-

The STYLE of Being and Time (Joan Stambaugh's translation)

It was Being and Nothingness that disappointed me in terms of style, though I love the ideas and themes. I actually think Nausea is occasionally truly great. That vision of the roots of the chestnut tree is something I had experienced myself (though not with nausea, just wonder).

This "surplus" of the function or the concept or the explanation is one of my favorite themes in philosophy. And this is hilarious with an edge.A movement, an event in the tiny colored world of men is only relatively absurd — in relation to the accompanying circumstances. A madman's ravings, for example, are absurd in relation to the situation in which he is, but not in relation to his own delirium. But a little while ago I made an experiment with the absolute or the absurd. This root — there was nothing in relation to which it was absurd. How can I pin it down with words? Absurd: in relation to the stones, the tufts of yellow grass, the dry mud, the tree, the sky, the green benches. Absurd, irreducible; nothing — not even a profound, secret delirium of nature could explain it. Obviously I did not know everything, I had not seen the seeds sprout, or the tree grow. But faced with this great wrinkled paw, neither ignorance nor knowledge was important: the world of explanations and reasons is not the world of existence. A circle is not absurd, it is clearly explained by the rotation of the segment of a straight line around one of its extremities. But neither does a circle exist. This root, in contrast, existed in such a way that I could not explain it. Knotty, inert, nameless, it fascinated me, filled my eyes, brought me back unceasingly to its own existence. In vain I repeated, "This is a root" — it didn't take hold any more. I saw clearly that you could not pass from its function as a root, as a suction pump, to that, to that hard and thick skin of a sea lion, to this oily, callous; stubborn look. The function explained nothing: it allowed you to understand in general what a root was, but not at all that one there. That root with its color, shape, its congealed movement, was beneath all explanation. — Sartre

Did Sartre mean to be funny? I hope he sometimes laughed as he wrote Nausea.My thought is me: that's why I can't stop. I exist because I think… and I can't stop myself from thinking. At this very moment - it's frightful - if I exist, it is because I am horrified at existing. I am the one who pulls myself from the nothingness to which I aspire. — Sartre -

What is the subject matter of philosophy?

Yes, I agree. It's the most general and therefore necessarily an abnormal or revolutionary discourse. "I think "sophistry" as its primordial ground, because you have to successfully established the rules of "logic" or "legitimate" reason within whatever discourse is most general. Thought rethinks its own essence, but that is almost to re-invent its own essence.And the fundamental claim of the book, in fact the very first statement, is that metaphysics is "the most general attempt to make sense of things." — darthbarracuda

Metaphysics is the attempt to understand the very fabric of intelligibility, the way we make sense of the world. — darthbarracuda

Nice. I agree. We posit necessary structures. Whence certainty? The beauty of the idea in our living context seduces. We live successfully as-if. No one has come along with something better yet.An analogy would be of watching a theatrical program and wondering how the various dramatic structures work behind-the-scenes; except in the case of metaphysics, we can't just sneak around the stage and observe the machinations of the playwright, because we are Beings-in-the-world, part of the world itself and thus unable to "escape" the world and view it outside of the lens of our own perceptions. The best we can do is speculate on the possibly-necessary. Indeed in the past any sort of unobservable entity in science was often said to be "metaphysical" - a possibility that was necessary for a theory to make sense. — darthbarracuda

Yes, that makes it sound more alive. We are all metaphysicians, even the illiterate, as soon as we can speak, if not before. We have "software" that can contemplate and edit itself --and can apparently contemplate this ability to contemplate and edit itself. We are self-consciously self-conscious. We can think about "unknown unknowns" in the abstract.I think the most important point of this statement is the identification of metaphysics as an attempt, and not a discipline. This loosens the definition of metaphysics, and turns it into something more akin to an anthropological drama; something that is inherently human. This coincides well with Nicholas Rescher's claim that philosophy, in particular metaphysics, is something that any rational agent inevitably does, because he has to. — darthbarracuda

I like Rescher, too. His methodological pragmatism acknowledges our loyalty to paradigms or belief-systems and not really to individual beliefs. -

What are discussions on 'what is the nature of truth?' really about?

I'm not against power structures. Politics will always be with us. Like I said, I want my religion to be beyond all that in its essence, even if it influences such things. We have different lives, different histories, different prejudices. That's what finite selves are made of. But (as I see it) we don't want to get trapped on this level. Because we are only playing the role of our opponent's shadow. We need our ideological enemy to the play the inferior role to our superior role. This game is inescapable in general, I think, but we can see beyond it with the best part of ourselves. I've always had mixed feelings about taking politics seriously. Some part of me always felt diminished and betrayed. I felt a thirst for something higher and larger-hearted than all of this grinding of oughts against oughts. I think that's why there is talk of the "beyond." Some part of us gets sick of the pettiness. Any of us can fall into a petty, stubborn defensiveness. Conservatives and progressives sneer the same sneer. They dehumanize the other, project their own repressed dark side across the aisle. I think facing one's own dark side (sex, violence, greed) is important, but then I was influenced by Jung. "Be wise as a serpent but gentle as a dove." But again, this malfunctions as duty rather than as wise counsel. (And of course this is just what the "spiritual" means to me.) -

Mysticism

I actually read I and Thou very young, probably too young -- but I always remembered that he capitalized "Cause." It stuck with me, this archetype of the sacred 'It.' It's also in Stirner, who writes from a place of savage but ultimately benevolent irony in a different context. We use these "sacred its" to exalt ourselves. (Or at least I see this general structure everywhere.)The bit about lovers seems to me to parallel Martin Buber's concept of 'Ich und du' in which he sees close personal relationships as a window into, or a path towards, a relationship with God. I've never felt that I understood very well what Buber was getting at, yet it resonates strongly with me, which is for me part of what mysticism is about. — andrewk

But, yes, the lovers! "That which is done out of love is always beyond good and evil." I realize that law and the quest for superiority by criterion X is always going to dominate mundane life, but I'm grateful that we can sometimes (the more the better) love others "authentically" --as a privilege and not a duty --and attain a state of play, freedom, sinlessness, "infinite jest" that knows nothing sacred, for it is the sacred in its warm-hearted impiety. I thought of ES and his waves. I think of Freud and his "oceanic feeling." I very much relate to something like a "rational" mysticism. It's very nice to see such left brain power and discipline married to profound "mytho-poetic" insight or intelligence.

In general the promoters of anti-mystical 'Scientism' - people like Hawking, Krauss and Dawkins - seem to me to be less impressive as scientists. — andrewk

I can't speak to their science, but Scientism is nowhere I'd want to live. Krauss misunderstood (in my view) the "why is there something rather than nothing?" question profoundly. (He seems blind to his own metaphysical enframing of this question. ) -

What are discussions on 'what is the nature of truth?' really about?

As I see it, a general structure of law and sin pervades life. Even progressives who scoff at religion themselves obsess over whether they are guilty of racism or sexism. This is their version of sin. I don't think it's different in first-person emotional terms from the experience of "old-fashioned" sin. The world is and has always been a traffic jam of law-bringers, accusers, and those guilty before their own law and the laws of others. It's a jungle of status significations, apes beating their chests, Inquisitions, class race and gender solidarities, Stalinist purges, paleo diets and crossfit as religion, etc. etc. It's the assertion of finite personality as the "true" law. The self identifies with something finite and partial and is therefore at war.

But stepping into "Christ" is stepping out of all this noise and angst and need to assert. It affirms even the endless narcissism that the jungle of finite personality is made of. It is itself clarified and opened by moves within this jungle.

So the freedom in Christ has its contrast in the mundane world, which it does not replace or obliterate. It's like a lamp that burns more or less brightly. I can reference peak experiences, but I feel the warmth and light of this image most of the time. I could deductively/defensively just call it a clump of thoughts and feeling. But that's pretty much what we are inside. So the best part of us can (in my view) very well be "just" a clump of thoughts and feeling. -

What are discussions on 'what is the nature of truth?' really about?

If I'm close to another position, all the better. I really love Hegel and the conceptual evolution of self-consciousness. Ideas can glow. We can passionately love them. So maybe we aren't so far apart. But for me there's the concept of something beyond any law or authority. Maybe it's the in-finite concept as the negation/subsumption of all finite concepts. I get something from it, and I can relate it to themes in the Gospels, but I make no claim toward its universal validity or relevance. -

What are discussions on 'what is the nature of truth?' really about?

First, I'm enjoying discussing such a grand issue!

From my perspective, the inner Christ transcends the scriptural Christ. Saint Paul has no authority over the inner Christ, even if he's one of the great poets or communicators of this Christ. For me, Christ is beyond all scripture, all laws, all sages. I quote scripture as a sort of "poetry" that points within to the primordial source of such poetry. My heretical "Christianity" is just as "at home" in Stirner and Nietzsche, because the "Luciferian" aspect of this primordial image is just as valid. For me, atheism was a valuable detour. Iconoclasm has been hugely important to me. Negative theology, too.Or rather Christ is the Law... — Agustino

If God is the totality as you say, and man is a part of that - then we cannot pretend that what must hold true of the totality also holds true of the part. For God, his intellect and his will are one and the same. Thus God cannot act contrary to the Law, which is given by his intellect. For man - who is a part of this totality, his will is separate from his intellect. Thus man's will can act contrary to his intellect. The part that is always free and always pure, as you say, that is the intellect. That's "one's best self". — Agustino

I think the intellect has a huge role to play, but I'd say that love is man's best self. But we think and love at the same time, so it's not a mindless love. I guess I envision a synthesis, the man who has organized his concepts and heart so that the world makes sense and is beautiful at the same time. But this is hard work, as you imply. In that Plato quote above, I think this is addressed. Desire and intellect inform one another. A series of frustrations (collisions of will and intellect) are like the rungs on a ladder. -

Are the present-to-hand ready-to-hand?

Perhaps, perhaps. Really I just loved those passages I quoted and whipped up a thesis to have an excuse for conversation around them. I'm no "Heidegger" expert. I can hardly enjoy reading the guy. And yet I think he has some profound ideas, having looked into a few secondary sources.

I know that my pencil becomes transparent when I'm doing math, and I think certain philosophical frameworks become transparent when we are working within them. Of course there's always something transparent and something visible. Maybe I expressed myself badly as if I didn't see this. But I think the "visible" can be frame (maybe) as unreadiness to hand. It's visible because it's being worked on or fixed. But the tools we are using to fix it are invisible. So we lose ourselves in fixing the unready. We become the unready. But the ready-to-hand or the framework we are assuming is itself invisible. Even if this is not sufficiently Heideggarian, perhaps you can relate. -

What are discussions on 'what is the nature of truth?' really about?

For me, this puts us outside of God, beneath God. Frankly, I don't have a sharp notion of God. I'm tempted to say that God is the totality, reality itself. But I can work with Christ as an image in passionate mind. The Law is beneath him, but not because he's so eager to break it. It's just a man made thing, a political tool, technology that enables community. It's only itself justified by the love and respect we can actually feel for one another. I relate to experiencing the law (or that best parts of it) as congruent with one's best self. I think Hegel addresses this. One doesn't want to steal or kill or commit adultery, or at least one's best self doesn't. But external or internal violations of the Law don't close us off from this image written on the soul of a person above everything fixed and alien to the self. -

What are discussions on 'what is the nature of truth?' really about?

Thanks for the tip. I have to be honest though and say that I can only see duty as part of the Law that "my" so-called Christ (name doesn't matter) "transcends." There's an everyday sense of duty that I relate to, of course.

As far as the lovers go, I think the eternity is always already there in the love itself, because what they love in one another is bigger than either finite personality. They both incarnate something universal or eternal. In the mystery of sex, too, we have eternity. The lovers must die, but the love does not. For me the "cross" represents the death of the finite self. We have to assent to the death of our small selves, not as a duty but as a trade for access to what is deeper and more universal or eternal in our guts. (I don't know what my heretical assimilation of the Christian tradition can mean for others. But for me it's close to the flesh and the world. It affirms the flesh and the world, which is to say death and sin.) -

Mysticism

Beautiful quote. I relate to some of that. I've experienced some of that myself. But I don't think there's a difference in quality but only a difference in the intensity of the love experienced. For me, anyway, it was just like going from 40 watts of love to 400 watts of love. And the sense that this life (my life) and this world were "perfect" and "infinite" and "holy" was also there. My theory is that this stuff is "hard wired" in our guts. We can switch it on with the help of concepts and symbols. If a person tunes in to this elevated state, it's going to have a personal stain, like light through stained glass. But the center of it seems to be the love and the affirmation of the world that once looked so broken and sinful and ugly. This is why (for me) the accusation in the name of some exterior law is a betrayal or a forgetting of the experience or insight. It's merely politics or prudence, a necessary "evil" but not at all "deep" religion. -

MysticismPersonally I prefer a stronger balance, and therefore find myself being much more an Aristotelian than a Platonist -the spiritual merely uplifts, but does not negate the worldly - and worldly things are also goods. — Agustino

We very much agree here. Render unto Caesar and Newton what is theirs. Brush your teeth. Eat well. Learn a trade or a profession. But let "faith" or "Christ" light up and lighten the mundane. -

Mysticism

I hear you. I don't want to bring some kind of law or truth on these profound matters. When I reflect on my own experience, I'm satisfied with the "just feelings and concepts" description. To be clear, these are the most beautiful concepts and feelings I know. In the image, they are embodied, of course. I see old paintings of Jesus making a sign with his hand, and I think "that painter has felt/thought the same kind of thing that I have felt/thought." It's a gleam in the eye, a foot in the ocean, the view from a mountain's peak. It informs one's daily life without obliterating it. -

Mysticism

I think it's about the harmonization or unity of a personality. It usually hurts to be of "two minds." We can, of course, divide the self into various drives, but ideally they all work together, just like our internal organs. But then I have nothing against gods plural. What religion means to me is miles above (or miles below) a resistance to polytheism. It's above/below anything and everything static and finite and solemn, but it's only "infinite" in the realm of feeling (love, humor, at-home-ness) and in the realm of concept, as the negation of every finite "idol." For me, true religion is not solemn or anxious or defensive or accusing. It's exactly the opposite. But to think that I'm trying to bring a law along the lines of "thou shalt not be solemn or anxious or defensive or accusing" is to absolutely miss the point. For me, that's the stone rolled back in front of the tomb. I don't care if artists put a crucifix in urine. Any god that fragile is bad technology. (I think "Christ" or "Lucifer" is "just" a piece of technology, like just about every damn thing in the world-- and not by any means the only technology that humans need. ) -

What are discussions on 'what is the nature of truth?' really about?

I think there's an image or persona (Christ) or symbol of radical freedom and radical at-home-ness that can be "lit up" in a person's soul. For Blake, it was the "Human Form Divine." This "king of kings" is beyond the law, above the very notion of law and sin before the law. He's the son and not the servant of God. He's on intimate terms. He has God in his blood. He loves sincerely, with the heart and flesh, not self-consciously as a duty. He affirms the world. The totality is perfect or harmonized for him. He is wise as the serpent, aware of the whore and the killer in his depths. Purity and innocence-before-the-law are in the bonfire with all of the other idols. But these idols are still necessary in the world of Caesar and Newton. To be "in Christ" (from this perspective I'm relating) is not to instantly solve the economic or the social problem. It's just dipping in to an internal ocean of love, generous pride, and freedom, which allows us a profound irony and a "grounding" in this world. We were born in the right place at the right time. What seems finite and corrupt appears "infinite and holy." I think this radical vision of Christ is resisted because of an attachment to righteousness before the Law. "We are bound by our desire to bind." We are servants of an" impossible object" because we identify with the authority of this "impossible object." It's hypocrisy to accuse this power-drive, since this would be more righteousness before a new law (Thou shalt deny your will-to-power). This too must be affirmed as part of God's reality or just God as reality.

The main thing about this vision is take "the kingdom of God is within you" at its full intensity. It doesn't even matter if there was a historical Jesus of Nazareth. It doesn't matter what's in the Gospels or any other spiritual text that may serve just as well as a pilot light. Once this internal vision is lit, everything outside is just a candle in sunlight. I can switch into an objective mode and say that it's the mask on a Jungian archetype of the Self, etc. But I don't think anyone has to share my metaphysical/scientific commitments to enjoy this image. Others have their image entangled in metaphysical beliefs, which may dim its light but does not obliterate it. To mix Hegel/Plato in with this, I'd say that we grow by using "corrosives" to clarify the "Christ" within. -

MysticismThis is a passage from Hegel which I think is particularly relevant, quoted in the book I am reading, Hegel and the Hermetic Tradition. Magee thinks Hegel uses mytho-poetic language to "encircle" or "circle around" his subjects with concrete images to gain speculative knowledge of them, rather than trying to think them in the determinate language of abstract conceptualization. So we get a picture, but no definitive propositional-type claims are made about the subject and there always remains mystery. — John

I opened the passage and thought it was great. I want to read that book. I read both Kojeve and Wittgenstein's TLP with something like a mystical or speculative feeling. "Mytho-poetic language" is exactly what I have in mind. "Symbols of transformation" also come to mind. The propositional content does not exhaust the symbolic statement. It has a resonant ambiguity. I was listening to this beautiful song last night and it occurred to me how supreme poetry set to music can be.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ch6h278GEpA -

What are discussions on 'what is the nature of truth?' really about?

The vision I'm trying to share includes a chasm between prudence and politics on one side and access to a feeling beyond all politics and sin on the other side. Like anyone these days, I keep up with the "culture war." But what I get from what might be called a "symbol of transformation" is a space in my thinking and feeling that is beyond this war. I would never deny the need for laws, nor that children must be taught to obey the rules that they cannot yet understand in their ignorance. It's just that religion must offer something beyond politics and prudence and even theology and metaphysics in my view, and I find that it does.That sin and error are necessary for the progression of an individual is undeniable. However - a society, in order to maintain the stability required for the individual's progression must contain and restrain sin. — Agustino -

What are discussions on 'what is the nature of truth?' really about?Instead of sexual intercourse, it leads to discussions about beauty and to accounts of it. — Wayfarer

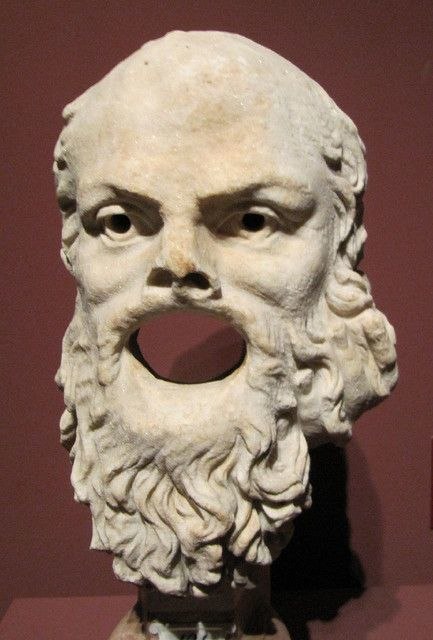

Well, the context was men and boys, and Socrates was put to death for something like sin:

As a man who loves boys in an idiosyncratic, because elenctic, way, Socrates is placed in potential conflict with the norms of a peculiar Athenian social institution, that of paiderastia—the socially regulated intercourse between an older Athenian male (erastês) and a teenage boy (erômenos, pais), through which the latter was supposed to learn virtue. And this potential, as we know, was realized with tragic consequences—in 399 BC Socrates was found guilty of corrupting the young men of Athens and condemned to death. — SEP -

What are discussions on 'what is the nature of truth?' really about?

Epicurus' 'hedonism' is not ours, though.

It must be remembered that Epicurus understood the task of philosophy first and foremost as a form of therapy for life, since philosophy that does not heal the soul is no better than medicine that cannot cure the body (Usener 1887, frag. 221). A life free of mental anxiety and open to the enjoyment of other pleasures was deemed equal to that of the gods. Indeed, it is from the gods themselves, via the simulacra that reach us from their abode, that we derive our image of blessed happiness, and prayer for the Epicureans consisted not in petitioning favors but rather in a receptivity to this vision. (Epicurus encouraged the practice of the conventional cults.) Although they held the gods to be immortal and indestructible (how this might work in a materialist universe remains unclear), human pleasure might nevertheless equal divine, since pleasure, Epicurus maintained (KD 19), is not augmented by duration (compare the idea of perfect health, which is not more perfect for lasting longer); the catastematic pleasure experienced by a human being completely free of mental distress and with no bodily pain to disturb him is at the absolute top of the scale. Nor is such pleasure difficult to achieve: it is a mark precisely of those desires that are neither natural nor necessary that they are hard to satisfy. Epicurus was famously content with little, since on such a diet a small delicacy is as good as a feast, in addition to which it is easier to achieve self-sufficiency, and “the greatest benefit of self-sufficiency is freedom.” — SEP -

What are discussions on 'what is the nature of truth?' really about?

I was looking into Plato's notion of love and was shocked to see Hegel there -- or so much of Plato in Hegel.

That underlined bit is the "Hegel." Frustration/incoherence leads up the ladder to higher forms of love. So "sin" or "error" is necessary and the desired being or highest love is not timeless but instead utterly depends on time. There's no jumping ahead of the dialectic. We live forwards but understand backwards. (Or that's how I'm seeing it.)The stories of all the other symposiasts, too, are stories of their particular loves masquerading as stories of love itself, stories about what they find beautiful masquerading as stories about what is beautiful. For Phaedrus and Pausanius, the canonical image of true love—the quintessential love story—features the right sort of older male lover and the right sort of beloved boy. For Eryximachus the image of true love is painted in the languages of his own beloved medicine and of all the other crafts and sciences. For Aristophanes it is painted in the language of comedy. For Agathon, in the loftier tones of tragedy. In ways that these men are unaware of, then, but that Plato knows, their love stories are themselves manifestations of their loves and of the inversions or perversions expressed in them. They think their stories are the truth about love, but they are really love’s delusions—“images,” as Diotima will later call them. As such, however, they are essential parts of that truth. For the power of love to engender delusive images of the beautiful is as much a part of the truth about it as its power to lead to the beautiful itself.

But because they are manifestations of our loves, not mere cool bits of theorizing, we—our deepest feelings—are invested in them. They are therefore tailor-made, in one way at least, to satisfy the Socratic sincerity condition, the demand that you say what you believe (Crito 49c11-d2, Protagoras 331c4-d1). Under the cool gaze of the elenctic eye, they are tested for consistency with other beliefs that lie just outside love’s controlling and often distorting ambit. Under such testing, a lover may be forced to say with Agathon, “I didn’t know what I was talking about in that story” (201b11–12). The love that expressed itself in his love story meets then another love: his rational desire for consistency and intelligibility; his desire to be able to tell and live a coherent story; his desire—to put it the other way around—not to be endlessly frustrated and conflicted, because he is repetitively trying to live out an incoherent love story. — http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/plato-friendship/

This is what I originally had in mind when I thought of Plato on Eros:

Great stuff...First, if the Leader leads aright, he should love one body and beget beautiful accounts there” (210a6–8). At this stage, what the boy engages in the lover is his sexual desire for physical beauty, albeit one which, in firm keeping with the norms of Athenian paiderastia, is supposedly aim-inhibited: instead of sexual intercourse, it leads to discussions about beauty and to accounts of it. Here the beauty at issue is, in the first instance, the boy who represents beauty itself to the lover. That is why, when the lover finally comes to see the beautiful itself, “beauty will no longer seem to you to be measured by gold or raiment or beautiful boys or youths, which now you look upon dumbstruck” (211d3–5). One effect of generating accounts of this beauty, however, is that the lover comes to see his beloved’s beautiful body as one among many: if it is beautiful, so are any other bodies the accounts fit. And this initially cognitive discovery leads to a conative change: “Realizing this he is established as a lover of all beautiful bodies and relaxes this excessive preoccupation with one, thinking less of it and believing it to be a small matter” (210b4–6).

...

But love that is to escape frustration cannot stop with bodies. The attempt to formulate an account of love free from puzzles and immune to elenctic refutation must lead on from beautiful bodies to beautiful souls, and so to the beautiful laws and practices that will improve souls and make young men better. Again this cognitive achievement is matched by a conative one. When the lover sees that all these beautiful things are somehow akin in the beauty, he comes to think that “bodily beauty is a small thing” (210c5–6), and so, as before, becomes less obsessed with it... — same -

The STYLE of Being and Time (Joan Stambaugh's translation)

I can say that I'm thankful for secondary sources. What others have made of Hegel or found in him has been (for me) as good as it gets. The secondary sources on Heidegger are fascinating too. Sartre was strange, because he could write enjoyable novels and plays. It's as if he became uptight or pretentious when "getting (all too) serious." My gripe with all of them is a sort of "scientism" in their style. It's depersonalized. I guess that's the physics haunting metaphysics. We must ignore the metaphorical and analogical and ambiguous. Derrida escapes this maybe, but he can be long-winded and "cute."

I don't follow Rorty all the way, but he is a stylish,radical fusion of some continental and AP philosophy. -

What are discussions on 'what is the nature of truth?' really about?

Maybe we're getting at the same thing. Duty and prohibition and innocence and haunt humanity. We are bound by our desire to bind. The impossible object still offers proximity and therefore hierarchy. This ubiquitous game (which could only be prohibited or judged from within this very game of prohibition and judgment) stifles authenticity. Even authenticity as concept can itself be taken up as a token in this game. Religion that accuses of sin against God is more or less the same thing as righteous politics that accuses of racism, sexism, etc. We can advise against and vote against fornication or discrimination in the practical realm, but religion that is "stuck" at this plane looks necessarily dead and alienated to me. It's just another hierarchy like wealth or education or looks or talent. Same old power play in terms of concepts.I think it's understood as a duty though-- for your own damn sake, you will love your lovers and friends. You will rescue your meaningless self form the ignominy of being loveless. The falsehoods of your idolatry are at least true for you. A truth which will rescue you from meaninglessness no matter how much we might understand it is falsehood. The duty to rescue yourself, "At least with my idolatry, I will have the truth which saves me." — TheWillowOfDarkness

If I understand you correctly, I agree, but I'd say that dogma is thestain of something primordial and genuine while law is its descent into guilt, accusation, purity, alienation.Every dogma or law is something primordial and genuine. A value held, a habit performed or an action sought. In this respect, it's only hidden for us in as much as we pretend it is. — TheWillowOfDarkness -

What are discussions on 'what is the nature of truth?' really about?

How about the elevation of desire? I like Plato's Symposium. I relate to an erotic element in religion. Sex is at the heart of "life-death" as opposed to "undeath." The "fire and the rose are one."Of course it sounds censorious or abstemious to speak in terms of detachment from desire, but I think it is an unfortunate necessity, because human nature, if it follows its own instincts, generally is not going to home in on existential truths of any kind. It takes effort and sacrifice, and there are simply too many distractions, too many things to pursue, no more so than today. — Wayfarer

Detachment from petty desires is great. I relate to the value in that. I suppose the danger is presenting these petty desires as bad in themselves rather than simply as obstacles or not the best that one can hope for.

I think you're ignoring something here. Political earnestness involves the suffering and projection of "protestant" guilt. We are born in sin as always, but now this is sin is racism, sexism, homophobia,etc. on the progressive side. Surely you've seen the nail-biting obsession with innocence with respect to the terrible X-isms. On the conservative side it's a mixture of sin against God, sin against Freedom, and sin against objectivity. All this "hero myth" stuff I talk is an attempt to point out a general structure. There is duty or law in the name of the (generalized) sacred and therefore (generalized) sin. And the 'sacred' I'm aiming at here is narcissism's object. Contrast genuine empathy with altruism as a duty and therefore as a right to accuse. We have un-self-conscious love for others on the one side and the enjoyment of superiority in the humiliation of sinners on the other. And the worshippers of pure reason can look down on those who make irrational or non-empirical claims. The prohibition divides humanity into an upper and lower class. Liberals have their image of the redneck racist/misogynist. IMV, then, "Christ is the end of the law" only to the degree that religion comes from a deeper place than this (necessary and forgivable) compulsive or hardwired status-seeking "instinct."As for sin - sin is the ultimately politically-incorrect word nowadays. Culture thinks it is liberated because it has ditched the idea. I wonder. I know on the Buddhist forum, one of their dogmas is that 'Buddhists don't have an idea of "sin" ' but I think that is basically because of the way it has been interpreted by the counter-culture (and also for marketing purposes, if you asked me). — Wayfarer

Religious notions of an impossible object make this Law more attractive and mysterious, but I think this gets in the way or obscures the "kingdom of God" within. Blasphemy isn't even a sin, for any "living God" in the guts is beyond such triviality. If we think of folks killing in the name of the honor of their god, the "group ego" core of the impossible object becomes apparent.

I respect that, and I respect your honesty.And I am wrestling with all these problems, I'm not preaching from a bully pulpit - I aspire to be free from selfish inclinations and cravings, because I would like to think it opens the door to a higher kind of life, but it ain't an easy thing to achieve, and there doesn't seem to be a silver bullet. — Wayfarer -

The Linguistic Limitations of Sets

Thanks!

Being is the limit concept. Everything is a being. But being has no particular content, for exactly that reason. I think consciousness is like this, at least from the first-person perspective. Being and consciousness are highly elusive! As I see it, being is also one or the one or the unit. So it's as if we were born with this "digital" or "atomic" insight for making sense of the world. All of math is built on this enclosed nothingness. But I'll stop there! I should actually do my homework.

(I jumped in because I had a hunch that you were processing totality, being, consciousness. Those are indeed the mysteries. ) -

What are discussions on 'what is the nature of truth?' really about?

I agree. It's very hard to resist beating others over the head with our idiosyncratic packaging of the "sacred." For me there is "true religion" in loving one's lover or friends. We always already have access to the transcendent as love. So (again, just for me) it's a matter of trying to live in that place of love and generosity, but not as a sort of duty. For me, this duty would be the same, old alienation. For our own damn sake we seek this state. Every dogma and every law (in my view) buries something primordial and genuine beneath 'concept religion' or idolatry (Stirner is the neglected master here). But that's just my wacky prejudice...We want to be able to say: "follow the transcendent or you will have no peace in life," to hang the threat of meaningless over anyone who would dare not follow our transcendent tradition, so they have a reason to pick us over any other activity they might do or value they might have. — TheWillowOfDarkness -

What are discussions on 'what is the nature of truth?' really about?

I like that you insist that desire is good. I think religion is often framed in terms of a set of prohibitions. Instead of virtue being its own reward, it's framed as a price that one pays (abstinence in various forms) for something higher. So religion "falls" into accusation and self-righteousness. Saint Paul isn't perfect in this regard himself, but "Christ is the end of the law" is a profound statement. I find a radical kernel in Christianity that is largely obliterated by the human tendency to create a system of law and therefore sin. Dogma also take on a "scientistic" framing. Instead of passwords toward mysterious or fundamentally emotional transformation, they are what one must believe as a good theologian. So theology becomes Christ, one might say, as the mediator of the transcendent. But then religion is just metaphysics. I read "in spirit and in truth" in terms of emotion or the "sub-rational" (also trans-rational). I think the heart (with the mind in what is actually a unity) evolves from a love of never-sinful-in-themselves things towards higher things or the transcendent or Good. The key point is that sin is just privation or clumsy desire. Prudence dictates that we make laws, cage the violent. But I think religion is best when it accuses nothing, forbids nothing, but points to the transcendent not as a duty but as an opportunity.And these are deceptions precisely because the so called object of desire they identify actually frustrates the achievement of the authentic, underlying desire - they prevent the actual object of desire from being obtained. So yes - the desire for sex is the desire for intimacy, and it is good. The desire for food is the desire for a healthy and well-nurtured body and it is good, although a lesser good than the transcendent for example, because one wants a healthy and well-nurtured body in order to be able to achieve many of the other goods. The supreme good is the transcendent though. — Agustino -

The Linguistic Limitations of SetsMy main point was if you get something that is all inclusive -whether all refers to the universal set or all refers to a specific subset that is just (I,O) - that word we use to define this all will only be definable by its parts.

And, if that is the case, this singular notion of all - universal or a subset - it really refers to something that is not singular. It in a sense becomes a failure of our language because if I was asked to define life? — saw038

I actually got into math by contemplating the idea of unity. Every thing as thing is an intelligible unity. Whatever else it has, it is wrapped up in a 'singular' concept. Look around, and you see "circles inside of circles inside of circles." The dog is a unity of its nose, tail, fur, etc. These are unities can that be broken down. The big unity, the totality from which nothing is excluded, is problematic. We can't explain it, since there's nothing outside of it to use as an explanation. Anything nice little idea we have about is instantly part of this therefore unstable totality.

You might also be interested in axiomatic set theory. Naive or purely intuitive set theory generates contradictions, so an attempt has been made to apply just enough rules so that no contradictions are easily found (though they could be hiding in there somewhere.) It's beautiful stuff. We have the ideas of containment or unity in relationship to ideas of order. All of math can be built out of a single "circle," the empty set, which is like "pure" unity itself. Being == nothingness. -

What is your philosophical obsession?

For me that's where philosophy gets exciting. Reason finally looks into itself. Demystification takes a long, hard look in the bathroom mirror. -

The STYLE of Being and Time (Joan Stambaugh's translation)

I'm starting to feel my way in. I was reading last night well into the dawn, after hours spent here. I had to slow down. He's very thorough, very patient. I think I'm going to love this book.Heidegger actually flows for me. — csalisbury -

The STYLE of Being and Time (Joan Stambaugh's translation)

Yes, I agree. I experience the "mystic" power of these myths which are therefore "true." Because it's trans-rational or sub-rational, I abandon any sort of empirical claim. Even a metaphysical claim would feel like idolatry, or the spirit dying into letter.Yes, I would even say that we are God's flesh and blood, and that the Eucharist and the Incarnation and Resurrection are all symbolic of that Holy Union. — John

I totally agree. And perhaps you can see the possibility of a more "spiritual" or "complete" pragmatism, here. One could argue that it's always our hearts and guts that finally believe. If we can meet the world more joyfully and successfully with help from (reductively, 'defensively') a "string of marks and noises," then there's some kind of "truth" in such a string. I love "rising ecstasy over dogma." In contrast, I remember hearing arguments about whether to baptize in the name of JC or in the name of the F, S,& HG. It's hard for humans to live without their legalism and formalism, but this too me just buries everything valuable. Atheism is therefore valuable, perhaps, as a cleansing fire.

For me these are not empirical propositions at all, but profound truths in a kind of (here good) pragmatic sense in that they stir the embers and stoke the fires of transformation which may lead to the utmost reverence for life. I can't see how that can be a bad thing, provided the dogma is kept in his kennel in the howling blizzard, not out of cruelty, but out of compassion, giving rein to imagination, and a rising ecstasy over dogma. (I wish there were an 'insane person' emoticon; I feel so much like using one right now). — John

It's very Freudian. He looks at (or dreams up )the tangled depths of religion, sex, and politics.I haven't heard of the Norman Brown book, but I'll check it out. — John -

Are the present-to-hand ready-to-hand?We do reason about death, but we have no determinate concepts about it, just whatever we can imagine or intuit. It thus forms a gaping hole in our concept systems, along with origin, (which in a sense is the same question) for that matter. — John

Good points. For context, I feared hellfire as a child/teen. Mom was religious. The old man was profane and obscene. Death as nothingness was liberating. And that's my sincere expectation or my faith. Eternal sleep. So it plugs into my concept system that way.

Origin, however, is more mysterious, but I can't even imagine an explanation that could dominate this mystery. "[It] is."

Yes, I agree. Truth-as-correspondence in the physical part of "manifest image" is almost unshakable. At higher levels of science, it's already breaking down. We can be said to be relating measurements to to-be-expected measurements, with metaphors like "the point mass is a little stone" to aid us. (In the same way, mathematicians can retreat to formalism as a metaphysics, but it's hard to find formal proofs without an intuition of what's going on.)When it comes to the truth of scientific theories the isomorphic nature of any purported correspondence cannot be easily, or even at all, intuited. Also, if history is a guide, no scientific theory is likely to be true in the sense of final or definitive. We can easily imagine propositions like "i did not go for a walk today' being true in a final and definitive sense, because it seems that once the day is passed the fact that I did not go for a walk during it is immutably fixed, and we cannot even begin to imagine what it could mean for it not to be so. — John

Looking at higher science and metaphysics, it's easy to see why pragmatists (and others) would look for an alternative to correspondence. -

The STYLE of Being and Time (Joan Stambaugh's translation)

Yes. Rorty got me interested in Hegel. As you may know, he wanted to abandon the mirror or lens paradigm.This relates in an interesting way to Hegel's discussion of sense perception in the PoS. He exposes the presumptions of critical philosophy that understand perception as being analogous to a glass or medium which distorts what is seen or an instrument that cannot but change what is seen when it operates upon it. — John

I agree. They are profound truths. They are radical, if taken in their full force. Not "God loves," but rather God is love or love is God. And love as the only law sounds like anarchy. So a feeling is God is the only law. Far from empirical, far from non-controversial. God lives in our guts, not even in our brain, because we ate his flesh and drank his blood. Deep stuff. Love's Body by Norman O. Brown looks into this.For me, "God is love" and "love is the only law" are anything but nonsense; rather they are profound truths, which only begin to appear as nonsense when analysis gets it sharp little ratty ontic teeth into them. It's true they are non-sense, in the sense of not being empirical statements, but the sense they have is that of a higher spiritual intuition, not that of the physical senses. — John -

Are the present-to-hand ready-to-hand?

I really don't think so. Death is huge, of course. But don't we reason with ourselves about it? I've got this candle/flame analogy. We're melting candles, but the flame is passed on. I think the highest and best in us is universal. Others will replace me. The high thoughts and feelings that light my life will light theirs. Why do I love life? I love a woman. I love philosophy. I love math. These loves will just wear a different face. Don't get me wrong. I'll take another thousand years. But there is something beautiful in laying down 'soldier' and picking up a new one. I mentioned that shrooms experience. Intense death terror, steered via Christian myth as myth into a river of love running through my chest. That was a peak experience, but this is roughly how I deal. And there's also a sense of having completed the primary mission. It may not compute for others, but I feel like I'm at the end of certain journey of once-alienated self-consciousness.Yes, but isn't death the (elephant's arse)hole in the room of the concept system? ( Phew!!! talk about mixed metaphors!!!) — John

I get that. It's very much "earth and fire." But what if one can't really make sense of correspondence at high levels of abstraction? What else is there but coherence? I think I can embrace pragmatism because I'm getting the real juice elsewhere.I confess I heartily dislike pragmatism. The pragmatist dissolves the very coherent and useful distinction between truth and belief, conflates the two. — John

I'm sustained by a sort of poetic, ironic "mysticism." It's like a negative theology. It's maybe even a heretical Christianity.

The essential feeling in all art is religious, and art is a form of religion without dogma. The feeling in art is religious, always. Whenever the soul is moved to a a certain fullness of experience, that is religion. Every sincere and genuine feeling is a religious feeling. And the point of every work of art is that it achieves a state of feeling which becomes true experience, and so is religious. Everything that puts us into connection, into vivid touch, is religious. — D H Lawrence

Well, yeah, that's part of it. James is a complicated case. But it is arguably just a twist on positivism, utilitarianism, empiricism in the light of Hegel and Darwin.I think at the heart of pragmatism is an hubristic unwillingness to admit that we cannot know the truth (in the discursive sense at least). "No truck with mystery" they seem to be crying. I see pragmatism, in this sense, as just another great leveller, no less than scientism, and in fact very much akin to it in spirit. — John

Maybe I'm not a good pragmatist in that sense, because I argue that the world is necessarily mysterious, that an explanation of the totality isn't coherent. I squeeze a negative theology out of Job. -

The STYLE of Being and Time (Joan Stambaugh's translation)

One example of metaphor would be the "mirror of nature." We can think of the philosopher as a sort of mirror or lens through which to see objective reality. But there's also metaphor as disclosure. This is the paradigm of reality made as much as it is found. So maybe a chisel works here. "God is love." Or "love is the only law." For Rorty, these statements are like "nonsense" that gets wedged in to common sense, irruptions that are gradually literalized, potentially for the community's benefit. So the philosopher is an inventor or poet, not just an undistorted mirror. -

The STYLE of Being and Time (Joan Stambaugh's translation)

I knew they were friends, but when you say 'intimate'...that would be interesting. There's also the rumor that he was a spy. -

The STYLE of Being and Time (Joan Stambaugh's translation)His Introduction To Metaphysics is one of the best examples of this I think: the first 3 or 4 chapters are lovely to read, and then all of a sudden he starts taking about Antigone and it all goes to hell. — StreetlightX

Thanks for the tip. I'll check that one out. -

The STYLE of Being and Time (Joan Stambaugh's translation)

I think you're right. The Phen. was rushed, too, if memory serves. I've read his early theological writings. They are quite clear, quite enjoyable. He also gave stirring and clear speeches, recorded in Wiedmann, if I'm spelling that right. But maybe Phen. was raw Hegel just giving birth to ideas he hadn't organized yet under a time constraint.You can have the cynical Schopenhauer view...but I think it's more likely he felt unable to express his own depth. — The Great Whatever -

What is your philosophical obsession?

That poem is deep. That little mouse is something like the truth of us, we who evolved from the nocturnal thieves of reptile eggs (or that's something I picked up long ago.) We're always warm. We don't need the sun to move. But we are hungrier than reptiles! -

Are the present-to-hand ready-to-hand?

That's where Kojeve and pragmatism start to blend. The "wise man" is satisfied. He scans the completed circle of his concept system and finds no gaps, no holes. His life doesn't contradict his theory (the real is rational is real). For pragmatism, inquiry ceases when the machine starts up again. The system of non-empirical propositions is ultimately justified by "irrational" pleasure or satisfaction or flow.

Hoo

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum