-

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismThe painter, when he has to draw a round cup, knows very well that the opening of the cup is a circle. When he draws an ellipse, therefore, he is not sincere, he is making a concession to the lies of optics and perspective, he is telling a deliberate lie.

https://smarthistory.org/cubism-and-multiple-perspectives/

Is the opening really a circle ? This really-a-circle is a bit like the thing-in-itself, but note that it still relies on an idea viewing angle (straight on). It's still for and through the eyes that the circle is given. -

What is truth?I don't think so. You just hid truth in "better and better". You are just paraphrasing "A statement is better if it more closely approximates the truth". — Banno

That's just you reading in your own biases, as far as I can tell.

Some philosophers have imagined that to start an inquiry it was only necessary to utter a question or set in down upon paper, and have even recommended us to begin our studies with questioning everything. But the mere putting of a proposition into the interrogative form does not stimulate the mind to any struggle after belief. There must be a real and living doubt, and without this all discussion is idle.

https://www.bocc.ubi.pt/pag/peirce-charles-fixation-belief.pdf

Sometimes we aren't at ease with our beliefs. We don't know, ultimately, how we should behave (and this includes what we should call 'true,' but even more so whether we should ACT this or that way in the world.)

It is a very common idea that a demonstration must rest on some ultimate and absolutely indubitable propositions. These, according to one school, are first principles of a general nature; according to another, are first sensations. But, in point of fact, an inquiry, to have that completely satisfactory result called demonstration, has only to start with propositions perfectly free from all actual doubt. If the premisses are not in fact doubted at all, they cannot be more

satisfactory than they are.

Strong beliefs are enough. Calling our strong beliefs 'true' sprinkles no magic dust upon them. Get a gang of verbal primates together, and you'll have all the 'truth' you can stand.

Calling beliefs 'better' is, I admit, similar to calling them 'true.' But that doesn't defeat the perspectivist point here. Of course (usually!) my beliefs are true and better. We tend to write Whiggish histories of our sets of beliefs. 'I know better now.' Moving from an anguished state of doubt to the resolution of a fixed-for-now-belief is sweet relief.

In short, you haven't shown any role for 'true' after all, beyond mere endorsement (the prosentential (pronounish) use I don't deny, but it's not that exciting here.)

[ Note that I don't follow Peirce all the way, but I endorse what's quoted here.] -

The Mind-Created WorldI think we can 'fix' and update Berkeley. Or that it's already been done, but it's helpful to retrace the steps.

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4723/pg4723-images.htmlIt is indeed an opinion STRANGELY prevailing amongst men, that houses, mountains, rivers, and in a word all sensible objects, have an existence, natural or real, distinct from their being perceived by the understanding. But...what are the fore-mentioned objects but the things we perceive by sense? and what do we PERCEIVE BESIDES OUR OWN IDEAS OR SENSATIONS? and is it not plainly repugnant that any one of these, or any combination of them, should exist unperceived? — B

Berkeley should not, in my view, have said that we perceive our own own ideas and sensations. What he [ should have ] meant is that we understand such things as they tend to be perceived. And any 'idealist' must address the permanence of mountains, for instance, which outlast generations.

He goes on to drag in God, and he problematically takes spirits in the same naive way his opponents take independent objects. @Leontiskos mentions overcorrection. I think Berkeley overcorrects. The 'pure' subjectivity of the spirit is the 'same' error as the 'pure' aperspectival object on the other side.Some truths there are so near and obvious to the mind that a man need only open his eyes to see them. Such I take this important one to be, viz., that all the choir of heaven and furniture of the earth, in a word all those bodies which compose the mighty frame of the world, have not any subsistence without a mind, that their BEING (ESSE) is to be perceived or known... — B

[/quote]

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4723/pg4723-images.html

What is given is a daily embodied experience of the usual objects in the familiar lifeworld. Someone like Berkeley could have merely challenged the semantic emptiness of talk of the pure object.

https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100322668The philosophy of perception that elaborates the idea that, in the words of J. S. Mill, ‘objects are the permanent possibilities of sensation’. To inhabit a world of independent, external objects is, on this view, to be the subject of actual and possible orderly experiences. Espoused by Russell, the view issued in a programme of translating talk about physical objects and their locations into talk about possible experiences (see logical construction). The attempt is widely supposed to have failed, and the priority the approach gives to experience has been much criticized. — link

As William James and Ernst Mach saw, such pure 'experience' is no longer experience consciousness or awareness at all but just the neutral being of a world given perspectively. This neutral stuff is of course organized into 'appearance' and 'reality' with respect to practical goals.

We find a version of this in Kant.

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4280/pg4280-images.html#chap77That there may be inhabitants in the moon, although no one has ever observed them, must certainly be admitted; but this assertion means only, that we may in the possible progress of experience discover them at some future time. For that which stands in connection with a perception according to the laws of the progress of experience is real. They are therefore really existent, if they stand in empirical connection with my actual or real consciousness, although they are not in themselves real, that is, apart from the progress of experience. — Kant -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismFor example, if I was hooked up to a machine and someone said "I'm going to press a button and you're going to experience enacting x exact internal monologue, feel happy, see a green pony walk into the room, then lift your arms up and yell "I love Newt Gingrich," and mean it," and the person pressed the button and all that actually happened, I'd assume that whatever technology they were using implied enough mastery of the causes of sentience that they could tell me if a given AI experiences it or not. The reason P Zombies are a problem, IMO, is that we actually don't have a good idea what causes sentience, and so we don't know what to look for to determine what things have it. — Count Timothy von Icarus

You make a good point. But there's still maybe a gap here between steering sentience and creating or understanding it. I readily admit that technical power is even dangerously persuasive.

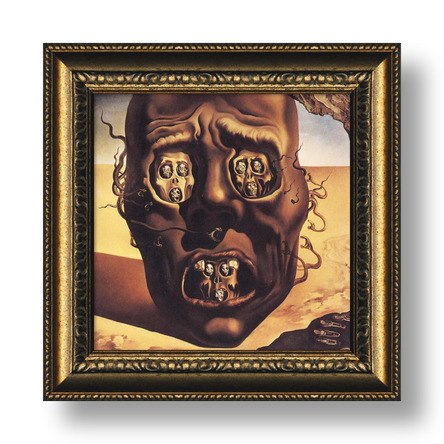

FWIW, I think we do take our fellow humans and sufficiently complex animals as sentient. So we 'do' already know what to look for in that sense. But in some sense 'my' pain (and so on) is mine. I see the object from one side, you from another. Everyone is seemingly forced to see the object only from this or that place at this or that moment. 'Ontological cubism.' The world is an 'infinite' or hypersaturated object which is only given in such slices or adumbrations. The shiny world that hovers in Euclidean space is a useful 'fiction,' an important piece of culture which perfects the transparency of the subject.

So for me the larger issue is not consciousness detection but consciousness as the very being of a world entangled in our cognition, as it is itself enclosed in the world (a Klein bottle, a Möbius strip.) -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismHusserl’s genetic method begins with an ego-intentionality which we imagine as preceding the constitution of any regularities in experience. At this point there isnt much to determine that there is something like ‘the’ world, if this is to indicate a realm of recognizable regularities, patterns and meaning. So what sort of process is required to turn a chaos of meaningless flux into the meaningful, stable patterns that would justify calling what we experience ‘the’ world? — Joshs

It seems to me that self and world would have to be elaborated at the same time. The body is especially entangled and undecidable, for it is revealed and revealing. The (psychological) self too is made of patterns and boundaries, right ? The 'pure witness' is, in my view, anonymous being, more like a clearing or the light that shines on the scene of development. Or really just its being there. Just its happening.

FWIW, I don't think babies are able to think of being in this world, but I think we practiced concept-mongers understand their awareness to be awareness of the world. -

The Mind-Created WorldAnd this sort of thinking seems to make it easy to fall into circles asking about what things are maps and what things are territories. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I like to think of maps as little pieces of reality that have some of the same structure as bigger pieces of reality.

I think we can (and do, without always noticing it) put all entities in the same inferential nexus. So it's all real, but various things exist differently (prime numbers don't exist like petunias.) -

The Mind-Created WorldYet your 'perspectivalism' seems to be a quasi-rejection of mind-independent objects, and that strikes me as an overcorrection, like falling off the other side of the horse instead of regaining balance. — Leontiskos

I think J. S. Mill has a nice take. Objects are only independent in the sense that they are 'permanent possibilities of sensation.' So the world is not a video game where the couch disappears when we leave the room. Instead we understand couches in the first place in terms of how humans tend to experience them. I can wander into the living room and plop down with a book. And the couch doesn't vanish when I die (I inherited it, after all.)

Speaking as someone who embraces perspectivism and correlationism, I'd would not call the world 'mind-created' or basically mental. But I would insist that the lifeworld is a kind of unbreakable unity, and that embodied perspectival creatures like us don't have a strong grip on the idea of independent objects -- except for one that boils down to 'permanent possibilities of sensation.'

'To be is to be < potentially > perceivable. ' And this, in my view, is more of a semantic claim. -

The Mind-Created WorldBut is my claim about the boulder meaningless and unintelligible outside of any perspective? Does not the idea that a boulder has a shape transcend perspective? — Leontiskos

Hi, Leontiskos ! Though I'd jump in here.

The boulder's shape is independent, in some sense, from this or that individual human perspective. So it transcends the limitations of my eyesight or yours. But it seems to me that what we could even mean by 'shape' depends on an experience that has always been embodied and perspectival.

Has anyone ever experienced a spatial object a-perspectively ? -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismI think if we had something like the technology mentioned above, something such that someone could control what you see, the emotions you feel, and even the words of your internal monologue by "playing" your nervous system like a piano, then most people would say we've sufficiently grounded the causal underpinnings of experience to be able to tell when something is conscious at a human level versus just appearing so, even if we can't fully explain exactly where that consciousness emerges on the level from zygote to new born. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I still think you maybe aren't addressing the being issue ? Or, more likely, I'm being muddy in making my point.

First, there's the relatively boring consciousness, which is 'just' sufficiently sophisticated interactive behavior. It wouldn't actually be boring (we might fall in love), but it's a definite mundanization of the concept consciousness. It's more like intelligence or self-modelling. Turing test stuff, really. Can we imagine sapience without sentience ? I found a baby turtle in the woods today. Perhaps the best AI tech of 2085, which we'll call Charlie, will be much more sapient but not sentient at all. I may be able to learn from Charlie, but does Charlie 'have' the world ?

So the'exciting' kind of consciousness is of course the 'thereness' of the world 'for' sentience (a condition for the possibility of actually rather than merely seeming to give a damn). I think the world only exists perspectively. But I also can't make sense of sentience outside of a world. I'm a correlationist, I guess. But not an idealist, as if subjectivity could make sense except as the-world-for. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / Phenomenalism“…only idealism, in all its forms, attempts to lay hold of subjectivity as subjectivity and to do justice to the fact that the world is never given to the subject and the communities of subjects in any other way than as the subjectively relative valid world with particular experiential content and as a world which, in and through subjectivity, takes on ever new transformations of meaning; and that even the apodictically persisting conviction of one and the same world, exhibiting itself subjectively in changing ways, is a conviction motivated purely within subjectivity, a conviction whose sense—the world itself, the actually existing world—never surpasses the subjectivity that brings it about.

There's much to like about this quote, but the world and the subject are interdependent. The subject 'is' the care-structured streaming of the world. Entangled, correlated.

The world is never the same 'twice,' and yet I am describing the world, as predictably infinitely novel. Concepts have a relative stability that makes our conversation possible. I 'know' that people never perfectly understand one another. It's fog and blur forever. But we try to find the least worst words for it all. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismThe trouble with phenomenology is that it is effectively naive realism and can never produce a fundamental theory. . . . — FrancisRay

We must have radically different conceptions of phenomenology. I'd say it's largely the opposite of naive realism. Though I will grant that it sometimes comes back around to a highly sophisticated direct realism. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / Phenomenalism

:up:Nothing in our experience of the world ever gives us the justification to claim that what we see is the ‘same’ object, except in a relative way. — Joshs

Perhaps you don't see that I see that part very well. The object-for-me is not, in an important sense, the object-for-you. But it's the essence of conceptuality to make the unequal equal. We must tame the chaos, lump things together. I think Lakoff and Hofstadter and right that we are deeply metaphorical, analogical beings, reusing a pattern grasped here also over there. Philosophy is nonfiction poetry. We speak of the stream of consciousness or the streaming of time. We float an anemic mythology. We speak of radicality and basis, still dirtworshipppers pointing at roots and soil.

To me phenomenology is largely about making the transparent opaque. We look right through the glass of our subjectivity. If I turn my head, I 'know' its not the whole world twisting. If I close my eyes, I know the lights didn't just go off.

When a crowd of people all observe a rocket bursting, they will ignore whatever there is reason to think peculiar and personal in their experience, and will not realize without an effort that there is any private element in what they see. But they can, if necessary, become aware of these elements. One part of the crowd sees the rocket on the right, one on the left, and so on. Thus when each person's perception is studied in its fullness, and not in the abstract form which is most convenient for conveying information about the outside world, the perception becomes a datum forpsychologyphenomenology. — Russell. --- I changed the last word

You might not find this fancy or difficult enough (I'm joking with you), but I think Russell is doing a pretty good job of pointing out the natural attitude, for which subjectivity is conveniently transparent. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismI don't think so. The "hard problem," is the problem of explaining how consciousness arises and how it produces its subjective qualities through a scientific theory that has the same rigor, comprehensiveness, and depth as any other of the major scientific theories we are familiar with (e.g., explanations of cellular reproduction.) If that's sort of answer you're looking for, this sort of framing isn't going to help you. — Count Timothy von Icarus

But if consciousness is the being of the world, we have what's maybe even a deeper problem.

Just to be clear, I'm not in the 'nothing to see here' camp. Basically Madonna was right that life is a mystery. You give some good examples of us always being able to ask why. As far as I can tell, there 'must' be brute fact, just given the structure of our cognition.

I've gone back and forth on the p-zombie issue. But at the moment I think Husserl is right. It's something like empathy that convinces us of the reality of others. It's automatic. A sufficiently sophisticated android could make us fall in love with it, give our lives to save it from danger. I don't know if/when we'll get there technologically. But there is a kind of privacy to pain and pleasure, despite their undeniable social aspect, which (as Wittgenstein and others point out) makes talking about them possible. Nevertheless, I 'am' a perspective on the world. And I trust that so are you.

Can scientific methods tell an ideal p-zombie from the real thing ? What does this mean exactly ? If consciousness is the being of the world from a strangely private perspective,...?

All I can imagine is finding causal relationships and so on between thinks that get taken as conscious. But a public criterion for consciousness 'has' to include androids of a certain quality. The hard problem either looks so hard that 'problem' feels like the wrong word or it melts into something tractable but no longer so exciting ---a mere branch of AI perhaps, at least implicitly. -

The Mind-Created WorldAre the contents of experience just what we experience? — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think so lately, and for me it feels like a great clarification. Lots of ways to say it, but one way is : consciousness is precisely the being of the world from or for a perspective. This chucks indirect realism out the window. My toothaches and daydreams are in your world, but language always intends our world. My 'private' thoughts are just locked away in a dark closet which is nevertheless very much within the inferential space of the community. -

The Mind-Created WorldI take consciousness to be the awareness of awareness, and perhaps awareness is the judgement of judgement, and judgement is the first responsive action, and the first judgement is the distinguishing of the organism from the environment by the organism itself. — unenlightened

:up:

I like the concepts of sapience and sentience. I'd say there's a un-self-thematizing consciousness in sentience, and that something fancier appears with sapience. Judgement is linguistic, and, within a community, one is held accountable for one's judgements. Definitely getting into Brandom / Sellars territory here. -

The Mind-Created Worldn object outside the seer can be beheld by the seer. How can the seer see himself? How is it possible? You cannot see the seer of seeing. You cannot hear the hearer of hearing. You cannot think the Thinker of thinking. You cannot understand the Understander of understanding. That is the ātman. — Brihadaranyaka Upaniṣad

A shallow objection to this involves handing the seer a mirror, but I think that something like being is intended, and that seeing is a metaphor for being. Presumably the dead don't see (have no world), so it's not absurd to reach for eyes and ears as a metaphor. Yet we obviously we see the eyes of others seeing, and our own in the mirror, so the intention must be metaphorical.

It is not how things are in the world that is mystical, but that it exists.

...

The experience that we need in order to understand logic is not that something or other is the state of things, but that something is: that, however, is not experience.

To say 'I wonder at such and such being the case' has only sense if I can imagine it not to be the case. In this sense one can wonder at the existence of, say, a house when one sees it and has not visited it for a long time and has imagined that it had been pulled down in the meantime. But it is nonsense to say that I wonder at the existence of the world, because I cannot imagine it not existing. I could of course wonder at the world round me being as it is. If for instance I had this experience while looking into the blue sky, I could wonder at the sky being blue as opposed to the case when it's clouded. But that's not what I mean. I am wondering at the sky being whatever it is. One might be tempted to say that what I am wondering at is a tautology, namely at the sky being blue or not blue. But then it's just nonsense to say that one is wondering at a tautology. — Wittgenstein -

The Mind-Created WorldI'm inclined to say that the mind is never an object, although that usually provokes a lot of criticism. I've long been persuaded by a specific idea from Indian philosophy, namely, that the 'eye cannot see itself, the hand cannot grasp itself. The 'inextricably mental' aspect is simply 'the act of seeing'. — Wayfarer

I like to read this in terms of the famous ontological difference, in terms of being itself not being an entity ---though of course the concept of being itself is indeed an entity.

Central to Heidegger's philosophy is the difference between being as such and specific entities.[48][49] He calls this the "ontological difference", and accuses the Western tradition in philosophy of being forgetful of this distinction, which has led to misunderstanding "being as such" as a distinct entity.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heideggerian_terminology

I mention & quote Wittgenstein again (emphasis mine), because his presentation is so concentrated.

https://www.wittgensteinproject.org/w/index.php?title=Tractatus_Logico-Philosophicus_(tree-like_view)In fact what solipsism means, is quite correct, only it cannot be said, but it shows itself.

That the world is my world, shows itself in the fact that the limits of the language (the language which I understand) mean the limits of my world. The world and life are one.

I am my world. (The microcosm.)

Where in the world is a metaphysical subject to be noted? You say that this case is altogether like that of the eye and the field of sight. But you do not really see the eye. And from nothing in the field of sight can it be concluded that it is seen from an eye.

That the world is my world, shows itself in the fact that the limits of the language (the language which I understand) mean the limits of my world.

Here we see that solipsism strictly carried out coincides with pure realism. The I in solipsism shrinks to an extensionless point and there remains the reality co-ordinated with it.

There is therefore really a sense in which in philosophy we can talk of a non-psychological I.

The I occurs in philosophy through the fact that the "world is my world".

The philosophical I is not the man, not the human body or the human soul of which psychology treats, but the metaphysical subject, the limit—not a part of the world.

Note the connection of language and solipsism. My belief is the structure of the world itself, but from my perspective. I am this world-from-a-perspective. My beliefs about the world are not 'inside' me. They are simply [ the 'conceptual aspect' of] the world itself --- as it is given to a 'me' that vanishes or melts into this perspectively given world, as its form.

I understand that the lived body looks to be a sine qua non of experience of the world, so it's tempting to make mind fundamental, but I think 'being' is the deepest term, and that the deepest term ought to be radically 'empty' or 'neutral' and before all division. -

The Mind-Created World

I think this gels with what you are saying.

Different minds may set out with the most antagonistic views, but the progress of investigation carries them by a force outside of themselves to one and the same conclusion. This activity of thought by which we are carried, not where we wish, but to a fore-ordained goal, is like the operation of destiny. No modification of the point of view taken, no selection of other facts for study, no natural bent of mind even, can enable a man to escape the predestinate opinion. This great hope is embodied in the conception of truth and reality. The opinion which is fated to be ultimately agreed to by all who investigate, is what we mean by the truth, and the object represented in this opinion is the real. That is the way I would explain reality.

But it may be said that this view is directly opposed to the abstract definition which we have given of reality, inasmuch as it makes the characters of the real depend on what is ultimately thought about them. But the answer to this is that, on the one hand, reality is independent, not necessarily of thought in general, but only of what you or I or any finite number of men may think about it; and that, on the other hand, though the object of the final opinion depends on what that opinion is, yet what that opinion is does not depend on what you or I or any man thinks. Our perversity and that of others may indefinitely postpone the settlement of opinion; it might even conceivably cause an arbitrary proposition to be universally accepted as long as the human race should last. Yet even that would not change the nature of the belief, which alone could be the result of investigation carried sufficiently far; and if, after the extinction of our race, another should arise with faculties and disposition for investigation, that true opinion must be the one which they would ultimately come to. — Peirce

The truth (or rather its best surrogate) is belief which is objective and bias-transcending as possible. The world exists meaningly [only ] 'for' an articulate (and therefore social) creature. C. S. Peirce calls it the 'settlement of opinion,' which I think of in terms of the evolution of perspective. Wittgenstein wants to [help us] 'see the world aright' (properly, correctly.)

The opinion which is fated to be ultimately agreed to by all who investigate, is what we mean by the truth, and the object represented in this opinion is the real. That is the way I would explain reality.

The real is the world as [linguistically] grasped by the ideal point-of-view, which is also a point-at-infinity, a goal on the horizon. So the 'mental' (meaning, culture, science, rationality, normativity, spirit) is indeed fundamental and irreducible here. -

The Mind-Created WorldI also don't know if I would agree with the "idealism" route though. Lately, I've been trying to figure out if there is even a distinction between "physicalism" and "idealism" once one steps outside of the box of substance metaphysics. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Have you ever looked into Mach's The Analysis of Sensations ?

A common and popular way of thinking and speaking is to contrast " appearance " with " reality." A pencil held in front of us in the air is seen by us as straight; dip it into the water, and we see it crooked. In the latter case we say that the pencil appears crooked, but is in reality straight. But what justifies us in declaring one fact rather than another to be the reality, and degrading the other to the level of appearance ? In both cases we have to do with facts which present us with different combinations of the elements, combinations which in the two cases are differently conditioned. Precisely because of its environment the pencil dipped in water is optically crooked; but it is tactually and metrically straight. An image in a concave or flat mirror is only visible, whereas under other and ordinary circumstances a tangible body as well corresponds to the visible image. A bright surface is brighter beside a dark surface than beside one brighter than itself. To be sure, our expectation is deceived when, not paying sufficient attention to the conditions, and substituting for one another different cases of the combination, we fall into the natural error of expecting what we are accustomed to, although the case may be an unusual one. The facts are not to blame for that. In these cases, to speak of " appearance " may have a practical meaning, but cannot have a scientific meaning. Similarly, the question which is often asked, whether the world is real or whether we merely dream it, is devoid of all scientific meaning. Even the wildest dream is a fact as much as any other. If our dreams were more regular, more connected, more stable, they would also have more practical importance for us. In our waking hours the relations of the elements to one another are immensely amplified in comparison with what they were in our dreams. We recognise the dream for what it is. When the process is reversed, the field of psychic vision is narrowed; the contrast is almost entirely lacking. Where there is no contrast, the distinction between dream and waking, between appearance and reality, is quite otiose and worthless.

The popular notion of an antithesis between appearance and reality has exercised a very powerful influence on scientific and philosophical thought. We see this, for example, in Plato's pregnant and poetical fiction of the Cave, in which, with our backs turned towards the fire, we observe merely the shadows of what passes (Republic, vii. 1). But this conception was not thought out to its final consequences, with the result that it has had an unfortunate influence on our ideas about the universe. The universe, of which nevertheless we are a part, became completely separated from us, and was removed an infinite distance away.

...

As soon as we have perceived that the supposed unities " body " and " ego " are only makeshifts, designed for provisional orientation and for definite practical ends (so that we may take hold of bodies, protect ourselves against pain, and so forth), we find ourselves obliged, in many more advanced scientific investigations, to abandon them as insufficient and inappropriate. The antithesis between ego and world, between sensation (appearance) and thing, then vanishes, and we have simply to deal with the connexion of the elements a b c . . . A B C . . . K L M . . ., of which this antithesis was only a partially appropriate and imperfect expression. This connexion is nothing more or less than the combination of the above-mentioned elements with other similar elements (time and space). Science has simply to accept this connexion, and to get its bearings in it, without at once wanting to explain its existence.

https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/mach.htm -

What is truth?Here are some of my beliefs on this matter :

1. All we ever have is beliefs.

2. We [ mostly ] use 'true' to say that we have or share a belief.

3. My belief is how the world is given to me ---reduced to its conceptual aspect, because I can't put the world in its sensual fullness in my talk.

4. The world is only given to individuals who experience it as meaningfully structured (who 'live' in those beliefs as simply the concept-aspect of world for them.)

5. All we can do is try to get better and better beliefs --- get a better 'view' on the one world we share -- often by discussing our beliefs with others to discover biases and inadequacy in those we currently have.

Note that truth doesn't matter. No one sees around their own perspective to some naked reality, because that reality would not be meaningfully/linguistically structured.

Belief is the intelligible structure [conceptual skeleton ] of the world as given to or grasped by a person. — plaque flag

I shared some beliefs about belief. how I understand belief. I of course call them 'true,' for this (as I make explicit) is simply to trivially agree with myself. My beliefs are roughly the articulation of my perspective on the world, the way I see things which I understand to transcend me, to be things in our one shared world.Ha, is that so? Is it true? Or is it just your belief? — Banno

I've already answered that question: All we can do is try to get better and better beliefs --- get a better 'view' on the one world we share -- often by discussing our beliefs with others to discover biases and inadequacy in those we currently have. I expect that you read newspapers or their modern equivalent, the 'mere beliefs' of various philosophers.And if it is just a belief of yours, why should we pay it any attention? And if you believe it, don't you by that very fact believe that it is true? — Banno

We do differentiate between what folk believe and what is true. A pragmatic account such as you present loses this distinction. — Banno

We differentiate between what we do and do not believe. My account does not lose this distinction. It seeks to clarify what 'true' means. To take 'P' for true is to 'have' the world in a certain way.

You may believe in something like a world from no perspective that makes statements true, a world of things in themselves, apart from human cognition and language. But such a view seems paradoxical and confused to me. As Peirce saw, the game is settling beliefs.

What is familiar to us is the modification of our beliefs. Entire communities (we rational, scientific ones) end up 'knowing' this or that, accepting various statements as premises in arguments. Certain interpretations become obvious and dominant, pretty much unquestionable. We probably agree here about the massive background of shared beliefs that make ordinary life and conversation possible. -

The Mind-Created WorldObjectivity is what we hope to arrive at when we try to eliminate the (relevant) biases of any particular point of view. But the "objective view," is still a view; it is not what we arrive at when we have no point of view (as you point out, this makes no sense). When we want an objective view of a phenomena we try to observe it in many different ways, using instruments, creating clever experiments, trying to overcome biases. If the objective view we were after was "what phenomena are like without a mind," scientists could just shoot up anesthesia and achieve something to that effect. — Count Timothy von Icarus

:up: -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismSpeaking quite universally, the surrounding world is not a world "in itself" but is rather a world "for me," precisely the surrounding world of its Ego-subject, a world experienced by the subject or grasped consciously in some other way and posited by the subject in his intentional lived experiences with the sense-content of the moment. As such, the surrounding world is in a certain way always in the process of becoming, constantly producing itself by means of transformations of sense and ever new formations of sense along with the concomitant positings and annullings.

...

To begin with, the world is, in its core, a world appearing to the senses and characterized as "on hand," a world given in straightforward empirical intuitions and perhaps grasped actively. The Ego then finds itself related to this empirical world in new acts, e.g., in acts of valuing or in acts of pleasure and displeasure. In these acts, the object is brought to consciousness as valuable, pleasant, beautiful, etc., and indeed this happens in various ways, e.g., in original givenness. In that case, there is

built, upon the substratum of mere intuitive representing, an evaluating which, if we presuppose it, plays, in the immediacy of its lively motivation, the role of a value-"perception" (in our terms, a value-reception) in which the value character itself is given in original intuition. — Husserl

Note this part: the value character itself is given in original intuition. This is the stream before it's been analyzed or divided into its subjective and objective components. This value dimension in the worldstream is probably, more than anything, what gives it an teleologically egoic structure. I am the there itself, and yet the there tends to flow so that my belly stays full. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismWhen Husserl says that through empirical knowledge we come to see our perception of a thing as only our subjective perspective on the ‘same’ thing that others see, he means that it is the peculiar function of empirical objectivity to give the impression , through apperceptive idealization, of a unity where there is only similarity. Through the reduction we can come to see that it is not the same empirical thing we all see from our own vantage, any more than the aspectual features unfolding in our apprehension of a spatial object belong to the ‘same’ object. — Joshs

I claim that we see the same object differently. Even I, by myself, see the same object differently as I walk around it or shine my flashlight on it. The object transcends and unifies its adumbrations.

Our perspectively given 'worlds' are glued together with our language and our profoundly empathetic/social intentions. I (usually) intend precisely the practical-shared-worldly object. I can't even begin to do philosophy without talking about, intending, our world. So we don't have a plurality of worlds but a plurality of perspectives on the same world. Different people can step in the same river, though it's never given (experienced) in the same way twice. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / Phenomenalism“The fundamental form of this universal synthesis, the form that makes all other syntheses of consciousness possible, is the all embracing consciousness of internal time.” — Joshs

The issue is whether it should still be called 'consciousness.' There's an original eruption of flowing presence, the 'stream' of consciousness or experience or sentience. But what is this experience made of ? If not the world ? So the world is 'given' (is there) so that (for instance) its visual aspect largely determined by the turning of a creatures neck. The lived body's centrality suggests calling it consciousness, but this lived body is itself in the world. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismThe transcendent ego is not a subject as opposed to an object. It is a synthetic structure composed of a subjective (noetic) and objective (noematic) pole. It is only abstractively that we can think of these poles separately from each other. — Joshs

It seems we basically agree on this issue. The more radically we take subjectivity, the less it remains subject as opposed to object. We move to the undifferentiated unity of both, toward a streaming flux of becoming. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismFor the world of time and space this is the case. — FrancisRay

:up:

In what sense do you call it neutral? — FrancisRay

It is neutral as being neither mind or nor matter, prior to both.

https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/us/james1.htmI believe that ‘consciousness,’ when once it has evaporated to this estate of pure diaphaneity, is on the point of disappearing altogether. It is the name of a nonentity, and has no right to a place among first principles. Those who still cling to it are clinging to a mere echo, the faint rumor left behind by the disappearing ‘soul’ upon the air of philosophy. During the past year, I have read a number of articles whose authors seemed just on the point of abandoning the notion of consciousness,[1] and substituting for it that of an absolute experience not due to two factors. But they were not quite radical enough, not quite daring enough in their negations. For twenty years past I have mistrusted ‘consciousness’ as an entity; for seven or eight years past I have suggested its non-existence to my students, and tried to give them its pragmatic equivalent in realities of experience. It seems to me that the hour is ripe for it to be openly and universally discarded.

To deny plumply that ‘consciousness’ exists seems so absurd on the face of it – for undeniably ‘thoughts’ do exist – that I fear some readers will follow me no farther. Let me then immediately explain that I mean only to deny that the word stands for an entity, but to insist most emphatically that it does stand for a function.

I'd say that people are conscious of (aware of) the world. The world only exists in this way, or so I suggest, but we have to include the whole horizonal lifeworld and J . S . Mill's permanent possibilities of perception. We have to accept that daydreams and prime numbers exist just like lobsters and contracts, differently yes but in the same logical-inferential nexus.

I speculate that the problem has been so difficult for philosophy because methodological solipsism gets the perspectival form of the world right but typically fails to integrate the equally important insight into the profound and even foundational sociality of reason. I credit Feuerbach for his clarity on their relationship.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ludwig-feuerbach/Unlike sense experience, thought is essentially communicable. Thinking is not an activity performed by the individual person qua individual. It is the activity of spirit, to which Hegel famously referred in the Phenomenology as “‘I’ that is ‘We’ and ‘We’ that is ‘I’” (Hegel [1807] 1977: 110).

Culture is softwhere running on the crowd. No particular individual is needed, but the absense of all flesh (all hardware) would be the end of the game. We might also think of a flame jumping from melting candle to melting candle, or of data moving from storage device to storage device. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismHere's a description of the obvious that is nevertheless ontologically significant.

Each I finds itself as a middle point, so to speak a zero-point of a system of coordinates, in reference to which the I considers, arranges, and cognizes all things of the world, the already known or the unknown. But each I apprehends this middle point as something relative. For example, the I changes bodily its place in space, and while it continues to say “here” it knows that “here” in each case is spatially different....

The same holds for things. Each person has around himself the same world and perhaps several see the same thing, the same segment of the world. But each has his thing-appearance: The same thing appears for each in a different way in accordance with the different place in space. The thing has its front and back, above and below. And what is my front of the thing is for the other perhaps its back, and so on. But it is the same thing with the same properties. — Husserl : Basic Problems Lecture (available free online )

Who has ever experience the world differently ? And can I even make sense of one who claims to not see perspectively, not find themselves at the center of space ? This is the world as we know it, where to be is to be perceived or at least perceivable. That's the being we can make sense of. So the issue is largely semantic. We move on to the ego.

Each of us knows himself as an I. Now, being in that attitude where each of us finds himself present as an I, what does each of us find present in himself and in connection with himself ? We began thus with a description of the kind that everyone had to say “I,” and it was to this that everything else was tied. It is best to speak here in the singular first person and to continue thus: I posit myself as being and as being this here, as being with this and that determinate content. I posit me as experiencing this and that; I have such and such dispositions and acts. But I do not posit me as a disposition or an act; I do not come upon me as a disposition or an act.

Further, I posit me and find me not only present as an experiencing subject but also as a subject of personal properties, as a person with a certain character, as having certain intellectual and moral dispositions, etc. This I find to be present, of course, in a completely different way than I find my experiences to be present.

Further, I find me and what is mine as having duration in time, as changing or not changing during their duration, and I distinguish the flowing Now and the still given “just past” in retention. Further, in recollection I come upon myself as being the very same one who existed earlier, as still perduring now, s the one who perdured earlier on, who experienced such and such things in succession, etc.

Further, I have, as I find this, a lived body; and the lived body is a thing among other things that I likewise come upon. I also find this in time: In the Now, the existing lived body as my body; in the just past, the lived body which has just been; in recollection, the recollected body — the lived body belongs to me at all times.

This can be framed in terms of a worldstreaming centered on ('in') a 'lived body' which is embedded in a conceptual culture. But of course I manage my persona, my mask. I am caught up as an 'I' in something like Brandom's normative inferential semantics. My 'I' exists in various layers in the world. But (I claim) the deepest 'I' (Wittgenstein's, etc.) is no longer an 'I' except in the most minimal sense --as the being of a world which is given with a reliably perspectival form. Granted that the stream of experience changes, are their general structures which are relatively constant ? I think Husserl and Heidegger and others have tried to sketch that relatively constant structure. If being is a river, it has a shape. (?)

I'll end by referring back to GoldenEye (video games given only via first-person perspectives) and ontological cubism.The psychological I belongs to objective time, the same time to which the spatial world belongs, to the

time that is measured by clocks and other chronometers. And this I is connected to, in a spatial-temporal way, the lived body, upon whose functioning the psychical states and acts (which, once again, are ordered within objective time) are dependent, dependent in their objective, i.e., their spatial–temporal existence and condition. Everything psychical is spatial–temporal. Even if one holds it to be an absurdity, and perhaps justifiably so, that the psychical I itself (along with its experiences) has extension and place, it does have an existence in space, namely as the I of the respective lived body, which has its objective place in space. And therefore each person says naturally and rightly : I am now here and later there. — Husserl -

The Mind-Created WorldI offer this not as an appeal to authority but only as potentially useful.

Is phenomenological research solipsistic research? Does it restrict the research to the individual I and, more precisely, to the area of its individual psychic phenomena? It is anything but this. Solus ipse — that would mean I alone exist or I disengage everything remaining of the world, excepting only myself and my psychic states and acts.

On the contrary, as a phenomenologist, I disengage myself just as I disengage everyone else and the entire world, and no less my psychic states and acts, which, as my states and acts, are precisely nature. One may say that the nonsensical epistemology of solipsism emerges when, being ignorant of the radical principle of the phenomenological reduction, yet similarly intent on suspending all transcendence, one confuses the psychological and the psychologistic immanence with the genuine phenomenological immanence. — Husserl

I disengage myself just as I disengage everyone else and the entire world, and no less my psychic states and acts, which, as my states and acts, are precisely nature.

I read this as: the ego, which might be postulated as constituting, is at least also one more thing in the world, so that it would have to be self-constituting. It seems cleaner to me to indeed grant the lived body the status of a sine qua non...but to hesitate to speak of the priority of mentality. The lifeworld is 'given' as a rushing river, as a symphony. I can't see without a brain, but I also need eyes. But then I also need something in the world to see. And perception is conceptual (Sellars was mentioned above), so I need a linguistic conceptual community too. This without-which-nothing or condition-for-the-possibility approach memorably appears in The Fire Sermon.

The mind is burning, ideas are burning, mind-consciousness is burning, mind-contact is burning, also whatever is felt as pleasant or painful or neither-painful-nor-pleasant that arises with mind-contact for its indispensable condition, that too is burning. Burning with what? Burning with the fire of lust, with the fire of hate, with the fire of delusion. — Fire Sermon

I can sum up by suggesting that it's enough to challenge the intelligibility of the 'pure' object. We probably don't want to put ourselves in the vulnerable position of proposing a pure subject. -

The Mind-Created WorldReality has an inextricably mental aspect, which itself is never revealed in empirical analysis ¹. Whatever experience we have or knowledge we possess, it always occurs to a subject — a subject which only ever appears as us, as subject, not to us, as object.' — Wayfarer

I tend to agree with the spirit of what you are saying in this thread, but I think this metaphysical subject must be dissolved,

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/sartre/#TranEgoDiscInteInstead of a transcendental subject, the Ego must consequently be understood as a transcendent object similar to any other object, with the only difference that it is given to us through a particular kind of experience, i.e., reflection. The Ego, Sartre argues, “is outside, in the world. It is a being of the world, like the Ego of another” (Sartre 1936a [1957: 31; 2004: 1]).

When I run after a streetcar, when I look at the time, when I am absorbed in contemplating a portrait, there is no I. […] In fact I am plunged in the world of objects; it is they which constitute the unity of my consciousness; […] but me, I have disappeared; I have annihilated myself. There is no place for me on this level. (Sartre 1936a [1957: 49; 2004: 8])

When I run after the streetcar, my consciousness is absorbed in the relation to its intentional object, “the streetcar-having-to-be-overtaken”, and there is no trace of the “I” in such lived-experience. I do not need to be aware of my intention to take the streetcar, since the object itself appears as having-to-be-overtaken, and the subjective properties of my experience disappear in the intentional relation to the object. They are lived-through without any reference to the experiencing subject (or to the fact that this experience has to be experienced by someone). This particular feature derives from the diaphanousness of lived-experiences.

This is close to Heidegger's being-in-the-world. The 'I' is the world, but this world exists in the style of a sentient citizen's chasing of a streetcar. -

The Mind-Created WorldBut this is also why my approach is not solipsistic. When I say the world is 'mind-made' I don't mean made only by my mind, but is constituted by the shared reality of humankind, which is an irreducibly mental foundation. — Wayfarer

Our views aren't that far apart probably. I don't think you are being solipsistic, by the way. And the timebinding human species is the best candidate for a transcendental ego. But consider that this species is part of what it finds in the world. So I'd call it a sine qua non. And what is awareness of...if not the world ? The 'mental,' grasped most profoundly, is precisely the very being of its of 'objects.'

'I' am the there itself. But this is not the psychological 'I' or the person with a credit score. It's vanishingly pure witness, which no longer deserves anthropomorphic trappings, having been recognized as [the perspectival character of ] being itself. -

The Mind-Created WorldThat is how language, mathematics, and all forms of communication are effective - they are part of a 'shared mindscape', so to speak, that have agreed references that we all understand. Or rather, that all those of our cultural type understand. — Wayfarer

I think we agree here. This is Geist, spirit, form of life, culture, the they, one, the who of everyday dasein. -

The Mind-Created WorldI got a copy of Pain and Pleasure by Thomas Szasz, and reads like a work of metaphysics, in a good way. Szasz quotes Russell making surprisingly (to me) phenomenological points that seem relevant to this thread.

When a crowd of people all observe a rocket bursting, they will ignore whatever there is reason to think peculiar and personal in their experience, and will not realize without an effort that there is any

private element in what they see. But they can, if necessary, become aware of these elements. One part of the crowd sees the rocket on the right, one on the left, and so on. Thus when each person's perception is studied in its fullness, and not in the abstract form which is most convenient for conveying information about the outside world, the perception becomes a datum for psychology. But although every physical datum is derived from a system of psychological data, the converse is not the case. Sensations resulting from a stimulus within the body will naturally not be felt by other people ; if I have a stomach-ache I am in no degree surprised to find that others are not similarly afflicted. — Russell

I agree w/ Russell (and Husserl) that we tend to look right thru our own looking. The personal and typically irrelevant how is forgotten in the worldly what. It takes work to really see our own seeing, because such seeing of seeing is even potentially counterpractical. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismFor a fundamental theory the subject and and the ego would have to be reduced. — FrancisRay

:up:

The subject-object duality would be, in Sartre's words, of a functional order only, and the ego would be a fantasy. — FrancisRay

I think my view is pretty close to Sartre's. I'm a fan of his work.

Does it refer to particular theory or approach? — FrancisRay

My influences are blurring together in the phrase, but I'd say that 'neutral monism' and 'phenomenalism' are raw ingredients. I think 'my' view is even part of the tradition, going back at least to Leibniz. It could also be called perspectivism.

'I don't see the world differently. Or this is still not strong and clear enough. I am the world from a different perspective. The world [so far as we can know or even make sense of ] only exists perspectively. ' -

The Mind-Created WorldFor it doesn't matter if I believe that a eating a rotten apple is healthy, the reality of illness will follow. If it were the case that there was nothing underlying to model on, then there would never be any contradictions to the models we create. — Philosophim

I hear you, but we replace one fallible belief with another. I do think you nailed the practical sense of 'reality.' But I don't think you've made a case for the truly independent object (the one from no perspective.) -

The Mind-Created World

:up:the objective world is an abstract theoretical construct, and to arrive at the real, one has 'to put' back the subjectivity that has been discounted. — unenlightened

In other words, the scientific image is (of course, in retrospect?) just a useful image. It's a map that deserves respect, but it's bonkers ontologically -- if taken as some kind of self-supporting independently-meaningful Thing. -

The Mind-Created World

The following analogical argument is obviously wrong (or is it?):

You cannot look at a landscape except from a point of view.

Therefore the landscape is constituted by (or created by) your point of view.

So the question is either: what is the crucial difference in the case of empirical reality in general (as opposed to a landscape) that turns the argument into a good one; or what are the missing premises? — Jamal

:up:

The subjectivist camp is right that the world is always given perspectively, but they don't squeeze enough juice from the fact that it's the world, our world that is so given. Logic is ours not mine. We always intend the one and only 'landscape.'

My mind didn't create our world, but maybe my mind, understood as this world entire but from a point of view, has a genuine if merely supporting ontological role. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismI share an analogy that might help.

ontological cubism

Anyone else ever play GoldenEye on the Nintendo 64 ? It was the supreme first-person shooter of its day.

4 players could each get a 4th of the screen as their POV on the world they shared with the other 3 players. Now this world only existed for those evolving ('moving') points of view.

In the same way, I think our world only exists for or through our own 'split screen' perspectival 'experience.' At least, it's all that we seem to be able to talk about with sense and confidence.

Also this:

https://plato-philosophy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/The-Monadology-1714-by-Gottfried-Wilhelm-LEIBNIZ-1646-1716.pdfThis connexion or adaptation of all created things to each and of each to all, means that each simple substance has relations which express all the others, and, consequently, that it is a perpetual living mirror of the universe.

And as the same town, looked at from various sides, appears quite different and becomes as it were numerous in aspects [perspectivement]; even so, as a result of the infinite number of simple substances, it is as if there were so many different universes, which, nevertheless are nothing but aspects [perspectives] of a single universe, according to the special point of view of each Monad.

And by this means there is obtained as great variety as possible, along with the greatest possible order; that is to say, it is the way to get as much perfection as possible. — link, section 56

The town only exists through and for the monads. -

The Mind-Created WorldWhatever experience we have or knowledge we possess, it always occurs to a subject — a subject which only ever appears as us, as subject, not to us, as object. — Wayfarer

I basically agree. We can only speak with confidence from our actual, embodied experience. We know nothing about a world from no perspective at all. We know the world for sapience. Some have postulated a to-me-paradoxical urstuff, admittedly not without their reasons.

But others postulate too much on the side of the subject. It's the world that is given perspectively, not some private dream. Though dreamers and dreams are also given. Still, language is more social than individual, so we intend always the same world, and that includes the toothaches of others, which figure like prime numbers and pretzels in the same kind of justifications of claims and deeds. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismMy thesis is that if we start with the supposition that there is only one primal stuff or material in the world, a stuff of which everything is composed, and if we call that stuff ‘pure experience,’ the knowing can easily be explained as a particular sort of relation towards one another into which portions of pure experience may enter. — W. James, Does Consciousness Exist?

“Pure experience” is good, but it’ll tempt some to think of an experiencer as primary (or primary in the wrong way, as more than a structural tendency of the stream). “Pure experience” drags the history of its development behind it. Such experience is 'pure' because it is no longer representation. It is not something between a subject and a hidden real world. It is just that which is.

It is a beingstream that includes embedded entities that are for practical reasons often sorted into thoughts and objects, and so on. But these embedded entities are connected like the threads of a blanket. They are semantically interdependent.

A “worldstreaming” is the world given dynamically and perspectively to a subject, which is no longer really a subject but just the being of the world as grasped by a living human being (given perspectively, in the context of motive and memory, etc.) -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / PhenomenalismWhich philosophers in particular? — Wayfarer

To name a few: Kant, Husserl, Wilbur. But the idea, under various names, is at the center of modern philosophy. Wittgenstein is admirably focused on exactly the right issue.

This means that the world's objectivity and our knowledge of it are not simply "given," but are actively constituted by conscious acts. — Wayfarer

In my view, es gibt. The world worlds and being 'streams.' We might say also that time times. As Mach saw, there are lots of causal relationships we can postulate / trace between clumps of neutral elements we call selves and clumps of neutral elements we call cups or X-rays. But I think it's best to interpret 'actively constituted by conscious acts' as the egoic structure of the being stream.

Objects exist in a meaningful context structured by care.

We can’t give a successful or reliable meaning to talk of a non-perspectival 'unexperienceable reality.'

plaque flag

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum