-

What would you do in this situation?

Possible scenarios of a better world are themselves evidence of better quality lives. By the standards of the possible world, we live "worse" (by some standard that has yet to be established) lives. I can always imagine a world with where I have more money, or another friend, or a higher status, and so on. Again, just because I am not in the top 1% of earners in the United States does not mean my life is not worth living. Likewise, just because there is some future scenario where the top 1% of earners living better quality lives than the current top 1% of earners does not mean the current top 1% do not lead lives worth living.

So, either you must argue all lives below perfection are of poor quality because, by the evidence of the possible perfect world, we live poorer quality lives than we might have, or you have to accept that possibly creating poor quality lives is on the table. -

What would you do in this situation?Your argument is bad. It does not follow from the existence of a better possible world that the current one is not worth living in.

-

On the practical application of natural rightsI'm not exactly sure where to start my critique, because pretty much the entire thing is questionable or, at least, needs further clarification. Where would you like to start:

1. The metaphysical assumptions regarding human nature.

2. Self-defense.

3. The hierarchy of rights.

4. Social collusion and tension.

5. Federalism and the issue of rights. -

Is western culture completely incompatible with daily life?I disagree with your assessment of western culture not valuing productive jobs. If, by "western culture," you mean "artwork and similar media," you might have an argument there, as that is a common theme in a good amount of art we see. However, if you use "western culture" in a broader sense, in the sense that includes more than art, but the lifestyles and ideals of the society, I think the opposite is true. There is an extreme amount of social pressure to do something "productive" in society; usually, this is because "productive" fields are in higher demand than "unproductive" fields, so they pay better and are seen as more financially stable, thus making them "smart" choices. Tell people you are going for a degree to become a doctor, engineer, lawyer, businessperson, corporate scientist, or similar job and expect a lot of smiles and follow up questions about particulars (what do you want to with that). Tell people you are going for a degree to become an artist, philosopher, sociologist, or something similar and watch as polite people's eyes slightly unfocus as they try to think of a way to carry on the conversation, while not so polite people ask questions like "what are you going to do with that?"

Even how we talk to each other reveals how much we value work and what you do. When meeting someone new, one of the first questions you ask them is some permutation of "what do you do for a living?" I would not be surprised if it is the next one most people say after "what is your name?" Most of the art produced that champions the "unproductive" fields and aspects of life is a reflection of western culture's job-focused obsession. It resonates with people particularly because they feel their jobs are oppressive and boring. The artist is seen as free and above the concerns of this job cycle, doing what they want to do, much like the viewer of a story about an artist struggling to make it and eventually succeeding wishes they could do. Think of the movie "Office Space." The conclusion and final speech of the movie is that practically no one likes their job, so you find something you can tolerate and go from there. Do you think the majority of people working right now enjoy their jobs or even get any type of fulfillment other than the money and social status that comes with it?

The reason we do not talk about "productive" topics to be consistent (whatever that means) is for a multitude of reasons. First, work is draining. We already spend a vast majority of our time doing things we do not really want to, so why would anyone want to spend their free time doing work outside of work if they do not have to? Second, as mentioned, these topics tend to be uninteresting, so talking about them with most people will not be socially productive. Third, a lot of topics that are important to discuss can turn into a can of worms. Talking about anything related to politics, philosophy, religion, economics, and such can turn nice talk into anything ranging from awkward to angry. You learn not talk to anyone about these topics rather quickly. Fourth, people probably do not have knowledge on the topics, so discussions tend to exclude one or both of the parties. I love philosophy, but there are topics I do not know about, so when people talk about these topics, I do not have anything to discuss, so I avoid these discussions. Lastly, and this is most important, pragmatically, I do not see how people with no real working knowledge of a subject discussing and working on the subject aids in its progress. For example, robotics may be important, but most people have no idea on how AI works, let alone on a level required to talk about robotics. At best, you have people talking about weird hypothetical scenarios with no pragmatic basis. At worst, you get people who think they know how to progress, but have no idea how nonsensical their ideas really are. -

Transgenderism and Sports

Yeah, I don't really get the division in that one. I've heard that the reason they want to have women's only events is to attract women into the sport. In other words, it is more about publicity and to show women in chess, not so much that women cannot compete with men. Most of the big tournaments are open to both genders. -

On the practical application of natural rightsFurther question: you put freedom of choice in possessions under the secondary category, but put property in the tertiary category. There is a tension here, as having possessions in the first place requires the ability to own property. If I do not have property, then how can I have choice in property? Is this simply saying that while I am free to choose different property to own, there is no guarantee that I can exercise this right?

-

On the practical application of natural rightsQuestion of clarification. Does the right to life include things such as health care and environmental policies aimed at mitigating the effects of pollution on the health of the population?

-

Hamilton versus Jefferson

Thank you for answering. I now understand your exact position. I admit you did answer them, though I believe the spacing of the posts and the massive amount of text that was disconnected form those posts created issues. If I may critique your posting style, I find that the text you cite from stuff you previously wrote can make things seem like you are talking at us, not with us, if that makes any sense. I know writing out everything again is a pain, but at least try to edit out the sections a bit more and explain how it a applies a bit better.

I am interested in the topic and wish to continue discussing it. Two questions:

1. Is the right to life a positive right or a negative right (or something else, like a right that requires both negative and positive duties)? In other words, per the right to life, do I have to only not take actions to harm and kill others, or do I have to take actions to preserve and support life?

2. If the right to life is unalienable, and if the conceptus, no matter the circumstances, has a right to life, how could some individual states decide that? I agree with what one of the earlier posters said- if the right to life is unalienable and nothing can overcome this right, then the right cannot be waived just because the conceptus is the result of rape, has a mental/physical deformity (to do so would say those with disabilities have less of a right to life), and other such cases. -

Islam: More Violent?

But the idea of a religion being at odds with practices other than the religion is nothing new; the secular law not based in the religion is just an extension of that line of thought. It's not like Judaism did not have a long list of divinely inspired laws that the population was to follow, lest they suffer punishment and misfortune. I am saying that the even if Augustine specifically was attacking the current secular law and its unique basis, the notion of religion trumping other ideological concerns is not unique.

Also, I question how much Christianity had to do with the Roman empire collapsing. I have no reason to believe it was significant, at least not any more significant than all the other problems Rome faced. We face the issue of "correlation versus causation": one could say Christianity weakened Roman culture, or one could say that the collapse and political turmoil of the Roman Empire led people to turn to a religion that promised life in another world. I also have heard issues with the "Dark Ages" moniker, claiming that it is more of a propaganda phrase used to villianize Christian authority at the time. The spread of ideas and philosophy seems to have halted, but this might have been a slowing in travel because of political/economic reasons, not necessarily that nothing of note was going on. -

Hamilton versus Jefferson

Where did you answer the question about how your version of natural rights applies to viability as the definition of personhood? The "we are all created equal" part? You have to answer the specific questions and show how your answer applies to them. How you answered those questions is not clear. -

Islam: More Violent?Last time I checked, agreeing with Augustine was not a core component of the Christian faith. The notion of the religious law of god overcoming the secular is not exactly unique to any religion. Neither is that the world is inherently evil and, at its core, it cannot be saved. The issue people have with your connection between Augustine and radical Islam is that you do not actually demonstrate Islam got these ideas from Augustine. The best you have is that Muhammad was living in an area with Christians in it (some of these might have been heretical, as I believe the Christians that took in Muslims early in the faith were). Further, I would not call Augustine Christian doctrine, but a Christian idea. What you are left with is "Radical Islam and an influential Christian thinker share the common idea that their religion is good and the rest of the world, without adherence to their religion, is bad."

-

Artificial Super intelligence will destroy every thing good in life and that is a good thing.Paragraphs are useful to make text easier to read. Sorry, it is really hard to read, especially on my phone.

-

Hamilton versus JeffersonNo, natural rights are definitely inalienable. There is no way of separating them from consideration of one person or another, they have to apply to everyone. Therefore, once a fetus reaches the age of 21 weeks and 5 days, at which point it can live independent of the mother, it must be accorded natural rights. — ernestm

If we are to assign rights that are inalienable, then the federal-state distinction is nonsensical, as it means a large governing body can take your rights away. The fact that it is called "California" and is relatively smaller than the entire U.S. does not change what is going on. To my knowledge, for a good portion of U.S. history, the rights in federal documents (Bill of Rights) were only applicable on the federal level, meaning that they were not guaranteed on the state level.

My purpose of bringing up abortions under the case of pregnancy from rape is to illustrate an issue: even if personhood does apply, it does not automatically follow that the right to life always supersedes the right of other's liberty. If I was hooked up on a life support machine by a third party to an innocent, ill person in order to help keep that person alive, I do not think the state or any person can demand that I remain hooked up to this person, even if it means his death. I cannot have the entirety of my liberty and freedom sacrificed to save a life. This, again, returns to economic concepts. There are actions the government can talk- regulations, increasing taxes on certain industries, increasing taxes to pay for programs- that will save lives. We know this. It does not follow from this that the state must implement those programs to the point of the act utilitarian's dreams.

This, of course, assumes that the conceptus is a person in the legal sense, as well as the moral sense, both of which can be doubted (or, at least, doubted enough to create problems for the pro-life side). -

Are there philosopher kings?

I think you are missing my point. My point is that everyone thinks that they are the special one who "gets" it. They get the world and how it works. Further, they think everyone else (sans a small group of people that the person is a part of) misses the mark and has fallen. Everyone fancies themselves the philosopher king, or, at least, better than the masses (and, yes, this applies to the people like myself).

However, everyone has psychological pitfalls that they fall into regarding their beliefs. Sometimes, they are obvious in some people: people who hold their beliefs with a cult-like attitude. However, everyone has these pitfalls and everyone falls into them; if you say you do not, you are lying. So, yes, it might be true that some people have problems properly examining issues. They might need help and easing to overcome and get around their psychological hurdles, and some may be effectively closed off from external human interference and nothing we can do can change that. However, everyone has the potential to overcome their hurdles and reach something much better.

Of course, there are probably people who are naturally more intelligent then others, but we have no way of knowing the scope of this, so it is kind of moot point to discuss. -

Hamilton versus Jefferson

Abortion is like every act of potentially immoral killing- it needs to be dealt with on its own. Simply calling it murder and the opposition an echo chamber is not exactly productive.

Even if abortion is immoral, it appears that a young girl who is raped into pregnancy who then decides to have an abortion is not blameworthy. There is nothing necessarily good in this case (though we can argue about that), there is nothing necessarily wrong either. Even if there is, it seems the two options: force a young girl to carry a pregnancy that was the result of rape, or allow an abortion, the abortion seems like the lesser of the two evils. Yes, it might be logically consistent to hold no abortions except in the case of adverse health effects, but it is also logically consistent to say, "lying is always wrong, regardless of the circumstances." Being that act utilitarian who kills innocent people gain one more unit of utility over not killing them is logically consistent. Peter Singer might be logically consistent when he says that moral status of personhood does not really happen in the conceptus until two years old when they start forming conscious desires, but I doubt you think of his theory as good for that.

This appears especially true in the political. Effectively, it is an overstepping of the state to say that teenage girls must carry a pregnancy from rape to term. The conception of "right to life" does not automatically trump "right to liberty". The state cannot force excessive and insane tax rates on you and the economy just because it saves a statistical life (and there are a lot of laws and policies that can be put into place that do just that). In fact, I think there might be a bit of the right to life and the right to liberty because simply existing in and of itself may not be very good. The right to life appears to cover more than just surviving- it means also having a life to live. The state cannot ruin the liberty of its citizens to the point where we seriously begin to question whether the right to life is being preserved.

As an aside, whether you like it or not, most people, even those against abortion, claim abortion is morally permissible in the case of rape. I believe that Ronald Dworkin and thinkers like him used this notion as a springboard, using it to try and reexamine why we intuitively find abortion moral in some cases and abortion immoral in others. -

Hamilton versus Jefferson

So, can the state (governing body) just dictate that women cannot have abortions unless their health is severely threatened? In other words, could all 50 states have a policy that automatically rejects abortions on the grounds of rape and incest? -

Hamilton versus Jefferson

Would, under your interpretation of the Constitution, the state be able to force women who are pregnant as a result of rape or incest to carry their pregnancy to term?

Also, to all members of the discussion, are we referring to natural law in regards to a moral theory or natural law as a legal theory? -

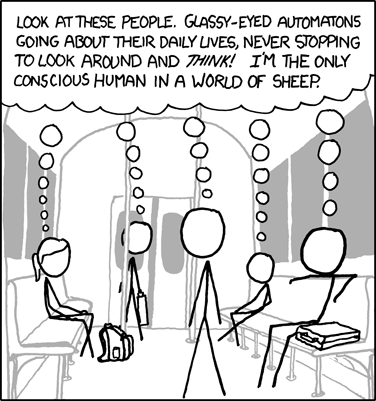

Are there philosopher kings?Whenever people talk about philosopher kings or only an elect number of people having access to hidden knowledge, I think of this comic:

-

Technological Hivemind

It is irrelevant. Even if it was hedonistic pleasure or some other utilitarian related ethics, your hive mind is akin to a utility monster. Even if the hive mind produces more net utility (which is arguable), the option is pretty much death for all who enter it, so it is no different then telling everyone to kill themselves by jumping into the maw of the utility monster. Again, if it requires sacrificing everything in the world to create a world no one in the world has a part of, the action is effectively immoral. -

Are there philosopher kings?

I get that vibe, but I wonder if it is more to do with all the popularity surrounding him and his style of writing (dialogue between characters). -

Technological Hivemind

You didn't get the argument then. If the hive mind is one puree mind, then joining it is, for all practical purposes, like death. I might as well kill myself because there is no benefit to me.

If the hive mind is not a puree mind and I just gain the ability to reflexively percieve everyone else's thoughts and feelings, then it is arguably not a uptopia or even may be a distopia. Ignoring how we would respond to, say, a person with chronic depression all the time and other such issues, I don't think we actually want this. I don't want everyone to know what I'm thinking and feeling at all times, particularly if it involves them. I don't think I actually want to know what other people think of my thoughts and I. I think there is a good chance most of us repulsed by one another.

You are trying to present this as a Nozick experience machine related thought experiment, but it is not clear that this hive mind is a utility machine. -

Technological Hivemind

The individual who would produced would be so far off from me that I might as well just kill myself. I would not benefit from the exchange if it becomes a complete hive mind, in the sense that my individuality is overridden.

If my individuality is maintained (i.e. I have a constant, reflexive perception on people's feelings and thoughts of everyone at once), then I wouldn't want everyone to know what I was thinking and feeling, and I wouldn't want to know their thoughts and feelings. Again, it's nice to fantasize and know if your partner really loves you in a deep way, or know if your boss likes you. But I would never want the power always on and the ability to turn it on and off always there.

I don't think this would be a utopia. It sounds rather bad. -

Technological HivemindYou really do not want this. At all. I can understand the benefits, but we can get most of those without actually getting a hive mind. Not to mention loss of individuality and loss of mental privacy, the one place you have to yourself. And do you really want to know what other people think of you? I mean, it would be nice once in a while: does he really love me? Did she commit the murder? But constantly knowing what others think of me based on outward appearances is bad enough, let alone what they'll judge in my thoughts.

-

Islam: More Violent?I think we are missing the mark on the issue. We can argue all day about the merits and interpretations of Islamic texts and traditions. However, I think this is like arguing about Christian or Jewish texts. Yes, they endorsed behavior and morals we find wrong, but the Christian and Jew have an interpretation that allows them to, at least, embrace an interpretation of the texts that is compatible with modern liberal states (or, those who are incompatible with the state, are fringe minorities). The main questions, in regards to Islam, are:

What are the radical doctrines? What are these demographics, particularly among Muslims in Western countries or our direct allies? What are the moderate doctrines? What are their demographics? How good of a shot do they have in expanding? How long will it take the moderates to expand substaintially enough to gain power and be able to maintain it? Most importantly, what are the rest of us going to do in the meantime? -

Explanation requires causation

Not to get side-tracked because this argument is different from the one in the OP, but I do not understand how that deals with Hume's argument. If we justify induction via induction, then we are engaging in circular reasoning. We have to appeal to some other reason to justify induction. -

Explanation requires causation

I thought one of Hume's big arguments was to say induction could not be supported as a valid way of reasoning to knowledge because its justification was circular (if I remember epistemology correctly). -

Exorcising a Christian Notion of God

Like the Platonic conception of good, we can understand it in a very real sense, but there is still a lot we do not understand. We may come to understand it one day, but in our current state, we do not.

Also, as I said in the initial thread regarding the evil god concept, the skeptical theist may admit that the argument holds weight. Even then, I wonder about the parallel actually holding. I can imagine a world where there is more evil and there is the potential for hope more easily than a world with free will and less moral evil. -

Exorcising a Christian Notion of GodEternal hell doesn't square with a perfectly good God.

The Calvinists make a good point about free will. How can God be sovereign and not in control of where people end up for eternity? You can't have it both ways.

Their problem is that the then have to reconcile the perfect good with God predestining who is damned. — Marchesk

I'm going to defend some smarter Calvinists, and not the ones like Fred Phelps. I'm going to avoid all the theological reasons the Calvinist may have (certain Bible verses can point to some type of elect) in favor of philosophical ones.

Calvinists might have a different conception of good then most people. They are probably of the divine command theory of good. They think all goodness is found, by its very nature and definition, in God. What we consider good might be very different from its actuality. Think of the allegory in the cave: the good we see is a shadow, and only through the light can we possibly understand good. Even though the Calvinist would claim to see some goodness, they would claim that the goodness is ultimately in God, of whom we cannot ultimately understand.

Also, most of them are probably some form of free will compatibilist- they think that the free will that gives us moral responsibility exists and this free will is compatible with determinism. Everything is preordained, but this preordination does not conflict with the moral responsibility necessary to send one to hell. -

How did living organisms come to be?

Actually, the space within objects may be expanding, just on a level and rate so low that we do not notice it. I'm not a physicist though, so I have no clue. -

Explanation requires causationI have not read Hume, but what he may be arguing is that all the causes we see may not be causes at all. He is not claiming that there are no causes; he is only claiming- for the sake of skepticism's purposes and particularly with regards to induction- we cannot go from "I see causation" to "causation is real."

Furthermore, a habit is not necessarily a cause. For example, Hume (I believe) stated that he has a habit of seeing things in a causal way in day-to-day life, and he definitely wrote more than on just skepticism, so he clearly used causation even as a philosopher. However, as a skeptic, he may acknowledge that certain causal events in his perception may not be causation, but only an association between correlated events. In other words, he is not caused to see causation, he just has a tendency to do so. If habits were causes, then they would have complete control over the individual and determinism would follow. However, Hume does not seem to be using "habit" in this way. Like someone who smokes, the form a habit of smoking. The may really feel compelled to smoke and do so regularly, but it is not impossible to break the habit, nor is it impossible for the smoker to temporarily stop the habit in certain moments. -

Islam: More Violent?I was being rational. Sensible Muslims avoid taking moral lessons from questionable verses in the Bible as much as sensible Christians do. — Baden

Again, I do not think this is how it works with Christians. The Christian merely has a theological framework that allows them to maintain the stance "Slavery is wrong; I oppose slavery" and "my holybook endorsed slavery for the Isrealites and doesn't really say anything negative about slavery in the New Testament." Unless they can state "certain sections of the Bible are fallacious"- a position that is too strong for the vast majority of Christians- Christians must be able to maintain the verses inside their texts as being true.

The same is for Muslims. -

Islam: More Violent?IFor example. To save people from slavery, it was necessary to convince Christians that the verses from the Bible that encourage slavery are immoral, in order to prevent them from using their religion as a justification for slavery. — tom

That's seems like an oversimplification of what happened. Modern Christians still look at the Bible now and have to find ways of justifying those verses. Often, you will hear some version of "that was under the old covenant, we are under the new covenant," or "slavery back of antiquity was vastly different from the slavery of today or the slavery of 19th century America." It is similiar to the Old Testament genocides: they cannot be deemed immoral, so they have to somehow be explained into a coherent picture of theology that allows them to say "genocides we see today are immoral." The slavery verses themselves are practically never deemed immoral; the Christian merely has a different way of interpreting them or a theological way of avoiding a commitment to slavery practiced in their societies.

The other big issue is that the people pushing for the abolition of slavery were Christians in some shape or form, or, at the very least, were well within the Western cultural society. Needless to say, the abolitionists were well emplaced within the Christian societies at the time. Though they might have been considered outsiders by the circles supporting slavery, they were not so far outsiders that they could not partake inside the culture effectively.

Furthermore, at least in the United States, it is not as if the pro slavery Christians were convinced by the force of argument to abandon their slaves. They started a war, fought for four years, then were placed under military watch until 1877. We have no idea when the pro-slavery crowd became a fringe minority and racism took over; I doubt that most Southerners would not mind returning to slavery in 1877.

This is to all, and not just tom-

In order to combat radical Islam, we have to have acknowledge three things:

1) Muslims need an avenue that allows them to mantain their faith and interpret their holy texts in such a way that it is practically compatible with modern Western morality. I doubt we will get everything (much like how many Christians are against abortion and gay marriage), but at least things like equality of women and some of the more violent practices. I have no idea how to do this.

2) The promoters of said interpretations need to come from within Muslim communities and have a way to influence the intellectual and social culture of said communities.

3) We have to accept that the only way to stop radical Islam in some cases is through force and conflict. Said force and conflict will probably be costly and come over a long span of time. Again, the opposing side must come from within the community and cannot really be the primary work of an outsider, like the United States. -

How did living organisms come to be?

This answer is currently unknown. For example, the argument you give for why it could not be hydrogen particles is faulty. Just because we cannot replicate something in a lab right now does not entail that we can never do it. Even if we humans can never practically do it (it requires a level of resources and precision that humans just cannot replicate), that does not mean that it is impossible and never happened.

Even statements like, "Before the Big Bang, there was nothing," are dubious. The singularity in the Big Bang model, to my understanding, is simply the point where our current models and understandings breakdown and cease to function. There may be something beyond the Big Bang, but we have no way of knowing this right now. -

Do you want God to exist?

You appear to cut off in your post, but I think you are asking: how could we support and/or prove the premises or show the premises to be false? Well, that depends on the particular argument. Do you honestly want to go through them all?

The original point of bringing up the ontological argument is that we argue over them, but their soundness and validity would indicate the god of classical theism is real, as their entire point is to show the god of classical theism exists a priori. In other words, we can possibly use reason alone to show the god of classical theism exists. -

Do you want God to exist?

The same way any other argument works: the premises are all true and the conclusion follows from the premises. If one of the premises is highly questionable or the argument is invalid, then the argument fails.

There is no reason that "properly basic" beliefs have to be intersubjectively corroborated. I would say that perception is often "properly basic" to epistemology- if you cannot defend perception in any meaningful way as having any connection to reality, then the major thrust and purpose of epistemology is lost. At best, you might be able to get away with some general "armchair thinking" stuff, but that remains a dubious point. By the very nature of perception, it is subjective. This goes back to my point: not all good epistemic reasons are convincing reasons. My perceptions of me not committing a murder are good epistemic reasons for me to say, "I did not commit this murder," even if I acknowledge that, from a third-person perspective, the evidence looks like I committed the murder. Even if a jury would most likely convict me in a court of law based on the evidence, I would still be justified in believing that I did not convict the murder, all else being equal. -

Do you want God to exist?

The fact that it is arguable and that no one can agree on whether God exists or not is the basis of the OP's point. For example, if one of the ontological arguments work, it would show that such a being does exist.

I would also like to point out that this entire argument has a great deal to do with epistemology. For example, if Alvin Plantiga is right about his epistemology, then the common religious experience of God is properly basic belief, and, by extension, God is based in properly basic belief and is justified for the faithful. Other epistemologies would label a god concept without positive warrant to be, at best, irrelevant, and, at worst, effectively shown to be false. -

Do you want God to exist?I think the idea of God this OP is attempting to address is the first, and I think belief, in this context, is not predominately determined by purely rational thought, but rather than by convention, emotional need and in general by psychological, rather than logical, influences. — John

The OP stated the god concept they were discussing was the god of classical theism: your omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent variety. This definitely falls under the second category, though most of its defenders fall into the first category. -

Do you want God to exist?

I do not need to discuss my views on the question of theism, as my ideas on the subject are irrelevant to the truth of yours.

I have presented an analogy to explain why disagreement that cannot be resolved does not automatically entail that one side of the party is unjustified in their belief. I have explained that not all good reasons for belief are convincing reasons. I have explained why the idea of desire is not sufficient to explain the theist-atheist divide. The notion of atheists who desire some type of god seems to fly in the face of this idea, especially given the known psychological mechanisms would seek to eliminate the weakest and least important belief to psychological coherence- in this case, whatever irks them about God. This does not discuss intuition, faith, religious experience, being justified in false beliefs, believing things for bad reasons, and a bunch of other factors. Desire alone does not cut it; a detailed explanation of the psychological nature of belief formation would do it, but that is pretty much true of any belief formation. Simply put, the reasons for belief in God or lack thereof need to be taken are extremely varied; any attempt to put it down to a single issue or cause will be as faulty as trying to put down a single cause for the responses to, "Why do I like or not like New York City." -

Do you want God to exist?Well, my logic is simple.

There are two parties engaged in debate - theists and atheists. As fate would have it they both inhabit the same world. Yet, they come to antipodal conclusions. In a way, pitifully, their simulataneous existence is sufficient proof that both sides have got it wrong - they simply can't convince each other even when they throw their very best arguments at each other. Am I then mistaken in concluding that there's something else that's driving people into theism and atheism? — TheMadFool

There are two parties engaged in debate - believers in space lizards and disbelievers . As fate would have it they both inhabit the same world. Yet, they come to antipodal conclusions. In a way, pitifully, their simulataneous existence is sufficient proof that both sides have got it wrong - they simply can't convince each other even when they throw their very best arguments at each other. Am I then mistaken in concluding that there's something else that's driving people into pro-space lizard and anti-space lizard?

Obviously, it does not follow from mere disagreement that both sides ought to embrace agnosticism. Again, good reasons for belief may not be convincing reasons for belief. Also, I agree that there is more going on than fear and pure logic when it comes to theism and atheism. I disagree that it all comes down to desire. This clearly is not the case, as you would not find atheists who wished theism is true otherwise.

Chany

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum