-

Claim: There is valid information supplied by the images in the cave wall in the RepublicDefinitions that are created by physicists. — Wayfarer

You were quoting physicists as supporting your argument.

And measurement is a conscious process.

Scale and perspective likewise imply a point of view, because you can’t have either without a comparison.

Recall that we’re speaking about ‘things as they appear to us’, not ‘things as they are in themselves.’ That is the fundamental point in this conversation. — Wayfarer

So the Earth appears to be 4.5 billion years old but isn't really?

The human point-of-view is a relational one (i.e., between natural systems, of which a human is one) and does not depend on a Kantian phenomenal/noumenal distinction. -

Claim: There is valid information supplied by the images in the cave wall in the RepublicHe explicitly states ‘an observer with a clock’. — Wayfarer

In a physics context, an observer is "a frame of reference from which a set of objects or events are being measured", not a reference to mind.

It's useful to separate the idea of the reference frame of a system from the idea of the consciousness of a system. Time is reference frame-dependent, not mind-dependent. Which is why it is coherent to say that the Earth aged prior to the existence of human beings. -

Claim: There is valid information supplied by the images in the cave wall in the RepublicWhat I’m arguing is that time itself, the sequential ordering of events along a specific scale, is grounded in the mind. That’s the import of the passage I quoted from Paul Davies:

"The passage of time is not absolute; it always involves a change of one physical system relative to another, for example, how many times the hands of the clock go around relative to the rotation of the Earth. When it comes to the Universe as a whole, time loses its meaning, for there is nothing else relative to which the universe may be said to change. This 'vanishing' of time for the entire universe becomes very explicit in quantum cosmology, where the time variable simply drops out of the quantum description. It may readily be restored by considering the Universe to be separated into two subsystems: an observer with a clock, and the rest of the Universe. So the observer plays an absolutely crucial role in this respect. Linde expresses it graphically: 'thus we see that without introducing an observer, we have a dead universe, which does not evolve in time', and, 'we are together, the Universe and us. The moment you say the Universe exists without any observers, I cannot make any sense out of that. I cannot imagine a consistent theory of everything that ignores consciousness...in the absence of observers, our universe is dead'." — Wayfarer

Davies is referring to the world, not mind, when he says, "... how many times the hands of the clock go around relative to the rotation of the Earth."

The only reference to mind or consciousness is Linde's claim in the second-last line, but that doesn't follow from anything he or Davies said in that passage, the import of which is that time is reference-frame dependent. That is, time does not apply to the universe as a whole, it applies to subsystems.

For an explanation of how time vanishes for the universe as a whole, see Quantum Experiment Shows How Time ‘Emerges’ from Entanglement. -

The HARDER Problem of ConsciousnessIf there is no hard problem, we should be able to reach scientific or philosophical consensus on those types of questions. — Marchesk

There is lack of consensus whenever testable hypotheses are absent. One of the consequences of that absence is language on holiday which is what dualism is.

Consider the opening sentence on Wikipedia for the hard problem: "The hard problem of consciousness is the problem of explaining how and why sentient organisms have qualia or phenomenal experiences ..." (italics mine).

You can see how dualism is built into the problem statement. Remove the italicized words and the problem becomes the much clearer one of explaining sentience - something that scientists can work with. That is, differentiating sentient creatures from non-sentient creatures (which we can point to) and providing testable hypotheses for explaining those differences.

Right, dualism is just one possible answer to the hard problem. — Marchesk

So my claim is that dualism is the root cause of the hard problem.

I see your argument as not advancing anything other than what we know. People experience quale, we can converse about it. — schopenhauer1

People converse about ghosts too. I'm suggesting that if we seek to define the problem in natural language then the ghosts will eventually fade away. See my reply to Marchesk above. -

The HARDER Problem of ConsciousnessThis is muddled. WHAT is the "qualitative state" then? That is the hard question. Qualitative states exist, you are proposing. I agree. — schopenhauer1

We can be in pain or see green objects - that's just everyday, conventional experience. However there are no radically private qualitative states, or qualia. We simply interact in the world (that's our experience) and develop public language for the things we interact with.

By saying they have a different referent, you are just restating that it appears to be a different phenomena. How is it that these two things are related, or are one in the same though? Hence the hard question. If they are not related, then you still have the question, "What are the qualitative states"? What is quale, as compared with the scientific explanation that causes or corresponds with quale? — schopenhauer1

See above regarding qualia. How some things we point to (such as green grass) relate to other things we point to (such as light), just is what science seeks to explain. And as I argue here, that provides a human view of the world, a relational view, not a "view from nowhere". As such, knowledge about the world provides insight into ourselves.

The problem, as it is, is simply that there is not yet adequate language for what you want to explain. It's the beetle-in-a-box. Co-opting existing public language and giving it a private interpretation doesn't help, it just muddies the waters. As we've seen with modern physics, it's continued scientific investigation that exposes hidden assumptions and forces us to rethink the kinds of questions we're asking and whether they even make sense.

It's been the human experience since at least philosophical inquiry began and the distinction between appearance and reality was a thing. — Marchesk

Yes, things aren't always as they seem. We agree on that. However the distinction doesn't imply dualism (i.e., of ontologies or worlds). Adopting dualism is a philosophical choice. -

The HARDER Problem of ConsciousnessThen what's an example of a solution? Or do we just not debate philosophy of mind and problem solved? I don't see how the problem is not a problem by using different language, or rather, I don't even see how that language would be employed. When I say "green" as a qualitative state and "green" as a wavelength of light hitting the eye and producing all sorts of neurological states and arrangements, they seem different. How would you suppose to not have the difference without adding the ghost? — schopenhauer1

"Green" in its ordinary public sense is not a qualitative state, it's a property of certain objects that human beings can point to (trees, grass, etc.) There's a qualitative/experiential aspect in the pointing, but not in the objects.

The scientific usage of "green", while related, has a different referent (i.e., we're pointing at something else, namely a range of light wavelengths).

As I see it, problems are solved by differentiating our experiences, developing a public language around them, and generating testable hypotheses. That is what scientists (and to some extent all of us in our everyday lives) do. The philosophers' role is to resolve/dissolve the conceptual problems that arise.

I just don’t buy that language is the problem here. I have pain and color experiences, but those aren’t part of the scientific explanations of the world or our biology. And language doesn’t create pain or color experiences. Rather, they are simply part of our experience which language reflects. This leaves color and pain unexplained, with no way so far for us to reconcile with science.

Language is dualistic, because that’s our experience of the world. — Marchesk

That's not my experience (nor, I think, anyone else's). And its not clear to me what you think medical science is doing if not investigating the causes of pain and suffering.

You and I seem to carve up the world differently despite using similar-sounding words. That's a language issue and it affects how we perceive problems such as the "hard" problem. -

The HARDER Problem of ConsciousnessYes, I see this type of phrase a lot of rejecting the "Cartesian" conceptualization. But exactly does that mean? The hard problem still remains. It seems to me a sort of de facto panpsychism perhaps. I don't know. — schopenhauer1

It's not panpsychism. We're only talking about sentient creatures here. The problem is that in the Cartesian scheme, we're non-sentient creatures plus a ghostly bit. Or p-zombies plus a subjective bit. But that's not a natural way to conceptualize human beings. It's a dualistic way.

A lot of philosophical language is implicitly dualistic. And it can make problems look more intractable or mysterious than they otherwise would be. -

The HARDER Problem of ConsciousnessImmediately I would see that the first person ontology becomes the "ghost in the machine" that he purports to reject. It is exactly that question of how micro-states (third-person) IS or BECOMES (is over time) macro-states. Just to say "we have micro-states" and "we have macro-states" is to simply restate and beg the question. — schopenhauer1

I would agree. It's the ghostly "first person ontology" that needs to be rejected. And that doesn't then imply a "third-person ontology", which would just be the (behavioral) machine half of the "ghost in the machine". The Cartesian conceptualization needs to be rejected entirely, both in whole and in part. There is just ontology that we flesh out in (public) language, whether ordinary or specialized. -

Illusionism undermines EpistemologyStick a pin in your arm and see if you still think that pain is an illusion. — Banno

There was a faith-healer from Deal,

Who said, ‘Although pain isn’t real,

If I sit on a pin

And it punctures my skin,

I dislike what I fancy I feel.’ -

Illusionism undermines EpistemologyIf we perceive the world as colored in, and science explains it without the coloring in, then the appearance of color needs to be explained. It doesn't matter whether we call colors relational, qualia, secondary qualities, representations, mental paint or whatever. Changing the language use isn't going to help. — Marchesk

There aren't straightforward word-for-word translations - those words have different uses in various philosophies and tend to have a cascade effect onto the use of other words. A case in point is with the terms "experience" and "consciousness" as evidenced by this thread.

One might think that neuroscience or biology would be of help here, but the coloring in isn't found in explanations of neuronal activity or biological systems either. This is why we have questions about whether other animals, infants, people in comas, robots and uploaded simulations are or could be conscious (experience a coloring in in their relation to the environment). We can ask what or whether it's like anything to be a bat or a robot using different terms, and the same issue arises. — Marchesk

You can ask the same kinds of questions about length, mass and time which we also perceive in particular ways. Philosophers can take the concrete findings of science and attempt to untangle the conceptual issues, but it's still up to scientists to do the hard work of investigating, differentiating experiences (such as with the honey sweet/bitter example), and coming up with explanatory models. -

Illusionism undermines EpistemologyScience is an objective, third person enterprise that abstracts away from individual perception to formulate equations, models and laws. This is fundamentally based on the realization that properties such as extension, shape, mass, composition and number belong to objects, allowing us to systematically investigate the world and form predictable explanations. — Marchesk

And that realization or perspective is a human one (i.e., it's based on the kinds of creatures we are), not a God's-eye perspective.

It's not a false picture at all because the color red is what we experience given the kind of visual system we have. — Marchesk

Our experience is observing the stop sign out there in the world. We describe it as being red because of the kind of visual system we have. If we had a different visual system, we would describe it differently.

No, I mean that our perception of room temperature is a creature dependent experience. Notice how one person can feel hot, another cold and third just right in the same room. This sort of perceptual relativity was noticed in ancient philosophy, leading to skepticism of external objects. If the honey tastes sweet for me and bitter for you, who is to say that sweetness belongs to the honey? Instead, I am sweetened or I am whitened was the preferred formulation of the Cyrenaics, similar to how we sometimes say I'm cold. — Marchesk

Right, it can be valid and useful to describe things in those ways. And it doesn't really matter whether you think of the honey as tasting sweet for you, or the honey as being sweet relative to you (consider the analogy with special relativity, where observational reports are reference-frame dependent). The actual experience is in the interaction between the subject and object. Whether or not your experience generalizes for others is an empirical question. If it doesn't, then it can be investigated further - is it due to genetics, or the environment, and so on. There is nowhere a need to posit qualia or sense data.

It's just a realization that naive realism is untenable, and we experience the world a certain way based on the kinds of bodies we have. — Marchesk

I'm arguing against both direct and indirect realism as generally conceived. What I'm arguing for is a relational view that, as you say, holds that we experience the world a certain way based on the kinds of bodies we have. What I'm also arguing is that language (whether ordinary or scientific) is grounded in our practical interactive experiences in the world, not in qualia or, on the other hand, in external/intrinsic/absolute properties.

it's pretty obvious when we discover that solid objects are mostly empty space and the the visible light we see is only a small part of the EM spectrum. It's clear we don't experience the world as it is, thus the distinction between appearance and reality. — Marchesk

There's no contradiction between an object being solid and being filled with mostly empty space. It's use doesn't imply that. But it's a good example of a false picture that people might hold. And some things are indeed invisible to the naked eye which we discovered by using, among other things, our eyes. It's no more or less a part of the world for that.

The distinction between how things appear and reality is fairly mundane. Most of the time a straight stick appears straight. But in some scenarios, such as when the stick is partly submerged in water, it appears bent. But we don't perceive "appearances" or qualia. They are ghostly objects that arise from invalid philosophical distinctions. -

Illusionism undermines EpistemologyWhich is also a false or misleading picture but for different reasons. T

— Andrew M

It's not, because some things we perceive are properties of objects and others are properties of our perception. — Marchesk

The false picture is, for example, that only one's perception of the stop sign is red (or some variant such as sense data or phenomena), and not that the stop sign is red.

But perception (and human experience) is the starting point for explanation whether ordinary or scientific. You don't get behind it or transcend it, you instead explain things in terms of it. Including, in principle, perception itself.

The room doesn't feel like anything objectively — Marchesk

I find that hard to parse. Do you mean we don't perceive the room? But we can feel the hardness of the walls when we touch them, or the coolness of the air. And that can be investigated scientifically.

It's also not clear what the "objectively" qualifier is adding if not just to say that such perceptions are beyond the province of scientific investigation. Which is just a reassertion of the hard problem.

Science is only possible because we can make these distinctions. — Marchesk

I'm only familiar with Locke's primary/secondary qualities distinction which is a philosophical distinction. I'm not aware that science makes any use of it, or why it would be useful. -

Illusionism undermines EpistemologySo you agree that it doesn't make sense to say that color, sound, etc. are illusions? — Marchesk

Color, sound, etc. are not illusions (i.e., stop signs are red). What is an illusion is the false picture of color, sound, etc., either as radically private or, its opposite, as definable independent of human experience.

Right, but the hard problem doesn't require ghosts in the body, only that we take the primary/secondary quality distinction seriously. — Marchesk

Which is also a false or misleading picture but for different reasons. The point is that, similar to optical illusions, such distinctions can affect how we perceive the world in hard-to-notice ways. -

Illusionism undermines EpistemologyThe goal is to dissolve the hard problem without just handwaving it away or giving into some form of dualism. But taken illusionism to its logical conclusion has serious ramifications for knowledge. When I perceive an apple, I'm not just aware of the apple's color or its taste, I'm also aware of it's shape and weight. Some qualities of human experience are the basis for science. But if color and taste are illusions, what reason would we have for supposing that shape and weight are not? After-all, we know about apples by experiencing them via our sensations of color, taste, etc.

I don't see how they can get around this. — Marchesk

With Dennett and Frankish, I'm skeptical of the hard problem, p-zombies, qualia, and radical privacy of experience.

A necessary part of dissolving the hard problem is to identify false or misleading pictures of consciousness. One such picture is the Cartesian ghost in the machine.

One illusion, then, is the ghost (along with its attendent qualia and radical privacy).

But a second (and opposite) illusion is that humans are machines.

What is needed is a different picture that doesn't implicitly assume the Cartesian model either in whole or in part. And that requires paying closer attention to the ordinary and specialized language that we use. Our practical experience in everyday life is what grounds our language and knowledge about the world (which, of course, includes language and knowledge about ourselves). -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceIndeed. Personally I have mostly encountered intellectually incurious realists, who believe they are right and everyone else is wrong, who ridicule and dismiss those who believe differently as cranks, adepts of pseudoscience, believers of supernatural bullshit, brain diseased, delusional, too stupid to see why they are wrong. — leo

Philosophy as a blood sport. However there are plenty of considered realists around. In QM foundations, for example, the interpretations are almost exclusively realist, though they take on very different forms (see the table on p2).

I think you are forgetting how familiar we all are with wishful thinking and its dangers. While it is sometimes geniuses who are thinking differently, perhaps that's the exception. — g0d

Yes, certainly there's that. But I also think differences are often due to underlying assumptions that are difficult to recognize and appreciate the consequences of. That's Wayfarer's claim of naturalism's blind spot (in support of the article) and my claim of dualism (in criticism of the article), for example. And, whatever anyone's motives are, there remains the issue of the merit of the arguments. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceBut Alice and some others already agreed on what was real, so this new person is wrong, he is delusional, he ought to accept what is real! And if he doesn't we'll lock him up and attempt to make him see the right way, 'cause we can't have him running around not seeing reality as it really is, y'know. — leo

I think the call for the pitchforks might have more to do with a certain kind of temperament than whether one subscribes to realism or not.

The more natural response for an intellectually curious realist would be to investigate why the new person thinks differently to the others given that they're all interacting in the same world. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceShe isn't modeling herself nor the people she encounters, she is modeling her experiences of herself and of the people she encounters. From her perspective she might say she is directly modeling people and herself, but from anyone else's perspective she is modeling her experiences of people and herself. — leo

If Alice thinks that she and the people she encounters are real (actually existing as a thing or occurring in fact; not imagined or supposed (OED)), then she will model them as being real. Similarly, if others accept that her reported observations and experiences are real (not as imagined or supposed), then they will also model those people as being real.

If you assume she is actually modeling other people, you quickly encounter the problem that these people exist and do not exist at the same time. They exist to Alice, but they do not exist to those who have never met them. Isn't it more coherent to say that she is modeling her experiences of them? — leo

That Carol hasn't met or heard about Bob doesn't imply he doesn't exist. It simply means that Carol has no internal representation for him. If Alice talks to Carol about Bob, then she can model him as well. That's simply knowledge-acquisition, not the creation of Bob for her.

It is impossible to derive from their models that photons of wavelength 460nm stimulating an eye will give rise to an experience of the color blue. It is impossible because they have neglected the human perspective. — leo

From the earlier scenario, "Alice ... finds the nearest seat, choosing to ignore the peeling blue paint that reveals the grey metal underneath." That is an account of Alice's experience in the world from her perspective. The ordinary use of the color term "blue" has its referent in things like the paint on the seat which is what Alice is observing and interacting with.

So I don't think you can say that the human perspective is being neglected above unless you're using "experience" in a private sense (how things seem to you) rather than in its usual public sense (practical contact with things).

What I think this demonstrates is a kind of 'presumptive naturalism', i.e. it arises from the very 'blind spot' at issue. And please don't take this as a pejorative because it's actually a very subtle and important point, and it's not by any means obvious. — Wayfarer

OK. But of course I think the blind spot is the assumption that the subject is not themselves an object, which is dualism. Of relevance to that, I'm curious where you stand on Wittgenstein's private language argument and its implication for private experience. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceThere is an implicit assumption in there, the assumption there is such a thing as facts and events existing independently of experience. But how did we arrive at these 'facts' and 'events' if not through our experiences? — leo

Yes that's exactly how we arrive at them. Per the OED definitions, a fact is "a thing that is known or proved to be true" and an event is "a thing that happens or takes place, especially one of importance". Which shows that facts and events have an epistemological and even normative aspect to them (in an age of "alternative" facts) as well as an ontological aspect.

Then if you start from these 'facts' and 'events' and attempt to model the modeler through them, you're not actually modeling the modeler, you're modeling your experience of the modeler. Most scientists don't realize that. — leo

Consider an ordinary, everyday scenario:

Alice steps gingerly through the train door and finds the nearest seat, choosing to ignore the peeling blue paint that reveals the grey metal underneath. Carefully placing her bag on her lap, she observes the other people around her. Several are tapping on their mobile phones, an elderly woman is napping opposite her, and a young couple at the far end of the train car are holding hands, chatting happily. Bob, a guy who works in the same building as her, catches her eye and says, "Good morning!". She smiles in acknowledgement while thinking, "I've had better". She winces as she becomes conscious of the pain in her ankle again. "Are you OK?", Bob asks, looking concerned.

So there are a number of experiences described there, some are Alice's, some are other people's, some are interactions between other people, or between her and others. All within the broad scenario of Alice catching a train to work.

Alice is modeling her experiences, which includes modeling the people she encounters (who, in turn, are doing the same, at least when they're not preoccupied) and she is even modeling herself (e.g., evaluating her morning, reflecting on her pains).

It's not a formal scientific model in the sense of a mathematical hypothesis that has been rigorously tested. But the basic elements are there. That is the human-oriented view with the experiences that ground scientific investigation and enable self-referential modeling. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceI'm happy to accept this idea if it is right, but I don't understand it. How could it ever be known that 'it doesn't have to', because even if there is a macro system that performs a measurement without a person, we can't know that the measurement has actually collapsed anything until we look at the macro system, at which point we become part of the system? No doubt I've misunderstood something and am happy to be corrected. — bert1

The apparatus can record the time of measurement along with the measurement. Decoherence happens extremely rapidly and pervasively so you'll be part of the system shortly after the measurement anyway even if you don't look. The difficult trick is actually to avoid decoherence which is why quantum computers are so difficult to construct. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceBut there is - which is the reflexive problem of 'the eye not being able to see itself'. We can't stand outside ourselves, or outside reason or thought, and see ourselves. We're always the subject of experience, and the subject is never an object of perception. This is the topic of the paper I mentioned by Michel Bitbol, It is never known but it is the knower - the title more or less serves as an abstract! — Wayfarer

That's the dualism that I pointed out earlier. Bitbol moves from the unproblematic example of an eye's blindspot to positing a world of appearances:

If we move anywhere even by thought or by imagination, we are still in our Umwelt; we are still thrown into the world of appearances. — Bitbol

science implicitly depends on the human perspective.

— Andrew M

You can say that now, but I bet if we had been having this conversation a couple of decades ago, it would have been fiercely contested. And really this whole debate is about making the implicit, explicit. — Wayfarer

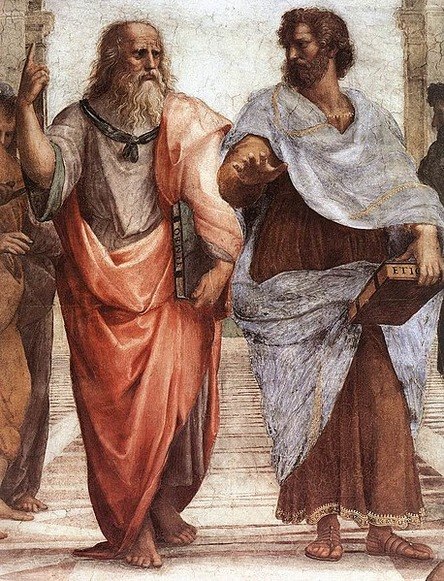

The history goes back further. This is just the difference between Platonic and Aristotelian realism. Plato advocated the God's eye view from nowhere, Aristotle the human-oriented viewpoint, as epitomized by the School of Athens fresco. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceThis all serves to set up the thesis that science neglects experience and the human perspective when, to the contrary, science has always been grounded in experience and observation.

— Andrew M

Science has always been grounded in observation, I admit. But "the human perspective"? Science explicitly rejects the human perspective, and aims to observe impartially, in an unbiased manner. No human perspective there. — Pattern-chaser

No, science implicitly depends on the human perspective. A referee in a football match, for example, can be impartial and unbiased but nonetheless has a human perspective. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceAnd if we acknowledge that we have just built a model of what we experience, then we can't use that model to say what we are made of and what we can or cannot do, because it is not a model of ourselves, it is a model of what we experience. — leo

Experience, which is "the practical contact with and observation of facts or events (OED)", is implicit in any scientific model. And that "practical contact" can itself be modeled scientifically.

In a general sense, there's the world, and there are separable systems within the world, from particles to human beings to galaxies, that we can seek to describe, explain and interact with. It takes a human (or similarly sentient being) to experience and model that world but there's nothing preventing the modeling of the modeler themselves.

As it happens, some of the interesting work and discussion in QM foundations at the moment is on Wigner's Friend scenarios which investigate the consequences of measuring the measurer.

As I see it, the puzzles of experience are front and center in science rather than neglected.

ALl due respect, you're not appreciating the point being made. As we have discussed philosophy of physics many times, think about this in relation to the Bohr-Einstein debates. Einstein was a convinced realist who believed exactly that physics should provide a grasp of sub-atomic phenomena 'as they are in themselves'. It was Heisenberg (so, the Copenhagen interpretation) who said that 'What we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning.” Einstein debated Henri Bergson in public forums about exactly the question of 'experiential time'. And the scientific view, by purportedly arriving at a quantitative understanding of the primary qualities of phenomena, does indeed aspire to what Thomas Nagel has described as 'the view from nowhere', which, I contend, amounts to the absolutisation of knowledge. This is why the discovery of uncertainty (which you solve with respect to the belief in 'many worlds') is such a big deal! — Wayfarer

Yes, these are all philosophical disputes about how to interpret the science. But one can take a realist position while rejecting characterizations such as "phenomena as they are in themselves" or "the view from nowhere".

I will sign off with the quotation of the concluding paragraph of the article:

To finally ‘see’ the Blind Spot is to wake up from a delusion of absolute knowledge. It’s also to embrace the hope that we can create a new scientific culture, in which we see ourselves both as an expression of nature and as a source of nature’s self-understanding. We need nothing less than a science nourished by this sensibility for humanity to flourish in the new millennium. — Wayfarer

So this seems like a radical call to ... do what we're already doing now!

Or am I missing something? -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceWell the irony is that one point of this approach is to heal the ‘Cartesian split’ which has given rise to this sense of ‘otherness’. The whole point of emphasizing ‘lived experience’ is to draw attention to the fact that science is a human enterprise, and that perspective is an ineliminable part of it. Whereas the whole gist of Galilean science has been that ‘what can be quantified’ is what most truly exists. — Wayfarer

Of course science is a human enterprise conducted from a human perspective. As I see it, the article itself presents a dualist framing. It repeatedly makes claims with dubious modifiers such as "reality as it is in itself", "a God's eye view of nature", "experiential time", "lived experience", "absolute knowledge" and so on. This all serves to set up the thesis that science neglects experience and the human perspective when, to the contrary, science has always been grounded in experience and observation. That's why it works. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived Experience"But these tests never give us nature as it is in itself, outside our ways of seeing and acting on things." - Aeon — Wayfarer

This seems to be the crux of it. By blindspot, they really mean that we can't see the road that we're driving on. Plato's Cave redux. That's a philosophical problem, not a scientific one. -

The case for determinismDoes that necessarily preclude what I stated in my post: that when you raise it to a higher level than the quantum level, things still start looking pretty deterministic? Take the laws of physics. If I throw a ball, the odds are pretty darned good that it's going to leave my hand and fly through the air. What are the odds that it won't leave my hand? 1 in a trillion? quadrillion? quintillion? Even if things are probabilistic and not certain at the quantum level, it seems that when you raise it up high enough, things still start to look pretty deterministic.

— MattS

Not in any long run, no. Small differences are amplified, not lost in the averages. Get familiar with chaos theory, or what is popularly known as the butterfly effect. — noAxioms

That's true for classical nonlinear systems. But quantum systems are linear and aren't so sensitive to initial conditions. From the SEP:

However, since Schrödinger’s equation is linear, quantum mechanics is a linear theory. This means that quantum states starting out initially close remain just as close (in Hilbert space norm) throughout their evolution. So in contrast to chaos in classical physics, there is no separation (exponential or otherwise) between quantum states under Schrödinger evolution. The best candidates for a necessary condition for chaos appear to be missing from the quantum domain. — SEP - Quantum Chaos

I think Mach-Zehnder interferometer experiments are a good example of this. Small differences in path lengths (and thus small differences to the phases of the arriving beams) make similarly small differences to the particle ratios measured at the detectors. -

What is logic? How is it that it is so useful?I notice most of the answers here have to do with logic's place as already useful. I find it interesting that an inquiry on the nature or origin of logic is almost considered impossible. What is the implication of that then? Well, you can just say, "It's foundatioanal", and "it is what it is", but how unphilosophical is that? Here we have a set of tools that we use in the world to create other tools, but we don't and refuse to look at it closely? — schopenhauer1

We notice that some arguments are truth-preserving, and we call those arguments logical. What further explanation of their nature or origin would be needed?

As an analogy, consider that the major encryption schemes that underlie internet transactions rely on prime factorization. But what is the nature and origin of prime numbers such that they are so special? Simply that primes are those natural numbers that have a specific characteristic that can be exploited for encryption (namely, that they are not divisible by smaller natural numbers). Similarly, logical arguments - those with the characteristic of preserving the truth of their premises - can be exploited for various things, such as building computers, solving problems and increasing knowledge.

Of course, those definitions don't exhaust what can be learned about prime numbers or logical arguments. But I think it shows that they can be understood as perfectly natural features of the world and not as intrinsically mysterious or other-worldly.

Is logic something that the universe provides? Are we divining/discovering logic? If so, is logic just how the universe operates? If so, is this different than the idea that we are divining/discovering math? Is that the same thing being that math is also an ordering/pattern principle? Is it more foundational or less foundational then math then as it might underride math (pace early Bertrand Russell).

If math is simply something that is nominal- we make it up to help make sense of the world, why can it be used so effectively in things like generating outputs from inputs? If put to use in a technological context, it is the basis for modern engineering, science, and technology. — schopenhauer1

The traditional view would be that thought, language and the world are isomorphic, that the world itself has a logical structure that can be discerned. The modern view would be that logic is about the form of sentences, not their content. Physics, understood as applied math, would seem to locate form in the world again as suggested by slogans such as information is physical. -

What is logic? How is it that it is so useful?I guess the main question is what is the nature of logic and how come it is that its nature is so useful to humans? — schopenhauer1

As an example, there are infinitely many possible syllogisms, 256 distinct forms, 24 of which are considered valid in traditional logic, and 15 in modern logic.

What a logician calls logic are just those forms or patterns that are deemed useful for certain purposes in the space of all possible forms and patterns. Understood this way, it's not mysterious that we distinguish patterns that help us achieve our purposes from those that don't. -

What Book Should I Read for a Good Argument in Favor of Naturalism?I understand that the word naturalism might be a bit vague. So let me just state a few of my beliefs that go against what I understand naturalism to be. I'm looking for something that will convince me I'm wrong on these points, or at least help me understand why so many philosophers disagree with me on them. — Dusty of Sky

I would recommend Gilbert Ryle's influential book The Concept of Mind. But note that it's not so much an argument for naturalism as a sustained argument against Cartesian dualism which, in some form or another, underlies a lot of the thinking on the points you raise below, including among naturalists. Also the book is not so much about nature as about language and how we talk about nature.

It may also be worth distinguishing between naturalism and materialism. A naturalist need not disagree with any of your listed beliefs below, though may frame them differently. My own responses follow.

1) I believe that consciousness neither consists of nor emerges from material phenomena

2) I believe that secondary qualities exist just fully as primary qualities

3) I believe that science paints a useful but extremely limited picture of reality

4) I believe that although science can give us lots of information about what matter does, it can't tell us why it ultimately does it (rather than something else), what it's ultimately made of, or where it ultimately came from.

5) I believe that certain (not all) universals exist in a way that is prior to their particular instances — Dusty of Sky

1) I agree, in the sense that ghosts neither consist of nor emerge from machines.

2) I agree, a red apple is red.

3) I agree, it's early days.

4) I agree, it's early days. Though I don't assume inherent limits on investigation, nor that investigation can only be conducted by people in lab coats.

5) I disagree. -

Is Physicalism Incompatible with Physics?I agree. And unless you think that there's an infinite regress of laws, you have to eventually ask why law A is in effect rather than law B or C. And regardless of what your answer is, I don't think you can attribute it to physical objects or their features. Laws are unchanging and exert control over all activity throughout the entire universe, whereas physical objects and their features change and they are limited to particular regions of space time. — Dusty of Sky

I attribute unchanging laws to the universe itself, one example being the law of non-contradiction. In its ontological sense, it's a form that is exhibited universally (i.e., in all objects).

I see no need to separate out form (laws/rules) from the universe. I think this comes down to a philosophical choice here - whether one prefers to conceptualize things in a unitary or dualist sense. -

Is Physicalism Incompatible with Physics?Physics is derived from the Greek 'study of nature', conventionally distinguished from metaphysics. So I would say, different in kind. Post Galilean science concentrates on what is quantifiable, first and foremost. The primary or measurable qualities or attributes of any subject are just those factors which can be precisely described in such terms. So the natural sciences likewise are conceived in mainly quantitative terms which is why physics is the paradigmatic science of modernity. But as the OP points out, in fact the ontological status equations, algorithms, and mathematical theorems, are themselves not something which can be located in the physical domain. So, yes, agree with you that metaphysics is in some fundamental way thinking about the nature of knowledge itself, about what it means to know. That is mostly shoved aside or ignored or taken for granted in a lot of analytical philosophy. — Wayfarer

OK. So as I see it, metaphysics is 'the study of the study of nature'. My observation here is that investigation begins with qualitative interactions with nature. That is, something can't be measured unless it can first be experienced, observed or otherwise interacted with. So those interactions become the material to be formalized. But that investigative process assumes observers, goals, tools and schemas.

However those observers, goals, tools and schemas are themselves part of the natural world that, in turn, can be investigated and therefore become material that can be formalized. So the qualitative and quantitative are present in both investigative processes, the second process being meta in the sense that it is reflective and self-aware. -

Is Physicalism Incompatible with Physics?If you mean, do I think there is in principle an explanation for scientific laws, the answer is: I don't think there is — Wayfarer

OK, thanks! However given what you go on to say, it seems you rule out a physical explanation for physical laws but not a philosophical (or theological) explanation.

I think that raises the question of what demarcates physics from metaphysics. Is it a difference in kind or a difference in focus? As I see it, philosophy goes meta by focusing natural investigation onto itself. That is, it is the investigation of investigation. -

Is Physicalism Incompatible with Physics?I see the issue as this - given scientific laws/regularities/order, then science can do an awful lot of work. But it doesn't explain those laws; it doesn't know why f=ma or e=mc2. Put another way, science reveals many things about the order of nature, but nothing much about the nature of the order ;-) And that is something that is often lost sight of. — Wayfarer

I think our philosophical premises are showing. :-) So if we can't discover the nature of the order by investigation of the natural world, then how can we discover it?

Do you think there is, at least in principle, an explanation? And if so where and how is it to be found? -

Is Physicalism Incompatible with Physics?Something seems very wrong to me about saying that everything in universe exhibits the same forms for no reason. And if there is a reason, I don't think the reason could be framed as simply a property of the objects which exhibit form. For instance, it seems to be a property of mass that it causes space-time to warp around it. But I don't think you can just take this fact at face value. Why does the universe exhibit these patterns? It's not logically necessary. Maybe it's physically necessary, but necessity, it seems to me, implies the existence of laws. Something can't just happen to be necessary. There must be something else that makes it necessary. — Dusty of Sky

If the universe is all there is, then there is nothing to reference outside of it. The reason why mass curves spacetime, if that's the right question to ask, is to be found by empirical investigation.

Assuming an external law wouldn't move us closer to an explanation. It would just raise the question of why there happens to be one particular law in effect rather than another. -

Is Physicalism Incompatible with Physics?So it appears you are asserting a Euthyphro-style dilemma. Either the universe obeys a law external to it or else there can be no law (in which case we should expect a disorderly universe). Would that be a fair description?

— Andrew M

I will tentatively accept your summary as a fair description, although I'm slightly worried that you have an argument in store that will make me regret doing so. — Dusty of Sky

Not a specific argument, just an observation. I think framing physical laws in that way implicitly assumes Platonic dualism. That is, Platonism assumes there is a material domain and a separate domain of forms. On that framing, subordinating form to matter would imply that physical laws are contingent and nominal rather than necessary and universal - and so not really laws.

But a different approach is to reject the Platonist framing. Instead there is a unitary universe that can be investigated and described in both experiential and logical terms. The universe exhibits form rather than obeying it or creating it as the horns of the dilemma suggest. -

Is Physicalism Incompatible with Physics?I think my reply to TogetherTurtle basically covers your argument. If the laws of physics are just descriptions of the way things happen to be organized, then they are not laws. And if the laws of physics aren't actually laws, then why does the universe obey them. It can't be random. What are the odds that every physical object, in the absence of laws, would always act as if it were governed by laws? Statistically infinitesimal, I would say. — Dusty of Sky

Physical laws are expressed as mathematical equations. So they are not merely descriptions of the past but are also predictions of the future. Scientists observe structure and patterns and hypothesize testable laws and explanations. That seems to work pretty well.

So it appears you are asserting a Euthyphro-style dilemma. Either the universe obeys a law external to it or else there can be no law (in which case we should expect a disorderly universe). Would that be a fair description? -

Is Physicalism Incompatible with Physics?Physicalism is the idea that nothing exists except for concrete objects in the material world. But physics is the study of the mathematic principles which determine the behavior of these material objects. And these abstract principles (e.g. F=G(m1m2)/r^2) surely don't exist in the material world. You can't locate them under a microscope. So acknowledging that the laws of physics exist seems to contradict the theory of physicalism. Thoughts? — Dusty of Sky

This reminds me of Gilbert Ryle's example of a foreigner visiting Oxford and remarking that he had seen the colleges and the libraries, but was wondering where the University was.

So I think one approach for a physicalist here is to say that the laws of physics aren't some additional thing that exists beyond what is observed. Instead their existence, if it is that, just is in the way that those observed things are organized.

(As it happens, Newton's Law is no longer considered to be one of those abstract principles since it's been superseded by GR.) -

Quantum experiment undermines the notion of objective realityAs I said, I don't think we have the principles required to precisely measure the various motions of objects in relation to the motions of light because we have not yet determined the relationship between objects and the medium in which the light waves exist. — Metaphysician Undercover

Then you don't have a model. Whereas special relativity is a self-consistent model that makes predictions that have been experimentally confirmed in numerous ways. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tests_of_special_relativity -

Quantum experiment undermines the notion of objective realityI don't understand the question. They see the thing which is emitting the light, as emitting light. — Metaphysician Undercover

Do you think light reaches the front and the back of the traincars simultaneously for both observers? If so, then what is the speed of the light? Is it c for the traincar observer, but c + v for the train-platform observer? Or is it c for both of them? Or something else? -

Quantum experiment undermines the notion of objective realityOK. So do you claim that the light emitted from the middle of the moving traincar towards the front is travelling at c + v (where v is the velocity of the traincar) from the train-platform observer's reference frame?

— Andrew M

I don't think that the movement of objects can be satisfactorily related to the movement of light, in the manner suggested by special relativity, because the relationship between the objects and the medium within which the light waves exist, has not been properly established. — Metaphysician Undercover

So apart from rejecting Lorentz invariance (in favor of Galilean invariance?), I'm not clear on what your model is. When the light is emitted from the middle of the traincar, what do you think the observers on the traincar and train platform see? -

Quantum experiment undermines the notion of objective realityAnother curiosity: what do you think about the problem of interfering branches in MWI (and maybe in RQM if no selection mechanism is accepted)? As 'I aM' (see here) noted it is true that due to the decoherence the interference term becomes very small. Yet, rigorously, it is not exactly 'zero'. Given the fact that decoherence occurs a lot of times, it seems possible that - sooner or later - interference will be observed. In other words, it seems that decoherence gives (multiple but) definite outcomes only 'for all practical purposes' (I remember to have read that decoherence is said to solve the measurement problem 'only for all practical purposes' but I am not sure that this the reason why it is said so...). — boundless

David Wallace has a good discussion of this in his paper Decoherence and Ontology, or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love FAPP.

As he puts it, decoherence gives us quasi-classical worlds (branches) but not actual classical worlds. Which means that decoherence can be treated as irreversible and the worlds as classical for all practical purposes. Nonetheless interference between branches continues to happen in accordance with quantum mechanics.

So the Wigner's friend thought experiment is a good example of this. For the friend, decoherence has occurred (i.e., the friend, measurement and lab have become entangled), but not for Wigner, who continues to detect interference and can, at least in principle, reverse the friend's measurement.

Whereas in the actual experiment of the OP, decoherence hasn't occurred since the photons involved haven't become entangled with their surrounding environment. Sean Carroll discusses this in his DailyNous essay on the experiment.

Right, that's the point. The assumption that the speed of light is invariant (which is essential to special relativity), is what produces these contradictions. — Metaphysician Undercover

OK. So do you claim that the light emitted from the middle of the moving traincar towards the front is travelling at c + v (where v is the velocity of the traincar) from the train-platform observer's reference frame?

Andrew M

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum