-

The Mind-Created WorldSo the observer plays an absolutely crucial role in this respect. Linde expresses it graphically: 'thus we see that without introducing an observer, we have a dead universe, which does not evolve in time', and, 'we are together, the Universe and us. The moment you say the Universe exists without any observers, I cannot make any sense out of that. I cannot imagine a consistent theory of everything that ignores consciousness...in the absence of observers, our universe is dead' — Paul Davies, The Goldilocks Enigma: Why is the Universe Just Right for Life, p 271

I tend to agree, but there's a reason I avoid the word 'consciousness.' I really think the way to go here is a kind of monism. It's not that consciousness is one of two necessary ingredients, the other being proto-stuff (thing-in-itself batter.) No. I say so-called consciousness is being pure and simple. The 'pure witness' is no longer more subject than object, even if we find it at the center of an empirical subject, which is to say intensely entangled with sentient flesh. We have something non-dual that's intimately associated with an empirical subject. And world-streaming is care-structured, hence the naturalness of 'transcendental ego' talk. But this will tempt us to stop short of identifying being and consciousness. -

The Mind-Created WorldAnyone who supposes that if all the perceiving subjects were removed from the world then the objects, as we have any conception of them, could continue in existence all by themselves has radically failed to understand what objects are. — Schopenhauer’s Philosophy, Bryan Magee

:up:

This is in line with my view, and J S Mill's and Berkeley's, I think. Objects 'are' possible and actual experiences. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismI don't see it as a metaphysical question, but a phenomenological one. It is a phenomenological fact that metaphysical questions are undecidable. The alternative would be to collapse metaphysics into phenomenology; in some respects, both Kant and Heidegger do this, but then metaphysics is no longer metaphysics, as traditionally conceived, and we have lost a valid distinction between avenues of investigation. — Janus

I hear you, but for me there's no sharp boundary. My own phenomenology-inspired view rejects the idea that reality is hidden somehow 'outside' of a so-called subjectivity that is thought of as 'inside.'

Some think of phenomenology in terms of a study of this inside without a concern for the outside (and they have reasons for doing so), but this misses what I take to be its deepest insight --- that that inside/outside distinction is a kind of prejudice or habit which has only practical justification, if that --- arguably a misinterpretation of physical science, thinking the image is the core of reality rather than icing on top. Mach makes a similar point, without calling it phenomenology. -

The Mind-Created WorldI've always thought that the designation of humans as 'beings' carries that implication. — Wayfarer

When I read (for instance) Husserl's Ideas II (which is thought to have inspired Heidegger in a pretty direct way), it made me remember the way I understood life when I was younger. The vivid sensuality of youth makes it hard to forget embodiment and perspective. But we are trained into an undeniably practically powerful tradition of taking objects radically independently.

This is so much the case that we talk of the hard problem of consciousness. We somehow find it obvious that [today's version of ] atoms-&-void can exist unproblematically prior-to-us and independently in some fundamental way.

This is despite the fact that all of our experience features our own sentient flesh continually at the center of the world. Of course I see the bodies of others as objects in the world, but the deepest part of the other, the true radical otherness of the other, is that they are also the very being of the world, the same world from another point of view. Interpentrating worldstreamings. The body of the other is a kind of avatar or vessel for some strange perspectival worlding of the world. Very strange and yet so familiar. Many many quasi-copies of the world with no original. -

The Mind-Created WorldBut the way I have worded the OP, I'm trying to avoid the implication of non-perceived objects ceasing to exist, so as to avoid the necessity of positing a 'Divine Intellect' which maintains them in existence (per Berkeley). — Wayfarer

I think this is solved with J S Mill's permanent possibilities of perception. It's a semantic twist, really. The point is that what we mean by the existence of the independent object is that it's there if we look for it, etc. If X, then Y. The bullet can kill me even if I don't want it to. If I die, my children can still live in this house. And so on. Possible and actual experience. What else is such 'existence' supposed to mean ? And what about ancestral objects ? If I had a time machine, I could look at the dinosaurs. That sort of thing, even if I can't have a time machine. Sort of like science being at least in principle testable, even if there's not currently enough energy for an experiment. I'd say reality is at least in principle experiencable (which we might speak of as present experience in terms of actuality and possibility.) -

The Mind-Created WorldThat's pretty well what I'm also rejecting. — Wayfarer

Well I think my own view (and Husserl's) is very close to a certain side of Kant --- that part in the CPR where he writes about beings on the moon.

But what is the thing-in-itself if not a transformation of the traditional atoms-and-void into something darker and more elusive ? Something radically aperspectival ? Even time and space are made part of the curtain that hides Reality from us. A gulf or moat that is declared eternally uncrossable in principle. Anti-experiential, anti-perspectival. Basically non-sense in the sense of anti-sense or pure negation of experience.

I quote Locke and Hobbes to show that Kant is very much part of a sequence, pushing things to the limit, until Fichte and Hegel went all the way, returning to a now sophisticated (direct) realism. Objects do not hide behind themselves. The subject and the object are one. -

The Mind-Created WorldSo, saying that stuff cannot exist without a perspective, to my way of thinking, conflates existence with cognition. I see no reason to do that, and it just seems logically and conceptually wrong. — Janus

All of our 'experience' of the world features it surrounding our sentient flesh. But we tend to look right through our own looking. Russell writes of a crowd seeing an event and then hardly noticing that they saw the event from this or that position, unless that position happens to be relevant. We are such practical, linguistic creatures, then we [ tend ] to 'look right through.' And physical science is a supreme achievement in this direction. But this immense convenience tempts us into paradox.

We pretend that we can mean more by 'physical object' than something like a permanent possibility of perception. I think that the nearest mountain will survive me (of course), but what that means is that I expect others to be able to perceive that mountain, after I'm gone, pretty much they way I did, when I was still around. Part of the experience of such objects is a sense of their being-experiencable-by-others.

I see no reason to do that, and it just seems logically and conceptually wrong.

FWIW, I realize it's a bold position, but 'just seems' is only a report of an initial reaction. It doesn't show how the position is wrong. -

The Mind-Created WorldIt surprises me that you say you challenge scientific realism; that seems inconsistent with your own avowed direct realism. What do you understand scientific realism to consist in, and on what grounds do you challenge it. — Janus

What I mean by such realism (the kind I reject) is the postulation of 'aperspectival stuff' being primary in some sense, existing in contrast to ( and prior to ) mind or consciousness.

Metaphysically, realism is committed to the mind-independent existence of the world investigated by the sciences. This idea is best clarified in contrast with positions that deny it. For instance, it is denied by any position that falls under the traditional heading of “idealism”, including some forms of phenomenology, according to which there is no world external to and thus independent of the mind.

I think you can find a good version of this in Hobbes.

For Hobbes, matter is 'out there' in motion whether or not anyone is 'rubbed' by it so that sensation and fancy result. Dualism, right ?The cause of Sense, is the Externall Body, or Object, which presseth the organ proper to each Sense, either immediatly, as in the Tast and Touch; or mediately, as in Seeing, Hearing, and Smelling: which pressure, by the mediation of Nerves, and other strings, and membranes of the body, continued inwards to the Brain, and Heart, causeth there a resistance, or counter-pressure, or endeavour of the heart, to deliver it self: which endeavour because Outward, seemeth to be some matter without. And this Seeming, or Fancy, is that which men call sense; and consisteth, as to the Eye, in a Light, or Colour Figured; To the Eare, in a Sound; To the Nostrill, in an Odour; To the Tongue and Palat, in a Savour; and to the rest of the body, in Heat, Cold, Hardnesse, Softnesse, and such other qualities, as we discern by Feeling. All which qualities called Sensible, are in the object that causeth them, but so many several motions of the matter, by which it presseth our organs diversly. Neither in us that are pressed, are they anything els, but divers motions; (for motion, produceth nothing but motion.) But their apparence to us is Fancy, the same waking, that dreaming. And as pressing, rubbing, or striking the Eye, makes us fancy a light; and pressing the Eare, produceth a dinne; so do the bodies also we see, or hear, produce the same by their strong, though unobserved action, For if those Colours, and Sounds, were in the Bodies, or Objects that cause them, they could not bee severed from them, as by glasses, and in Ecchoes by reflection, wee see they are; where we know the thing we see, is in one place; the apparence, in another. And though at some certain distance, the reall, and very object seem invested with the fancy it begets in us; Yet still the object is one thing, the image or fancy is another. So that Sense in all cases, is nothing els but originall fancy, caused (as I have said) by the pressure, that is, by the motion, of externall things upon our Eyes, Eares, and other organs thereunto ordained. — Hobbes

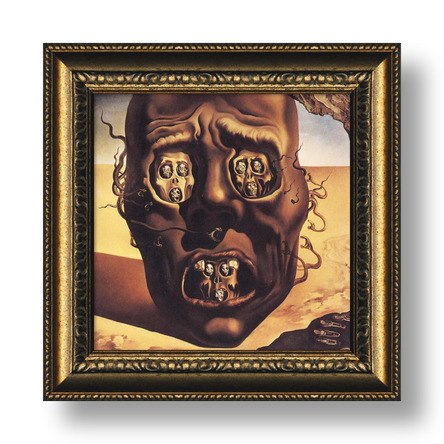

You might think that I'm a dualist, but the whole point for me is a monist clarification, which is already right there in the TLP. I am my world. The deepest subjectivity is being itself. Ontological cubism. So-called consciousness is just the being of the world given 'perspectively ' ( the being of the world is arranged around sentient flesh as a kind of origin of a perspectival coordinate system .) [It's like a cubist painting, hinted at in Leibniz and that passage about the bridge. The bridge only exists from various perspectives. ] -

The Mind-Created World

I do understand what you are getting at. I think it's a reasonable concern. We already know, using our reasoning, that some animals have better or different than senses than we do. I grant that point. And I'd say that the sentience of those creatures 'is' also the being of the world. But those creatures exist for us, and we speak of them and not their representations or surrogates. But we experience them, from or through our human perspective. And they experience us.

Perhaps we'll even agree if you see that my perspective metaphor is just that ---inspired by the visual situation but suggesting more. To see the object in a different way (from a difference place or nervous system) is still to see the object and not some mediating image. -

The Mind-Created WorldTo me you seem to be misunderstanding the idea that objects are not necessarily merely the sum of their attributes. We only know of objects, the attributes that are accessible to our human cognition. The same goes for other species. But there may be completely unknowable dimensions of objects. — Janus

I understand the temptation to say there may be completely unknowable dimensions of objects, but I'm asking what kind of meaning can be given to such a claim. It's not only unfalsifiable, it's impossible to parse at all. In my view, any attempt to give such a claim meaning will involve connecting it to possible experience. -

The Mind-Created World

That may apply to some objections to Kant, but it's very much beside the point here. I've explicitly challenged scientific realism, embraced correlationism, gone the whole Hegelian hog.Kant calls into question the 'the inborn realism which arises from the original disposition of the intellect'. That is why it produces such hostile reactions - it challenges our view of reality. — Wayfarer -

The Mind-Created World

I don't think you are seeing the issue. Kant's radicality makes the brain itself a mere piece of appearance, not to be trusted. He saws off the branch he's sitting on. Hoffman does the same thing. But it's such an exciting story.In our case, as physical beings, the brain is the vehicle of the mind, is it not? — Wayfarer -

The Mind-Created WorldWhereas I think he's right. As I've said throughout, how can there be time without duration, space without distance, and either of those without perspective? The mind provides the perspective and scale within which time and space are meaningful. That's also shown up in cosmology. — Wayfarer

If you follow me and understand 'mind' as just the being of the world, then maybe I'll agree with you, for I think space and time are as real as anything can be. But if you insist on tying mind down to the brain, then you seem to be attributing the creation of time and space to a spatial and temporal object (this same brain.) You are basically (at least implicitly) making time and space a dream, as if dreams can have meaning apart from ordinary temporal spatial worldly experience. Do you see the issue ? Kant casts into doubt all of our basic, ordinary understanding. -

The Mind-Created WorldI'll add a quote from Husserl too, because I think it's the 'temporal horizon' of objects that tempts us to project something that hides behind them. I can only see the puppy from this or that side at any given instant, but I'm still seeing the puppy, not some representative of or surrogate for of the puppy.

I claim that all we can mean when we talk of the existence of this puppy is caught up in actual and possible experience, but I further claim that this experience is really just the being of the world, which 'just happens' to reliably organize itself around sentient and sapient flesh, 'into' which it flows.

The thing is given in experiences, and yet, it is not given; that is to say, the experience of it is givenness through presentations, through “appearings.” Each particular experience and similarly each connected, eventually closed sequence of experiences gives the experienced object in an essentially incomplete appearing, which is one-sided, many-sided, yet not all-sided, in accordance with everything that the thing “is.” Complete experience is something infinite. To require a complete experience of an object through an eventually closed act or, what amounts to the same thing, an eventually closed sequence of perceptions, which would intend the thing in a complete, definitive, and conclusive way is an absurdity; it is to require something which the essence of experience excludes. -

The Mind-Created World

I hope you all find this quote from Sartre, basically the opening of Being and Nothingness, relevant (tho maybe all will have a different use or reaction).

MODERN thought has realized considerable progress by reducing the existent to the series of appearances which manifest it. Its aim was to overcome a certain number of dualisms which have embarrassed philosophy and to replace them by the monism of the phenomenon. Has the attempt been successful? In the first place we certainly thus get rid of that dualism which in the existent opposes interior to exterior. There is no longer an exterior for the existent if one means by that a superficial covering which hides from sight the true nature of the object. And this true nature in turn, if it is to be the secret reality of the thing, which one can have a presentiment of or which one can suppose but can never reach because it is the "interior" of the object under consideration---this nature no longer exists. The appearances which manifest the existent are neither interior nor exterior; they are all equal, they all refer to other appearances, and none of them is privileged. ...The obvious conclusion is that the dualism of being and appearance is no longer entitled to any legal status within philosophy. The appearance refers to the total series of appearances and not to a hidden reality which could drain to itself all the being of the existent. And the appearance for its part is not an inconsistent manifestation of this being. To the extent that men had believed in noumenal realities, they have presented appearance as a pure negative. It was "that which is not being"; it had no other being than that of illusion and error. ... But if we once get away from what Nietzsche called "the illusion of worlds-behind-the-scene," and if we no longer believe in the being-behind-the-appearance, then the appearance becomes full positivity; its essence is an "appearing" which is no longer opposed to being but on the contrary is the measure of it. For the being of an existent is exactly what it appears.

...

Thus we arrive at the idea of the phenomenon such as we can find, for example in the "phenomenology" of Husserl or of Heidegger --- the phenomenon or the relative-absolute. Relative the phenomenon remains, for "to appear" supposes in essence somebody to whom to appear. But it does not have the double relativity of Kant's Erscheinung. It does not point over its shoulder to a true being which would be, for it, absolute. What it is, it is absolutely, for it reveals itself as it is. .. The appearance does not hide the essence, it reveals it; it is the essence. The essence of an existent is no longer a property sunk in the cavity of this existent; it is the manifest law which presides over the succession of its appearances, it is the principle of the series. -

The Mind-Created WorldAs you say there are perhaps an infinite number of possible "adumbrations" of any object. But it does not follow that these transcendental objects which appear to us do not exist, or that they are not more than the totality of their possible adumbrations. — Janus

My point is perhaps best understood as semantic. Let P be claim that objects exist as more than their possible adumbrations (in a wide metaphorical sense of adumbration, which might include the inexhaustibility of the concept of a prime number.) Now what is P supposed to mean ?

In my view, the point is to see that the object is not hidden behind or within itself. It's just we are temporal beings, grasping the objects over time, seeing this aspect and then perhaps that one.

As I understand it Kant posits things in themselves because of the absurdity that would be involved in saying that something appears, but that there is nothing that appears. — Janus

I think he makes that point too somewhere (I tried to find it), but perhaps its best to understand him as the radicalization of a tradition.

Long before Locke's time, but assuredly since him, it has been generally assumed and granted without detriment to the actual existence of external things, that many of their predicates may be said to belong not to the things in themselves, but to their appearances, and to have no proper existence outside our representation. Heat, color, and taste, for instance, are of this kind. Now, if I go farther, and for weighty reasons rank as mere appearances the remaining qualities of bodies also, which are called primary, such as extension, place, and in general space, with all that which belongs to it (impenetrability or materiality, space, etc.)—no one in the least can adduce the reason of its being inadmissible. — Kant

Kant's final claim is recklessly wrong. If space and time are only on the side of appearance, we no longer have a reason trust the naive vision of a world mediated by sense organs in the first place. Crack open your Descartes, and you'll find a detailed analysis of vision and other surprisingly sophisticated discussions of the nervous system. Locke and Hobbes also acknowledged spatial and temporal reality of the brain that they needed, after all, to tell the rest of their story, the one about it 'painting' a 'gray' world of primary qualities with lovely secondary qualities, like color, sound, value, significance.

Kant makes all of that appearance, leaving nothing behind but a pointless shadow, because he thinks the grammar requires it, and because he's afraid of being seen as Berkeley --- probably because he's more absurd than Berkeley, though apparently more theologically sophisticated. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismI don't nee to work hard to justify what I said. I was agreeing with just about every philosopher who ever lived. It is simply a fact that metaphysical questions are undecidable. This is the reason such questions are called antinomies. There's nothing mysterious about it and it's common knowledge. . . . — FrancisRay

This is not a philosophical way of doing business. I think for now we should take a break in the conversation. But no hard feelings. I just think it'll be counterproductive to proceed, given our apparently very different conceptions of what kind of conversation this forum is for. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismI feel the phrase 'atemporal structure is an oxymoron. How can one have a structure without time? — FrancisRay

I'm not the one who denies time. Indeed, I'm insisted that being is time in some sense. I write of 'interpenetrating worldstreamings.' In this context, structure is something constant in the flux. For instance, physicists once talked of the conservation of energy. Or there's the tripartite 'care structure' of the stretch moment mentioned above, inspired by Husserl and Heidegger. So one can, in my view, have nothing at all without time.

But philosophers often sketch what stays the same through various changes, such as the shape of a river whose water is never the same (though of course this shape is only relatively stable.) The supreme and classic examples of timeless structure are of course mathematical. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / Phenomenalism

Not disagreeing, but Why ? Note that 'fundamental' is a metaphor that gestures to the ground, the soil, that upon which everything stands, typically unmoving, which is how we experience the earth beneath us, tho we know it hurtles through space.A fundamental theory must reduce space-time, motion and change. — FrancisRay

I'm saying that the metaphor betrays the assumption of or instinct toward that which is unchanging, that which is static in the flux. Presumably this is connect with our flesh and its needs. We want fruit that doesn't go rotten. We don't want to rely on things which are subject to moths and rust. We flee death via an identification with the relatively immortal: the eternal truth, the eternal insight, the perennial philosophy. Note that I to seek durable (relatively atemporal) knowledge, but I take this to be one more thing worth explaining. Granted that I find myself seeking such knowledge, why do I (why do we) do so ? -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismHeraclitus points out that in the world of time there is constant change but does not suggest this is the fundamental nature of reality. Heraclitus and Parmenides are easy to reconcile. . — FrancisRay

We only have fragments to go on, and of course we don't take (at least I don't take) any jaw-flapping human for an authority, but there's this:

This world-order [kosmos], the same of all, no god nor man did create, but it ever was and is and will be: everliving fire, kindling in measures and being quenched in measures.

It is simply a fact. All selective conclusions about the world as a whole are undecidable. This is demonstrable and old news. Figuring out what it implies for the world is the entire secret of metaphysics. — FrancisRay

Not trying to be difficult, but the expectation in a context like ours is that one justify grand claims of that nature. I readily grant that adopting the role of the critical-discursive philosopher in the first place is optional. Most of us here live in free societies where the problem is people being too bored with the spiritual babble of strangers to be offended by anything more than the buttonholing itself, with the incommodious proselytizing form rather than the content. Those who know It are looking for peers rather than students: they want to enjoy the wealth of the situation with others. The desire for students is still too grasping. For me knowing 'It' doesn't involve some definite content but a general sense of freedom and a kind of playful ground state. I can 'basically understand life' without even being done improving myself and learning. -

The Mind-Created WorldI meant you are stipulating that the sense of the term "existence" should be restricted to "exists for us". — Janus

I claim that we can only talk sensibly about something at least possibly experienceable by us. I'm saying connected to our experience, not fully and finally or even mostly given, for even everyday objects are 'transcendent' in the Husserlian sense: they suggest an infinity of possible adumbrations. Note that I think a person can be alone with an experience --- be the only person who sees or knows an entity. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / Phenomenalismit is at every moment relating to a new object (its own changing sense of non-objectifying awareness of the arising and passing away of temporary forms), and being affected, disturbed, by it. Disturbance, desire and dislocating becoming is prior to, that is, implicit but not noticed in ‘neutral' compassionate awareness. — Joshs

That sounds right to me, tho I don't claim to be an expert on such matters. I do think life is noisy, muddy, and wobbly, even if we can smooth it over. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / Phenomenalism

I don't go out of my way to meditate, but I can report of my happy and at-ease states, which are fortunately pretty regular, that there's a leaping from stone to stone. So it's maybe that lack of stickiness or viscosity that matters. Or what a beatnik would call a hang-up. Again I roll in Hobbes.But this thinking all rests on the supposition of a purely ‘neutral’ attention that can be separated off from any intentional objects being attended to. But there is no such thing as neutral attention. To attend to something is already to intend it, to desire, to will. Attending is a biasing. — Joshs

Continual Successe in obtaining those things which a man from time to time desireth, that is to say, continual prospering, is that men call FELICITY; I mean the Felicity of this life. For there is no such thing as perpetual Tranquillity of mind, while we live here; because Life itself is but Motion, and can never be without Desire, nor without Feare, no more than without Sense.

It's almost like a melody, with a new note born to make up for the last note dying. Sartre writes about this in Nausea, with his redheaded hero listening to jazz, learning to let the notes die, so that that music can go on, seemingly a metaphor for life itself, which one must live by continually dying. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismNon-judgemental , non-intending bare awareness of being is connected with the feeling of unconditional, intrinsic, spontaneous compassion and benevolence, peace and fundamental warmth toward the phenomenal world, concern for the welfare of others beyond mere naive compassion, joy and of the mind, etc, and this is a kind of auto-affection or self-luminosity. — Joshs

:up:

That sounds right. I like Rahula's What The Buddha Taught, and I imagine the state you describe as the goal. This is a kind of auto-affection or self-luminosity. Feuerbach also, in his own words, sees and says this. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismThe eternal recurrence of the same is the supreme triumph of the metaphysics of the will that eternally wills its own willing.

I've looked into that book recently. Of course Heidegger is famously eccentric in his grasp of Nietzsche, but there is something to be said for even a semi-fictional Heidegger's Nietzsche as the prophet of eternal return. It's a truly glorious & disturbing myth. Close to Vico, and dear it seems to Joyce. The wheel is an ancient and profound symbol, and I think Nietzsche taps into that. He also forged something that's like a stone and a river at the same time. -

A very basic take on Godel's Incompleteness TheoremI love those symbols. They are an integral part of exploring an obscure path of conceptualization and discovery. It's all about exploration. — jgill

Oh I love those symbols too, because they speak to and for me. I think in those symbols. I truly love epsilontics. My understanding is that Weierstrass gave us that gift.

And I never go that long without obsessing over the real numbers, and I mean the weird basics of the system. The constructions and whether or not they really satisfy. It's arguably better to just take the axioms as describing ideal entities indirectly. Or at least I find nested equivalence classes less than convincing. Though a single stream of rational numbers is reasonable. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismMy argument is that the idea of seeing beyond time to some sort of awareness or reality is incoherent. To be aware is to change. Pure anything , including pure timelessness, is not Being but the definition of death itself. — Joshs

I think the most charitable way to read it is as gazing on The Unchanging with adoration. Or feeling oneself in a sort of divine stasis, having temporarily become The Illuminated One. There's only One of 'em to, because it's the Central and Ideal State of Being. The capital letters aren't meant as a parody but only to capture the feeling I think is involved.

You know Sartre's talk about our desire to be like stones --to flee from our twisting and ragger nothingness and yet somehow keep our freedom in that stonelike plenitude. -

The Mind-Created World

How so ?You are appealing to a narrow concept of existence here. — Janus

To be sure, I'm using a fairly concrete analogy there (taken from L) , but I embrace the existence of all kinds of mental entities, mathematical entities, etc. Truly I think I have an especially inclusive sense of existence, limited only by possible experience -- hardly a stringent criterion for someone who tries to speak as a philosopher. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / Phenomenalism6.5 If a question can be put at all, then it can also be answered.

Incompleteness in mathematics puts a kink in this. Is "this and that" provable? Will "yes" or "no" always suffice? — jgill

You raise a good point. I can't endorse all of his claims, but some of them are great. I recommend checking out 5.6 and its leaves, which largely inspired this thread.

Here's a little comment he makes in passing in response to Kant's [ failed ] argument that space is not real.

A right-hand glove could be put on a left hand if it could be turned round in four-dimensional space. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismThe clock still ticks but what is truly and ultimately real is unchanging. — FrancisRay

A question that might be asked is whether this is true by definition --- whether we tend to understand 'Being' [the truly real ] precisely in terms of constant presence. If so, is this a bias ?

I'm of course not the first person to speculate in this way. I bring up a famous issue. Much of the radicality of Being and Time is perhaps in its claim or suggestion (according to some) that being is time. This is maybe like Heraclitus making the Flux itself most real.

My own view is that discursive philosophers really can't help looking for atemporal structure. That's the quasi-scientific conception of the enterprise at least. But perhaps we can articulate the perduring matrix or structure of the flow of otherwise continuous novelty. We can sketch the form or 'skeleton' of all possible experience. For instance, the rainbow shows us the palette with which reality must eternally be painted. The human ear experiences a certain range of tones. Wittgenstein tried to express the logical form of [the conceptual aspect of] the world. Mathematicians arguably disclose necessities in quantitative and spatial aspects of reality. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismI am not a fan of Nietzsche. He's brilliant but seems to be floundering around in the dark. — FrancisRay

I know that there are aspects of Nietzsche that hard to enjoy, but I definitely personally defend his overall philosophical greatness. To be clear, it's of course not a matter of endorsing all of his claims. It's more about the value of wrestling with an original and daring mind.

FWIW, I adore Emerson. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismAha. I can show you how to untangle it. It requires knowing only two or three vital facts. If you know that all metaphysical questions are undecidable then you're half way there. — FrancisRay

Not to be difficult, but claiming that all metaphysical questions are undecidable seems to decide an important metaphysical question. Though I can actually feel my way toward what you might mean. And I've maybe made similar claims, most recently in terms of an ineradicable ambiguity which I was calling semantic finitude.

To my ears, you are little too down on mainstream philosophy, forgetting maybe that it's not just the domain of respectable professors. And some of those professors are great anyway. Hegel was a professor, as was Heidegger and Husserl. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismCome on. Spit it out. :smile: — jgill

I'm glad someone caught my little joke.

The problem, as I see it, is that then a revolutionary idea is drowned in a sea of words. Being a math guy and not a philosopher, to be concise is paramount (though some in my former profession violate that principle). — jgill

I feel you. Did you ever look into the famous TLP ? It's got a tree structure, where you can open up any claim for more detail. But even with all the leaves out, it's still a brief, beautiful book. Definitely one of my favorites in the entire tradition, and a big influence on this thread.

Personally I'd like to squeeze the gist of anything I've learned into such a tight presentation, but I think it takes lots of experimentation (longwinded at times, and likely interactive ) to whittle it down. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismOne more quote that I think/hope you will relate to:

... if the only form of tradition, of handing down, consisted in following the ways of the immediate generation before us in a blind or timid adherence to its successes, “tradition” should positively be discouraged. ...Tradition is a matter of much wider significance. It cannot be inherited, and if you want it you must obtain it by great labour.

Some one said: “The dead writers are remote from us because we know so much more than they did.” Precisely, and they are that which we know.

Shakespeare acquired more essential history from Plutarch than most men could from the whole British Museum. What is to be insisted upon is that the poet must develop or procure the consciousness of the past and that he should continue to develop this consciousness throughout his career.

What happens is a continual surrender of himself as he is at the moment to something which is more valuable. The progress of an artist is a continual self-sacrifice, a continual extinction of personality.

There remains to define this process of depersonalization and its relation to the sense of tradition. It is in this depersonalization that art may be said to approach the condition of science.

That's T.S. Eliot

I think there's a 'good' discursive part of philosophy, some of it basically so creative as to be visionary. This or that person somehow cuts through the general confusion with just the right metaphor, just the right revelation of false necessity as mere contingency, opening up the space.

But we probably agree that philosophy can be a dreary excuse for conformity --a soporific even... -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismI also believe in the value of analysis, since although it cannot take us all the way to an understanding it clearly signposts what it is we need to understand and disposes of philosophical problems. For a sceptic analysis is the only way forward, since they will not be inclined to do the practice. — FrancisRay

I guess I find the discursive and 'the rest' to be pretty entangled. But I've been known to talk about the feeling of being 'behind language.' Or maybe 'over language. ' This is still a figure of speech, but it points at a 'feeling' or heightened state that triumphs over the useful neurotic discursivity, plays with it.

My own favored sense of mysticism is close to Nietzsche's interpretation of Jesus in The Antichrist.

...he regarded only subjective realities as realities, as “truths” ... he saw everything else, everything natural, temporal, spatial and historical, merely as signs, as materials for parables...

...

The “kingdom of heaven” is a state of the heart—not something to come “beyond the world” or “after death.” .. The “kingdom of God” is not something that men wait for: it had no yesterday and no day after tomorrow, it is not going to come at a “millennium”—it is an experience of the heart, it is everywhere and it is nowhere....

...

This faith does not formulate itself—it simply lives, and so guards itself against formulae. ...It is only on the theory that no word is to be taken literally that this anti-realist is able to speak at all. Set down among Hindus he would have made use of the concepts of Sankhya, and among Chinese he would have employed those of Lao-tse—and in neither case would it have made any difference to him.—With a little freedom in the use of words, one might actually call Jesus a “free spirit”—he cares nothing for what is established: the word killeth, whatever is established killeth. The idea of “life” as an experience, as he alone conceives it, stands opposed to his mind to every sort of word, formula, law, belief and dogma... -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / Phenomenalism“Dost thou reckon thyself only a puny form

When within thee the universe is folded?”

Baha’u’llah quoting Imam Ali,

the first Shia Imam — FrancisRay

:up:

Beautiful. Yeah I think we are on the same page in the most important way. The feeling tone, the sense of philosophy's radical potential, the sense of the 'illusory' nature of the ego. I'll even give you the 'illusory' nature of time in a certain sense. Though I think the form of flow itself is static. The river runs on smoothly forever. The reels of the projector turn. Hebel. Breath. Vapor. All procession is. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismWaves on the ocean or sparks of the divine are common metaphors for our situation as individuals. — FrancisRay

:up:

I suspect that this :

Indra's net (also called Indra's jewels or Indra's pearls, Sanskrit Indrajāla, Chinese: 因陀羅網) is a metaphor used to illustrate the concepts of Śūnyatā (emptiness),[1] pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination),[2] and interpenetration[3] in Buddhist philosophy.

is another way to say the same thing that I mean by ontological cubism.

Note that interpenetration is stressed. I 'am' my world in some sense, but of course I am our world, and you are in our world with me. But the world is arranged around sentient bodies, so that each of us is at the center of our own coordinate system. Our feet don't move. The street rolls beneath them. Einstein and Mach come to mind here, and not just Husserl. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismI'm going to add a supplement to the OP here. I think (?) the 'transcendence' of the object in phenomenology is little known and yet important. The relevance is the alternative to indirect realism and basically the idea that appearence hides [ or substitute for ] the 'true' nature of the object.

Husserl

Experience is flowing and 'horizonal.' I see the front of a house and have a sense of the unseen back of the house. I read the first few pages and have a vague sense of the many that follow. I 'get to know' someone, who I find interesting. Of course the 'now' itself is 'stretched' with anticatipation and memory, allowing me to appreciate music and understand a long sentence. Note that I constant expect expect expect, and that attention is drawn to violations of expectoration.The thing is given in experiences, and yet, it is not given; that is to say, the experience of it is givenness through presentations, through “appearings.” Each particular experience and similarly each connected, eventually closed sequence of experiences gives the experienced object in an essentially incomplete appearing, which is one-sided, many-sided, yet not all-sided, in accordance with everything that the thing “is.” Complete experience is something infinite. To require a complete experience of an object through an eventually closed act or, what amounts to the same thing, an eventually closed sequence of perceptions, which would intend the thing in a complete, definitive, and conclusive way is an absurdity; it is to require something which the essence of experience excludes.

Sartre

The thing is not behind its appearances but something like their ideal unity, which is 'infinite' in that the object can continue to be examined by me or others who might arrive. The worldly object is experienced as experienceable-by-others-too. It's a relatively permanent possibility of perception, projected into the future and into considerations of alternate versions of the past.MODERN thought has realized considerable progress by reducing the existent to the series of appearances which manifest it. Its aim was to overcome a certain number of dualisms which have embarrassed philosophy and to replace them by the monism of the phenomenon. Has the attempt been successful? In the first place we certainly thus get rid of that dualism which in the existent opposes interior to exterior. There is no longer an exterior for the existent if one means by that a superficial covering which hides from sight the true nature of the object. And this true nature in turn, if it is to be the secret reality of the thing, which one can have a presentiment of or which one can suppose but can never reach because it is the "interior" of the object under consideration-this nature no longer exists. The appearances which manifest the existent are neither interior nor exterior; they are all equal, they all refer to other appearances, and none of them is privileged. Force, for example, is not a metaphysical conatus of an unknown kind which hides behind its effects (accelerations, deviations, etc.); it is the totality of these effects. Similarly an electric current does not have a secret reverse side; it is nothing but the totality of the physical-chemical actions which manifest it (electrolysis, the incandescence of a carbon filament, the displacement of the needle of a galvanometer, etc.). No one of these actions alone is sufficient to reveal it. But no action indicates anything which is behind itself; it indicates only itself and the total series. The obvious conclusion is that the dualism of being and appearance IS no longer entitled to any legal status within philosophy. The appearance refers to the total series of appearances and not to a hidden reality which could drain to itself all the being of the existent. And the appearance for its part is not an inconsistent manifestation of this being. To the extent that men had believed in noumenal realities, they have presented appearance as a pure negative. It was "that which is not being"; it had no other being than that of illusion and error. But even this being was borrowed, it was itself a pretense, and philosophers met with the greatest difficulty in maintaining cohesion and existence in the appearance so that it should not itself be reabsorbed in the depth of nonphenomenal being. But if we once get away from what Nietzsche called "the illusion of worlds-behind-the-scene," and if we no longer believe in the being-behind-the-appearance, then the appearance becomes full positivity; its essence is an "appearing" which is no longer opposed to being but on the contrary is the measure of it. For the being of an existent is exactly what it appears.

...

Thus we arrive at the idea of the phenomenon such as we can find, for example in the "phenomenology" of Husserl or of Heidegger-the phenomenon or the relative-absolute. Relative the phenomenon remains, for "to appear" supposes in essence somebody to whom to appear. But it does not have the double relativity of Kant's Erscheinung. It does not point over its shoulder to a true being which would be, for it, absolute. What it is, it is absolutely, for it reveals itself as it is. The phenomenon can be studied and described as such, for it is absolutely indicative of itself. The appearance does not hide the essence, it reveals it; it is the essence. The essence of an existent is no longer a property sunk in the cavity of this existent; it is the manifest law which presides over the succession of its appearances, it is the principle of the series.

plaque flag

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum