-

Theories without evidence. How do we deal with them?Yes, and you can make up a million other bullshit scenarios and call it philosophy too; but they'll all be bullshit and they'll all be made-up, and of each of them you could say: "but it's all about that...".

-

Theories without evidence. How do we deal with them?If I am in my apartment then I am not a BIV. — PossibleAaran

What kind of disjunction is this? What motivates it? Nothing. It might as well read: "if I am in my apartment than I am not a cloud; so this has everything to do with clouds". It's child's talk. -

Theories without evidence. How do we deal with them?I have good reason to believe that I am in my apartment. — PossibleAaran

I'm sure you do. Of course, this has nothing to do with being or not being a BIV and everything to do with having a proper grasp of the English language. -

Theories without evidence. How do we deal with them?What reason is there to believe that I am in my apartment? — PossibleAaran

Well this can be answered quite straightforwardly: none. Maybe you're in your apartment, maybe you're in a library, maybe you don't even live in an apartment, maybe a million other things, but, from your posts so far in this thread at least, there is literally no reason - apart from you now intimating that you do - to believe that you are in your apartment. Speculation here is contained by available and public evidence, and does not begin out of thin air, without grounds. That's the difference.

--

Alternatively, if you're asking the question of yourself (while being in your apartment), then, pace Wittgenstein, you don't understand how the English language works. -

Theories without evidence. How do we deal with them?I said the question can be dismissed at the level of its form: the fact that it asks for reasons why something isn't the case. Your reply, which quibbles over the content of the questions, is irrelevant. One can make up any bullshit one likes and then ask why it isn't the case, and then pretend like it's just a matter of being an impartial, rational inquirer. But if you don't have grounds to pose a thesis, then you don't have grounds to have anyone take it seriously.

Yeah how do we know they don't do this?! What reason do we have to think the lizard people don't do that?? -

Perpetual representative realism—A proposal of where knowledge could stem fromHow strange. A kind of epistemic occasionalism, or occasionalist anamnesis.

In any case, the so-called 'higher consciousness' is simply a god-of-the-gaps style invocation. It explains nothing and itself demands explanation. -

Theories without evidence. How do we deal with them?Is there any reason to think that we are not brains in vats...? — PossibleAaran

As a general rule any unmotivated question of the form 'is there any reason to think that such-and-such is not the case' can be readily dismissed out of hand. It is the conspiracy theorist's question: "is there any reason to think the Queen is not a lizard?; "is there any reason to think we are not ruled by aliens?"; these are not questions to be taken seriously. They are questions to be laughed at and ridiculed.

If BIV was a simplifying explanation of the way things are, it would be compelling. In fact, it is radically complexifying. — hypericin

:up:

As if the BIV thesis itself did not demand a radical profusion of things to be explained. Anyone who thinks it might function in an explanatory capacity in any sense fails to understand the English use of the term 'to explain'. -

Ontology: Possession and ExpressionAgamben's actually piqued my interest a little in Buddhism, insofar as he's been referencing - although sparingly - a couple of Brahmic texts in some of his recent work. One of his recent books was even titled karman in reference to, well, you should know. I'm not sure I'll have time anytime soon to look into it very deeply, but it does seem like there is some cross-over with the ideas at stake here.

:sweat: -

Ontology: Possession and ExpressionDo you think this metaphysics of expression admits of different degrees of expression? — fdrake

Yes, but I think exactly what this means would need to be carefully specified. It's not that the star luminesces more or less brightly, but that the star itself qua luminescent has more or less a degree of being. Again, the danger to watch out for is in ascribing degress of expression to this or that property of a subject, and not the thing itself. Exactly what this means is, I think, something open to different readings: Spinoza thought about such degrees in terms of conatus, for example (the 'striving for a thing in its persistence', roughly), while Nietzsche will think of it in terms of differential wills-to-power (which everything 'is'). I use these examples because I think it helps show that the two different approaches to ontology are just that - approaches, which can be cashed out in different ways (just as 'posessive ontology' has undergone many permutations thoughout its history).

Deleuze and Agamben are two others I would fit in this lineage of expressive ontology as well, although they too differ radically in the detail of how that is worked out. -

Self-explanatory factsIf entailment cannot be achieved by negation of totality — Posty McPostface

I'm still not sure what this means. -

Self-explanatory factsCan you set out your reasoning? I don't want to have to guess at it, especially because I'm not super familiar with that whole debate.

-

Ontology: Possession and ExpressionThe idea I believe is that the modes express substance and that substance is nothing other than its expression in the modes.

-

Self-explanatory factsI know you said not to attack P2, but there's a way to do it which I think might be really interesting, which is to question whether or not S can really constitute a totality. I'm borrowing here from Meillassoux's 'argument from power sets' in his After Finitude, but the idea is that for every set of facts S, we can always generate another, additional fact by taking the power set of S (the set of all subsets of S), which will always yield a set S' with more elements than our original set S: that is, it will always contain one additional fact not contained in our original set of facts S. This procedure can be repeated to generate sets of ever increasing cardinality (set size) so that from S' you can generate S", and from S'', S''' and so on ad infinitum.

What this allows you to do is question the hard and fast distinction in (P3) between S and something other than S, insofar S cannot be understood to be a self-contained totality in the first place: with S alone, one can generate something other than S. This line of attack doesn't so much deny that S can or cannot be self-explanatory, so much as put into question what it might even mean for something to be self-explanatory (or, alternatively, be 'explained by something else'). It frames the whole exercise as a kind of paralogism in Kant's sense, an attempt to deal with a whole that cannot in fact be made whole to begin with.

I think what this opens up is the question of what even constitutes a fact, and necessitates a look into the means by which facts are individuated, but that's probably a bit much to deal with here. -

Theories without evidence. How do we deal with them?To the degree that a theory is meant to do explanatory work, to provide good, substantiated, reasons why the explanandum behaves or exhibits the behaviours or features it does (and not otherwise), in no conceivable universe does the BIV thought-experiment constitute a ‘theory'. @LuckilyDefinitive is also right that a theory without evidence is simply called a hypothesis, and that to confuse the two is simply bad intellectual hygiene.

-

Ontology: Possession and ExpressionAnother appeal to me of the turn to expression is that it accords nicely with Deleuze’s insistence that the priority afforded to ‘what is…?’ questions in philosophy have been massively detrimental to the whole enterprise:

“What is…? This noble question is supposed to concern the essence, and is opposed to vulgar questions which only refer to the example or the accident. Thus you do not ask who is beautiful, but what is the Beautiful. Not where and when there is justice, but what is the Just. Not how “two” is obtained, but what is the dyad. Not how much, but what… And yet this privilege of the What is…? is itself revealed to be confused and dubious, even in Platonism and the Platonic tradition.

For the question What is? in the end only animates the so-called aporetic dialogues. Is it possible that the question of essence is that of contradiction, and that it itself throws us into inextricable contradictions? As soon as the Platonic dialectic becomes a serious and positive thing, we see it take other forms: who? in the Politics, how much? in the Philebus, where and when in the Sophist, in what case in the Parmenides”. (Deleuze, The Method of Dramatisation). -

Predication and knowledgeIt's not clear from what you've adduced here whether being is created in language, or (merely) expressed through and by language. We could recast the question as, Is there being absent language? — tim wood

Not quite any of these; to put it more simply, for Aristotle, the 'characteristics' of Being are the same as the 'characteristics' of language. Aristotle's ontology is not an 'expression' of language nor 'dependent' on it or whatever; it's simply that it shares the same structure (so just as one speaks of subject and predicate, for example, in Aristotle Being is articulated by essence and accident, the one reflecting the other); it's a matter of an 'isomorphism' between Being and language, if it can be put that way. Or in the words of the linguist Emile Benveniste, who first drew attention to this:

"Aristotle thus posits the totality of predications that may be made about a being, and he aims to define the logical status of each one of them. [However], these distinctions are primarily categories of language and that, in fact, Aristotle, reasoning in the absolute, is simply identifying certain fundamental categories of the language in which he thought. ... He thought he was defining the attributes of objects but he was really setting up linguistic entities; it is the language which, thanks to its own categories, makes them to be recognized and specified. No matter how much validity Aristotle's categories have as categories of thought, they turn out to be transposed from categories of language.

It is what one can say which delimits and organizes what one can think [in Aristotle]. Language provides the fundamental configuration of the properties of things as recognized by the mind. This table of predications informs us above all about the class structure of a particular language. It follows that what Aristotle gave us as a table of general and permanent conditions is only a conceptual projection of a given linguistic state." (Benveniste, Problems in General Linguistics).

Again, the import of this is that of course you find predication every time you look for it: it's because the tool you're using for your search is language.

And for me it's not a matter of being surprised that the fridge light is on, but rather that I've come to question just what it means that the light is on; and wonder that it is, apparently, the only light there is. — tim wood

It is not the only light it is. There are other ways to approach ontology that are not simply confined to Aristotle's equivocations between language and Being. Agamben, who I cited previously, for example, advocates for what he refers to as a 'modal ontology' where (following Spinoza), Being is expressed modally, in terms of its manner or 'way' of Being, and not, as per the Aristotelian model, in terms of the distinction between substance and accidence (and hence subject and predicate: an ontology of 'possession' as distinct from an ontology of 'expression'). Deleuze, elsewhere, suggests speaking of Being according to the grammatical category of the infinitive, such that we do not say 'the tree is green' but rather 'the tree greens' (this is not a great way to communicate of course, but that's the point - the needs of communication are idiosyncratic and hardly generalizable, so we should not expect that the world is simply structured like our language).

I mention these two examples obviously only in their most bare-bones form, but the point is that ontology - and in its wake knowledge - is not exhausted by the subject-predicate articulation, and we should be incredibly suspicious about any approach to knowledge which simply sees in it what it is put there to begin with. Not only is it circular, but it is highly inattentive to other ways of looking at things which are out there. -

On Life and ComplainingEvidently quite a bit, considering the frequency with which it is done. You should read - if you can get your hands on it - Aaron Schuster's "Critique of Pure Complaint" (in his Deleuze and Psychoanalysis).

-

On Life and ComplainingIf we didn't care we wouldn't complain. These things are complimentary, not disjunctive. The apathetic on the other hand - those who don't even care enough to complain - they are the true uncaring.

-

Small Requests ThreadI realize we didn't reply to this, but we had a small discussion over in Mt. Mod, and we decided against it. It was a case of letting those small question threads bloom into their own discussions if possible, and also, the questions category is an appropriate one for them. The price might be some clutter, but we think it's an OK one to pay. Cheers for the suggestion though.

-

Predication and knowledgeWhile it's true that one often 'finds predication at the bottom of things', one has to wonder if this is due to a confusion of the tool for the object: that is, language. Wayfarer is right to point out that the primacy of the subject-predicate distinction is primarily Aristotelian in inspiration, and it should also be noted that Aristotle himself modeled his understanding of Being precisely on the structure of language:

"Aristotle treats here [in the Categories] of things, of beings, insofar as they are signified by language, and of language insofar as it refers to things. His ontology presupposes the fact that, as he never stops repeating, being is said (to on legetai...), is always already in language. The ambiguity between logic and ontology is so consubstantial to the treatise that, in the history of Western philosophy, the categories appear both as classes of predication and as classes of being.

.... The structure of subjectivation/presupposition remains the same in both cases: the articulation worked by language always pre-sup-poses a relation of predication (general/particular) or of inherence (substance/accident) with respect to a subject, an existent that lies-under-and-at-the base [hypokeimenon, as Wayfarer again pointed out -SX]. Legein, “to say,” means in Greek “to gather and articulate beings by means of words”: onto-logy." (Agamben, The Use of Bodies).

Agamben's own take is that this modelling of Being upon language - and, implicitly, knowledge upon language - has massively overdetermined the trajectory of Western philosophy, and that what is needed is an entirely new approach to all of it. But regardless of that, the point is simply that it is unsurprising that, in the necessary recourse to language to expresses knowledge, we 'find predication': it is not unlike opening the fridge door and being surprised to find that each time, the fridge light is on. -

The (In)felicitousI think performative utterances as described by Austin are parts of an act, in combination with non-verbal conduct and recognized customs, in some cases the law, or rules. — Ciceronianus the White

This seems to me a verbal dispute rather than a substantial one, but the point is well taken. In fact, the 'insufficiency' of the speech-act unto itself, the fact that it relies on a whole nexus of institutions, powers, histories, and habits which enable (or disable) it, is what makes it so interesting to me. Specifically my interest is in the way felicity provides an alternative criterion for linguistic 'success' than truth: a criterion of 'efficacy' rather than adequation, a material rather than cognitive criterion of success.

Moreover, in/felicity seems to me to be far more broadly applicable to language than truth: truth has always struck me as a 'regional' language-game, important in its own right and in the proper circumstances, but largely uninteresting outside of those contexts. Questions of felicity though, seem to me to saturate basically all our utterances. -

Can Members Change Their Screen Name?Members can change their screen name, but they have to request it, and can't do it on the fly. If you think there's a particular member running more than one screen name, let a mod know via PM and we'll look into it. It generally isn't allowed.

-

The (In)felicitousFelicity and infelicity would serve as an interesting topic for epistemology. Instead of analysing how propositions connect to truths through justifications, we could analyse what makes certain speech acts good or bad in accordance with their function.

It would be a curious epistemology though - a kind of para-epistemology, in the sense that this kind of analysis would not be a search for 'adequation' (between 'knowledge and thing') but a search for conditions of possibility (of felicity): thus a transcendental epistemology. The really cool thing about such a seach is that such a transcendental would not be a fixed one, but rather, a variable one: for a while there, two men would have been unable to pronounce a felicitous affirmation of "I do" at the altar; and now, in some places, this has changed. Which means that the question of felicity is directly connected to the questions of politics: of power, authority, recognition, and rebellion - Who holds the power? Who confers the authority? What institutions uphold it? What history undergirds it? (where 'it' is that which enables the felicitious/efficacious enunciation of a speech-act).

Transcendental analysis of this kind would thus not have to merely be 'reflective' of the real: it could even, in some cases, be productive of it; a particular kind of discourse could be self-authorizing ("we are married!"), or at least bring the new into circulation by the stubborn insistence of its own self-affirmation (a bit like Badiou's fidelity to the Event, which, perhaps ironically, is what he says inaugurates Truth itself). This halo of thoughts is why I think that issues around felicity are (Badiou's 'truth' aside), far more interesting than questions of truth. -

The Collective Philosophy of 'Relative Poverty'Reflect for a moment what it would take to get you - and not only you but your entire town - to leave everything you have and move - not to another town, in a country that might still at least be familiar to you at the level of history and tradition - but to another country entirely. Consider still not bringing anything with you but the clothes on your back, perhaps a small backpack, and a few rolls of toilet paper (because getting by with a little food and water is possible if still miserable; but imagine now being unable to clean yourself after a light soiling in a foreign bathroom or outdoor pit: I mean really think about what might have to go through your head that planning for this might become a real consideration in your life).

Now consider a shitstick of a commentator, observing your flight, and not only questioning your status as a refugee ('refugee', in scare quotes), but, because you don't look like you're in a state of 'extreme depravity' (one imagines the bar for this is when you're matted, bloody, crying, and half your family is dead), your plight is really just a 'philosophical crisis', and that it's in fact caused by a bunch of 'group-think' or whathaveyou.

Nevermind that 'the destitute' are always entitled to whatever dignities are in fact their own - quite literally their own possessions (like, say, some decent clothing); nevermind that the majority of poor people don't really look like the caricatures on TV, and in fact often dress quite decently; nevermind that problems like obesity are a frequent symptom of the working class (lacking the money to afford a healthy, well-balanced diet, and an environment that would encourage well-rounded eating habits); nevermind too, the conceited middle-class expectation (stemming, one imagines, from a coddled, sheltered existence having never spent a lick's time among the poor) that the poor should look the part otherwise, well, how it is possible that the poor could actually look like perfectly normal human beings?

Nevermind all this, no, these people are just the 'relative poor', and the real issues are matters of 'philosophy' and 'thought', and not, say, conditions of living and wellbeing that would literally drive one from one's home. Yeah, I stand by my initial comment that the OP should go fuck itself for its excremental detachment from reality. None of this is an argument by the way. It is dismissal and disdain. No joke. -

Currently ReadingMark Fisher - Capitalist Realism

Paolo Virno - When The Word Becomes Flesh: Language and Human Nature

Paolo Virno - Essay on Negation: For a Linguistic Anthropology -

The Collective Philosophy of 'Relative Poverty'I hate it when my refugees - who've left their home and everything and everyone they own and know behind - don't look the part of my poverty porn fantasies. Toilet rolls and clothes! The nerve!

Get fucked. -

The Philosophy of Language and It's ImportanceSure, but that's a lot different than the claim that linguistic analysis can potentially dissolve philosophy problems across the board. That philosophical inquiry is itself an abuse of language. — Marchesk

I agree. That's a bunch of wank. -

The Philosophy of Language and It's ImportanceI do actually think that time presents a coherent set of problems, though. — fdrake

As do I! The only thing I'd add is that a coherent problem is a grammatically well-formed one. This does not mean the problem of time is 'merely' linguistic: it simply means that it meets the minimal criteria of being a problem that can be addressed at all. It's like saying: "all problems of vision are problems of light": in some sense, this is true and undeniable - but it is also misleading. The disjunction between "all philosophical problems are linguistic" and "philosophical problems are real" is a fake one: philosophical problems are real - are only real - when they have a well-formulated grammar that makes sense of them. -

The Philosophy of Language and It's Importance"An explanation of time"; as if: "What is explanation of dog? Can science furnish explanation of dog? Or only philosophy give explanation of dog?"; Shitty Russians posing as philosophers of depth. A nice example of why any philosophical investigation that doesn't attend to language is doomed to failure.

-

Philosophical CartographyI understand that; but, you have limited the range by excluding/restricting another dimension — Posty McPostface

The second part of this sentence betrays the first as a falsehood. -

Philosophical Cartographythat a philosophy of valuation is itself a product of valuation. — csalisbury

If I understand you right, this is more or less what I think is the case: the problem of how to understand philosophy is itself a philosophical problem like any other: and as such, it's form is dictated to a certain degree by shape of philosophy itself, if I may put it that way. Basically I think any strict bifurcation between 'object level' and 'meta level' needs to be seriously put into question: any work of philosophy carries within in an implicit 'meta-philosophy' simply by virtue of it being philosophy to begin with. One can isolate, artificially, this 'meta-philosophy' and start comparing it, as if a car-catalogue, to other 'meta-philosophies', but I think this is a doomed exercise from the start: if you disconnect the principles that animate the philosophy from the philosophy itself, you're just playing a shell-game. It's 'philosophy on holiday' in the same manner that Witty referred to certain strains of analysis as 'language on holiday'.

The question then is not "how does this meta-philosophy compare to that meta-philosophy?", or "how do you compare between the two?", but does this approach to philosophy capture what seems to be its relevant aspects? Does it leave out anything of significance with respect to what it claims to capture? In other words: is this approach adequate to the very object it aims to specify? And this can be answered in all sorts of interesting and creative ways. For example, one thing a cartographic approach does is to temporally 'flatten' the field of philosophy: it makes Plato our contemporary no more than Foucault: time is given a particularly short shrift.

("The life of philosophers, and what is most external to their work, conforms to the ordinary laws of succession; but their proper names coexist and shine either as luminous points that take us through the components of a concept once more or as the cardinal points of a stratum or layer that continually come back to us, like dead stars whose light is brighter than ever. Philosophy is becoming, not history;

it is the coexistence of planes, not the succession of systems." (Deleuze, What Is Philosophy?)

Is this a 'price' worthy paying? Maybe there's an argument somewhere that it isn't. And that would be interesting debate because it would be motivated by the object itself: philosophy as problem. The only thing not to do here is treat 'meta-philosophy' as a closed field in itself, which'll invariably lead you to the sort of clinical hysteria of Psuedonym's questions: but how do you know??; what's the meta-meta-philosophy that authorizes you to say that? And the meta-meta-meta-philosophy of that? It's a very sad game that needs to be headed off at the pass. -

The Philosophy of Language and It's ImportanceI don't follow this, specifically, "it belongs to a wider set of practices and capacities which must also be grasped in their specificity." — Sam26

I simply mean that language is a practice like any other: playing football, walking a dog, brushing teeth; to use language is to do something. And 'doings' are not specifically linguistic. Moreover they can only be made sense of in wider contexts that might involve everything from economics to power relations to biology and so on. Language is embedded in a world, and to understand language we must understand the world. Witty would capture this in his recourse to his reference to the form-of-life in which language-games operate. -

The Philosophy of Language and It's ImportanceAll philosophical problems are linguistic in nature - to understand the problems is to understand the language; but the nature of language is itself not lingusitic: it belongs to a wider set of practices and capacities which must also be grasped in their specificity. So I don't see 'philosophy of language' as an autonomous discipline: to understand 'the philosophy of language' is to have to understand a great deal more than language.

-

Philosophical CartographyA map is a two dimensional depiction of a three dimensional plane or surface with features on it. — Posty McPostface

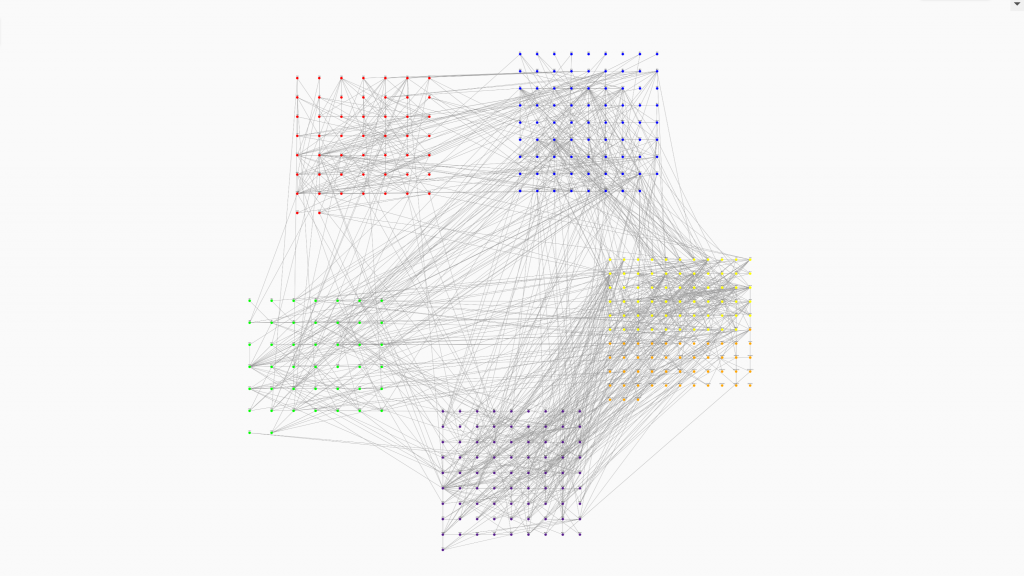

Because this is an incredibly simplistic, and dare I say, naive, definition of a map. Maps at their most abstract are simply ways of condensing and communicating relations though abstraction and, traditionally, though graphic and symbolic means. Not only is any reference to dimensionality entirely superfluous, but so too is any reference to 'planes and surfaces'. What I'm suggesting is that those means do not necessarily have to be - and in fact are often not - strictly graphic or symbolic. Or differently, they can in fact be properly symbolic: though words and even concepts. Here is a link to an interactive map of Spinoza's Ethics that was doing the rounds the other day, one which puts paid to any trivial understanding of maps as 'a 2d depiction of a 3d plane': http://ethica.bc.edu/#/visualization (or, for a 3D version: http://ethica.bc.edu/#/3d)

(sample)

(sample)

I'm simply suggesting to think of maps in a different medium, as the above in fact already is; and mediums are - as medial, as mediators - able to be swapped out, in the right circumstances. In fact, if you want to get 'technical' about it, there's a reason why, in math, another name for functions are mappings, insofar as they map domains to codomains - that is, insofar as they express a relation or set of relations in abstract terms (here is the function/mapping of a one-to-one function):

A function is, in this respect, nothing other than a particularly abstract map: there's an argument to be made that math too is nothing other than a cartographic exercise. The difference here to a 'traditional map' is that the relations expressed are not geometrical but simply numerical (geometry in fact being a more restricted, less generic form of math). Again, all I'm suggesting is that the same thing can and does occur at the level of the conceptual. -

Philosophical Cartographythere being more anatomical features than an anatomist's painting of the human body entails. — Posty McPostface

And that point had to do with the fact that maps must always be pluralized to be of better use: that anyone seeking 'one map to rule them all' was seeking after an illusion; and thus to place the accent on 'there being more' than the map can express is to miss the point entirely: the desideratum is to eliminate - ruthlessly - features: we don't want more least the map loses its efficacy. That the map is not the terrain is the best and most useful thing about maps. Those who think this expresses an inadequacy about maps don't understand, or have been seriously mislead about the point of a map. -

Philosophical CartographyIt's not 'trying to capture philosophy' as if to represent or reconstitute it in some way or another - it is philosophy. I'm not convinced you've read and understood the OP.

-

Philosophical CartographyChanges in dimensionality don't result in increases of information available to the total state space — Posty McPostface

This isn't a question of information 'availability' as it is expressive power so you 'getting technical' is you talking about something else entirely and again, irrelevant to the discussion.

By sheer irony, 'state space', by the way, is a concept that designates a multi-dimensional array that that can be 'instantiated' in physical dimensions far below the number of dimensions in the actual array (hence hard drives): which is exactly why the changes in visual dimensionality are - within certain bounds - entirely irrelevant. The 'state space' of writing is orders of magnitude larger than that of a picture because it can accomodate - in a way that pictorial representation can only dream of - both abstraction and hierarchical embedding of reference within it.

Streetlight

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum