-

The relationship of ideas to languageTrue, true. I guess I'm employing a different sense of recursion, not in the sense of nesting (qua linguistics), but rather 'self-reference' (although I tend to avoid talking about self-reference because of it's association with paradox). While qualifying nested clauses does allow one to expand what one can 'do' with language, I think negation takes it even further to the degree that it allows us to speak of the purely imaginary or what is not present at hand (Tolkein's world, say), whereas recursion qua nesting always needs to begin with a present and then qualify from there. I hope that makes sense.

-

The relationship of ideas to languageI think you're right to focus on what you call 'the idea of never', and what I generally prefer to call 'negation': it's negation, the ability to designate a "not-x", that allows language to become representative and abstract. It allows this because negation is what allows language to refer to itself (it introduces recursion into language) insofar as to say 'not-x' is to refer to one's use of language, rather than some positively existing entity.

Negation (and with it recursion), in turn allows language to separate into 'levels': 'object-language' and 'meta-language', where the 'meta-level' talks about things in the 'object level' (via a 'not': "I am not talking about that"). And once this starts, you can stratify 'levels' pretty much infinitely, so you get meta-meta levels of language and so on - in a word, abstraction (although we can generally handle only so many layers of abstraction, cognitively speaking). In the study of semiotics, negation basically marks the distinction between what is called either the 'icon' or the 'index' on the one hand, and the 'symbol' on the other (where only symbols employ negation, strictly speaking).

As far as ideas go, the more one can take advantage of this ability to abstract (to build level upon level, along complex with 'rules' about how 'higher levels' apply to the 'lower levels'), the more abstract, complex, and generally powerful one's ideas can become. The question then turns upon exactly how 'exclusive' the function of negation is to language. That is, is language powerful because it has 'exclusive rights' to negation, or can and does negation find expression outside of language?

Given that organic systems are known employ 'negation' in their function (nerve axons, DNA helixes), it's probably fair to say that negation is not exclusive to language, and that it just so happens that language (due to the minimal energy expenditures needed to employ it) is very well suited to take advantage of negation. So while ideas cannot be said to be wholly linguistic in nature, language does allow a kind of fantastic acceleration of idea formation - especially complex, multiply recursive ideas. -

Reading Group: Derrida's Voice and PhenomenonHeh, I dunno about 'super dumb', but the significance of the first three or so pages are kinda lost on me. I'm not sure what the discussion of practise and theory is meant, precisely, to establish. Still, once you get past it, the stuff on the voice is wonderful, IMO. Also I see now that I was anticipating quite a bit when I dragged in the discussions of flow and space, which are probably far more appropriate for this chapter than any others. I'm excitable, what can I say.

Also, this is like one of my favourite places to point to, to anyone who says that Derrida is an idealist in any kind of straightforward manner. It baffles me that for years and years Derrida was considered so by so many of his detractors. This was one of my first Derrida reading experiences, and I remember just being taken aback by how flat out wrong were so many of the characterisations of his work that seemed to have passed around. It was probably Searle's fault.

On yet another unrelated note, ever since reading Henry's Material Phenomenology, I've always thought it would be a fascinating exercise to read this along with it. They're both dealing with almost identical material, but they move in diametrically opposite directions: where Derrida more or less tries to problemetize auto-affection, Henry absolutely embraces it; where Derrida places his emphasis on the sign, Henry places it on affection. It's an incredibly fascinating parallel with no point of convergence. -

The 'Postmoderns'Let's look at another example of a subject, Ghandi, someone who was content with his food bowl and the ability to weave his own loin cloth. He lived far more freedom than Trump does, by the freedoms expressed from his mind and enjoying a few genuine friendships and a humble constructive role within his society.

Ghandi exercised his intellect and sculpted, crafted his own mind and psychological life with freedom of imagination and creative intellectual vision. Such freedom emerges in the mind of a subject who is somehow transcendent of their social conditioning. — Punshhh

Yes, Ghandi is another exemplar of the subject of freedom par excellence; Ghandi, who unlike any other two bit hermit who could starve himself for ideals, actually walked down to the sea to break the salt laws in an act of civil disobedience; Ghandi, who refused to move from the first-class carriage in South Africa when asked to do so in defiance of law; Ghandi, who actively engaged in hard fought political negotiations with South African, Indian and British governments, with tangible, society-changing results; Ghandi, who used his considerable charismatic and organizational skills to leads massive protests by his countrymen; Ghandi, who all too readily gave up his liberty, time and time again, for the sake of non-violence; Ghandi, who lead, with incredible political acumen, the Indian National Congress party (and Ghandi, who slept naked with little girls to test his commitment to chastity...; and Ghandi, who considered blacks in Africa savages, and for whom the 'white race' ought to predominate in South Africa; and Ghandi, whose attitude toward the caste system remains an inextinguishable black mark against his legacy).

But by all means, romanticise his 'food bowl' and his 'loin cloth', along with his 'psychological life' and 'freedom expressed in the mind'. By all means, recall everything about him that resides on the low, rusty rungs of his actual practices of freedom. Perhaps this rosy, spiritualist, beautiful-soul swill is why Zizek polemically issued the reminder that Ghandi was far more violent than Hitler, with respect to his cutting against the grain of his time (that is, unlike Hitler, who capitalized upon - and horrifyingly radicalized - the murderous currents already at work in the Europe of his time). There's probably something to be said too about Walter Benjamin's (a 'post-modernist' avant la lettre) thesis that the aestheticization of politics - no doubt commensurate with a vapid and bathetic concern with foodbowls and loincloths - is the logical outcome of fascist ideologizing, but that's probably neither here nor there. -

The 'Postmoderns'Lol. You're protesting that we should the think of the Civil Rights Movement in terms of physics. — Mongrel

Lol. You think this.

Nobody thinks she wanted that particular seat. Her action was highly symbolic. — Mongrel

Sure - symbolic with respect to what? Her historical circumstances? The way the black community was being treated, both in terms of 'lived actions', and codified at the level of law? Nah, must be all that spirit stuff, the stuff that really matters. Authenticity and all that. Heidegger the Nazi knew all about that. Maybe Parks should have just meditated her way to freedom, had a real feeling, intuition, experience of it. She could have just 'thought' her way there. -

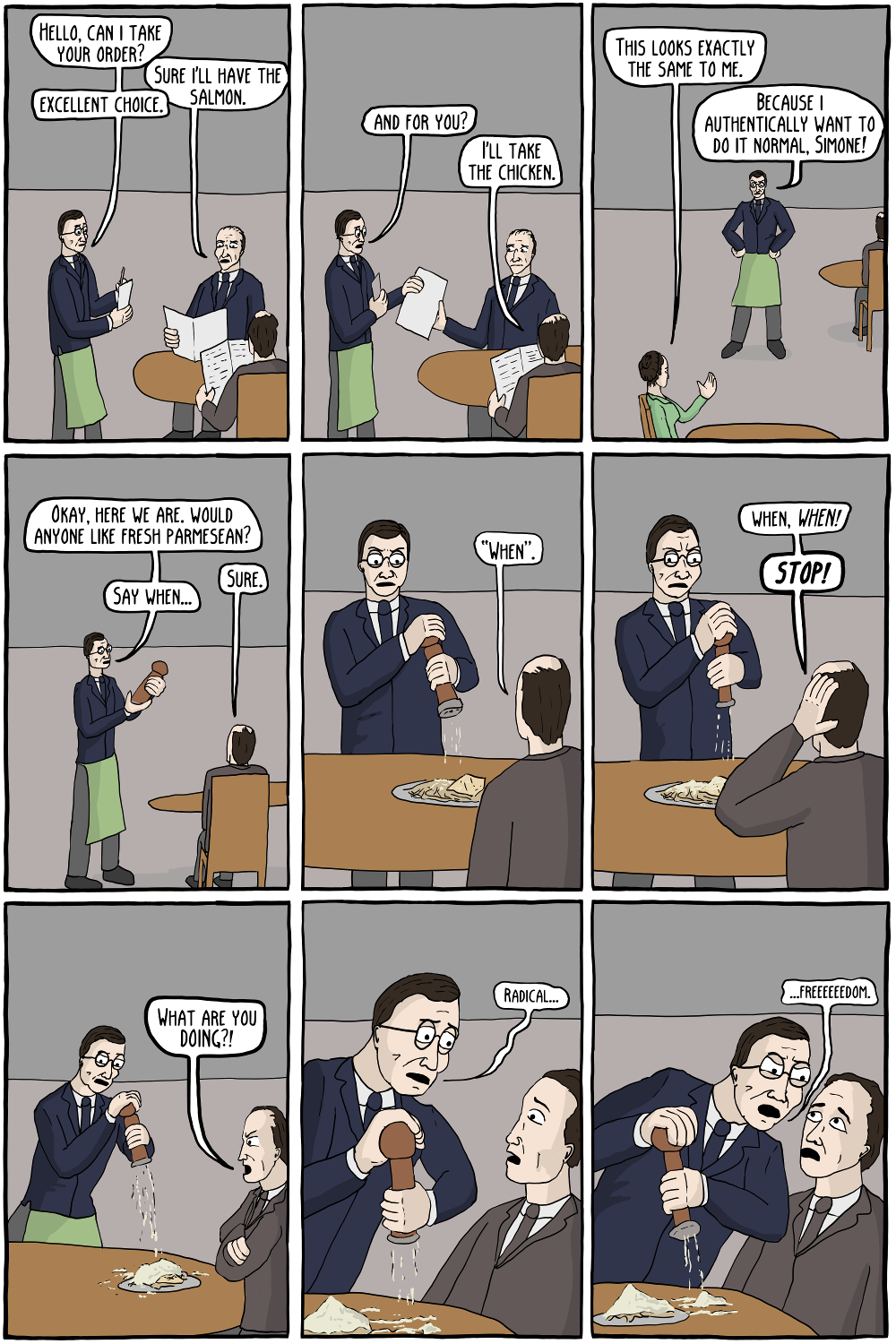

The 'Postmoderns'Also I have to admit, I can't really read the words 'radical freedom' without giggling a little, no thanks to these which were doing the rounds a while back:

-

The 'Postmoderns'What in the world is 'spirit'? It is another completely underdetermined and fuzzy feel good word? As if Parks were not driven by the real, material circumstances in which her community were being treated as second class citizens, as if she wasn't contesting - in a literal manner - the appropriation of space and time (a bus seat, in this case), as if she wasn't responding to the incapacities which defined her societal position. But no, far better, apparently, to think of her acts in terms of 'spirit' and 'authenticity' and 'belief'; psychological weasel words that absolve you of actually engaging in 'life as actually lived', with history, with space and time.

It is interesting, though, how a discussion that started off about the existence of common themes in PM has zeroed in on the issue of freedom. — John

It's not that surprising. After all, you - and not just you, to be fair - have literally had nothing of interest or of substance to say about this thing you call post-modernism to begin with. -

The 'Postmoderns'so how can it not be a matter concerned entirely with our thoughts, beliefs, intuitions and experience, in other words with life as lived ? — John

Because to think 'live is lived' is exhausted by our 'thoughts, beliefs, intuitions and experience' is to conceive of life in a horrifyingly narrow and morbidly 'intellectualist' manner. Rather than live life in ones head, life generally is concerned with the things I do, the things I say, the actions I take. And perhaps even more importantly, the things done to me, said of me, that impel me and make claims upon me; life as composed of habits, regularities, flourishes of creative engagement amongst rhythms of time and movement, punctuated with time wasting, routine, imposition, sleep, intensity, and so on. You seem to have a very weird disembodied, intellectualist notion of freedom that 'lives' entirely in one's head. It's frankly unrecognisable as anything anything to do with freedom, as classically understood. Your notion of freedom seems to turn upon some ineffable experience of warm, fuzzy feelings, the 'inner convictions' of romantic 'radical freedom'.

But freedom for the most part is not this; freedom has a decided aspect of sheer debilitation, incapacity to act in the face of a loss of 'normal' function, a sense of powerlessness that says that 'I can do nothing else but this one thing'; When a Rosa Park sits at the front of a bus, this expression of freedom is abyssal, terrifying, completely dehumanizing in every sense of the word. But it has nothing to do with how she 'feels or thinks' and everything to do with what she does. At it's limit, freedom rubs our subjectivity raw, eviscerates us, erases our particularities precisely by putting us in touch with a universal that is brutally indifferent to the quirks of our psychology and the idiosyncracises of our feelings.

Your mystical sense of 'freedom' seems on the other hand oddly suited to a modern world where, it just becomes another in a long line of inconsequential 'I really, authentically feel it, deep down in my heart of hearts and warm fuzziness!'. A kind of freedom suited for suburban moms who attend yoga class for their dose of 'authentic spirituality' ("belief will set you free, girls!"). But this seems a caricature of the ground-swallowing, incapacitation that freedom, when it presents itself in our acts, can in fact present itself as. -

Can "life" have a "meaning"?I've always found it helpful to rephrase the question in terms of significance, rather than meaning - as in, "what is the significance of life?", rather than "what is the meaning of life?". I'm still not sure, of course, without a proper understanding of what is meant by 'life', that one can yet make sense of the question. But I think casting it in terms of significance helps to refine it a little.

-

The 'Postmoderns'Yeah, tell that to a black lives matter activist or a child laborer. Seriously, does this not strike you as a frankly embarrassing line of questioning?

-

The 'Postmoderns'I have no idea what you're talking about. The subjugated don't give two hoots about abstract nonsense regarding appearance and the "true world" or whatever.

-

The 'Postmoderns'Yeah, I don't much care for dreamed up freedom. A slave in chains remains so regardless of whatever state of 'consciousness' they remain in. Lucid dreaming and 'inner experience' are just so much mystical salad dressing that have nothing to do with the concrete exercise of freedom. It's crystal healing disguised as medicine.

-

The 'Postmoderns'So freedom cannot ever be an "abstract truth" but rather something that must first be believed (on the basis of our intuitions and lived experience) before it can be fully lived. — John

But what in the world has belief got to do with freedom? A belief in unicorns speaks nothing as to their reality, and I don't see what a 'belief' in freedom has to do with the practice and exercise of freedom either. In any case, without specifying how belief functions to guarantee freedom - and yes, as Willow points out, you're leveraging belief as a guarantee for freedom, no matter your protestations to the contrary - all you're doing is displacing the problem. To be free, one must believe: OK but what is belief other than some kind of immaterial, 'mental' conviction, no different to one's 'belief' in UFOs and The Secret? In fact, how does your position differ from the self-help woo that is The Secret at all? -

The 'Postmoderns'You mistake me. When I speak about 'guarantees', I mean precisely statements like this:

The one universal thing about selves is the fact that they are all truly free. — John

I mean, if you really believe this, then all you bluster about freedom needing to be lived, intuited, etc is meaningless. If we're so 'radically free', then what need any practise of freedom? This whole trope about spirit and freedom is on par with animism for me, it treats freedom as this abstract truth which zero bearing on life as actually lived. When I speak about guarantees, I'm speaking out against any such notion, especially any mythical notion of freedom as spirituality ingrained or whatever mystical thesis that makes of freedom some reified Idea in the sky or soul or whatever.

Foucault in fact has a wonderful quote about this, especially on the notion of 'guarantees': "Freedom is practice; . . . the freedom of men is never assured by the laws and the institutions that are intended to guarantee them. That is why almost all of these laws and institutions are quite capable of being turned around. Not because they are ambiguous, but simply because ‘freedom’ is what must be exercised . . . I think it can never be inherent in the structure of things to (itself) guarantee the exercise of freedom. The guarantee of freedom is freedom”. -

The 'Postmoderns'A case can be made that if there is something universal about human nature, then we don't have the radical freedom, ethical responsibility etc that you seem to want to preserve. If there is an essence and that essence is given by something outside the subject (by something transcendent, say), where is the freedom? — Πετροκότσυφας

Incidentally, this line of reasoning is more or less exactly what drew me towards these kinds of thinkers; the notion of human freedom as guaranteed by some liberal conception of universality always struck me as cartoonish and ridiculous, and it always seemed to me that it'd only be by working through the processes of subjectivization that one could ever, in any coherent manner, speak about freedom. -

The 'Postmoderns'I agree though - I just meant that Foucault, far more than Deleuze or Derrida, was a theorist of subjectivization, it's modes of operation, etc, etc. In fact it was in grappling with the work of late Foucault that I actually turned to - of all people - Zizek, or psychoanalysis more generally, which seemed to offer a way out of what seemed to me to be the impasses in Foucault's thoughts on freedom. Without getting into it too much, while late Foucault began to look into the techniques of the self as a means for subjective refashioning and so on, I've never been convinced he adequately theorized the mechanisms for those techniques he wants to say that man is capable of (in Lacanian terminology, Foucault has no conception of the Real)*. But that's a more narrow, theoretical issue.

--

*Giorgio Agamben gives voice to what I mean when he writes, in the famous opening lines of his Homo Sacer: "In his final years Foucault seemed to orient this analysis according to two distinct directives for research: on the one hand, the study of the political techniques (such as the science of the police) with which the State assumes and integrates the care of the natural life of individuals into its very center; on he other hand, the examination of the technologies of the self by which processes of subjectivization bring the individual to bind himself to his own identity and consciousness and, at he same time, to an external power. Clearly these two lines (which carry on two tendencies present in Foucault's work from the very beginning) intersect in many points and refer back to a common center.

...Yet the point at which these two faces of power converge remains strangely unclear in Foucault's work, so much so that it has even been claimed that Foucault would have consistently refused to elaborate a unitary theory of power. If Foucault contests the traditional approach to the problem of power, which is exclusively based on juridical models ("What legitimates power?") or on institutional models ("What is the State?"), and if he calls for a liberation from the theoretical privilege of sovereignty" in order to construct an analytic of power that would not take law as its model and code, then where, in the body of power, is the zone of indistinction (or, at least, the point of intersection) at which techniques of individualization and totalizing procedures converge? And, more generally, is there a unitary center in which the political "double bind" finds its raison d'etre?

...Although the existence of such a line of thinking seems to be logically implicit in Foucault's work, it remains a blind spot to the eye of the researcher, or rather something like a vanishing point that the different perspectival lines of Foucault's inquiry... converge toward without reaching." -

The 'Postmoderns'Perhaps the reason that Foucault, Deleuze and Derrida do not talk about the self in this sense is that for them it simply does not exist. — John

This is manifestly untrue. There's not much else to say about that.

Perhaps, but there is something for the self to be transcendent of and that is really the point of Henry's polemic against any scientific understanding of the "individual". The point for Henry (and interestingly in a similar way for Berdyaev whom I've also been enjoying reading of late) is precisely that the individual is not the self. — John

Eh, the disjunction between the subject and the self (or the 'ego') has a long and rich history, and is pretty pervasive with respect to all the philosophers we're discussing here. I suspect Henry would reel against speaking about any of his philosophy in terms of transcendence, but I'm not very invested in that debate either way. -

The 'Postmoderns'As far as I understand Henry though, he would reject that there's anything for such immanence to be transcendent to in the first place. 'Worldly relations' aren't 'excluded' from his notion of immanence, they just don't exist tout court. There is no 'outer' for an 'inner' to be contrasted against. It's just affect all the way down (and up). Anyway, from phenomenology to post-structuralism I simply see an evolving line, and one of the miserable ramifications of speaking about 'post-modernism' that that it utterly obscures the richness of the connections and the breaks that take place along that line.

As for defining postmodernism in terms of it's take on the 'subject', that seems to me to be a particularly reductive take on this. Although it chimes nicely with Foucault, Derrida and Deleuze hardly talk about the category of the subject at all, and with Deleuze in particular, the subject is simply one among every other product of individuation which applies no less too river, rocks, climates and societies. The idea that 'post-modernism' is overbearingly concerned with questions of subjectivity is one of those pervasive myths that deserves a rather quick and unceremonious death. -

The 'Postmoderns'Hmm, like I said, I'm not super familiar with these lines of thought, and the only work I've read of Henry's is his Material Phenomenology, which requires a pretty decent understanding of Husserlian phenomenology, so I don't think it'll be up your alley. His other books, Words of Christ, I Am the Truth and Incarnation might be of more interest to you (Words of Christ is supposed to be a relatively easy read). I know that Catherine Keller wrote a well received book on negative theology recently (Cloud of the Impossible, but I've not read it myself.

Eugene Thacker has written some very interesting things in the tradition of negative theology, but his is a kind of 'negative atheology' in the line of Georges Bataille. Still his book After Life is easily one of my favorite ever books, as I can't recommended it enough. Daniel Barber Colucciello released an intriguing book not too long ago about reading Deleuzian immanence in a theological key (Deleuze and the Naming of God), but, again I've not read it. Otherwise John Caputo is supposed to be quite easy to read and is a pretty popular theologian in the Derridian vein. -

The 'Postmoderns'I should note that there is a rich tradition of theological thought among those authors considered 'post-modern' as well (another reason why the label is so reductively stupid): Jean-Luc Marion and Levinas being the 'big names', not to mention John Caputo, a reader of Derrida who thoroughly theologizes deconstruction. And there's also Michel Henry, who, in some sense holds to a thesis of immanence even more radical than Deleuze's, and who thoroughly understands it according to the Christian tradition. I do very little reading in this area, so I dont really mention them much, but the veins of this line of thought run very deep indeed.

-

Reading Group: Derrida's Voice and PhenomenonBut if you use Husserl's work to collapse the distinction ..... then you've created a weird loop where you're trying to undermine the thing you rely on to produce that undermining, which therefore can't be undermined, lest it no longer serve as a way to undermine itself - this isn't even circularity, I don't know what you would call it. — csalisbury

I think you'd call it deconstruction :D Anyway, perhaps the trouble is that Derrida doesn't 'simply' collapse the distinction. Part of what's at stake is the refusal of a simple either/or: either pure presence of a single term or sheer distinction between two, which will amount to the same thing for Derrida. Rather Derrida wants what he calls differance (or 'trace') to inhabit the space in-between both, a kind of both/and operation uses the tension between expression and indication, presence and non-presence, as a kind of springborad or propellant which cannot be stilled by settling upon one term or the other.

Speaking broadly, this has to do with Derrida's unwavering commitment to the transcendental, and his refusal to simply cede transcendental thinking to the empirical. Peter Dews brings this out very nicely in his essay on Derrida, where he notes that Derrida consistently defends Husserl against those who would, in fact, simply collapse the transcendental into the empirical: "Derrida vigorously denies that the 'methodological fecundity' of the concepts of structure and genesis in the natural and human sciences would entitle us to dispense with the question of the foundations of objectivity posed by Husserl. He staunchly defends the priority of phenomenological over empirical enquiry, arguing that, 'The most naive employment of the notion of genesis, and above all the notion of structure, presupposes at least a rigorous delimitation of prior regions, and this elucidation of the meaning of each regional structure can only be based on a phenomenological critique. The latter is always first by right...'.

A similar attitude is expressed in Derrida's article of 1963 on Levinas, 'Violence and Metaphysics', where he argues, against Levi-Strauss, that the 'connaturality of discourse and violence' is not to be empirically demonstrated, that 'here historical or ethnosociological information can only confirm or support, by way of example, the eidetic-transcendental evidence'. Furthermore, this parrying of what is seen as a self-contradictory relativism is also central to Derrida's review of Madness and Civilization, and hence to the highly symptomatic contrast between Foucauldian and Derridean modes of analysis. For what Derrida objects to in Foucault is the attempt to define the meaning of the Cartesian cogito in terms of a determinate historical structure, the failure to grasp that the cogito has a transcendental status, as the 'zero point where determinate meaning and non-meaning join in their common origin'" (Dews, Logics of Disintegration)

So I think @Moliere is exactly right to say that Derrida isn't out to 'disprove' Husserl so much as to 'inhabit' his thought. Even in the first chapter Derrida will speak of how "the whole analysis will move forward therefore in this hiatus between fact and right, existence and essence, reality and the intentional function"; and further of "this hiatus, which defines the very space of phenomenology....". It is in this 'hiatus' which Derrida will seek to remain in, without identifying with either term on either side of it.

--

Re: Land, I think that's the general consensus. I've only read the Bataille book as well (it's where the quote comes from, and in truth, it's perhaps the only passage in the whole book that I recall well), and like you said, there's a hyper-intelligence tinged with madness that both terrifying and spectacular at the same time. I only ever see his name now mentioned as one of the pre-cursors to the 'alt-right' movement, which both surprises me and doesn't, but I haven't really followed up on that. Curiously, I noticed he was running an online seminar with the Sydney School of Continental Philosophy just a few months ago, so it seems at least that he hasn't entirely abandoned institutional philosophy. -

Reading Group: Derrida's Voice and PhenomenonI don't understand what you mean. The perception does not 'turn into' representation at its far end. Representation is going to be things like secondary memory and fantasy, which are not a function of this shading off, but have to be introduced by separate noetic acts (primary memory does not 'become' secondary memory at its far end, and fantasy has to be deliberately introduced by new acts of imagination). — The Great Whatever

Sorry, I mean to refer to the 'structure of representation' qua the possibility of repetition. Hence the losing remarks of the chapter: "Without reducing the abyss that can in fact separate retention from re-presentation .... we must be able to say a priori that their common root, the possibility of re-petition in its most general form .... is a possibility that not only must inhabit the pure actuality of the now, but also must constitute it by means of the very movement of the différance that the possibility inserts into the pure actuality of the now."

As for Hagglund, you miss the point. Hagglund doesn't simply express incredulity, but notes the instances according to which, "whenever Husserl sets out to describe the pretemporal level, he will inevitably have recourse to a temporal vocabulary that questions the presupposed presence."

The point of demonstrating that the indication/expression distinction cannot hold is to then show how the failure of that distinction compromises the rest of Husserl's project. But if the rest of Husserl's project is precisely what you need to collapse that distinction.... — csalisbury

Yeah, this is a very contentious point of Derrida's philosophy as a whole. He always avows his commitment to the metaphysical tradition, claiming never to be able to quite 'exit' it. There are really two ways to take this. On the one hand, you get an incredibly hostile and foreful reading like the one Nick Land offers, where he accuses Derrida of more or less being a supreme apologist of metaphysical thought:

"Deconstruction is the systematic closure of the negative within its logico-structural sense. All uses, references, connotations of the negative are referred back to a bilateral opposition as if to an inescapable destination, so that every ‘de-’, ‘un-’, ‘dis-’, or ‘and-’ is speculatively imprisoned within the mirror space of the concept. ... Such logicization of the negative leads to Derrida ‘thinking’ loss as irreducible suspension, delay, or differance, in which decision is paralysed between the postponement of an identity and its replacement. Suspension does not resolve itself into annihilation, but only into a trace or remnant that has always been distanced from plenitude (rather than deriving from it), so that differance is only loss in the (non)sense of irreparable expenditure insofar as this can be described as the insistence of an unapproachable possibility, which is to say, under the aegis of a fundamental domestication.

...[In Derrida], the ‘text of Western metaphysics’ finds itself subject to a general ‘destruction’, ‘deconstruction’, or restorative critique, which—amongst other things—fabricates ‘it’ into a totality, rescues it from its own decrepit self-legitimations, generalizes its effects across other texts, reinforces its institutional reproduction, solidifies its monopolistic relation to truth, confirms all but the most preposterous narratives of its teleological dignity, nourishes its hierophantic power of intimidation, smothers its real enemies beneath a blizzard of pseudo-irritations (its ‘unsaid’ or ‘margins’), keeps its political prisoners locked up, repeats its lobotomizing stylistic traits and sociological complacency, and, in the end, begins to mutter once more about an unnamable God. Deconstruction is like capital; managed and reluctant change." (Land, The Thirst for Annihilation)

On the other hand, champions of Derrida will say that Derrida allows for the de-sedimentation and destablization of fixed identities and differences, allowing for ethical openings etc, etc. There's an element of truth in both I think, although I am more sympathetic than not. -

TPF Quote Cabinet"As to what [philosophers] meant by continuity and discreteness, they preserved a discreet and continuous silence..."

- Bertrand Russell

Y'know he was real proud when he came up with this one. -

The 'Postmoderns'You see this is a mistaken quest, the transcendent is the immanent in the eye of the mystic. Wherever one approaches or suspects the transcendent, or the transcendental one is mistaken and yet that same approach and suspicion is to and is of oneself, (oneself needn't have gone out to look in the first place, for the gaol, the aim was already here and know).The mystic squares the circle by realising that his/her mind only sees/knows that which leads/looks away from the immanent, the transcendent is mistakenly thought to be out there and one might see it and know it, or never attain it or understand it. But it and the immanent are one in one, in the self and not in the purview of the mind, but the whole self.

I can understand how this might be problematic in philosophy.

Anyway going back to your question, a notion of self is a mental construct, the self which concerns the mystic is the being in which we have our being, in which we have our mind and it's contents. It is understood that the mind cannot access this being, as the mind only looks out from it. Instead the mind is stilled, bypassed, schooled in receiving inspiration through contemplation and living practice. Methodology for this practice is well documented in various religious and mystical traditions. The goal is to develop a synthesis between body spirit and mind, resulting in the transmutation, or in ocassion transfiguration of the self.

I don't know if this can be parsed philosophically(logically), I would have to ask a philosopher? — Punshhh

I dunno man, this just literally sounds like nonsense to me. Not trying to put you down, but there's no-sense I can make of it. It's just standard woo talk. -

The 'Postmoderns'Web, network, ecology - yeah, those are apt phrases. Immanence doesn't 'stop', the reasons 'keep going', this is the 'vertigo of immanence' that Deleuze refers to with respect to Spinoza. But like you said, this is all very imprecise and florid, and without developing - as Deleuze does - the metaphysics of difference which underpins this, it's hard to be clear about.

-

The 'Postmoderns'They develop it in lots of places, and as I said, the history that I quoted is extremely condensed. Understanding the ideas require a pretty good grasp on that history though, because they aren't static notions, but precisely ones that change depending on their use. One way I like to think about it is in terms of the principle of sufficient reason. For everything there is, there is a reason it is so and not otherwise. Transcendence will answer this question 'vertically' - it will link reason to reason in a rising chain until you reach some sort of primordial source or end-point beyond which one can no longer go (or it will deny the question and just say that some shit just is). Immanence will attempt to answer horizontally - it will disseminate reasons along a horizontal axis which at it's limit point, encompasses everything in the universe, without going beyond it. In scientific terms, one speaks of a universe that self-organizes. But these are rough approximations, and the PoSR is itself a very complex topic unto itself (everyone tends to forget, for example, the rider "and not otherwise", which completely changes the nature of the question).

-

The 'Postmoderns'Do any continental and/or postmodernist etc. philosophers employ transcendence/immanence in a non-religious or non-spiritual way, or are they all referring to religious or spiritual ideas? — Terrapin Station

Nah, it's not an explicitly spiritual idea at all. In phenomenology, for example, transcendence generally refers to a certain structure of subjectivity which is meant to distinguish subject from object. Deleuze and Guattari give a short and extremely condensed history of immanence in What Is Philosophy?, where they track it's evolution from Plato, on down to the Christian philosophers (they mention Nicholas of Cusa, Eckhart, and Bruno), before turning to modern philosophy. The distinction saturates the entirety of the history of philosophy. Anyway, here are some of the later passages:

"Beginning with Descartes, and then with Kant and Husserl, the cogito makes it possible to treat the plane of immanence as a field of consciousness. Immanence is supposed to be immanent to a pure consciousness, to a thinking subject. Kant will call this subject transcendental rather than transcendent, precisely because it is the subject of the field of immanence of all possible experience from which nothing, the external as well as the internal, escapes. Kant objects to any transcendent use of the synthesis, but he ascribes immanence to the subject of the synthesis as new, subjective unity. He may even allow himself the luxury of denouncing transcendent Ideas, so as to make them the "horizon" of the field immanent to the subject. But, in so doing, Kant discovers the modern way of saving transcendence: this is no longer the transcendence of a Something, or of a One higher than everything (contemplation), but that of a Subject to which the field of immanence is only attributed by belonging to a self that necessarily represents such a subject to itself (reflection).

Yet one more step: when immanence becomes immanent "to" a transcendental subjectivity, it is at the heart of its own field that the hallmark or figure of a transcendence must appear as action now referring to another self, to an-other consciousness (communication). This is what happens in Husserl and many of his successors who discover in the Other or in the Flesh, the mole of the transcendent within immanence itself. Husserl conceives of immanence as that of the flux lived by subjectivity. But since all this pure and even untamed lived does not belong completely to the self that represents it to itself, something transcendent is reestablished on the horizon, in the regions of non belonging ... In this modern moment we are no longer satisfied with thinking immanence as immanent to a transcendent; we want to think transcendence within the immanent, and it is from immanence that a breach is expected."

They go on a little to speak about Sartre, before circling back to Spinoza: "Spinoza was the philosopher who knew full well that immanence was only immanent to itself and therefore that it was a plane traversed by movements of the infinite, filled with intensive ordinates. He is therefore the prince of philosophers. Perhaps he is the only philosopher never to have compromised with transcendence and to have hunted it down everywhere. In the last book of the Ethics he produced the movement of the infinite and gave infinite speeds to thought in the third kind of knowledge. ... He discovered that freedom exists only within immanence. He fulfilled philosophy because he satisfied its prephilosophical presupposition. ... Spinoza is the vertigo of immanence from which so many philosophers try in vain to escape." -

Reading Group: Derrida's Voice and PhenomenonI wanna post some snippets of Martin Hagglund's reading in his Radical Atheism, where he comments on and extends Derrida's arguments here in a way that's pretty illuminating. There are things here that the next chapter in VP covers as well, but it'll be useful to even keep in mind when we do get round to that. This'll be long but worth it. Hagglund begins by noting how for Husserl, not only the perceived, but the very act of perception itself is extended in time. He beings by quoting Husserl:

"Now let us exclude transcendent objects and ask how matters stand with respect to the simultaneity of perception and the perceived in the immanent sphere. If we take perception here as the act of reflection in which immanent unities come to be given, then this act presupposes that something is already constituted — and preserved in retention — on which it can look back: in this instance, therefore, the perception follows after what is perceived and is not simultaneous with it."

Hagglund comments: "Husserl’s philosophical vigilance concerning the temporality of perception is exemplary, as is his attentiveness to the unsettling implications of such temporality. If the act of immanent perception also takes time, it cannot be given as an indivisible unity but exhibits a relentless displacement in the interior of the subject, where every phase of consciousness is intended by another phase of consciousness. Husserl, however, tries to evade the threat of an infinite regress by positing the foundational presence on a third level of consciousness, which he distinguishes from the temporality of retention as well as reflection.

Husserl: "But—as we have seen—reflection and retention presuppose the impressional ‘internal consciousness’ of the immanent datum in question in its original constitution; and this consciousness is united concretely with the currently intended primal impressions and is inseparable from them: if we wish to designate ‘internal consciousness’ too as perception then here we truly have strict simultaneity of perception and what is perceived".

This brings Husserl to the notion of the 'pre-reflexive absolute flow'. An 'unchanging dimension of consciousness which always coincides with itself', where perception and the perceived are simulanious. This is the thesis of 'logitudianal' or 'horizontal' itnentionality that TGW brought up above. Hagglund: "Husserl describes it as a “longitudinal intentionality” that is pretemporal, prereflexive, and preobjective. ... [Yet] Neither Husserl nor his followers can explain how such an intentionality could be possible at all. How can I appear to myself without being divided by the structure of reflexivity? And how can the retentional consciousness — which by definition involves a differential relation between phases of the flow — not be temporal? The only answer from Husserl and his followers is that there must be a more fundamental self-awareness than the reflexive one; otherwise, we are faced with an infinite regress where the intending subject in its turn must be intended and thus cannot be given to itself in an unmediated unity."

-- Absolute Flow:

Hagglund now turns to Husserl's description of the absolute flow; Husserl: "The flow of the consciousness that constitutes immanent time not only exists but is so remarkably and yet intelligibly fashioned that a self-appearance of the flow necessarily exists in it, and therefore the flow itself must necessarily be apprehensible in the flowing. The self-appearance of the flow does not require a second flow; on the contrary, it constitutes itself as a phenomenon in itself. The constituting and the constituted coincide, and yet naturally they cannot coincide in every respect. The phases of the flow of consciousness in which phases of the same flow of consciousness become constituted phenomenally cannot be identical with these constituted phases, and of course they are not. What is brought to appearance in the actual momentary phase of the flow of consciousness, in its series of retentional moments [“reproductive moments” in the other version], are the past phases of the flow of consciousness."

Hagglund comments: "It is crucial that Husserl in the passage quoted above describes the absolute flow, which in his theory is the fundamental level of time-consciousness. The absolute flow is supposed to put an end to the threat of an infinite regress by being “self-constituting” and thereby safeguarding a primordial unity in the temporal flow. This solution requires that the subject appears to itself through a longitudinal intentionality that is not subjected to the constraints of a dyadic and temporal reflexivity. As we can see, however, Husserl’s own text shows that the absolute flow cannot coincide with itself. Even on the deepest level it is relentlessly divided by temporal succession. No phase of consciousness can intend itself. It is always intended by another phase that in turn must be intended by another phase, in a chain of references that neither has an ulterior instance nor an absolute origin.

...Husserl’s idea that the subject constitutes time is thus untenable. The subject does not constitute but is rather constituted by the movement of temporalization. The consequences of this inversion are considerable, since it is the supposed nontemporality of the absolute flow that allows Husserl to evade the most radical implications of retention and protention. If the reference to a nontemporal instance cannot be sustained, retention and protention cannot be posited as a unity in the “living presence” of subjectivity".

Thus, Hagglund takes aim at Husserl's ultimately incoherent claim that 'we lack names' for designating this 'priomordial source point' of 'absolute subjectivity' which is meant to put a stop to the infinite regress of the acts of perception. Husserl: "It is the absolute subjectivity and has the absolute properties of something to be designated metaphorically as a “flow”; the absolute properties of a point of actuality, a primordial source-point, “the now,” etc. In the actuality-experience we have the primordial source-point and a continuity of moments of reverberation. For all of this, names are lacking."

Hagglund: " As is evident from Husserl’s reasoning ... the latter idea and its connection to an “absolute subjectivity” ... answers to the phenomenological version of the metaphysics of presence. Husserl here claims that the flow of consciousness is an originary presence, a “primordial source-point” that constitutes time without itself being temporal. But whenever Husserl sets out to describe the pretemporal level, he will inevitably have recourse to a temporal vocabulary that questions the presupposed presence. This is not because the metaphors of language distort an instance that in itself is pretemporal but rather because the notion of absolute subjectivity is a projection that cannot be sustained—a theoretical fiction." -

The 'Postmoderns'Eh, that phrase might as well read that it's a fallacy to regard circles as anything other than squares. In any case, the conceptual issue would turn upon what notion of the 'self' is under consideration here. What kind of self could be 'conceptually shaped' and 'transfigured' by a 'practice of contemplation on an ideal'? If there's no mechanism and no theory of this transformation, then this is just another just-so story with no philosophical import.

-

The 'Postmoderns'In truth, the very idea of a practice of contemplation strikes me as an oxymoron. But I'd rather simply not talk about mysticism. I honestly have nothing good to say about it, and I'd prefer to be a bit more positive if I can. And the language of 'ground' and 'veils' is, I'm afraid, a bit too murky for me, I'm not sure how to go about answering without being too imprecise.

-

The 'Postmoderns'if we are immanent material beings and nothing but immanent material beings, the kind of (libertarian) freedom in the sense that I understand to be necessary for moral responsibility could be thought to be possible. — John

Eh, that kind of 'radical libertarian freedom' is a myth on par with a loving God for me, and a concept far more mystical and occult than anything a so-called postmodernist has ever subscribed to. If anything, such notions perpetuate suffering by mystifying the real sources of freedom which are only ever to be found in the here and now. Again, check out Ravven's book, where she utterly demolishes any notion of 'free will', showing it to be a theological remnant that has set back our thinking on freedom and responsibility by an order of centuries.

t's true that the universe can be made sense of; insofar as rational, discursive accounts and explanations can be given of it. But there remain aspects of human life, many of which are the most important to us, which cannot be explained in this way. The notion that some things must remain mysterious does not offend me or make we want to reject them in accordance with a demand that all must be explainable. On the contrary I feel happy on account of that. — John

I'd prefer to emphasize not that the universe can be made sense of, so much as it can be made sense of; that is, sense-making is a process, one that occurs in - or even as the universe itself. Immanence is not a thesis of absolute transparency, it is an affirmation of a praxis in or of being that includes history, material composition, political climate, cultural affordances, and so on. I will never know the sense of the world as the bee knows it, but this is not for 'transcendent' reasons, but immanent ones. Of the many definitions of immanence that Deleuze offered, the Spinozist one is the most apt: immanence means that one will never know what a body can do - not, at least, until that body is put into 'practice.' -

Reading Group: Derrida's Voice and PhenomenonYeah, I understand how the living present supposed to 'work', but the question at the heart of this chapter remains: is there a way, in principle to distinguish the living present from what is not? Husserl literally says: "In principle it is impossible to display any phase of this flow in a continuous succession and therefore to transform in thought the flow to such an extent that this phase is extended into identity with itself". It is not impossible on account of some contingent failure of thought - it is impossible in principle.

I get, of course - and Derrida even mentions it - that this is meant to serve as a bulwark against Brentano, but once you turn the living present into a sheer continuum, you're basically faced with the opposite problem: how then to 'introduce' representation into it? The charge of course is that Husserl basically slips it in under the table, hoping that it'll go unnoticed. The living present shades off, and then all of a sudden, at some unspecified - unspecifiable!, in principle - point, boom, you have representation.

I think you're right that Derrida does leave this point annoyingly underdeveloped, so I want to say more regarding the notion of the 'flow' here which is brought up in this chapter, but I dont have my PDFs on me ATM, so I'll try and expand upon this later. There's a bit in Husserl where he speaks of the failure of metaphor in regards to the flow, and there's a ton that can be developed in that breach. But again, I dont have my citations on me right now. -

Reading Group: Derrida's Voice and PhenomenonBut Husserl's 'own insistance' is just as much that retention and protention are 'the opposite of perception' - this isn't something Derrida is claiming as an 'external' supposition. Husserl actually said that.

-

Reading Group: Derrida's Voice and PhenomenonBut surely the key quote (from Husserl) is the one at the bottom of p.55 and runs over to p.56:

"If we now relate the term perception with the differences in the way of being given which temporal objects have, the opposite of perception is then primary memory and primary anticipation (retention and protention) which here comes on the scene, so that perception and non-perception pass continuously into one another".

Retention and protention are here - in Husserl - explicitly tokened as 'the opposite of perception'. And the quote that immediately follows speaks of a "continuous passage of perception into primary memory", a turn of phrase which explicitly makes primary memory something other than perception.

If anything, what's interesting about Derrida's move here is not to simply accuse Husserl of outright equivocation or contradiction, but to grasp the nettle and say that yes, this is exactly the case, that presence and non-presence, perception and non-perception both inhabit the 'blink of an eye' that is the 'now'. -

The 'Postmoderns'If anything, the insistence on immanence means that the universe can indeed be made sense of; that sense is engendered within the universe, and we don't have to gape like dead fish out of the water after the unnamable, the unknowable, and the inconceivable.

-

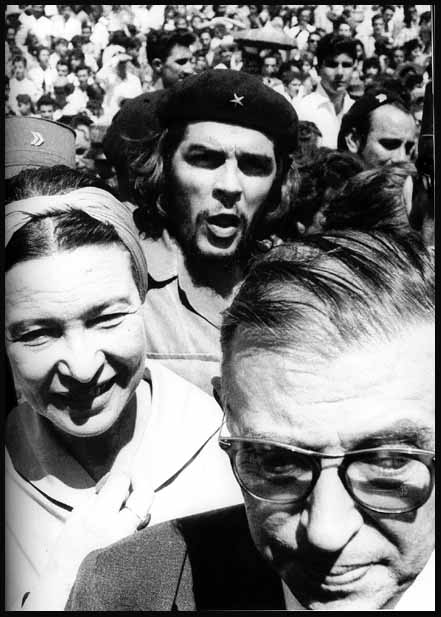

So who deleted the pomo posts?Yall forgetting the arch-hipster, Sartre:

But check out this selfie with Che and de Beauvoir:

(OK probably not a selfie but close enough). There's others with him and Castro too, really cool shit. -

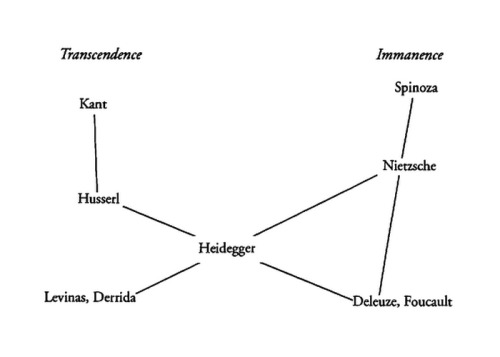

The 'Postmoderns'I think a common characteristic of PM ( and of most other strains of modern philosophy) consists in the denial of transcendence; which is to say a denial of spirit and genuine freedom. And I think this presumption of immanence has come to pass as a result of the domination of the scientific paradigm. — John

Man, you could have just opened with this, at least this is something vaguely concrete rather than just meta nonsense. Two points to make here. First, there's hardly a blanket 'denial of transcendence' within those thinkers you call postmodern. Without getting into it too much, Giorgio Agamben wrote an essay on Deleuze which, among other things, tracks the various positions of related authors, and he produced the following diagram, which I think is pretty accurate:

(Agamben, "Absolute Immanence", Potentialities)

So it's not exactly like all these thinkers hew to immanence. Secondly, immanence <> fatalism. Personally, one of my original motivations for looking into the tradition of immanence was that I always thought that if transcendence was the guarantor of freedom, then this would be no kind of freedom at all. Any kind of freedom, it seemed to me - and still does - ought to include one within it's circuit; only on an immanent basis could freedom mean anything at all. The two books I'd recommended on this subject are Alicia Juarrero's Dynamics in Action, and Heidi Ravven's The Self Beyond Itself. While I would hardly call both books postmodern (Juarrero comes out of systems theory, Ravven fuses Spinoza with neuroscience), they show quite convincingly what it would mean to configure freedom on an immanent basis. A more properly 'PM' book on this would be Judith Butler's Giving An Account of Oneself, where she shows quite convincingly that any kind of genuine ethical freedom would require that one be subject to forces beyond one's control.

In any case, to think that 'spirit and genuine freedom' are precluded by thinking in terms of immanence is misguided. All this apart from the fact that 'PM' is anything but defined by a commitment to immanence (consider Derrida's puzzlement over Deleuze's notion of immanence, in a piece written after the latter's death: " My first question, I think, would have concerned Artaud, his interpretation of the "body without organ," and the word "immanence" on which he always insisted, in order to make him or let him say something that no doubt still remains secret to us" - "I'll Have to Wander All Alone"). -

The 'Postmoderns'Not rejecting 'structuralist principles of meaning' (an awkward phrase to begin with) doesn't make one a structuralist. And again, what kind of structuralism are you referring to? Piaget? Levi-Strauss? Saussure? Rousset? Lacan? Not all of whom agree with each other, of course. But as usual, you simply trade in shallow labels and aren't able to advance any concrete assertions. I'm done with the empty shell of a thread.

-

The 'Postmoderns'Well go on then, make a damn statement with some examples and citations, and stop speaking in this uncommitted 'meta' manner about what you want to talk about. If you have a thesis to put forward, spit it out, and evidence it. Otherwise so far there's only been one instance of 'slipperiness' in this thread so far. Can you do more than hand wave here?

Maybe you can start with, to pick a random example out of thin air, Deleuze's affirmation that he was a pure metaphysician, in contrast to say, Derrida's attempt to 'deconstruct' all metaphysics. Perhaps you can also say something about Deleuze's commitment to pure immanence, as opposed to Derrida's rather more tangled relationship with transcendence. Or perhaps you can comment on Derrida's and Foucault's lifelong polemic reagarding their respective philosophical methodologies. I mean, I know that one of my interests, personally, is in finding points of convergence and divergence in Deleuze and Derrida. I've been struggling with that one for years, as have a multitude of other scholars in the field. Given the relative paucity of literature on the subject (trust me, I've looked high and low), you might have something interesting to say. Perhaps you can comment on the work on Len Lawlor, who is the kind of standard references when trying to coordinate these thinkers. Go on, show your work.

Streetlight

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum