-

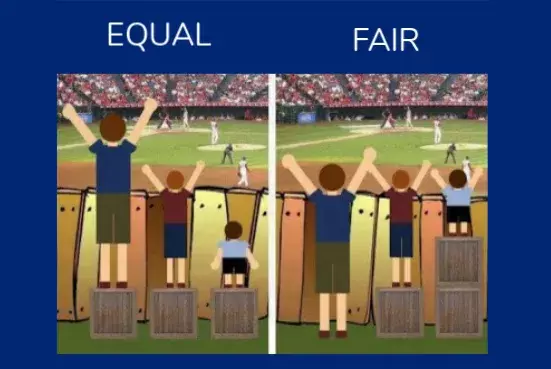

Is the real world fair and just?

How does it make sense to ask which of these is closest to thermodynamic equilibrium? -

Is the real world fair and just?Fairness is not something

youwe come across in the world.

It's somethingyouwe do in the world.

(Edited for ) -

Gödel's ontological proof of GodImagine that some intelligent, all powerful, all knowing, creator of the universe actually does exist, but that because it doesn't necessarily exist then we refuse to call it God, as if the name we give it is what matters. — Michael

"Q"?

-

Gödel's ontological proof of GodIf it is not necessary that Q, then it is not possible that is necessary that Q. — TonesInDeepFreeze

I bet you are fun at parties :wink:

Note that god is by all accounts necessary. Hence, a contingent god is not god. If it is not necessary that there is a god, then, as you say, it is not possible that it is necessary that there is a god...

Hence, if it is not necessary that there is a god, then there is no god.

This by way of setting out what is at stake for the theist - it's all or nothing.

(edit: hence, where Q is god, if it is not necessary that Q, then it is not possible that Q). -

Gödel's ontological proof of GodS5 does not say that pQ -> nQ. — TonesInDeepFreeze

It does say that ◊□p → □p. Hence if ~□p, it follows that ~◊□p.

If god is not necessary, then god is not possible. If god is not necessary, then god is not god.

While the coffee here is not strong enough, it does seem to me that if the ontological argument fails then there is something contradictory in the notion of god. God cannot be just possible. A contingent god is not god. -

Gödel's ontological proof of GodIf, in S5, if god is possible then god is necessary, Gödel's ontological proof shows that god is not possible in S5.

Not what the Op wanted. :wink: -

My understanding of moralsThere's something oddly inconsistent in the implicit claim that we ought not expect others to follow any moral precept.

How is that not, thereby, itself a moral precept?

The pretence of stepping outside moral discourse in order to discuss moral discourse is exposed. -

My understanding of morals:smirk:

I don't think you are wrong. But I do think what you have said is incomplete.

As is what I have said.

Edit: Do you also read Master Kong? -

My understanding of morals

Well, not entirely. Sometimes it also depends on what others want.That depends entirely on what you want. — Vera Mont -

My understanding of morals:roll:

Given a choice of extremes, must we always choose the one or the other? No, we can reject both, accepting the complexity of our situation. -

My understanding of moralsI should add that of course there is some truth in the OP. Much of morality is about coercive control. And why shouldn't you do what you want? A question that should be taken seriously.

Appealing to a mythical "intrinsic nature" denies that we each exist only in a community. To a large extent it's an appeal to the American Myth of Rugged Individualism, the very same myth that denies its citizens a decent health care and social security system and brings us Trump and other sociopathic billionaires.

And for all that, the question of what to do remains. -

My understanding of morals

Well, no. It's pieces from p.207 and §258 of Philosophical Investigations. It's not Kripke. It's pretty much straight Wittgenstein. All I did was change "sensation" to "intrinsic nature".This is pretty much Kripkenstein. — frank

The point is the obvious one that if we take as the only criteria for what is right, what seems right to each of us, then we have stoped talking about what is right and changed the topic to what we want.

That does not address, let alone solve, the problem of what is right.

Notice the difference between "Think for yourself" and "Follow your intrinsic nature". "Thinking for yourself" allows for consideration of others. "Follow your intrinsic nature" drops consideration from the agenda.

The notion that we have a "deepest essence" is deeply problematic, especially after "existence precedes essence".

The Op doesn't address what we ought to do. -

My understanding of moralsAs for my own understanding, I don't need to satisfy you. Or Banno. — T Clark

The level of awareness espoused in this thread is that of the eight-year-old decrying "you're not the boss of me!".

Sure. But when you grow up you might choose to act with some consideration for others. -

My understanding of moralsOn intrinsic nature.

The temptation to say "I see it like this", pointing to the same thing for "it" and "this". Always get rid of the idea of the private intrinsic nature in this way: assume that it constantly changes, but that you do not notice the change because your memory constantly deceives you.

Let us imagine the following case. I want to write about my intrinsic nature. To this end I associate my intrinsic nature with the sign "S" ——I will remark first of all that a definition of the sign cannot be formulated.—But still I can give myself a kind of ostensive definition.—How? Can I point to my intrinsic nature? Not in the ordinary sense. But I speak, or write the sign down, and at the same time I concentrate my attention on my intrinsic nature — and so, as it were, point to it inwardly.—But what is this ceremony for? For that is all it seems to be! A definition surely serves to establish the meaning of a sign.—Well, that is done precisely by the concentrating of my attention; for in this way I impress on myself the connexion between the sign and the sensation.—But "I impress it on myself" can only mean: this process brings it about that I remember the connexion right in the future. But in the present case I have no criterion of correctness. One would like to say: whatever is going to seem right to me is right. And that only means that here we can't talk about 'right'.

(Paraphrasing Investigations). -

Mathematical truth is not orderly but highly chaoticAny readable proof of Cantor's Theorem will contain at most a finite number of characters. Yet it

showscan be used to show* that there arenumberssets* with a cardinality greater than ℵ0.

And we are faced again with the difference between what is said and what is shown.

So will we count the number of grammatical strings a natural language can produce, and count that as limiting what can be - what word will we choose - rendered? That seems somehow insufficient.

And here I might venture to use rendered as including both what can be said and what must instead be shown.

Somehow, despite consisting of a finite number of characters, both mathematics and English allow us to discuss transfinite issues. We understand more than is in the literal text; we understand from the ellipses that we are to carry on in the same way... And so on.

But further, we have a way of taking the rules and turning them on their heads, as Davidson shows in "A nice derangement of epitaphs". Much of the development of maths happens by doing just that, breaking the conventions.

Sometimes we follow the rules, sometimes we break them. No conclusion here, just a few notes.

* just for @ssu -

Mathematical truth is not orderly but highly chaotic

Nicely phrase. Our new chum is propounding much more than is supported by the maths. Here and elsewhere....there's less there than meets the eye. — fishfry -

AssangeJournalism is not a crime, and Evan went to Russia to do his job as a reporter —risking his safety to shine the light of truth on Russia’s brutal aggression against Ukraine. Shortly after his wholly unjust and illegal detention, he drafted a letter to his family from prison, writing: “I am not losing hope.”

...we will continue to stand strong against all those who seek to attack the press or target journalists—the pillars of free society. — Biden

Hmm. -

Mathematical truth is not orderly but highly chaotic

Sure. What this argument purports to show is that a natural language has no fixed cardinality. And this is what we might expect, if natural language includes the whole of mathematics and hence transfinite arithmetic.For natural language to be uncountable, you must find a sentence that cannot be added to the list. To that effect, you would need some kind of second-order diagonal argument. — Tarskian

But the point is that "...the collection of all properties that can be expressed or described by language is only countably infinite because there is only a countably infinite collection of expressions" appears misguided, and at the least needs a better argument.

Your posts sometimes take maths just a little further than it can defensibly go.

Not I, but Langendoen and Postal. If you wish you can take up the argument, I'm not wed to it, I'll not defend it here. I've only cited it to show that the case is not so closed as might be supposed from the Yanofsky piece. Just by way of fairness, Pullum and Scholz argue against assuming that natural languages are even infinite.I didn't completely follow what you're doing, but in taking the powerset of a countably infinite set, you are creating an uncountable one. There aren't uncountably many words or phrases or strings possible in a natural language, if you agree that a natural language consists of a collection of finite-length strings made from at an most countably infinite alphabet. I think this might be a flaw in your argument, where you're introducing an uncountable set. — fishfry

Langendoen and Postal do not agree that "a natural language consists of a collection of finite-length strings".

Does mathematics also "consists of a collection of finite-length strings made from an at most countably infinite alphabet"?

Also, doesn't English (or any other natural language) encompass mathematics? It's not that clear how, and perhaps even that, maths is distinct from natural language.

All of which might show that the issues here are complex, requiring care and clarity. There's enough here for dozens of threads. -

Mathematical truth is not orderly but highly chaotic

You seem to have missed the argument presented. It shows that such a list would have no fixed cardinality.

Ok. -

Mathematical truth is not orderly but highly chaoticWhy should we suppose that natural languages are only countably infinite?

Consider:

A convolute argument, perhaps, but it shows that one must do more than simply assert that natural languages are at most countably infinite. Yanofsky must argue his case. " ...the collection of all properties that can be expressed or described by language is only countably infinite because there is only a countably infinite collection of expressions" begs the question. Indeed, the argument above shows it to be questionable.1. Let L be the NL English.

2. The set S0 is contained in L, where

S0= {Babar is happy; I know that Babar is happy; I know that I know that Babar is happy; . . .}

3. S1 may be constructed as follows

a. Form the set of all subsets of S0, P(S0).

b. For each element B in P(S0), form the sentence that is the coordinate conjunction of all the sentences in B.

c. Let S1 be the collection of all sentences formed in (3b).

S1 = {Babar is happy; I know that' Babar is happy; I know that I know that Babar is happy; ... ; Babar is happy and I know that Babar is happy; Babar is happy and I know that I know that Babar is happy;... ;Babar is happy, I know that Babar is happy, and I know that I know that Babar is happy;...}

4. S0 is denumerable, but S1, which is equinumerous with P(S0) is not denumerable (by Cantor's Theorem).

5. S2, S3, etc., can be constructed analogously. Each successive S has a greater transfinite cardinality than the one preceding it.

6. All of the S collections are contained within L.

7. L has no fixed cardinality. — The Vastness of Natural Language

There is something very odd about an argument, in a natural language, that claims to place limits on what can be expressed in natural languages. -

Can the existence of God be proved?"You might very well think that; I couldn't possibly comment"

See also https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ontological-arguments/#Gdel , and the concluding observations. -

Can the existence of God be proved?

Well,

looks a bit... overstated.PA is a chaotic complex system without initial conditions. — Tarskian

Aren't these the "initial conditions"...? These are the Peano axioms:

- Zero is a natural number.

- Every natural number has a successor in the natural numbers.

- Zero is not the successor of any natural number.

- If the successor of two natural numbers is the same, then the two original numbers are the same.

- If a set contains zero and the successor of every number is in the set, then the set contains the natural numbers.

I'm not following Tarskian's argument at all.

@TonesInDeepFreeze? -

Can the existence of God be proved?

Faith requires belief despite the evidence. Evidence is the Devil's doing.Accepting a truth without evidence is faith. Therefore, an axiom represents faith. — Tarskian -

Is death bad for the person that dies?Of course one consideration is the quality of the life one misses in being dead. Hence euthanasia. Death is not always undesirable.

-

Morality must be fundamentally concerned with experience, not principle.

Consider this list of actions performed on a football field.

1. Player A kicks the ball from the half to Player B.

2. Player B kicks the ball to player C.

3. Player C kicks the ball into the net.

It lists the individual acts of three people. Notice that it does not include scoring a goal. These acts might by chance be performed on a field by a group of people utterly unfamiliar with the rules of soccer, in which case it would be very odd to claim that they were playing soccer. In order for the act of kicking the ball into the net to count as the act of scoring a goal, something more is needed:

4. In a game of soccer, the act of kicking the ball into the goal counts as scoring a goal.

Scoring a goal is not reducible to an act by a single individual. It requires the act to take place as a part of the communal activity of playing a game.

All we do is move our bodies. But it does not follow that all actions are only bodily actions, and hence that all our actions are individual actions. Consider Davidson's classic example: flicking the switch, turning on the light, alerting the burglar. Alerting the burglar is not a bodily action. Or consider Anscombe's mass murderer, hand-pumping poison into the well. We would not accept as a defence: "All my acts are bodily motions, so all I was doing was moving my arm up and down, not poisoning the well!" Consider also the structure of our social world - this piece of paper only counts as money if we say so as a community; this piece of land is your property only if your neighbours agree; The very words you use only have meaning within the community in which you participate. The list is endless.

Hmm. Virtue ethics is slightly preferred amongst professional philosophers. Deontology has a small lead amongst those who specialise in ethics. I don't know how you might have gauged it's "popularity" more generally. Quite a few folk would be happy with an ethic based on flourishing, as part of a community, through self-improvement.But I also do not have much experience with it (Virtue ethics) due to its lack of popularity in modern times. — Ourora Aureis

I think I showed this not to be the case, since differing principles will lead to different actions, and hence have quite different results. A rational being will choose their principles on that basis.All independent principles have equal rational basis. — Ourora Aureis

I quite agree. An example is not a definition. You say we ought avoid making use of principles, yet apparently advocate a principle something like "One should act to maximise one's experience". Odd, that.A principle is not simply a consistency. — Ourora Aureis

Anyway, I don't know your background, but perhaps these comments might point you towards things you may not have considered. Philosophy is not easy. Cheers. -

Flies, Fly-bottles, and PhilosophyInteresting that you cite the paper in which Floyd argues that Wittgenstein had a much better grasp of Gödel than is often supposed.

And there is this:The underlying point of Wittgenstein's remarks on Godel is the underlying theme of the later Wittgenstein as a whole: our sentences do not carry their meaning with them intrinsically, or in virtue of something present to the mind ahead of, or apart from, how we give it expression in particular cases. Rather, what we can clearly say about what we mean or think can be made sense of only from within the context of some practice, or ongoing system of use. — Juliet Floyd

I suspect that we might maintain his constructivism, but perhaps rescind his finitism in the light of the considerations of rule-following found in PI.A mathematician is bound to be horrified by my mathematical comments, since he has always been trained to avoid indulging in thoughts and doubts of the kind I develop. He has learned to regard them as something contemptible and… he has acquired a revulsion from them as infantile. That is to say, I trot out all the problems that a child learning arithmetic, etc., finds difficult, the problems that education represses without solving. I say to those repressed doubts: you are quite correct, go on asking, demand clarification! (PG 381, 1932) — Quoted in SEP article

Don't these terms - “Truth”, “Knowledge”, or “Free Will” - already have uses and meanings? So to my favourite quote form Austin:...philosophers are inventing what these terms ought to mean. — Richard B

First, words are our tools, and, as a minimum, we should use clean tools: we should know what we mean and what we do not, and we must forearm ourselves against the traps that language sets us. Secondly, words are not (except in their own little corner) facts or things: we need therefore to prise them off the world, to hold them apart from and against it, so that we can realize their inadequacies and arbitrariness, and can re-look at the world without blinkers. Thirdly, and more hopefully, our common stock of words embodies all the distinctions men have found worth drawing, and the connexions they have found worth making, in the lifetimes of many generations: these surely are likely to be more sound, since they have stood up to the long test of the survival of the fittest, and more subtle, at least in all ordinary and reasonably practical matters, than any that you or I are likely to think up in our arm-chairs of an afternoon—the most favoured alternative method. (Austin, J. L. “A Plea for Excuses: The Presidential Address”, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 1957: 181–182)

Austin and Ayer had differing opinions on various topics. -

Morality must be fundamentally concerned with experience, not principle.

That is a contentious issue, as I've pointed out.You refer to cooperative actions that require multiple individuals but these can always be broken down into their individual parts, and us as individual beings have no control over the actions of other beings. — Ourora Aureis

An individual can kick a ball into a net; but can't score a goal. Scoring a goal requires that they be participating in the social activity of playing a game. Playing such a game, it has been argued, is more than just the sum of the actions of individuals, just a scoring a goal is more than just kicking a ball into a net. See the article linked previously for more on this. If you are going to maintain your assertion, you might want to address it's critique.

Again, sociology is about how people do indeed interact, but ethics about how they ought interact. These are quite distinct topics.Part of sociology is the study of human social behaviour, if your definition of ethics refers to how people relate to each other, then that's just sociology. — Ourora Aureis

Not particularly, although ethics is as much about what others ought do as it is about what you or I should do. My preference is virtue ethics, although deontology and consequentialism have their place. "Principles", your term, also have their place - acting consistently, keeping one's word, and so on. You claim that "one can easy construct an anti-principle and yet it has the same effect in a moral framework", which seems quite puzzling. Acting consistently will have a very different outcome to acting inconsistently; not keeping your word will bring about a very different response from others to keeping your word, and so on. All principles are very much not in effect the same as all others.Your view of ethics seems to be about forcing principles upon others. — Ourora Aureis

A shame that you sense hostility. You are of course not under any obligation to reply. The issues I have raised are substantial, not mere wordplay, but you may prefer not to address them. -

Morality must be fundamentally concerned with experience, not principle.Sociology only tells us what we have done. Ethics is about what we do next. Ethics is not about how the world is, but what we should do about it.

Sometimes "just a semantic difference" means "I hadn't considered that". -

Morality must be fundamentally concerned with experience, not principle.I dont believe there is a difference fundamentally between aesthetics and ethics, as in the preference for orange juice is equivalent to a serial killers preference for murder, theres no distinction just preferences. — Ourora Aureis

Hmm. A preference for orange juice does not have the same impact on others as a preference for murder. Again, ethics is about how we relate to others. There is a difference between considering what you prefer and considering what others prefer. There is a difference between "I will only drink orange juice!" and "You will only drink orange juice!".

That's somewhat contentious:Because actions can only be committed by individuals... — Ourora Aureis

Visiting the Taj Mahal together looks to be something that fundamentally you cannot do individually. And visiting the Taj Mahal together is only one of many acts that require collective intentionality.Suppose you intend to visit the Taj Mahal tomorrow, and I intend to visit the Taj Mahal tomorrow. This does not make it the case that we intend to visit the Taj Mahal together. If I know about your plan, I may express (or refer to) our intention in the form “we intend to visit the Taj Mahal tomorrow”. But this does not imply anything collective about our intentions. Even if knowledge about our plan is common, mutual, or open between us, my intention and your intention may still be purely individual. For us to intend to visit the Taj Mahal together is something different. — SEP: Collective Intentionality

What I wanted to draw your attention to is that ethics is not about experience so much as about action, especially actions involving others. In that regard your OP says very little about ethics. Might leave you to it. -

Morality must be fundamentally concerned with experience, not principle.

There seems to be something oddly passive in supposing that ethics be based on experience. As if you were nothing but an observer.

Ethics and aesthetics are not about how things are, but about what we do. In science we look around to see how things are, in aesthetics and ethics we look around to see how we ought change how things are.

Choosing an orange juice for yourself is neither here nor there, while choosing an orange Juice for everyone is an ethical act.

It's what you do, not what you experience, that marks ethics and aesthetics, and defines the logic in use.

Ethics is fundamentally concerned with actions, not principles or experience.

Egoism is mistaking what you want for how you should deal with others. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

Sure.It's more the latter though, right? — Count Timothy von Icarus

I agree. "RRBGGGRWW" gives a neat compression of the image.I think this is an area where information theory gives us a very good set of tools for understanding this sort of thing. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Provided one has the context in which to unpack it. Provided one knows that the letters represent colours on a grid that is three by three. Without the context, the information may as well be noise.

But that is not given by "RRBGGGRWW".

Yep....even in the physical science the "differences that make a difference" are context dependent. — Count Timothy von Icarus -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?, phasers function using a rare element called plotonium. It allows them to eliminate whatever, and only whatever, the writer desires.

-

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?...we just can't know the physical basis — ENOAH

An odd thing to say. There is a physical basis for dividing the pipe in to blue and red, after all, and for dividing the tree into trunk and branches.

Certainly not. (insider joke)Is that as far as W went? — ENOAH

There's a poor mans version of "language game" that thinks all there are to language games are words. But from the get go language games involve things around us - slabs and blocks and apples and trees. -

An Analysis of "On Certainty"

Is it? A sentence is a string of words, and so at the least is not as abstract as something like "the thing that is common to 'it is raining' and 'il pleut'"...whatever that is.By the way, you haven't escaped abstract objects. A sentence is also abstract. — frank -

Criminal Commodity in the Early 21st Century: an Effect of the EnlightenmentI TL;DR'd it on ChatGPT and got

After the Enlightenment, a gradual movement toward equality began, aiming for political equality, economic mobility, and classless societies. This period, which started less than 300 years ago, continues to shape our world today. The Enlightenment inspired revolutions that established governments by and for the people, challenging the power of feudal lords and aristocrats.

One significant post-Enlightenment change was in city planning, where cities started to integrate different social classes. This period also saw the rise of cultural figures from lower classes, like Beethoven, who transcended social barriers through their art.

In the mid-20th century, American rock musicians, like those from The Doors, became modern equivalents of such cultural revolutionaries, defying traditional values and gaining widespread influence.

In the early 21st century, a similar pattern emerges in the financial world, where the appeal of a rebellious, criminal image is prized, reflecting the complex legacy of Enlightenment ideals and their impact on contemporary culture.

No apparent thesis. -

An Analysis of "On Certainty"Yep.

So, to make a start on Understanding On Certainty, Moyal-Sharrock, the contention there is something like that hinges are not belief-that, but belief-in, or trust.

Now I want to be clear that there is a use of the word "belief" that is belief-in, as opposed to belief-that. Indeed, it is clear from etymological considerations that this form is the earlier - back to the PIE root *leubh- for care, trust, love.

Moyal-Sharrock, I think rightly, rejects reducing belief-that to belief-in. Rightly, since these are at least superficialy different uses, with corresponding differences in their grammar. Belief-that takes a statement as its target, while belief-in takes some logical individual.

Moyal-Sharrock goes on to commit the reverse error, attempting to reduce belief-that to belief-in. Here we might do well to recall this:

We can interchange sentences between belief-in form and belief-that form; this does not show that either has some sort of priority.We might very well also write every statement in the form of a question followed by a "Yes"; for instance: "Is it raining? Yesl" Would this shew that every statement contained a question? — Philosophical Investigations §22

Moyal-Sharrock's discussion is broad and strongly argued, and this is but a start.

Banno

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum