-

Are you Lonely? Isolated? Humiliated? Stressed out? Feeling worthless? Rejected? Depressed?removed for privacy reasons

-

Why am I the same person throughout my life?I have the solution to this problem. I'll repost what I posted in another thread in response to Purple Pond.

I realize it is a strange idea that I am asking you to consider. Bear with me a bit and keep an open mind and consider the following. It is long, I know, but I don't know how else to get this across. If you get what I am trying to communicate, I think you'll see that it neatly solves all of the many puzzles of personal identity is a possible solution almost always left unconsidered.

Have you ever wondered why you find yourself being the particular person you happen to find yourself being? Don't look at it from an objective standpoint. Look at it from a subjective standpoint. Ask yourself, "Isn't it a little odd that I happen to find myself being Purple Pond and not someone or something else?"

First, consider that having a subjective perspective and being someone isn't an objective state of affairs. If you were to restrict yourself to third-person language and describe the world, there is one thing you couldn't declare: which of the entities in the world you are. You could say things like "Purple Pond is sitting in a chair looking at a screen" or "Oysteroid is wearing a white sweater" or "Purple pond says that he is Purple Pond". You couldn't say "I am Purple Pond." Finding yourself as a particular person, occupying a particular perspective, is something other than an objective fact, something that reveals itself to be more than a little mysterious if you think about it for a while.

What are the odds that out of all of the 3 pound hunks of matter out there in the vast universe or maybe even infinite multiverse, most of them lacking biology, you just happen to find yourself being a human in this special place and time? Did you win the cosmic lottery a hundred times over or something? Shouldn't you find it a bit surprising that you find yourself occupying such a privileged vantage point on the world? After all, it seems, you might have been a mouse instead, or a bacterium, or a cloud of dust or a rock in outer space.

Suppose we have a big bucket filled with a trillion marbles, one of which is gold, the rest of which are blue. We blindfold you and have you dig around and withdraw a marble. Then we ask you whether or not you should expect to take off the blindfold and find yourself holding a gold marble. Of course, the answer is no. With a random sample, you should expect to have a typical sample. If you do end up finding yourself with the one in a trillion golden marble, shouldn't you find this surprising?

Now consider how rare life is, how rare brains are, as far as hunks of matter go. Even as far as brains go, human brains are extremely rare. Even if the only thing it is possible for a self to find itself as is a human brain, isn't it weird that you are this particular one, and not another? What is it that determines which vantage point on the world you have?

From an objective perspective, of course Purple Pond is Purple Pond! How can it be otherwise! A is A! But that ignores the issue. The issue is your subjective perspective and your being someone.

People say, "I am my brain." What does that really mean? They are connecting something, their 'I', to something else, a particular brain, and saying that A is B. Isn't this a bit odd? What is this 'I'? To be a truly separate individual, it is as if you have your own 'I' and I have another one, as if each brain has a unique 'I' associated with it. But this idea, resembling the old individual soul idea, just adds mystery to mystery. Suppose you are a soul, even if you don't believe in such things. Why are you this soul and not a different one? Same problem. And on you would go with an infinite number of homunculi within homuncili.

Consider further what a strange idea it is that you can be something, some arbitrarily extended, but limited, collection of physical particles. People sometimes ask what it must be like, if it is like anything at all, to be a rock. Notice what they are doing! Is there some magical boundary around a rock other than the one we impose when we see a rock and identify it as such, mentally separating it from its surroundings? If a rock, which is a collection of many smaller things, why stop the collection at that point? Why not a pile of rocks? Why not the mountain? Why not the planet? Why not the whole universe?

But isn't it strange that you could be a collection of things in the first place? Let's simplify this so that the issue becomes more clear. Suppose you were to find yourself being a thing that is composed of exactly two things, perhaps two quarks. How can you be a pair of things? Isn't that a weird idea? How is it that you have this span, that what you are can extend beyond just one thing to include more?

Gilbert Ryle used to talk to his students about the question of whether there are three things in the field, two cows and a pair of cows. This makes me chuckle.

When people claim to be a brain or a whole body or whatever, they are saying that they are a huge collection of things, that their identity has this incredible span. Why not half the brain? Why not a single neuron? Why not two brains? Why not everything?

And then you get into all the usual problems of personal identity. Are you the same person over time? But the atoms in your body are changing. The form is changing. Whether you are the very atoms or the pattern in which they are arranged, this creates problems.

If what you actually are is this particular, arbitrary set of particles that currently composes your brain, then after a while, you become dispersed and might end up being split up over multiple bodies as other creatures eat the matter that once composed your body. And if you are these specific particles, realize that they were once separated and belonged to many different organisms. What are the odds that the collection that is you just happened to come together in one brain, all at the same time?

No, you couldn't simply be identical with this collection of atoms! What about the form, the pattern? If you are a particular pattern, consider that the form is constantly changing! You would only exist momentarily! There would be a succession of many, many separate selves, each living a moment in the course of a life.

That doesn't make sense either, does it? So what are you? Consider that you already accept, if you believe that you are a brain or a body, that what you are spans multiple things. It involves multiple particles, multiple cells, multiple organs, a span of time with many states, and so on. It is just that you think that what you are ends with your skull and your birth and death. But why would it end there? Is that some kind of magical boundary that encapsulates an ego? Does a skull boundary define an 'I'?

I think we tend to find it easy to accept that we are a brain, and to not notice that we are thinking that we are a multitude, because of the fact that, because of how our minds carve up the world into things, we think of the brain as one thing, like Ryle's pair of cows.

And then you can consider all the questions that arise with teleporters and the like. If we read all the information describing your body, destroying your body in the process, and then assemble a copy at a distant location, when the person steps out of the teleporter, is that person you? Do you, the same you that you are now, find yourself then on the other side? What if we make two copies? Which one will you be, if any? Or did you die?

How do you know that your form propagating from moment to moment isn't just like that teleporter? Is the experiencer of your perspective this moment the same one as an hour ago? I would say yes, obviously. Otherwise you couldn't experience the flow of time. Your identity must span time in order for you to experience change. And your identity must span some space and material in order for you to have a unified experience of all that your brain is doing, even to experience an apple as an apple, with its combination of color, shape, meaning, and so on, the processing of which involves many brain regions.

So you already have span, both temporal and spatial. You are already more than one thing and more than one state of those things. So why do you think that what you are is limited to this body and its lifespan?

Consider how the idea that you are simply that which is everything, that it is all one and you are it, would solve all of these problems in one fell swoop.

Why do you find yourself being Purple Pond? Well, being everyone and everything, you'd naturally expect to find yourself being Purple Pond. Consider the marble picking again. If you were allowed to hold all the marbles, should you be surprised to find yourself holding the golden one?

Think about it probabilistically. If you are in one of two scenarios, with you not knowing which, and you had to guess which one you are in, which should you bet on, the one in which your case is far from typical or the one in which your case is typical or even inevitable? For example, suppose we flip a coin and determine which of two prizes you get: A, all the marbles, including the golden one, or B, just one marble selected at random. Now suppose that before we tell you the result of the coin flip, we tell you that you definitely have the golden marble. Which should you expect to be true, that the coin chose A or B? You should guess A. In that case, having the golden marble is something you'd expect. In the other case, it would be a big surprise.

The fact that you find yourself being Purple Pond, being a brain at all, being alive at all, being in an inhabitable universe at all, and so on, is absolutely inevitable if you are everything, and astronomically unlikely if you are just one arbitrary three pound thing on a particular arbitrary planet, in a particular arbitrary galaxy, and so on.

Think about a lottery win. If you describe the situation objectively, it is not very surprising when someone wins. But if you find that you are the winner, that is a different thing, isn't it? That is surprising! But notice that it suddenly ceases to be surprising, even subjectively, if you happen to be everyone.

This idea even clears up all the confusion about the anthropic principle and the fine-tuning of the cosmos and whatnot. Why does the universe seem so fine-tuned? Suppose there is an infinite multiverse containing all possible universes. In one of them at least, these conditions will prevail. And if you are everywhere, naturally, you should expect to find yourself alive in a universe fine-tuned for life! But if you aren't everything, if you are just one arbitrary three pound hunk of matter, inexplicably having both span across a multiplicity of things and a limit to that span, then your situation is indeed unusual and suprising to find yourself in.

But there is a natural objection to all of this. Why don't you feel yourself being me and everyone else? Why don't you know that you are everyone? Why can't you access my memories?

There are some famous cases in which people with severe epilepsy have undergone a procedure in which the corpus callosum in their brain has been severed, effectively isolating the two hemispheres. If you aren't familiar with this, I'd suggest researching and reading about split-brain surgery. What results from this is a situation in which it seems that there are now two selves, one for each hemisphere. Using clever methods, you can ask one hemisphere a question and give it information while avoiding giving any information to the other. You quickly find that if you ask one hemisphere questions about what you have only shown the other hemisphere, the answers contain no information about it. You can show that there is no integration of information between the hemispheres. Further, the two hemispheres seem to have distinct desires, distinct plans for the future, and so on. And sometimes, one hand will try to button up a jacket while the other tries to keep it unbuttoned, and so on. Suddenly, it seems that there are two people in one skull, each controlling half the body.

What has happened here? Can your self, the very you that you are, be divided into two? If you undergo such a procedure, which of the hemispheres will you find yourself being afterwards?

Consider another hypothetical scenario. We take a guy named Bob, who is an amnesiac who cannot remember new information for longer than a few minutes, and we place him in a room with a chalkboard mounted on the wall. We show him things, give him experiences, and he records what he observes on the board. When we ask him what we have told him or what he has experienced, he consults the board. It basically serves as his memory. Now, suppose that we take him to a second room, room B, also with a board. But this board is blank. In this room, he does not have any access to what he wrote on the board in room A. We can replicate all the experiments from the split-brain studies using Bob in these two rooms, and we can show that there is no information integration between the rooms. In room B, Bob cannot give information about what he observed in room A, and vice versa. And he can't connect things observed in the two rooms.

Obviously, we can't conclude from this that there are two separate people here, one in room A and one in room B. Bob is one person regardless of the inability to integrate information between the rooms. The only issue here is that there is no way for information to pass from room A to room B and vice versa. While in room B, Bob knows nothing of his life in room A. He doesn't remember being in room A. He might have written a concerto in room A, but he would know nothing of it while in room B. If we give him a portable notebook, he might then integrate information between the two rooms, but without such a device, there is no reason to expect him to have access to information in the other room. The same goes for the two hemispheres in the split-brain. The corpus callosum is like a notebook allowing information to pass between hemispheres.

What's the point of this Bob business? I'd suggest that the very same situation holds for us as seemingly separate individuals. Our two brains are like the two rooms. There is one experiencer with both perspectives simultaneously, but over there, in your brain, there are obviously no memories from my brain. How would they get there? They'd have to get there by some local physical mechanism. In this brain over here, I lack access to what is stored in that brain over there. In the Oysteroid brain, I find no Purple Pond memories, naturally, and vice versa. And that's all there is to it. That's why we think we are distinct selves. In actuality, I believe, that which we are, that deepest inner witness that looks out from behind these eyes, is everywhere and is everything. And it isn't a separate self inhabiting the multiverse, as if there is one big soul assigned to one big multiverse. No! It is all just one whole. Your very self is the very substance of it all. The scenario with Bob isn't a perfect analogy here, as Bob is separate from the rooms.

There is one substance and it experiences all of its modifications and relations and is everywhere present to itself. And if you want to know what it is like to be it, just ask yourself. You're it. You're everything.

It isn't like reincarnation, where you can look forward to another life. No, you are living them all simultaneously and always. You are already over here, experiencing my life. You are already beyond the life of Purple Pond. You just can't access this information from there. While in that room, you don't know that you are also in this room and all the other rooms.

Take this seriously. Think about it. And realize that there is never again cause for envy. When you see someone else enjoying some life that you don't have, know that you have it, that you are that person. Also know that when you hurt another being, you are hurting yourself. It is none other than you that has the experience on the other side of whatever you do to another.

If you have made it to the end, thanks for giving all this your consideration! -

My doppelganger from a different universe

I find that hard to believe.

I realize it is a strange idea that I am asking you to consider. Bear with me a bit and keep an open mind and consider the following. It is long, I know, but I don't know how else to get this across. If you get what I am trying to communicate, I think you'll see that it neatly solves all of the many puzzles of personal identity is a possible solution almost always left unconsidered.

Have you ever wondered why you find yourself being the particular person you happen to find yourself being? Don't look at it from an objective standpoint. Look at it from a subjective standpoint. Ask yourself, "Isn't it a little odd that I happen to find myself being Purple Pond and not someone or something else?"

First, consider that having a subjective perspective and being someone isn't an objective state of affairs. If you were to restrict yourself to third-person language and describe the world, there is one thing you couldn't declare: which of the entities in the world you are. You could say things like "Purple Pond is sitting in a chair looking at a screen" or "Oysteroid is wearing a white sweater" or "Purple pond says that he is Purple Pond". You couldn't say "I am Purple Pond." Finding yourself as a particular person, occupying a particular perspective, is something other than an objective fact, something that reveals itself to be more than a little mysterious if you think about it for a while.

What are the odds that out of all of the 3 pound hunks of matter out there in the vast universe or maybe even infinite multiverse, most of them lacking biology, you just happen to find yourself being a human in this special place and time? Did you win the cosmic lottery a hundred times over or something? Shouldn't you find it a bit surprising that you find yourself occupying such a privileged vantage point on the world? After all, it seems, you might have been a mouse instead, or a bacterium, or a cloud of dust or a rock in outer space.

Suppose we have a big bucket filled with a trillion marbles, one of which is gold, the rest of which are blue. We blindfold you and have you dig around and withdraw a marble. Then we ask you whether or not you should expect to take off the blindfold and find yourself holding a gold marble. Of course, the answer is no. With a random sample, you should expect to have a typical sample. If you do end up finding yourself with the one in a trillion golden marble, shouldn't you find this surprising?

Now consider how rare life is, how rare brains are, as far as hunks of matter go. Even as far as brains go, human brains are extremely rare. Even if the only thing it is possible for a self to find itself as is a human brain, isn't it weird that you are this particular one, and not another? What is it that determines which vantage point on the world you have?

From an objective perspective, of course Purple Pond is Purple Pond! How can it be otherwise! A is A! But that ignores the issue. The issue is your subjective perspective and your being someone.

People say, "I am my brain." What does that really mean? They are connecting something, their 'I', to something else, a particular brain, and saying that A is B. Isn't this a bit odd? What is this 'I'? To be a truly separate individual, it is as if you have your own 'I' and I have another one, as if each brain has a unique 'I' associated with it. But this idea, resembling the old individual soul idea, just adds mystery to mystery. Suppose you are a soul, even if you don't believe in such things. Why are you this soul and not a different one? Same problem. And on you would go with an infinite number of homunculi within homuncili.

Consider further what a strange idea it is that you can be something, some arbitrarily extended, but limited, collection of physical particles. People sometimes ask what it must be like, if it is like anything at all, to be a rock. Notice what they are doing! Is there some magical boundary around a rock other than the one we impose when we see a rock and identify it as such, mentally separating it from its surroundings? If a rock, which is a collection of many smaller things, why stop the collection at that point? Why not a pile of rocks? Why not the mountain? Why not the planet? Why not the whole universe?

But isn't it strange that you could be a collection of things in the first place? Let's simplify this so that the issue becomes more clear. Suppose you were to find yourself being a thing that is composed of exactly two things, perhaps two quarks. How can you be a pair of things? Isn't that a weird idea? How is it that you have this span, that what you are can extend beyond just one thing to include more?

Gilbert Ryle used to talk to his students about the question of whether there are three things in the field, two cows and a pair of cows. This makes me chuckle.

When people claim to be a brain or a whole body or whatever, they are saying that they are a huge collection of things, that their identity has this incredible span. Why not half the brain? Why not a single neuron? Why not two brains? Why not everything?

And then you get into all the usual problems of personal identity. Are you the same person over time? But the atoms in your body are changing. The form is changing. Whether you are the very atoms or the pattern in which they are arranged, this creates problems.

If what you actually are is this particular, arbitrary set of particles that currently composes your brain, then after a while, you become dispersed and might end up being split up over multiple bodies as other creatures eat the matter that once composed your body. And if you are these specific particles, realize that they were once separated and belonged to many different organisms. What are the odds that the collection that is you just happened to come together in one brain, all at the same time?

No, you couldn't simply be identical with this collection of atoms! What about the form, the pattern? If you are a particular pattern, consider that the form is constantly changing! You would only exist momentarily! There would be a succession of many, many separate selves, each living a moment in the course of a life.

That doesn't make sense either, does it? So what are you? Consider that you already accept, if you believe that you are a brain or a body, that what you are spans multiple things. It involves multiple particles, multiple cells, multiple organs, a span of time with many states, and so on. It is just that you think that what you are ends with your skull and your birth and death. But why would it end there? Is that some kind of magical boundary that encapsulates an ego? Does a skull boundary define an 'I'?

I think we tend to find it easy to accept that we are a brain, and to not notice that we are thinking that we are a multitude, because of the fact that, because of how our minds carve up the world into things, we think of the brain as one thing, like Ryle's pair of cows.

And then you can consider all the questions that arise with teleporters and the like. If we read all the information describing your body, destroying your body in the process, and then assemble a copy at a distant location, when the person steps out of the teleporter, is that person you? Do you, the same you that you are now, find yourself then on the other side? What if we make two copies? Which one will you be, if any? Or did you die?

How do you know that your form propagating from moment to moment isn't just like that teleporter? Is the experiencer of your perspective this moment the same one as an hour ago? I would say yes, obviously. Otherwise you couldn't experience the flow of time. Your identity must span time in order for you to experience change. And your identity must span some space and material in order for you to have a unified experience of all that your brain is doing, even to experience an apple as an apple, with its combination of color, shape, meaning, and so on, the processing of which involves many brain regions.

So you already have span, both temporal and spatial. You are already more than one thing and more than one state of those things. So why do you think that what you are is limited to this body and its lifespan?

Consider how the idea that you are simply that which is everything, that it is all one and you are it, would solve all of these problems in one fell swoop.

Why do you find yourself being Purple Pond? Well, being everyone and everything, you'd naturally expect to find yourself being Purple Pond. Consider the marble picking again. If you were allowed to hold all the marbles, should you be surprised to find yourself holding the golden one?

Think about it probabilistically. If you are in one of two scenarios, with you not knowing which, and you had to guess which one you are in, which should you bet on, the one in which your case is far from typical or the one in which your case is typical or even inevitable? For example, suppose we flip a coin and determine which of two prizes you get: A, all the marbles, including the golden one, or B, just one marble selected at random. Now suppose that before we tell you the result of the coin flip, we tell you that you definitely have the golden marble. Which should you expect to be true, that the coin chose A or B? You should guess A. In that case, having the golden marble is something you'd expect. In the other case, it would be a big surprise.

The fact that you find yourself being Purple Pond, being a brain at all, being alive at all, being in an inhabitable universe at all, and so on, is absolutely inevitable if you are everything, and astronomically unlikely if you are just one arbitrary three pound thing on a particular arbitrary planet, in a particular arbitrary galaxy, and so on.

Think about a lottery win. If you describe the situation objectively, it is not very surprising when someone wins. But if you find that you are the winner, that is a different thing, isn't it? That is surprising! But notice that it suddenly ceases to be surprising, even subjectively, if you happen to be everyone.

This idea even clears up all the confusion about the anthropic principle and the fine-tuning of the cosmos and whatnot. Why does the universe seem so fine-tuned? Suppose there is an infinite multiverse containing all possible universes. In one of them at least, these conditions will prevail. And if you are everywhere, naturally, you should expect to find yourself alive in a universe fine-tuned for life! But if you aren't everything, if you are just one arbitrary three pound hunk of matter, inexplicably having both span across a multiplicity of things and a limit to that span, then your situation is indeed unusual and suprising to find yourself in.

But there is a natural objection to all of this. Why don't you feel yourself being me and everyone else? Why don't you know that you are everyone? Why can't you access my memories?

There are some famous cases in which people with severe epilepsy have undergone a procedure in which the corpus callosum in their brain has been severed, effectively isolating the two hemispheres. If you aren't familiar with this, I'd suggest researching and reading about split-brain surgery. What results from this is a situation in which it seems that there are now two selves, one for each hemisphere. Using clever methods, you can ask one hemisphere a question and give it information while avoiding giving any information to the other. You quickly find that if you ask one hemisphere questions about what you have only shown the other hemisphere, the answers contain no information about it. You can show that there is no integration of information between the hemispheres. Further, the two hemispheres seem to have distinct desires, distinct plans for the future, and so on. And sometimes, one hand will try to button up a jacket while the other tries to keep it unbuttoned, and so on. Suddenly, it seems that there are two people in one skull, each controlling half the body.

What has happened here? Can your self, the very you that you are, be divided into two? If you undergo such a procedure, which of the hemispheres will you find yourself being afterwards?

Consider another hypothetical scenario. We take a guy named Bob, who is an amnesiac who cannot remember new information for longer than a few minutes, and we place him in a room with a chalkboard mounted on the wall. We show him things, give him experiences, and he records what he observes on the board. When we ask him what we have told him or what he has experienced, he consults the board. It basically serves as his memory. Now, suppose that we take him to a second room, room B, also with a board. But this board is blank. In this room, he does not have any access to what he wrote on the board in room A. We can replicate all the experiments from the split-brain studies using Bob in these two rooms, and we can show that there is no information integration between the rooms. In room B, Bob cannot give information about what he observed in room A, and vice versa. And he can't connect things observed in the two rooms.

Obviously, we can't conclude from this that there are two separate people here, one in room A and one in room B. Bob is one person regardless of the inability to integrate information between the rooms. The only issue here is that there is no way for information to pass from room A to room B and vice versa. While in room B, Bob knows nothing of his life in room A. He doesn't remember being in room A. He might have written a concerto in room A, but he would know nothing of it while in room B. If we give him a portable notebook, he might then integrate information between the two rooms, but without such a device, there is no reason to expect him to have access to information in the other room. The same goes for the two hemispheres in the split-brain. The corpus callosum is like a notebook allowing information to pass between hemispheres.

What's the point of this Bob business? I'd suggest that the very same situation holds for us as seemingly separate individuals. Our two brains are like the two rooms. There is one experiencer with both perspectives simultaneously, but over there, in your brain, there are obviously no memories from my brain. How would they get there? They'd have to get there by some local physical mechanism. In this brain over here, I lack access to what is stored in that brain over there. In the Oysteroid brain, I find no Purple Pond memories, naturally, and vice versa. And that's all there is to it. That's why we think we are distinct selves. In actuality, I believe, that which we are, that deepest inner witness that looks out from behind these eyes, is everywhere and is everything. And it isn't a separate self inhabiting the multiverse, as if there is one big soul assigned to one big multiverse. No! It is all just one whole. Your very self is the very substance of it all. The scenario with Bob isn't a perfect analogy here, as Bob is separate from the rooms.

There is one substance and it experiences all of its modifications and relations and is everywhere present to itself. And if you want to know what it is like to be it, just ask yourself. You're it. You're everything.

It isn't like reincarnation, where you can look forward to another life. No, you are living them all simultaneously and always. You are already over here, experiencing my life. You are already beyond the life of Purple Pond. You just can't access this information from there. While in that room, you don't know that you are also in this room and all the other rooms.

Take this seriously. Think about it. And realize that there is never again cause for envy. When you see someone else enjoying some life that you don't have, know that you have it, that you are that person. Also know that when you hurt another being, you are hurting yourself. It is none other than you that has the experience on the other side of whatever you do to another.

If you have made it to the end, thanks for giving all this your consideration! -

My doppelganger from a different universe

...am I the same person?

What do you mean by "person"? Are you asking if the two bodies are the same body, if they are in fact not distinct after all, being one body? A is A? Or are you asking something more along the lines of whether there are two different subjects, two different experiencers?

If you are talking about the bodies, if they are defined as distinct and if there is some way to finally distinguish them, some way to show the two universes to be distinct, then I guess they are distinct, in which case they can't be the same body. If A is not B, then A cannot be B. If A is A, A cannot be other than A.

But if they are truly indistinguishable, by the identity of indiscernibles, it would seem that it makes no sense to say that there are two separate things. If two universes are perfectly identical in every possible way and there is no way to tell the difference, how can they be said to be different? Are they separated somehow, say spatially? I'm not sure what a spatial separation between universes would mean, but in that case, they wouldn't be identical. There would be at least one difference, namely, that of location.

If you are getting more at the subjective experience and perspective, then I'd say definitely yes. That which fundamentally has the experiences finds itself being both people. You, the real you, inhabit both universes. But there is nothing particularly special here about the fact that the two bodies are identical and yet distinct. You, the real you, also find yourself being everyone and everything else. You are me as well. You find yourself occupying every perspective.

There is only one real self. There are no truly separate individuals. The illusion of separate selves is the result of incomplete information integration between different parts of the world. -

A Simple Argument against DualismI haven't read every comment in the thread, so I hope I'm not repeating anything. After reading quite a few, a number of considerations come to mind.

First, regarding the idea that in order for two things to interact, that they must occupy the same space, consider a "space" in a computer simulation or game and the computer, the code, and the world outside of the sim and how they can interact. You could have a virtual space in the simulation in which there are "local", "physical" interactions according to laws given by the code. A body in that world could be an avatar for some entity that isn't an occupant of that virtual space. And some means of interaction could be provided for in the code that would not be detectable in the game world. We do such things all the time in MMORPGs. It is clearly not the case that the things in the game world cannot interact with things outside of it. A player interacts with that world through input devices, but that input is not detectable from within the game world.

Sure, you might then argue that there really is no game world, that everything involved actually resides in the higher, truly physical world, that all "interaction" inside the virtual world is illusory. But such a situation could also be the case in our physical world. Even body-to-body interactions as we imagine them might not be truly mediated via physical mechanisms through space and time. Their true background and what gives rise to correlations between them might go deeper and might be inaccessible to us, belonging to a deeper world that we can't know directly through this one. I'd say that the whole concept of the physical is rather muddy anyway. We don't really understand "physicality" or even substantiality as well as we tend to think we do. Nor do we understand consciousness. Reducing everything to one or the other and then declaring the problems and mysteries eliminated is foolishness.

How do thing-to-thing interactions in the physical world actually occur? Do they occur? Doesn't such an idea assume that there are multiple truly distinct things interacting? In order for there to be interaction in the strict sense of the word, doesn't this require that multiple things are involved? And doesn't this actually run afoul of what Spinoza argued about the problem with multiple substances? If you conceive of particles as truly separate, independent things, one from another, things each standing on their own, so to speak, having self-existence, you are talking about multiple substances, substance here being used in the traditional metaphysics sense. And multiple substances interacting is usually considered problematic. For one thing, if they are truly independent, why are they the same in so many ways? Why are all electrons basically identical? And why do they occupy the same space? How would truly independent substances have anything in common? And if things are not actually separate, then how can they be said to interact?

It could be that the concept of interaction itself is problematic, as it relies on there being a true multiplicity. Instead, all of reality might involve wholeness.

What are we really talking about anyway with causality? Do we even know?

Also, consider that space at least, if not time also, is possibly emergent and not necessarily fundamental. It seems to me a rather old-fashioned way of seeing things to think of atoms and the void as ultimate fundamentals, and yet most people seem to think in this fashion when thinking about the physical, even though modern physics has given us plenty of reason to raise questions here. For one thing, such a view leaves space, time, and atoms unexplained, as well as the laws that govern them. What is space? Is it just an emptiness or absence of things, or is it substantial? Is it a something itself? Is there a "fabric" of space? What is time? What are atoms? How do they interact? How is it that they have substantiality? How is it that there are multiple things? Why are there many identical things? Why do they have the particular properties they do?

In Einstein's theories, space gains its own degrees of freedom and seems to cease to be the empty void of Democritus that people still seem to imagine. What is it then? If spatial geometry can change, what is it that is changing? And what is it exactly that determines that a certain thing is in a certain place in space? How does that thing "know" where it is? How does the universe "know" where it is and whether it will interact with another thing?

There are all sorts of interesting things to think about. If the only thing in the universe is a single astronaut floating in space, where is he? How fast is he moving? Suppose there is another astronaut in view. Who is moving? There is relative motion. Without the other, velocity is undefined. With two astronauts, information about each is available to the other by way of things like light (maybe the astronauts have flashlights), gravity, and so on. But drop down to the level of a single sub-atomic particle. Until an interaction occurs, aren't its position and momentum undefined? At that level, unlike at the level of a large astronaut, where many, many interactions are involved in seeing another astronaut, interactions are comparatively rare. As a single tiny particle, you can't "see" the world around you. You aren't big enough be struck by enough photons or whatever in order to gain information about your surroundings. Prior to an interaction, it would seem, you are effectively isolated, and so your position, momentum, and so on, are undefined. Only upon interaction does any of this become defined. And since things are quantized and discrete, interactions are seemingly on and off. If light were continuous, particles could maybe be thought to receive tiny quantities of light from all around, from many, many objects, and thus not be so blind. The discreteness and quantization gives a different picture. But if you need interaction to gain definite position and momentum, how is it determined whether the interaction happens or not? If it isn't "known" where the particles are, how is it "known" if they collide? Seemingly, interaction is needed to generate information about relative states, but information about relative states is needed to decide if interaction occurs. What is it that keeps track of their respective positions and momenta, if anything? A real position in a real space? What does that mean? Is that compatible with the uncertainties of QM? In a computer simulation of particles, we keep track in the computer's memory. The computer "knows" and compares the positions. What about in the physical world?

How is any of this relevant to the discussion? I think there are questions that few ask about how any sort of interaction occurs. An interaction between two particles in space might require a third unknown factor, one transcending space. And if such other factors could be involved, why couldn't they possibly mediate mind-matter interactions? We just don't know enough to rule such things out. We don't know what mind really is. We don't know what matter/energy really is. We don't know what space is. We don't know what interaction really is. We don't understand causation. So deciding what is possible by means of arguments such as the one presented in the OP is more than a little misguided, it seems to me.

Recently, there has been some stir in the physics world over ER=EPR, and some are beginning to think, in possible glimmers of a theory of quantum gravity, that space itself is emergent and is "stitched together" by entanglement, and represents a sort of network of particles (not particles in the intuitive "tiny rock" sense). But if space is emergent in this sense, where do the particles that, by their entanglement structure, give rise to it, themselves reside? Another space? Why is that needed?

Where, for that matter, is the universe located? Does it have location?

Consider a computer program in which you define a bunch of nodes with "links". Create rules such that information can be moved from node to node, but only across links. Information can be passed at a rate of only one link per time step. Suppose you have nodes linked in a series such as A-B-C-D-E.... Information can go from A to B to C, but never A directly to C, since no such link exists. What happens here is that a sort of space emerges, a one-dimensional space. But in reality, A, B, C, D, E, and so on, are not actually spatially located. They are distinguished logically or informationally only. Spatial "proximity" here takes on a new meaning, having to do with the arbitrary structure of the network. The nodes themselves actually have no location in any true space.

Our space could be analogous to this in that there might not be any true, ultimate space in which particles reside. Reality might be more fundamentally logical/informational.

In our computer program, we could create more emergent spatial dimensions by linking nodes in more ways. We could have A1 linked to both B1 and to A2, for example, giving something like rows and columns. You could then have a 2D "space" "inside" the network, in which such games as Conway's Game of Life could happen. If you are an inhabitant of such a world, it might appear that all causal interaction is truly happening at the level of the things inside that space, between things locally acting on one another, one cell literally touching and thereby influencing its neighbor. In reality, what is responsible for that apparent interaction is something altogether inaccessible to the contents of the game world. It has more to do with the computer running the program and storing information in variables, executing conditionals, comparing variables, and so on. Similarly, in our world, many things might be completely hidden from us. Many of the conditions for the possibility of what we see happening might be based in something happening in a realm transcending the one we have access to.

Remember that correlation doesn't demonstrate causation. What might at first appear to be A causing B might in fact be C causing both A and B. Every time the mercury in the thermometer rises beyond a certain point, I also start sweating, but it would be a mistake to conclude that the rising mercury is causing me to sweat. And realize that when we think we observe physical causation, all we are really seeing is correlation. Every time X occurs, Y occurs. We are seeing patterns in our experience. We don't have any deep justification for our belief that one billiard ball striking another is fundamentally and finally what causes it to move.

Consider being stuck in a dream you can't wake from and trying, from that vantage point, to address certain factors that affect the dream world, such as your physical body. You cannot find that which governs the contents of the dream inside the dream. You can't find, strictly within the dream world, the brain that dreams it. You could not, for example, excise your brain tumor through the dream world. Similarly, in an MMORPG, you cannot find the player of the game inside the game world. You cannot find the computer on which the game is running inside the game world. You cannot find the code inside the game world.

Suppose we create a simulation in which we have a physics that works at the particle level and we evolve a complex world there built of these virtual particles. Now imagine that a scientist composed of such particles studies that world experimentally and adheres to the idea that reality consists only in what can be experimentally verified. Could that scientist, by means of his experiments, ever gain access to the computer on which his world is running? Could he discover the programmers? He might manage to discover laws, and thus, to some small extent, something of the code behind the simulation, but that's about all. So if he were to define reality as being limited to that which is composed of the particles in his world and their interactions, and that which is verifiable by experiments performed on these particles, he would be making a mistake, wouldn't he? He'd be rather short-sighted, but understandably so.

Also, what relevance might Kant have in this discussion? In his view, aren't space and time categories of the understanding? How does this affect the question of interaction between mind and body?

I think it even possible that the physical world is something that happens emergently inside mind, or is in some sense the content of mind, or represents the structure, seen at a certain level, of a kind of mental activity. After all, physics seems to reduce to math and information and maybe ultimately logic, which are themselves decidedly not very "stuff-like", seemingly rather more like cognition. We still, because of physics history, call the small constituents of reality "particles", but when you really examine the concept, the particles of modern physics are not at all what we intuit when using that word. A picture often presented in physics is that of a photon, a discreet packet of energy, being absorbed by an electron and thereby converted into a higher energy state of that electron. What is really happening here? Do we really understand matter-energy equivalence? Consider that a particle itself can be converted into momentum. What is this "stuff" then?

And from the perspective of the photon, because of length contraction, there is no distance or time interval in the crossing. The source and destination electrons are, for the photon, co-located or touching. Perhaps photons aren't real particles moving through space. Maybe space itself isn't what we imagine it to be. A seeming travel of a photon, which has never been observed by the way, might be one electron directly exchanging information with another by a sort of "local" action, transferring energy from one to another.

As little as we currently understand about the deep nature of things, I'd say it is extremely premature to claim that we know that things located in space and things not located in space cannot be related. Also, the idea that there can be nothing real that isn't located in space is absurd, space itself being the perfect example. Is space located in space? No? Is it therefore unreal? The laws of physics, mathematics, and logic are all real and not spatially located.

If space is emergent, as it seems it might well be, then even the things seemingly in space aren't truly located in space. And this would cause trouble for the idea of a problem with interaction between spatially located things and things not spatially located. Instead, we'd be talking about relationships where none of the things involved have true spatial location.

And what if space emerges in mind? What if matter and space are contents of mind? Mind is then clearly not in space and yet it is easy to see that mind could be said to have some bearing on its contents. If you have trouble with this in the big, real world, consider how the argument in the OP would play in a dream. The "dream-physical", or the content of the dream world, lives in the dream world, while the mind transcends it, and yet they clearly are related. But of course, this is not truly a dualistic picture. But a kind of dualism could certainly be apparent or emergent at a certain level. -

Philosophical alienation

Surprised that this thread died down, oysteroid seems to have abandoned it as well.

I've been meaning to respond, but have been rather busy with some family matters. And there is so much that I feel needs to be examined/said in response to what has been said that I feel a bit overwhelmed with the prospect of responding adequately. I'll see if I can manage a decent response. Or maybe not. We'll see. Just thinking about it makes me feel tired! ;)

One thing I will say now is that since you expressed such disdain for Jordan Peterson, I've watched some more of his videos to see what he has to say. I have mixed feelings about his work. What is it about what he says that you have such a problem with? Just curious. -

Philosophical alienationAgustino, I'll deal with you later... ;) I need to go for a run and do some things other than staring at this screen!

-

Philosophical alienationWell, the simplest and most elegant example I can provide to you is of the Cynics. They disregarded almost off of the things you have mentioned in your post. — Posty McPostface

Regarding the Cynics, the Stoics, Socrates, Buddha, Jesus, Pythagoras, Krishna, and most other personalities that appear in very old texts, reports of their lives, actions, and words are not very reliable and tend to be full of exaggeration, fabrication, and downright deification. It was common back then for later writers to present their words as those of a dead sage. In the case of Socrates/Plato, half of what Socrates supposedly said was Plato putting words in his mouth. We don't know what these people were really like or how their ideas worked for them in actual practice. Hell, Pythagoras was said to have a golden thigh and to bilocate! Do you believe that? I'd say that reports of people completely free of the concerns I am talking about are likely equally unreliable.

Besides, didn't most of these people have a social life? And didn't they enjoy some esteem? A sense of importance? And so on? We don't hear from those who truly abandoned society and can only guess at their mental state.

Was Diogenes perfectly content in the lifestyle he chose? How do you know? I don't get the impression of a man at peace when I read about him.

Show me a real, live, happy person free of such concern due to the adoption of such ideas.

Also, these people felt they were breaking ground and found meaning in what they were doing, no? And they were engaged, trying to affect the world. They didn't withdraw and hide in their rooms!

Let's consider the actions of Diogenes, the public masturbation and pissing on people, for instance. What was that all about? Freedom from opinion? Really? He was obviously making a show of his rebellion against their norms! A rebel isn't free of what he rebels against. A conformist's behavior, thought, and appearance are a direct function of the norms of society, or of public opinion. An anti-conformist's (not a nonconformist's), or a rebel's, is still a function of public opinion, only the inverse, and so such a person is still a slave to what others think. A true nonconformist's ways would be independent of society and probably not terribly remarkable or shocking, maybe even agreeing with society in most ways, as such a person might see the sense in some of the things normal in society, language conventions for example, or stopping at red lights, or pooping in toilets. Such a person would be indifferent to what people think, not rebelling against it, not violating taboos for the sake of violating taboos. Do you think a punk rocker in the 80s in public with a pink mohawk was free of concern for the opinions of those who sneered at his appearance? Hardly. Really, such behavior is kind of juvenile, if you ask me.

I would suggest that Diogenes was probably an attention-hound! He obviously got a lot of it! He was like the shock-rocker of his day. He was a celebrity! He probably reveled in it! He even got the attention of Alexander the Great! He was about as free from opinion as Marilyn Manson! -

Philosophical alienationThere's a lot to address here. I've been a bit overwhelmed with things to do today. I'll try to answer adequately soon.

Agustino, it seems to me that you've misunderstood some things and made some assumptions. I guess I need to make my position more clear. And no, I am not big Jordan Peterson devotee. I am not even familiar with most of what he has said. I just ran into that video on depression the other day by chance and agreed with some of what he happened to say in that one. Aside from that, all I know of him is his panic over SJWs that I've encountered in a podcast or two. Not my thing, really. -

Camera ObscuraVagabondSpectre, you are wasting your precious time. Hachem isn't interested in the truth, as it is apparently incompatible with what he wants to believe. He has an agenda that he is going to pursue no matter what. Beating your head against this wall is only going to give you a headache. I've encountered this type of person before. You will not make any progress with him. Walk away.

-

Proof that a men's rights movement is neededThis matter of that child support law seems rather simple to me. If you cause something to happen, you bear at least partial responsibility for it. Sex tends to cause births. If you have sex, you had better be ready to take responsibility for whatever might result from your action.

How does your lack of knowledge of something diminish your responsibility? Is it that you shouldn't have to pay if you aren't getting anything out of it, if you aren't allowed to participate in the child's life? Is it an exchange? Is your obligation to your children strictly a function of what you get out of your children?

If you don't want to potentially end up supporting a child, keep your sperm far away from any eggs. If you put your sperm near an egg, you have accepted the risk and should be made to bear the responsibility that truly belongs to you.

Suppose you start shooting large rocks with a powerful slingshot over buildings in random directions, not knowing where the rocks land. Now suppose that someone gets hit with one of those rocks and loses an eye and you know nothing about it. If some evidence surfaces later that connects you to this injury, should your previous ignorance of the damage you caused get you off the hook? I think not. You should be punished and made at the very least to pay as much as possible for any damages you caused.

Why is sex any different in this respect?

Too many men refuse to take responsibility for what results from their sexual activities. It reflects badly on all of us men.

If I were to be told to pay child support for a child proven to be mine, one that I had been previously unaware of, I would embrace that responsibility and more. And while I would be frustrated with the woman for not telling me sooner, I would think it right that I be made to pay. -

Authenticity and its ConstraintsInauthenticity, in large part, it seems to me, comes from caring too much about what other people think of us, whereupon we internalize and behave according to values that are not really our own, or which, perhaps, we even disagree with. It is a failure of courage, self-respect, and wholeness, even a kind of weak neediness. We don't act for the sake of the good, as we see it, but rather for the sake of the approval of others. Even the fear of homelessness or being a free-loader might well be rooted in the same fear of disapproval. A truly authentic person might not care that he is seen as a loser or whatever. He isn't playing that game. Here, the practical and physical problems of survival and comfort present the real difficulties. But he might not want to be homeless or a free-loader for other reasons, perhaps seeing it as wrong to become a burden to others, for one thing. Such a person might need to work hard to become self-employed somehow, earning money in way that is in accord with his values and doesn't damage his dignity.

Maybe the world makes it impossible for someone to thrive while really attempting to live their real, examined values. Such a person, in refusing to compromise what is good, and maybe dying in the process, lives a noble life, it seems to me. Such a person is a warrior and hero in the best possible sense!

Ultimately, I think that acting with real authenticity amounts to truly acting according to your conscience, regardless of the social or even physical consequences for yourself. If you really believe it isn't right to eat animals, but you have internalized all the judgments you see in the culture around you that ridicule vegetarians, and you eat meat accordingly, you are behaving inauthentically, and you'll be unhappy in this condition. You'll be disappointed in yourself. But that's not the reason you ought to live according to your conscience. You are especially inauthentic if you have gone so far as to convince yourself that you believe and feel as they do, when you really don't.

Inauthenticity is a matter of pushing your real voice down, probably so far that you don't even know that you have one. The real you is unconscious. You live, think, believe, value, and perhaps even feel as one does, as one is expected to in your culture, in ways that your parents, your spouse, your friends, the people on TV, or whatever, would approve of. It is not that it is impossible to be authentic while also gaining the approval of others. Quite the contrary, authentic people tend to be more interesting and are often charismatic and attract admiration. It is just that the approval of others shouldn't be what determines your behavior.

This idea that there is a "real you", deep down, prior to all conditioning and approval-seeking is troublesome and possibly wrong. It seems to me that it might be the case that everything that makes you a particular individual is conditioned by an environment, be it the environment in which your ancestors evolved, or the social environment in which you develop. But I suspect that this misses something.

I tend to think that ultimately, what we are at the deepest possible level is universal, and our highest will desires the best interests of all, and is pure love. To act from the place of the True, the Good, and the Beautiful is the highest and deepest authenticity. When speaking, speak the truth! When acting, do what is right! If it is ugly to you, don't engage in it! Create real value as you best see it with honest examination. It sounds trite, but make the world a better place.

All of this requires deep and constant examination of oneself and one's motivations. Some people might think that they are saying what they really believe to be true and might be mistaken about their own real beliefs. Half-unconsciously, they might be trying to look cool or something like that, or might still be trying to find the approval of someone in their life who saw things in that way, and so on. Do I really believe what I am thinking or saying, deep down?

What could be more authentic than the simple truth?

Inauthenticity can also be of a rebellious sort, where your actions are still a function of the opinions of others, even if it is an inverse function. An anti-conformist is just as inauthentic as a conformist. Your actions should be completely independent of the opinions of others and guided by something else, perhaps the dictates of reason or higher love.

As Socrates urged, don't worry yourself about what others might think or do to you. Just concern yourself with doing what is good as you best understand it. If it gets you killed, so be it. Few things involve more authenticity than acting courageously for the sake of the highest and most beautiful things in the face of threats to your life. These things, however, must not be those things that others have pressured you to value, but those things that you truly value, that lift your heart, the sorts of things that inspire you and give you some hope for humanity and the world when you see others do them, the things that make you suspect that there might be some good in this world after all.

In other words, as Gandhi said, "be the change that you wish to see in the world."

Really, it is just another way of talking about strength of character or integrity.

But perhaps all you really want is beer and pizza, or to rape and murder small children. If you examine it deeply though, what doing nothing but eating pizza and drinking beer, or raping and murdering children, really amounts to, is this what you really want for your life and the world? Does this lift your heart? Is this what you want your existence to mean? Aren't you going to be disappointed with yourself? Listen to that deep inner voice! Act to gain its approval! But take care to be sure that this isn't just a voice you've internalized from others! Search for your real voice!

Even searching for your authenticity is to practice authenticity.

Most of all, don't lie to yourself!

What I am talking about is not being brutally honest in a way that hurts others either. Part of acting authentically, I think you'll find, involves consideration of the well-being of others. Do I really think and feel that it would be a good thing to indulge myself and say this hurtful thing? You can withhold your views while remaining authentic when it wouldn't do any good to spout them. You just need to hold on to what is true and good and not be swayed by social pressure. Keep your own voice alive, at the very least, inside your own heart and mind. Share it when the situation calls for it and it would be of general benefit, serving the good and the true and the beautiful. Telling someone you think is ugly that they are ugly is definitely not what I am talking about. That involves a very crass idea of what it means to be devoted to truth and authenticity. It may be true, but doesn't saying it conflict with the higher demands of your conscience? Is it true that I think I ought to tell this person that I find them ugly? There are different levels in such an act. There is truth on some superficial level. But at a deeper level, to say that thing is also to act according to the belief that you ought to do this action. Behind that statement is another statement: "I believe that I ought to tell this person that they are ugly." Do you really believe that you ought to, or are you lying to yourself because you want to indulge some appetite for cruelty and power over others?

But if there is something you believe is true that you also truly believe that you ought to declare as true, then say it!

Deeply authentic acts are those that you'll never regret, that'll never bring a pang of conscience. Instead, they'll make your heart sing. And you'll be forever glad that you found the courage to do these things.

Ultimately, you are the judge of yourself. Nobody else can die in your place for you. Those people whose approval you act for will never take your burden of moral responsibility upon themselves. Act according to your real, examined values and you will find your own deep self-approval.

Few of us, if any, have the courage or strength of character to do this all the time. It is an ideal that we should aim for, however.

The trouble is discovering what it is that you truly value. This requires some honest and courageous examination.

I think all of this has something to do with why Socrates said that the unexamined life isn't worth living. Consider it. If you act all your life according to values that you don't really believe in, or according to no values at all, or actually against your values, of what value is your life to you, or to anyone else for that matter? And a little examination goes a long way. It is easy to see how empty the values of your culture often are. If you live according to them, you'll only find that same emptiness. -

The Conflict Between Science and Philosophy With Regards to TimeYes, I think technology does interfere with a proper appreciation of the natural world. It is sad that so many these days spend so much of their time texting rather than engaging with the world around them.

It is good that you explore the arts! There is much value to be found there.

As for Bergson, I haven't read more than just a tiny bit here and there. He has long been on my to-do list, but I have always felt a bit intimidated, as I have difficulty understanding what he is talking about when I do sample his work. I started to read one of his books several years ago and didn't get very far before something else grabbed my interest. But I will have to put more effort into his work one of these days! I would like, in particular, to understand his view of time.

As for Stephen Robbins, I watched the first video a week or so ago, which I saw mentioned on these forums somewhere, maybe by you. It seems interesting, but I am not sure I quite understand what he is trying to convey yet. I mean to watch more to see where his line of thought leads. I also have read part of his book, Time and Memory, and mean to finish it one of these days. Right now though, I am trying to finally tackle Kant's first critique, starting with some secondary introductory material and the Prolegomena. That reading project might take me a little while at my slow pace! -

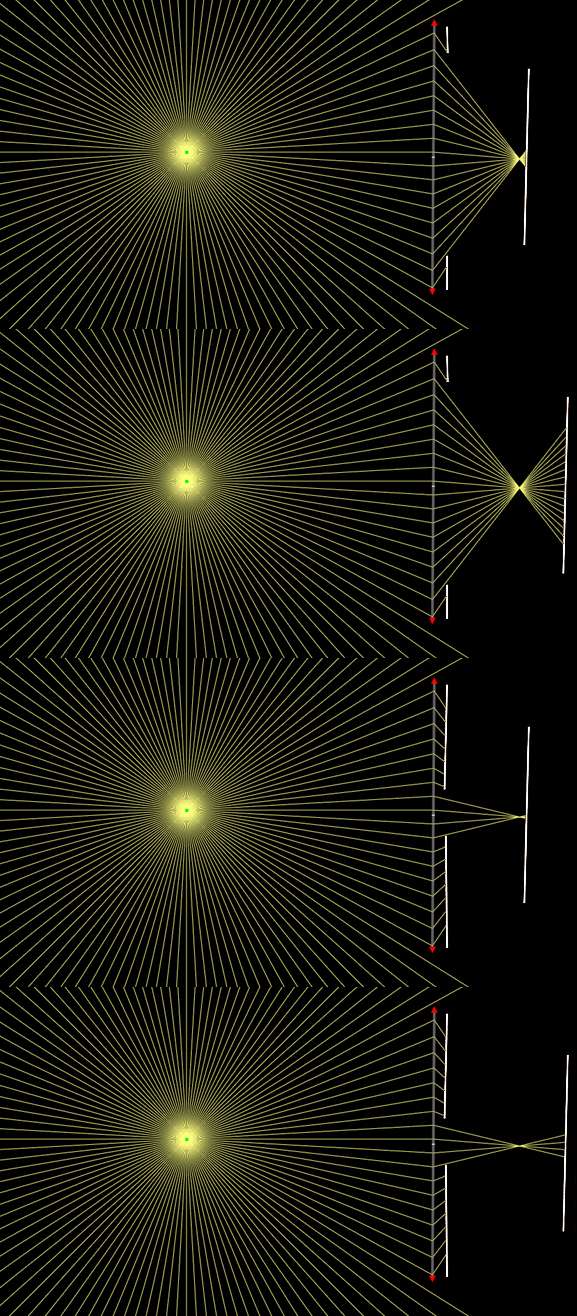

The Conflict Between Science and Philosophy With Regards to TimeOne of many baffling things about time involves the question of how quickly time passes and the idea that time cannot be its own evolution parameter. Let me explain.

Velocity is distance over time:

V=d/t

This means that as an interval of distance is covered, a certain amount of time passes. Let's say that the velocity is 10 miles per hour.

V= 10mi/1hr

Relating distance to time in this way works fine. But how quickly does time pass? If we try to express the rate of change of time this way, we seem to be trying to put time over time.

V=t/t

Time passes at 1 second per second or 1 hour per hour. This tells us nothing! And 10 hours over 10 hours equals 1 with no units, since the units cancel. No matter what time interval you plug in, you get this result. As you can see, time cannot be its own evolution parameter. It is as pointless as saying that there is one inch of distance in one inch of distance. But time does seem to pass at a finite rate! Notice that you don't experience your entire lifetime zipping by in a snap. You also don't experience it passing so slowly that it is almost stopped or actually stopped. You experience it passing at a certain rate. This rate might seem to vary a little as with time flying when you are having fun. That apparent variation isn't particularly interesting to me. What I am interested in is the strong experience that we have of time passing at a rate, even though this seems absurd when you think about it.

It might seem that the rate of time passage lies in something like the rate at which you are passing through a series of states. Instead of 1 second per second, you have 24 frames per second. But this solves nothing. Why does a second, which contains the experience of 24 frames, seem to pass at the particular rate it does? We are back to the problem we started with. This time that is passing outside the film strip that allows us to move with respect to it seems to pass at a certain rate.

Consider the following. With a film strip, we could have an animation of a moving dot and could mark our film frames with frame numbers standing for a kind of time unit. So the dot will change position from frame to frame at a certain rate with respect to the frame numbers. It might move at a rate of 1 millimeter per frame. But here, we still have no motion, real or apparent. It is just a static collection of frames. In order for you to move with respect to the film strip to see apparent motion in it, you need real time outside of the film strip. So now, as you move, you are passing through so many frames per second. You can keep doing this, removing yourself once, twice, three times, and so on, each time spatializing the time dimension. You could make another filmstrip depicting your dolly motion with respect to the first filmstrip, each frame containing an image of your dolly at a certain position along the strip. But in order to have change, you need to introduce another time dimension orthogonal to the previous one, this time real. And then you need to really move with respect to the strip. But how is this possible? Baffling and fascinating! -

The Conflict Between Science and Philosophy With Regards to TimeThanks!

If one stares at space, maybe as an artist, space appears to take on a new experience. Artists, such as the impressionists, or maybe Da Vinci saw in space what most cannot, because the skills have not been developed.

I am an artist of a somewhat traditional sort, doing mostly painting, drawing, and a little sculpture, and I have long been very interested in space. I like to look at arrangements in space that draw attention to the spaces between things, which make the space part of the composition. Unfortunately, painting can't really do this. I also love to hike, climb, and generally spend time in nature, especially up around and on top of big mountain peaks. And what often interests me most is just the sense of space and the arrangement of things in it. The big spaces around and between rocky peaks is impressive, but so is the space in a forest or crag or in and around a plant. Architecture often exhibits space nicely as well.

It is hard to explain just what it is that I find most interesting about space.

It seems that without any objects or landscape, if you were to inhabit a completely featureless, empty space, you wouldn't notice the space. You need intervals between things and to have depth perception and the ability to move around the scene to appreciate or to even have the experience of spatial depth.

I have no idea if I notice anything about space that others don't, but I usually get blank stares when I talk about how much I like to pay attention to the spaces between and around things, so perhaps you are right.

Even in two-dimensional arrangements, I find a great deal of interest and aesthetic feeling in even a single drawn line. The gestural quality, the relative intervals between prominent features, the dynamics of the curves, the texture, the varying intensity of the line, and so on, are all very worthy of contemplation and appreciation! I quite like looking at signatures!

I love time too, and am deeply fascinated by it. Arrangements in time are wonderful. Few things I have found give me bliss like playing a good hand drum, even though I am not terribly good at it! The better I get though, the more satisfying the experience becomes.

I find movement to be incredibly blissful. I live to engage with interesting, usually rocky, terrain and to bring my attention to what I am doing, to the spaces I am moving through, to the sense of change, and to make every action as deliberate, conscious, efficient, graceful, skillful, and quiet as possible. I tend to treat it like a Japanese tea ceremony. It isn't just the space and time that I appreciate in such activity, but also how energy behaves. I like to become conscious of gravity, momentum, friction, and so on, often visualizing changing force vectors, trying to fully appreciate how it is that I manage to find purchase on small footholds by utilizing oppositional pressure, by controlling the directions in which force vectors point by using momentum, and so on. The world and my body and perceptual apparatus become a thoroughly engaging toy!

Rock climbing is one of the most aesthetically pleasing things I have found in all my years. It brings together many of the things I most appreciate: space, time, movement, interesting physics, finesse, strength, the need for courage and mental fortitude, mindfulness, the symbolism of ascent, skill, puzzle-solving, effort, breathing, a Heideggerian sort of engagement with the environment and tools, interesting knots, sun and weather, all the many aesthetic qualities of natural stone, danger, pain, and so on. Yes, pain and strain! It's part of it! Pure bliss! By far the most beautiful sport there is, in my opinion! Underappreciated! And it's not merely a sport, but also an art and a form of spiritual practice! For some, it is religion!

The point of all this is that I am indeed a great lover of experienced space, time, and qualitative physics and I am also an artist and athlete. But, is this appreciation really rare? I am not so sure. I think that mechanics and mechanical engineers have a similar appreciation of how interacting machine parts relate in space and time, how forces operate, the qualitative aspects of the functioning of a well-functioning machine, the properties and interactions of the materials, and so on, all in space and time, even if they aren't conscious of it. Athletes of many sorts, I think, are sensitive to these things. Anyone who appreciates music, nature, or art probably has it. Dancers clearly do. Skilled drivers too. I suspect that it is a fairly universal feature of human experience. I have known a few though who seem to primarily have an intelligence and appreciation for all things related to language, and who seem to have deep deficits when it comes to space, time, and intuitive physics.

Even though science comes into play in much of this, science is blind to most of what I am gesturing at. Perhaps this is the space and time, not of scientists or philosophers, but of world-engaged aesthetes! And perhaps it is these who are most in touch with what space and time really are! It is like the difference between a scholar of love who doesn't love and one who loves deeply without a great deal of intellectual analysis. Who has the greater insight into the thing in question? I guess the different approaches to these things simply offer different kinds of insight.

I get so carried away! -

The Conflict Between Science and Philosophy With Regards to TimeIt seems to me that the conflict between what is being claimed in this thread to be time as conceived by scientists and time as conceived by philosophers relates to the whole problem of the objective versus the subjective. What is objective is scientifically verifiable. What is subjective is not. And the flow of time as we experience it is not objectively verifiable. Since science operationally only has access to the objective features of reality, it doesn't say anything about what we experience subjectively. Science ignores subjective time for the same reasons it is unable to adequately address the question of consciousness or subjective experience. But we all know that regardless of the fact that subjectivity cannot be objectively verified, it is nevertheless real. We know this directly. And we know exactly what it is, qualitatively, even though we can't explain it. I'd say that the same goes for time as qualitatively different from space and as something that passes, that gives us the experience of change.

The essential feature of experienced time is simply change. One thing gives way to another. There is a flow. Raise your hand and move it across your visual field. Right there, in that experience, is a mystery that science will never address.

The scientific view of time gives us a picture that doesn't give us any reason to expect an experience of change. The scientific view of time simply spatializes it. Imagine, for instance, a movie reel unrolled, the film stretched out flat on the floor. We tend to model time like this, events being spread across a spatial interval. But here, the events are simply adjacent. There is no real before or after. There is no causal dependency. There is no causality at all. Most importantly, there is no change. There is just a static set of events arranged in a sequence.

But isn't this spatialization of time just a convenient way for us to represent it in order for us to "picture" it? It allows us to draw graphs. But as usual, we should be careful that we aren't confusing the map for the territory. Real things have qualitative aspects that are not captured by simple quantity, that can't be carried by a variable in an equation. And we tend to forget that even a spatial interval as we experience it is more than a simple quantity. It isn't just a number. Like time, it has its own quality. And when we spatialize time, we are simply mapping the quantitative aspect of one qualitative feature of our experience onto another. It is essentially a lie. We are taking what is not simultaneous, what is temporally sequential, and what is not necessarily visible or visual at all, and rearranging it in our experience so that we can see it visually, and so that we can see it all at once (ignoring that we must take time to take it all in with a bunch of eye saccades). It is no wonder that our representations tend to lead us into confusions about time.