-

More Is Different@Pierre-Normand, So I just finished reading the Crowther paper and damn it's excellent. It vindicates, I think, my avoidance of talking about emergence in a thread largely dedicated to reductionism, and makes me really want to read the Butterfield papers she referenced. I've actually come across both Batterman's and Morrison's papers before (the ones she critiques for giving too negative a definition of emergence as 'not-reduction'; Massimo Pigliucci has discussed both on his blog), and I really like her angle of critique. Her discussion of EFT was also excellent and blissfully clear, and the whole thing just helped me clarify alot of the conceptual issues I had with thinking about these issues. Awesome.

-

Space and Time, Proteins and PoliticsAlso, just had a curious thought relating this idea of chronopoltics to the "X" History Month, where X is a historically/currently excluded minority (e.g. Gays/Blacks/Women), in which our collective society recognize this community and prominent individuals within the it, and celebrate them in ways that range from meaningful to cheap Capitalist cash-grabs, but ultimately relegate the importance and dignity of such communities to merely one month out of the year, like some annual ritual where, for a paltry 30 days (28 for Black America), we celebrate the contributions of certain communities, then return to "normal". No doubt this is not a novel idea in-itself, but I think it does play into the concept of chronopoltics. — Maw

This is perhaps a worthy debate topic of it's own, but the distastefulness - If I can call it that - of having something like a Black History Month or a Gay Mardi Gras is, I think, part of the point. It's probably true that we shouldn't need to have an X history month of whathaveyou, but, if I may put it paradoxically, the fact that we shouldn't need to have it is all the more reason to have it. But yes, the larger point is that paying attention to the politics of time (and space) allows one to see, or rather, be more sensitive to factors that may not otherwise come to one's attention in explaining particular disparities or differentials in power and/or access to resources. -

More Is DifferentI read this when you wrote it and thought I understood what you meant. I thought your point was that a situation like QM, which applies at all scales but who's effects are only significant at atomic scales, is not a true example of emergence. — T Clark

One thing to note is that I've been quite careful to avoid the word 'emergence' when talking about alot of this stuff (take a look, I don't even use the word at all!). All I was doing with the QM comment was insisting that one be careful about the kinds of conclusions that one draws from the insistence of context: just because everything is context-bound does not mean that one can entirely disregard the functioning of things at a 'lower level' in the context of a higher one: with QM, just because quantum effects are no longer as manifest at macro scales does not mean that QM 'stops functioning' at macro scales, only that those effects are so small as to be rendered (for the most part) inconsequential. I say 'for the most part' because as P-N pointed out, if you look for quantum effects at macro scales, you will still find them.

Crowther's point, as I read it, is similar: at low energies, BCS theory captures the dynamics of superconductive systems even though it doesn't take into account high-energy interactions that take place all throughout the system. This doesn't mean that those high-energy interactions - interactions between electrons - somehow 'cease to exist' or whathaveyou, only that, at the level of explanation we are interested in, those interactions are not relevant. Crowther's point goes further than mine though because she actually provides a reason why this is so: at low energies, we can simply measure interactions due to phonon exchanges in order to capture the dynamics, and importantly, phonons only exist at low energy levels. This is where questions of emergence might start to become relevant, but it wasn't necessarily what I was concerned with in my own comments prior. -

More Is DifferentBut words like 'Absolutism' and 'Relativism' are just words, nominations. What does it matter if you call something 'absolutism' or 'relativism'? You haven't specified the difference these differences make. As for the cat, what about it? Again, what's the relavence? I think it would be more helpful if you elaborated the stakes involved in invoking these things.

-

Society of the Spectacle'Dialectical Materialism' is one of those phrases that has always struck me as meaning whatever one wanted it to - an empty signifier, as it were, open to accepting whatever meanings one were to foist on it. It hasn't been very relavent to my own interests so far, so I'm relatively indifferent to it.

-

Space and Time, Proteins and PoliticsLefebvre's The Production of Space is one of my favourite books ever, and the work of Doreen Massey (Space, Place and Gender) was transformative in my understanding of how space is infused with power, and hence, a site of political contestation. One of the things I'm trying to do in the OP is, at it were, sneak these perspectives in through the backdoor with a case study from the sciences, and poke at Kant in the process, which is why I briefly mentioned the role of political geography in the OP - I actually had Harvey in mind here, although you're right that I probably should have spoken about human geography instead. To the idea of chronopolitics one could perhaps add the notion of a cartopolitics...

-

Society of the SpectacleAlso, I very much appreciate your reading of social media in Debord's terms - obviously something he couldn't have anticipated - and I think your rereading of Marx's M-C-M' relation and what happens when potential itself is commodified is awesome. Very cool.

-

Society of the SpectacleFinished chapter 1 as well. An interesting read so far. The two most immidiate points of reference that come to mind are Zizek and Agamben. (1) Re: Zizek, I haven't listened the the podcast yet, but one of the concepts that Zizek makes use of is Robert Pfaller's notion of interpassivity: interpassivity is the phenomenon of letting other things do our work or even our feelings for us. Zizek uses the example of both canned laughter and the Greek chorus to make the point:

"Let us remind ourselves of a phenomenon quite usual in popular television shows or serials: 'canned laughter'. After some supposedly funny or witty remark, you can hear the laughter and applause included in the soundtrack of the show itself - here we have the exact counterpart of the chorus in classical tragedy; it is here that we have to look for 'living Antiquity'. That is to say, why this laughter? The first possible answer - that it serves to remind us when to laugh - is interesting enough, because it implies the paradox that laughter is a matter of duty and not of some spontaneous feeling; but this answer is not sufficient because we do not usually laugh.

The only correct answer would be that the other - embodied in the television set - is relieving us even of our duty to laugh - is laughing instead of us. So even if, tired from a hard day's stupid work, all evening we did nothing but gaze drowsily into the television screen, we can say afterwards that objectively, through the medium of the other,· we had a really good time." (Zizek, The Sublime Object of Ideology). While not exactly congruent, the 'other' here that Zizek speaks of very much functions in the way that I think the spectacle does in Debord: it appropriates 'activity' to itself, even as it renders passive the entire social order. The distinction Zizek draws between the psychoanalytic conceptions of the ideal-ego and ego-ideal (also in the Sublime Object) also seem relevant here, but I only mention these as bookmarks for future engagement.

(2) Agamben is my other resonance here, and while I can't really summerize Agamben's position, his entire philosophical oeuvre is centred around the theme - developed by Debord - of transposing what was once a separation between the worldly and the divine into a separation 'within human beings'. In one of my favourite books by Agamben, The Kingdom and the Glory, Agamben's devotes a whole analysis to how 'glory' - the glory sung of God by the angels - serves to cover up the 'emptiness' of the articulation between the divine and the earthly. He then transposes his theological analysis back onto the role of media which serves the role of 'glory', and, one is tempted to say, spectacle. I didn't recognise the Debordian resonance of this analysis when I first read it, but it's cool to see it in retrospect (Agamben has written about Debord explicitly elsewhere, and you can find letters that Debord wrote to Agamben, online, regarding some of that writing).

So the highlights so far are the elaboration of the themes of passivity and (immanent) separation, which strike me as key terms when coming to grips with the elaboration of the society of spectacle. There's also a strong resonance with Jodi Dean's notion of communicative capitalism (a gloss: "a constitutive feature of communicative capitalism is precisely the morphing of message into contribution…The message is simply part of a circulating data stream. Its particular content is irrelevant. Who sent it is irrelevant. Who receives it is irrelevant. That it need be responded to is irrelevant. The only thing that is relevant is circulation, the addition to the pool. Any particular contribution remains secondary to the fact of circulation”...), but I might develop that in another place. -

Word of the day - Not to be mistaken for "Word de jour."Yep! Also sangiovese, one of my favourite drops of red. Also also - and this is the religious reference I was actually looking for but couldn't remember - it's the root of 'holy grail', sang-real, or 'royal blood'.

-

Space and Time, Proteins and PoliticsThat's actually a really interesting example because it allows me to make a distinction I hadn't thought of before: chronopolitics as tactic and chronopolitics as end. To explain: I think the refrain that 'now is not the time for politics' is indeed a political uptake of time (it's a contest over time, it's use, it's meaning - a time for mourning or a time for activism? Both? Neither?), but its more an means to an end than an end itself. What I had in mind was instead chronopolitics as end - the fight for a 5 day workweek and an 8 hour workday was not so much tactical as it was an end in itself: the contest over time just is the point of that political fight.

Another example which imbricates the two (space and time, tactics and end) might be the fight - particularly relavent in Australia, or Sydney rather (and San Fransisco now I think about it) - over affordable housing. The fight for affordable housing is more than an economic one: it is also a fight over differential access to 'life resources' - work, public transport, retail outlets and spaces for socialization. It may cost less to live far away from the/an urban centre, but one pays the price in both space and time, literally. Those that can afford housing close to life resources are richer not only in monetary terms, but spatial and temporal ones too. So just by thinking in terms of space and time, you actually get to tie in a whole range of other considerations too: demography, geography, economics, and public policy, to name a few.*

And this should make sense at the philosophical level: again, Kant was right to call space and time conditions of experience, but that they are conditions of all experience also means that everything has an irreducible temporal and spatial dimension that can be taken into account. To think in terms of space and time inevitibly means to think also in terms other than just space and time.

*An additional thought: in the US - although not only in the US - such considerations are also massively bound up with questions of race, insofar as the legacy of redlining - 30 years of racial neighbourhood segregation - has effects that still play themselves out today, effects that I think were perhaps even more consequential - although far less talked about - than school or other institutional segregation. -

My moral problemJust make sure you design the exhaust port so that a well placed proton torpedo can bring it all down.

-

Space and Time, Proteins and PoliticsThanks! I don't know about Leibniz though - time and space remained 'well founded phenomenona' for him and as such don't really have any ontological status in his monadism apart from that. I think he was right to relativize both to 'objects' (I'd prefer to say processes) against Newton's (and thus Kant's) absolutization of them, but I think he was wrong to infer that this reletivization merely rendered them 'well-founded phenomena'. Basically, I want to have my cake and eat it too: I want to say that space and time are both relative and real. The 'trick', to the extent that there is one, is to also accord this same status to 'objects' - or again, processes - as well: there is nothing that isn't relative - nothing that isn't context-bound, nothing that doesn't function differentially - that is also real, a part of reality.

In the case of the spatio-temporal regulation of protein folding for instance, while the exact mechanisms are still being worked out, the dynamics have to do, ultimately, with physical forces acting on the amino acids - forces like energy and chemical differentials/gradients, hydrophobic and electrostatic forces, binding and bending energies, as well as ambient conditions like pH, temperature and ion concentration. As Peter Hoffmann puts it, "a large part of the necessary information to form a protein is not contained in DNA, but rather in the physical laws governing charges, thermodynamics, and mechanics. And finally, randomness is needed to allow the amino acid chain to search the space of possible shapes and to find its optimal shape." - The 'space of possible shapes' that Hoffmann refers to is the so-called 'energy landscape' that a protein explores while folding into its final shape, where it settles into energy-optimal state after making it's way through a few different possible configurations (different configurations 'cost' different amounts of energy, and cells regulate things so that the desired protein form settles into the 'right' energy state). (Quote from Hoffmann's Life's Ratchet).

Anyway, the point of that mini-lesson in protein folding is that while the spatio-temporal dynamics of the foldings are themselves regulated by all these different mechanisms (that is, while spacing and timing are still relative to the biodynamics), those dynamics nonetheless exert real effects of their own. If the timing is not right, a protein will misfold, and you'll end up with Parkinson's or Alzheimer's. The same with the specific spatial topologies. The whole processes is a 'holistic' one, working in concert, where each process - of which spatialization and temporalization are two among others - is as vital to the result as every other. There is a reciprocity of condition and conditioning. This is why I absolutely deny that anything in particular is ontologically fundamental, as it were. In fact, this entire thread was motivated by some thoughts in my last thread in which the entire point was to argue against the idea that any 'level' of reality would be more fundamental than any other (here, if you want the context).

Note also that by Idealism I don't mean anti-realism, but more properly Idealism in the Platonic sense, where one Idealized strata of reality is taken to contain, on it's own, the governing principles of the rest of the universe (Forms or εἶδος - or, in their modern day guises, 'atoms' and 'fundamental particles'). -

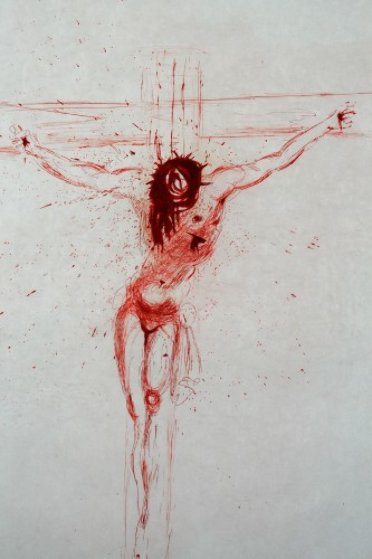

Word of the day - Not to be mistaken for "Word de jour."Because I just so happened to use it:

Desanguinate: to remove the blood; to drain one of blood or hope. Or it's opposite -

Ensanguination: to stain with blood, to make of something a blood-red colour. Both derivatives of -

Sanguine: hopeful, social, full-blooded or blood-red in colour. Can have religious connotations as well, as when one speaks of de sanguine Christi, the blood of Christ, hence Dali's "Christ (Sanguine)":

-

Space and Time, Proteins and PoliticsKant was right, at the very least, about the 'necessity' of space, but was wrong, I think, about his conceptualization of space (and time) as merely formal. That is, I grant Kant space is indeed a condition of cognition, but refuse to follow him in accepting it's wholly a priori nature. Part of what I'm trying to get at in the protein folding example is that fact that space needs to be thought in the plural, as spaces (the kind of space each amino acid occupies - it's topological relations with the elements in its vicinity - matters to the final protein form), or even rather as a verb: not 'space' as an abstract noun but spac-ing as a verb, as something that happens, the 'event' of spacing in the folding of the protein as carrier of information. The same can be said of time, which I why I similarly speak of 'timing' rather than Time in the substantive (a large deal of the confusion over space and time is grammatical, I suspect).

The basic idea is to get rid of conceptions of space and time which treat either as a kind of mere 'container' in which things happen, but which are themselves not part of 'what happens', as it were. It's to insist on the irreducible reality of space and time, their tangibility, their affective force - in short, their materiality - as something that cannot be considered apart from what happens: in this case the morphogenesis of the protein. Also, if you remember the Guess book, he also specifically writes of how timing in politics is one of the biggest factors when conducting any political analysis, but that it's so often forgotten in the High Theory of Political Philosophy, which aims, like all idealism, to desanguinate the world of both space and time. -

The language of thought.Very cool (that may have just been the only psych paper I've read in my life from start to end, lol).

-

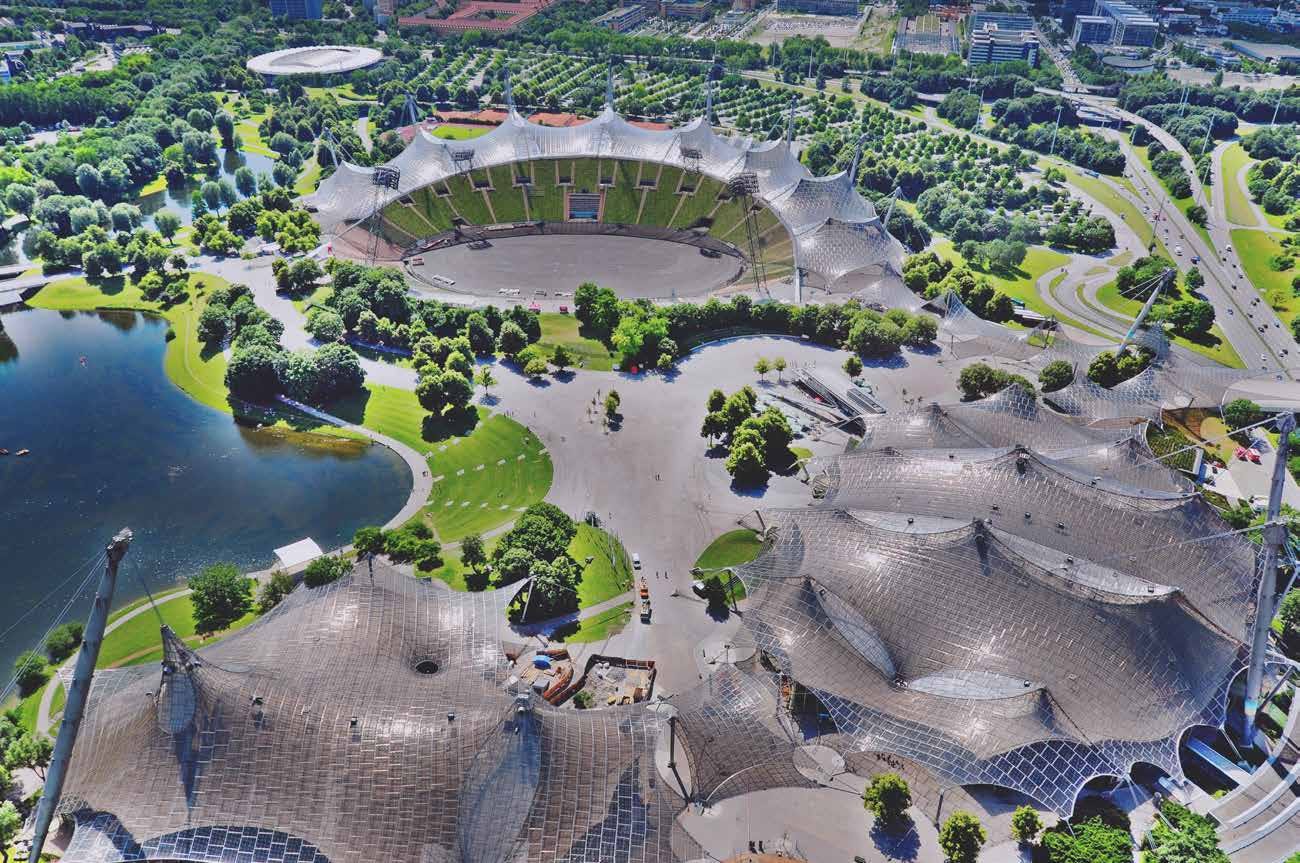

Beautiful Structures

This is the Olympic stadium in Munich, designed by Frei Otto. Otto designed his 'sails' by using soap bubbles to model the surface area so that he could achieve the most efficient use of materials. This is architecture literally modelled off nature.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2004/oct/04/architecture -

The language of thought.Potentially relevant bit of science reporting:

https://arstechnica.com/science/2018/03/although-they-cant-tell-us-about-it-infants-can-reason/

"The researchers claim that this increased pupil dilation [in infants] “suggests increased cognitive ability, possibly due to inference-making.” Why do the researchers think this? They used millennials as a control. Millennials can, usually, tell us what they are thinking—that’s how we know they have reasoning skills. But when they are presented with the same movies of plastic dinosaurs and flowers in cups and boxes, their pupils likewise dilated only when they had to infer which toy was where. (They also stared longer at inconsistent outcomes.) Téglás and co. conclude that precursors of logical reasoning are thus independent of, and even preliminary to, language."

@creativesoul You might like this too. -

More Is DifferentThe point is not to reconstruct the universe, it is to see it as it really is. — Caldwell

Yes, but who doesn't claim to 'see things as they really are'? This is why I insisted, in the OP, on the rhetorical trope of the 'is only...' when it comes to reductionism. 'Is only' excludes, it denies, as I said, the informational capacity of context, it rules things out so as all the better to rule (one) thing(s) in - atom, mind, God, etc. It is simplicity bought at the price of simplification, in the most pejorative sense of that word. -

More Is DifferentA couple of weeks ago I started a discussion - "An attempt to clarify my thoughts about metaphysics." I wanted to lay out my thoughts about the difference between questions of fact and questions of what I called "metaphysics." One of the upshots of the discussion is that I think calling it metaphysics is probably not right. At least it's misleading. The questions I was interested in were those that are not matters of fact, but are more a matter of choice about how you want to look at things, e.g. is there such a thing as objective reality? is there an objective morality? Is there free will? I have always said that type of question does not have a yes or no answer. It's a matter of usefulness, not truth.

The discussion we are having now is making me rethink that. — T Clark

Excellent :D This is, obviously, a different topic, but I think you're on exactly the right track; I don't think truth has ever been an index of philosophy, nor do I think it ought to be. As Deleuze says, philosophy lives and breathes not on truth, but on the Remarkable, the Interesting, and the Important: categories of sense, of significance. I would quibble about the the idea that it's a matter of 'choice' - philosophy or 'metaphysics' always arises, for me anyway, out of the necessity of responding to a problem, where the problem - whatever it is - is immanently defined by the solution which addresses it. But this is somewhat off-topic. -

More Is DifferentI'm glad you're finding some of these threads useful, or at least provocative! Note that the thread on gene expression is basically an example or a 'case' of the more generalized principles I've tried to outline in this thread: context always modifies the operation of the elements so contexualized - genes will express differently depending on 'context' (where here 'context' serves to cover a shit ton of interesting biology, only some of which I broached in that previous thread). And note also that the stuff I did speak of in that thread - re: gene networks - didn't even begin to broach the question of protein folding and the secondary and tertiary structures (along with their regulation) that also influence the production of a protein. The path from DNA to trait is basically an entire biological adventure (i.e. DNA = organism = wrong!)

Isn't it more than just philosophical ontology? — T Clark

As in? -

More Is DifferentThinking a little about this in terms of information, part of what it means to subscribe to reductionism is to say that context contains no information, or rather, cannot function informationally. For example, in biology, people have had to work hard to demonstrate that information about gene expression (what DNA codes for) and heredity (what gets passed down from one generation to the next) is not contained in the genes alone: DNA alone is not sufficient a mechanism, on it's own, to constitute an organism. This is the case both ontogenetically (development of a single organism though it's life) and phylogenetically (evolution at the level of a species, from one organism to it's offspring).

Ontogenetically, the exact protein a DNA will code for will depend not only on it's so-called 'primary structure' (the precise order of amino acids coded for by DNA sequences), but also it's 'secondary' and 'tertiary' structure: that is, the local geometries of any one protein: the spacing between amino acids (are they folded into helixes or pleated into sheets?), as well as the timings and temporal sequences in which the protein is 'folded'. Space and time literally carry information regarding the 'end result' of what DNA codes for, in a way that is not itself contained in the DNA sequence (usually regulated by chemical gradients, electrical differentials, and maybe some other mechanisms).

Phylogenetically, what is 'passed down' from parent to child is also not 'only' contained in the DNA. Instead, information is carried by the entire 'developmental system', i.e. the entire environment in which the DNA is passed down, such that it too carries the information necessary for the development of the offspring.

In both cases, reductionism would require denying the informational role that context plays - 'context' being space, time and other mechanisms of heredity which specify how an organism will develop through it's lifetime. And again, to be against reductionism here is just to be for science, not against it; at least, it is to hew closer to the discoveries of science than any extra-scientific metaphysics which is foisted onto it from the outside. This obviously doesn't answer the symbol-grounding problem which you asked about, but it does imply thinking about 'symbols' differently: as not carriers of information in their own right, but as resources that need to be thought about in terms of wider, context-bearing processes. -

More Is DifferentYeah, having someone like Weinberg doesn't help, but I suspect that the basic answer is that it's not as 'pretty'. To say that everything is just 'atoms in motion' is an incredibly attractive thesis, a powerful-looking, parsimonious 'explanation' for things that absolves one from going out there and doing the hard work. It's good PR ('the God particle', 'Grand Unifying Theory', etc), and moreover, it has a long and rich history, which used to culminate in 'God' instead of 'atom'. But both are idealist claptrap.

The other reason is that science is, in general, methodologically reductionist: an experiment has value precisely to the extent that 'context' is, as much as possible, controlled for, such that we can track one variable while holding equal an entire background of other variables. 'Context' is exactly what you exclude in experimentation, all the better for experimental success. This is less a vice than a virtue however, and is one of the reasons science is so very powerful. In other words, reductionism works. The problem is when this necessary methodological reductionism is translated into, as it were, ontological premise.

So, just because microphysical phenomena can be effectively amplified by macroscopic apparatuses that interact with them, the finiteness of Planck's constant (i.e. the fact that it's larger than zero) has direct consequences for the structure of the phenomena that we can observe at the macroscopic scale, such as interference patterns. This constraint also undercuts the idea that the microscopic events that are being probed have their determinations independently from the instrumental contexts in which they are being measured, or so have Bohr and Heisenberg argued. — Pierre-Normand

Yeah, this makes alot of sense, and the implications of this kind of thinking are something I'm always keen to try and tease out. Also, Weinberg's 'arrows of explanation' are pretty much exactly the 'one way street' explnations I was aiming at in the OP. -

More Is Different"I had found that phenomenology and hermeneutics were helpful in making sense of the distinction between classical physics and post-classical physics of relativity and quantum mechanics because these new philosophies had the capacity to explore the latent significance and function of context in both scientific traditions; ‘context’ was arguably the central innovative component of these physical theories that had revolutionized 20th century physics." — Pierre-Normand

It's odd isn't it? I mean, the idea that context matters is so simple an idea, yet it is routinely ignored despite it. And it provides such a simple retort to those who believe in atoms or genes or whathaveyou as constituting any kind of 'fundamental ground' for the rest of the world. Yet the only thing that's 'fundamental' is that everything can function differentially, depending on the context which explicates it:

"What counts is the question: of what is a body capable? And thereby he [Spinoza] sets out one of the most fundamental questions in his whole philosophy (before him there had been Hobbes and others) by saying that the only question is that we don't even know what a body is capable of, we prattle on about the soul and the mind and we don't know what a body can do. But a body must be defined by the ensemble of relations which compose it, or, what amounts to exactly the same thing, by its power of being affected." (Deleuze, Lecture on Spinoza). -

More Is DifferentSerious. As I said, QM is just the way things are. I don't feel any ontological agita. Why would you expect things to behave the same at atomic scale as it does at human scale. I hate it when people, even physicists, get all excited and talk about "quantum weirdness" as if they're Neil DeGrasse Tyson, that son of a bitch. This stuff makes me rethink how the universe works. — T Clark

Ooh, I see what you mean. But yes, all investigation ought to be scale specific - which is not to say that it isn't interesting or important to understand QM! In fact, even a minimal understanding of QM helps to explain why QM isn't super important at macro scales on the basis on QM itself. You don't need any fancy philosophy here at all. The first point and most important point to note is that QM does in fact apply at all scales. The question is over the effects of QM at macro scales, and it's that effects that are negligible. Why? First because Planck's constant ('h') is so, so tiny: 6.626176 x 10^-34 (as Karen Barad puts it, if you convert Planck's constant into a length, 'this length is so small that if you proposed to measure the diameter of an atom in Planck lengths and you counted one Planck length per second, it would take you ten billion times the current age of the universe."). And the second reason is that quantum effects take place at the order of the ratio between Planck's constant and mass (h/m): for objects with tiny mass - like an atom - that ratio is high. For objects with large mass, that ratio basically becomes negligible, but never non-zero.

Barad: "There is a common misconception (shared by some physicists as well as the general public) that quantum considerations apply only to the micro world. Some people think that the fact that h is very small means that the world is just as Newton says on a macroscopic scale. But this is to confuse practical considerations with more fundamental issues of principle. ... The fact that h (Planck’s constant) is small relative to the mass of large objects does not mean that Bohr’s insights apply only to microscopic objects. It does mean that the effects of the essential discontinuity may be less evident for relatively large objects, but they are not zero. To put it another way, no evidence exists to support the belief that the physical world is divided into two separate domains, each with its own set of physical laws: a microscopic domain governed by the laws of quantum physics, and a macroscopic domain governed by the laws of Newtonian physics". (Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway) -

Beautiful StructuresDid you read "Leiningen Versus the Ants?" It was standard fare for high school students in the US. It's a short story about a plantation owner's fight against army ants in Brazil. Pretty scary. — T Clark

Woah. Just read a synopsis. Pretty scary indeed! -

Beautiful Structures

The most terrifying bridge in the world. This is a fire-ant bridge, constructed to get ants across bodies of water. Incidentally, here is a fire-ant raft, just in case you thought you could sleep well tonight:

-

More Is DifferentPhenomena and processes are 'complex' in the philosophical sense (of course, that is also true if strictly science). Reductionism in the true sense of existence denies the complex and what's left is ultimately the indivisible something -- say an atom. I don't suppose the (old) traditional reductionists would want to change the entire meaning of their endeavor. Reductionism is about what is ultimately cannot be denied.

I realize I am sort of defending the traditional reductionism even through I am not a follower of this school of thought. — Caldwell

Yeah, it's actually a really hard mindset to shed, and it inevitably creeps back when one isn't paying attention. It doesn't help when people talk about genes as 'the secret to life' or atoms as 'the building blocks of the universe', and so, as is often done in pop-sci presentations of these topics. It makes for good, bold headlines, but for horrible philosophy - not to mention science! In fact, the oddest thing about such reductionist programs is that, taken to their logical conclusion, the ability to reconstruct the universe from first principles is idealism in it's most extreme form; they literally 'vacate the world of its content' as it were, giving up empiricism - the very loadstone of science - for ideality. Yet this almost entirely antiscientific POV is what is almost universally associated with so-called 'hard core science'. It's both bizarre and saddening.

'Complexity' - a different, but related topic - is also another one of those concepts that is generally often defined in vague, imprecise ways (usually circularly as well: 'what is complex is what cannot be broken down into simple parts.... which is to say that it is complex'; or the even worse and more fuzzy 'the whole is greater than the sum of its parts'.). The only definition of complexity with rigour that I know of is Robert Rosen's, which 'relativizes' complexity to our ability to model a particular system, and stipulates that a complex system is one with no 'largest model' - no single model that can capture all the dynamics of such a system. There's a nice summary of it here.

I can't imagine anything more radical. Quantum mechanics is easier because I don't have to understand it, I only have to believe that things behave the way scientists say they do.

— T Clark

-

Beautiful StructuresIt's actually an abandoned termite mound, taken over by fireflys. They're using it to catch prey!

-

Society of the SpectacleDamn you. I've had Spectacle sitting under my bed for a few years now and now you're going to make me read it along with you :<

-

More Is DifferentHere is one of the clearest primers I know, although it explains it through reference to Merleau-Ponty.

But yeah, the Anderson paper is awesome. I couldn't not talk about it.

I think I should have named this thread something like: Reductionism is Bad Science or somewhat. -

More Is DifferentPerhaps you could clarify/answer the symbol grounding problem Floridi raises (i.e., "how data can come to have an assigned meaning and function in a semiotic system like a natural language")? — Galuchat

I have vague intuitions about this question, but I'm still lacking the conceptual clarity I need to really address it properly. There's a whole nexus of terms - around embodiment, gesture, sense, and asymmetry that I need to do more research on, and am planning to do in the future. -

More Is DifferentHah, I've read that Floridi book - pamphlet, really - but unfortunately found it so painfully average that I think that connection would have escaped me entirely. I can't speak for Newell, but the idea that "lower levels of description always underdetermine higher levels" sounds about right.

-

Identity Politics & The Marxist Lie Of White Privilege?Me, mock? No, no, pathological paranoia is a serious problem that should be treated with the gravity it deserves!

-

Identity Politics & The Marxist Lie Of White Privilege?Lesson #1 in pathological paranoia: go around asking how we know something is not the case: how do we know the royals aren't really blue bloods? How do we know that aliens don't really live among us?

-

Identity Politics & The Marxist Lie Of White Privilege?I've seen this being shared around my circles too, and I think the most devastating passage is this one: "Activism, then, is arrogant brats holding “paper on sticks,” a peculiar and appalling phenomenon he believes started in the 60s. Nevermind that what he is talking about is more commonly known as the Civil Rights Movement, and the “paper on sticks” said “We shall overcome” and “End segregated schools” on them. And nevermind that it worked, and was one of the most morally important events of the 20th century. Peterson, who is apparently an alien to whom political action is an unfathomable mystery, thinks it’s been nothing but fifty years of childish virtue-signaling. The activists against the Vietnam War spent years trying to stop a horrific atrocity that killed a million people, and had a very significant effect in drawing attention to that atrocity and finally bringing it to a close. But the students are the ones who “don’t know anything about history.”

This resonates in particular with me because I think what strikes me more and more about Peterson is just how he decontextualizes - consciously or unconsciously, I don't know - so much of what he talks about. And in the absence of context, alot of what he says can indeed come off as eminently reasonable. But then when you realize what he's trying to do with those comments, what they are aimed at - once they are recontextualized, the comments take on a much darker hue. Hence:

"I think it’s worth remembering here what anti-discrimination activists are actually asking for: they want transgender people not to be fired from their jobs for being transgender, not to suffer gratuitously in prisons, to be able to access appropriate healthcare, not to be victimized in hate crimes, and not to be ostracized, evicted, or disdained. Likewise, the social justice claims on race are about: trying to fix the black-white wealth gap, trying to reduce racial discrimination in job applications, trying to reduce race-based health disparities and educational achievement gaps, and reducing the unfair everyday biases that make life harder for people of color. This is the sort of thing the left is focused on." But you wouldn't know this, listening to Peterson.

Streetlight

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum