-

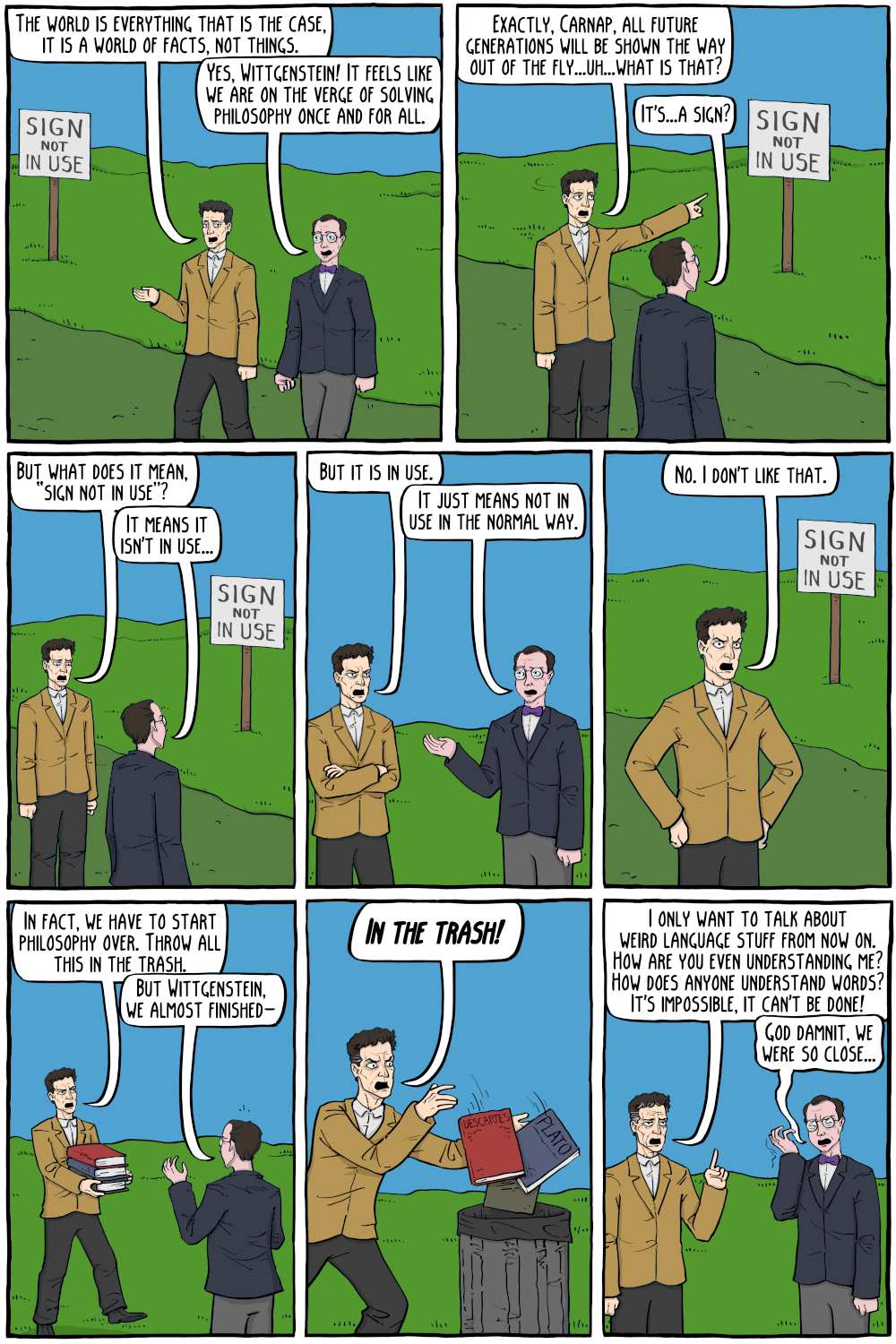

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.True, Kant doesn't tell us that the only truth is synthetic a posteriori, but then neither does Wittgenstein. I mean he doesn't talk in those terms, and neither is it implicit in his philosophy as far as am aware. So, it's not clear what you think you are taking aim at here. The distinction I referred to was not confined to synthetic a posteriori propositions. — Janus

He doesn't talk in those terms (which to me is a problem if you don't acknowledge what came before), but I don't agree that it is not implicit in his philosophy. Empirical observation is basically the kind of "justification" or "truth condition" or "judgement" that equates to synthetic a posteriori in Kant. Tractatus seems to really take the distinction that matters (THIS kind of judgements is SENSE!), whereas other judgements are either nonsense or simply how language syntax must operate. But there is no explanation of how other truths cannot be philosophically valuable (not just POETRY or whatever dismissive thing you give other forms of philosophical writing)..

I agree that there are parallels between what Kant's and Wittgenstein's philosophies, but the foci are quite different, the former being epistemological and the latter semantic, and even in the latter's later philosophy, phenomenological. Both do treat traditional metaphysics as being impossible as sciences of the determinable because both reject the idea of intellectual intution being able to provide knowledge or testable porpositions. — Janus

Indeed, I am at a loss why, when working in academic philosophy, you wouldn't do a much more thorough look at Kant who wrote about this, and is re-writing as if Kant's ideas don't readily address this. In other words, making the turn to linguistics without any EPISTEMOLOGICAL or METAPHYSICAL underpinnings is a bereft endeavor because it is precisely how it is that language can map onto reality, the mind of the observer, and such that is at question, not simply making fiat distinctions between this kind of epistemological justification and that kind of epistemological justification, making pronouncements that those that aren't empirical are nonsense and should be relegated to poetic status or some such nonsense. And again, I know he drops the pretense in PI, but we were talking Tractatus.

The idea of sense and reference incompletely in line with how I was treating the ideas of sensicality and non-sensicality. When we refer to logical or mathematical terms or empirical objects, then we have determinable referents. when we refer to God or Will or Karma or the Absolute, we do not have determinable referents. — Janus

"incompletely in line".. not sure what you meant there. You are repeating what I said, but I was saying that you seemed to indicate it was about what can be "sensed" which is not what he meant by "sense" and thus I was correcting that to my understanding of what he meant.

It doesn't follow however that such non-sensical terms are nonsensical in the sense of being utterly meaningless, to repeat, they are non-sensical only in the sense that they lack determinable referents. Wittgenstein did not reject the ineffable, in fact he accorded it the greatest importance in human life, and that was precisely where he diverged from the Logical Positivists. — Janus

Then Schopenhauer, Kant, Plato, the German Idealists, the French Rationalists, The Berkeleyan Empiricists, even the classic empiricists, should all be considered as valid forms of philosophical writing.. and not relegated as anything else.. My issue isn't simply that he called things nonsense, but the implication that certain things SHOULDN'T be said, because they can only be felt or shown, or revealed or whatnot.. Which of course, flies against much of philosophical writing which does try to EXPLAIN various "non-empirical" ideas.

And then here you are contradicting that Wittgenstein is discounting philosophical DISCOURSE and relegating it to something else.. thus doubling down on his point:

This doesn't seem to me to be the point at all. We clearly can know well enough what we are talking about when it comes to empirical, logical and mathematical matters; with religion, aesthetics and ethics, not so much, because the latter are groundless. We can get each other in aesthetic, ethical and religious discourse, but we do so in terms of canonicity, tradition and feeling, and the subjects we discuss are really ineffable when it all boils down. — Janus

That's my general take on the human situation, and I think it accords fairly well with both Kant and Wittgenstein, insofar as I am familiar with their philosophies. — Janus

Well, I would think because Kant is WRITING in WORDS in explanatory language, his ideas on non-empirical types of philosophical topics, that it would fall under the critique you and Wittgenstein had on such type of philosophical writing. -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.But it was an interesting class. I remember one day one of the topics we discussed wasn't "did Moses exist" but "what would it mean for Moses to exist?" and this still resonates with me. The biblical Moses does A, B, C, D etc. -- according to the Bible -- that is the "biblical moses." But if he only did e.g. A & C would he still be "Moses?" Or what if his name wasn't even Moses but something else but maybe he did "A"? I think this to myself everytime someone says Moses wasn't a "real." — BitconnectCarlos

Is this not a reformulation of the Ship of Theseus? Yes, the analytics were/are indeed caught up on the definition of "is". The Morning Star is the Evening Star right? Or is it?

Identity and essence are the stuff of Plato and Aristotle, the "modern" spin is putting in the linguistic context I guess, and using "possible worlds" for necessity and contingency. -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.

Cool, but I just don’t see the demand for certainty with these concepts as a problem to begin with. They are jumping off points for critical thinking. If one sets up a straw man against all philosophers, one can set oneself up as doing the “real” deconstruction, humbly offering oneself as “just showing the way” (out of the bottle that wasn’t there).

Edit: for example, Schopenhauer’s WWR isn’t because he is frightfully uncertain about reality (perhaps Descartes used this thought experiment but I can probably defend that as well simply as a tool), but rather using ideas from Kant and eastern philosophy to answer various questions, presumably knowing words are mere words but can still convey ideas that can elucidate the subject without being stated of affairs thus empirically verified. -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.Language lacks the precision and exactness that the philosopher expects and demands of it. It is not language itself but this misunderstanding of how language works, this particular picture of language, that is what has bewitched philosophers, including the early Wittgenstein. — Fooloso4

I see that as a broad-reaching strawman for all philosophers in general. For example, how could Schopenhauer not be aware of the ineptness of language to capture something like Nirvana, or that the world is both unified and individuated? These are inherently contradictory concepts. That didn't "bewitch" him, but rather he just sought out various ways to explain it in both Western notions and (newly published) Eastern notions.

Witt is solving a problem for many philosophers, that simply wasn't there to begin with, EXCEPT for certain ones demanding various forms of rigorous world-to-word standards.. And those seem to be squarely aimed at the analytics, if anyone at all. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankTo be clear: removing hundreds of thousands of settlers to create a Palestinian state is something you consider realistic, correct? — Tzeentch

Yes, give or take, and that again was the basis for the 2000 negotiation, with large swaths of settlers to be removed.. and not sure, but Pals would have had at that point a lot of infrastructure to work with.. Like Gaza, probably kept things intact, but in Gaza the greenhouses and infrastructure was destroyed.. Lovely. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankIt was after the Sinai debacle that Israel actually vowed never to conduct such a removal again — Tzeentch

Which they did in Gaza afterwards, so that was false just on the events.. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankAgain, what deal are you talking about? There was no deal to be had. Or do you think Israel would have started removing settlers based on whatever borders were agreed? — Tzeentch

If Israel couldn’t remove settlers then you could legitimately have an argument that Israel was in the wrong. You first need the agreement for that to even happen. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Barak and Morris were in accord. Barak wasn’t going into the deal in bad faith, he wanted to finish the job of Rabin. Clinton wanted a legacy. Arafat didn’t mind more violence for a non starter issue. -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.There's a valid distinction between propositions which can be confirmed or disconfirmed by the senses, and in accordance with the ways in which we make sense of experience; namely, causality, logic and mathematics, and aesthetic, ethical and metaphysical judgements or beliefs, which cannot be decided in those sense or rule-based ways.

The former understandings which are consistent and coherent with those sense-based modalities and the massively complex and mostly coherent web of understanding that has evolved by virtue of those ways of making sense, are readily distinguishable from the other kinds of undetermined speculations based on aesthetic, moral or religious intuitions or desires or fears or anxieties, with the former appropriately being named 'sensical' and the latter non-sensical.

The implication there is that the latter are not clearly related to the world of the senses, or the causal, logical and mathematical understandings which have evolved from the experience of that world. And I take 'non-sensical' in this context to indicate that difference in distinction to 'sensical', and not to be a declaration that such speculations are utter nonsense, or worthless, which they clearly are not, any more than poetry is or moral attitudes or aesthetic judgments are. — Janus

But we all know this distinction. We didn't need Tractatus to tell us this.. in fact, Kant did an excellent job spelling out the differences in possible justifications for "truth" conditions.... To focus on synthetic a posteriori truth as somehow the only one that one "meaningfully" discuss, is the very point that needs to be contested..

It's a sleight of hand to say that "there is a distinction between synthetic a posteriori truths and other types of truths (which everyone can probably agree to some extent)", and somehow use this obvious point to posit, "ONLY synthetic a posteriori truth is meaningful in linguistic terms".. That there is a distinction doesn't mean THUS it is meaningful.

Also, your use of "sense" here I believe, is playing around with the term "nonsense".. Nonsense does not necessarily mean "non-sensed by the five senses", but more in the Frege "sense" of "sense" and "reference". That there is a cat on the mat has a reference, because it can have some empirical element of verification (not simply that you can sense with your five senses.. that is something more along the lines of Mach perhaps, which @013zen can elucidate more on.. that you literally need some direct empirical verification from observational evidence and not just a model from that evidence)..

But anyways, there is nothing he is proving such that language cannot be meaningful if it is discussing something that has no direct reference by way of empirical a posteriori means.. That is to say, there can be truth to "reality" that is beyond this, and it can be discussed, and discussed without leading to confusion.. Rather, terms have to be more clearly defined, etc.

Now, Wittgenstein does come around to this conclusion in the PI, that it depends on the use of the word in a language community, but that beyond public use, the word can get misunderstood, and it would be hard to discern if anyone is really "getting it" other than the public use of it.. This seems like an obvious reality to me, though I guess his exhausting examples of language breakdown just hammer the point home.. But that being said, no one is contesting that human communication is almost impossible to be 100% clear or meaningful, because it is impossible to get in someone's head and go, "OH YOU REALLY GET IT!". .Rather, you can never truly know beyond public displays that someone's inner understanding corresponds with their public use.

I'll add -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Read the article. Arafat got what he wanted.. The right of return, other than small numbers and compensation or some combination, was not going to happen.. At some point, you take a deal because it's good for your people to move forward. He didn't and caused a second violent "shaking off".

And you saw the rightward shift after that.. Hamas blew up shit during the 93-00 accords not because they had differences in minor details.. They hated the Jewish presence in the whole region.

It's Hamas caused enough violence to think that Arafat couldn't have control of his more violent wings, and when listening to him in Arabic was encouraging it .. Israel still negotiated and got more violence and that's what they remembered. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Considering the historical precedent of Jewish death in Europe, Western backing of a Jewish state would seem part of a post-WW2 reality.. In whatever form that takes.. Combining the years of medieval hatred, Dreyfus Affair, pogroms, inquisitions, the holocaust and anti-Israeli Leftist sentiment and you get a quite ridiculous judenhass. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankWhat realistic prospect of a Palestinian state are you even talking about? — Tzeentch

The 2000 one.. where 92% of land was contiguous. It was the best deal they could get, and the best Arafat could say was it didn't include right of return, so no deal and no counter offer.. Read this article for most accurate understanding:

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2002/may/23/israel3

Benny Morris is often cited as the standard for history on this conflict.. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankWho decides this? Why is it off the table? Because Israel says so? It's a negotiation. Nothing is off the table. — Benkei

Yes some things are non-starters. If the religious right demanded that all Jews have right of return to their ancient homeland of Judea and Samaria you’d probably say that’s a non-starter.

And that's how Israel usually blocks every progress by putting demands on the table before negotiations even happen. And you happily go along with it because you obviously have zero experience in negotiations. — Benkei

No Palestine has blocked their own progress because they never accepted a Jewish state in any variation since the Peale Commission..lost every war that would make it a reality, and then from a position of having lost make demands 45 years later to effectively dissolve the current contingent demographic majority of a Jewish state. The Palestinian leadership certainly failed big time at negotiations..They had Clinton backing them, everything set to get their nation states, compensation for refugees, ln and exchanges, East Jerusalem, etc. they had a prime minister who was bending over backwards based on the politics of the time. -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.Well you hit the nail on the head with this. Unapologetically arrogant. And, on the face of it, inexplicably so. It comes off as personality, but there is something to be said. In the Tract he had a desire and an imposed standard for every statement. He would only say what he could be sure of, certain about (a la Descartes)—so it has a dictatorial ring. What he learns through the PI is that this singular requirement (before starting; an imposed pre-requisite) of what he would allow himself to state, narrowed his topics and what he would see/could say. In the PI, instead of imposing a requirement, he is looking first (investigating) for the requirements (criteria) that already exist, each different, for each individual example (their grammar/transcendental conditions, e.g., of: following a rule, seeing, playing a game, guessing at thoughts, continuing a series…). — Antony Nickles

Yes I understand, but nice summary of thinking of Tractatus and the move to PI... -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.It's not so much a matter of the answers to such questions not being able to be true or false, but about our ability to establish definitely the truth or falsity of them, as we can when it comes to (at least some) empirical, logical and mathematical questions.

The point is that we know what evidence looks like in those last-mentioned domains but have no idea what could constitute definitive evidence for the truth of aesthetic, ethical, moral or religious assertions. — Janus

That doesn't make it "nonsense" though. It doesn't make it any less legitimate to "philosophize" about. It is arbitrarily marking out what philosophy is allowed to be called "sense" and "nonsense". As I said earlier, you stack the premise a certain way and of course your conclusion comes out that way, but not justifying why that premise makes something "legitimate" or more specifically, "sense", and another not, is simply asserting your own preference for the premise.. and wouldn't you know it, there was a whole movement starting with Frege that was a ripe audience for such views.. gee whiz. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankGiving up the land you legally have a right to is not conceding the hard stuff? — Benkei

That wasn't really the thought process before 67 or in 48, so yeah...

Why don't you explain to people who actually lose their homes, families, community and culture what else they should give up on to really get to the "hard stuff"? — Benkei

Right of return is off the table. It's a non-starter and he hung his hat mainly on that, and you can add a few other irrelevant things..but it was mainly that hat.. Using a peace deal to indefinitely try to get more in your favor when you have no state apparatus in the first place was not a great move. He had a chance, and let it slip through his fingers (and that is being too gracious.. I'm sure he never meant to settle a deal), and encouraged the "Second Intifada" pushing people like Barak away, promoting the Israeli right's move for "security" and sealed the fate of the peace process for years.. -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.Does the irony of all this escape you? Wittgenstein is not to blame for your asshole tendencies. Across multiple threads I have attempted to discuss Wittgenstein with you as I understand him. In response you have called me a "fanboy" and other things including now accusing me of playing coy. — Fooloso4

I'm not sure if it's the philosopher or the adherents but Wittgenstein's whole Tractatus is to prove that some philosophical writing is nonsense.. so you can say that I'm an asshole or whatever, but relegating whole swaths of philosophy as "nonsense" is a pretty damn asshole move.. And then you deny that it applies to pretty famous "nonsense" philosophies (ACCORDING TO HIS IDEA OF NONSENSE)>...

And yeah, denying that his NONSENSE idea applies to various philosophers of metaphysics (like Kant), is playing coy.. so yeah....... -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.The contention is that they don't. When people talk about God there is no one thing that they are all referring to. No one thing they all mean. — Fooloso4

That's fine.. It's up to the writer to then explain the historical context and use of the concept...

I think he might be following Kant with regard to making room for metaphysics as a matter of practice, of how you live. — Fooloso4

But Kant TALKED about (at the least) epistemology, and Noumena as metaphysics.. and things that cannot be empirically proved or disproved.. Don't play coy here.. Kant is WROUGHT throughout with non-empirical ideas that can't be "proven" scientifically but are the FOUNDATIONS for thought itself! -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.The philosophers write for those who already have faith in philosophy. Peer reviews, , publications in books, journals and pamphlets (the old-fashioned ways). The one that could be in a position to critique another's theory or hypothesis is no other than the philosopher himself. — L'éléphant

No, what I meant was he was writing for a very specific set of philosophers, who more-or-less held views regarding "nonsense" and things outside the scientific purview in regards to language use.

Though later on, when they tried to make his work as a great work advocating for the abolishment of various philosophical schools of thought... Wittgenstein, whilst agreeing in one sense, did not want to diminish poetry, religion, etc..

The fact still remains that as far as WRITING about PHILOSOPHICAL topics, he thought that various things that were not talking about empirical statements, were not to be taken seriously as philosophy proper.. I see it as evaluative of other philosophical types of thinking that weren't empirical-based.. discussing scientific observations, etc. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

-

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.Those are the people he is addressing, the people he is engaged with. — Fooloso4

I would think a philosophical position would be more than simply having the acceptance of one's social circle..

Right. Unlike the facts of natural science. — Fooloso4

What makes them then have "sense" in language? That is my contention.. That he thinks if it doesn't have empirically valid outcomes it is "nonsense".. He is arbitrarily delineating language that way, and for his friends apparently...

In the Tractatus Wittgenstein distinguishes between philosophy and natural science. Philosophy is not about the facts of the world. — Fooloso4

He clearly thinks that philosophy entails a lot of "nonsense"..

Does he think a philosopher like Kant is a valid form of thinking about reality or not, is the question.. We can go around in circles..that it's useful nonsense or protected nonsense.. but there is something he is trying to say about philosophy that is not centered around the empirical.. I wonder what that is.. can't be disparaging at all... -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.I don't know if you miss the point or are just being argumentative. If a term is used in more than one way then if we are to understand an author we must understand how they are using particular terms. This is not something unique to Wittgenstein. That is why some editions and discussions of a philosopher's work includes a glossary. — Fooloso4

No I am not being argumentative, but I am saying it is precisely justification for "why science/empirical" as the definition that is not explained. Thus why should I take the conclusions as relevant, if I don't have a clear understanding of why he chose those premises that lead to those conclusions?

It can lead to confusion or nihilism. — Fooloso4

I don't think people who discuss, defend, or engage in those theories think that. Seems like a strawman, or a solution to a problem that does not exist except for certain people who deem it so (Russell, Mach, Vienna Circle, etc.).

You might argue that it is either true or false that God or the Good exists. Are you able to determine and demonstrate to the satisfaction of others whether it is true or false? — Fooloso4

That is really subjective. Someone might find it convincing, another person may not. The key here is "the satisfaction of others".. What "others" are we to say must count as having to be satisfied?

The bigger point from this is, much of philosophy relies on the basis of thought, which goes beyond what can be proven empirical.. There is no reason or sense in limiting philosophy to only one aspect of the outcome of how our senses evaluate the world. Rather, we can also examine the conditions behind the outcomes (experiments/observations), the conditions for truth itself (mathematical, empirical, logical, or otherwise), what "free will" is, what "subjectivity" is, etc. etc.

There is nothing in the definition of "philosophy" or "language" that demands that they preclude non-scientific topics that are to be analyzed and evaluated in various stringent, and rigorous ways... -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankCorrect. They just reject the PLO as their country has been all the time rejecting any Palestinians that have talked about a two state solution. Netanyahu has been quite successful in this. — ssu

But you must admit, with Arafat and Abbas, there is more than a bit of gaslighting with saying "two state solution" but not making the hard decisions in a position of relative weakness comparatively (being their allies and them went to multiple wars and were basically defeated.. and in those wars did not have the aim of having a state so much as eliminating the existing state of Israel, and only recently as of the 60s really making it about forming a strictly "Palestinian" state rather than an enclave on a greater pan-Arab goal (whether that be "greater Syrian, being part of Jordan or Egypt, split into various internal groups, or its own entity of Palestine, West of the Jordan.,, -

Are War Crimes Ever Justified?

I am trying to understand your own paradoxes here..

You seem to agree that Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan had the right to be put in a position of total surrender, no? For the perspective of the US, let's say, there were only 2,403 people actually killed in a sneak attack. Did that mean Japan should suffer many thousands to millions of deaths upon the end of the war? And if the tragic answer was, "Yes, because Japan would keep trying to expand, retaliate and become even more aggressive", then look at how a) 2,403, turned into b) millions of death for Japanese.

And there were around 111,000 Americans that died let's say, just in the Pacific theater. Lower percentage than Japanese, but if the Americans had a way to keep that number lower but still maximizing efforts against Japan, do you not think they would, if they had the advantage? Just having a greater force for example, and using it to defeat an enemy that unwisely decides that you need to be "eliminated from the map", doesn't confer that the bigger enemy shouldn't try to defeat the weaker one for foolishly attacking.. In fact, one would think the smaller army would not attack precisely because the enemy were bigger and had the potential to use their bigger force, and that would be a preventative measure for attacking the country directly in the first place.. (Not the case in Vietnam, for example, because that was a civil war that the bigger country tried to "help" in, not really an a country sneak attacked and then declaring a state of war with that country.. it was a limited military action comparatively..and same even in Iraq and Afghanistan.. If the US mission was utter an total surrender in the same terms as WW2, then we would be talking very differently about the aims and outcomes of that war.. In fact a greater discussion could be had about what it means to have a limited war and its general failures even).

So I guess my bigger point is that we see that war itself means death and destruction, and not just of soldiers involved, then how can war be legitimate, even as a defensive action against an aggressor, like one that does a sneak attack, when we know that horrible outcomes are the result of going to war (especially total wars that are about making the other country's leadership completely surrender)...

I say it is the 18th and 19th century that might be the aberration due to the technology of the time.. But you also look a little closer, internal politics might have been much bloodier.. The English Civil War preceding that time and the French Revolution were bloody as hell...And even in the 17th century, the bloody and deadly Thirty Years War... -

Was Schopenhauer right?That seems right to me...it is simply being without getting caught up in conceptual notions of "ultimate reality". I guess the point is that ideas can never be reality, because they are inherently dualistic. Easier said than done, though. — Janus

Reality for Schopenhauer, if it's based on Kant's framework, can never be "known" except the appearance of a thing on our cognitive apparatus...Schopenhauer posited that we can infer that there is Will based on our own subjective aspect which is will manifest in ourselves, through construct of a subject-for-object, with the appearance/representation/phenomenon the aspect of subject-object mediated through the subject's faculties of space, time, and causality imposed upon the object. -

Was Schopenhauer right?@ENOAH @Wayfarer, You might enjoy this. It's an old paper (1911), but its intro condenses Schopenhauer's ideas well in a few paragraphs:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/27900310?seq=1 -

Wittgenstein the SocraticI like to think more in terms of insights than in terms of views. (Metaphysical) system building I see as a strange for of poetry, and exercise of the imagination, a game not to be taken seriously once you realize that a metaphysical view can never be the truth but is rather just a possible way of imagining things to be. — Janus

Ok, so the supposedly "open doors" of Wittgenstein is quite closed in your mind in terms of imaginative possibilities for reality...

I don't understand knowing yourself as a matter of "constructing views"...quite the opposite; I think it is a matter of relinquishing views, and the need for certainty that motivates them. — Janus

No, again here you are putting it opposition. It could be both.. Construction, critique, new construction, etc... At some point, you make a case. Hell, even Wittgenstein is supposed to have a point somewhere in his "showing"... So you go one step further to the skeptical...

I don't know what you are referring to. None of what you are saying in that post seems to have any bearing on what I had said. If you care to explain how it relates to specific things I wrote, that might help. — Janus

A lot of people, it seems including yourself, like his style which I described, and I was saying what my problem is with this. -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.Propositions, as he uses the term — Fooloso4

Sure, and I can use the term a different way..

re about the facts of the world, the facts of natural science. — Fooloso4

Exactly! You start with a premise you get a conclusion. What is to say you cannot use a different premise as what "facts about the world" are and thus a different conclusion? It's a preference for discussing reality in terms of empirical findings using a certain institutionally defined method...Of course if I started with those fiat assumptions I would come up quickly not only with the conclusion of Tractatus, but with quite the opposite notion (that it's basically how you use the words in a language community) in Investations.. It seems like a big conversation he is having with his own views...

They are either true or false. If something cannot be determined to be either true or false, as he thinks is the case with ethics/aesthetics, then it does no good and potentially much harm to treat it as if it were a linguistic or propositional problem. — Fooloso4

Why would it do "much harm"? But the bigger question, and the one that's more important is why non-scientific/empirical kinds of questions cannot be true or false.. Different criteria can be used, for example, as to what counts as "evidence". But this to me seems so strikingly apparent, I am not sure why it isn't brought up more against his case and thus I ponder what the big deal is... If your sentiments on things are (haughtily) in line with his ideas to begin with, then it's just a big "Yeah I think that too!" echo chamber, but no real justification for why science/empiricism. In fact, if he spent any/more time on that and not simply the assumption of that, perhaps we would be having a different discussion! -

Are War Crimes Ever Justified?

Just let me know if you know where you think I'm leading here... -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.It is not a matter of what language needing protection from but of what is off limits when language is restricted to facts. In the Tractatus Wittgenstein holds to this restriction, but this means that ethics and aesthetics are not propositional problems. They are experiential not linguistic. — Fooloso4

Contra whom? Not Hume.. ha.. but really.

You know where this is going...

By what authority can you limit sense versus nonsense? What standards...

Who is he explicitly against here? Other philosophers (like the German Idealists, Dutch and French and German Rationalists, certain Empiricists, the Platonists, Medieval philosophers of various sorts).. would that be correct?

"What" would count as propositional anyways without being self-referential? States of Affairs (what counts as states of affairs) are not self-evident.. without simply defining so by one's particular fiat "so I proclaim!".

That is to say, if I defined states of affairs as X, Y, Z, certainly my conclusion would thus come out a certain way.. That is only if I define states of affairs as X, Y, and Z, which besides personal prejudice/preference, doesn't seem to have a reason to be defined such and such way and not another way, one which might lead to a different conclusion.

And so on... -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.Answers to what questions? — Fooloso4

Stuff relating to language -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.In the Tractatus he follows what others said regarding facts and propositions, but by doing so he left open and guarded rather then forced closed the problems of life, beauty, and what is higher. — Fooloso4

What does this even "mean"? And I'm being serious. Can you explain, and not cutsey-koan "show" me.. I indeed ask you to just tell me what you meant there. What does language need protecting from? Because the use of "nonsense" itself seems to imply various things that HE created/expounded upon from others...

Edit: In other words, it seems like a problem (nonsense) that didn't even need protecting... -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.Forms of life have more to do with might be called his anthropological turn than with linguistics. — Fooloso4

Yeah, and so I look to anthropology for those answers.. I'll give credit to pointing there though.. if not explicitly.. -

Are War Crimes Ever Justified?By the fact that the victors of wars lay down the post-war laws. As I've stated earlier, the commander of the RAF Bomber command has acknowledged that if the UK would have lost the war, he would have been convicted of war crimes. — ssu

Right, good quote.. So can you see where the implication I am going with this is? I am talking about Wittgenstein and not directly stating something in another thread.. but unlike him, I am not trying to give you a never ending transformative methodology that you need to "get".. just a leading question.. but do you know where I am leading? -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.

I'm going to not go out on a limb here and defend .. Where as Socrates directly addressed pertinent issues of ethics, metaphysics, and epistemology, Wittgenstein was hampered by his own need to appeal to the linguistic turn, thus relating everything to either "sense" vs. "nonsense" as to how language was employed or "use" and "forms of life", and the inherent breakdown of various usages of words in different contexts. This already draws from a more shallow pool, or at least tethers one to a more shallow pool, and it leads to pedantic pointing out of how language can lead to confusion, which I am not sure was not pointing out what was obvious for the common reader.. It seems more transformative if you drank the analytic kool-aid beforehand, but then that also makes the readership more shallow, and less relevant.. And then the conclusions become again, not interesting beyond the exercise in watching various ways he attempts to show language working or not working.

And my basic premise stands here:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/906391

I think that might be where Leontiskos is coming from.. And again, I would tend to agree.

And I get it, the big canard is "YoU JuST DoNT GeT HiM!!" But that is the point.

I can employ his method of indirectness.. I can implicitly demand that you need to read into my writing, and that I have a methodology, and once you get it, you will be transformed.. And if you are not, you just don't understand enough yet.. but that is Appeal to Prophecy... And at that point, it becomes an Appeal to Popularity as to how legitimate your Appeal to Prophecy should be deemed.. which I also don't think is legitimate. -

Wittgenstein the SocraticWhat could the value of metaphysical speculation consist in if not to show us that metaphysics is undecidable, and not a matter of reaching some theorem which is guaranteed to be correct by rigorously following the rules? The analogy with mathematical exercises seems quite weak to me. — Janus

Why are you making this a "one or the other" scenario? Some of philosophy is to critique a position, and some is to construct it. However, I am just saying "critiquing" a position (whether in an argument or open-ended question) is just one part of the process. At some point it is good to construct one's own views.. "Know thyself!".

Also Socratic Method is good as teaching tool, but if it is done as some "method" of indirectly expressing your (constructive) views, this to me seems to be a bit of bad faith. What if all philosophers spoke in this "indirect" way such that every time you read a Russell or a Kant or a Kripke, instead of the author intending you to understand him (and maybe failing with their writing style), they MEANT to MYSTIFY you.. I think that would be ridiculous as far as how humans should communicate in good faith to each other.. A little is ok.. but if all your philosophy is meant for YOU to de-mystify MY philosophy, without ME being the one with the burden of explaining MY philosophy, I think that is arrogant.

See here: https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/906391

And if you say, "Mystification?? No dear sir, it is a STYLE and METHOD.. You just have to "get it".. the same thing applies.. It's not up to the reader to understand YOU, but for YOU to communicate to the reader. However much you think you are a sage worth deconstructing. -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.I can only say that he is writing to a particular audience (certain philosophers), as embodied by the Tractatus’ (his previous) rigid, imposed requirement for judging whether we are saying anything. Given this fixated intransigence, he is now (in the PI) resorting to any means necessary to break that death-grip hold for knowledge (certainty) to take our place (the “picture that holds us captive” PI, #115). Thus the questions without answers, the foil of the interlocutor, the riddles, the… indirectness. He is doing this because he feels that philosophy needs to be radically revolutionized, and so his style, as Cavell puts it, “wishes to prevent understanding which is unaccompanied by inner change”, i.e., change from the position we are in (philosophy has been in), our “attitude” (see above), how we judge (our “method”). — Antony Nickles

Do you realize why both the Tractatus and the PI come off as infinitely arrogant?

And if you cannot answer, then I ask you to

Thus the questions without answers, the foil of the interlocutor, the riddles, the… indirectness. He is doing this because he feels that philosophy needs to be radically revolutionized, and so his style, as Cavell puts it, “wishes to prevent understanding which is unaccompanied by inner change”, i.e., change from the position we are in (philosophy has been in), our “attitude” (see above), how we judge (our “method”). — Antony Nickles

So I am not going to explain anything to you from now on.. I want you to interpret my indirectness, as otherwise you will not be transformed :roll:

And mind you much of philosophy is arrogant-adjacent.. like the asshole, is the arrogance the product of the person, the context, or the activity?

Look at me with my questions! I must be a zetetic skeptic practicing maieutics. -

Are War Crimes Ever Justified?A legitimate war is if you are attacked, you can justifiably defend yourself. Even the Old Testament in the Bible says so (not the New Testament, and not surprisingly). Nobody can say that you were the aggressor, however times the aggressor will declare "that he was forced to do it". Many would also see as legitimate an intervention to some heinous genocide or civil war. Like Vietnam isn't accused by the World community in ending Pol Pot's reign of terror. — ssu

Agreed

Then, if you don't do warcrimes, you don't have any skeletons in the closet (literally...) that you try to hide away. You can have a clear consciousness about the war and that you fought in it. — ssu

I just want you to juxtapose that with this:

Again I would recommend reading Clausewitz.

When attacking the US at Pearl Harbour, Japan likely assumed that the US "would see" the writing on the wall and simply negotiate some peace with Japan and leave it alone, which the Japanese would have gladly accepted. Yet (domestic) politics in the US didn't go that way. Just as mr Hitler didn't see what a huge error he made with declaring a war with the US.

But hey, Americans were simply lazy racists with an army smaller the size of Belgium, so what kind of threat could they be? That was the idea of the US that the Nazis had. — ssu

It seems here that Nazis and Imperial Japan had it coming, even though Japan only killed 2,403 people as far as attacking Americans.. But the millions lost aren't presumably considered a "war crime". How can you square that circle? I am trying to look for double standards and blind spots in arguments that lead one to say "Heads I win, tails, you lose" as another poster put it about another argument.

[Note: Adjust the numbers to what you want.. the point being that the magnitudes are much greater, the end result of the death from the initial attack which both of us can probably agree was justified in starting a defensive response].

schopenhauer1

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum