Comments

-

The problem with "Materialism"

Oh, gotcha. That seems like the same thing though. The flip side of a perfect Chinese Room is that you ask all the questions in your language. So whether it "knows" what it is hearing, or not, it can generate a response, and if it is good enough, no observer could tell the difference. I'm not sure how this would be different. -

A "Time" Problem for Theism

If you don't mind archaic translations, esoterica, references to symbolic systems like Alchemy or Hermeticism, and mystic allegory, you might appreciate this:

It deals with a similar topic. Boehme was quite influential, in Christian theosophy and in philosophy, particularly through Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel. Whitehead has some Behemist influence too.

I will caution though that it's fairly arcane. In some ways, it's a lot more intuitive than Hegel, but in others it requires more flexibility.

The basic takeaway is that we know there is being (becoming) because we're here. So how did God have being before creation, before time?

Behemism says God couldn't have being in that period. Genesis starts with "In the beginning," a begining that coincided with creation for a reason. Because if there is only one thing, God, how can God have any meaning. An infinite string of ones carries no information in the same way an infinite string of zeros lacks information. As Sausser says, "a one word language is impossible," because if one word carries equal reference to all things, it denotes nothing.

In Boehme, this means God's knowledge of God is frustrated. God cannot define God. God must posit another, must create, in order to be defined, hence creation and time.

Hegel builds up a similar story, starting with a thought experiment on human experience. Pure sense certainty has no definiteness. You don't see dogs or sheep or trees. There is only a now, devoid of interpretation. But this pure, undefined sensory stream lacks all meaning, and so is itself pure abstraction. This pure being is contradicted by the pure nothing of its content. The contradiction results in being sublating nothing and incorporating it into itself. The result is becoming. We experience a now of being that falls away continually into nothing. The new concept entails both, the beingness of being in "now" and the nothing of nothing in the falling away of "now," which is then replaced by another "now" of being.

Our Newtonian heritage has us think of space and time as a receptacle or container for things. However, the time and space we find in relativity is dynamic, and time and space are relative. Whitehead envisioned spacetime as a relationship between processes, point events, rather than a container.

Talking about time before creation, when all being was God, is then misunderstanding the term. It's akin to Zeno's paradox. If space and time are infinitely divisible, how can Achilles ever pass a tortoise? Every time he closes the distance by half, there is always another half to go.

Mathematical solutions to this were always lacking. Physics eventually solved the problem though. Velocity is a relationship between entities. It is itself a measure of distance / time, but one that is necissarily relative between points of observation. A coffee mug "at rest" on my table is actually rotating on the Earth's axis at a tremendous speed. It is also moving relative to the sun through space, and the sun is moving relative to the center of the Milky Way. Speaking of absolute time, relative to nothing is a Newtonian holdover. You'd as well ask "where was space before creation."

The problem here is one of applying an abstraction that is necissarily relational to a non-relationship.

To go back to the communications example, God then is not like an infinite stream of ones. God is like a waveform of infinite amplitude and frequency. As frequency approached the infinite, the peaks and troughs become infinitely close together, canceling each other. The result would be silence, but not an empty silence. The wave would contain a pleroma of information, the entirety of all possible functions. It can, however, only be heard through a reduction of its amplitude and frequency. Negativity, reduction, differentness, become requirements of being. -

The problem with "Materialism"

That koan is singularly innappropriate, given the context.

I know, that's why I like it so much. It's a perfect inversion.:grin: Being a moist robot IS the real enlightenment for the eliminativist.

begs the question

I wasn't trying to. I mentioned people in the context of other objects because I meant "people insomuch as they are objects," but phrases like that give precision at the cost of bloat. The point wasn't that people are necissarily physical, moreso that if a dad tells their kid, "go ask mom," the child's prephilosophical command on language gives them no trouble looking for the physical room in which their mom is located.

...none of that negates the kinds of philosophical problems that, for instance, Immanuel Kant set out to solve. In fact there's voluminous literature on Kant's contribution to cognitive science, and Bishop Berkeley wrote a treatise on optics. Schopenhauer also was keenly interested in the science of his day, and saw no conflict between it and his idealist metaphysics.

Such as? I think I agree though. There are practicing dualist neuroscientists, physicists who appear to embrace some flavor of idealism, etc. I don't think your ontological leanings result in any necissary barrier to contributing to science or philosophy, especially if you're willing to consider evidence for opposing views in stride. This is why I said I haven't seen versions of "epistemological physicalism," that appear necissarily "physicalist."

Rather, coherence demands a good reason for accepting ideas that overturn fundemental scientific findings, so what we might call "non-physical causes" tend to have a higher bar to pass, but only insomuch as they violate coherence and result in scrapping tested laws. Physicalism itself is protean, and every researcher who dreams of being a paradigm shifter is essentially hoping to redefine physicalism, perhaps in ways such that it is no longer recognizable.

This gets at the other problem I mentioned, physicalism becoming vacuous. Because if something we considered dualism now turned out to be observable, replicable, and predictable, it seems that it would be incorporated into physicalism.

not just the fortuitous byproducts of a blind watchmaker

I think this is an unfortunate holdover of old school physics. It's distinctly Newtonian. The "clockwork universe," is why physics abandoned classical scale problems for most of a century, and could stick its head in the sand vis-á-vis problems like the inability to do simple things like predict a pendulum's swing, or meaningfully predict the weather. The "chaos revolution," hit academia hard, but left popular notions fairly unchallenged. QM was taken as simply replacing a deterministic clockwork with a stochastic one.

The clockwork model also seems to blind people to the possibilities of top down causality through various levels of emergence. However, when the forces that drove the emergence of human minds result in humans building giant particle accelerators, and bringing forth esoteric particles that do not appear to have existed since the very earliest moments of the universe, it certainly seems to me like top down causality is a thing.

First, the term 'intentionality' as I was intending it, and as it is used in phenomenology, refers to the fact that language, at least a good part of it, is about things. I was not intending to use the term in it's "normal" usage as referring to having intentions.

Second, given the sense of 'intentionality' I was using, whether or not the speaker or author has any intentions regarding what the language they are using is about, the language use is, in itself, about whatever it is about (although of course a recipient competent enough in the given language to be able to understand what it is about is required).

And third, even if computers are able to fool us, that is only on account of the fact that we have created and programmed them well enough to be able to achieve that feat of deceit

Seems I misunderstood. However, I think the same sort of objections would apply on the physicalists' side. You seem to be saying that the Hard Problem has to be solved to account for language, because language use is somehow not fully realized if it isn't being used by conciousness. It can't just have a referent (e.g., a bot selecting specific rows of a SQL database based on a natural language question), it needs some sort of sentient "aboutness" attached to it. I think plenty of people will disagree with that premise.

If you have an ideal Chinese Room, and its behavior, the use of language, is always undistinguishable for any observer, regardless of if the Room has intentionality about the objects of language or not (is a sentient AI versus a bot), what then is the difference? Even from an idealist perspective, I'm not sure there is one that it is possible for us to demonstrate.

Because if all observers see the same thing, regardless of intentionality, then two phenomena share all their traits, and if the Chinese Room is perfect at mimicking language behavior, then the traits of X (the Room) necissarily are the observable traits of Y (the intentional speaker), but then these share an identity and are actually the same thing.

Now I suppose that the argument is that the difference is that in one, our intentional speaker is themselves an observer, whereas in the other there is no observation point. However, the two seem indistinguishable for all other observers, so it is an unsolveable problem. To my mind, this is more indictive of idealism's problems with solipsism than it is a problem for physicalism. Unless idealists have a good method for explaining how to distinguish sentences with intentionality from those without it, they appear in a bind.

Although I suppose idealists could just claim that a Chinese Room can't actually perfectly mimick language behavior. But this counter argument has to rely on claiming that perfect language behavior as seen by other observers is impossible (an increasingly harder bar to meet as AI gets better), because if the claim is that the two aren't the same because one has intentionality and the other doesn't, then their argument is reduced to a tautology and doesn't seem as strong.

Not to mention, many physicalists, particularly non-reductive ones, accept predicate dualism. They fully accept that the physical sciences cannot describe subjective experience qua subjectivity. So what they are really concerned in with when defending physicalism is how non-physical forces can account for things like physical brain damage destroying language capabilities. I have generally not seen good dualist responses to these issues. That people who have recovered from large strokes also describe their subjective experiences being totally dislocated by a physical injury, is also a blow against claims that conciousness only requires the body for physical action. Brain injures and the effects of psychoactive drugs seem to tell us that physical changes in our bodies can absolutely effect our subjective experiences.

Edit: On second thought, I don't even think my own language has intentionality in many cases. When I get stuck on a philosophical question and then my wife starts talking to me about home decor, which is really not my thing, I definitely say words and agree to things like spending a whole day trying to recenter shelves on a wall in plaster, instead of using the studs, without realizing it. If my language had intention, I wouldn't have said that, because putting heavy stuff up in old New England plaster suuuucks, unless you enjoy ripping holes in your wall, and I would have know I was agreeing to do something like that. -

The problem with "Materialism"

But at the centre of those reactions, is interpretation - what the sentence means. Animals react to threats or other stimuli, but we alone interpret the meaning of words

I'm just not sure if I buy this. When I call my cats for dinner, they come running, whereas they will ignore me at other times. They appear to know which call means food. Pavlov's dog appears to have learned the referent that the bell was used as a symbol for.

I've taught my in law's dog a few commands too. They get that different verbal commands refer to different things.

This works at a smaller level too. The "alphabet" of DNA appears to function as a symbol. It has a clear referent, the proteins it is coding for, and an interpretant, the transcription RNA. -

The problem with "Materialism"

Sorry, I don't even feel confident explaining a theory of language production, let alone intentionality. I couldn't even give you a particularly good recommendation on the language side. All the work I've seen is very much in the early stages, with multiple competing hypotheses, and a lot of interesting experimental findings, but certainly not a holistic answer.

However, I would argue that the premise that intentionality is a prerequisite for language use seems pretty vulnerable. Why is that necissarily the case? The Chinese Room thought experiment illustrates a difference between comprehending and using language. One seems completely possible without the other.

AI chatbots, although still fairly weak, have come a long way in the last few years. The Microsoft Dataverse has made the technology available at a much lower price point and I expect that being able to ask questions about your data in natural language to an AI will be a standard feature of higher end business intelligence platforms within just a few years (meaning the public sector will get it sometime around 2080, or whenever their ancient Access based solutions stop being supported ).

A cheap Alexa under $200 can be asked to look up the score of a game, search for a recipe, let you know the weather, or recommend you a movie based on your specific tastes with verbal commands.

High end AI can do more impressive things. It can tell a story about a picture. You can feed it some text from a work of fiction and it will write a plausible continuation using the same style. It can trawl the web for facts related to some topic and write a blog post about it.

Now to be fair, while the stories are actually quite impressive, the AI blogs are usually shit for some reason. Knowing what is interesting about a topic appears to be much harder than aping an existing style. However, I have also received papers from undergraduates who also simply trawled the web and tried to say something interesting about a topic that were even worse than these AI efforts.

Plus, Watson stomped Ken Jennings and the other Jeopardy! champs like a decade ago.

So, if a computer generated chat bot can produce language well enough that it will fool most people, and if it can provide answers to questions that are better than those a call center employee generally would, a place we may arrive at in the medium term, it seems that either:

Computers have intentionality; or

Using language doesn't require intentionality.

Some people would argue intentionality doesn't even exist anyhow, but that's aside the point.

All that said, language doesn't seem like a huge problem. But for dualists? Why does intentionality and language use only show up in living things? Why does the most complex use of language show up in the living thing with the most complex nervous system? If a non-physical life force guides these things, why don't plants exhibit them? Why can't my pen, or a rock, or a cloud demonstrate them? If the phenomena aren't driven by physical forces, why should they only show up in things with a particular physical structure? There is also the whole issue of brain injuries to areas that see increased activity during language use destroying a person's ability to use language, or anesthetics knocking out the ability to use a non-physical ability.

There is the violation of Ockham's Razor on the one hand, since the new force being introduced doesn't seem to offer additional predictive power, and the inability to explain things physicalism can explain on the other.

If intentionality is a non-physical phenomena, it must at the least still be partly caused by physical things. But then you have the problem of how two totally different things interact, and how they can interact without leaving behind detectable evidence.

As to meaning: DNA has meaning, you can apply a semiotic triangle to it. However, do ribosomes exhibit intentionality?

Meaning (information) is one of the most interesting and fascinating parts of the physical world. Information theory has become one of the biggest influences in changing the sciences in the past decades, right up there with chaos and emergence, although maybe a decade or two behind in acceptance. It has created its own subfields in physics, economics, and biology.

I'm not convinced that the physical meaning of information theory, which finds instantiations of information down to the level of fundemental particles, is necessarily something entirely different from the meaning of language.

The Great Courses lectures (The Science of Information) on this are particularly good as an intro btw. Although if you get bored when it turns towards cryptography and error correction, you can probably skip ahead to information in biology, sports, and physics without being too lost. -

The problem with "Materialism"

It just seems hard to reconcile the brain's decisive causal priority with common medical problems, like defects in the pancreas resulting in a person behaving like they just slammed most of a fifth of vodka, or the role of the immune system is causing (versions of) schizophrenia. Anaphylaxis certainly seems to flow causally from the immune system, and since it can cause death, would represent about as large of a change in the brain as you can get. -

The problem with "Materialism"

Language is tricky because it's an extremely complex emergent phenomena, so it's not easy to describe what is going on with any great deal of certainty.

That said, it doesn't seem like a particularly tough case for physicalist models. We know that sensory organs record incoming information about the world. This information is then procesed and refined, so that it makes a coherent enough picture of the world that an animal can get by as respects fulfilling its biological needs. This information is also compressed and stored for use in various memory systems.

The flow of incoming information is ceaseless, and the amount of information in the world is huge, so a major task here is filtering the information to bring out the salient details (e.g., the human VC has special areas designated for recognizing faces) as well as error correction (e.g., papering over the blind spot where the optical nerve enters the eye). Even then, only a small amount of the information can be coded and stored for future use. This enters long term memory.

In order to compress this information, the full range of sensory data isn't recorded. When people are asked to remember details of past events, we see the same areas of the brain being used that are used to process new incoming data. An upside of the data compression here is that the computational power used for memory can also be used for projecting the future.

So, based on past events, we can envision future ones. This obviously has huge adaptive value, since an organism can use information about the environment it previously obtained to solve new problems. Since DNA is a mechanism for storing information about the enviornment, cognitive systems represent somewhat of fractal reoccurence of the same pattern at a higher level. Language might be another such occurrence.

Projecting the future isn't unique to humans. I'll often see my cats gauging the length of a jump they intend to make, trying to judge if they can stick the landing.

Language is a way to code information for retrieval. Language makes it easy to share information. It makes sense why it would provide adaptive advantages.

Deriving meaning from language is something that has to be learned. Children don't learn to speak or read if isolated from interaction. So it requires physical stimulus, which is a good indicator it is physical in nature. That damage to the language focused areas of human brains impedes or outright halts language production is another data point for a physical origin.

Language lets us abstract symbols from their referents. "The big yellow dog," doesn't need a referent, it can be drawn up from past experience. However, the information about referents certainly seems to be coming from external objects, because language is very good at referring to external physical objects. When you ask for the salt shaker, there isn't confusion about how your words can apply to a physical object.

Second, information in every form we've studied turns out to be physical. Physical information cannot be created or destroyed. If human language was somehow a violation of this principal, we should see something physically unique going on in humans as respects their energy output relative to intake (or maybe not if the meaning is non-physical).

However, if the meaning isn't physical, it seems hard to explain how it could refer to physical things so well, or how physical things like other people or dogs can meaningfully and consistently respond to language and find physical referents based on it.

Codes aren't unique to conciousness, so panpsychism shouldn't have a huge bearing here whether it exists or not. DNA codes for protein structures (and not a specific protein, but an abstract recipe for building myriad copies of a protein) but DNA isn't sentient. Self-replicating silicon crystals show a similar talent at a much lower level of complexity.

DNA is normally seen as a code that stores information about the enviornment. Sensory data is obviously quite similar. I'm not sure how language diverges meaningfully, except that its human users have the computational power and talent for identifying synonymity to also use language for all sorts of predictive and artistic functions too.

Language seems like a harder problem for dualists than physicalists to me, and not really that much harder for a physicalists than an idealist. -

The problem with "Materialism"

.The brain regulates it entirely. Nothing else to it. It beats because they brain tells it to.

I was responding to this. There are "other things to it." A diagram showing a one way arrow from the brain to the heart is not an accurate picture of how the circulatory system works. Note, I did not write "the brain does not control heart rate," I said "plenty of other factors outside the brain," work to control heart rate.

"Heart cells" beat without the brain is what I said, not "the heart beats without the brain." And it is neat, you can watch it on YouTube.

These are individual parts of the body, all of which is dependent on the regulation provided by the brain.

Correct. I didn't write anything to the contrary. It is, however, also true that the brain is an individual part of the body that is regulated by, and dependant on other parts of the body.

So for example, I said the ENS has a great deal of autonomy, not that it is autonomous. You shouldn't write off interest in the ENS as simply a series of wires for commands from the brain. It has helped us find out a lot about how the brain works and is an area neglected by neuroscience until more recently. -

The problem with "Materialism"

The brain regulates it entirely. Nothing else to it. It beats because they brain tells it to.

This is incorrect. Heart cells will beat in culture, disconnected from the body, and they synchronize their beats if they touch. The sinoatrial node is the main player in mediating heart rate, but plenty of other factors outside the brain play a role (hormones, consumption of exogenous chemicals, etc.).

A wide array of biological functions take place outside the direct intervention of the brain. You might be interested in the enteric nervous system, the "brain of the gut," which coordinates digestion without much connection to the rest of the nervous system.

Other parts of the body also shape conscious experience. The endocrine system plays a huge role in emotion, the regulation of wakefulness, satiety, feeling like you need to take a leak, etc. As someone whose wife is about 9 months pregnant, I'd say you ignore the role of hormones in cognition at your own peril!

The body also appears to play a direct role in qualia. Research on people with severed spinal cords shows that people experience anxiety in less unpleasant ways when they are not receiving feedback from their body. This makes sense intuitively when you think about how people describe extreme anxiety: "butterflies in my stomach," "a pit in my throat," etc. When the neuronal correlates of given emotions are part of feedback loops that involve the rest of the body, it doesn't make sense to speak of the emotion happening only in the brain.

There is, as a I mentioned earlier in this thread, a recurring type of article in neuroscience: the article bemoaning "crypto dualism." These authors argue that neuroscientists are doing a huge disservice to people when they use phrases like "your brain," in their papers. References to "a person's brain," is misleading they claim, because people are their brains.

This whole argument is wrong on two fronts. First, people aren't just their brains. They are the process of interaction between their brains, their bodies, and their environments. The truncation is artificial. Just as ignoring the body makes you lose part of the story, so too does ignoring the environment. In a person is the sum total of their experiences, thoughts, and actions, how can these be isolated from the environment? Nothing happens in a vacuum.

The problem becomes more acute when you look at it from the standpoint of adjacent fields. In social psychology, you have a core doctrine called "the fundamental attribution error." This is the tendency of people to over-emphasize explanations of behavior that rely on traits specific to the person acting (e.g., personality, genes, sex, etc.) instead of situational explanations of behavior.

What social psychology has generally found is that setting influences behavior to a large degree. Given the proper manipulation of the setting of an experiment, you can get all sorts of behaviors out of people. They will say a line that is clearly shorter than another is actually longer if enough other people have already verbally agreed that the short line is the longer of the two. You can get someone to turn around and face the corner of an elevator for no reason.

In these cases, the behavior, which is a core component of what a person is, gets driven by emergent social pressures. To be sure, things happening in the brain are involved in the behavior, but the behavior appears to be driven mostly by the situation. People who vary quite a bit in genetics, hormone levels, intelligence, etc., that is, people with a good deal of variance in the areas of the brain that drive behavior, nonetheless can be guided to behave in mostly identical ways with the right situational set up.

So, "you are your brain misses" that part, you are more than your brain. You are also less than your brain. "You are your brain" also misses that conscious awareness contains an order of magnitude less information than the brain. You have limited attention, and you have to direct your attention to get information into conscious awareness. The amount of information processed by the human brain is around 38 petaflops, 38,000 trillion operations per second. The amount of information in conscious awareness (harder to define or measure), is generally measured in mere bits, and not even very many bits. Short term memory is particularly lacking, with a storage capacity of 5-10 symbols.

The readers of articles "being their brains" has some difficulty with this. When you tell someone that their brain is doing X or Y, it certainly is the case that the parts of the person you're getting through to are not identical with their entire brain. -

Reality does not make mistakes and that is why we strive for meaning. A justification for Meaning.

Good advice. I'm used to forums that automatically quote replies.

I don't know if and what kind of energy a memory consists of ... But if it is, then it should be really huge, esp. considering the images stored in a computer, even in compressed form! This shows clearly that memory cannot be located/stored in the brain, as scientists try in vain to establish since a long time ago!

I'm not sure about this. For example, companies are already storing digital text and image codes using DNA. A cubic cm of DNA is capable of storing 5 petabits of information. The actual total amount of information for something with the energy of the brain itself would necissarily be far larger than what is coded in ways that are usable for the brain's components, because you'd be talking about the total phase space of the brain, all the possible molecular arrangements that are compatible with the observed macrostate. The amount of potential configurations and permutations is astronomical. This huge amount of entropy is true even for a mole of hydrogen gas sitting in a liter container at room temperature. Just think about how large Avogadro's number is. -

The problem with "Materialism"

Nevertheless, if I write something that gives you the shits, your pulse will accelerate slightly, your adrenals will uptick a little. But nothing physical would have passed between us.

I don't see how this holds. If we had you both hooked up to various types of neuroimaging devices we could see correlates of both the process of writing the text and the process of reading it. We could also predict, at the scale of neurological substructures, where in the brain activity would increase during those activities.

Communications via the internet are also understood fairly well. The entire process relies on physical theories, theories backed by significant observation.

To be sure, when you get down to small enough scales, it is unclear how language is produced, or how the electroweak force that carries your message through the internet does what we see it doing in the world, although the force is fairly well understood at the scale of transistors and fiberoptic cables relevant here. The problem of positing something extra here is, what does it help explain? And if those physical causes aren't responsible for those phenomena, why don't the phenomena of language and internet debates show up elsewhere in the world, in places where people and the internet are absent?

Part of what physics tells us is that information is protean, and it shouldn't be susprising that a code in the form of human language can be transmitted into other physical forms, especially given we have had written and spoken languages for millenia.

Thus people today stop at the laws of nature, treating them as something inviolable, just as God and Fate were treated in past ages.

I think it's understandable. Claims that don't cohere with existing knowledge should be the targets of extra scrutiny. Otherwise, you will end up with a hodge podge of contradictory claims and an incoherent science. If you accept a bad claim that is coherent with existing scientific laws, it will lead to some misunderstandings, maybe wasted research dollars, etc., but it can eventually be identified and removed.

If you let in a bunch of bad claims that violate your existing laws, you now need to rebuild the system. It becomes a web of caveats and uncertainty, making future research harder. The bar to entry should be higher, and if the phenomena is actually there, it should be able to meet this bar.

However, obviously this can go too far. Almost all paradigm shifting discoveries, by their very nature, end up upending scientific laws. Claims of woo could have been used to discourage plenty of essential theories, such as the idea that nature writes genetic traits in a language-like code, relativity, etc.

Numbers, grammatical rules, the principles of logic, scientific principles - none of these have a scientific explanation and cannot be meaningfully reduced to physical laws. They also can’t be meaningfully accounted for as products of evolution either without reducing them to biology,

This is a very interesting point I will return to when I have time. People absolutely do, with varying degrees of evidence, try to reduce logic to biology. The universe has laws that obey logic, so in turn, animals have a "logical sense," much like they have a sense of sight. Certainly some basic logical ability seems innate. Healthy human babies will register surprise when experimenters preform magic tricks in front of them that give illogical results.

However, this is a big claim made using a small amount of evidence.

I think the much larger issue here is how you can claim that science, as a system of methodologies for ensuring correct logical inference from empircle data, proves that logic comes from nature, when if logic did not obtain, we would have no reason to believe the findings of science.

This is circular. And while circularity is not always fatal (natural numbers, Liebnitz' Law, etc.) this seems like a particularly vicious circle.

Pragmatist approaches side step this circularity, but they do so by saying the best we can do is to assume that logic is posterior to the findings of science.

However, there are other issues here.

Why are the methods for proof in mathematics so different from the sciences?

Why do mechanical computing machines and electric computers get caught in endless loops due to seeming contradictions? Why is does the logical reversibility of an operation equate to entropic reversibility (there are some challenges to this)? Why does the law of information entropy, possible messages, turn out to be the same thing as physical entropy? There are a bunch of these. The whole reason quantum cryptography is so airtight is because listening in requires a contradiction, so it's not an uncommon claim that even if QM is totally replaced, the cryptographic methods will continue to hold.

reply="180 Proof;654143"]

These abstracts are, in fact, generated – via autopoiesis – in ecologies of (human) brains

This seems problematic as an explanation. I don't see any issue with the claim as it respects one instantiation of any of the abstractions WF mentioned, but I don't see how this can be anywhere near a full explanation.

Because is abstractions are actually just names for processes in the brain, or thoughts, it means propositions about abstractions would actually just be propositions about brain processes (thoughts or beliefs). This fact incurs a high metaphysical toll, especially as concerns predication.

For example: "Circles are shapes," seems like it has to be radically rewritten for it to have a truth value if circles and shapes are only existant as brain states.

This in turn deprives a wide array of useful syllogisms that use abstract scientific terms of their meaning. At its most expansive, the claim that language is existant only in brains, instead of being tied to a huge host of referents, reduces all propositions to claims about brain states. But then if our propositions are actually about brain states, then the claims of science that led us to believe that language is actually existant only as brain states turns out to only have been propositions about brain states themselves. O_o

Edit: I should note that the above problem is not a problem for physicalism, even reductive physicalism. It just can't be that language is an emergent phenomena of brains alone. If language is an emergent phenomena of relations between many things, including brains, but also the physical referents of language, then this problem doesn't emerge. It's also unclear if human language, insomuch as it is a code for storing and transmitting information, is unique. DNA had been around far longer than human beings, and represents a code that does many of the same things that language does. -

The problem with "Materialism"

This is a common, but I think unfair rebuttal. After all, if the eliminativist vis-á-vis abstractions (or qualia) is correct, we shouldn't expect them to be able to overcome this illusion. So if they continue to say they feel tired, or advocate against racism, etc. it is only because the illusion is so powerful, which is exactly what their theory predicts. Before enlightenment, chop wood carry water, after enlightenment, know that you necissarily must chop wood and carry water.

Right, there shouldn't be a need to reduce abstractions to claim they are physical. This was a major problem for me for a while. If someone challenged my non-reductive physicalism, I'd feel the need to claim that "x is actually an idea, so x is neurons," which of course is the type of reductionalist argument I wanted to avoid because I thought it had many serious flaws.

I realized the error one day when I started trying to explain supply curves as attitudes held by producers in an economy in terms of their brains. This makes no sense. A supply curve obtains as a complex interaction between many people, laws, enforcement agencies, the natural enviornment, disease, technological development, etc. It cannot be reduced to neurons. Doing so appears to also force you into a sort of linguistic nominalism, where people don't actually make propositions about things in the world, but about ideas about things in the world, or about words (e.g., Sellars).

However, I think the evidence for epistemological realism is quite strong, and so I definitely don't want to embrace the idea that abstractions are just words and connect to nothing. I also don't want to claim they are their neuronal correlates, because they also include references to non-human things, and making this claim will tell people you actually don't even know what is meant by "supply curve," since it necissarily includes things like the amount of a given metal left in operating mines. -

The problem with "Materialism"

Have you presented your methodological physicalism here? I certainly wasn't responding to it in the prior posts because I'm sure I haven't read it, I was simply speaking generally about the topic. Hence, "I can't tell you if your idiosyncratic version of the word has problems because I don't know what it entails.

All I know about it is that it doesn't make ontological claims and all the scientist agree on it. But since I'm not aware of any disagreements I have with the methodologies employed by most scientists, as best I can tell, I'm actually in agreement with you.

There are some takes I've read where 1+1 "causes" 2, with the caveat being that these are generally eliminativist vis-á-vis causation as a whole. There was a quote from Russell posted somewhere around here on eliminating cause the other day.

Anyhow, some arguments state that "cause" is simply identity, generally because "things" are actually processes. So, if cause is identity, and 1+1 = 2, the proposition holds, although some pretty heavy baggage comes along with it.

I personally think trying to get rid of / transform cause muddles more than it clears up.

Abstractions never cause physical effects?

↪ZzzoneiroCosm Correct. (All too often "idealists" make this mistake.)

I had forgotten, this is a point I had meant to comment on. Abstractions generally have to be able to cause physical effects for a physicalist. Otherwise you end up paying the hefty metaphysical toll of embracing eliminativism towards abstractions. That may be a toll worth paying, but it seems a high one for a philospher.

Example: Racism is a socially constructed abstraction. Racism results in physical effects, such as hate crimes and measurable discrimination in the provision of physical public goods to the victims of racism.

Now, if a someone wants to say, "sure, that example is true, but it is true because racist ideas are actually physical processes in the physical bodies of people, and it is those people's physical bodies that carry out racist acts."

That's fine. Rebuttals of this type often take the form of claims that reduce racism down to the the level of "brains" or "neurons." This is a coherent claim, although it does entail reductivism in the aforementioned form.

However, it seems like this response is making the physicalist take extra steps (and potentially embrace reductivism they might not otherwise want to embrace). If abstractions such as "racism" are actually just names for physical phenomena, then there is no reason for the physicalist to have any qualms at all with saying that abstractions have physical effects, since physical phenomena can obviously cause physical effects.

If the argument is instead that:

A. Abstractions exist; and

B. They don't cause physical effects,

Then the position is more problematic for physicalism. Because clearly people think about abstractions (case in point, this site). However, if abstractions can't cause physical effects because abstractions are not physical, then how is it that people, who are physical systems, can interact with them? This seems like a position that is in serious danger of falling into "woo."

A way out might be for us to say that abstractions are a sort of emergent phenomena, that abstractions only exist in human minds as the results of thoughts. "They exist as neural activity only," could be a phrasing. However, this argument isn't actually getting away from the problem, since neural activity is responsible for almost all vertebrates' actions, which are physical effects, so it is still to be seen why abstractions are different.

Plus, even if we have a system where abstractions are somehow isolated from ever having physical effects, but still exist as physical entities within the physical constituents of minds, you still run into the problem of violating Ockham's Razor. If all meaningful effects are physical, and abstractions cannot cause physical effects, then abstractions have no explanatory power. But if abstractions have no explanatory power, why are we positing additional entities to explain something when less will do?

Which leads to the last option, eliminating abstractions. People once thought mental illness was caused by demons. We now know that demons have no explanatory power in that regard. Perhaps abstractions are the same thing. Like qualia, abstractions can be eliminated from our lexicon, at least as respects serious thinking about causality. This solves the problem of how physical people can think they can access abstractions, while said abstractions have no physical effects.

This radical line seems to come with several difficult consequences. First, eliminating abstractions necissarily means jettisoning most of the social sciences (and it is unclear how much would remain of the other sciences). Unless the eliminativist has a substitute for these with more predictive strength than the existing systems, it doesn't seem that jettisoning abstractions is actually clearing things up. Not to mention that it also seems difficult to explain other sciences when appeals to systems, networks, complexity, etc. have all been rendered meaningless.

Perhaps this is why there are no well known philosophers who are eliminativist vis-á-vis abstraction. It's easier to stake your claim on eliminating qualia, the heart of subjective experience, than it is to deal without abstraction. Plus, there seems no reason to pay this high price, since the claims of eliminativism are generally that whatever is being eliminated is actually something physical that is different from what naive realism thinks it is. But in that case, why not just say abstractions are physically instantiated?

This means of avoiding eliminativism isn't too far off an embrace of trope theory, or some sort of language based nominalism, versus having to embrace some sort of all out hyper-austere nominalism where only particular physical entities obtain and their traits are all unanalyzable truths.

Anyhow, if anyone thinks they have a physicalist system where abstractions aren't eliminated and still cannot have physical effects, but these issues don't obtain, I'd love to hear them. -

The problem with "Materialism"

The relevance is that the problem of many versions of physicalism being definitionally indistinct, at times to the level of being vacuous, is not a problem of my making.

It's a "problem" of your own making, Count, because non-reductive physicalism is not "an ontological position" but a methodological paradigm (i.e. an epistemological criterion / paradigm)

It's a problem of soundness for the arguments and systems generally associated with physicalism. Obviously, it is a problem for not all such systems. I specified non-reductive physicalism because reductive versions tend to be better at avoiding this, on average at least (e.g., old claims that nucleons represented fundemental universals, while effectively killed by future particle physics, is an explicit claim.)

I can't tell you if your idiosyncratic version of the word has problems because I don't know what it entails.

I can tell you that when I've run across "methodological" physicalism before some have been sound (generally pragmatist), others have essentially been a bait and switch for ontological physicalism, and still others have been sound, but have nothing "physical" about them, which makes me suspicious that they were actually put forth as a means of arguing for ontological physicalism without being forced to actually defend it. As far as their strengths as epistemological systems, it depends on how expansive the claim is. Are the physical sciences a way of knowing things, of the only way of knowing things. -

Reality does not make mistakes and that is why we strive for meaning. A justification for Meaning.

I give up after this. It was a tangential thought anyhow, and I don't even necissarily disagree with the general gist of the post, in the sense that people may ascribe anthropomorphic purpose to nature for psychological reasons (although the converse is true too).

It's wrong because nature contains meaning; this is a basic physical fact, empirically verifiable and logically necissary. If it was meant as, "does nature as a whole have meaning, from a universal perspective," it's wrong because it misunderstands the nature of information.

Suppose Human nature's personal need for 'meaning and purpose' only proves writ small Blind nature's impersonal lack of 'meaning and purpose' writ large?

Meaning = definition = reduction in uncertainty about a system = information = entropy. This is not really controversial. Information being physical has held up to experimentation and been a boon to physics as a concept.

Talking about "blind nature" having meaning doesn't fit the concept of meaning because information, if it exists, obtains between two or more systems. Nature as nature can't be said to have meaning (in the context of naturalism). That would be saying it somehow has or lacks a reduction in uncertainty (information) about nothing.

Suppose, therefore, that individuaally and collectively fulfilling this personal need is merely an illusion we employ to get ourselves out of bed every morning and/or with which to variously sedate our despair (and that works only as long as we remain in denial that our 'meanings and purposes' are just (mostly adaptive) illusions)?

The meaning, reduction in uncertainty, about nature for people (physical systems interacting with other systems) can't be fully illusory. That would be saying minds somehow create information that doesn't exist. This would be woo, indicative of some sort of supernatural type of information or access to information, solpsism, or idealism. I've gathered that you are not a fan of woo, so this seems like an issue.

Information channels can have errors. When you get to complex systems that have computational abilities and subsystems that attempt to generate inference from information, you can get strange, incoherent, and false representations, but the meaning has to be in nature.

This could be applied to the concept of purpose, such that systems can have purpose (e.g., life - self replication), but I think that is going way out on a limb. Purpose seems more like an abstraction, and doesn't exist in the essential way meaning/information does.

"...how to interpret it."

Interpret it. It what?

- the conclusion

- information content

- universe

- perspective

- zero

- this (what ever "this" is)

I was thinking in terms of a thought experiment where you somehow magically step outside nature and observe it through supernatural means, which is the only way to get information from nature writ large.

You can conclude:

1. That entire experiment is in error and misunderstands how the concept of information works, my view.

2. That information about nature qua nature, essential non-perspective information, is impossible without magic, relegating it to woo.

3. Is a coherent use of the concept of information, but shows that such information is impossible to obtain, and necissarily indeterminate.

Maybe this helps:

The proposed existence of this information imposes some fundamental questions about it: “Why is there information stored in the universe and where is it?” and “How much information is stored in the universe?” Let us deal with these questions in detail.

To answer the first question, let us imagine an observer tracking and analyzing a random elementary particle. Let us assume that this particle is a free electron moving in the vacuum of space, but the observer has no prior knowledge of the particle and its properties.

Upon tracking the particle and commencing the studies, the observer will determine, via meticulous measurements, that the particle has a mass of 9.109 × 10–31 kg, charge of −1.602 × 10–19 C, and a spin of 1/2. If the examined particle was already known or theoretically predicted, then the observer would be able to match its properties to an electron, in this case, and to confirm that what was observed/detected was indeed an electron.

The key aspect here is the fact that by undertaking the observations and performing the measurements, the observer did not create any information. The three degrees of freedom that describe the electron, any electron anywhere in the universe, or any elementary particle, were already embedded somewhere, most likely in the particle itself.

This is equivalent to saying that particles and elementary particles store information about themselves, or by extrapolation, there is an information content stored in the matter of the universe. Due to the mass-energy-information equivalence principle,22 we postulate that information can only be stored in particles that are stable and have a non-zero rest mass, while interaction/force carrier bosons can only transfer information via waveform.

-

Reality does not make mistakes and that is why we strive for meaning. A justification for Meaning.

I suppose I wasn't being very specific. I meant, speaking of nature either having or lacking meaning in the context of a naturalism informed by modern physics is potentially using the concept of meaning where it isn't applicable.

Something's meaning, its bearing, information, value, significance, [insert synonym here], etc., for something else obtains as as an interaction between two physical systems, or a system and its environment (another system). Information transfer and erasure are physical interactions (e.g., Landauer's principle). As a relationship between two systems, it isn't something you can say nature has or doesn't have. That'd be akin to saying that "the universe has gravity." The universe contains meaning, it does not have meaning of itself; it's the difference between being able to ask yes/no questions about something and saying it posseses answers, and saying something possess questions.

This statement relies on information/entropy being the same thing as, or closely related to, "meaning." If propositions can be about physical objects, and if sensory inputs are reducing our uncertainty about physical objects, this relationship must be the case. Information cannot be created or destroyed. If we have information about a system, it is coming from somewhere outside ourselves, since we are a separate, finite system.

To be sure, the information is coded quite differently within an animal. The channels are imperfect, so there is a massive amount of compression. There is added complexity in the system, so in people you have abstraction, analysis, the same information going through feedback loops. But at the end of the day, a thing's meaning, the sense of what it is, our reduction in uncertainty, is information. This concept doesn't apply when considering what a system is of itself.

Second, the universe necissarily contains meaning. Nature could not exist if a single coherent yes/no question could not be asked of it.

Maybe I'm misunderstanding what people mean when they say nature does or doesn't have meaning. If the question is more "does it have a goal?" I think that is a question that is at least conceptually sound. -

The problem with "Materialism"Well, I could have just told you that isn't what anyone normally means by "physicalism," I just figured it would be helpful to show that's the case.

-

The problem with "Materialism"

Exactly, that's the tricky part. If forced, I'd say that I am a non-reductive physicalist, leaning towards being ontologically agnostic. Whereas I'm happy to go further out on a limb in promoting a physicalist philosophy of mind.

Even in principle there aren't any such "entities".

Righto, it was a rhetorical question.

It's a "problem" of your own making, Count, because non-reductive physicalism is not "an ontological position" but a methodological paradigm (i.e. an epistemological criterion / paradigm) employed in the cognitive / neurosciences. Otherwise, if "non-physicalism", then account for

That's a fine position, but it's an idiosyncratic definition. Physicalism is generally understood to refer to a group of ontological models. The SEP article on physicalism is largely about issues in metaphysics (identity, supervenience, modality, etc.). The opening of the Wikipedia article (and isn't Wikipedia the world's book of democratic record?) starts off with:

" physicalism is the metaphysical thesis that "everything is physical", that there is "nothing over and above" the physical, or that everything supervenes on the physical. Physicalism is a form of ontological monism..."

The peerless Google algorithms appear to be returning an entire page about physicalism as an ontology as the top results.

I'm not sure what is particularly physicalist about "physicalist epistemological methods." The same methods are employed effectively by non-physicalists (Roger Sperry, Wilder Penfield, etc.). There are plenty of these folks, enough that articles about the problem of an excess of crypto-dualism in neuroscience are regularly published. Personally, I'm more surprised by how not dominant physicalism is in philosophy of mind. Only 52% of people specializing in the field opted for "accept or lean towards: physicalism," in the latest PhilPapers survey, a large decline from 70% back in 2009.

The issue I tend to come across in my reading and discussions is that physicalism gets conflated with the methods of science. Which to be fair, is understandable given science generally gives us physicalist answers. A problem arises when this leads to critiques of physicalist ontologies being taken as necessarily critiques or rejections of scientific methods. This is at least easy enough to clear up, but a more pernicious problem is ontological cheating, where scientific findings are used to imply metaphysical claims without being explicit about what those claims are, and what would falsify them.

For an obvious, and over the top example, some Quora post I saw today resolved the entire issue of universals once and for all because "red is a light wave with a 620nm wavelength." This one is easy to dismiss, but there are plenty of less obvious, but similar lines out there that essentially assume "fundamental properties and facts are physical and everything else obtains in virtue of them,” without stating so.

Edit: Should note that I notice this sort of ontological cheating far more in articles that are attempting to critique non-physicalist metaphysics. It's generally not quite as bad when there is debate about different types of essentially physicalist metaphysics, provided that one side doesn't mistake the presence of any metaphysics at all as somehow being anti-physicalist magicspeak, which you do see happen. -

Berkeley and the measurement problem

This is essentially true from a number of perspectives outside QM. Whether or not it is true for QM depends on your definition of "perceived," and the interpretation of QM used, specifically the ontological status of wave functions. I do not believe your quote would apply under most interpretations because wave functions are understood as existing. Second, the phenomenon you would be referring to would be wave function "collapse" or decoherence, not the measurement effect.

"Observed" and "perceived" are loaded terms, and it is somewhat unfortunate the CI version of QM uses the word observer in English, because it causes a lot of confusion. In normal language, a rock does not perceive things, nor does a photoelectric sensor. In CI QM though, a photoelectric sensor can absolutely be an observer. Macroscopic objects like rocks can absolutely cause decoherence.

Decoherence as a concept has its own problems and critics, but I think the gist is easier to get than the CI language. When a quantum system, a light wave for example, interacts with its environment, phase information about it gets scrambled with the environment. We say it loses "phase coherence," because it can no longer be represented as the original wave function. So, if you think about the double slit experiment, and how the light waves interfere with each other, decoherence is the opposite of this phenomena. You can think of quantum elements that decohere as becoming entangled with the environment.

So, "being observed" can be a bit misleading because of the way the word is normally used. Other explanations will describe the shift occurring when "information is acquired about the system," or describe it as a sort of friction between the system where it is essentially shedding information instead of heat (I don't like the friction analogy much because it can twist concepts if you're already used to thinking of energy as information, and it uses a classical image of space, with objects with identities rubbing against each other that is not the best for understanding QM).

----

However, the statement is true from a methodological perspective. If something truly cannot be observed, either directly or indirectly through its relationship with observable entities, not by us humans, and not by any sort of hyper-advanced species, then it cannot be said to exist using empirical criteria. For it to be said of a thing that it is true that it exists under such criteria, it must be observable.

We could push this further. We could imagine that there are other universes, with different laws of physics, and different entities, sitting outside our own. We can never interact with them. However, we would still say that, if such a universe existed, then those things would have being, even if from a purely empirical perspective, their being and not being are co-identical.

But what about a hypothetical particle the "nullon?" The nullon would be a fundemental particle or field, but unlike the other fundamental particles, it interacts with nothing. Nullons permeate the universe, but nullons do not have any relationships with anything else in the universe. Additionally, nullons do not interact with each other. If we envision them as particles, we can imagine them just passing through each other without a trace; they cannot be observed, even by other nullons.

Can the nullon have being? I would argue it cannot. It's being and not being are forever and always, for all things, co-identical. If it shares an identity with its not being, even if it is, it cannot be.

Ironically, under Leibnitz Law, it appears it could have identity. If "x is identical with y then everything true of x is true of y" would hold for the nullon, although it would also share an identity with all non-existent things. I'm aware of ontologies that hold that just such a category is definitionally a part of being, and essential for it as creating a definition for being. In those cases, the reverse of your quote is true "there must be things that cannot be observed for things to be."

The nullon sounds a bit silly, but this is essentially the thing substratum metaphysics argues exists, i.e., that there are entities of pure haecceity. It's understandable that people do this though, because if you instead posit that things are merely the universals they exemplify of a collection of tropes, you end up with some other weird, circular issues.

There is another sense that the statement is true in too. In order for anything to be for anything else, it must interact with it. Its being and non-being cannot be co-identical for it. However, in the framework of physics, you can't meaningfully talk about taking up an observation point that isn't physical. Your observation point must be a physical system, it cannot be magic. This has the effect of also making it a necessity that X has to interact with Y for it to be "for Y." Talking about some sort of "absolute being" in physics doesn't make sense, except as a useful simplification for understanding concepts. -

The Decline of Intelligence in Modern Humans

Just making conversation mostly. Sorry, 95% of that post was me just chiming in, the only reason I quoted the two references I saw to the Flynn Effect is that it sounded like they might have been given in the sense that the Flynn Effect shows that intelligence is increasing, not decreasing, which is indeed what the term meant until quite recently, when decreases began to show up.

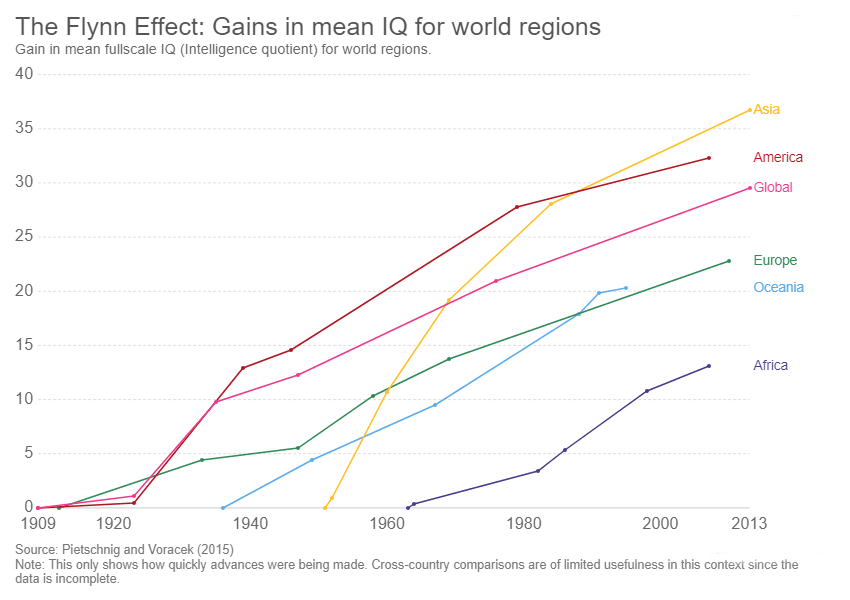

The graph is growth in scores from regional means so you can't compare between them; growth is relative, not absolute. Because both genetics and enviornment influence g, you need to scale IQ tests, with 100 as the mean for a given population. This is why they are often critiqued. Scores vary depending on if you use a national mean, or a mean using some sort of ethnic identifier (always poorly defined to varying degrees, and worse, self reported). The mean also changes over time, so 100 today would be significantly higher than 50 years ago. It's also meant for age cohorts.

Ideally the mean should always be 100 for a given population. That population should be selected based on genotype, and for a given region with similar economic development. Instead, the mean from Western European nations is used, or a mean of "White" Americans to set 100. -

Reality does not make mistakes and that is why we strive for meaning. A justification for Meaning.

Right, that's another interesting point. To have an absolute standpoint would require you to have a memory essentially equivalent to the energy of the universe as a whole... maybe.

You can compress information in ways that are fully reversible. The simplest example I know of is simple image compression block coding. If an image is almost all black pixels, with a white square in the middle, instead of coding each black pixel, you can instead code them as a block of consecutive black pixels (i.e., "0 x 10", versus "0000000000"). Interestingly, trying to compute the absolute minimal way in which a piece of information can be stored, the maximum compression that allows for irreversibility (Yao entropy or Kolmogorov complexity), results in logical contradictions that throw computation into endless loops.

Interesting to consider when people make analogies to reality as being like a "simulation" or "computer program," anyhow. I think those comparisons tend to mislead more then they elucidate though. -

Reality does not make mistakes and that is why we strive for meaning. A justification for Meaning.

I was saying that could be taken as evidence of "blind nature's lack of meaning." I think the more supported conclusion is that speaking of "blind nature" or nature qua nature, is the thing that isn't actually meaningful.

There are, of course, plenty of similar armchair psychologist reasons that people have for asserting the meaninglessness of nature, so IDK if there is much to say about the other part of the post. -

The Decline of Intelligence in Modern Humans

The fact that the Flynn Effect has reversed in developed countries is a well-established and replicable finding.

Explanations abound, complex systems generally overshooting and then ratcheting back to equilibrium:

https://scholarworks.utep.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2339&context=cs_techrep#:~:text=This%20steady%20increase%20in%20intelligence,who%20actively%20promoted%20this%20idea.&text=While%20the%20intelligence%20scores%20have,grow%3B%20instead%2C%20they%20decline.

Changes in the environment:

https://www.pnas.org/content/115/26/6674

There are many more. One thing to note is that it is not caused be genetic changes in the population. This is a common misattribution. Because distinct genetic groups tend to vary in IQ scores, the initial explanation for this shift could be that the underlying genetics of the population are causing the shift. While it is true that these changes cause a shift in mean population IQ within national borders, the Flynn Effect and its reversal are observed within population groups, controlling for variance in heritage.

But here things get very complicated. Obesity is highly heritable. Your relatives' BMI is highly predictive of your own. However, environment clearly plays a role, as obesity was uncommon until quite recently. Intelligence is similar. It is highly heritable, holding most things mostly equal (e.g., looking at twins who are both raised in the same country, even if the socio-economic status of their parents varies quite a bit.)

Changes in environment appear to account for the reverse Flynn Effect. There are some proposed culprits. Half of all plastics were made since 2008. The environment is now saturated in microplastics in developed countries. The average American consumes a credit card worth of plastic a week. Plastics work as endocrine disruptors and may have profound long term, ongoing effects on the body. Obesity is another macro level trend in populations caused by shifts in the environment and there are mechanisms through which it may impede cognitive function. Exercise is shown to delay the onset of dementia, prevent depression (which in turn negatively effects cognitive performance on tests that measure G), etc. and people are increasingly sedentary. The water supply is also awash in pharmaceuticals such as birth control, anti-depressants, etc. which also have a possible connection.

Point being, there are a lot of things that could be causing it, but it is definitely there, even when just considering within family effects. Then, for population means, genetics is also a factor that can raise and lower means. In general, higher IQ past a certain point is negatively associated with number of offspring. So aside from the environmental effects, there is also a selection element where genes associated with higher g may be selected against in the current environment.

Also of note, the effect is extremely large:

A 30-point gap, two standard deviations in most scoring systems, is the difference between mean IQ and many definitions of mental retardation, or mean IQ and common definitions of "gifted." A long-term trend that reverses the Flynn Effect has profound implications for future societies. -

Reality does not make mistakes and that is why we strive for meaning. A justification for Meaning.

If we exist within reality then we are one part of the blue print of reality and if no event which occurs within reality can be classified as a mistake than our ability to create meaning for our own is existence is not a mistake.

Good points, but I think the definitions might need some work to describe what you are getting at.

If we rephrase the above, could it mean, "no event occurs within reality, for which, if we knew all the conditions for it (the blue print), we should be surprised?" That is, if we know how the "right" answers come to be, we should never be surprised by them.

This has two likely unintended consequences.

1. This would mean the information content of the universe, measured in physics/information science as the amount of surprise we have about what happens in a system, is zero using an absolute frame of measurement. That is, nothing is mistaken so nothing should surprise us, and the actual entropy of the universe from an absolute viewpoint is zero, meaning there is nothing to know. This also implies hard determinism from the bottom up.

This is counter intuitive; it tells us that only by having incomplete information can we have any information, total information = 0 surprise = no information. Maybe there is something here, this is indeed what Hegel gets at with his oppositions of X and Y, where pure Y turns out to be X because it has nothing by which to define itself aside from abstraction, but many people don't like the dialectical. (He does this with nothing and being in PhS and pure freedom in the Philosophy of Right.)

It could also just be telling us that our methods for measuring entropy are missing something. That they only work if you accept that you are a system made up of parts of the universe measuring other parts, arbitrarily defined as systems.

Thus, speaking of measuring the universe as a whole is a meaningless concept, and we cannot logically apply our rules to everything. This is somewhat suggested by the fact that the information exchange formula for the universe as whole would be zero following the holographic principal, since the surface of the universe contacts nothing. Also by the fact that thought experiments positing magical observers without physical parts that hang out in vacuum allow you to violate the laws of thermodynamics.

2. At the lowest level we can probe, the universe seems stochastic, modality is exhibited in wave functions. We can only know of probabilities of X (e.g., types of spin) and measuring what X is causes changes in the system (collapse). But our zero information system should have no surprises, so this probabilistic nature of QM can't be there, else mistakes can always arise.

Perhaps the universe isn't probabilistic at small scales, perhaps there are hidden variables that hold the spin of particles in wave form. However, against this point is the fact that experiments on Bell inequalities consistently tell us that this is not the case, so far. So surprise appears to be an essential part of reality, which means that "mistake" must become a more amorphous definition. It means not one outcome versus another, but rather a huge spectrum of outcomes that you can be surprised about no matter how much you know.

Another problem might be time. Time now generally needs to be understood as space-time. Experiments in quantum tunneling seen to suggest the possibility of effects in time breaking the laws we thought we had found for it, waves crossing barriers before they have left, although this needs more experimentation.

However, if time is relevant to an observer, but at the fundemental level, particles do not have their own identities, what do we make of that?

I think there is something here to this perspective in that a system can only have information about other systems based on which systems it has been able to exchange information with.

"Objective" reality appears to require an infinite, absolute viewpoint to at least be posited as possible. It does not currently seem possible, and were it to exist, we run into the problems above vis-á-vis our current conceptions of information.

This doesn't imply meaning in the sense of sentience however. The light sensor in your camera is a system and can act as an observer in QM, but I think this fact still has implications for how we think of meaning.

This is one way to take it. The conclusion that the total information content of the universe from an absolute perspective is zero would jive with this depending on how you want to interpret it.

However, I think it does run into ontological difficulties. How does a system with no surprise, no information, produce information for systems within itself and why does it seem to necissarily do so?

You can posit the findings of scientific inquiry as a series of unanalyzable facts, but you're still left with the issue of how such facts can come to be known, seemingly due to logical necessity.

And while human logic is fallible, and our logical intuition can be seen as a by product of evolution, it certainly does seem to be saying things about the way things actually are. It's how we can determine said brute facts, and the ground for understanding them. If you feed contradictions into quite different computational devices from the mind, modern computers or mechanical ones, you end up with infinite loops, halting problems. Incomputability shows up as a physical property. -

Debate Discussion: "The content of belief is propositional".I think both sides of the beliefs versus objects debate get something essential right.

If you look at it from a cognitive science perspective, both are making accurate statements about how thought is assumed to work.

First, information comes to a person from outside that person. Solipsistic concerns aside, I don't think this is a controversial point. From a physicalist standpoint, it is necissarily true as the mind can't be generating this information itself.

Thus, sensory inputs are of objects. Statements about those inputs are essentially about the objects that are known through those inputs, not about the inputs themselves. We have specific language we use when we want to specify that we are talking about our perceptions of an object, not the object itself, as when at the top of a mountain we say "the car looks small from here."

When I say, "the used bumper I bought was rusted through," I am making a statement based on my beliefs, based on the sensory experience I have of the thing, but the statement is not about those things, it is about the bumper. If the mechanic hits it with a wire brush and just an outer coating of rust falls off, revealing a solid bumper, I will except that my proposition was false, which only works if my proposition was about the actual bumper.

However, the belief side of the argument is getting at something just as essential, which is that the proposition is only ever about the object "as it is for conciousness." This is essentially what Kant's "Copernican Turn," got at, but we understand how cognition works much better today, and how this is true in more detail.

There is about 1.509 bits of information in a proton, 0.187 bytes . The content of a gram of hydrogen gas would be around 1.87 * 6.023 10^22 bytes if we're just talking about the details that can be measured about individual protons, let alone getting into the total entropy of the phase space. (Unrelated: you can get that from normal Boltzmann entropy S = k B ln Ω, just by swapping the natural log for log2, which I found made picturing entropy far more intuitive because I could think about true/false values).

The human brain has an enormous memory potential, about a petabyte, or 2^50 bytes. But even with this massive potential, it's obvious that it could only code and store an infinitesimally small amount of the total information in the objects it hopes to represent. Aside from that, human sensory organs are also far too limited to get at most of this information. Additionally, there is a huge amount of noise in the channels through which the mind accesses this information, as well as errors in the coding process going on in the brain itself.

So a proposition, itself something formed in a code, is necissarily referencing another code that is an extremely compressed and often error ridden representation of an object (or more confusingly, mental abstractions with no direct ties to specific objects, such as propositions about "all cats").

A proposition is necissarily based on and vetted using codes, regardless of if tools are used to help the vetting process.

"The car is red," can be a statement about an actual object, but it's about how that object is to conciousness. This must be, since redness itself isn't a property of light waves except as experienced in conciousness.

I think the confusion comes from thinking that information in the form of codes containing information has to be somehow different in kind from the source of the code. It is different, in that the information is compressed, is stored differently, and has errors, but it doesn't become something totally different. If this were true, the same digital picture shared over and over across the internet is actually millions of different pictures. Different copies of War and Peace would contain different information, and so your propositions about War and Peace wouldn't just be propositions about beliefs about War and Peace, but propositions about beliefs about a particular copy of War and Peace. -

Jesus Freaks

Yeah, the whole idea of the human mind is incredibly fascinating, being experiencing itself everything emerging from... no one really knows.

I think I also see the source of confusion here. What you're referring to as unique to the brain is generally called complexity, which is amorphously defined, but generally has to do with how networked a system is, as well as its lying somewhere between too much order and too much chaos. Going back to the example, supercomputers might have more computational power than a brain, but they are orders of magnitude less complex.