-

Streetlight

9.1kKant famously understood both space and time to be forms of sensibility, the envelopes though which the 'contents' of sensibility - the 'manifold of intuition' - present themselves to our cognition. This idea of space and time as somehow formal, as 'external' to the 'contents' of the world has a long and rich history, in which space and time are often treated as mere formalities, lacking in any particular force or tangibility of their own. In the case of time, this shows itself most obviously in certain scientific experiments, in which time is treated as an independent variable: 'independent' insofar as it is not affected by the experiment itself, but is that 'along which' changes in the dependant variable (say, mass, speed or distance), are measured.

Streetlight

9.1kKant famously understood both space and time to be forms of sensibility, the envelopes though which the 'contents' of sensibility - the 'manifold of intuition' - present themselves to our cognition. This idea of space and time as somehow formal, as 'external' to the 'contents' of the world has a long and rich history, in which space and time are often treated as mere formalities, lacking in any particular force or tangibility of their own. In the case of time, this shows itself most obviously in certain scientific experiments, in which time is treated as an independent variable: 'independent' insofar as it is not affected by the experiment itself, but is that 'along which' changes in the dependant variable (say, mass, speed or distance), are measured.

(Here is a simple graph of acceleration, in which the distance traveled by some object increases as time - which remains constant - plods along)

But it only takes a moment's reflection to realize that this understanding of space and time is entirely wrong. The understanding of space and time as merely formal belies the fact that the particular 'characteristics' of space and time (spaces and timings, it might be better to say) play huge roles in how things come about. Space and time are as much 'content' as they are 'forms', in other words. To speak intuitively, everyone knows that timing matters: the fact that I do something now, and not later (leave the house to catch a bus, say), will have a marked and significant effect on the outcome of a situation (me making it on time to work). Similarly, the fact that work is far from me and not down the road, will have a significant impact on how I (ought to) plan my day. When and where things are in relation to each other, geometric/topological and temporal distributions, matter: they in-form outcomes.

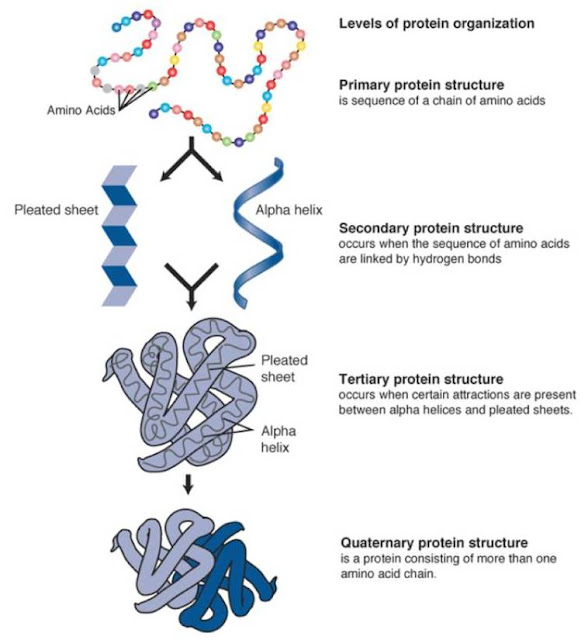

At a more technical level, one can see the importance of this - the importance of treating space and time as 'content', as carriers of information - when it comes to protein folding. Proteins are macromolecules (big molecules) made up of amino acids, which are themselves coded for by DNA (DNA -> amino acids -> proteins). Now, the most straightforward (and misleading) understanding of protein formation is to say that proteins are 'programmed' by DNA: input a specific sequence of DNA, output a specific protein (this is literally the job of DNA). But this is not quite right. For DNA sequence (or rather, amino acid sequence) only specifies what is called the 'primary structure' of the protein: the literal order of molecules that make up the entire chain of molecules. Equally important however, are the 'secondary' and 'tertiary' structures of the protein molecule, the specific shapes into any protein 'folds' itself into (for example, helices or pleated sheets), as well as the 'timings' or temporal order in which specific folds in a protein happens (it may be important to 'fold' the helix before the sheet, for example):

A protein that has the right order of amino acids (the right primary strucutre) but the wrong spatio-temporal distributions (secondary and tertiary structures) will fold 'wrongly': they will or can lead to all sorts of health problems. Importantly, one cannot reconstruct or predict what protein will form by knowing nothing other than the DNA sequence alone. You can't read back from protein to DNA, as it were. The philosophical relevance of this is that, when it comes to protein folding, space and time carry information, or rather, spacing and timing, specific geometries and specific timings have effects that cannot be 'read off' primary structure alone. Another way to put this is that spacing and timing are material: they are not idealized 'forms', but forces in their own regard, worldly 'contents'.

One 'macro-world' implication of treating space and time as worldly forces, is to recognize that this entails the need to pay attention to the role of both in, say, politics. Sticking with time, Levi Bryant, for instance, speaks of a 'chronopolitics', in which claims upon our time constitute an entire order of political contestation: the fight for a 5 day work week in the wake of the industrial revolution for instance, was nothing other than political contest over time. On the order of space, the entire field of political geography studies how spatial distributions unevenly effect societal relations - economic, temporal, demographic, and otherwise. -

TimeLine

2.7kThis is cool :ok:

TimeLine

2.7kThis is cool :ok:

When I was studying my PhD, I was analysing voter demographics in Turkey and trends to analyse topological 'swings' - or relational thinking - toward far-right ultra-nationalism in specific geographic regions, and weaving in historical or abstract properties relative to religious influence - such as the 'boundaries' of the former Ottoman Empire and the symbolic return of a neo-colonial past - all contained contingent properties. To help me formalise something accurate, I took a Cartesian angle (hah) where the physics of these properties were “extension in length, breadth, and depth which constitutes the space occupied by a body, is exactly the same as that which constitutes the body” (body being Turkey) and thus geometrically aligned reference points, kind of like your DNA example that make this complex whole tangible. Political science is kind of like the physics of abstract properties, taking in the Hobsbawm' view that political ideologies are imagined but that distributes and negotiates 'real' physical power through this network. I am not entirely sure whether there is any dichotomy here at all, where space enables us to understand time and motion; where as Kant said: "Space is a necessary a priori representation that underlies all outer intuitions. One can never forge a representation of the absence of space, though one can quite well think that no things are to be met within it" where intuition is an objective representation, something measurable. -

Streetlight

9.1kKant was right, at the very least, about the 'necessity' of space, but was wrong, I think, about his conceptualization of space (and time) as merely formal. That is, I grant Kant space is indeed a condition of cognition, but refuse to follow him in accepting it's wholly a priori nature. Part of what I'm trying to get at in the protein folding example is that fact that space needs to be thought in the plural, as spaces (the kind of space each amino acid occupies - it's topological relations with the elements in its vicinity - matters to the final protein form), or even rather as a verb: not 'space' as an abstract noun but spac-ing as a verb, as something that happens, the 'event' of spacing in the folding of the protein as carrier of information. The same can be said of time, which I why I similarly speak of 'timing' rather than Time in the substantive (a large deal of the confusion over space and time is grammatical, I suspect).

Streetlight

9.1kKant was right, at the very least, about the 'necessity' of space, but was wrong, I think, about his conceptualization of space (and time) as merely formal. That is, I grant Kant space is indeed a condition of cognition, but refuse to follow him in accepting it's wholly a priori nature. Part of what I'm trying to get at in the protein folding example is that fact that space needs to be thought in the plural, as spaces (the kind of space each amino acid occupies - it's topological relations with the elements in its vicinity - matters to the final protein form), or even rather as a verb: not 'space' as an abstract noun but spac-ing as a verb, as something that happens, the 'event' of spacing in the folding of the protein as carrier of information. The same can be said of time, which I why I similarly speak of 'timing' rather than Time in the substantive (a large deal of the confusion over space and time is grammatical, I suspect).

The basic idea is to get rid of conceptions of space and time which treat either as a kind of mere 'container' in which things happen, but which are themselves not part of 'what happens', as it were. It's to insist on the irreducible reality of space and time, their tangibility, their affective force - in short, their materiality - as something that cannot be considered apart from what happens: in this case the morphogenesis of the protein. Also, if you remember the Guess book, he also specifically writes of how timing in politics is one of the biggest factors when conducting any political analysis, but that it's so often forgotten in the High Theory of Political Philosophy, which aims, like all idealism, to desanguinate the world of both space and time. -

Dominic Osborn

39Reply to the OP:

Dominic Osborn

39Reply to the OP:

For an ontological idealist (not a Kantian): not only is Space ideal, but substance/bodies/atoms/matter are too. So Space isn’t any less forceful, material, real, significant, etc. than those things. Not only is Time ideal, but its being a series of events is also ideal. So Time isn’t any less real than the series of events that constitute it.

I would agree with you: Space and Time are as important as their contents or constituents. I’m having a drink right now; it happens to be coffee—but it might have been tea; I wouldn’t have cared much. But I’m pouring it down my throat, not into my ear or my nose: that is important. Whether my parachute is made of silk or some synthetic fibre is unimportant; whether it is strapped to my back before or after I jump off the plane is. It seems to me that you could accord plenty of value to Space and Time even if you weren’t idealist in any way. Space and Time don’t have to be material or forceful in order to be important. Why isn’t the distribution of things and what is distributed of equal value?

Getting to grips with your post really requires getting to grips with what we mean by Space and Time and their contents or constituents.

I think there’s a lot of the whole/parts relationship between Space and what you’re calling material or forceful things—and between Time and what you might (perhaps?) call events. And I think there is an illegitimate bias towards the ontological priority of the parts. People—specially physicalists—think that atoms, or quanta or spatial points, or whatever it is, are ontologically fundamental—and that the wholes that result from their combination are illusory, or at most secondary. You start off with one, then you add one, then you get what they equal. I think you can just as easily go the other way. Start off with the whole and then divide it up. Think of creation myths.

Reply to your follow-up:

Isn’t there an echo of the Newton/Leibnitz argument about Space in your talk of spacing? You’re on the Leibnitz side. You think the relationships between material things, how they are configured—is Space. You think the Newtonian view—a fixed vessel, independent of its constituents—is wrong.

And you think those relationships—whether the objects/bodies/atoms/quanta/events are configured this way or that—has causal significance. One configuration would cause X, another (of the same things) would cause Y. Two events in a different order have different causal results (like the parachute example). For that reason you want to say that Space and Time are material and forceful.

I don’t like Kant’s halfway house either. But I’m on the far side of Kant from you.

(But I still enjoyed your posts.) -

Streetlight

9.1kThanks! I don't know about Leibniz though - time and space remained 'well founded phenomenona' for him and as such don't really have any ontological status in his monadism apart from that. I think he was right to relativize both to 'objects' (I'd prefer to say processes) against Newton's (and thus Kant's) absolutization of them, but I think he was wrong to infer that this reletivization merely rendered them 'well-founded phenomena'. Basically, I want to have my cake and eat it too: I want to say that space and time are both relative and real. The 'trick', to the extent that there is one, is to also accord this same status to 'objects' - or again, processes - as well: there is nothing that isn't relative - nothing that isn't context-bound, nothing that doesn't function differentially - that is also real, a part of reality.

Streetlight

9.1kThanks! I don't know about Leibniz though - time and space remained 'well founded phenomenona' for him and as such don't really have any ontological status in his monadism apart from that. I think he was right to relativize both to 'objects' (I'd prefer to say processes) against Newton's (and thus Kant's) absolutization of them, but I think he was wrong to infer that this reletivization merely rendered them 'well-founded phenomena'. Basically, I want to have my cake and eat it too: I want to say that space and time are both relative and real. The 'trick', to the extent that there is one, is to also accord this same status to 'objects' - or again, processes - as well: there is nothing that isn't relative - nothing that isn't context-bound, nothing that doesn't function differentially - that is also real, a part of reality.

In the case of the spatio-temporal regulation of protein folding for instance, while the exact mechanisms are still being worked out, the dynamics have to do, ultimately, with physical forces acting on the amino acids - forces like energy and chemical differentials/gradients, hydrophobic and electrostatic forces, binding and bending energies, as well as ambient conditions like pH, temperature and ion concentration. As Peter Hoffmann puts it, "a large part of the necessary information to form a protein is not contained in DNA, but rather in the physical laws governing charges, thermodynamics, and mechanics. And finally, randomness is needed to allow the amino acid chain to search the space of possible shapes and to find its optimal shape." - The 'space of possible shapes' that Hoffmann refers to is the so-called 'energy landscape' that a protein explores while folding into its final shape, where it settles into energy-optimal state after making it's way through a few different possible configurations (different configurations 'cost' different amounts of energy, and cells regulate things so that the desired protein form settles into the 'right' energy state). (Quote from Hoffmann's Life's Ratchet).

Anyway, the point of that mini-lesson in protein folding is that while the spatio-temporal dynamics of the foldings are themselves regulated by all these different mechanisms (that is, while spacing and timing are still relative to the biodynamics), those dynamics nonetheless exert real effects of their own. If the timing is not right, a protein will misfold, and you'll end up with Parkinson's or Alzheimer's. The same with the specific spatial topologies. The whole processes is a 'holistic' one, working in concert, where each process - of which spatialization and temporalization are two among others - is as vital to the result as every other. There is a reciprocity of condition and conditioning. This is why I absolutely deny that anything in particular is ontologically fundamental, as it were. In fact, this entire thread was motivated by some thoughts in my last thread in which the entire point was to argue against the idea that any 'level' of reality would be more fundamental than any other (here, if you want the context).

Note also that by Idealism I don't mean anti-realism, but more properly Idealism in the Platonic sense, where one Idealized strata of reality is taken to contain, on it's own, the governing principles of the rest of the universe (Forms or εἶδος - or, in their modern day guises, 'atoms' and 'fundamental particles'). -

Maw

2.8kVery insightful post, and one (if I am understanding correctly) egregious example of the application of chrono-politics that immediately comes to mind, to me, is how members of the Republican Party and the NRA, promptly attempt to depoliticize the nature of a mass shooting, "killing time", by suggesting that "now is not the time for politics", and stretching the time in which it will be appropriate to discuss political solutions to a undisclosed future in which the urgency and the emotion will have dissipated.

Maw

2.8kVery insightful post, and one (if I am understanding correctly) egregious example of the application of chrono-politics that immediately comes to mind, to me, is how members of the Republican Party and the NRA, promptly attempt to depoliticize the nature of a mass shooting, "killing time", by suggesting that "now is not the time for politics", and stretching the time in which it will be appropriate to discuss political solutions to a undisclosed future in which the urgency and the emotion will have dissipated. -

apokrisis

7.8kThe philosophical relevance of this is that, when it comes to protein folding, space and time carry information, or rather, spacing and timing, specific geometries and specific timings have effects that cannot be 'read off' primary structure alone. Another way to put this is that spacing and timing are material: they are not idealized 'forms', but forces in their own regard, worldly 'contents'. — StreetlightX

apokrisis

7.8kThe philosophical relevance of this is that, when it comes to protein folding, space and time carry information, or rather, spacing and timing, specific geometries and specific timings have effects that cannot be 'read off' primary structure alone. Another way to put this is that spacing and timing are material: they are not idealized 'forms', but forces in their own regard, worldly 'contents'. — StreetlightX

So this is arguing a constraints-based or pan-semiotic view. But it wants to reject the reality of forms and talk about the reality of materiality.

I would instead argue for the complementarity of the two. A systems approach would see each as equally real in their own way. And progress would be making that explicit in the scientific modelling of the situation.

This was of course exactly what Pattee (Rosen's colleague) did with his epistemic cut approach to protein folding in particular. It is why the kind of biophysics described by Hoffman is so significant. We can see how life is the semiotic combo of information and dynamics, or formal cause and material cause. With a new understanding of the biophysics of the quasi-classical nanoscale, we can even see how biological information arises because the differences between kinds of material entropies disappears. Materiality can be regulated because it cost essentially nothing to switch it from one track to the other. Materiality becomes programmable.

And this is a fact about spatio-temporality. It is due to there being a symmetry-breaking transition between a quantum state of materiality and a classical one at a certain distance and energy scale.

So Kant is a bit irrelevant. He was only thinking of the classical conception of materiality that seems necessary - as an informational constraint - to make the world appear comprehensible to the senses. And that was an essentially "dead" framework. It reflected the Newtonian view of time and space as a backdrop a-causal frame.

We already know from quantum theory that even spacetime is "lively" - observer-dependent in some important fashion. And this essentially informational view is being cashed out through holography and dissipative structure theory. The backdrop is causally involved in its own creation. Physics is arriving at the pan-semiotic view argued by Peirce.

So yes. Information is alive and active everywhere in the Universe. But at the same time, the Universe has a hierarchical organisation of constraints. You can't just simply reject a global backdrop view and replace it by some story of absolute local contingency. A bricolage. That is leaping from one extreme to the other.

The pan-semiotic approach, the holographic approach, the hierarchy theory approach, the infodynamic approach, are all ways of saying the same thing. Reality is an emergent equilibrium balance of its own internally opposed tendencies. It is formed by its dichotomous actions - in particular, the tension between global integration and local differentiation.

So a globalised view - one that sees space and time as a dispassionate or a-causal container - is not the sole story. But nor will any completely local and contingent view - one that invokes an infinite variety of particular individuated causes - be either.

The art of telling the story of existence lies in seeing how at every scale of being it is expressing the balancing of its formative tensions.

And that too is a metaphysics with its political implications of course. :) -

Streetlight

9.1kThat's actually a really interesting example because it allows me to make a distinction I hadn't thought of before: chronopolitics as tactic and chronopolitics as end. To explain: I think the refrain that 'now is not the time for politics' is indeed a political uptake of time (it's a contest over time, it's use, it's meaning - a time for mourning or a time for activism? Both? Neither?), but its more an means to an end than an end itself. What I had in mind was instead chronopolitics as end - the fight for a 5 day workweek and an 8 hour workday was not so much tactical as it was an end in itself: the contest over time just is the point of that political fight.

Streetlight

9.1kThat's actually a really interesting example because it allows me to make a distinction I hadn't thought of before: chronopolitics as tactic and chronopolitics as end. To explain: I think the refrain that 'now is not the time for politics' is indeed a political uptake of time (it's a contest over time, it's use, it's meaning - a time for mourning or a time for activism? Both? Neither?), but its more an means to an end than an end itself. What I had in mind was instead chronopolitics as end - the fight for a 5 day workweek and an 8 hour workday was not so much tactical as it was an end in itself: the contest over time just is the point of that political fight.

Another example which imbricates the two (space and time, tactics and end) might be the fight - particularly relavent in Australia, or Sydney rather (and San Fransisco now I think about it) - over affordable housing. The fight for affordable housing is more than an economic one: it is also a fight over differential access to 'life resources' - work, public transport, retail outlets and spaces for socialization. It may cost less to live far away from the/an urban centre, but one pays the price in both space and time, literally. Those that can afford housing close to life resources are richer not only in monetary terms, but spatial and temporal ones too. So just by thinking in terms of space and time, you actually get to tie in a whole range of other considerations too: demography, geography, economics, and public policy, to name a few.*

And this should make sense at the philosophical level: again, Kant was right to call space and time conditions of experience, but that they are conditions of all experience also means that everything has an irreducible temporal and spatial dimension that can be taken into account. To think in terms of space and time inevitibly means to think also in terms other than just space and time.

*An additional thought: in the US - although not only in the US - such considerations are also massively bound up with questions of race, insofar as the legacy of redlining - 30 years of racial neighbourhood segregation - has effects that still play themselves out today, effects that I think were perhaps even more consequential - although far less talked about - than school or other institutional segregation. -

Streetlight

9.1kLefebvre's The Production of Space is one of my favourite books ever, and the work of Doreen Massey (Space, Place and Gender) was transformative in my understanding of how space is infused with power, and hence, a site of political contestation. One of the things I'm trying to do in the OP is, at it were, sneak these perspectives in through the backdoor with a case study from the sciences, and poke at Kant in the process, which is why I briefly mentioned the role of political geography in the OP - I actually had Harvey in mind here, although you're right that I probably should have spoken about human geography instead. To the idea of chronopolitics one could perhaps add the notion of a cartopolitics...

Streetlight

9.1kLefebvre's The Production of Space is one of my favourite books ever, and the work of Doreen Massey (Space, Place and Gender) was transformative in my understanding of how space is infused with power, and hence, a site of political contestation. One of the things I'm trying to do in the OP is, at it were, sneak these perspectives in through the backdoor with a case study from the sciences, and poke at Kant in the process, which is why I briefly mentioned the role of political geography in the OP - I actually had Harvey in mind here, although you're right that I probably should have spoken about human geography instead. To the idea of chronopolitics one could perhaps add the notion of a cartopolitics... -

Maw

2.8k*An additional thought: in the US - although not only in the US - such considerations are also massively bound up with questions of race, insofar as the legacy of redlining - 30 years of racial neighbourhood segregation - has effects that still play themselves out today, effects that I think were perhaps even more consequential - although far less talked about - than school or other institutional segregation. So just by thinking in terms of space and time, you actually get to tie in a whole range of other considerations too: demography, geography, economics, and public policy, to name a few.* — StreetlightX

Maw

2.8k*An additional thought: in the US - although not only in the US - such considerations are also massively bound up with questions of race, insofar as the legacy of redlining - 30 years of racial neighbourhood segregation - has effects that still play themselves out today, effects that I think were perhaps even more consequential - although far less talked about - than school or other institutional segregation. So just by thinking in terms of space and time, you actually get to tie in a whole range of other considerations too: demography, geography, economics, and public policy, to name a few.* — StreetlightX

Exactly. Black-Americans have largely been excluded from - not merely the idyllic concept of the "American Dream", but, more substantively, the real phenomenon of upwards social mobility, inherited transfer of wealth, education opportunities, etc., due to a vast collection of racist policies and politics stretching from slavery, Jim Crow laws, redlining, the War on Drugs, and a nearly endless stream of racially motivated forms of exclusionary practices. Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote a famous article, also for The Atlantic in 2014 on "The Case For Reparations", arguing that, White America owes a "moral" and literal debt to Black Americans due to "two hundred fifty years of slavery. Ninety years of Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate but equal. Thirty-five years of racist housing policy," that effectively rendered Black Americans literally segregated from opportunities available to other general Americans. -

Maw

2.8kAlso, just had a curious thought relating this idea of chronopoltics to the "X" History Month, where X is a historically/currently excluded minority (e.g. Gays/Blacks/Women), in which our collective society recognize this community and prominent individuals within the it, and celebrate them in ways that range from meaningful to cheap Capitalist cash-grabs, but ultimately relegate the importance and dignity of such communities to merely one month out of the year, like some annual ritual where, for a paltry 30 days (28 for Black America), we celebrate the contributions of certain communities, then return to "normal". No doubt this is not a novel idea in-itself, but I think it does play into the concept of chronopoltics.

Maw

2.8kAlso, just had a curious thought relating this idea of chronopoltics to the "X" History Month, where X is a historically/currently excluded minority (e.g. Gays/Blacks/Women), in which our collective society recognize this community and prominent individuals within the it, and celebrate them in ways that range from meaningful to cheap Capitalist cash-grabs, but ultimately relegate the importance and dignity of such communities to merely one month out of the year, like some annual ritual where, for a paltry 30 days (28 for Black America), we celebrate the contributions of certain communities, then return to "normal". No doubt this is not a novel idea in-itself, but I think it does play into the concept of chronopoltics. -

Streetlight

9.1kAlso, just had a curious thought relating this idea of chronopoltics to the "X" History Month, where X is a historically/currently excluded minority (e.g. Gays/Blacks/Women), in which our collective society recognize this community and prominent individuals within the it, and celebrate them in ways that range from meaningful to cheap Capitalist cash-grabs, but ultimately relegate the importance and dignity of such communities to merely one month out of the year, like some annual ritual where, for a paltry 30 days (28 for Black America), we celebrate the contributions of certain communities, then return to "normal". No doubt this is not a novel idea in-itself, but I think it does play into the concept of chronopoltics. — Maw

Streetlight

9.1kAlso, just had a curious thought relating this idea of chronopoltics to the "X" History Month, where X is a historically/currently excluded minority (e.g. Gays/Blacks/Women), in which our collective society recognize this community and prominent individuals within the it, and celebrate them in ways that range from meaningful to cheap Capitalist cash-grabs, but ultimately relegate the importance and dignity of such communities to merely one month out of the year, like some annual ritual where, for a paltry 30 days (28 for Black America), we celebrate the contributions of certain communities, then return to "normal". No doubt this is not a novel idea in-itself, but I think it does play into the concept of chronopoltics. — Maw

This is perhaps a worthy debate topic of it's own, but the distastefulness - If I can call it that - of having something like a Black History Month or a Gay Mardi Gras is, I think, part of the point. It's probably true that we shouldn't need to have an X history month of whathaveyou, but, if I may put it paradoxically, the fact that we shouldn't need to have it is all the more reason to have it. But yes, the larger point is that paying attention to the politics of time (and space) allows one to see, or rather, be more sensitive to factors that may not otherwise come to one's attention in explaining particular disparities or differentials in power and/or access to resources.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum