-

Philosophy talk dot org(*psst*, Whenever I come across someone elsewhere that seems genuinely cool — including people I disagree with mind you — then I point them over here, but don't tell anyone *sshh*) :)

-

Non-necessity (modal logic) and God (theism)I suppose, then, as far as assertions go, there's a mutually exclusive choice between 1 and a,b:

- 1. Among possible worlds some are without sentience. Sentience is not necessary.

- a. Definition: G is necessary.

b. Definition: G is necessarily sentient.

The former (1) might be exemplified by some simple worlds while assuming they're non-contradictory, whereas the latter (a, b) assumes G and consistency.

OK, let me try being a bit more concise...

Possible worlds semantics at a glance:

• necessarily p ⇔ for all logical worlds w, p holds for w

• □p ⇔ ∀w∈W p

• possibly p ⇔ for some logical world w, p holds for w

• ◊p ⇔ ∃w∈W p

So, a logical world is an inclusive, complement-free entirety where ordinary logic holds.

Let's just say this is ordinary logic (catering for intuitionist/constructive logic), the three first in particular:

1. identity, x = x, p ⇔ p

2. non-contradiction, ¬(p ∧ ¬p)

3. the excluded middle, p ∨ ¬p

4. double negation introduction, p ⇒ ¬¬p

5. modus ponens

6. modus tollens

Ontology and logic tend to meet at identity. -

Non-necessity (modal logic) and God (theism)@Terrapin Station, I just meant that obviously you can deny 1 as follows:

a. definition: G is necessary

b. definition: G is necessarily sentient

c. ... sentience is present for all logically possible worlds ...

d. 1 is wrong

And some do just that, albeit contrary to Swinburne.

My line of thinking was that it seems rather odd to assert G, and deny 1 on that account, when much simpler worlds come through as non-contradictory.

@unenlightened, I think @Terrapin Station has the notion of "possible world" well illustrated.

A logical world is an all-inclusive, complement-free entirety (all, "everything") where ordinary logic holds.

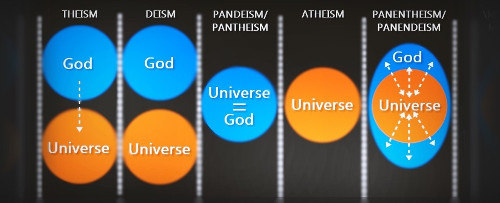

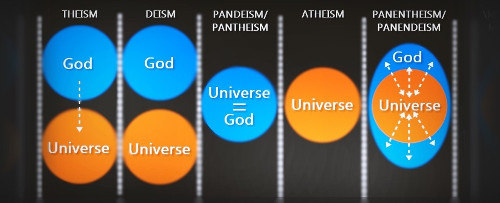

Like in the illustration, the whole deism column is a suggestion of a possible world (God and Universe). -

Non-necessity (modal logic) and God (theism)If one believes that God's existence is necessary for any possible world [one] would think that a world that consists solely of a single simple that's not God is impossible. — Terrapin Station

Right, yet that's just a definitional petitio principii.

By assertion a world without sentience is impossible because G is absent therefrom, because G is necessary (by definition), which, by the way, holds for any G.

I actually think that a world with a single "zero-dimensional thing" is incoherent, by the way, and I'm an atheist. That's simply because I don't believe that there can be zero-dimensional things. — Terrapin Station

For worlds like ours, by a physical/epistemic/nomological assessment, I tend to agree (no two-dimensional superstrings either per se).

Metaphysically, maybe, maybe not.

Logically it seems non-contradictory to me.

(It was just a (very) simple example that came to mind; not the best.) :) -

Non-necessity (modal logic) and God (theism)Claiming God's existence and solipsism is such a strange combination. — Emptyheady

Good point (I suppose, unless the solipsist consider themselves God).

Perhaps subjective idealism, à la Berkeley or something similar, is a better example.

Or panpsychism of some sort, one that starts from a particular sentiment already contrary to 1.

Come to think of it, if the argument above is sound, then it would seem contrary to Plantinga's modal ontological argument.

Anyway, in this context, I'd say 1 (the zero-dimensional "thing", for example) is significantly more plausible than the contrary. -

Non-necessity (modal logic) and God (theism)What does it mean to say that God is sentient? If it has any meaning at all it clearly cannot be sentience as we know it. And even if it were it seems an awfully big leap from every possible world has a sentient being involved in some kind of a relationship with it to all possible worlds have sentience and further still to all possible worlds are sentient. — Barry Etheridge

Well, defining sentience in terms of something else is perhaps somewhat futile.

I'm thinking it's part of mind, where mind is an umbrella term for self-awareness, consciousness, thinking, feelings, phenomenological experiences, qualia, the usual.

Let's just say "sentience" as we know it, since, what else would we be talking about...?

I suppose we might come up with some special kind of "sentience", but then we're already starting to move into the thick fog of London on a dark night, a bit like inventing things for the occasion. :)

(Sometimes I've seen sentience referring to an awareness of one's own sentiments, feelings, reactions and such, as distinct characteristics of oneself, quite close to self-awareness, something along those lines, but that may not be spot on.) -

Non-necessity (modal logic) and God (theism)Anyway, someone who believed that God's existence is necessary would think that the first premise is false. — Terrapin Station

Sure, but that's a tad bit presumptuous, implausibly strong, unjustified, especially in comparison to any number of alternatives.

Consider a rather simple world consisting in one zero-dimensional "thing", that's indivisible, and changeless, and that's about it. Can you derive a contradiction from that? Not particularly interesting, but seemingly consistent nonetheless.

I'm finding this one hard to make sense of. Why should God 'carry' sentience to all possible worlds? God creates a possible world consisting of, say, a piano, and not much else. Why does the piano have to be sentient? It looks as though there is the assumption of immanence??? — unenlightened

That's not quite how possible worlds semantics work.

A possible world is an inclusive entirety, where ordinary logic holds. Here are some suggestions, e.g. deism (ignore the simplicity, it's just for illustration):

A significantly simpler suggestion is the zero-dimensional "thing" above, which does not need sentience (or sentient entities) to be logically consistent, non-contradictory. -

Non-necessity (modal logic) and God (theism)At a glance, I see a couple objections:

- outright reject modal logic

- solipsism, panpsychism (or some other special idealism)

It's trivial to come up with an idealist objection.

Suppose I'm a solipsist, holding that only whatever I'm certain of is the case (thereby conflating epistemology and ontology). My error-free knowledge extends roughly to the existence of (self)awareness and some (other) experiences, including sentience (perhaps depending a bit on what's understood by the term). Regardless of any modalities, my sentience becomes necessary.

It's already broadly agreed upon that solipsism is not deductively dis/provable. My self-awareness is essentially indexical, and noumena to any other (self)awarenesses. Phenomenological experiences themselves are "private", part of onto/logical self-identity and not something else.

So, there's no dis/proof to be found here, though obviously such sentiments has consequences that most folk find ridiculous, but there you have it, that's one objection.

Does a necessary God, that's necessarily sentient, imply idealism (well, or substance dualism or whatever)? -

What are you listening to right now?Yep, remember this. Not the concert in person, but the rest. The sentiment of "fuck you, you, and you.". Damn, how boring and mellow I've become.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cBojbjoMttI -

What are you listening to right now?Sinner, where ya gonna run to?

Regardless of the superstitious nonsense, Simone gives an impressive musical (and felt) performance. The only "power" is the music itself. Such is music, and Simone's got it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QH3Fx41Jpl4 -

Problem with Christianity and Islam?Some emotional responses here. Maybe I should have posted it over in the sociology section. Of course killing infants is repugnant, as held by most believers and others alike. :)

There's a fairly simple observation involved.

Remove the Christianity and Islam part, and go by common religious beliefs, like taught in Sunday school and madrasas, for example.

1. It's uncontroversial among such believers that an infant (or other innocent child) that dies, goes to heaven, to be with God. I'd say this often enough includes accredited pastors and imams and such, although "heaven", "God", "innocent", etc, can be subject to all manner of ideation and definitions.

2. If an infant is killed, then the killer has committed a crime, both by various religious and secular rules. Those entertaining faith as per above — the killer in particular — may believe the killer can still be "saved", others may believe they cannot and don't care (or perhaps believe they're damned in any case), yet others may believe something else, who knows.

As per such faith, killing an infant will secure the infant's entrance into heaven, to be with God. Believers, be they (would-be) killers or not, commonly share 1 above.

That does not mean the act of killing is good or anything — it goes against other rules — yet, the repercussions extend just to the killer, not the victim.

It's not so much about consequentialism, as it is about believed consequences of an infant's (or other innocent child's) death. Neither is it about throwing Abrahamic religions in the bin. It's about analyzing real-life beliefs, irrespective of any (perceived) controversy.

Anyway, have a good weekend, and holidays. -

What are you listening to right now?I can't watch this in the UK due to copyright, hope you can where you are. — Punshhh

Blocker here, but here's a live performance, that's not blocked here at least (Canada, per se):

https://youtu.be/XPpCRAQdkDU -

What are you listening to right now?Beat this. Well, Mozart perhaps, but contemporary (no, Satriany doesn't quite measure up). Amazing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U5Vki76x-EU -

Problem with Christianity and Islam?Doing evil in order to achieve the good is not justified in Christianity and Islam, generally speaking. — ThorongilEVEN if you believed that it was permissible to kill an infant to gain the benefits of heaven for the victim, you would still be held responsible for the infant's(s') death and would likely be punished severely. — Bitter Crank

Right.

And so, going by such faiths, presumably the killer ends up down below, and the infant up high.

Or something.

There is no alleged policy in the supposedly blesséd imaginary hereafter that justifies any action in the only world we actually know anything about. As far as we know, beneficial and harmful consequences for any action are limited to this present world. — Bitter Crank

:D

As an aside, euthanasia has come up in the public in recent years.

The context here is mostly the "right to die" and "assisted suicide" movements. -

Problem with Christianity and Islam?Let me repeat: nowhere have I claimed it permissible.

On a satirical note, here's The Onion on the topic: God Angrily Clarifies 'Don't Kill' Rule -

Problem with Christianity and Islam?It is you who thinks it is permissible. — Πετροκότσυφας

I do not.

Consequences of breaching "permissible" extends to the killer alone in this case (surely not the infant).

Consequences to the infant (if the answer is "yes") is heaven and eternal bliss with God. -

Problem with Christianity and Islam?, you're hand-waving.

It's not about definitions, but about what people believe.

In case you answer "yes" to the question, you've affirmed the killer's goal. -

Problem with Christianity and Islam?Let's say that the answer is yes (whatever this thing you call "heaven" is). What does this have to do with the murder of an innocent child? — Πετροκότσυφας

As per above:

while going by said tenets, the reasoning itself is sound, and the killers accomplished the goal — jorndoe

... of which there are examples.

Note, though, it's not me calling it "heaven". It's part of the faith system. How much sense does it make? -

Problem with Christianity and Islam?This addresses none of my points, though. — Πετροκότσυφας

There's a simple question involved, going by said faiths:

If an innocent child is killed, then will they go to heaven? -

Problem with Christianity and Islam?I lean towards the views of Peter Singer. Infanticide, despite its scary-sounding verbage, is probably not morally problematic because infants aren't even capable of futural thoughts or even are conscious. To say that it is morally wrong to take the life of a young infant is, in my opinion, probably unfounded equivocation. — darthbarracuda

Going by the tenets, the argument extends somewhat beyond infant age.

Might go by some notion of innocence, or mortal sin or other passage to hell.

(It all seems rather arbitrary in any case.) -

Problem with Christianity and Islam?Around 200 children have been killed as collateral damage in US drone strikes on Pakistan in the last ten years. I don't recall the moral justification for this in the Founding Fathers' words of self-constitution. These are actual deaths, not imaginary ideologically-inspired deaths. — mcdoodle

As an aside, ISIS have displaced 100,000s of children. :(

The examples in the opening post are not imaginary deaths.

Anyway, children are easy victims.

- Attorney: Woman thought God told her to kill sons (CNN; Mar 2004)

- The Numbers Are Staggering: U.S. Is 'World Leader' in Child Poverty (Paul Buchheit; AlterNet; Apr 2015)

-

Problem with Christianity and Islam?Not sure how much there is to define. The tenets are just common beliefs, like taught in Sunday school.

The creeds further maintain that Jesus bodily ascended into heaven, where he reigns with God the Father in the unity of the Holy Spirit, and that he will return to judge the living and the dead and grant eternal life to his followers. — Christianity (Wikipedia article)- Source: Christianity (Wikipedia article)

Muslims view heaven as a place of joy and bliss, with Qurʼanic references describing its features and the physical pleasures to come. — Islam (Wikipedia article)- Source: Islam (Wikipedia article)

-

Problem with Christianity and Islam?Which are the basic tenets you are referring to? — Πετροκότσυφας

Very basic... Heaven (bliss with God), hell, innocent children, eternal souls, ...

Hinduism (or some flavors thereof) is different if memory serves. -

Religious experience has rendered atheism null and void to meHe sees no difference in kind between the biblical account of the past and how we came to be, and the scientific account. — dukkha

Ehm...

Suppose I was to proudly proclaim "there was snow on the peak of Mount Everest last Wednesday localtime". What, then, would it take for my claim to hold? Why that would be existence of snow up there back then of course, regardless of what you or I may (or may not) think.

Certainty and knowledge are not the same. (For some proposition, p, certainty that p means you'd also have to know that you know p, ad infinitum.) The hard part of epistemology is justification. And with all the problems (induction, the diallelus, biases, etc) a strong methodology/standard is required.

Science is fallible model → evidence convergence; empirical, self-critical, bias-minimizing. The convergence methodologies are commonly inductive, but deductive reasoning is of course used.

Does your relativization of science also extend to medicine (and your family doctor)? -

Religious experience has rendered atheism null and void to meHow dare they! There ought to be an inquisition! — Wayfarer

By Jove, no. Already had some. Big mistake. :)

Apologists are busy trying to marrying science and religion; some theists are busy trying to deny evolution (and whatever else they don't like) when they find it incompatible with their theism.

You guys are like a room full of puppy's. — Punshhh

"Why, you stuck-up, half-witted, scruffy-looking nerf herder!" :)

It's quite simple. You see that Colin has had mental health issues, so he must be delusional. — Punshhh

No, not (necessarily) delusional; I personally know people of a whole variety of outlooks, that are just ordinary folks.

Conversely, I'm not going to lie, or encourage/reinforce any. -

Religious experience has rendered atheism null and void to meArkady No, what Dawkins should do, is realise that whether God exists or not, is not a matter for science. It's really very simple. — Wayfarer

Isn't that what apologists try to do?

Quoting your Catholics link, underline emphasis mine:

Fr. Spitzer is a Catholic Priest in the Jesuit order (Society of Jesus) and is currently the President of the Magis Center and the Spitzer Center. Magis Center produces documentaries, books, high school curricula, adult-education curricula, and new media materials to show the close connection between faith and reason in contemporary astrophysics, philosophy, and the historical study of the New Testament. Magis Center provides rational responses to false, but popular, secular myths.

Some theologians seems to be trying to marry up science. -

Religious experience has rendered atheism null and void to meIf you understand that 'creation mythology' is just that - mythology - then the fact that it didn't literally occur has practically zero bearing on the religious account. — Wayfarer

Sure, but it does have impact.

- ‘He had to die,’ accused mother tells police in son’s killing

- Coverage of the Kimberly Lucas case

- Pastor's wife dressed her three daughters in white 'before stabbing two so they could meet Jesus for the end of the world'

- Mom kills son believing boy would be better off in heaven

But why take the lives of innocent children?

[...]

Moreover, if we believe, as I do, that God’s grace is extended to those who die in infancy or as small children, the death of these children was actually their salvation. We are so wedded to an earthly, naturalistic perspective that we forget that those who die are happy to quit this earth for heaven’s incomparable joy. Therefore, God does these children no wrong in taking their lives. — William Lane Craig- Source: Slaughter of the Canaanites (Reasonable Faith; Aug 2007)

A doctrinal problem with Christianity and Islam?

1. killing an infant should give the infant safe passage to heaven

2. so the killer would be doing a major self sacrifice ("thou shall not kill"), for the sake of the infant

3. the killer did a selfless act to save someone else

4. the killer did good (we can assume the infant was at no time in pain)

5. you ought kill infants, sending them off to eternal bliss, saved (might even be a win-win)

The dark side of Pascal's Wager? You know, just a matter of being on the safe side?

And this is just one class of examples. -

Religious experience has rendered atheism null and void to me@Hanover, since you seem a staunch proponent of the cosmological argument, I hereby invite you to partake in the discussion:

http://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/487/the-kalamcosmological-argument-pros-and-cons/ -

Religious experience has rendered atheism null and void to mePresumably you haven't experienced God as Colin has, or you wouldn't be bothering to write this. — Punshhh

In my experience many have had epic experiences (including me). :)

I can't tell what colin's experiences were, though.

And I continue to experience them, even this afternoon at church. I was so overwhelmed by what I was experiencing I had to fight back tears throughout. — colinThis is a feeling I can't really put into words — colinI think it's quite simply magic. — colin

Except, strongly emotional it seems. -

Religious experience has rendered atheism null and void to meGood to hear that you're feeling well, colin.

The expressed certainty ought to warrant some caution and some attempt to minimize bias, though; especially since what you claim implicitly applies equally to everyone (and more or less literally everything, for that matter).

Recall, purely phenomenological experiences are part of the experiencer, not something else. That's also the reason there's no such thing as telepathy, and why these "special" experiences are private.

if anything significant differentiates perception and hallucination, then it must be the perceived — Searle (paraphrased)

Personal revelations are notoriously incompatible and incoherent, yet sometimes engender making quite extraordinary (or universal) claims. Say, if someone claimed they were abducted by aliens, would you then take their word for it (you might think they were lying or being honest about their belief alike)?

We already know that some kinds of experiences can be induced by a variety of simple means. We also know that mere inwards self-examination has inherent limits. We're hardly perfect perception-organisms (and cats jump at shadows).

I suppose relevant questions might include if these experiences directly influence your decision-making and social interaction? And why you think there's a personified (extra-self) being of sorts involved? How did these experiences inform you, and of what...? (Have you honestly given other options a chance? Compared them with your current thinking? Perhaps spoken with various other people?) -

An argument that an infinite past is impossibleA modern version of this argument is used to show the Big Bang could never have happened. If eternal Time exists (in big-T Newtonian dimensional fashion), then there would have had to have been an infinite amount of time elapsing before - suddenly, in a bright flash - our Universe got created. So therefore never enough time could pass to arrive at that point.

A better answer is that the Big Bang was the start of time, as well as space. So we can't think of the pre-Bang as a temporal dimension - except in some far simpler metaphysical sense yet to be articulated scientifically. — apokrisis

Right. I guess contemporary cosmology will have it that temporality is an aspect of the universe. So, where causation (among others) is temporal, causation is also an aspect of the universe.

Anyway, it seems to me the principle of sufficient reason is hiding somewhere. That is, if the universe has a definite age, then a sufficient reason is sought for this particular age. If the universe does not have a definite age, then it would have to be infinite or "edge-free".

I've come across a few logical/deductive arguments that the universe cannot be temporally infinite, and others that it must be. :) At closer inspection it seems none of them hold, though. -

An argument that an infinite past is impossibleWhen in trouble, when in doubt, run in circles, scream and shout! — wuliheron

:D

Will Donna Summer (1977) do? -

An argument that an infinite past is impossibleI'd be interested in any objections to the objections, that hence finds this peculiar argument (deductively) sound.

-

An argument that an infinite past is impossibletime is continuous — Metaphysician Undercover

Maybe.

I don't think the argument intended zero-dimensional "moments", or a particular quantification, as such.

It was given to me in a much less formal format; it's also possible my rendition remains a bit hokey. :) -

An argument that an infinite past is impossibleA quick observation:

If we argue from Big Bang models, i.e. extrapolate to a definite earliest time, then other infinites just show up instead, infinite density and temperature.

Temperature may be a better label than time for the evolution of the universe

Perhaps time is the wrong marker.

Perhaps what we call time is merely a labeling convention, one that happens to correspond to something more fundamental.

The scale factor, which is related to the temperature of the universe, could be such a quantity.

In our standard solutions, the scale factor, and hence the temperature, is not a steady function of cosmic time.

Intervals marked by equal changes in the temperature will correspond to very different intervals of cosmic time.

In units of this temperature time, the elapsed interval, that is, the change in temperature, from recombination till the present is less than the elapsed change from the beginning to the end of the lepton epoch.

As an extreme example, if we push temperature time all the way to the big bang, the temperature goes to infinity when cosmic time goes to zero.

In temperature units, the big bang is in the infinite past!

In an open universe, the temperature drops to zero at infinite cosmic time, and temperature and cosmic time always travel in opposite directions.

In a closed universe, on the other hand, there is an infinite temperature time in the future, at some finite cosmic time.

A closed universe also has the property, not shared by the open or flat universe, of being finite in both cosmic time and in space.

In this case, the beginning and end of the universe are nothing special, just two events in the four-geometry.

Some cosmologists have argued for this picture on aesthetic grounds; but as we have seen, such a picture lacks observational support, and has no particular theoretical justification other than its pleasing symmetry.

If we are looking for clues to a physical basis for the flow of time, however, perhaps we are on the right track with temperature. — Foundations of Modern Cosmology by John F Hawley and Katherine A Holcomb

The no-boundary hypotheses do not have any of these, but are sometimes dismissed as counter-intuitive. -

An argument that an infinite past is impossibleHere are some bad/good (nonsensical) things about it — andrewk

I apologize for any poor wording. :)

Let me try adding details, some of which go one way, others another:

1. if the universe was temporally infinite, then there was no 1st moment

2. if there was no 1st moment, but just some moment, then there was no 2nd moment

3. if there was no 2nd moment, but just some other moment, then there was no 3rd moment

4. ... and so on and so forth ...

5. if there was no 2nd last moment, then there would be no now

6. since now exists, we started out wrong, i.e. the universe is not temporally infinite

As before

- items 1,2,3 refer to non-indexical moments (1st, 2nd, 3rd), but 5 is indexical (2nd last, now), which is masked by 4

- 6 is a non sequitur because the argument only shows that, in case of an infinite past, now does not have a specific, definite number (1st, 2nd, 3rd, ..., now)

-

An argument that an infinite past is impossibleThere are some extrapolating arguments from evidence that the universe was not temporally infinite (e.g. Big Bang models, entropy, the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem).

These may vary a bit on the no-boundary hypotheses.

I was mostly interested in the logical argument here.

If someone shows that anything but a definite earliest time is impossible, well, then that's the most rational scientific pursuit, for example.

Personally, I think there are better arguments by intuitive appeal (I can post some if anyone's interested).

Seems to me the argument isn't sound.

these days arguments of the impossibility of an infinite past are only made by people that do not understand mathematics well — andrewk

Yep, especially for logical arguments.

jorndoe

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum