Comments

-

Who do you still admire?Your question is one that has troubled me on and off over the past few years. On quite a few occasions in discussion I have wanted to pick an example of a 'really good person', for some reason relating to the discussion. And I have run into uncertainty. The famous examples like Gandhi and Martin Luther King have well-known downsides. I have been tempted to name Dietrich Bonhoeffer, but decided not to do so because I felt certain somebody would dredge up some unkind thing he had done once, which I hadn't known about, and thereby ruin another of my 'heroes'.

I have come to a sort of partial resolution by accepting that, just as (IMHO) there are no Bad people, only Bad (or, more accurately, Harmful) acts, so there are no Good people, only Good (or, more accurately, Helpful*) acts.

So I can admire Russell's courageous stance against the Great War, while regretting the way he conducted some of his sexual relationships. Ditto for Martin Luther King. I can even admire Margaret Thatcher's toughness and courage, despite abhorring most of her policies.

This approach is much less vulnerable to disappointment, as it starts by recognising that we are all fallible, and even those whose acts we live in awe of (eg Wilberforce's campaign against the slave trade) will almost certainly have done some things in their life that were mean (Wilberforce was also a punitive, prudish 'morals' campaigner).

Or look at it like this: in a life of seventy years a person will perform hundreds of thousands of acts that involve other people. Imagine we could put a 'kindness' score on every one of those acts. Then those scores will form a distribution. It may look like a bell curve, or it may have a positive or negative skew, or even be more unusual (eg multi-modal). But there will be a Worst act one has ever done - the one at the extreme far left of the distribution.

What are the chances that that worst act will be no worse than neutral? I'd say virtually nil.

We can apply that the other way around too and ask what would be the kindest thing that Stalin, Hitler or Pol Pot ever did. I'd expect the chances that it would be no better than neutral are again virtually nil.

In short: for me the answer is to seek to emulate not people, but their admirable acts.

The second thing I wanted to mention is that there is a distinction between the policies one promotes and one's private behaviour. The objections to Gandhi, King and Russell are about their private behaviour, while the policies they promoted are widely admired. Other good examples of the policy-good, personally-bad phenomenon are Charles Dickens and Henry Lawson. Maybe JFK too, depending on one's perspective.

I expect there isn't a negative correlation between the kindness of one's policies and that of one's personal behaviour, but sometimes it seems as though there is.

The list of Goodies you came up with was an example of this apparent (and probably illusory) negative correlation. Both CS Lewis and GK Chesterton promoted policies that I consider extremely harmful, preaching belief in eternal Hell for one thing, and that failure to conform to sexual norms was deserving of Hell. But everything I've read suggests that they were both lovely, kind individuals on a personal level. The play Shadowlands paints a very moving picture of Lewis, and Chesterton managed to be great friends with his political foe George Bernard Shaw - despite Shaw being a notoriously prickly person.

* The Buddhist adjectives for these two H words are Skilful and Unskilful, which I find to be a valuable perspective. -

Objections to the Kalam Cosmological Argument for God

Fishfry and, I expect most of the others that have responded to your thread, is/are perfectly familiar with Hilbert's Hotel, and why it is not an argument for any statement other than 'aren't infinities interesting?' Ditto for Aristotle's notions of potential and actual infinities.To understand why this is you should google up and read the mathematician David Hibert's famous thought experiment , "Hibert's Hotel". — John Gould

Kalam has been discussed ad nauseam on this forum and its predecessor. You are very unlikely to come up with any arguments in its favour that have not already been considered and dismissed. Don't you think that, if it stood up to scrutiny, non-religious logicians might have noticed and written supportive papers about it?

If you want to believe in a personal creator God, based on your personal spiritual experiences, it's perfectly reasonable for you to do so, and you can ignore the arguments as to why there is no God, which are as flawed as the ones in favour.

But try not to be tempted into the hubris of believing that the correctness of your belief can be logically proven, and the non-believers are just too silly to see that. -

Normativity

What do you have in mind with the term 'genuine normativity'? Is it the phenomenon of somebody making normative claims - that X is true, or that people should do Y - and believes those claims to be true in some absolute, objective, mind-independent sense?I don't think it's explaining genuine normativity — Mongrel

If so, my attempt to explain that would be to observe that many people either do not agree that normative claims are a matter of convention, or they have never even thought about it, and so hold an unexamined belief that such claims relate to some sort of mind-inependent truth. -

Normativity

It seems to me that convention-following does explain normativity, but that nevertheless we cannot escape it, because language can only be understood if conventions are followed.The idea (as I understand it) is that if convention-following explained normativity, then we should be able to escape normative language......

Do you agree with that? — Mongrel -

Two features of postmodernism - unconnected?

No, I was musing about why most other people are interested in those subjects. My primary reason for loving those topics is neither instrumental nor about truth, but aesthetic. I love the beautiful patterns they make. I feel like a child lying on the grass looking at the clouds, saying 'Oooh, look at that one!'.Are you really interested in QM, GR and thermodynamics because of their instrumental value? — Marchesk

Where is Landru? I fervently agree with half he says and fervently disagree with the other half. I haven't heard from him in ages. I miss him.So you've adopted Landru's beliefs about science. *sigh* — Marchesk -

The Fool's ParadoxI give up. You appear determined to hold on to your belief regardless of all considerations. I wish you joy of it.

-

The Fool's Paradox

You don't mind if they harm you unintentionally? You would be happy to have as a friend a knife-wielding psychotic that believes he's surrounded by orcs?Any fool is a good friend because a fool will not harm you intentionally — TheMadFool

Even if that were the case, 'could be a friend' is not the same as 'is a friend', as Michael keeps pointing out and you continue to not understand.

Think of the kindest person you have heard of in this world that you have never met. Would they be a great friend if you knew them? Probably. Are they your friend? No, because you have never met them.

Really? In the trenches in the Great war, Helmut was Fritz's friend on the German side and Bill was Bob's friend on the British side. Yet Helmut and Fritz were Bill and Bob's foes and vice versa.Friends and foes are exclusive classes: No friends are foes — TheMadFool

Have you never heard the phrase 'my enemy's enemy is my friend'? It's a gross over-simplification but it should at least give you pause for thought. -

The Fool's Paradox

I don't know why you have suddenly come to believe this. But it's not correct, as Michael points out.Both 1 and 2 contradict the truths of

All fools are friends

All fools are foes — TheMadFool

If you really want to grow your understanding, you'd be better off reading carefully what people say, and thinking about it, rather than just automatically arguing against it, because you have fallen in love with an idea you had. -

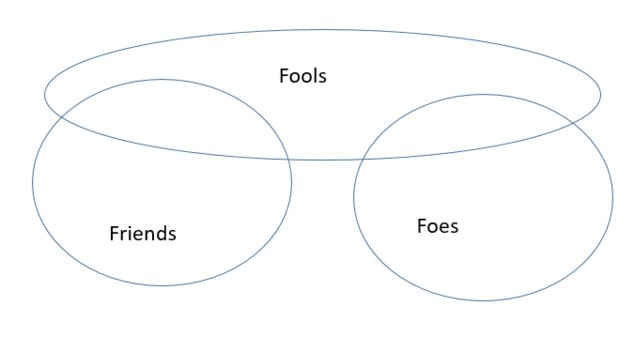

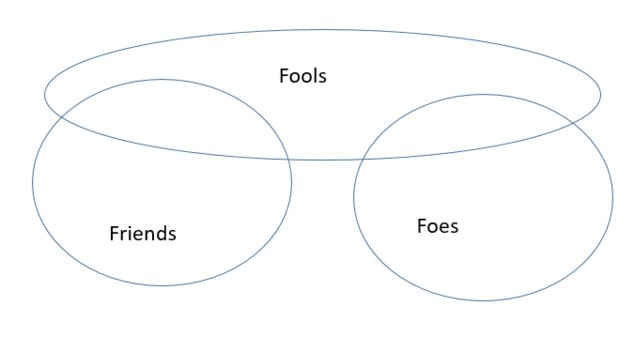

The Fool's Paradox

No, it's not. It's a Venn diagram, which is what you asked for.Note, it's not drawn in standard form re categorical logic. — TheMadFool -

Category MistakesI note that both the examples in the OP yield nicely to Russellian analysis. He would deconstruct the first one as:

1. (Claim) There exists a unique c such that c is a colour and Forall x, forall y, if x and y are both ideas then there c is the colour of x and c is the colour of y,

2. (Question) Find c.

and the second one as

1. (Claim) There exists a unique m such that m is the meaning of Life.

2. (Question) Find m.

In Russell's terms these are both 'definite descriptions', which are identifiable by the use of the word 'the' in the natural language version: 'the meaning of life' and 'the colour of ideas'.

From another perspective, they are 'loaded questions': they are a proposition followed by a question that only makes sense if the proposition is true. Russell's famous 'The present king of France is bald' deconstructs in the same way.

For the sake of advancing the discussion, I'll hypothesise that all questions that are category errors can be deconstructed in this way, to be a stapled Claim and Question. An even stronger hypothesis, of which I feel less confident, is that they all involve Definite Descriptions ('what is the X of Y?' or 'does the X Y?').

A few more examples would be good, to put that hypothesis to the test. Unfortunately my mind is a blank right now as I search for examples of category errors. I expect that searching this site for 'category error' would turn up some good examples though. -

The Fool's Paradox

Does this help?

Also, I would prefer a genius as a friend, because I see no reason to expect that the genius would use their super-powers against me, and I'd be concerned that I'd get impatient with the less-intellectually gifted alternative and be rude to them, which would upset them and me.

But maybe that's just me. -

Existence is not a predicateActually, I suppose the sentence should be

'Exists is not a predicate'

since 'exists' is grammatically a predicate and 'existence' is not.

It seems odd to say that a grammatical predicate is not a predicate. We must mean a different sort of predicate. I think we mean a logical predicate, so that the statement, at the expense of making it longer, becomes:

'Exists is a grammatical predicate but not a logical predicate.'

The way I make sense of this is to observe that when we say 'Santa Claus does not exist' what we actually mean is 'No being that ever lived had the key properties ascribed to Santa Claus'. Then in this sentence, the logical predicate is IsSantaClausLike, which means 'has all the key properties ascribed to the legendary Santa Claus' and it is formally rendered as something like:

for all x, for all t, (Alive(x,t) --> NOT IsSantaClausLike(x)) -

The Fool's Paradox

I can't see any paradox in that, nor even anything surprising.This is paradoxical. A fool suits both as a friend and as an enemy. — TheMadFool

There are many examples where a certain set-up is the best at both extremes of a linear continuum.

eg, which would you prefer to have as the sole enclosure of your body as you pass through a 200 degree oven?

(1) light underwear

(2) a heavily insulated non-combustible airtight capsule with built-in life-support systems

and what about as you pass through a minus 200 degree super-freezer?

All it demonstrates is that many relationships in the world are non-linear. -

Climate change and human activitiesYes, but you would say that wouldn't you Jorn?

You are from Denmark, and everybody knows that the Danes, with their ridiculous bicycle-based transport systems and infestations of windmills are at the forefront of the green-communist-islamist conspiracy to usurp the sanctity of the free market and the sovereignty of free nations so that we can all be made slaves to a World Government that controls our every thought and word, and saps and impurifies all of our precious bodily fluids to boot.

The only people that are more culpable than the Danes in this fiasco are the scientists. -

Meaning ParadoxLike many words, 'meaning' is a word that means different things in different contexts. Examples are:

'What do you mean?', in response to a statement that appeared to be a request or instruction, means 'I don't understand what you want me to do. Can you please explain more clearly?'

On the other hand, in response to a statement that sounded like a proposition, made in a discussion or argument, it means something like

'I didn't understand that point you just made. Can you please rephrase it to make it more likely that I can understand it?'

Then there's one of my favourites:

'I mean ....'

which means - 'I'm not confident that what I just said was intellligible, so I'll try to rephrase it to see if I can make it any more intelligible'.

In short, words don't usually have meaning. It is sentences that have meaning. And sometimes even a sentence isn't enough. One needs a whole paragraph to acquire a meaning.

The German-English dictionary that's loaded on my Kindle is very good like that. For most words it doesn't even attempt to define them in isolation. Rather, it gives several different sentences showing the different ways it can be used, and explains the meaning of each sentence. -

Reincarnation

I think it depends on what, if any, continuity, one wishes to attach to one's idea of reincarnation. If there is no practical continuity attached, in the form of memories or tangible characteristics, I think one can only make sense of the idea if one believes in Aristotelian essences. Then one can say that one's essence is the same as that of Napoleon, even though there is nothing else of note that is shared. This hypothesis is, of course, unfalsifiable.But is there a way around such objections? — Banno

If one wants to attach things like recovered memories (I remember the cannons at Austerlitz, the embrace of Josephine) then one might not have to be an Essentialist. But recovered-memory ideas of reincarnation do seem pretty kooky to most of us.

If we discard the notion of the self, like Nagarjuna or Hume, then we can get an idea of reincarnation along the lines that it is simply life or consciousness - the totality of all alive or conscious beings - that goes on. A bit Circle-Of-Life ish, perhaps a bit hippy, but not nearly as woo as 'Reincarnation' usually seems. -

Fun Programming QuizzesThrowing ALL consideration for efficiency out of the window, there is a more concise coding using recursion. Here it is in R:

This is 101 non-blank characters, compared to 204 non-blank chars in the one above. Part, if not all, of that reduction comes from the fact that R does not require declaration of variables, and printout of the value of an expression is automatic, thereby removing the need for a print statement.(findprime<-function(x,n) if (sum(x %% 1:x == 0)<3) if (n>1) findprime(x+1,n-1) else x else findprime(x+1,n) )(2,10001)

Depending on how the recursion is implemented, the code may generate a stack overflow. Mine worked OK for the 101st prime but complained about over-deep nesting in the search for the 1001st prime.

If I could remember LISP I'd try to write it in that, as that enables concise recursive expression. -

Fun Programming Quizzes

The array processing paradigm of R (and other, older languages like APL) allows for compact coding of such problems. Here's an R coding that spits out the answer:If we list all the natural numbers below 10 that are multiples of 3 or 5, we get 3, 5, 6 and 9. The sum of these multiples is 23.

Find the sum of all the multiples of 3 or 5 below 1000.

sum((x<-1:1000)[x %% 3 ==0 | x %% 5 == 0)

The %% symbol is for the 'mod' operation and '|' means OR. -

Formalization of CausationAs Sophisticat points out, as soon as we start considering counterfactuals, we get into the devil of a mess. And counterfactuals is what's going on when we write 'if (something that we have observed to have happened) were not the case, then ....'

A less troubled approach is to define cause in terms of agreed initial conditions and scientific theories. Try reading this for an approach that does it that way. -

The elephant in the room: Progress

For those of us who are not scholars of the Enlightenment, but just celebrate it and enjoy reading Hume, Paine and Voltaire, where is this 'Doctrine of Progress' specified, in order that we may read it and decide whether to assent to it or not. I cannot recall encountering it in Candide.Every scholar I have encountered who is looking at the Enlightenment and modernity says that a central feature of theirs is belief in science, reason, free markets, democracy, etc. yielding ever-increasing freedom, material well-being, etc. It is better known as progress, the Idea of Progress, the doctrine of progress, etc. — WISDOMfromPO-MO

If we withhold our assent, does that mean we are no longer allowed to agree with Hume (or whoever else our favourite Enlightenment thinker may be)? -

Fitch's paradox of KnowabilityOh frabjous day, calloo, Callay - I have found it!

Here is the nice clear demonstration that I knew I had read, but could not find, of how unconstrained second-order logic is inconsistent. I highly recommend it.

The relevance to this thread is that, since unconstrained 2nd-order logic is inconsistent, ANY proposition can be proven in that system, and so can its negation (by the Principle of Explosion - cf Bertrand Russell's proof that he is the Pope).

Hence, since Fitch's Paradox uses unconstrained 2nd-order logic, with some modal quantifiers thrown in, we can conclude nothing meaningful from any contradiction it may derive. -

The elephant in the room: Progress

I am a big fan of many enlightenment thinkers, and am tremendously glad that the Enlightenment happened.the Enlightenment progress narrative is false, delusional, dangerous — WISDOMfromPO-MO

But I have no idea what 'The Enlightenment progress narrative' is. It's certainly not a phrase that I ever use. So I don't mind what nasty things people say about it. For all I know it could be a new super-virus. -

Fitch's paradox of Knowability

What makes you you think that?The issue of the infinitely long decimal line is actually finite. — WillowOfDarkness

Here is the proposition that states the decimal expansion of e.

sum (k=1 to infinity) 1/k! = 2 + 7 * 10^-1 + 1 * 10^-2 + 7 * 10^-3 + 2 * 10^-4 + ........

the sum of terms on the RHS goes on forever, and cannot be condensed. -

Fitch's paradox of KnowabilityOn the contrary, it is precisely because I agree with that, that I see the set of propositions as containing exactly half true ones and half false ones (being the negations of the trues ones).

I suspect we must be at cross purposes here. -

Fitch's paradox of KnowabilityWouldn't it be half the set of propositions, since half are true and half are false?

-

Fitch's paradox of Knowability

That isn't my reason. My reason, which I did give, is that my observation is that most people use the phrase 'a truth' in that way and, in order to facilitate communication with others, I adopted what I judged to be their practice.I was wondering whether your reason for counting truths as a subset of propositions is that there are both true and false propositions — John

But if it helps advance the discussion - which I am finding jolly interesting - we can assume for the sake of argument that I accept the reason you gave (which sounds OK to me) and see where it leads us. -

Fitch's paradox of Knowability

I expect there are truths that no human could ever know, because even the statement of the truth is too long to be held in a human brain. Further, for any organism of limited size, be it ever so much brainier than humans, there will be truths long and complex enough that the same restriction applies to them, just farther down the road.To extend it then, are there truths which can never be known? — John

As to whether there are exists a truth T such that we cannot imagine any finite organism - be it as large and brainy as we wish to imagine it - ever being able to understand it, I don't currently have an opinion on that.

But ... (thinks) ... what about truths that contain an infinite amount of information? For instance, consider the infinitely-long proposition that states that the decimal expansion of Pi is <insert here the infinitely long decimal expansion>. IF we count that as a truth - contrary to the usual convention that propositions must have finite length - then it is a truth that no finite organism can know.

If there's a God, then it can know it. Do we count God?

That is simply my understanding of how the word is used. If there is a significant group of people that use it in some other way, I have yet to encounter them.Also, would you be able to explain why you think that truths are a subset of propositions? — John

I know Farrell Williams says 'Happiness is a Truth', but I think he is speaking poetically, not literally. :D -

Fitch's paradox of KnowabilityYes, that seems to follow.

It is possible that my interpretation of 'there are' in that sentence may be different from that of a hard-core Realist, but let's leave that aside for the moment, as it may not be important to the discussion. -

The elephant in the room: Progress

Yes. I could too, but I don't see that that amounts to a mound of beans.I am not armed with evidence right now, but I bet if I had the time and other resources I could find a lot of evidence of horrible things done in the name of "progress — WISDOMfromPO-MO

Somebody doing something harmful 'in the name of X' is no reason at all for anybody else to remove X from their aspirations.

What matters most is what is done, not what people say it is done 'in the name of'.

What are you actually trying to argue? Are you just saying you don't like people using the word 'progress'? Or are you saying that people should not try to improve the lot of their fellow creatures? -

Fitch's paradox of Knowability

My understanding and, I would venture to guess, the understanding of the person in the street, is that the set of all truths is a subset of the set of all propositions.The KP principle can be formulated as a claim about all truths (as it appears in the Stanford article) rather then all propositions — Fafner

Put simply: a pebble cannot be a truth, but the statement 'The object in my hand is a pebble' can.

So I can't see how framing the purported proof in terms of truths rather than propositions can help it to succeed. -

The elephant in the room: Progress

Progress is relative. We aim to make things better in the foreseeable future than they are now, and to maintain the improvements we have over the past.Would your worldview, philosophy, etc. implode if progress is an erroneous idea? — WISDOMfromPO-MO

Sometimes we fail. That's life. It's not a reason not to try, else nobody would ever try to do anything.

From time to time civilisations may collapse, and periods of bloody anarchy ensue. That's life too. But again not a reason not to do anything. And from the desperate low point of that anarchy, perhaps civilisation will one day again start to emerge - relative progress.

And in the end the universe will die a long slow heat death.

But if we do our best to be kind to one another in the meantime, perhaps there will be more happiness and less misery across the broad sweep of spacetime then there would otherwise have been. -

Fitch's paradox of Knowability

Sure. That's why I'm pointing out that the problem doesn't exist in natural language, because the proof is written in formal language. This isn't a case of a natural language statement that we all believe being unfairly torn down by formalism. It's a case of an attempt by Fitch to formally prove a natural language statement that nobody believes. So it is entirely pertinent to point out that the purported formal proof is syntactically invalid.My point is simply that if you solve a certain problem in a constructed formal language, it doesn't by itself prove that you've solved the problem as it exists in natural language. — Fafner

It's Fitch that chose to play by the rules of formal languages, not me.

If there's a natural language version of the purported proof, that a non-philosopher would accept as credible, we can discuss that but, so far as I'm aware, there isn't.

So, as far as I can see, there is no natural language problem to be solved.

It's a variable, because it's written Kp, preceded by a universal quantifier over p.And how do you think 'P' is treated in the formulation of the paradox (say in the Stanford article) as a constant or a variable? — Fafner -

Fitch's paradox of KnowabilityI assume you are referring to this:

That post omits the most controversial part, which is the assertion that all truths are knowable, so the post being simple does not mean that the purported proof as a whole is simple.

At most, the post proves that IF we know Q then we know P. But it does nothing to convince us that we do know Q.KP seems like a perfectly consistent thing to say — Fafner -

Fitch's paradox of Knowability

Sure, we can interpret a sentence to mean whatever we want it to mean. Thus, we can make sense of the famously uninterpretable sentence 'This sentence is false' by just interpreting it to mean 'Blue is a colour'. But I don't see how that is any way a useful thing to do.But there's no such thing as a theory of types, and there could be no "syntax errors" in a language (because every sentence in language can be potentially made sense of with the right interpretation). — Fafner

I don't know what 'there's no such thing as a theory of types' means in this context. Here's the one I had in mind.

That's not the way syntax rules work. Most syntax rules operate on a 'rule in' basis, not a 'rule out' basis. A positive justification is needed for a sequence of words being valid syntax - not just an absence of breaching any 'thou shalt not' laws.If you cannot put 'know' in front of every sentence then there should be a principled explanation why — Fafner

Some people may not like that, but that's the way theories of language work. Without it, we'd be sitting around agonising over why we couldn't understand the sentence

'Unquestionably brick falafel entertain under'

I might sympathise with the 'cheap trick' complaint if the syntactic objection prevented us accepting a purported theorem that was highly intuitive. In such a case it would be natural to ask - is the problem with the theorem or with our syntax rules?

But in this case the purported theorem is completely contrary to our intuitions, and the syntax rules help us to understand why (ie because it is not a theorem at all). I would see that as case closed, with complete satisfaction, and intuition vindicated.

There's no problem with that statement, provided P is a constant, not a variable.KP seems like a perfectly consistent thing to say — Fafner

The restrictions to second-order logic that are needed to prevent inconsistency do not prohibit such a statement.

But if P is a variable, inconsistency will creep in, because we can then (unless prevented by other constraints) substitute a wff S containing KP for one or more instances of P in S, thereby generating circularity and in some cases infinite regress. It is often straightforward to generate a contradiction from such constructs. -

Fitch's paradox of KnowabilityThe paradox arises from the fact that the logical language being used is unconstrained second order, and IIRC second-order logical languages are inconsistent unless subjected to some constraints.

That the language is second order can be seen from the implicit predicate in the statement

KP. For every proposition P, it is possible to know P. — Fafner

This requires the existence of a unary predicate Know, which can take as argument any well-formed sentence in the language.

The paradox tells us about the problems of using unconstrained second-order languages, rather than telling us anything meaningful about knowledge.

If one of the standard ways of constraining higher-order logic to retain consistency (eg Russell's theory of Types), is invoked, the paradox disappears because some of the statements in the attempted proof cannot be made - they are syntax errors. -

Why do people believe in 'God'?

I don't think many people these days would bother to contest the Son of God claim, since that claim needn't be blasphemous or controversial. When I was a young RC, we used to sing a modern hymn called 'Sons of God', about how we are just that.Jesus DID claim to not only be the Son of God, but to be one with the Father. — Agustino

To say 'I and the Father are One' goes a considerable step further, but that is only in John, which was written much later than all the other gospels, with the writer aiming, through the words he attributed to Jesus, to promote a very specific theology that there is no evidence of being in place when the earliest gospels were written. -

Why do people believe in 'God'?

Really?Don't act like you don't know what I'm talking about here and haven't ever done this sort of thing or thought in that sort of way about these sorts of people, because I don't buy that for a second. — Sapientia

Then it appears there's no hope of my persuading you towards a more open-minded view, since you know more about what I think than I do. -

Why do people believe in 'God'?

What does that mean?Crazy is crazy, now matter how you dress it up, how widespread it is, how prominent it is, and so on and so forth — Sapientia

Are you saying that anybody that believes they have been in communication with god is 'crazy' (whatever that means)? If so, you're back in the hole created by your original sneer, and still digging. -

Why do people believe in 'God'?

not very well at all.And how does that compare if you swap "God" with "extraterrestrials" — Sapientia

Firstly, because aliens are claimed to manifest physically, it defies reasonable expectations based on our scientific knowledge to believe that such manifestations would occur without being observed by others. That consideration does not apply to communications from a deity which are reported as internal psychological events, observable only to the recipient.

Secondly, claims about having been abducted by aliens tend to be made by people that typically have limited education and intelligence, not occupying positions of significant responsibility or influence. In contrast there are many highly intelligent, high-functioning people in positions of social importance that appear to believe they have a relationship with a deity. -

Why do people believe in 'God'?

What is it you want to say about evidence? We have this:The context makes it highly appropriate to talk about evidence. — Sapientia

to which the obvious answer is 'to somebody else - probably none, and so what?'What evidence is there that someone has experienced the presence of God, as opposed to having had an experience and concluded that they experienced the presence of God?

To the OP question 'why do people believe in God?', some made the reply 'because of their own internal experiences'. They have the evidence of their own senses, and nobody else does. The question of why they believe in God has been satisfactorily answered. It is only if Believer A seeks to persuade person B to adopt A's beliefs, on the basis of A's internal experiences, that the question of evidence has any relevance. Otherwise, it's off-topic.

andrewk

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum