-

Looking for the source of an old adageThanks so much! Should have guessed you would be the one to ask about this.

-

Looking for the source of an old adageIt sure sounds like one, but I'm not sure if I'm remembering it accurately, or if there's anymore specific source than just "Zen Buddhists".

-

Towards a Scientific Definition of Living vs inanimate matterI do like your general direction as well, however, your particular definition Suffers from including Crystal growth As a living being, because Crystal growth uses a flow of energy to do productive work upon itself (Build its more ordered lower entropy structure) So it does reduce its own internal entropy And transfers the entropy difference as he to the environment. — Sir Philo Sophia

I thought that crystals were excluded from my definition because a crystal is not in itself a machine. Crystals are lower-entropy than other arrangements of their constituent molecules, and they are produced when energy flows out of the system they are a part of (when temperature decreases). But they are just a product of that lower energy favoring a lower-entropy configuration, they are not exploiting the change in energy to do work (as they must to be considered machines), which work in turn reduces their entropy.

I think that is problematic as well because gravity does fight against the second law of thermodynamics as it reduces entropy when matter clumps up together ( less micro-states are available for the matter to explore). — Sir Philo Sophia

That is pretty much the same as my take on crystals above: the collapse of things under gravity can locally reduce entropy, and even power machines that can then reduce their own internal entropy, but that collapse itself is not life by my definition.

However, I am much more comfortable with an energy and work Framework of defining life than a nebulous/abstract and information entropy related one. — Sir Philo Sophia

I am also focusing on work as a primary factor of my definition; that's why I thought your definition was so similar to mine. The principle of least action is very closely related to entropy, such that veering away from the course least actions is basically the same thing as resisting the increase of entropy.

I've always enjoyed reading your posts on other topics so I look forward to your further thoughts and/or critique on the subject. — Sir Philo Sophia

Thank you very much, it's so nice to hear some positive feedback here, where it seems almost all of the responses are negative.

With that established, I then define "life" as "self-productive machinery": — Pfhorrest

Ah. But the question when it comes to life is how can a machine self-reproduce. — apokrisis

Please note that I didn't just mean machinery that produces other machinery like itself, but rather, machinery that does "productive" work, in the sense that I defined it in that post, upon itself.

I like that von Neumann quote, though. -

Towards a Scientific Definition of Living vs inanimate matterMy own definition of life is very similar to yours, so I think you're on the right track at least.

My definition hinges on the physics concept of a "machine", which is any physical system that transforms energy from one form to another, which is to say it does "work" in the language of physics.

I propose the definition of a property of such physical work, called "productivity", which is the property of reducing the entropy of the system upon which the work is done.

With that established, I then define "life" as "self-productive machinery": a physical system that uses a flow of energy to do productive work upon itself, which is to say, to reduce its own internal entropy (necessarily at the expense of increasing the overall entropy of the environment it is a part of).

The universal increase of entropy dictated by the second law of thermodynamics is the essence of death and decay, and life in short is anything that fights against that.

It is alive when it is in the middle of hijacking some host cell's metabolic machinery. That fits the definition. — apokrisis

That fits mine too. To my mind, the environment of a host cell is the condition in which a virus is able to live. Just as a human dumped in the vacuum of space would cease to live, so too would a virus dumped out of any host cell.

Certain man-made devices may also count as "alive" under my definition (provided they are in an appropriate environment, just like the virus: plugged into electricity, etc), and I'm fine with that. That doesn't give e.g. my computer, which uses the flow of electricity through it to process information in a way that reduces its own internal entropy, any special moral status just because it's "alive", any more than viruses or amoebae are important moral patients.

It's not just life, but sentience, that makes something a moral patient, on my account. Where "sentience" is the differentiation of experiences into "is" and "ought" models of the world, the differences between which then drive subsequent behavior, rather than behavior being a simple direct response to a simple direct stimulus. In such a way the system in question can have some (reflective) experience of things "not being how they ought to be", e.g. pain, when one model differs from the other. -

People Should Be Like Children? Posh!There’s an old adage that a philosophy professor related to me once (if anyone knows the source of this please let me know it). It went something like “Before one walks the path of enlightenment, tables are tables and tea is tea. As one walks the path of enlightenment, tables are no longer tables and tea is no longer tea. After one has walked the path of enlightenment, tables are again tables, and tea is again tea.”

Meaning that the general view of the world that one ends up with after mastering philosophy is one that is not radically different from the naive pre-philosophy view that people start out with, but that on the way from that naive beginning to the masterful end, one’s whole worldview gets turned upside down and inside out as one questions everything. The thing the master has that the beginner does not is an understanding of why those “obvious” answers are as they are and all the insanity they explored along the way was wrong.

I bring this up because I think all the dark philosophy you see here is from people still “on the road to enlightenment”, who have rightly begun to question everything, but who haven’t yet discovered why the “obvious” answers were right along.

A child knows the obvious answers... but doesn’t yet know why those are the right answers. -

Is panprotopsychism really a form of pan-psychism?So your argument is that panprotopsychism should not count as a kind of kind of panpsychism because panprotopsychism is actually a plausible view but you want to be able to say that panpsychism isn't and you can't do that if the plausible view is a subtype of the view you want to be implausible?

but it completely lines up with physicalism or materialism if you really think about it. — turkeyMan

Yep, and that's a good thing. -

Why people enjoy musicI meant the pattern recognition thing this time too. By "directly" I mean that music is composed of patterns that are not the naturally-occurring patterns that our brains evolved to detect and react to, but rather hyper-refined patterns in an abstract medium that trigger those same mental responses with much more power and precision than the natural phenomena.

That's why I used the analogy with adding sweeteners to food. Adding a ton of sugar to something can make the experience of it much more enjoyable than any food that you could possibly find in nature. Likewise, producing a bunch of the right kinds of patterns in sounds can make an experience much more intense than the kinds we would often find in nature. -

People Should Be Like Children? Posh!Adults are selfish too. And if anything I was happier being alone as a child than I have been as an adult. I could entertain myself for untold ages as a child, but when life sufficiently traumatized me to the point that I was having an existential crisis for basically the entirety of last year (ironically enough, an objectively fine year, while during this apocalyptic year I've been feeling relatively fine in comparison), I found myself to crave human comfort.

I do think it may seem like people improve with age for a lot of people who get traumatized earlier in their lives than I did, and then spent a lot of their adulthood healing from that, or at least adapting to it. Basically their mental health went downhill so early on in their lives that on a long scale it looks like it's been improving as they age, but really it's just shambling haphazardly toward the health of newborn innocence again. -

Can the viewpoints of science and the arts be reconciled ?Now that I have a moment to elaborate further:

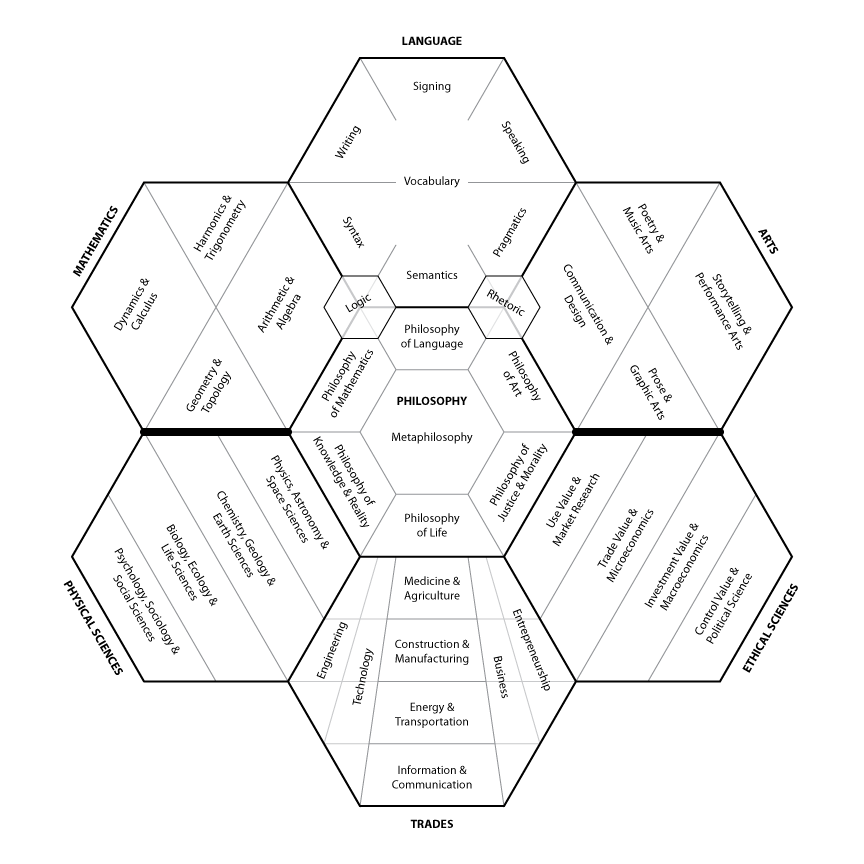

I see the primary axis as from abstract language to practical trades, and philosophy bridges those two things.

Off in the wings of that axis are two other axes: one of them is basically two forks off of language (one of which is the arts), and the other are the two inputs into the trades (one of which is the physical sciences). Philosophy sits also in the middle of each of those axes.

One fork off of language concerns the style, presentation, and delivery of the content of communicative acts in both verbal and non-verbal forms. That is the arts.

The other fork off language concerns the form and structure of communication. That is mathematics.

Philosophy uses tools from the core of each of those -- rhetoric from the arts, and logic from mathematics -- to do its job, which is creating and defending the foundations for those two inputs into the trades.

One of those two inputs is the investigation of reality: the physical sciences. The physical sciences can also be construed instrumentally as discovering the "natural tools" that are available to use, from which engineers can then create more purpose-built tools, for technologists to administrate the use of to do various jobs in the trades.

The other of the two inputs to the trades, which is sadly underdeveloped in our world today, is what I would call the "ethical sciences", which can be construed as the investigation of morality, or equivalently as discovering the "natural jobs" that need doing. That research could then, I think, well inform entrepreneurs, as a form of market research, to create more purpose-built jobs, for business people to administrate the doing of in the various trades.

Mathematics and the arts, though very distinct in the way elaborated upon above, also dovetail into each other in many ways. For every branch of the arts, there is some branch of mathematics that is applicable to its realization.

Geometry and other spatial branches of mathematics have obvious applicability to the visual arts.

The mathematics of cyclical functions, patterns that repeat over time, underlies harmonics, which has obvious applicability to the musical arts. In medieval education curricula, that study of mathematical harmonics was even taught under the label of simply "music", one of the four subjects of the quadrivium.

Alongside that in the quadrivium were arithmetic, the aforementioned geometry, and what they called "astronomy", which was really the study of the mathematics of dynamics, which does have its applications in literal astronomy of course, but also has obvious applications in performance arts like animation where it is necessary to realistically depict motion in space over time.

Likewise, as the most general and fundamental subfield of the ethical sciences plays the foundational role to them that physics plays to the physical sciences. That field's task would be to catalogue the needs or ends, and the abilities or means, of different moral agents and patients, like how physics catalogues the functions of different particles.

Building atop that field, the ethical analogue of chemistry would be to catalogue the aggregate effects of many such agents interacting, as much of the field of economics already does, in the same way that chemical processes are the aggregate interactions between many physical particles.

Atop that, the ethical analogue of biology would be to catalogue the types of organizations of such agents that arise, and the development and interaction of such organizations individually and en masse, like biology catalogues organisms.

Lastly, atop that, the ethical analogue of psychology would be to catalogue the educational and governmental apparatuses of such organizations, which are like the self-awareness and self-control, the mind and will so to speak, of such organizations. -

Why people enjoy musicI think my theory can and does explain how music can invoke such strong emotional states, since it's directly pushing emotional buttons normally triggered by pattern-recognition that evolved for more real-world purposes. It's like adding sweeteners to food, our brains just go "YES YES YES THIS IS THE MOST NUTRITIOUS THING EVER" because we're wired to gorge ourselves on calorie-rich foods whenever we can... even though sweet food isn't necessarily the most nutritious thing ever.

But I do definitely see the connection with religion as well, and I think religions have applied "musical" concepts (figuratively as well as literally musical ones) to other aspects of life exactly like I was discussing in my last paragraph. For example, ritual creates a sense of comfort, because it's a predictable pattern, so religious rituals make people feel comforted. (See also how people under severe emotional distress will tend to rock themselves, because the repetition there also creates a sense of comfort).

It seems highly unlikely song as we know it came first. We would expect to observe this behavior in at least one nonlinguistic animal. — hypericin

I'm not sure exactly how this connects, but apparently the human brain has a different function for singing than for speaking, because there are people with neurological disorders that leave them unable to speak, but they can still sing. -

Liberty to free societies! We must liberate the people from the oppression of democracy and freedom!Freedom is rather central to our moral systems though, so I'd argue more than just commerce is at stake. — Echarmion

I agree and didn't mean anything contrary to that. Rather, that moral principles (including those regarding freedom) apply to commerce as much as they do to anything else.

Is it? Doing nothing is already a value judgement. You're only really doing nothing when you're not conscious. So refering to doing other things as nothing is already judging them as irrelevant to the question. But can your everyday conduct, which falls under the "nothing" here, really be ignored when talking about freedom? — Echarmion

By "doing nothing" I mean making no noticeable difference from if you hadn't existed at all. Failing to help someone who would be in the same situation if you had never existed to begin with is doing nothing, and doing nothing wrong. (It is still omitting a good, but an omissible one, not an obligatory one; it's not prohibited, it's just suboptimal). If the person is only in that situation because of something you did, or are doing, that's a different story; that's not doing nothing.

(I like to think of this in terms of an example given for part of Asimov's Three Laws of Robotics: the part about "...or through inaction allow a human to come to harm", that being supposedly necessary because without it a robot could set some events into motion that would not harm any human provided the robot followed up with some other action, but then simply not perform that followup, and merely "allow through inaction" a human to come to harm, but not "harm a human". I think that's an unnecessary complication of the laws, because if the robot performs the initial action without the followup then it is directly harming a human, not just allowing a human to come to harm. The robot is already required to act however necessary to prevent any of its actions from harming humans, because if it didn't, it would have harmed a human. An additional requirement prohibiting inaction is unnecessary).

But even if Jeff Bezos and the beggar were trending towards the middle, that'd still not address the imbalance in their relation to each other. — Echarmion

The point is that were it not for the runaway concentration of wealth and poverty, Bezos and the beggar would not have that imbalance to begin with. If we're starting with a situation where that imbalance already exists, then we need to take some positive actions to correct that injustice, sure. But in a properly structured society it should not be possible for such imbalances to come to be in the first place, so no such measures should be needed.

(We are, obviously, not in such a properly structured society, because those imbalances do exist, and so corrective measures are needed, in our society).

This seems a fairly thin justification. After all, you know in advance just what interest you own, and hence you're not under some arbitrary authority of the lender. — Echarmion

You don't know in advance exactly what interest you will owe. That depends on when you make your payments and how much those payments are. In agreeing to interest, you haven't just agreed that you owe someone a certain amount of money in exchange for some good or service, but you've agreed to owe them more money later, whether at that later time you want to agree to owe them more or not, and not in exchange for any further good or service, but just automatically: for every unit of money, for every unit of time, you owe them some further unit of money, on top of the amount you already agreed you owe them.

Under my principles, you couldn't have such a contract: a contract consists only of waiving a claim (transferring ownership of a good) or waiving a liberty (taking on an obligation to do or not do something) in exchange for the other party doing likewise. You do not have the power to waive your immunities, in other words to transfer away your exclusive power to change your first-order rights (by contract); and you do not have the power to waive your powers, in other words to take on obligations to permit or not permit things. Contracts of rent or interest purport to be "selling" someone the temporary use of your property, but letting someone do something is not itself doing something.

Also, adjustable-rate mortgages are a thing in the real world, and that's an extremely clear case of not knowing what your interest is going to be.

To summarize my original point. and I think our important point of agreement here (bolded in the below):

At first glance, one would think a maximally libertarian society would be one in which there were no claims at all (because every claim is a limit on someone else's liberty), and no powers at all (because powers at that point could only serve to increase claims, and so to limit liberties).

But that would leave nobody with any claims against others using violence to establish authority in practice even if not in the abstract rules of justice, and no claims to hold anybody to their promises either making reliable cooperation nigh impossible.

So it is necessary that liberties be limited at least by claims against such violence, and that people not be immune from the power to establish mutually agreed-upon obligations between each other in contracts.

But those claims and powers could themselves be abused, with those who violate the claim against such violence using that claim to protect themselves from those who would stop them, and those who would like for contracts not to require mutual agreement to leverage practical power over others to establish broader deontic power over them.

So too those claims to property and powers to contract, which limit the unrestricted liberty and immunity that one would at first think would prevail in a maximally libertarian society, must themselves be limited as described above in order to better preserve that liberty. -

People Should Be Like Children? Posh!The adult mindset is basically the child's mindset plus many years of scars and trauma.

I was fortunate enough to be spared from a lot of that scarring and trauma until adulthood, so I have clear memories of being an adult with a healthy childlike mind, and of my gradual decay into the way that everyone else always seemed to be. -

Liberty to free societies! We must liberate the people from the oppression of democracy and freedom!the way it frames social relations in commercial terms — Echarmion

I see it rather as framing the foundations of commerce in social terms.

That is as a system where the only positive relationship between people is a contract, and outside of this you only have purely negative relations to other members in the society, i.e. the only obligations are those to refrain from a specific set of actions. — Echarmion

Such that if you are doing nothing, you are doing nothing wrong, which is as it should be.

It ignores the way humans are dependent on mutual aid from one another, and can thus treat a homeless beggar as free as Jeff Bezos. — Echarmion

The problem stems from there being such a difference between the beggar and Bezos in the first place, which my modification to the usual contractual-propertarian libertarianism is meant to address. If a society's deontic principles result in the already-rich getting richer and the already-poor getting poorer, rather than everyone trending toward the middle over time all else being equal, then something somewhere has been done wrong, and I identify that "something done wrong" as primarily the institutes of rent and interest.

But do not all ongoing relationship limit your power to contract? Or even large individual purchases? Taking up a mortgage to buy a house is a very significant limitation to my further ability to contract. — Echarmion

In practice perhaps, but not in the structure of the contract itself. A mortgage contract doesn't say that you may not enter into other kinds of contracts. It does, however, say that upon certain conditions you pre-emptively agree to owe more money than you've already agreed to owe (interest), which would be invalid under my principles.

And this also puts wage labor in a problematic position, because part of a contract as a laborer is that you place yourself under the authority of another person in a limited and specific way. While the obligation is generally not enforceable in industrialised countries, it's still there. — Echarmion

That is a plausible interpretation of my principles and I don't object to its implications. -

Liberty to free societies! We must liberate the people from the oppression of democracy and freedom!It is not just freedom-to that matters but freedom-from. This is the difference between liberty rights and claim rights: the former is having to obligations, the latter is someone else having obligations to you, such as not to assault you.

Also relevant are the second-order versions of both if those: the power to make changes to those first-order liberties and claims, and the immunity from such powers.

The usual conception of a maximally free society allows maximal liberty, except as limited by claims to property, including one’s own body (“that’s me/mine, you can’t do that unless I consent”) as well as maximal immunity except as limited by the power to contract (nobody can change your liberties or claims unless you agree to it).

I like to note that we generally make an exception on those minimal claims, and say that it is okay to act upon someone or their property without their consent as necessary to stop them from acting upon others likewise.

And I also advocate a similar exception to the power to contract, saying that people are immune from contracts that would limit their ability to exercise their power to contract. This not only means that you can’t sell yourself into slavery, but also things like non-compete clauses, and broadly all contract of rent and interest, fall afoul of this exception.

I think that that last bit is the big thing really missing from the notion of freedom advocated by modern American-style libertarians, and that adding it is the solution to reconciling their propertarian libertarianism with libertarian socialism. -

What does morality mean in the context of atheism?:up:

Since you liked that short quip so much, I thought you might enjoy some more fleshed out versions too:

----

When it comes to tackling questions about reality, pursuing knowledge, we should not take some census or survey of people's beliefs or perceptions, and either try to figure out how all those could all be held at once without conflict, or else (because that likely will not be possible) just declare that whatever the majority, or some privileged authority, believes or perceives is true.

Instead, we should appeal to everyone's direct sensations or observations, free from any interpretation into perceptions or beliefs yet, and compare and contrast the empirical experiences of different people in different circumstances to come to a common ground on what experiences there are that need satisfying in order for a belief to be true.

Then we should devise models, or theories, that purport to satisfy all those experiences, and test them against further experiences, rejecting those that fail to satisfy any of them, and selecting the simplest, most efficient of those that remain as what we tentatively hold to be true.

This entire process should be carried out in an organized, collaborative, but intrinsically non-authoritarian academic structure.

----

When it comes to tackling questions about morality, pursuing justice, we should not take some census or survey of people's intentions or desires, and either try to figure out how all those could all be held at once without conflict, or else (because that likely will not be possible) just declare that whatever the majority, or some privileged authority, intends or desires is good.

Instead, we should appeal to everyone's direct appetites, free from any interpretation into desires or intentions yet, and compare and contrast the hedonic experiences of different people in different circumstances to come to a common ground on what experiences there are that need satisfying in order for an intention to be good.

Then we should devise models, or strategies, that purport to satisfy all those experiences, and test them against further experiences, rejecting those that fail to satisfy any of them, and selecting the simplest, most efficient of those that remain as what we tentatively hold to be good.

This entire process should be carried out in an organized, collaborative, but intrinsically non-authoritarian political structure.

----

With regards to opinions about reality, my philosophy boils down to forming initial opinions on the basis that something, loosely speaking, looks true (and not false), and then rejecting that and finding some other opinion to replace it with if someone should come across some circumstance wherein it looks false in some way.

And, if two contrary things both look true or false in different ways or to different people or under different circumstances, my philosophy requires taking into account all the different ways that things look to different people in different circumstances, and coming up with something new that looks true (and not false) to everyone in every way in every circumstance, at least those that we've considered so far.

In the limit, if we could consider absolutely every way that absolutely everything looked to absolutely everyone in absolutely every circumstance, whatever still looked true across all of that would be the universal truth.

In short, the universal truth is the limit of what still seems true upon further and further investigation. We can't ever reach that limit, but that is the direction in which to improve our opinions about reality, towards more and more correct ones. Figuring out what can still be said to look true when more and more of that is accounted for may be increasingly difficult, but that is the task at hand if we care at all about the truth.

(It is trivially simple to satisfy everyone's different sensations with a theory that we’re all in different virtual worlds being fed different experiences, but theories that involve us all being in the same world together get trickier).

----

With regards to opinions about morality, my philosophy boils down to forming initial opinions on the basis that something, loosely speaking, feels good (and not bad), and then rejecting that and finding some other opinion to replace it with if someone should come across some circumstance wherein it feels bad in some way.

And, if two contrary things both feel good or bad in different ways or to different people or under different circumstances, my philosophy requires taking into account all the different ways that things feel to different people in different circumstances, and coming up with something new that feels good (and not bad) to everyone in every way in every circumstance, at least those that we've considered so far.

In the limit, if we could consider absolutely every way that absolutely everything felt to absolutely everyone in absolutely every circumstance, whatever still felt good across all of that would be the universal good.

In short, the universal good is the limit of what still seems good upon further and further investigation. We can't ever reach that limit, but that is the direction in which to improve our opinions about morality, toward more and more correct ones. Figuring out what what can still be said to feel good when more and more of that is accounted for may be increasingly difficult, but that is the task at hand if we care at all about the good.

(It is trivially simple to satisfy everyone's different appetites with a strategy to put us all in different virtual worlds and feed us different experiences, but strategies that involve us all being in the same world together get trickier). -

What does morality mean in the context of atheism?It's a bit like asking God for absolute verification of our observations. — Echarmion

It’s absolutely like that. We don’t need to appeal to God to compare our experiences and come to an unbiased consensus on what is real, nor do we need to appeal to him to compare our experiences and come to an unbiased consensus on what is moral.

When i wrote the question i was hoping to find out if A) it was general accepted amongst atheists that morality wasn’t an objective reality and B) weather or people believe in morality as an objective reality despite being an atheist. — Restitutor

No and yes, more or less. (Morality isn’t “a reality” in any sense, but it is every bit as objective as reality). -

Critical liberal epistemologyThere is no argument for it other than constant experience of it, and total lack of counterexamples to it. — Janus

...which is only an argument at all if you think induction works already, which is why that makes the argument circular.

You keep falling into the trap of thinking there must be a purely logical argument — Janus

I think a pragmatic argument works fine, and since you also seem to give pragmatic arguments, I don't see why you think there also has to be anything more. Hume is the one who doesn't seem to consider pragmatic arguments as a possible avenue, and who thus sees a problem.

We're just going in circles now — Janus

Just like Hume said you would! ;)

time to quit I think — Janus

I've been trying to quit this thread for weeks(?)now.(?) [time has no meaning anymore] -

Critical liberal epistemologyAs I said earlier I think he is just pointing out that there is no deductive certainty, no logical necessity, that nature's observed regularities will remain in place in the future. — Janus

He explicitly considers the possibility of inductive arguments in favor of that, though, and then rejects them as being circular, which suggests that he would have been satisfied that there was reason to believe it if an inductive argument to that effect could work, no deduction required -- but because an inductive argument would have to rely on exactly that thing he's looking to argue for, it can't work, because of circularity. -

Critical liberal epistemologyBut it is obvious that induction has worked; — Janus

To those who find it is obvious, sure. To those who don't, what then?

there is no more need of argument for that than there is to justify saying the sun has always risen on earthly life — Janus

There is if you want to change the mind of someone who doesn't already believe that.

NB that I'm not saying "you need to show me an argument if you want to believe this". That's half the point of my view in the OP: nobody needs to show an argument to anyone else just to be allowed to believe something. But if you want to tell someone else that they're wrong (e.g. if someone doesn't believe in induction, and you want to tell them they're wrong not to), then you absolutely do need an argument.

Can you give an account of any other means of arriving at confirmable/ dis-confirmable beliefs than induction? — Janus

Someone tells you something, and you don't know any better to the contrary, so you believe them.

Or:

It'd be really nice if something were the case, and you're not certain that it's not, so you tell yourself that it is.

Just for two examples.

Can you give an example of two competing beliefs, and explain how induction would not be at all involved in deciding between them. — Janus

Some phenomenon has occurred in the past in this pattern: twice one day, four times the next day, eight times the next day.

One person believes on the basis of induction that that phenomenon always occurs in pairs, and always increases, though in no particular pattern.

Another person believes that it always increases exponentially, but not necessarily in pairs or even power-of-two exponents, this one just happens to be doubling.

They look to see how the pattern continues: the next day, the phenomenon occurs 16 times.

That fits both of their induced hypotheses, and so doesn't tell us which of them is more or less correct.

Yes, of course we shouldn't demand absolute proof of anything before believing it; that is very the nature of induction — Janus

Yes, which is why induction is a fine reason to believe something on my account.

NB though that on my account, if someone else believes something, and you don't see a reason to, but they do, in the same data, you can't demand that they convince you of the pattern that they see to justify their belief via induction, or else that they discard it. They don't need to show you a reason to believe it in order to be allowed to believe it. You need to show them a reason not to believe it, if you want them to change their mind.

Other kinds of belief; aesthetical, ethical or metaphysical are discarded, if they are, for personal reasons; there can be no inter-subjectively definitive reasons in those cases. By that I mean there can be no reasons that a suitably educated unbiased observer would be bound to accept. — Janus

I disagree, but that's beyond the scope of this thread.

As I understand it, the problem is not only that it can't deliver certainty, but that there's no good reason to think it would deliver any support at all, even merely probabilistic support. — Pfhorrest

That's where we definitely do disagree. I think... — Janus

You misunderstand me, I wasn't saying what I think there, but what my understanding of what Hume says is. As I understand Hume, he is pointing out that there can't be given any convincing reason to think (i.e. any way to change the mind of someone who doesn't already think) that induction lends any support to anything, because its negation is not a straightforward contradiction (which would be needed for an a priori deductive argument), and the only other kind of argument (so he thinks) is itself an inductive one, which of course won't convince someone who's not already convinced of induction. -

Why is panpsychism popular?:up: :100:

"Magic" isn't just the unexplained, it's the fundamentally unexplainable. To deny something because it would be magic is to deny that anything is fundamentally unexplainable.

Strong emergence suggests the appearance of something from nothing and for no reason: when you arrange some stuff together, some new stuff appears, not because of anything to do with the pre-existing stuff, but just because.

(If the new stuff did have anything to do with the underlying stuff, that would be merely weak emergence, and not magic, not unexplainable, just surprising and unexplained, but still in principle reducible to the fundamental underlying stuff). -

Critical liberal epistemologyInduction obviously does work; to give us all our beliefs and understandings of the world. So, there is no need to provide an argument for that. — Janus

"It's obvious" is not an argument, and you do need an argument if you want to convince anyone who doesn't agree with you to change their minds.

Are you denying that induction has worked, or what? — Janus

No, I've been saying all along that induction is just fine, it simply has nothing to do with the point of this thread. I was never arguing against induction as a means of coming to our beliefs, only that by itself it doesn't give us a way of choosing between competing beliefs, and that it's not necessarily the only way of coming to believe things either. (And for my purposes it doesn't matter whether it is or isn't the only way, because my methodology is okay with any ways of coming to believe things, so long as you leave them open to falsification).

Every time someone critiques what they think you are claiming, you say 'no, it's not that', and yet you seem to be incapable of explaining what else it is you are trying to convey. — Janus

I think it's because I'm really saying very little at all here, and everyone seems to think I'm saying much more than I am.

I'm saying first of all that within some very broad limits, anything is okay. Those limits are:

- don't demand absolute proof of anything before allowing yourself (or others) to believe it, go ahead and believe things for whatever reason you're inclined to (induction or whatever else);

- so long as everything you believe, you believe tentatively, fallibly, non-dogmatically, in a way such that you would discard that belief if you came across reason to do so.

(I expected that on a philosophy forum, philosophy being traditionally a reason-centric enterprise, everyone would take the latter as a given, except maybe some religious folks; and the former would be the point of contention, from self-identified "rational skeptics" who don't realize that that methodology applied consistently would leave nobody able to ever learn anything at all).

And then I'm saying as a consequence of that broad approach, hypothetico-deductive confirmationism has no legs to stand on, because:

- just seeing an expected consequence of your belief can't give you any more justification than you already had to continue believing it (because you were already perfectly well-justified in believing it, for whatever reasons you already did);

- and it doesn't necessarily rule out any of the alternatives (and in the cases where it does, that's falsification right there, so the only the cases where such confirmationism works are the cases where it's indistinguishable from falsificationism).

the problem of induction as I understand it, according to Hume, is that it cannot deliver deductive certainties. — Janus

As I understand it, the problem is not only that it can't deliver certainty, but that there's no good reason to think it would deliver any support at all, even merely probabilistic support.

We all naturally act like it does, Hume included, but Hume noted that if we really question whether we should or shouldn't act like that, there's no way of presenting an argument that we should, because that argument would either have to rely on us already thinking that we should (in relying on an inductive argument to argue for relying on inductive arguments), or else require that its negation be self-contradictory (which it's just not). That doesn't (even supposedly) prove that induction doesn't work, only (supposedly) that there can be no good explanation as to why we should expect it to work.

You, like I, have been arguing that we pragmatically have to expect it to work (or rather, in my case, why we should expect the universe to behave in a lawlike way, which is a prerequisite for induction working), or else we can't get any kind of science done. Elsewhere I've fleshed out a more rigorous version of that kind of argument, and I think that that's a fine reason to expect the universe to behave in a lawlike way. I don't know why you think a circular argument for induction that relies on induction is even necessary, given such practical lines of argument, never mind how you don't see why they don't work. -

Critical liberal epistemologyWithout that network of beliefs there would be nothing to operate upon. — Janus

Sure, I never disputed that.

Sure, it's circular, but that doesn't matter for inductive purposes, The problem with circular deduction is that it tells you nothing. Induction however, tells you everything you know (or believe, if you prefer) about the world. — Janus

IF induction works, which you would have us believe on the grounds that “it aways has worked”, which would only be reason to believe induction worked if you already believed indiction worked.

I am not rejecting induction here, I have my own solution to the problem of induction I’ve already given, I’m just pointing out that your solution doesn’t work as an argument. If you were to argue to someone who doesn’t believe in induction that it always has worked so we should expect it to keep working, they would only be persuaded by that if they ALREADY believed in induction, which they don’t. That’s the heart of the circularity: it’s not convincing to someone who doesn’t already agree.

You said earlier that Hume has refuted induction — Janus

No I didn’t, I said that he presented the Problem of Induction, which needs to be addressed. I think it can be, and I think I know how. It seems like Hume must have figured there must be some way, because he like everyone acts like induction works, but didn’t know how exactly to give reason to think it would.

We accept experience and observation because we must; there simply is no other way to gain the material from which we can extrapolate our hypotheses about the way the world is and works. — Janus

This is a pragmatic argument much like my own, not a circularly inductive one.

It makes no sense to say that anything can be pragmatically proven — Janus

That’s why I put “proven” in scare quotes. Hume talks about “demonstrative” (deductive) and “probable” (inductive) arguments, and shows how neither kind can give reason to believe in induction (e.g. to convince someone who doesn’t already believe in it). I instead give, and above you seem to give, a pragmatic argument, a reason why we must act on the assumption, even though it’s not possible to prove it either way, because to do otherwise would simply be to give up.

But none of that has anything to do with anything I’m talking about in the OP. -

Critical liberal epistemologyYes, but it does use an extensive interrelated network of inductively derived beliefs without which it would be operating in a vacuum, and be unable to confirm or dis-confirm any hypothesis. So, given that, it doesn't make sense to minimize the role of induction, and claim that is is really just falsification doing all the work. — Janus

It operates ON that network of beliefs, or any other network of beliefs formed in any other way; it doesn’t at all depend on the network of beliefs being formed by induction.

I was just thinking earlier today that even as much as I dislike Feyerabend overall, my principle of “liberalism” is actually most of the way to his “epistemic anarchism”, in that it says that any method for coming up with beliefs is fine, there is no prescribed method that you have to follow in order to be initially permitted to hold a belief. But on my account there is still the requirement that you be open to revising any beliefs, however you formed them, and not hold any of them beyond all question.

I’m not super well versed on Feyerabend, so I might be wrong about this, but I suspect he would agree with that last caveat as obvious and not at all against his point, which makes me now wonder if his whole point wasn’t just basically the same as my “liberalism”, and maybe I should give him another more charitable reading.

This response shows again that you are trying to apply the criteria for valid deduction to inductive reasoning. It puzzles me that you apparently can't see that. — Janus

I’m not using deduction there at all. Induction has seemed to work many times in the past, so inductively that should give us some (but not deductively certain) reason to think that induction will always work. If that not your argument? Does not that argument rely on already accepting that inductive reasoning gives some reason to believe something, in order to show that inductive reasoning gives some reason to believe something? Is that not circular, even though no deduction is involved?

This again shows that you are not acknowledging the role of induction. The general regularities of nature that we all observe, and never consistently observe any counterexamples to, and are thus induced (induction) to believe in must persist, because otherwise there would be no science, no human life, no life at all, and thus certainly no falsification. — Janus

I agree that we have to assume the universe obeys regular laws in order to get anything done, but I think that that practical reason is enough to justify assuming that, even if we hadn’t yet noticed any particular lawlike patterns yet. That assumption is in turn necessary to do induction — which is the whole Humean problem of induction, because he shows that it can’t be inductively proven without circularity and it can’t be deductively proven. I think the solution to that problem is that it can be pragmatically “proven”. You on the other hand just run around one circle of Hume’s fork. -

Why is panpsychism popular?↪khaled

So it’s just word play that brings comfort by the appearance of internal coherency, it doesn’t explain anything or help us grapple with the real world, in line with my first comment. Personally I don’t want to waste my time with that. — Saphsin

His point is that its negation is exactly like that as well, so you can't help but waste your time on either one or the other. -

Critical liberal epistemologyis exactly that, a prediction about the future - that there would be no observations of black swans in it. — Isaac

So you think that nobody holds any categorical beliefs like that, even defeasibly, such that they could find out that such beliefs were wrong when they observed something that was unexpected according to such a belief? Nobody can ever be wrong, because nobody ever has any expectations of how the future will turn out?

Again, you're ignoring the effect of states of uncertainty. I know you keep saying that you've included uncertainty by attaching the word 'probably' to your original theses, but tacking on the word 'probably' doesn't even begin to address the complexities of adding probability and uncertainty (or it's opposite) to the understanding of beliefs. — Isaac

I never said that just tacking on the word “probably” solved everything, that’s just the natural way of casually conveying in normal language the gist of the actual statistical math that needs to be done on the ground. What else besides “If A is true then B is probably true” would be a natural-language way of conveying the meaning of something like “P(B|A) is close to 1”?

You treat them as if we can innumerate and resolve them one at a time (again, despite your protestations to the contrary, you keep coming back to simple examples as if they encapsulated a principle which applied more widely). In the situation regarding the observation of a black swan - if you isolate the observer from all social connections, all linguistics, all embodiment and all cognitive context - it may just be the case that he would simply choose between the two options you describe. But there are no such people, and in reality the situation is vastly more complex to a point where this simple algorithm is next to useless. — Isaac

You’re ignoring that one of those two options is the extremely broad “or something else that I’m assuming, which leads me to believe this is a black swan I’m seeing, is false”. There are lots of (perhaps infinitely many) possibilities embedded in there. All the complexity you say I’m ignoring is in there.

The point is simply that if all your beliefs tell you that you’re seeing something that’s impossible (or improbable), then that combination of beliefs is impossible (or improbable), so you should (probably) change those beliefs, somehow. I’m not saying here how exactly you should, just that you should. -

Why is panpsychism popular?Doesnt anyone want to agree with Deacon that it's quantum theory? — frank

My panpsychism isn’t at all motivated by quantum theory, but it does touch on it. Basically, I think that “everything has consciousness” only in the same sense that in quantum theory “everything is an observer”: quantum theory doesn’t mean a thinking human-like observer, just anything capable of interacting with the system being “observed”, and like I don’t think the kind of “consciousness” that can be attributed to everything is the thoughtful human-like function that differentiates us from rocks, but a much more boring thing. I do think that both of those boring but superficially mystical-sounding things, quantum “observation” and phenomenal “consciousness”, can be identified with each other, because on my account (like Whitehead’s) “experience” in this sense is just one perspective on interaction. -

Why is panpsychism popular?In other words, the assumption that there are these physical objects that have no mental properties that somehow come together and suddenly have mental properties has gotten us nowhere, so people are starting to reject it. — khaled

I love the way you've phrased this. The things that we are most familiar with, ourselves, are conscious. We're generous enough to at least extend that to other things that look like us "from the outside" (third person); we suppose they're also like us "on the inside" (first person). Some of us are also willing to extend that to things that are similar enough to us, like other animals. But really, the big assumption being made is not by those who just say "sure, and the less like us on the outside, the less like us on the inside, but there's still some 'on the inside' all the way down", but those who say "...and then at some point there stops being any 'from the inside'", or worse yet, those who say "there's no such thing as 'from the inside', even for you or me".

We're most familiar with our own view from the inside, and the natural assumption (on the Principle of Mediocrity) would be that everything is also like that, that we're not special. If anyone had a burden of proof (and to be clear, technically I don't think anyone does, because epistemology), it would be those who want to say that we're special and most other stuff is fundamentally different from us. -

Why is panpsychism popular?So nothing is fundamentally strongly emergent, — Pfhorrest

Ok. So? — frank

That was my point that I thought you were disagreeing with. If I misunderstood you, then no further comment. -

Why is panpsychism popular?So recall that the distinction between strong and weak emergence is in assessments of truths. Read the essay. — frank

Okay, didn't see anything contrary in there. That's all basically what I thought about strong and weak emergence already.

The point stands that if there is anything not deducible from current theories of physics, then that means that we need to modify our theories of physics to be such that those things are now deducible from them, and in the end, nothing will be non-deducible from physics. So nothing is fundamentally strongly emergent, unless you take "the physical" to be only exactly what current theories of physics say it is; I'm not the one taking physics to be finalized already, I'm the one expecting it to be modified as necessary until it accurately accounts for everything.

In any case, Chalmer's position seems to be not dissimilar to mine, which is merely that having a first-person experience is not something that can be built up out of third-person facts; the third-person isn't "below" the first-person. But it doesn't then follow that if you put together the right third-person facts in the right way, then suddenly a wholly new kind of thing that was not at all present in the stuff you built that out of appears on top of the thing you've built.

If anything it suggests the exact opposite: that if a brain has a first-person experience, and modifying the brain modifies that first-person experience, then disassembling the brain into its constituent parts should disassemble the experience into its constituent parts, such that even the most elementary stuff in the universe has a kind of primordial "consciousness", in this sense that we should by now realize is not the sense ordinarily meant by the word, if even lone protons have it. In other words, panpsychism, at least about phenomenal consciousness, which is not consciousness as we ordinarily mean it.

And then both the behavior of our brains as physical systems observable in the third person, and the first-person experience those brains have when doing that behavior -- which together are the thing we ordinarily mean by "consciousness" -- can weakly emerge in unison (because they're actually two faces of the exact same function) as we rebuild those brains out of atoms again. But nowhere in that process of building brains out of atoms did a metaphysically new thing start happening that was not in principle deducible from the atoms themselves, i.e. strongly emerge. -

Why is panpsychism popular?If some updated physics could handle new, apparently strongly emergent properties, it would have to be by adding something to the fundamental constituents of physical stuff. Simulating those fundamental constituents, with the new physics, would then simulate the “strongly emergent” properties... this showing them to not have been strongly emergent at all. You’re basically saying that strong emergence is only relative to a particular incomplete account of physics, and on a complete, final account of physics, there would be nothing strongly emergent. Which is to say that in actual fact, nothing is really strongly emergent, at most it is mere unaccounted for by our present physics.

-

Critical liberal epistemologyI have addressed everything put forth. Me being of note or not is of no relevance. And just because other have come after and disagreed with Popper doesn’t make him conclusively refuted.

I have no problem with actual criticism of my position, if you've actually got something new to add that I haven't already accounted for. And I have absolutely no problem with people being unpersuaded by my arguments; I generally don't expect anyone to ever be persuaded by anyone.

The only thing I’m getting tired of is people attacking positions I don’t hold as though they were disagreeing with me, often by using points I already agree with myself. And when I point out that that’s not my position they’re attacking, and that I already agree with the points they have against that strawman, I’m accused of “digging in my heels”, “reiterating the same claims with no further argument”, “not addressing counter arguments”, etc. I generally feel like I'm faced with people seemingly offended that I’m not persuaded by their arguments to abandon the position that I never held in the first place, in favor of their position that I already agreed with.

TL;DR: I'm not bothered that anyone disagrees with me. I'm bothered that people seem bothered that I (they think) I disagree with them. Like the only thing that would make them happy is if I just said "ok you're right" and shut up, no responses allowed. -

Why is panpsychism popular?A weakly emergent property is not reducible. — frank

A weakly emergent property will also emerge from a simulation of the underlying system. Simulate particles in of a gas just mechanically and you simulate temperature automatically.

Strongly emergent properties aren’t like that, and that’s what makes them like magic. You don’t just get them from some combination of the underlying behaviors, but they’re something else in addition to those parts and their arrangements. -

Critical liberal epistemologyIt can be amusing to watch someone defending their theory against obvious falsification. — Banno

I wish I could say it was amusing to watch someone selectively read and willfully misinterpret so as to score cheap internet points instead of having an honest conversation, but reality it’s just petty and irritating.

For instance:

Again, it would have been irrational, unreasonable, improper, even crazy, for her to doubt that the kettle would boil.

Yet you would make such doubt the cornerstone of epistemology. — Banno

If you actually read anything in this thread at all, you would see that fully half of my point is against the same greedy skepticism you’re arguing against here.

I didn’t ask if she doubted it, and I didn’t say she should. I asked if she would have been open to revising her belief had there counterfactually turned out to be evidence against it. Because that’s all that “tentative” means, and “dogmatic” is the opposite of that.

You are conflating dogmatism with what I call “liberalism”, and also conflating “critical” skepticism with “cynical”skepticism, exactly as I said opponents to the OP would mistakenly do. -

Why is panpsychism popular?For instance, consciousness? — frank

If by consciousness you mean some kind of metaphysical quality that human brains have that is totally irreducible to any aggregate of qualities that the stuff brains are made of have, then yes. That’s strong emergence, of phenomenal consciousness, and it would be some weird spooky magic if it actually happened like that.

But if you instead mean a thing that brains do that is perfectly reducible to an aggregate of things that the stuff brain are made out of do, then no. That’s only weak emergence, of access consciousness, and it’s a normal and completely uncontroversial thing. -

Why is panpsychism popular?Obligatory note to differentiate between strong and weak emergence, here.

Weak emergence is uncontroversial.

Strong emergence is tantamount to magic. -

Critical liberal epistemologyPolly's belief was not at all tentative. — Banno

So she is not at all open to the possibility that it could be wrong, if she should see something that would show it wrong? She believes that dogmatically? Because the contrary to that is precisely what "tentative" means in that context: not dogmatic.

In any case, the "tentative" there wasn't even in reference to the "safe" beliefs like Polly's, but to the "risky" beliefs of someone who was testing a hypothesis rather than making tea. Can you not read more than half a sentence at one? -

Critical liberal epistemologyCome back to the basic point; Polly put the kettle on in order to make tea. She did not put it on in order to test an hypothesis. — Banno

I addressed exactly that difference in the last paragraph of the OP:

In general, I hold, we should tentatively adopt more specific and so risky beliefs when we can afford to risk being wrong, but when we cannot afford that risk, we should act in accordance with those beliefs that have the greatest probability of being true. — Pfhorrest

So sure if you're just trying to make tea, not test a hypothesis, then roll with the belief that's more probably correct, so you don't mess up your tea, even though you might possibly learn something by messing up your tea. -

Critical liberal epistemologyYour program wants to reduce induction to deduction. — Banno

It does not, and I have repeatedly said as much.

It just doesn't rely on induction for the task of differentiating between competing beliefs.

Induction is a fine way of coming up with beliefs. But induction on the same set of observations may come up with different beliefs. (And non-inductive processes may result in still other beliefs too). How then to choose between them? That's the issue at hand here.

Did you see this video I linked earlier?

Everyone there is using induction to come up with their hypotheses. All of their hypotheses are consistent with the data. But they're all different hypotheses. And they're all wrong, until someone finally catches on to try seeing what doesn't fit the data, and figures out the correct solution.

Also, you get that I'm not arguing against induction at all? The bit of my past post I just quoted ended, in case you didn't read to the end:

...pragmatically requiring us to always act as though they [things like induction] are true or else give up all hope of knowledge — Pfhorrest

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum