level gun control. E.g., if Chicago does a lot to restrict fire arms access but Illinois does not, then criminals still have an easy time getting fire arms. There is an extra level of nuance in that smuggling across state borders is trivially easy, there are no searches at all, no check points, no declarations, where as smuggling across national borders is not at all easy. So the conservative argument ends up being true to some degree, but in terms of local gun control, not national.

The problem is that many factors play into homicides and suicides. The relationship between the ease of access to firearms and these problems is thus complex, and people have a hard time understanding the evidence in support of gun control. That this has become a "culture war" issue makes it even harder to make any progress. The US's antiquated electoral and primary system makes things much worse, since support for some gun control measures are quite robust, and yet they are still highly unlikely to ever be passed.

For policy folks, I think there is often a utilitarian consideration that this is one of the hardest places to make progress and that the change in outcomes you can expect is modest. That's another reason why it doesn't gain overwhelming traction. Homicide rates have fallen and remain historically low (in the US context) which takes the pressure off. The last time we had huge gun control overhauls, violent crime was much higher. -

The American Gun Control Debate

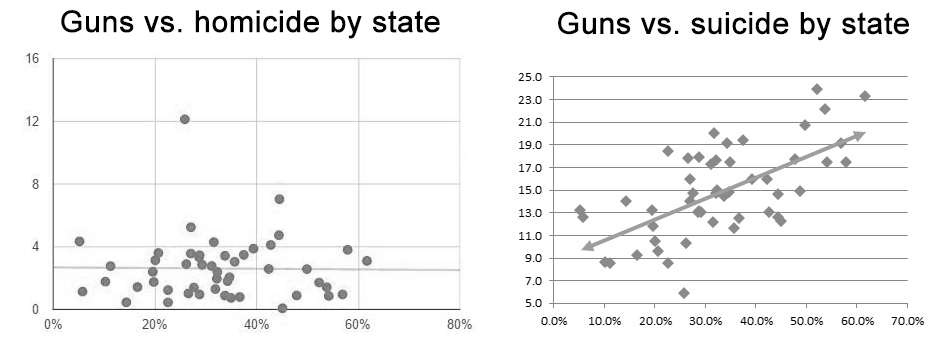

My response wasn't even originally in this thread. It has nothing to do with gun gun control as a policy. I was simply trying to explain the lack of a robust correlation between gun ownership rates and homicide rates. I've posted the scattered plots, I've corrected what you seemed to think was a study about the relationship between gun ownership and homicides.

I have no interest in defending the thesis that "gun ownership is not related mass shootings," the bailey you have decided to retreat to. Why keep insisting you're correct rather than just looking the simple relationship up (not some 20+ variable model answering a different question) and saying: "oh yeah, there isn't much of a relationship for US states or world countries, but that's because of variations in other factors (poverty, ethnicity, inequality, unemployment, etc.) overwhelm the effect. Gun control would still reduce the homicide rate."

That makes perfect sense to me. Things can be related without showing a strong relationship on a plot.

That’s it. Timothy knows all this, of course, but for some reason wants to avoid the basic question and instead focus on something that in my view is irrelevant.

How is: "does a greater share of households owning firearms lead to more homicides?" irrelevant to the gun control debate?

That seems to me to be the question at the heart of gun control debates. "If we let people have more guns, are they going to kill more people?" Homicide rates overall are what is relevant because of substitution effects. What good is it if banning guns causes firearm murders to fall, but then total murders stay the same or increase? Why would it be better to keep someone from shooting someone else if they will just stab or strangle them instead?

The same question comes up for suicides. We don't really care about "reducing suicides carried out with firearms," as much as "reducing total suicides." Some share of would-be suicides and murderers who are denied firearms will still carry out the same acts with different implements. This is even true with mass killings. If we thought that would be spree shooters would simply carry out as many and as deadly mass stabbings, what would be the point is banning guns?

What research tells us is that reducing access to fire arms appears to reduces certain types of homicide and suicide, and spree killings. But the relationship is complex and easily overwhelmed by other effects. E.g. in the model you shared, inequality (GINI), race, and general rates of violent crime overall were more predictive of firearms related homicides than firearm ownership itself. It doesn't suggest a super strong, direct, relations when the rate of people physically owning the type of murder weapon is less relevant for predicting homicides with that type of weapon than variances in income.

Which isn't to say gun control might not be a worthwhile policy, but it also shows it is unlikely to be the key to reversing the United States very high homicide rate. -

The American Gun Control Debate

First:

We observed a robust correlation between higher levels of gun ownership and higher firearm homicide rates.

This is not saying: "If more people have guns, they are more likely to commit homicide." It is saying the "if more people have guns, there will be more homicides involving guns." In general, the policy question people care about it: "will more people be murdered?" Not "will more people be murdered with guns (pulling out variations in the homicide rate)?" The model they are using uses the homicide rate and violent crime rate as control variables.

The fact that, if people have more access to firearms, more murders that are committed will be committed with firearms seems trivial. No one commits murder with a weapon they don't have. That has nothing to do with my point, which is that the straightforward relationship between gun ownership rates and the general homicide rate does not show a robust correlation.

Second, you're quoting a paper on using 22 control variables in a negative binomial regression, modeled using GEE because the distribution is non-normal. So, regardless of the merits of such a complex model, it doesn't change the fact that it's not going to track with public perceptions.

People think: "well, Idaho, New Hampshire, Vermont, Utah, Iowa, etc., they have lots of guns and violent crime is on par with Europe."

Not: "well, if I control for race, ethnicity, age, income, the crime rate, inequality, non-firearm murders, suicides, hunting licenses, alcohol use, unemployment, etc..."

Not my area of expertise, but pulling out all the variance associated with violent and non-violent crime rates, and non-firearm homicide rates seems questionable to me, but that's sort of beside the point. I mean, is "holding violence equal, if people have more guns they will do more of their violence with guns" really a point of contention? -

The American Gun Control Debate

It's possible; I've never seen it looked at that way before. Although, I imagine if the relationship was significantly stronger it would be a more common statistic invoked by activist. Generally, the analysis looks at the percentage of households with at least one firearm versus homicides. There is a pretty strong overlap between households that own at least one firearm and those that own handguns, although it isn't absolute by any means.

Basing it on the total number of firearms doesn't make a lot of sense, since a relatively small group of consumers account for a large number of total firearms. Plus, the relationship doesn't seem strong. US violent crime has plunged since the 1990s, remaining low despite a bump during the Pandemic, even as the quantity of firearms has surged.

It'd be interesting to see what that data looks like though. Rifles tend to not be used in very many homicides. I believe less than unarmed murders or those using weapons other than firearms. But obviously they are justifiably a focus in the mass shooting debate. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

“Where else do they force a little child to crawl with a backpack on his back? When Hamas treats its children like this, Israeli parents tut-tut with disgust: Look at these beasts.”

Oh, we do it here. Prep for our weekly/monthly mass shootings... :confused: -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

A bold choice for a dictatorship that won a slim plurality in a single election almost two decades ago to make for their people. Especially when so much of the leadership is safe from any of the privations of the war. -

The American Gun Control Debate

I've already posted the correlations between homicide rates and gun ownership, for the OECD, all nations, and all states. Your links are about different things (mass shootings, all gun deaths - including suicides, etc.). Your other chart on "gun related deaths," is the same thing. They don't show anything different from what I've already said re: "gun deaths vs homicides." But gun control is generally seen first and foremost as an issue related to assaults and homicides, and that is where the relationship is not straightforward.

There are more than twice as many suicides as homicides in the US, so the inclusion of them isn't ancillary. The suicides make up like 70% of the data points. Hence why the two images below look so different (homicides vs gun ownership vs gun deaths vs gun ownership.)

-

Reflections on Thomism, Kierkegaard, and Orthodoxy: New Testament ChristianityBTW, the promise of mystical union with the divine seems to be a major part of the "Good News," that is neglected in contemporary accounts of the Gospel. Instead, Christianity is reduced to a story about how one avoids punishment and gains reward. Christianity as a path to freedom — freedom over circumstance, desire, and instinct — the sort of unification of the will Plato and Hegel talk about, is particularly neglected.

As Saint Athanasius famously put it (quoting Saint Irenenius): "God became man that man might become God."

This isn't an elevation of man, but rather a transformation and union. Saint Paul stalks about "putting on the new man." Christ talks about being "reborn." The result is Christ as a bridge to the Divine Nature, through the Spirit. Saint Paul, Saint John, and Saint Peter all talk about "God living in us," "living in God," "Christ living in us," "I must decrease and Christ must increase," etc. We hear of living in the "fullness (pleroma) of God."

I also tend to agree with Tilich that competition with Islam (and later the Reformation) wounded the universality of Christianity. It became "one religion among many," as opposed to a universal, non-religion. The Patristics' sense of Christ as Logos had it that all knowledge was ultimately grounded in the divine. It was so easy for them to assimilate Platonism and Aristotle. The Logos was present in all cultures and religions, and all men craved the "true good," the "real truth." This sort of universalist self-confidence has been badly damaged though. You still see it in later figures though, Erasmus, Cusa, Boheme, Zwingli, Hegel, etc.

Thomism is probably a place where that sort of sentiment survives. -

Reflections on Thomism, Kierkegaard, and Orthodoxy: New Testament Christianity

The third and final part will discuss how these positions are similar to Orthodox Christianity and ultimately conclude with what Catholic and Protestant thought are lacking in and that is an emphasis on mystical theology.

What do you mean by "mystical theology?" I find this to be a tricky term. Is mysticism just "experience of God?" Something like "knowing God the way a biographer/historian knows a person" (theology) versus "how their spouse knows that person," (personal/mystical)? This was Jean Gerson's expansive view in the 14th century, one used by some modern scholars, e.g. Harmless.

Or is mysticism about ecstasies, peak experiences, and visions, as William James would have it?

Or is this the "mystical theology," of Pseudo Dionysus (Saint Denis), an apophatic revelation of the "Divine Nothingness?"

It seems to me like the mystical tradition is generally much weaker in Protestantism. When it does manifest, it is much more often as more concrete, supernatural experiences: exorcisms, healing, visions, etc. I tend to be skeptical of these, both because of the historical ways they have been revealed to be hoaxes and because of my personal experiences with people who seem to be more living out a sort of self-serving fantasy life for themselves in this way, although I'm sure this isn't always the case.