Comments

-

Doing Away with the Laws of Physics

I immediately thought of Cartwright with the OP here.

To expand on the above and the very good point made here: , the "laws of physics," are not the actual rules that govern how observed phenomena work.

For example, Newtonian laws for classical scale objects are not how those objects actually work. They are idealized systems that approximate how two discrete, isolated objects interact. In reality, no such objects exist such that they only influence one another and are composed of a unitary whole. Add a third body into the mix and Newtonian laws break down (hence the "Three Body Problem" popularized by the sci-fi book).

Likewise, a lot of our models involve sticking in all sorts of contestants and fudge factors to get "accurate enough," predictions, but these are by no means the way the world actually appears to work according to our observations.

We assume perfect geometrical shapes in models all the time, but these are nowhere to be found in reality. Mandelbrot has a lot of interesting ideas on this. A core one is that objects don't have just one set of dimensions. A call of string seen from far away is just a single point. Get closer and it becomes a 3D ball. Get closer still and you have a 2D line. Move even closer, to the smallest scales, and you're back to 1D points.

Similarly, he claimed the length of the British coastlines is infinite. Measure it with a mile long ruler and you get one answer. Measure it with a foot long ruler and you get a longer answer because now you're taking account of all these tiny inlets and bends. Get even closer and eventually the static coastline disappears entirely and becomes a roiling mass of molecules.

I feel like this is an important point in reference to your original post because it shows we shouldn't be thinking of them as "laws" in your original sense in the first place. So, sort of a different path to the same conclusion you had. -

Speculations in Idealism

Yes, that's a fair point. Hoffman's "Conscious Realism" could be aptly labeled "Conscious Idealism." It's saying that the things we want to talk about 90+% of the time don't exist outside our minds. In my opinion, the conclusions one is forced to draw if they accept his argument are largely in line with those of idealist ontologies, at least in terms of how we should think about the phenomena of experience (including scientific observations). However, there is an important caveat that, hidden away at the ontological basement of being, there is this rather mysterious "other," we're grounding our view in.

The interesting thing is that it is empiricism and the advancement of science that leads us to this weird place. Another interesting trend is that different authors seem to be reaching similar conclusions about what the observations of science are telling us about reality from two distinctly different angles: the lens of physics and the lens of cognitive science/neuroscience.

Now, how big of a problem is this mysterious other in terms of a consistent ontology? How fundamentally different are these two different things, the world of appearances and this "other" and how do they coexist? I think these are unresolved questions and people are right to feel unhappy with the conclusions of the theory in that it doesn't give satisfying answers to them. But it's not all bad news, if you like philosophy, it shows that the field may still have some relevance yet! (And relevance to science too, as working out ways to deal with the issues highlighted could be crucial to answering some of our biggest scientific questions; that is after all the whole point of the theory). -

Speculations in Idealism

The question is if anyone there would see a snake what could it even mean to say there "really" is no snake? If we say it's "really" just a configuration of energy or fundamental particles or fields or "something" atemporal even beyond those things, how would such judgements not be every bit as derivative of and dependent on our perceptions as the snake or the selection pressure for that matter?

I feel like this is similar to the objection raised earlier. Saying something cannot or is highly unlikely to be right does not require you to know what the correct answer is:

Hoffman goes through the objection I think you are getting at, i.e. that his argument is self refuting, in his book. "If you say we don't know the real world, how can you know we're wrong?"

The answer is that the logic of his argument is "if p then not q." This does not require one to have a full, absolute definition of p. "-X * -X is a positive number," does not require one to have defined X. The logic of multiplication is that two negatives multiplied together produces a positive number.

The logic of his argument is the same. Fitness versus truth theorem is saying that natural selection will favor representations geared towards representing information in terms of fitness. You don't need to define what truth is to have a theorem that says selection will favor representations that do not favor it.

One example he uses is a simulation where a "critter" has to find food to survive and reproduce. One set of critters sees the absolute value of food in each cell they can move to. The other sees only a color pallet, darker if a square has more food than the one it is currently on, lighter if it has less food than their current location. This second model gets the critter more useful information with a fraction of the information.

And this is also how our sensory systems actually seem to work. Wear color shaded glasses and your perspective will quickly adapt to them.

See above and the earlier part of the post:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/715874

He takes a que from Daniel Dennett's "Darwin's Dangerous Idea." The core idea there is that, regardless of whether the central dogma of genetics holds up, or even the entire field of biology, we nonetheless have a theorem of how intricate complexity that seems to suggest a "designer," can come about with no such designer. The concept of natural selection works just as well for understanding why we see the types of physical things we do as it does for evolution. We don't see exotic matter (composed of four and even five quarks) because it isn't stable. This is also why we don't find certain elements or molecules in nature. Ockham's Razor suggests natural selection over design when it comes to complex systems.

The theorem of natural selection, "Darwin's universal acid," can explain selection even if most of what we think we know about the world is wrong.

The only thing you need for this sort of selection is the assumptions that:

1. Living things can die

2. Living things inherit traits

3. Living things can only store a finite amount of information, less than the total of the enviornment and have finite computational capacity -

Speculations in Idealism

He sometimes gets dangerously close to the line of undermining his own argument at times, at least by my reckoning. However, overall I think he has a valid argument and summons plenty of good evidence to support it.

For me, part of the apparent "self-refutation," appears to have been due to unexamined assumptions I had absorbed in my studies. I didn't have the ability to easily parse out natural selection as a general theorem from the physicalist ontology that comes with modern biology as extra baggage. I found myself thinking the same thing at that part of the book: "what snake?" But the failure here, for Hoffman anyhow, is due to my assuming that a "real threat to fitness/real selection pressure" = physicalism and all it entails, or that it at least entails all the entities of biology existing as they are currently put forth in the mainstream view.

However, there is no logical reason that you can't have a selection pressure that is constructed by the mind as a "snake," and still have no snake. Sort of how the altimeter of a plane isn't its actual altitude and its hitting zero isn't the selection pressure of the plane crashing itself. The altimeter might be the only information a pilot has access to at night. The argument is that weare flying at night and mistake the altimeter for the ground itself.

Which at least isn't contradictory. How convincing the empirical case is will probably vary between audiences. -

Time Entropy - A New Way to Look at Information/Physics

Perhaps what you have in mind are past microstates that, when evolved into the present, would be consistent with the present macrostate? In other words, past microstates that evolve into any of the microstates that partition the present macrostate.

Now, let me backtrack a bit and reexamine your definition of entropy. A given macrostate induces a particular statistical distribution of microstates. When a system is at a thermodynamic equilibrium (and thus at its maximum entropy), all its microstates have the same probability of occurrence. Then and only then can we calculate the entropy simply by counting the number of microstates. In all other cases* entropy can be calculated, per Gibbs' definition, as a sum of probabilities of microstates in a statistical ensemble. Given a time discretization, we can then add up past microstate distributions leading to the present distribution to obtain your "time entropy."

Am I on the right track?

Yup, that's the main way I thought of it. I also thought of it in terms of the macroscopic variables in the past consistent with those in the present, but this seems to run into immediate problems:

1. No system is actually fully closed/isolated so backtracking the macroscopic variables seems impossible in practice on any scale that would be interesting.

2. If I'm thinking this through right, an idealized isolated system's macroscopic variables shouldn't change at all over time unless the system is contacting or expanding.

The "past microstates that, when evolved into the present, would be consistent with the present macrostate" conception seemed like it could be more interesting when I wrote the thread. For example, the whole idea behind Leplace's Demon is that the full information about the actual microstate also gives you total information about all past states. This makes me think that you should be able to show that knowledge about the distribution of possible states in the present should contain all the information about the possible past states, but I'm not sure if that actually holds up. -

On the Existence of Abstract Objects

They're both discrete ideas, or at least discrete enough ideas that we can give shorthand names to them. I can use the words "dog," "color," "hollow," "key," etc. to represent ideas specific enough that the vast majority of things I could be referring to are eliminated as potential references.

When the first key cards were rolled out at hotels it wasn't a huge conceptual leap to explain them to people because "key" was already a discrete idea they had a lock on, even though they look and function very differently. Similarly, it I tell someone who wants to help me that I'm looking for "my car keys," they eliminate the vast majority of potential things they could see from consideration and have a decent idea of what we're looking for.

That's my take anyhow.

lol, great term -

Speculations in Idealism

So, the corollary here would be "I believe in physicalism, but I don't know if physical reality exists?"

This seems different to me because it is a positive claim made in the absence of knowledge as opposed to a negative claim such as: "I don't believe in physicalism, but I don't know if it is true or not." -

Speculations in Idealism

I still need to earn money and be careful crossing the road, behaving as though physicalism is all there is.

Sure, but this seems like the opposite of your atheist argument. If the existence of God / the physical nature of reality don't have any practical import, and if no evidence supports their being true over their not being true, wouldn't it make more sense to be agnostic?

Anyhow, to come fill circle, I think the rationale for this sort of speculation, aside from being idle navel gazing, is that assumptions tied to our ontology bleed into our methodology and science whether we like it or not. This is probably even more true in we don't critically examine our ontology, but instead pick it up by osmosis, as a default.

As an example, absolute time was an assumption of materialism in the Newtonian era. It appeared to be a fact verified by a great deal of data and experimentation. Einstein's great insight re: relativity was to identify this fact as arbitrary, simply grounded beliefs about the nature of reality.

Ideas about "how reality is," work their way into science all the time. After the paper on special relativity Einstein rewrote his equations to include a constant that would keep a static-sized universe from having all its mass collapse back in on itself. This ontologically motivated addition has stayed ever since, even after the idea that the universe was expanding became mainstream, and now it has a second life in conceptions of the "metric field," and the weight of empty space.

Similarly, biologists found themselves in a bind due to the elimination of formal and final causes from consideration on the grounds that "all that exists is the elementary units of physics and the rules of their interactions." This reduced formal and final causes to useful mental shortcuts at best. Increasingly there is pushback on this. The prohibition of these being "real causes," stems from ontological commitments. -

Speculations in Idealism

And what is the evidence that that supports the position of ontological physicalism in the first place? Does anything make it the default?

What would constitute evidence of something supernatural? If tomorrow someone made a giant breakthrough in M theory that made amazingly accurate predictions about our world and:

- The theory also included "soul particles" that enter our dimension from another dimension and suffuse conscious entities; and

- Experiments based on the theory that aimed to confirm (at least to the standards of top scientific journals) the existence of the soul particles did indeed appear to confirm the existence of the particles, their extra dimensional nature, and the fact that they only enter our world in relation to intelligent entities;

...wouldn't people just claim that "well yes, of course soul particles are physical, look at this evidence for them." Likewise, we have a lot of experiments that have verified that an observation of one thing can instantaneously affect another thing at any distance; this non-locality is now considered physical. We also have a few experiments that seem to suggest that there is no one objective description of events at a fundamental level, that is, which observer you are determines what you observe. If these results do keep piling up, I have little doubt that "the lack of a single objective, public world" will also be considered physical. This is Hemple's Dilemma.

Point there is that asking for evidence of non-physical phenomena doesn't work when the definition of physical expands to include all phenomena we think we have good reason to accept. Historically, this is what has happened. But any other ontology can just as easily do the same thing. -

Speculations in Idealism

I don't think these are analogous. One about God is saying "there is no evidence for X, so even though X can't be excluded by necessity, it does not make sense to believe that X is true."

The formulation re: physicalism would be: "There are no solid reasons to accept Q, R, S, etc. (other ontologies) so we should accept X."

The problem here is that the same arguments for why Q, R, and S can't be shown to be true all apply for physicalism. We know there is a reality, hence the formulation of ontologies. I don't see how you make the argument that "unless other ontologies can prove they are true, we should go with physicalism." Why is that ontology the default we need positive evidence to move away from?

They may be. If they are factual truth-claims, then there are truth-maker facts to which they correspond. Thus, they're expressions of science, not philosophy.

I totally agree. The truthmaker for solipsism would be that the solipsist's mind is indeed the only mind that exists. The truthmaker for subjective idealism would be the lack of anything existing outside of experience. Other minds existing is a state of affairs. The Milkyway rotating in space even when there is no first-person awareness of it would be a state of affairs. How is the claim that "things do not exist without experience," different from "smoke does not exist without fire," such that one is a claim/proposition and the other is not? I'll allow that one does not seem falsifiable, but that doesn't mean it can or can't correspond to reality.

So, I don't think I understand your objection. -

Speculations in Idealism

So:

"Everything in the world is Brahman and is caused by Brahman."

"Only things that are experienced actually exist. If no one is around to see the Moon it ceases to be."

"Only my mind exists. What appears to be other people, with other minds, do not actually exist."

"The world we experience is a simulation run by advanced AIs who use our body heat to generate power."

None of these are claims? The existence or non-existence of other minds isn't a factual state of affairs that can make solipsism true or false?

Ontologies are definitionally sets of claims. I'm giving the definition because they are defined by the claims they make. -

Speculations in Idealism

I don't think that's the same thing. Physicalism is an ontology, it's an explicit claim about the nature of reality. Epistemological/methodological considerations stand beside that. If "the physicalist who is a methodological naturalist doesn't make truth claims about the nature of reality," then in what way is their position physicalist?

You can claim the ontological question is meaningless metaphysical mumbo jumbo, or just not worth debating, but then you're not arguing for physicalism anymore. "Epistemological physicalism" or "methodological physicalism," do not make sense as concepts, they're conflating two different things, "how you can gain knowledge of the world," and "how reality is."

At their worst, those titles represent a bait and switch, where arguments are offered up in favor of the methods of science, and then the successes of the methods science are offered up as evidence for physicalism. At their best, the "physicalism," part of the term is just superfluous.

But obviously you can be a physicalists, not want to debate ontology, and advance methodological naturalism. That makes perfect sense to me; you just pass over the questions you don't think you can answer. -

Speculations in Idealism

Rarely. But it can work well enough for cross disciplinary analysis of scientific findings. You can still see how different models fit together and what their implications are even if you're working with faulty premises. That said, handwaving these epistemologicaly issues aside also does lead to bad reasoning in many cases.

Wilczek's "The Lightness of Being," is a good example of when this works well. He notes that quarks only exist as a mathematical structure. "The bit is the it," as he puts it. However, he explains quantum chromodynamics using analogies to objects that do occupy space in our perceptions (colored triangles, etc.) The goal is to give readers an understanding of QCD and local vs global symmetries without them having to understand the complex mathematics undergirding the theory. I think this is a fine aim. I think I might still have been lost if I hadn't already taken a course on the topic, but I feel less lost than I did then because he's presenting the information in a way that is more accessible even if the examples contradict the metaphysical position he's also asking us to take re: abstract objects being the foundation for physical "stuff."

I've not said or implied anything about "meaning" so referring to "verificationism" is a non sequitur.

I am referring to:

"Idealism" (like materialism, etc) is neither a formal theorem nor a factual truth-claim so the question is incoherent.

Physicalism is a factual truth-claim. It's the claim that the physical, which is mind independent, is ontologically more primitive than experience; that the physical supervenes on everything that is. Arguably this definition is too broad to be particularly meaningful, but generally physicalism also entails the claim that physics (once completed) provides a full description of "what is," and that this description holds regardless of whether there is anything around to observer said being.

Idealism has a more squishy definition. We could say it is the claim that: "things do not exist outside the experience of them." This doesn't cover all forms of idealism but works well enough for showing it is a factual claim.

The truthmaker for physicalism would be the existence of the universe described by physics in the absence of experience. This seems to me like a truthmaker that is possible (I suppose many idealists would say it is not), but not observable. Is your argument that claims about "what being is like" outside of experience are incoherent?

I'll allow I do find those arguments somewhat convincing.

Most common versions of physicalism would agree that a truthmaker for their claim would be that, long before any experiencing thing had time to develop, stars were doing what physics describes them as doing, fusing hydrogen into helium and giving off light.

Idealism is harder to pin down, but the version put forth above is a negative claim. If nothing exists outside experience, then idealism would have a correspondence with facts of the world.

IME, Count, philosophy consists (mostly) of pre/suppositions (i.e. interpretations, meta-expressions, aporia), not propositions

Maybe it should, but I'm not at all certain it does. Philosophers seem to make plenty of propositions. They make whole books of nothing but numbered propositions.

As in....reinventing them so they can be known? Then they wouldn’t be Kant’s noumena, then, right? So it isn’t so much reinventing as re-defining. Which is fine; happens all the time. Historical precedent and all that.

No, I say "reinventing," because it is the same paradoxical issue. Our perceptions are about the noumenal world, but we can never know the noumenal world as it is, full stop. Seems like the same problem to me. -

Speculations in Idealism

A truthmaker is not evidence. It's a state of affairs.

Exactly. And physicalism could indeed be a state of affairs even if solid "evidence" for it cannot exist due to the fact that all such evidence comes in the form of first person experiences.

This implies the dubiousness of correspondence theory, and why it's not a popular theory of truth.

It's not? It seems to me like the most common theory I've seen. It's either in its pure form or wrapped up as pragmatism. A paragraph or two is spared to identify that the author is aware of issues with the correspondence theory, they invoke pragmatism, and then promptly carry on using what is essentially the correspondence definition for the rest of their work.

And I can't totally blame them because for many topics it is the most straightforward definition to use.

The more I think about it, most versions seem to be evolutionary epistemology plus reinventing Kant's problem of a noumena that we can never know. Same problems, different environment lol.

We'll need to wait for scientific Hegelianism to emerge to rectify this. -

Speculations in Idealism

Because it's not possible for there to be a truthmaker or because it's not possible verify the existence of said truthmaker?

It seems to me like there is no logical reason a truthmaker for physicalism cannot exist. A physical thing existing in the absence of mind does not seem necessarily impossible. Likewise, idealism is the claim that what people call physical things don't exist without minds. There appears to be a possible falsemaker for this negative claim.

It seems like for this:

Idealism" (like materialism, etc) is neither a formal theorem nor a factual truth-claim so the question is incoherent.

to hold you need some other premises such as: "only knowable factual truth-claims have meaning," i.e. something like verificationism. Logic doesn't necessitate that the truthmaker for physicalism cannot exist, it only entails that it cannot be known. But unknowable truths seem like they might be around anyhow (e.g. Fitch's Unknowability Paradox).

The other problem in that case is that the limits of knowabilty seem to move around quite a bit on us.

I don't think he has rejected the idealist label, but I also don't think idealism = anti-realism. I agree with the SEP article that idealism is more often defined by "what it is not," and that seems to hold Hoffman's model. But it's also possible the he puts forth a quote different model in other places, people's ontology changes.

But maybe the issue here is that we're not clear on terms.

By realism I mean simply the idea that there is something "out there" which has a casual role in perceptions. I put Hoffman in this bucket because he repeatedly stresses that he does believe there is a "something" outside the mind. It's also the case that his entire argument makes very little sense if you hold that there is no reality outside the mind. What then would be the point of references to evolution, apparent illusions, etc.? A core premise of his fitness versus truth theorem is that there exists a tradeoff between more and less faithful representations of "things," and this is true regardless of whether fully faithful representations are actually possible (his claim is that they are not, in part because the entire question is framed wrong).

I would place him with Schelling and Hegel in this respect. For them, nature was an actual entity, it was merely the objective/subjective dichotomy that was false (somewhat similarly to Shankara, but without the problems of seemingly falling into an excluded middle).

Hoffman, like Hegel, would be a fallibleist, in that we, as individuals, can never come to know a "thing-in-itself." The entire idea of the noumena becomes nonsense because "things-in-themselves" don't actually exist. The discrete objects the idea entails are an illusion foisted on us by our evolutionary heritage. Hoffman seems to embrace models of a participatory universe, which entail that what we think of as things only exist as sets of relationships, i.e. what "things" are in terms of something else.

This might fit certain definitions of anti-realism because it makes our propositions not references to actual entities. But in another sense it is realist because it definitely posits a "something else," outside perception. This is like the difference between Advaita Vendanta and Absolute idealism. Everything experienced isn't falsity as in Advaita, you don't have this reduction where Brahman is the sole ontic entity, the "something else," has an ontic status. Indeed, Hoffman's whole goal per the introduction is to help us move past misconceptions and gain better understanding of that something.

Since the book isn't centered around philosophy, I can't really say if there is a contradiction here. It seems like he might be falling into the same sorts of trouble Kant had with his unresolved semi-dualism. It might also be that he played down a more anti-realist position in the book to make it more accessible, or that he developed those positions later. That would certainly make sense if he looked at his model and said "damn, I recreated Kant's incoherence."

Finally, you do need a definition of real and true if you set out to deny them

I covered that in the post with -X * -X <> any positive number. He includes the formal logical proof for FvT Theorem. You don't need a definition of something to say what it cannot be given simple premises, otherwise formal logic would be useless.

Color tests are tricky but in the real lived world apart from electronics someone with good eyesight can tell what a true color is.

But this is not what we see in experiments on color discrimination. The ability to discriminate between colors changes with age, varies by person, varies by gender, and crucially for the argument, varies significantly with context and exposure to other colors. In terms of remembering color, the native language of a subject and how said language categorizes colors effects how well they can remember color differences. -

Speculations in Idealism

Throughout his book he refers to his belief that there is "something" out there. That to me bespeaks realism. I'm not sure if his opinions have since changed, but I don't see how that quote would necessarily rule out realism. In Wheeler's participatory universe and later iterations by other physicists there are not definite "objects" or "space" before observation/interaction, but observation also doesn't generate what it finds wholly on its own. There are rules as to how the actual emerges from the possible through these interactions (allowing that they are still incomplete models). So that "something" is very strange in comparison to naive realism, but it is also still quite far from a model where the self wholly generates that which it finds around it. -

Speculations in Idealism

Hoffman is a realist. As a scientist, he's not going to get hung up on metaphysical challenges to the existence of the external world. His goal is to challenge unexamined assumptions about that external world.

He takes a que from Daniel Dennett's "Darwin's Dangerous Idea." The core idea there is that, regardless of whether the central dogma of genetics holds up, or even the entire field of biology, we nonetheless have a theorem of how intricate complexity that seems to suggest a "designer," can come about with no such designer. The concept of natural selection works just as well for understanding why we see the types of physical things we do as it does for evolution. We don't see exotic matter (composed of four and even five quarks) because it isn't stable. This is also why we don't find certain elements or molecules in nature. Ockham's Razor suggests natural selection over design when it comes to complex systems.

The theorem of natural selection, "Darwin's universal acid," can explain selection even if most of what we think we know about the world is wrong.

Hoffman assumes the external world exists because all empirical evidence tells us it does. He is looking for fundemental flaws in how our senses represent the world because empiricism has also show us that our senses mislead us about reality at a fundemental level, and the history of science has shown us how our preconceptions have frequently allowed us to miss answers right in front of our faces.

With those as a given, the only extra assumptions you need for the theory he is testing is:

A. The enviornment (everything except the organism), contains more information than the organism does.

B. The organism cannot store an infinite amount of information and lacks an infinite amount of processing power.

There are, of course, objections to the reality of the physical world that don't seem resolvable. He is rejecting radical skepticism in that sense.

Hoffman goes through the objection I think you are getting at, i.e. that his argument is self refuting, in his book. "If you say we don't know the real world, how can you know we're wrong?"

The answer is that the logic of his argument is "if p then not q." This does not require one to have a full, absolute definition of p. "-X * -X is a positive number," does not require one to have defined X. The logic of multiplication is that two negatives multiplied together produces a positive number.

The logic of his argument is the same. Fitness versus truth theorem is saying that natural selection will favor representations geared towards representing information in terms of fitness. You don't need to define what truth is to have a theorem that says selection will favor representations that do not favor it.

One example he uses is a simulation where a "critter" has to find food to survive and reproduce. One set of critters sees the absolute value of food in each cell they can move to. The other sees only a color pallet, darker if a square has more food than the one it is currently on, lighter if it has less food than their current location. This second model gets the critter more useful information with a fraction of the information.

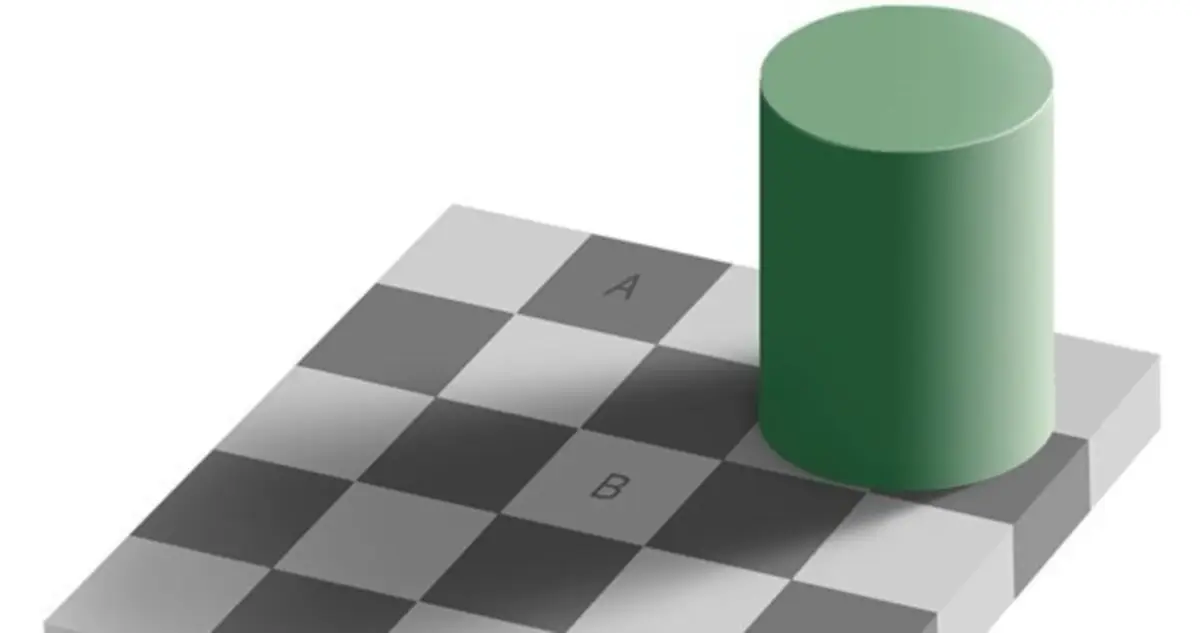

And this is also how our sensory systems actually seem to work. Wear color shaded glasses and your perspective will quickly adapt to them. Look at the picture below and you'll see square A as a different shade from square B. In a truth based system, they should appear exactly the same because they are the same.

This is all psych 101 and not terribly interesting. The more unique idea is that discrete objects, three dimensional space, etc. is simply a more deeply engrained illusion. Science is hamstrung by these persistent illusions and our tendency to project models that work with our perceptual system into reality. Thus we'll look for how neurons cause minds and forget that neurons aren't actually discrete systems and that there is no evidence that they produce anything like minds without glial cells, CSF, oxygenated blood, etc.

I think he is missing something though. Given the enviornment can change so drastically, it would seem to me that there would be merit in anchoring perceptions closer to truth somehow. I think this might be why animals evolved discrete senses that are processed separately from one another and experienced quite discretely.

He gives synthesesia as an example of how our senses don't reflect reality. The argument goes "if the number four is blue for some people and the shape of a triangle is rough textured, this shows how far off our senses can get." He sees these as an advantageous adaptations because many artists and people with high intelligence have them.

I don't think it is so simple. I think our senses are kept separate for a reason. Our senses are kept discrete as a way of cross checking perceptions and getting closer to reality (even if we still don't get very close.) If you perceive yellow as "light and airy," you might carry something yellow you might otherwise not and waste precious calories because your sense of sight is too entangled with your sense of touch. Deception is common in nature and discrete senses help ferret out deception. A bug might look visually identical to a stick to a predator, but their hearing might be able to detect the insects' internal moments and allow it to score those calories by eating the insect nonetheless.

That said, this anchoring doesn't have to keep us very close to reality, it just keeps us close enough. -

Speculations in Idealism

I haven't looked in his models in any depth, but I can see how it works if you have the condition that an organism looking for resources so that it can reproduce can only store a finite amount of information about its environment.

If the amount of information in the enviornment exceeds that which the organism can store then the organism must have some method for compressing information.

Likewise, if the organism has finite computational power than it will also need to optimize how it compresses information about its environment.

Already we have established that the organism won't represent the enviornment with full accuracy. The next step is to see if the compression methodology will hew towards as accurate a representation as possible or one optimized for fitness. This is where the game theory models and computer simulations come into play in that they show how more complex organism will find optimal solutions that move further away from lossless compression and towards compression techniques that are optimized for reproduction.

It varies by person. Fichte starts with the apparent self. Schelling and later Hegel start with being itself. I think the latter approach is the best technique. How do you get anything more ontologically basic than being itself? -

Speculations in Idealism

it doesn't make sense to say "perceiving is perceived"

How so? It's bad writing to say, "I experienced experiencing the pain" but it isn't illogical. -

Speculations in IdealismFor another example of an "immaterial" ontology there is the claim that reality is fundamentally mathematical. Talk of "physical" structures is then extraneous. Unlike many other forms of idealism, this analysis does not start with the self/subjective experience.

What I find interesting about this is that one of the attempts to provide a fully scientific metaphysics: Every Thing Must Go, walks right up to this line, almost states it as an apparent fact, then opts to shoehorn the "physical" back in:

According to OSR, if one were asked to present the ontology of the world according to, for example, GR one would present the apparatus of differential geometry and the field equations and then go on to explain the topology and other characteristics of the particular model (or more accurately equivalence class of diffeomorphic models) of these equations that is thought to describe the actual world. There is nothing else to be said, and presenting an interpretation that allows us to visualize the whole structure in classical terms is just not an option. Mathematical structures are used for the representation of physical structure and relations, and this kind of representation is ineliminable and irreducible in science...

What makes the structure physical and not mathematical? That is a question that we refuse to answer. In our view, there is nothing more to be said about this that doesn’t amount to empty words and venture beyond what the PNC allows. The ‘world-structure’ just is and exists independently of us and we represent it mathematico-physically via our theories.

That's a head scratcher; it certainly recalls Hemple's Dilemma.

The only subjective idealist I am all that familiar with is Berkley, and for him these are tied together by the mind of God. My intuition is that these systems would tend to be very idiosyncratic. -

Speculations in Idealism

I don't see how that works. You still have a world full of concepts, symmetries, cause and effect, etc. Why this plethora of entities and endless variety instead of nothing?

If the world around us shows us causes preceding effects it is natural to ask: "what causes things to be?"

What the Boehme inspired idealists try to do is show how being emerges from logical necessity. You don't need a demiurge shaping the world based on some sort of Platonic blueprint, you just need for there to be something and not nothing. This then sets up the being/nothing contradiction, resulting in our experienced world of becoming. The rest, all the differences and possibilities of our world, flows from logical necessity.

Hegel takes this to its most complete form, having physical science, cognition, and history flowing from this necessity and progressing to the point where all being becomes known object to itself, finally resolving all contradictions. -

Speculations in Idealism

You are confusing idealism with anti-realism. They are not the same thing. There is an entire subset of idealism called "objective idealism," that accepts the reality of external objects. This is probably the largest subset of idealism actually. Objective idealism doesn't deny that diseases exists, so there is no problem here. The key German Idealists were very into the science of their day actually. What they rejected was the claim that matter was ontologically basic and represents discrete "things in themselves."

Mental/physical is a false dichotomy in their opinion. Only subjective idealism is the claim that "everything is mental," in the sense most people would take that claim. The better way to think of objective/Absolute idealism is the claim that: "the subjective and objective are part of a unified whole." One cannot be understood except in reference to the other. This is also not dualism, it is a monism; we have different emerging from one thing, but two things.

Schelling wrote a lot. What I have from my notes is:

"

1. Ego is the highest potency of the powers of Nature.

2. Nature is the source of creative intelligence.

3. Reason is able to abstract from the subjectivity of the ego to reach the point of pure subject/object identity.

Nature is actually the self in disguise. After all, all of nature is only experienced through the self. But the self necessarily posits that which it is not, thus we get nature (Schelling following Fichte here). Schelling departs from Fichte in not having the self at the center of everything. Instead, the claim is that nature and the self represent natural dualities, and the whole of the entirety of being (the Absolute) is an outgrowth of/resultant from these contradictions.

The fulfilment of nature is to become object to itself (here we can see the influence on Hegel)." My handwriting is pretty bad, but I think that's what I came away with.

This seems pretty foreign now-a-days, but actually the claim isn't too far off from those many modern philosophers and scientists make when they claim that talking about various phenomena from "the view from nowhere," or the "God's eye view," is misleading at best, meaningless at worst. Objects and entities only exist in the mind. Empiricism is necessarily the study of how experience is. The positing of a discrete, ontologically basic world that fits the models we deduce from experience is a profound overreach and mistake.

What the older idealists add, which is now less of a focus, is an ontological argument about the nature of being. That the differences in being we experience are logically necessitated by the fact that there is something rather than nothing.

That and they tend to start by focusing on the self for building up their arguments, which is less popular today. But I think when you get rid of all the strange terminology and vivid metaphors, 19th century idealism's core arguments aren't that far from modern versions, they are just couched in very different language. -

What happened before the Big Bang?

It seems indeterminate. One way a professor recommended us to think of relativity is with distance as an X axis and time as a Y axis. You can move "faster" through one, but only by reducing your value on the other axis. At the maximum far end of the distance axis is the speed of light. Photons move the maximum amount through space and do not experience time at all. From the perspective of the photon, photons move instantly between interactions*.

With a black hole, the amount of information that is stored in one point in space exceeds the maximum possible without the creation of a black hole. Gravity warps space-time to such an extent that light can no longer escape. You appear to get a singularity and the destruction of said information.

However there is a lot of resistance to this arbitrary destruction of information in black holes, and an opposing concept has been advanced, that of black hole complementarity. The idea here is that all information going into the black hole is radiated (very slowly) back into space AND still goes through the event horizon, into the black hole.

This would seem to duplicate information and violate the no-cloning theorem, right? Potentially, but not so if no observers can ever see both versions of the information. Enter a (perhaps ad hoc) wall of fire that burns up observers at the event horizon so that they can not observe violations of the laws of physics.

We base our current concept of time on:

1. The direction of the trend from low entropy to high entropy.

2. The number of predictable cycles of a phenomena completed.

Our observers inside the black hole's sense of time will be dependent on if all black holes result in low entropy initial conditions for the universes they spawn and if the laws of physics work the same way for the new universes. If these two hold, the observers should have a time that is quite similar to our own. However, it still might be quite impossible to do an apples to apples comparison of the two times if no observers can see both universes. Comparisons would be fairly meaningless.

But that wouldn't mean that "nothing comes before the Big Bang," even if the Big Bang was the result of a black hole in a larger universe. If that premise finds support it would mean our concept of time is parochial and needs expansion. And for myriad other reasons plenty of physicists have already come out and said there appear to be deep problems with our current space-time and that it may need to be overthrown. Like I said in my other post, plenty of now foundational discoveries in physics have previously been written off as "meaningless" or worse still "metaphysics," so our ability to conceive of such changes now doesn't mean that much.

(*Even this example is somewhat fraught because we know that it's probably incorrect to talk about photon X moving between Y and Z interactions as if photon X has its own identity and we also know the photon itself only exists under specific circumstances of interaction, with a light wave existing otherwise.) -

Basic Questions for any KantiansI think a large amount of disagreement on the aforementioned topic comes from the misunderstanding that saying "reality may be radically unlike perception," is the same as saying "no information about the noumenal makes it to perception." The latter totally undermines empiricism, the former does not.

The crux of the issue is unchallenged assumptions about the way the world is that arise as part of our fundemental nature (some analogy to Kant's categories can be made here). But we may find that these categories are not absolute, but rather the products of natural selection, in which case the Fitness vs. Truth theorem dictates that these categories are vanishingly unlikely to correspond to things in reality.

But we don't see this view in much of science. Mainstream models of how vision works assume sight is essentially processing "what photons bouncing of surfaces is like," at some fundemental level that corresponds to a "view from nowhere." Ironically, we seem less committed to our sense of smell. We don't seem overly committed to the idea that cooked meat or freshly cut grass has a smell that exists outside of our perceiving it. But sight is more closely aligned with our model of 3D space, and we very much do tend to assume that objects in space like the Moon do exist within this space when no one is looking. The question is: is talking about the location of the Moon "in space" when no one is watching as silly talking about the smell of Mars when no one is around to sniff it.

Had we evolved with olfactory and visual faculties closer to flies (who apparently don't see surfaces), we might have a very different physics. Perhaps a physics that handles distances better but has a hard time dispelling the idea that fundemental particles must have an essential odor. "The quark is a fundementaly mathematical entity, we need to stop modeling it based around concepts of aroma," might then show up in theoretical papers. -

What happened before the Big Bang?

The physicists who developed the interpretations of QM certainly didn't see their work as philosophy of science. There is a vast number of discoveries in physics that were thought up long before there was a means to test them. Indeed, some were thought up when it was believed it was impossible to test the theories, that the new particles dreamed up would be necessarily unobservable. And now these are part of the bedrock of physics.

Point being, falsifiability is a poor criteria for what makes science "science." The "presuppositions and implications," of science often end up being important, and trying to kick them out to philosophy is a fool's errand. You don't end up with a science free of such theorizing, you end up with implicit theorizing that clouds judgement and cuts down on new ideas while remaining unexamined in the background.

Some interpretations of QM have led to testable hypotheses (versions objective collapse). Other versions may be testable in the near future.

Trying to draw a hard line between what is science and what is philosophy spawned Copenhagen and what you got wasn't actually science separate from philosophy, but instead science taking on unexamined elements of logical positivism that have stuck around long after positivism died. Given the history of the field in the 20th century, where talking about so many things that turned out to be of scientific interest was handwaved away as "meaningless," I wouldn't be so dismissive about theorizing about events "before" the Big Bang.

Bell was on the short list for a Nobel Prize in physics at the time of his untimely death for work in an area that has previously been described as meaningless. Now his work is central to applied science re: quantum encryption (already in limited use) and quantum computing (in R&D and picking up speed). Mach rejected atoms as meaningless because it was thought that observing them was impossible, etc.

https://aeon.co/essays/a-fetish-for-falsification-and-observation-holds-back-science

Not on an intimate level, well enough I suppose. In terms of plausibility, I think it is more plausible than it seems at first glance.

Imagine we do not find a good way to use observations to determine whether the Big Bang is unique or if it is just the inside view of a black hole (it's debatable if we're currently in this situation, but let's just assume it for now). What then is more likely? That the start of our universe was something wholly unique, or that it is the result of a phenomena that we now know is incredibly common?

There is no good answer there because there is no good metric for comparison. I think it just points out how, if you have two theories that might explain your data, you often default to the one that's been around longer, even if the new one might be more plausible on a common sense basis (allowing that common sense is normally bad grounds for science). Old paradigms tend to stick around by being first, not necessarily the most coherent.

But of course there is a difference as respects the question in the OP. If the Big Bang was a black hole then it might make plenty of sense to talk of time before the Big Bang. It could conceivably be a common textbook fact that we talk of something casually prior to that event, it just depends on what we find and how we come to think of it. -

Basic Questions for any Kantians

The lack of ability to visualize these things does not seem to be holding us back.

It doesn't? I won't pretend to be an expert on these things, but I've read enough histories of physics and recent books by physicists to know that problems with our replacement for Newtonian absolute space and time began to show strains almost as soon as it replaced to former paradigm. The idea that we are stuck and need a conceptual transformation to move forward seems quite common in the field.

Polls of of physicists show not a single interpretation of quantum mechanics has majority support among practicing physicists. The theory with the most support, Copenhagen, is considered incoherent non-sense by most of the physicists who more closely study quantum foundations. That seems like a pretty serious problem.

Despite plenty of evidence that Copenhagen is incoherent and that quantum events don't stop occurring at arbitrary scales, we still have deep problems with projecting our inherited world view onto the world. E.g. the double slit experiment being done with large macro molecules, entanglement involving 15 trillion + atoms, macroscopic drumheads being entangled, quantum activity being involved in photosynthesis and other biological phenomena formerly marked off as safely classical, non-locality (supposedly not violating the speed of light only because a suspect definition of information has been inserted into relativity as an ad hoc fix), observed FTL propagation in quantum tunneling, observed instances of violations of the conservation of energy, etc.

Indeed, sets of experiments using photons to test a modified version of the Wigner's Friend thought experiment seem to suggest that the entire idea of a publicly available objective truth is suspect. Our world of discrete objects and systems that exhibit haecceity seems like it might just be a trick of data compression and heuristics selected for by evolution without veracity in mind. The apparent truth we experience would then be merely the result of probabilistic trends, our science a profound set of misconceptions that nonetheless gets enough right to have idealized laws that allow for useful estimations. Which is of course, something that has proved true before. A core assumption of Newton's Laws is that matter is conserved. We know this to be a false assumption at the very core of the paradigm, but it still gets enough right to be useful; the issue then becomes mistaking useful for true (a problem evolution also seems to have in shaping perception).

In his book "The Lightness of Being" Frank Wilczek talks about how many profound discoveries in physics have resulted from taking known formulas that describe phenomena and restating them in various ways in order to think about them differently. In these cases the big discovery is not the discovery of a new pattern in nature, it's taking a pattern we've known about, in some cases for a very long time, and flipping it in ways that cut against our intuition, but nonetheless end up giving us new insights.

I think this is what Hoffman is getting at. If we don't take into account the fact that the world "out there" is very different from the world we experience, and don't allow for the fact that our models are selected for based on how well they fit our intuitions, which themselves were not selected for on the basis of accuracy, we risk getting stuck.

Science arbitrarily cutting chunks of being into "systems," is a good example here. We talk of neurons giving rise to minds often without much more than a footnote explaining "well yes, brains actually do no thinking without a body, which has an amazing amount of influence on cognition through the endocrine system and other mechanisms, neurons don't create a mind without the myriad poorly understood activities of glial cells (The Other Brain is a good book on this), and brains also don't create minds without interactions with the enviornment." But since the phenomena we care about doesn't exist without these other factors, they seem like poor exclusions. The discrete objects/systems schema we inherited, which finds little support in science, remains ubiquitous. Even more ubiquitous is the idea that "the laws of physics," are these rock solid descriptions of how the world "out there," works. They aren't, and we know this. They're idealized models we find easy to work with because of the inherited nature of how our minds work. Add a third body into our models of gravity and they fall apart.

Or, to sum up: he problem being diagnosed is that we appear to have a significant problem of mistaking a map tailored to the way our minds work for the territory itself. As Hoffman would put it, "the Moon isn't there when no one looks because the Moon is essentially a desktop icon on the screen of perception." -

Basic Questions for any Kantians

Hoffman's impetus for his book was the idea that our perceptions of "how the world is' are what may be holding us back in science. If we assume the world we experience closely resembles the world that actually is, chances are (at least if you buy the research he cites) that we're wrong, possibly at a very fundemental level. Evolution has left us with a perceptual and conceptual tool kit entirely at odds with the goals of science.

We already see this with how difficult it is for us to wrap our minds around the way very large and very small things work. So it might be that to take the next step we need to challenge even more deeply engrained ideas, for example, the idea of discrete objects and systems, the idea of linear cause and effect, the idea of three dimensions + time representing a faithful interpretation of how the world is.

I don't think these ideas get you off into the territory of unanswerable metaphysical questions; they're still very much in the realm of questions science attempts to answer. The world we see in physics, with non-locality, informational content corresponding to 2D surface area, not volume, complimentarity, the creation of mass, etc. suggests he's on the right track. -

Basic Questions for any Kantians

Yeah, bit of a red herring on my part. I mentioned the Phenomenology only because it's a good work arguing against radical skepticism. I see the two things (moving past radical skepticism and adopting realism) as somewhat related in that I don't think there is a way to resolve all objections to them completely to anyone's satisfaction based on logic alone. Decarte's Demon could always be feeding you any evidence you think you get from experience, there is no way to rule that out (or to totally rule out Hume's arguments against induction, same sort of issue), but there are obviously benefits to moving on from that place of skepticism.

I thought it was unconvincing because the explanation of how there can be multiple minds within a larger, universe sized-mind seemed fairly ad hoc. He uses disassociative disorders and multiple personality disorders as the model for his explanation and there just doesn't seem to be any reason to think this big ontologically basic mind would reflect these disorders.

Then he has living things as being the possessors of these disassociated minds. He then claims that AI will never be minded because minds are unique to things that are alive. But the line between living and nonliving is not clearly defined today, so this seems fairly fuzzy at best, open to an argument along the lines of Hemple's Dilemma at worst.

These two parts seemed quite ad hoc to me.

Edit: I should note, this was "The Idea of the World," I haven't read his others. -

Fitch's "paradox" of knowability

Ironically, this is relevant given empiricism tells us that knowing a quantum object's velocity makes its position unknowable and vice versa. Another point for unknowable truths. It's all quantum! (...you brought this on yourself). -

Basic Questions for any Kantians

I'll have to check it out. Seems like similar conclusions to Hoffman's as far as the noumenal world is concerned, at least in that the reality of the 'view from nowhere' would be an objectless world, quite indescribable to us. One of the more interesting theories Hoffman had was that elements of how we perceive three dimensional space might be an artifact of an error correcting code used in perception. This might explain how we have observations supporting the Holographic Principal, but don't experience a two dimensional world, or at least it explains it more plausibly than some of the other ones I've heard.

I do think his arguments on how evolution shaped perception do a good job explaining why we insist on thinking about very small things as just paired down versions of the sorts of "medium sized objects" we have around us. We have evidence that some of our "deepest" measures of physical reality are subjective at heart (e.g., entropy re: the Gibbs Paradox), and this subjectivity flows from thinking about small objects as just being shrunk down large objects. For example, if haecceity is simply a property of the statistical tendency of very large collections of small things not to become completely indistinguishable from one another, then a great deal of how we measure potential microstates, the use of extensive formulas, is arbitrary and the result of how we evolved to deal with very large collections of "stuff," not how that stuff actually appears to work at the scales we are investigating. So, we also get non-extensive forms of entropy, Tsallis entropy, etc. and end up with situations where entropy is different if we know we have mixed two different gases than it is if we do not know this fact (i.e. subjective). But this seems like a problem when we are defining time using this same measure.

The main analogy used in Against Reality is that of a computer desktop screen. On a desktop, you see icons representing a trashcan you can drag files into. You rearrange files in folders. All this is completely unlike how the changes are actually processed within the computer, as adjustments of microscopic logic gates. We experience an email dragged into a trash can. We can also pull the email back out of the can. In reality, all that goes on is a very large number of changes in a few different types of logic gates relative to others. The idea is that our senses similarly provide us with a useful "desktop" interface. The "real world" might be as far from our sensory models as the electrical activity of a microprocessor is from dropping one file into another. In which case, a lot of our deep scientific problems might stem from the projection of the logic of our "desktop interfaces," into the world.

For Hoffman it is ludicrous to talk of "neurons giving rise to minds," as such because "neurons" only exist in the minds of human beings. Our idea of neurons might have some relation to the noumenal, but it is by no means very direct.

Having read Becker's What is Real? on quantum foundations just before The Case Against Reality, I found this to be more reasonable than I might have before. After all, we have this huge issue of an arbitrary classical/quantum divide hanging over our sciences that seems less and less supportable. We also have all sorts of holes that have emerged in the conventional model of relativistic space-time, such that space-time looks to be in similar shape to Newtonian space and time circa the later 19th century (i.e. ready for replacement).

We know our laws are just gross approximations. Newton's Laws don't actually describe how physics works, they describe an idealized system with only two bodies, where those bodies do not have composite parts and are in isolation. The issue is that we mistake predictive power and usefulness for veracity, which is falling into the very same trick as when we assume our senses must report the world "as it is," because they are useful. But selection for usefulness is a different criteria than selection for truth.

Indeed, in Deacon's Steps to A Science of Biosemiotics its pointed out that life has to filter out truth, as actual representations of the truth would entail bringing in so much entropy into the organism that it would dissolve.

My own personal view is that the 'view from nowhere" or "God's eye view" is a sort of demon haunting the sciences. It makes no sense in the context of our physics. Things only have and exchange information in relation to other things. We need descriptions that have this baked into the cake. A thing is what it is for something else. Fichte was totally right to write off the "thing in itself," as nonsense.

We also need to recognize that, within a single phenomena we want to examine, a thing might fit into any of the three points of a semiotic triangle. Vision might have the object seen as the referent, the patterns of photoreceptor activation sent down the optic nerve as symbol, and the brain as interpretant. But within the context of the entire phenomena it may be that a pattern of neuronal activation in one region of the brain is the referent, the symbol is another pattern of activation within neurons connecting the referent area to another processing area, and the interpretant is this new processing area, which may itself be a symbol or referent in another set of parallel relationships. These relationships, and the definition of systems themselves, are necessarily arbitrary subjective abstractions. That's fine, it turns out entropy is too. It will still pay to have a way to formalize these subjective relationships somehow.

Information, when defined as the "difference that makes a difference," changes in context. Objects that may be synonyms in one type of relationship might be distinct in another.

I feel like this is sort of inevitable. You have to assume the noumenal exists from the outset. Otherwise you can always just see science as a description of how mental objects interact. You can't fully exorcise radical skepticism, but plenty of good works have been done to talk people down off the ledge of skepticism (the Phenomenology of Spirit being the example I always look to).

Kastrupt's Idea of the World, while advancing a less than convincing idealist ontology, has a very succinct overview of the seemingly intractable problems facing realism and particularly physicalism. But the interesting thing to me is that the same arguments he uses can be easily flipped around to show how, assuming that physicalism is true, we would still have these same intractable issues anyhow.

Science will always have a problem explaining the characteristics of subjective experience because you're asking a set of abstractions that exist as a subset of the world of experience to explain all of experience. Its asking something ontologically derivative to explain its ontological primitive. However, it would seem to hold that this would be a problem even if physicalism were the case, so in a way it's a helpful explanation of physicslism's apparent failings and only damaging to certain formulations of naive realism.

This seems like a real benefit. Parts of the Hard Problem can be chalked up to the same sorts of epistemological issues that keep solipsism and radical skepticism viable. This I find far more convincing than arguments that try to tell you that experience isn't actually real to deal with the issue, which always seemed like a giant bait and switch to me. -

Basic Questions for any Kantians

I read Hoffman's book recently. It's pretty good. I was a little disappointed that it didn't go into any of the research on the way information about the noumenal makes it into the mind. Information theoretic approaches cover this quite well IMO, even if they can't solve the hard problem, so it seemed like a bit of a hole. -

What happened before the Big Bang?

You don't need to jettison the standard model to have different cosmologies. You need the Big Bang to understand the directionality of time and explain why the universe had lower entropy in the past.

The standard model is reversible, so without the Big Bang you'd just have a block universe where any "slice" representing a given moment is arbitrary.

This is a possibility that has been floated. Particularly as part of the myriad variations of string/M theory. These parallel universes would have different laws of physics.

In the case of this thread, I think "before" the Big Bang should be interpreted as "causaly prior to." Interestingly, there are models that limit themselves to just our universe that propose that the future (as we see it) may be casually prior to our present. The future "crystallizes" into the past, and the present is what this crystallization looks like. This is the crystallizing block universe.

There is also the idea that the Big Bang is the result of a supermassive black hole. We are on the inside of that black hole. Black holes in our universe would represent "baby universes" of our own universe. Pretty neat.

Unfortunately, like competing interpretations of quantum mechanics, while the theory fits observations, there is, as of yet, no predictions we could explore to differentiate between the Big Bang being our inside view of the formation of a massive black hole or it being unique. -

US politics

The Supreme Court could allow states to re-implement abortion bans because it was a court decision that originally made it illegal to have bans of abortion.

If Congress had ever passed a bill making abortion illegal they couldn't do this. Basically, it was a right ensured by a court decision.

Now the Court could also have said a law ensuring the right to an abortion is unconstitutional, but that would face a much higher bar, and no such law existed.

As to the question of deadlock, its in large part due to two factors:

1. Representation in the Senate isn't based around population but around the arbitrary borders of US states. This means that some citizens have outsized representation relative to others and so widely unpopular actions can still have a majority of legislator's support.

2. In general we do elections as "whoever gets the most voters wins." Some states have runoffs, most don't. Very few states do ranked choice voting or instant run off voting. The way party candidates are selected for races is in party elections called "primaries." These are often closed elections where only party members can vote. They also have low turn out. Generally, older and more radical people are more likely to vote in the primaries.

The result is that third parties are generally not competitive and that the candidates from the two major parties tend to be far more radical than the median voter. So most voters being unhappy is sort of baked into the process as the winner of elections is often going to be the person who has the most support from their party's more radical elements. This isn't always the case, but it often is.

Any attempts to fix these problems is resisted by the people with the power to change how elections are held because they are less likely to stay in power if elections are changed to make the preferences of the median voter more likely to be reflected. -

Fitch's "paradox" of knowability

But this would only apply to a small subset of unknown truths, those that follow the form "no one knows that X" where X is a true proposition.

And while this set of truths cannot be known, the past tense version "no one knew that X was true," can be known. I don't see this as a huge problem.

Indeed, I'm not even sure if this problem holds for an eternalists view of time in the first place. If all moments in time are real, then the issue is simply that the knowledge of the truth of the "known one knows that X is true" proposition has to occur simultaneously with the discovery of X being true. But the addition of a past tense would really just be an artifact of our languages' inability to transcend the present. . After all, if the past is real then there is a reality where "no one knows that X is true" is still true and someone in the future can have knowledge of this past truth. If this holds, the truthmaker of the the fact that "no one knows that X is true," still exists even after someone knows X.

This doesn't seem too dicey to me. There are plenty of good empirical reasons to accept eternalism (e.g., physics) -

Time Entropy - A New Way to Look at Information/PhysicsInteresting. Enformy seems like it would be an emergent factor from:

The laws of physics being what they are and allowing for complexity to emerge.

The universe starting in a low entropy state due to conditions during/preceding/shortly after the Big Bang (The Past Hypothesis)

The fact that this tendency from a low entropy past to a high entropy future creates natural selection effects on far from equilibrium physical systems.

The fact that the mathematics/physics of self-organizing / self-replicating systems works the way it does and synch can occur in disorganized, chaotic systems.

The fact that information about the environment confers adaptive advantage on a replicating system.

The fact that fundemental information in the universe can be encoded at higher and higher levels of emergence in a sort of fractal self-similarity.

---

On an unrelated note, I'm realizing now that this measure of entropy is sort of dumb for any finite, closed system. Poincaré recurrence theorem dictates that every potential state of an isolated/closed system will be a past state of that system at some point, given a long enough time.

I was unaware of the Gibbs Paradox and came up with the same problem myself but the folks at the Stackexchange physics section helped me out. I was not aware that there were multiple entropy formulas or that the measure is somewhat subjective. I feel like every subject is an onion with no bottom. -

Is there an external material world ?

I've seen a few main approaches:

1. Propositions are abstract entities like universals. They are mind independent in the same way that spheres and squares don't require a mind to be defined or to have properties that are true or false of them.

2. Propositions are linguistic constructs and not mind independent. (This is somewhat less popular because it seems to entail statements like "the moon exists" aren't true or false outside the context of communications or beliefs).

3. Propositions are the main ontological primitive of reality, i.e., all of reality can be compressed and encoded into true/false statements. Essentially this is just #1, except that this goes a step further in saying that other abstract objects end up being derived from propositions. The case for this is that you could encode everything that's going on in a physical event, say when one pool ball hits another, in binary.

I've noticed a tension between 1 and 2 in that often the people who want to deny that abstract objects are mind-indendent tend to also be the people who want to claim that the truth or falsity of propositions is, in at least some cases, mind-indendent. I do not know of a good way to resolve this myself. Perhaps propositions can be merely metalinguistic constructs, but the truth of a thing is a property the thing itself, or a property emerging from a thing and its interactions with another thing (i.e. information transfer). I'd like a theory like that but I don't know of one that holds up.

For some reason, propositions existing as abstract objects independent of minds never bothered me as much as universals doing the same. -

What's your ontology?Full Absolute Idealism! Not only is the Law of Non-Contradiction violated, it is these very violations that result in the world of becoming we experience. We live propelled through life by the logical explosive power of the excluded middle we inhabit.

:cool: -

Fitch's "paradox" of knowability

Correct me if I'm wrong, but doesn't this only hold if you take as a premise that "all truths are knowable." The issue is the existence of an unknown truth that cannot be known, as its being known entails it no longer being true.

But if you accept that there are unknowable truths then you're not in any difficulty. So, this seems to me like a potentially major problem for verificationalism or versions of epistemology where truth is actually about attitudes and beliefs (but not all of such systems, I think Bayesian systems escape unscathed), yet not much of a problem for other systems.

I am honestly flummoxed by SEP's list of systems that would be imperiled by this. Berkley seems like he can get out of this easily due to the fact that the unperceived truth of p doesn't exist, and anyhow God definitionally knows all truths for him already. Peirce’s system is also an odd one on the list. The "end of inquiry" would presumably be once we know the truth of p's referent, and so the paradox of one truth passing away as another is recognized is just part of the pragmatic process of gaining knowledge. I'm not even sure logical positivism is hit that hard. After all, it was the basis for the Copenhagen Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, which very much supposed unknowable truths. The conclusion was simply that statements about the true absolute position/velocity of a particle were meaningless. Copenhagen is generally criticized for being incoherent, but this is because it creates a totally arbitrary boundary between quantum systems and classical ones not because it discounts statements about unmeasurable values. -

Education Professionals please ReplyProbably not. I've only worked managing school districts as part of cities I've managed or districts I've consulted for, so I don't know much about the pedagogy here. That said, if you look at the cognitive science research on how learning occurs, it appears that context and the ability to assimilate new knowledge into an existing web of context is crucially important. There is a good book called "The Knowledge Gap," that goes into this.

Already, it seems like we spend too much time drilling kids on skills in order to improve their test scores and not enough time on content. The thing is, research suggests content context is essential for building up skills.

I went to a very poorly performing school district that would lose 75-80% of students before graduation. I was pretty terrible at math. It seemed like nothing more than a vague set of arbitrary abstractions, useful for nothing but passing tests. My big question "why is the order of operations what it is?" was met with "because you will get a wrong answer on the test otherwise."

I did fine in math in college now that it was tied to content and I understood use cases and had a quant heavy course load in graduate school, success in a quant heavy field, taught myself several programming languages, etc. The reason I couldn't hit the low bar for expectations in 10th grade math, and probably why hardly anyone else could, is because it was divorced from anything interesting.

Now I love math. It's philosophically extremely interesting. Formal logic could very easily go the same way. We should instead be doing a lot of content, with a focus on debate and critical thinking. We should teach science as it actually works, as an imperfect process of exploration and testing, not as a long list of facts. We should go over how we know what we know, and why some people think we don't know what others think we do (you could do the Hard Problem with middle schoolers if you simplify it enough). This is where all the meat is; put the critical thinking into tangible questions about life everyone has.