-

Is there a spiritual dimensionYou say that brain activity correlates with experience, well, but brain activity is not the experience lived. So, we cannot identified psychic activity with superior nerve activity. The superior nervous activity is the material substrate in interaction with the world that makes possible that world of images, ideas, etc. — armonie

I agree that brain activity is not the experience lived, but I do not see what your point is.

It is not a belief that you reach, it is a logical contradiction; or it rains or it doesn't rain. — armonie

You simply misunderstood what I said, “the spirit dissolves into the rest of the universe” precisely doesn’t mean that the spirit ceases to exist, it continues to exist in some way, like the material parts that composed the body keep on existing. -

Pursuit of happiness and being bornAll I have is the information I have now. As far as we know, there is nothing more than what we know through our experiences and senses. — schopenhauer1

Many people have had spiritual experiences, of existence beyond the material world, according to the information they have our existence doesn't stop with death. Maybe they're wrong, maybe they're right, why assume that they are necessarily wrong? If some sort of reincarnation is correct, convincing people to stop procreating won't prevent suffering.

My point was other forced acts are considered an aggression, but not this one. Outcomes would not matter, but if we are going to talk about outcomes, there is also collateral damage with this forced action (not just positive experiences). In any other realm of life, if someone forced upon another an action (especially one with mixed outcomes), it would be suspect at best, and deemed wrong at most. The principle of non-aggression was violated. — schopenhauer1

It's only a forced act if the person didn't want it. If a person doesn't feel that their existence was forced onto them, why would they see their birth as an act forced on them?

There is also collateral damage when antinatalists attempt to convince people that they are bad people for wanting to create a being through love, and help that being experience what makes life find life worth living. Most people are glad to be alive, it's mostly when they aren't that they ponder the point of life or think that they would have preferred not to be born.

If we can't agree on that then I suspect this would turn into a usual debate on antinatalism where neither side will be convinced. -

Discuss Philosophy with Professor Massimo PigliucciNice, I will definitely ask him some questions about the demarcation between science and pseudoscience, as I don’t see any such demarcation as objective nor as desirable, contrary to what he claims.

-

Being Good vs Being HappyWhat do you mean by "happy" here disconnected from the qualifiers "being" or "feeling"? — Dranu

What I meant to say is that being happy is the same as feeling happy, in case that was unclear, to me “being happy” refers to “feeling happy”. I don’t see happiness as something that can exist independently of the feeling of happiness.

Correct, which would be the difference between "being good (in itself)" and "being good for x". Both refer to "fulfilling some x". "Being good" fulfills its own nature and "being good for x" fulfills x. — Dranu

Would you say a pen can “be good” in itself, that it has its own nature that can be fulfilled? If someone uses a pen to write and someone else uses a pen to hurt and someone else uses a pen to point at something, what would be the nature of the pen?

A desire/purpose is what can be fulfilled, presumably a pen has neither in itself.

Yet if one is lacking good feelings, isn't there at least some quality of that person that is lacking goodness? Certainly feelings might not be as valuable as promoting other goodness in oneself, but its not nothing. Hence "feeling good" might not be "being good" even if its necessary condition for fully "being good." — Dranu

It depends what you mean by goodness. When we say “that person is a good man”, we refer to that person’s actions, not necessarily to what he feels. Some person could feel good about killing many people, but we wouldn’t say that person has goodness. “Feeling good” usually refers to pleasure, whereas “good feelings” usually refers to moral good, so the two are distinct, one can feel good about spreading suffering which isn’t considered a moral good.

Being happy can be seen as fulfilling one’s own profound desires. If you define being good as fulfilling one’s own profound desires (fulfilling one’s own nature) then by definition you see “being happy” as the same as “being good”. However that does not imply that being happy is necessarily being a morally good person. When you’re happy you’re good for yourself, but you’re not necessarily good for others. -

Pursuit of happiness and being bornIf no one was born in the first place, no one would need to collaborate. — schopenhauer1

It’s the same old “non-existence is better than existence”, which is your own personal belief. It would be quite ironical if when your body dies you don’t really die, that you keep existing in this universe in some way, and then you have to deal with convincing anti-natalists that they are doing nothing to make the world a better place.

Maybe you really did exist in some way before your birth, and you’ll keep existing in some way after your death.

However, I bet you certain aspects of non-aggression are followed in that culture, and I would simply use that. — schopenhauer1

To me, my birth was not an act of aggression. When I was born I didn’t cry, I looked around with curiosity. -

An Argument Against RealismWe can do that. But I should mention that I don't think we're free. The responsible, free agent seems to me like an important fiction, but a fiction nevertheless. As I see it, we're all entangled in the causal nexus. Even if we're not exactly predictable, I think we all have a sense of human nature. To have a nature is to be caught in necessity. — Eee

If you assume that our whole existence is a consequence of laws we have zero control over then you are led to that conclusion. However consider that so-called physical laws are only tested in situations where living beings are not present or have a negligible influence. It isn’t clear at all that our whole bodies or even our whole brains are subjected to these laws. It isn’t clear either that all our experiences reduce to brain states.

Our ideas appear in our 'minds' in languages that have evolved over centuries, though. — Eee

I said ideas, but not necessarily ideas expressed in a language, you might call it imagination or spiritual experiences, sometimes we experience things that are so different from anything else that we see it either as a connection to another dimension or plane of existence, or as us being able to freely create experiences that aren’t simply combinations of other experiences. -

Being Good vs Being HappyI would say being happy is the same as feeling happy, whereas being good is not the same as feeling good, and feeling good is not the same as feeling happy, so not the same as being happy.

For instance having sex usually feels good, yet often one doesn’t feel happy at the same time, so feeling good is not the same as feeling happy.

I don’t see what “being happy” would refer to besides “feeling happy”, so I will assume that “being happy” = “feeling happy”. Thus feeling good is not the same as being happy.

Now there remains to show the relationship between feeling good and being good. As you mentioned in your example with the pen, something being good can refer to it being useful in order to fulfill some purpose. But then that means that the same thing can be both good for someone and not good for someone else, depending on what is desired. A pen that works well won’t be much good to someone who desires to communicate with a blind person, for instance, while it will be good to someone who wants to write a letter. And even though the person writing the letter can see the pen as good, the person doesn’t necessarily feel good at the same time, that person could be quite sad for instance while writing the letter. And the pen can be good (for someone) without feeling anything itself. So being good and feeling good are decidedly not the same.

So by the above being good and being happy are not the same, they are quite distinct. You can be happy without being good, and you can be good without being happy.

Another way to see the difference between the two is that while being happy is related to the fulfillment of your own desires, being good is related to the fulfillment of desires that aren’t necessarily yours. Yet another difference is that you can fulfill your own desires without being happy, because you have more profound desires that you haven’t yet uncovered or that you have forgotten because you believed they cannot be fulfilled. Sometimes people say they have everything they need and yet they aren’t happy, they feel something is missing but they cannot quite put the finger on what that is. Whereas when a pen fulfills its purpose we say it’s a good pen, regardless of how we feel. -

Probability is an illusionSet aside the complexity of the issue for the moment and consider that given all initial values of a system the outcome pathway is fully determined. leo said that this isn't possible with 100% accuracy which I disagree to. — TheMadFool

I said it’s possible in very specific cases, most of the time it isn’t.

Take the simple example of a space probe. Using rockets in the right locations and fired for the correct durations we can and do predict that the probe lands right side up. — TheMadFool

It seems you missed the part where I said that the rockets are constantly controlled and stabilized during their flight, so as to remain on the desired trajectory. That control and stabilization is not predicted in advance, it dynamically adjusts to the conditions that the rocket encounters through a negative feedback mechanism.

This is a 100% prediction accuracy and if there are any inaccuracies they are due to unforseen cotingencies like wind or instrument malfunction. — TheMadFool

Without the dynamical control/stabilization the probe would never reach its destination. The unforeseen conditions that the rocket/probe encounters are precisely what makes the outcome unpredictable from the initial conditions alone. Which is why I said that the outcome is determined from the initial conditions alone only in simple cases where everything that happens is predictable, if you read my long post carefully you will find the answers to your questions.

I hope we can agree now that physical systems at the human scale are deterministic and that includes a fair 6-sided dice which I want to use for this thought experiment. — TheMadFool

Then consider the experiments where the outcome of each individual throw can actually be predicted, that is in simple situations with no wind except that caused by the dice, constant air density, constant temperature, smooth and hard surfaces. As I explained to you in real experiments the outcome usually won’t be exactly 1/6 for each side.

If the experiment is deterministic then there are a finite different number of ways to throw the dice, a finite number of initial conditions and outcomes, let’s call it N. If you measure all the outcomes, usually each side won’t appear exactly N/6 times. As I explained, if one side of the dice is slightly more sticky than the others, that side will show up quite more often. And even with the same stickiness, consider that a dice is not exactly symmetrical due to the dots or numbers printed or engraved on the surface, so in deterministic experiments the outcomes wouldn’t have exactly equal probability.

If instead you consider experiments where there is wind, or changing temperature, or irregular and soft surfaces, you can’t predict individual outcomes, and the various forces act together in such a complex way that they don’t prefer any particular side of the dice, even starting from the exact same initial conditions.

So for your thought experiment to make sense, consider that in deterministic systems where the outcome can actually be predicted in practice, starting from the same initial condition leads to the same outcome, and in such systems the dice does not land exactly as many times on each side.

1. We know that the system (person A and the dice) is deterministic because person B can predict every single outcome.

2. We know that the system (person A and the dice) is probabilistic because the experimental probability agrees with the theoretical probability which assumes the system is non-deterministic.

There is a contradiction is there not? — TheMadFool

No, because again, as I and others have explained, the theoretical probability does not assume the system is non-deterministic. In deterministic systems probability is not fundamental, if it confuses you use the term statistics instead.

You can come up with deterministic systems in which the dice will always land on the same side, or twice more often on some sides than on some the others. In some deterministic systems the dice lands about equally often on each side, in some other deterministic systems that’s not the case at all. Consider these latter systems and that will help you understand your error.

In deterministic systems the outcome is about 1/6 for each side only when the configuration of the system is such that it does not prefer any particular side. Some deterministic systems are like that. Some aren’t.

The problem is you assume in any deterministic system where each individual outcome can be predicted the dice will always land about equally often on each side. That’s wrong. Also in most situations where we throw a dice we can’t predict each individual outcome. Try to build a deterministic system in which you can predict each individual outcome, that will help you understand your error too. In your reasoning you assume that each individual outcome can be individually predicted, then consider real systems where that’s actually the case, where that’s actually done in practice, otherwise your thought experiment isn’t connected to reality.

In some deterministic systems the dice lands about equally often on each side because in such systems the symmetry of the dice doesn’t lead the system to prefer a particular side. How often an object lands on each side depends on the shape of the object, on its symmetries. You get symmetrical outcomes when you are dealing with a symmetrical object and when the system doesn’t break that symmetry. This doesn’t mean that the deterministic system is exhibiting non-deterministic behavior, there is no mystery here.

A coin is partially symmetrical, such that it lands most often heads or tails, but it can also rarely land on its edge. Yet you can construct a deterministic system in which it always or almost always lands on its edge (make a system in which the coin bounces or slides on inclined surfaces so that it ends up in a groove the same width as the edge of the coin). In this case the deterministic system prefers a particular symmetry of the object. In that system the coin wouldn’t land heads 50% of the time and tails 50% of the time. And just because you can say that in this system the coin lands on its edge about 100% of the time, using probability jargon, that doesn’t mean that the deterministic system exhibits non-deterministic behavior, just like when a coin lands heads or tails about 50% of the time that doesn’t mean that the deterministic system exhibits non-deterministic behavior, just like when a dice lands about 1/6 of the time on a given side that doesn’t mean that the deterministic system exhibits non-deterministic behavior, with the dice too the system can be configured so that some particular side/sides is/are preferred... -

Is there a spiritual dimensionThere is surely more than what we usually perceive. And the body is an appearance, not the underlying reality, brain activity is correlated to some extent to the experiences that are lived, but these experiences do not reduce to brain activity, for instance we would expect that brain activity would increase on psychedelics and yet studies have shown the opposite, even though they give more complex and vivid experiences.

So this leads me to the belief that either the spirit lives on after the death of the body, or the spirit dissolves into the rest of the universe. If we are more than the body, there is no reason that the ‘more’ would suddenly disappear into nothingness while the visible body remains. -

An Argument Against RealismI must confess that 'will' was a concept in Schopenhauer that I could never digest. I like many of his ideas, but 'will' struck me as too vague, and I'm still finding it vague here. — EeeCertainly human beings created laws, and certainly they had certain feelings tangled up in that. I can make sense of 'feelings' and 'actions.' — Eee

There are things that make us want to act, and making that desire an action can be seen as actualizing a will. So the will can be seen as a desire, which itself can be seen as a feeling, as an experience. If you want yes we can simply talk of experiences and actions. Actions create change.

So what is the action that makes things in the universe follow apparent regularities or laws? There is an action behind that, either an outside action, or an action stemming from all elementary particles that act together, in both cases there is an action permeating the whole universe.

I agree, and for this reason I expect the fact that we and the universe are here in the first place will remain mysterious. Or even unexplainable on principle, in that any explanatory principle would seem to have to be true for no reason. — Eee

Why then not see this universe as having been created and being maintained, with us having the freedom to act within a range of actions that the outside entity allows us to have?

Then you may ask who created that outside entity, maybe it was created by others and so on and so forth, or maybe action is what existence is. Sometimes we ask why there is something rather than nothing, but aren’t we able to create things out of nothing? Sometimes we have ideas that do not seem to come from anywhere, to be caused by anything, as if they were free creations. It seems quite ungraspable to us how something can come out of nothing, but maybe ‘nothing’ is simply an idea, a creation of the ‘something’ that exists beyond space and time, like what we imagine sometimes doesn’t seem bounded by space or time.

I agree about the problem of induction. But note that you suggest the will as an explanatory entity. This would be the law of the laws. Why should we expect to will to continue as it has? The will as intelligible entity (albeit vague) seems to be tangled up in time. It has a nature that can be leaned on as a source of hypotheses. — Eee

We shouldn’t necessarily expect it to continue as it has, but for now it does, because that’s what it chooses. We too are able to imagine worlds in which we give some entities the freedom to act within certain constraints. Maybe this whole universe is one great imagination or dream of that entity, who has given us the freedom to act within certain constraints, and who would then have the ability to send us into other universes or planes of existence.

Personally I don't believe it, but I do have other narratives, such as the value of mortality for forcing ourselves outside of our vanities, into a realization of how distributed and networked human virtue and knowledge are. If we were individually immortal, we might remain little monsters. Only together are we semi-immortal. The same great ideas and feelings move from vessel to fragile vessel. It's a hall of mirrors. Our own good and evil is reflected in millions of faces around us. My will is not at all single. For me we're all terribly multiple. — Eee

I wouldn’t say it’s the idea of mortality itself that forces us to not be little monsters, after all some people see mortality as implying fundamental pointlessness of everything and so that it doesn’t matter what we do, whether we spread happiness or suffering, whereas some other people want to spread happiness just for the sake of it, even if they believe they aren’t being tested and that there is no death.

I would rather say we ourselves ultimately choose how we act, whether we attempt to unite or separate, love or fear, understand or hate, within the constraints of the universe we have to work with.

To me this sounds like God, which is fine. But I need a voice from the sky or a burning bush. And even then I'd look for hidden technology. Even if certain things are possible, I'm also keenly aware that human beings are masters of fantasy. As I see it, we are haunted by visions. Our big brains are like fun houses. Perhaps we only face reality, when we do, in order to arrange things so that we can go back to sleep for as long and often as possible. Even this philosophy forum and philosophy itself is a bit like a dream in the context of the rest of my life. And yet I love to dream philosophy. — Eee

Personally I see the regularities in this universe as evidence of a creator, not necessarily a creator who is testing us but simply a creator who has given us free will to shape the world we want within the constraints he set. Fundamentally these constraints are very basic, as I said in another thread I believe eventually we will be able to unify physics in two fundamental forces, one that attracts and one that repels, both propagating at the same velocity, and in that universe we and others, not just other humans but all living beings who have the ability to act, decide how they use these forces to shape the world they want.

A potential objection to that is to say that if these are the only two forces then everything is determined and we have no freedom to act, but these would be the only two forces within what we see with our eyes, which isn’t the whole of existence, we ourselves aren’t defined solely by the body we see with our eyes, by our appearance, we are more than that, our ability to act isn’t limited to changing what we see, it also includes changing how we feel and how others feel, which we have barely begun to explore, and maybe in the end we will realize that we have also the ability to change the apparent laws of the universe, and that these laws weren’t constraints imposed onto us, but tools that we had to learn how to use.

And I can’t believe that arrangements of atoms who arose out of some random primordial soup through laws that were there for no reason would be able to imagine such things, and feel such beauty. -

The Universe is a fight between Good and EvilSo where’s the good and evil? Why mention good and evil? — Brett

Good is that which we usually associate with love, compassion, understanding, unity. Evil is that which we usually associate with fear, indifference, hate, separation.

Indeed they are not separate, they are just another name for the same thing, good is not a separate entity from the will that spreads it, and evil is not a separate entity from the will that spreads it.

I might have said in the past that Evil is an entity separate from us but if I did I was wrong, when we spread it we are it. Through our will we decide whether to spread good or evil, whether to work towards unity or separation. The fight between good and evil plays out within every one of us. -

An Argument Against RealismWhat is the evidence, though, of this will? Of course we have some intuitive notion, but don't we have an equally good intuitive notion of law? The idea of nature includes necessity. To me it seems that something like law is fundamental to any kind of talk of nature of essence. Time is quietly involved in all of our thinking. What can knowledge be if we don't expect what we have knowledge about to continue acting as it has acted? — Eee

Good questions, thanks for asking.

We also have an intuitive notion of law, but isn’t it the case that it is will that creates law? The laws that society follows were created by people through their will, and other people follow them.

Whereas the laws of Nature would be an instance of laws that spontaneously appear without a will involved, and we don’t have an intuitive notion of that.

There is no reason that the laws of Nature should continue being the same in the future as they have been in the past, we cannot know that they will, that’s the problem of induction. Maybe it is a will that is keeping them constant through time?

When I think of that it leads me to the idea that our existence within this universe might be a test, as some religions have proposed. Maybe there is a will that runs the laws of Nature in this universe, a will that has given us freedom to act within these laws, and watches what we are going to do with that freedom. -

The Universe is a fight between Good and EvilSo what is this ’evil’ that wants to separate? Can you name it? — BrettWhat are these forces? — Brett

I mentioned some of them in the post above, it’s important to read the whole of it.

Love, compassion, understanding, attractive forces are forces that work towards unity. Fear, indifference, hate, repulsive forces are forces that work towards separation.

In the post above I said moving towards unity makes us feel love and compassion, but love and compassion also move us towards unity, through love and compassion we spread love and compassion, which work towards unity, while on the other hand through fear and indifference we spread fear and indifference, which work towards separation.

I believe that eventually in physics we will come to a unified theory that will see two fundamental forces: one attractive and one repulsive. But physics only focuses on a part of existence, mostly on visual motion and not on feelings, so the attractive and repulsive forces it describes are only a part of the story, they aren’t the only attractive or repulsive forces. Love, compassion, understanding, ... are other attractive forces that work towards unity, while fear, indifference, hate, ... are other repulsive forces that work towards separation. -

The Universe is a fight between Good and Evil

Let’s forget about good and evil for a moment and just talk about unity and separation. I think you can agree that there are forces within us and within the universe that work to unite while other forces work to separate. And I think you can agree that unity is the opposite of separation (or division, disunity).

There are forces that attempt to unite ideas, beliefs, things, people, beings, while other forces attempt to separate them.

We find increased unity in beauty, in people helping each other, caring about one another, agreeing with each other, while we find increased separation in people fighting one another, seeing the other as inferior or superior, in disagreements.

Moving towards unity makes us feel love, happiness, compassion, while moving towards separation makes us feel fear, suffering, hate.

Physicists look for a theory of everything because they attempt to unite ideas, to reach a unified understanding, some force pushes them in that direction, you could see that force as their will, or their faith that such unity is possible.

However the world we observe cannot be described as total unity, a theory of everything in physics will not be able to see everything as unified, it is not possible to explain the existence of separation if fundamentally everything is unity. Put in another way, the world we see cannot be explained only in terms of attractive forces or repulsive forces, there has to be both: if there were only attractive forces all matter would shrink to zero volume, while if there were only repulsive forces everything would move towards an equilibrium where everything is separated and there would be nothing holding matter together. So a theory of everything in physics will necessarily have to see both attraction and repulsion as fundamental, it won’t be able to see everything as unified, attraction and repulsion cannot be unified, they are opposite.

But this does not imply that existence necessarily requires both attraction and repulsion. The existence of matter requires both, matter has a degree of separation, but it could be that spirits have no such separation. And that could be the spiritual feeling of universal love and unity and connectedness that some people have experienced, that complete unity is not to be found in the material world but it can exist beyond that world. While on the opposite side there could be universal fear and separation.

I made another thread yesterday that apparently has been deleted, it explored ideas in that direction and I think it made important observations, even if we could feel uneasy about some of them, but feeling uneasy about an idea doesn’t imply it is false. For instance killing leads to separation of a being from their loved ones, many people would agree that killing is evil, and we do that all the time in order to eat, or rather we let others do it for us so that we don’t have to face the bare reality of it. We attempt to cope with it in various ways, either by seeing other animals and plants as lesser beings (which is separating them from us), or by saying that it is okay to kill in order to eat (which implies a constant separation between beings competing with one another, and doesn’t consider that we could survive in this material world by eating much less). That’s something that most people refuse to look at.

They say that existence necessarily has suffering, necessarily requires competition and separation, because they assume that existence ends with the death of the material body. They don’t have faith in unity, they see death as the ultimate separation, and so they do all they can to avoid that imagined separation, by creating more separation. But it is fear in all its forms, including fear of separation, that causes separation. -

An Argument Against RealismThat makes sense. But then when the individual wants to know what the world's like independent of anyone perceiving it, questions about realism, epistemology and science come into play. And they might want to know this because they think there is a world that's more than just humans perceiving it. — Marchesk

Yes, but maybe the question "what the word really is independent of anyone perceiving it" is meaningless, maybe there has to be some being in order for there to be a world. I find it increasingly hard to conceive of a world devoid of beings from which beings arise. If there was a world that existed before beings and that behaved according to Laws, what made the things follow these Laws? The only evidence we have is that change occurs because of a will, when we will something we cause change to occur, we have no evidence that things change because they follow Laws independent of a will, that's an unsubstantiated postulate of modern science. -

An Argument Against RealismIt doesn't follow from the statement "We've been mistaken about some things" that we're been mistaken about everything. It does not follow from the statement "We do not see some things as they are" that we cannot see anything as it is. — creativesoul

That's not what I said either, I said we cannot all be seeing things as they are (otherwise there would be no disagreement), and I also said we cannot be mistaken about everything, for instance we cannot be mistaken about the fact that "not everything can be an illusion, there has to be something real". -

An Argument Against RealismYes, basically that's it, although the visual metaphor bothers me a little, because one might argue we're being fooled by thinking only in terms of vision, where illusions can occur. — Marchesk

Yes illusions can occur in all of perception, not just vision, by the word "see" I was referring to the whole of perception not just what we see when we open our eyes.

Terrapin Station (who is now banned, unfortunately, even though he was sometimes hard to discuss with I believe he has interesting things to say), considered that each individual perceives the world as it really is from their own point of view, from their own reference point, I believe that's true if properly interpreted, I wanted to discuss that more completely with him but I never got around to doing it.

That is, even if an individual doesn't perceive the world as it really is, what the individual perceives is influenced by some real things that influence his perception, so the individual perceives what the world really is like when these real influences are taken into account, but the thing is of course the individual doesn't perceive these real influences as long as they mess with his perception. -

An Argument Against RealismI think what could be agreed upon is that the world we see is an appearance, an image of something more fundamental than the image, and that this image depends on us.

Because if the world wasn't an appearance then we would always see things as they are, yet different people see things differently, believe differently, and so we cannot all be seeing things as they are. And there has to be something more fundamental because otherwise everything would be illusion and that's not possible, there has to be something real in order for there to be an illusion. -

Probability is an illusionOk. Let's suppose that a normal-sized dice is a "chaotic system" and is actually probabilistic. Just blow-up the dice - increase its size to that of a room or house even. Such a dice, despite its size, would continue to behave in a probabilistic manner despite our ability to predict the outcomes accurately. After all you do accept that rocket trajectories can be predicted and therefore controlled. — TheMadFool

If we somehow launch the house-sized dice fast enough it isn’t clear that we could predict individual outcomes accurately, because again an extremely tiny change in how the dice is thrown or in the wind or in exactly where and at what angle it bounces would change the outcome. While if we launch it so slowly that the dice doesn’t rotate, we would predict the outcome but then it wouldn’t be probabilistic anymore.

Rocket trajectories aren’t predicted with 100% accuracy, in the atmosphere their trajectories are constantly corrected and stabilized in order to stay on a given course, and in space they are also corrected every now and then, because they encounter accelerations (due to various phenomena: wind, dust, radiation pressure, ...) that aren’t predicted beforehand with 100% accuracy.

However it is possible to have systems where overall the outcomes are overall probabilistic even though we can predict each outcome individually. Consider a simple system where you throw the dice so slowly and at such low height that it doesn’t rotate while in the air and it doesn’t rotate after bouncing. Then you can always predict what the outcome will be, but in order for the outcomes to be probabilistic you have to change the initial conditions probabilistically (namely the initial orientation of the dice). So if 1/6 of the time you start with 1 up, 1/6 of the time 2 up ... and so on, you know that the dice will land 1/6 of the time with 1 up, 1/6 of the time with 2 up and so on.

It is also possible to have systems where you don’t control the initial conditions (contrary to the above example), where you can predict each individual outcome and where the outcomes are still probabilistic overall. For instance let’s say you pick 1000 people randomly (from various places without looking at them) and each of them writes their age on a piece of paper, so you have 1000 pieces of paper with some number on them. Now say you pick 10 pieces randomly, you add the 10 numbers together and you divide by 10, that gives you the average of these 10 numbers, let’s call it N1. You put the 10 pieces back with all the other and again you pick 10 pieces randomly, you carry out the same process and you get another number, N2, and so on and so forth, you do that many times. Each time you pick 10 pieces, the outcome number can be predicted (you just have to take the sum and divide by 10), however it can be shown mathematically that the numbers N1, N2, N3, ... follow a probabilistic distribution, a so-called normal (or Gaussian) distribution, that’s to say that most N values will be gathered in a tight range, and the further away from that range the less and less values there are, and you can compute how probable it is for a random N value to fall into such and such range. So before you pick 10 pieces of paper again, you know how likely it is that their average will fall into such and such range.

Going back to the example of the dice, is it possible to not control the initial conditions, to be able to predict each individual outcome and yet the overall outcomes are probabilistic? It is possible in some specific cases:

What has an influence on the dice is the initial conditions (the orientation of the dice when it is thrown and the velocity and angle at which it is thrown), and the forces acting on the dice during its motion: air friction that depends on the initial conditions, on air density, on wind; bouncing force provided by the surface on which the dice bounces that depends on the initial conditions, on the local hardness/elasticity of the surface, on the shape of the surface as well as that of the dice; and surface friction when the dice is rolling on the surface, which also depends on initial conditions and on the surface itself as well as that of the dice

If the air density, air wind, and the properties of the surfaces didn’t change, then that means that if you launched the dice several times with the same initial conditions, you would always get the same outcome. So if these properties didn’t change, in order for the outcomes to be overall probabilistic, the initial conditions would have to be probabilistic (so you would have to always throw the dice differently). Since the forces acting on the motion of the dice depend on the initial conditions in a complex enough way, a tiny change in initial conditions will be enough to usually change the outcome. And since the dice can only land in 6 possible ways, we can expect to get each side about 1/6 of the time.

Otherwise, if you always launched the dice with the same initial conditions, in order for the outcomes to be probabilistic the air density/wind and/or the properties of the surfaces would have to change between each throw, but then it would be impractical to accurately measure these evolving conditions and so it would be impractical to predict individual outcomes.

So in practice, if you conduct the experiment in a closed system where the air density is constant, where there is no wind besides that generated by the dice, and where the surfaces are hard and regular enough (both the surface of the dice and the surface on which the dice bounces), then it is possible to predict individual outcomes and to have overall probabilistic outcomes only if you always change the way you throw the dice (otherwise if you throw it in the exact same way you are guaranteed to get the same outcome and then the overall outcomes won’t be probabilistic).

And now to finally answer your questions, notice that in both this last example and in the example with the numbers on pieces of paper, any individual outcome is deterministic, but the way these outcomes are distributed is probabilistic. In the last example of the dice, in all the ways that the dice can be launched, in about 1/6 of the case the dice lands on a given face, because the dice can only land in 6 different ways, and the forces acting on the dice are complex enough that they don’t lead to one side being more likely than the other, whereas if the forces were much simpler (like in the example where the dice never rotates during its motion) then one side would be preferred. In the example of the pieces of paper, it can be shown mathematically that the outcomes are distributed in a probabilistic way, following a Gaussian probability distribution: that’s called the “central limit theorem”.

In deterministic systems probability is not fundamental in the sense that if we can’t predict an individual outcome it’s only because of incomplete knowledge. As to your second question, the deterministic system does not exhibit fundamental probabilistic behavior, a more correct way to phrase it is that it exhibits statistics, due to the configuration of the system itself. In the dice example it is possible to configure the system in a way that some outcome is preferred, for instance always starting with the same initial conditions. Or we could start with different initial conditions but make one side of the dice more sticky than the others so that the dice will land more often on the sticky side.

In deterministic systems probabilities are not fundamental, rather we compute statistics that depend on the configuration of the system, which can be interpreted as a characteristic or a property of the system. The probabilities in deterministic systems refer to incomplete knowledge, so in the example of the dice where the outcome can be predicted, we would say the dice has a given probability of landing on a given side when we have incomplete knowledge of the initial conditions or of how the system reacts to these initial conditions.

Say there are N different possible configurations of initial conditions, and we know the system always reacts the same to a given initial condition (because in that particular system when we precisely measured the initial condition and we kept it the same we always got the same outcome), and we know that in about N/6 configurations the dice lands on a given side (because we have thrown the dice a great number of times in that system with different initial conditions and that’s what we have noticed), but this time when we throw the dice we don’t measure the initial condition (the initial velocity/angle/orientation of the dice), then we say that the dice has about 1/6 probability of landing on a given side, but that’s only because we don’t know in which deterministic configuration we are once the dice is thrown, because we haven’t carried out the necessary measurements that would provide us with that knowledge.

And depending on the system the number doesn’t have to be exactly N/6 for each side, in most deterministic systems it wouldn’t be exactly N/6, depending on the dice and on how the system reacts to it.

That turned out longer than I expected, hope that helps. -

Probability is an illusionPhysics/mechanics???!!! We've put men on the moon. Surely a humble dice is within its reach. — TheMadFool

It doesn’t take 100% accuracy to put men on the moon. Also modeling gravitation in space is much easier than modeling all frictions on a dice thrown in the air and bouncing on a surface: the dice will bounce differently depending on the hardness of the surface at the precise point where it bounces, and a tiny change in the angle at which the dice bounces will totally change how it bounces and its subsequent motion, so it’s a chaotic system, a tiny difference in initial conditions will change the final state of the dice and in most cases we can’t measure all relevant variables with sufficient accuracy. Also, the guys going to the moon could control their trajectory to some extent during the flight, whereas we don’t have little guys controlling and stabilizing the dice while it flies and bounces :wink: -

The Universe is a fight between Good and EvilAugustine was Manichean before converting to Christianity. And a point that is worth considering is Augustine's post-conversion teaching of 'evil as the privation of the good'. This is the principle that evil has no intrinsic or ultimate reality, that it merely comprises the absence of the good, which is real. So, as illness is the absence of health, and shadow the absence of light, then evil is the privation of the good. So it doesn't see the same kind of stark opposition, even though it can recognise evil as evil. — Wayfarer

It is interesting to read the story of how Augustine converted to Christianity:

a disappointing meeting with the Manichaean Bishop, Faustus of Mileve, a key exponent of Manichaean theology, started Augustine's scepticism of Manichaeanism. In Rome, he reportedly turned away from Manichaeanism, embracing the scepticism of the New Academy movement. At Milan, his mother's religiosity, Augustine's own studies in Neoplatonism, and his friend Simplicianus all urged him towards Christianity. Not coincidentally, this was shortly after the Roman emperor Theodosius I had issued a decree of death for all Manichaean monks in 382 and shortly before he declared Christianity to be the only legitimate religion for the Roman Empire in 391.

Is it more coherent to see the issuance of a decree of death for thousands of people as the absence of good or as the existence of evil? The issuance of such a decree is a willful act, that leads to suffering and death, it is hard to see it as a mere absence of good.

It is interesting also to see how Manichaeans were persecuted and slaughtered globally, even by Buddhists:

Manichaeism was repressed by the Sasanian Empire. In 291, persecution arose in the Persian empire with the murder of the apostle Sisin by Bahram II, and the slaughter of many Manichaeans. In 296, the Roman emperor Diocletian decreed all the Manichaean leaders to be burnt alive along with the Manichaean scriptures and many Manichaeans in Europe and North Africa were killed. This policy of persecution was also followed by his successors. Theodosius I issued a decree of death for all Manichaean monks in 382 AD. The religion was vigorously attacked and persecuted by both the Christian Church and the Roman state. Due to the heavy persecution upon its followers in the Roman Empire, the religion almost disappeared from western Europe in the 5th century and from the eastern portion of the empire in the sixth century.

In 732, Emperor Xuanzong of Tang banned any Chinese from converting to the religion, saying it was a heretic religion that was confusing people by claiming to be Buddhism. In 843, Emperor Wuzong of Tang gave the order to kill all Manichaean clerics as part of his Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution, and over half died. They were made to look like Buddhists by the authorities, their heads were shaved, they were made to dress like Buddhist monks and then killed.

Many Manichaeans took part in rebellions against the Song dynasty. They were quelled by Song China and were suppressed and persecuted by all successive governments before the Mongol Yuan dynasty. In 1370, the religion was banned through an edict of the Ming dynasty, whose Hongwu Emperor had a personal dislike for the religion.

Manicheans also suffered persecution for some time under the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad. In 780, the third Abbasid Caliph, al-Mahdi, started a campaign of inquisition against those who were "dualist heretics" or "Manichaeans" called the zindīq. He appointed a "master of the heretics" (Arabic: الزنادقة صاحب ṣāhib al-zanādiqa), an official whose task was to pursue and investigate suspected dualists, who were then examined by the Caliph. Those found guilty who refused to abjure their beliefs were executed. This persecution continued under his successor, Caliph al-Hadi, and continued for some time during reign of Harun al-Rashid, who finally abolished it and ended it.

So many people who claim that evil doesn’t really exist, that there is only good (or its absence) and then go on to commit these atrocities. Calling evil the “absence of good” doesn’t make it any less evil, on the contrary it is a way to pretend it doesn’t exist, so that it can spread more easily. -

The Problem of Evil and It's Personal ImplicationsWhether there can be love without attachment is a valid question, to which a Buddhist would answer in the affirmative. To explain how and why is perhaps better left to actual Buddhist teachers and not me.

To the question of how to deal with destructive forces, I would tend towards a "turn the other cheek" approach. The assumption is that all men are Good in essence, but are corrupted by their material existence. By giving the right example one may cause them to see the error of their ways. An "eye for an eye" or "fight fire with fire" approach are fundamentally flawed as solutions, though.

However, understanding attachment and the cause of suffering doesn't mean one may never act to preserve something, like in the act of self-defense. One would simply have to accept the suffering that may come along with such an act.

Lastly, I would disagree that loss or separation is the root cause of suffering, since without attachment there is no sense of loss or separation. — Tzeentch

Yes I agree that one can love without attachment, however what I ultimately meant is that if we aren’t attached to love and to life, destructive forces could destroy life and love, and then ultimately there wouldn’t be love anymore.

I agree that the approaches “an eye for an eye” and “fight fire with fire” are fundamentally flawed, but the approach “turn the other cheek” is only valid if as you say the assumption that all men are Good in essence is true, or to put it in another way if Good is necessarily more powerful than destructive forces, or if turning the other cheek necessarily leads destructive forces to eventually stop being destructive. But is that really true?

Rather I would say there are plenty of examples of people who have turned the other cheek and who were simply destroyed, and then we say that these people were too weak for this world. Turning the other cheek is not enough to stop destructive forces, Good needs to be strong as well, not wanting to hurt but not always turning the other cheek, Good needs to stand its ground and say no to destructive forces, in order for Good to spread.

And so to me the “being detached” and the “turning the other cheek” approaches miss an important part of the picture. Loving while being detached so as to never suffer makes love vulnerable to destructive forces. Loving while turning the other cheek also makes love vulnerable to destructive forces. In fact I would say in both cases one attempts to be detached from suffering, while not working on protecting love. Love doesn’t just need to be given, it also needs to be protected in order to not be destroyed.

And then while being completely detached allows to avoid suffering, that doesn’t imply that attachment is the root cause of suffering, because if there were no destructive forces then one wouldn’t need to be detached in order to avoid suffering. Rather, these destructive forces are the root cause of suffering, because if they weren’t there then there would be no loss or separation. Destructive forces aren’t only found within men, they are also found in Nature, but there are also forces in Nature that work to protect life. What if then the struggle between Good and destructive forces that plays out among men and among life also plays out in Nature? What if Nature is not moved by eternal Laws but by Wills that are in constant struggle, with one Will attempting to protect and spread life and another opposite Will attempting to destroy life? Cannot we make sense of everything by seeing things that way? -

The Universe is a fight between Good and EvilSo here Leo bases good and evil on happiness and suffering. He's actually a hedonist. — Banno

Hedonism is about pleasure and pain. Pleasure is not the same as happiness, pain is not the same as suffering, they are unmistakable, if you’re conflating them then maybe you haven’t really felt happiness and suffering. Happiness is not a high degree of pleasure, an extremely intense sexual orgasm is not necessarily accompanied with happiness. Suffering is not a high degree of pain, an extremely intense pain is not necessarily accompanied with suffering.

So I’ll return your comment to you:

That's what counts as quality philosophical thinking now? — Banno

Also, you seem to have hate for the ideas I am presenting, to the point that you want to censor them:

This thread ought be removed. — Banno

The desire for censorship stems from hate and/or fear, it is the desire to prevent people from expressing ideas or prevent people from hearing them, to hinder communication between people, it is the desire to separate. Maybe with some introspection you would come to realize that the distinction between good and evil I am referring to is more profound than it currently appears to you. -

Rigged Economy or Statistical Inevitability?It really isn't obvious that this model accurately represents what goes on in reality, we can come up with plenty of different mathematical models starting from different premises that lead to centralization of wealth, so the fact that one particular model predicts centralization of wealth does not imply that the premises at the basis of this model are the root cause of wealth centralization.

For one it is based on the yard sale model, in which wealth is never created, it is only exchanged, can we really see that as an accurate representation of reality? For instance it basically means that you are always paid what your work is worth (plus or minus a tiny amount), so if you force 1000 people to build a luxurious palace for you and you give them $1 a day in compensation for their work, supposedly that palace would be worth about the total amount you gave to the workers, which is obviously wrong. Say they build it in 1000 days, that palace would surely be worth much more than $1 million.

This model would have luck or randomness as the main force driving economic inequality, while ignoring the forces that actively act to create and maintain that inequality for their own self-interests. The other article you linked gives a much more plausible account of what actually goes on:

The political system, coupled with high initial inequality, gave the moneyed enough political influence to change laws to benefit themselves, further exacerbating inequality

Are we really to believe that the rich do not exploit the poor, always pay them what their work is worth, do not act to profit at the expense of others and are only innocently exchanging wealth in a big yard sale?

We have the technology to produce basic necessities much more efficiently than in the past, why do so many people struggle so much to get them still? It's not the result of an unfortunate law of mathematics written into the fabric of the universe, it's by design. The vast majority are made to struggle, so that they earn just enough to pay rent and food and a tiny surplus to keep them entertained and prevent them from revolting. The more they struggle without revolting, the more the rich can profit off their work and enjoy the results. The surplus of wealth produced by the workers doesn't go back into the hands of the workers, it goes and stay in the hands of those they work for, so that the workers keep struggling and producing a surplus that they never get to enjoy. -

The futility of insisting on exactnessThe underlying difficulty is we don't know what other minds experience, we attempt to guess it based on how they behave, how they look, how they sound, ...

Some people seem to be able to read people better than others, is it simply that they are very attentive to the clues that the other person gives off, or that in some way they are able to directly experience what the other experiences?

In uttering words we attempt to convey what we experience, to give rise to that experience in others. With some people sometimes it seems that a few words do the job, or even no word and just looking at each other is enough, while with some other people it seems that even after repeated clarification the essence of the experience doesn't get through to the other side.

We can try to be as clear as we can, but then we can't be clearer than that. Sometimes no amount of words or explanations can convey what a picture can convey or what hugging someone can convey. Sometimes people are in a state where they aren't ready to listen or to understand something because they feel in a specific way or because what they are told is in conflict with some deeply held belief.

Words are one tool to communicate, not the only one, so in the situations where that tool doesn't seem to work it seems indeed futile to insist on using it with exactness and hoping that if only we use it precisely enough it will start working.

One example I like to use is that of the dictionary. Even if we all used the exact same dictionary, with all the exact same definitions for each word, we would still have zero guarantee that we would understand one another, because there is a missing link between the words and what experiences the words refer to. A dictionary relates words with one another, not with actual experiences, feelings, perceptions.

Without that link it doesn't help to strive for more exactness by using the same definition of a word, and then the same definitions of the words that make up the definition of the word and so on and so forth, because eventually the original word is defined in terms of itself, circularly. What breaks the circularity is the link between words and experiences, which more precise definitions do not provide.

But we don't have an objective link, each of us has their own personal link, and words alone do not help to clarify these links, rather we need to interact with people in other ways in order to uncover what they experience and to communicate what we experience more precisely. Maybe exactness could be reached, but not through words. -

Prohibition of drugs. Criminals love to see it. Why do we make their day?This is also a good read: https://harpers.org/archive/2016/04/legalize-it-all/

Americans have been criminalizing psychoactive substances since San Francisco’s anti-opium law of 1875, but it was Ehrlichman’s boss, Richard Nixon, who declared the first “war on drugs” and set the country on the wildly punitive and counterproductive path it still pursues.

I started to ask Ehrlichman a series of earnest, wonky questions that he impatiently waved away. “You want to know what this was really all about?” he asked with the bluntness of a man who, after public disgrace and a stretch in federal prison, had little left to protect. “The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

Nixon’s invention of the war on drugs as a political tool was cynical, but every president since — Democrat and Republican alike — has found it equally useful for one reason or another.

The desire for altered states of consciousness creates a market, and in suppressing that market we have created a class of genuine bad guys — pushers, gangbangers, smugglers, killers. Addiction is a hideous condition, but it’s rare. Most of what we hate and fear about drugs — the violence, the overdoses, the criminality — derives from prohibition, not drugs.

“if you fight a war for forty years and don’t win, you have to sit down and think about other things to do that might be more effective”

What exactly is our drug problem? It isn’t simply drug use. Lots of Americans drink, but relatively few become alcoholics. It’s hard to imagine people enjoying a little heroin now and then, or a hit of methamphetamine, without going off the deep end, but they do it all the time. The government’s own data, from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, shatters the myth of “instantly addictive” drugs.

In other words, our real drug problem — debilitating addiction — is relatively small. Addiction is a chronic illness during which relapses or flare-ups can occur, as with diabetes, gout, and high blood pressure. And drug dependence can be as hard on friends and family as it is on the afflicted. But dealing with addiction shouldn’t require spending $40 billion a year on enforcement, incarcerating half a million, and quashing the civil liberties of everybody, whether drug user or not. -

Prohibition of drugs. Criminals love to see it. Why do we make their day?And one of the reasons there is a war on drugs (on some drugs really) is that there is another cartel that governs us and that makes a lot of money by only allowing certain drugs and controlling the distribution of said drugs. Another reason is that it is a tool for social control. The war on drugs does not help prevent harm, it creates it.

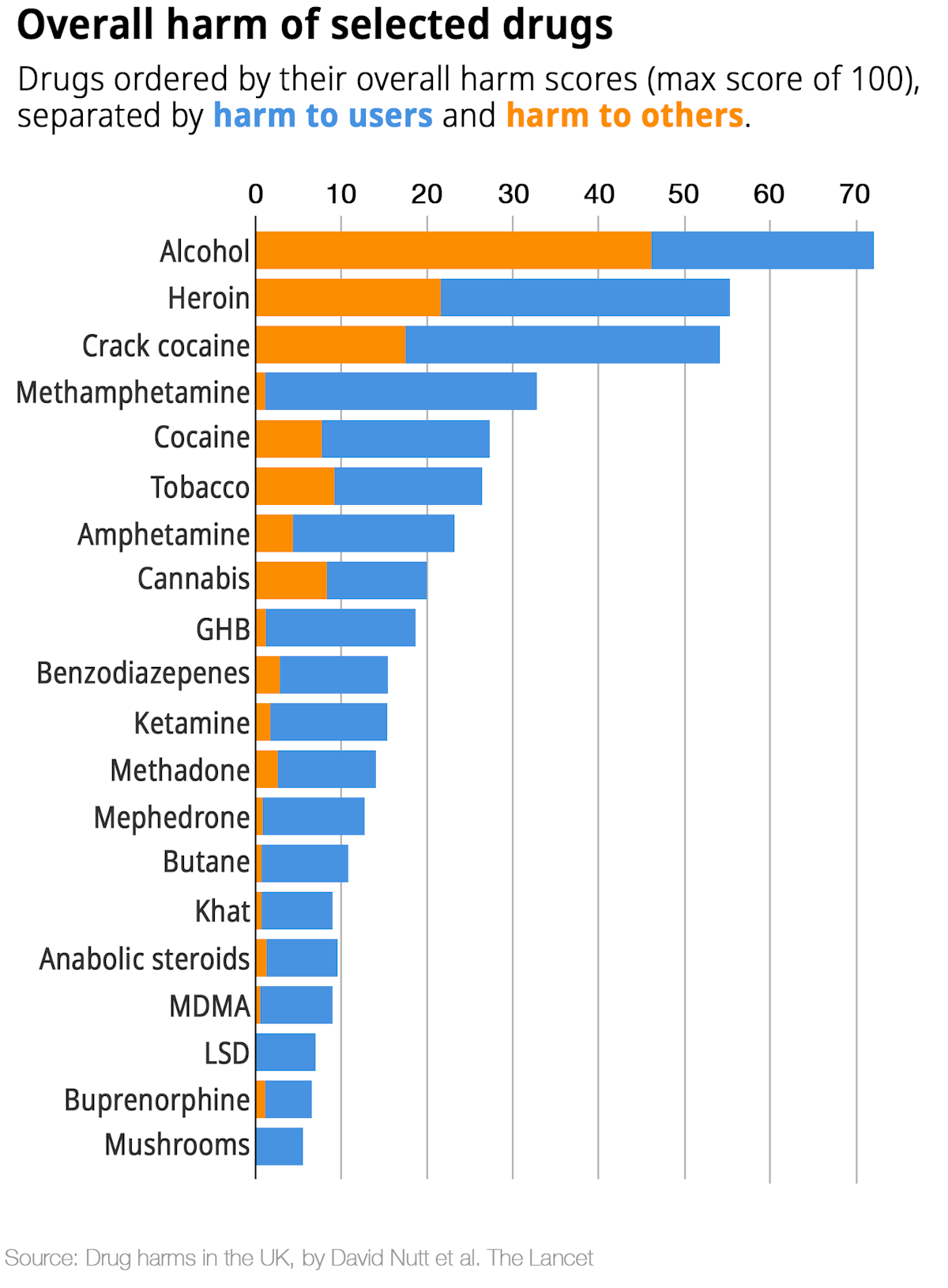

There is a study that ranked various drugs in terms of the harms that they produce in the individual and the harms that they cause to others, based on 16 criteria: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(10)61462-6/fulltext

These are the results (the greater the score, the greater the harm):

Alcohol comes out first, yet it is legal. The idea that the ultimate goal of the war on drugs is to prevent harm is a myth.

So how do you push those who govern the people to do something for the people when they don't have their best interest in mind? Well those who govern us are not all-powerful and they aren't invincible either, so while they won't do something if it's in your best interest, they will do it if it's in their best interest. If more and more people become aware of these issues, and more and more people push for change, those in power will feel that their position of power is threatened, and then they will act to retain it by answering the people's demands to appease them. -

The Problem of Evil and It's Personal ImplicationsAttachment to material things, including people and indeed one's own life, is the source of most if not all of man's suffering. Since all that is material is fleeting, loss of these things is unavoidable, and attachment to these things is irrational. By attaching ourselves to things which one will unavoidably lose, one is setting themselves up to suffer. — Tzeentch

That’s the one thing I disagree with in Buddhism. While I agree with the idea that attachment to desire leads to suffering, how can there be love without attachment to life? If some powerful force wants to cause suffering and destroy all life, are we supposed to watch it happen and be content that we are not suffering because we are not attached to anything? And then beauty and love and happiness will be gone, is it worth it to give up all that just to avoid suffering?

And then, isn’t it that the root cause of suffering is not attachment to desire, but loss itself, separation? Becoming detached is a way to cope with loss, but what if loss is not a fatality but something caused by an evil that really exists beyond one’s mind? Then seeing loss as an unavoidable fact of existence would be blinding ourselves to this evil and be left with two options: suffer, or be detached from love and from life. -

The Problem of Evil and It's Personal ImplicationsNot necessarily. Some methods of ‘stopping evil’ contribute greatly to suffering. War, for instance, does not ‘emit a good’. — Possibility

One could argue that war contributes to evil instead of stopping it. Fighting suffering with suffering does not stop suffering, fighting fear with fear does not stop fear, ..., love does. Good spreads as evil shrinks and vice versa. -

Free will seems to imply that this is not the only worldIf you see a model M, then you can argue that they satisfy a theory T. Fine, but now you also see that there are facts in the model that cannot possibly be predicted by such T. That creates the situation that there are statements that are true in model M but not provable in theory T. According to model theory, this means that there must be at least one other model M' which also satisfies theory T but in which these facts are false. That is why these facts are true in M but not provable in T. — alcontali

Do you agree that saying there are two universes that satisfy theory T does not necessarily imply that the two universes actually exist? That is my point.

For instance there could be a finite universe and an infinite universe that both satisfy a theory T, that doesn’t imply that both universes actually exist, it could be there is only one of them.

Saying that something exists in the realm of mathematics does not imply that it is actualized in reality. I understand your argument, if we know that our universe satisfies a theory T and we have free will then we can conceptualize other universes that satisfy this theory T, but there is a missing step between existing as a concept and existing in reality. Unless you assume that everything that we can think exists beyond our thoughts.

We cannot create these other worlds. — alcontali

Then what you call free will is not really free, it is constrained. And if you define free will as the ability to do things that cannot be predicted, in principle it could be possible to do things that can’t be predicted without having control over them, in which case it would decidedly not be a free will in the way that it is usually considered.

But regardless of the question of free will, I generally think that proving that several concepts (models) are consistent with another concept (a theory) does not imply that these concepts exist as more than concepts. Unless again you assume that everything that can be thought exists beyond thoughts. -

Free will seems to imply that this is not the only worldWell, in normal English, yes. In model theory, no. In model theory, a theory T is a set of rules, while a model M is a set of values, i.e. an "interpretation", that satisfy these rules.

The universe itself is not a set of rules. It is a set of values that satisfy the rules of the ToE. — alcontali

Okay, but then it seems you assume that this set of rules existed prior to the universe which would be an instantiation of these rules, whereas we have no evidence of these rules existing before, rather we attempt to infer a ToE from the universe we do observe.

There are many universes consistent with an incomplete theory, but even if somehow we found a ToE, and even if somehow we knew that the rules of the ToE existed before the universe, it still wouldn't prove that there are other universes, because it seems to me the incompleteness of the theory only implies that many possible universes are consistent with the theory, not that these universes exist as more than possibilities.

However if we have free will it seems to directly imply that we can create other worlds. As to why we seemingly can't, it could be that our will is constrained by some other will, in which case our will is not completely free, or it could be that we willed to give ourselves the appearance that it isn't free even though it is, and then in principle it could be possible to get out of that state and apply our free will and we just haven't found out how yet.

Also it seems a will cannot be completely free as long as there are other wills, unless there is only one will and we are all a part of it and the one will gave us a limited will, which is the view of a version of idealism in which the whole universe and ourselves exist within a cosmic consciousness.

Personally I hold the view that wills are not constrained by rules or laws but by other wills, or more specifically as I mentioned in another thread that there are two wills constraining one another, the will of Good that seeks to unite and the will of Evil that seeks to separate, that we are part Good part Evil and so our resulting will is constrained by the conflict between the two, and that in order to have free will we would have to make the will of Evil disappear, and then we would all be united as one, with a free will that would seek to do no evil, for having a free will is having the ability to do anything one wants, rather than actually doing anything, even if one could in principle. -

reflexivityI assume this is the paper https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5731606/

Every ontology that a social scientist adopts has an auto-referential import for the epistemic status of the impersonal knowing subject. More simply put, general ideas about the ordinary knowledgeability of social agents impinge back upon the one who offers these ideas – for that person is a socio-cultural agent as well. This means that, in the case of the philosophy of the human sciences, there is a need for metaphysical reflection which moves further than reflecting on an ontological scheme – that is, a need for reflection on the fact that the sociologist, as a knowing subject, is existentially related to her or his partial or greater object

One implication – and a useful example – of this problematic is that relativist theories, which deny or suspend the possibility of (fallible) reflection, face this auto-referential problem. As Lawson nicely puts it:

The denial of the possibility of knowledge may seem a wild and anarchistic claim, but it is at first sight intelligible and logically unremarkable. But matters cannot be left there. This denial involves a reflexive problem, which appears trivial but which cannot be eradicated with the ease that one might expect: if it is not possible to provide knowledge, then how are we to regard the text of the philosopher that asserts this very point? Since it is evidently paradoxical to claim to know that knowledge is not possible, philosophers who have wished to make this type of claim have usually engaged in the more wide-ranging attempt to alter the nature of their text in order to avoid a self-contradictory stance. (H. Lawson, 1985: 14)

Following the same line of thought, deterministic social ontologies, which deprive social individuals of their creative agency, are similarly problematic. For ‘just as the sceptic or relativist seems, in asserting his thesis, to be making the sort of knowledge claim his thesis excludes, so also the determinist is said to be doing something in asserting determinism which this very thesis excludes’ (Boyle, 1987: 193). And in attacking sociological relativism and social determinism, I intend to propose an epistemic criterion in response to this auto-referential problem of epistemic reflexivity.

The problem is described in this quote, basically it is the problem of how to take into account the influence of the theorizer on what he/she theorizes: the scientist sees the world through his/her eyes, experiences, beliefs, and doesn't see the world independently of that, so what is the domain of validity of his/her conclusions?

Regarding minimalist and maximalist reflexivity, the following passage offers some clarification (emphasis mine):

Accordingly, for Lynch (2000), general philosophical and epistemological problems like the theory-ladenness of observation, the under-determination of theory choice by evidence, or the omnipresent problem of how descriptions correspond to their objects, are classic and important, but bear no special, either positive or negative, epistemic implications for specific local scientific engagement. For this reason, scientists should ignore this general and abstract philosophical problematic and focus on the specific issues arising from their particular research programs. For reflexivity cannot offer anything more than what every effort to attack objective truths offers, so there is no particular benefit to being radically reflexive unless something worthwhile emerges from it (Lynch, 2000: 42). Consequently, it is pointless to require that, every time a scientist makes a statement, he or she should list all the presuppositions and contingent conditions which influenced his or her research, thus pre-emptively replying to every possible imaginary critique regarding the uncertainty connected with these conditions. After all, ‘a project that deconstructs objective claims should be no more or less problematic, in principle, than the claims it seeks to deconstruct’ (ibid.).

Hence, for Lynch, the limit to the number of meta-theoretical ‘confessions’ necessary in order for one to be reflexive is social, and there is no single way of being reflexive.

Within this framework, Lynch suggests ‘an alternative, ethnomethodological conception of reflexivity that does not privilege a theoretical or methodological standpoint by contrasting it to an unreflexive counterpart’ (Lynch, 2000: 26), and which underlines the ordinary and uninteresting character of the constitutive reflexivity of accounts, that is, of the uninterested reflexive uses of ordinary language and common-sense knowledge. This constitutes a minimalistic attitude towards self-reflection, the ordinariness of which implies that its epistemic virtues are not certain and determinate. It is in this sense that Pollner complains that ‘from Lynch’s perspective, the analyst is deprived of any analytic vantage point. It is the move from referential to endogenous reflexivity’ (Pollner, 2012: 17).

Yet, in this article, I would like to argue against this minimal ethnomethodological form of self-reflection and thus claim that there are various forms and degrees of self-reflection, which are always relative to each specific society, group, class, etc. Indeed, Archer (2007: 49) is right that it is unintelligible to conceive of a society with such a level of socio-cultural cohesion that agents do not need to reflect on the content of action. And, indeed, this is somehow an ordinary socio-cultural phenomenon. However, Lynch (2000) does not leave theoretical space for such a variety of levels and degrees of self-reflection. Thus, what Lynch is implicitly against is the presupposition of the self-reflective knowing subject (reflecting on her or his own ontological presuppositions), which constitutes a sub-class of the general presupposition of the general, omnipresent and ordinary notion of self-reflective subjectivity.

Again, both ordinary self-reflection and its radical maximalistic version of the knowing subject should be distinguished from epistemic reflexivity, which is an auto-referential property of social ontological schemes.

Basically the author distinguishes between various degrees of self-reflection (not to be confused with epistemic reflexivity).

Maximalist self-reflection would be to self-reflect on all presuppositions and contingent conditions which possibly influenced your conclusions, which would be extremely impractical (you would have to consider the possible influence of your mood, the time of day, the weather, your memories, your past experiences, all your beliefs, ..., on your conclusions).

Whereas minimalist self-reflection is the opposite end of the spectrum, where one would not particularly attempt to self-reflect beyond what one is naturally inclined to do, so for instance you would carry out research which would naturally involve some self-reflection, but you would not reflect about the importance or extent of that self-reflection and its influence on your results.

The author argues that there are various degrees of self-reflection in between, for instance you could reflect on the influence on your results of the society/group/class you belong to. Maybe another scientist belonging to a different society/group/class would reach different conclusions from you while carrying out similar research, because both of you wouldn't have self-reflected on the influence of your society/group/class in shaping your presuppositions and beliefs and thus your conclusions. Whereas if that other scientist and you would both have self-reflected on the influence of your society/group/class on your thought process and implicit beliefs, you two might have reached the same conclusions.

In a nutshell maximalist self-reflection is impractical, and minimalist self-reflection is imprecise (leads to conclusions that have a limited and unknown domain of validity). The more you self-reflect on the possible variables that influence your conclusions, the more you know the limits of their domain of validity and the greater that domain of validity, but you can't reach the state of self-reflection on all possible variables which would yield conclusions of certain universal validity, unless you somehow had access to universal truths.

The author gives an account of theory-building, but that account is based on presuppositions as well, his conclusions about self-reflection depend on his own presuppositions so they don't necessarily have to be seen as universal truths. He makes a model of model-making, but one could make a model of modeling model-making, and so on and so forth in an infinite regress. In order to reach universal truth one has to see it, otherwise it seems one can't reach it through reason and logic. But partial knowledge is still useful to reach some goals, for instance regarding the various degrees of self-reflection, we've seen that two people who disagree with each other can end up agreeing by carrying out more profound self-reflection, thus increased self-reflection can be seen as a way for people to unite. I realize this is going further than the question of your thread but I feel it is interesting and important to point out. Cheers -

Free will seems to imply that this is not the only worldSay that there is a Theory of Everything (ToE) and that this world is its model. — alcontali

Shouldn't it be that a ToE is a model of the world rather than the other way around?

I would say if we have free will then we have the freedom to create alternative worlds, which doesn't necessarily imply that there are alternative worlds, but they can be created. -

Is religion the ultimate conspiracy theory?A reconstruction of Keeley’s argument that we discussed in my Philosophy of Religion class is the following: — ModernPAS

From what you outlined his argument boils down to "if everything can be doubted then conspiracy theories can be doubted too, and what can be doubted should be rejected so conspiracy theories should be rejected", but those who believe in a conspiracy do not necessarily believe that everything can be doubted, and what can be doubted shouldn't necessarily be rejected, so his argument is self-defeating.

An analogous argument can be made for the claim that religious belief is self-defeating: — ModernPAS