-

Analytic PhilosophyAs one of the people usually reverting people who fuck things up badly, I welcome anyone here to risk it.

It’s literally one click to fix anything you break, and if you stick around to talk to the people who revert it, you’ll probably stand a good chance of making improvements. “Be bold” is literally the first step of the normal wiki process (followed by reversion and discussion if there are any problems with your bold moves).

The more eyes the better, and WP philosophy articles have sadly few eyes on them. -

Analytic PhilosophyI think rather it’s the other way around: Continental philosophy is all contemporary philosophy not closely aligned with the Analytic tradition.

Anyway, nice to see Banno running with my half-thought-out idea from another thread. Wikiproject Philosophy really needs new blood. -

What do non-philosophers make of philosophy?Oh, I left out one thing I’ve anecdotally seen people take philosophy to be: psychology. Those people seem to think that philosophers/psychologists “must be really smart” be because “those subjects are hard”.

-

What do non-philosophers make of philosophy?I have the impression that most people don’t even know what philosophy is about. The traditional religious majority seem to think it more or less theology, new agers seem to think it’s all about reincarnation and crystals and shit, and most of the remainder seem to me to come from a place of scientism and dismiss it as either one of the above, or else reduce it to just ethics, which they may or may not think important or capable of truth.

That’s all just my impression though. I recently started a similar thread to find out what other people think most people think philosophy is about. -

Cogito Ergo Sum vs. SolipsismWhen Descartes doubt that everything but his mind exists, he is also doubting that you exist to be doubting that he exists: he does not experience your doubting, only his own. You of course think the same about him as he does about you. Assuming you both actually read exist, and follow from doubt to the rejection of each other’s existence, then you are both wrong. But not because your own beliefs are in contradiction with themselves: you each consistently conclude that you are the only mind, and that nobody else exists to be doubting their own existence, only you are doing that.

-

Cogito Ergo Sum vs. Solipsism2. Cogito ergo sum: I'm certain I exist AND I am an other mind to someone at least. — TheMadFool

This is the problem. The Cogito doesn't establish that there are other someones for whom I am an other mind. I'm only certain that I exist. If there are other minds like me, they're probably certain that they exist, but (with only the Cogito to go on) I am doubtful about that there are any such other minds to begin with.

If there are a bunch of different minds, all of them solipsists, then they are all in contradiction with each other. But if I start off doubting everything, including that there are such other minds, and I find certainty that I exist via the Cogito, then my picture of the world is still consistent with itself: it's of a world in which I am certain I exist and doubtful that anybody else does. I might be wrong, but not because I'm inconsistent with myself. -

An hypothesis is falsifiable if some observation might show it to be false.Maybe the problem isn't with the phrasing but with other wikipedians' reading comprehension.

If I have the time and inclination I might comment on the talk page myself.

In the mean time, here's a uselessly tautological definition:

Falsifiability is the ability to be shown to be false. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsIt's a welfare system. What they leave out is that it's mainly welfare for the corporate world, not the welfare queens. — Xtrix

That may be so, but that doesn't make it socialism. States protecting the welfare of the wealthy is the opposite of socialist. (And the commonness of that happening is one of the main complaints libertarian socialist have, who is against state socialism because, among other reasons, the state part just gets co-opted by the powerful and undos the socialism part; just like they're against libertarian capitalism because the capitalism part leads to de facto states and undoes the libertarian part).

That's not even fair to capitalism, either. — Xtrix

It's the definition of capitalism: where those who have greater wealth than others (specifically in the form of capital) use that difference to extract further wealth from those who have less than them (with which to acquire further capital and accelerate the process). It's not the definition of a free market, sure, but you seem to accept that "free market" is not a synonym for "capitalism".

He did give an argument for markets, but the argument was that under conditions of perfect liberty, markets will lead to perfect equality. That’s the argument for them, because he thought that equality of condition (not just opportunity) is what you should be aiming at. — Xtrix

Correct, which is why I think he would have been a libertarian socialist, had he lived to see socialism become a thing at all. The libertarian socialists who came after him have long been proposing solutions to the problem of why markets in practice haven't lived up to that theoretical ideal. (Spoiler warning: it's because states, including private armies bought by capitalist robber-barons, enforcing unlimited claims to property and power to contract, undermines the actual freedom of the market, so the solution is to stop the enforcement of those illegitimate claims and powers and let the market be truly free). -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsWhy not call it state socialism? — Xtrix

Because it’s not at all socialist? Where in any of this corporatism is ownership of the means of the production, or even the proceeds from it, being distributed to the people? Instead wealth is being concentrated in the hands of those who already have more of it, which is the opposite of socialism: capitalism.

You see my point -- "capitalism" and "socialism" are almost completely devoid of meaning at this point. — Xtrix

If so, that’s a product of Cold War era propaganda conflating them with command economies and free markets, respectively. Socialism is not opposed to free markets, just capitalism. Free markets are not opposed to socialism, just command economies. You can have state capitalism, and libertarian socialism, and it’s just the statists and capitalists who want you to believe otherwise.

The reality is that our economy is designed to favor concentrations of power -- whatever you call it, it's not what Adam Smith had in mind. — Xtrix

That’s true. Adam Smith never advocated capitalism, just free markets. He probably would have been a libertarian socialist if he had lived to see socialism become a thing. Capitalism seems the opposite of what he expected free markets to create. -

Did Descartes prove existence through cogito ergo sum?Descartes thought he proved the "I" part, and that's the usual interpretation.

Others have disputed that since then.

I think that to the extent that he proved the existence of the self, he also proved the existence of some world: whatever the subject and object of the thought are. (Which could potentially be the same thing, but aren't necessarily). -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsIt would help if we had a capitalist system to begin with, but we don't. In any meaningful sense. It's a corporate nanny state economy. — Xtrix

That's a kind of capitalism, it's just state capitalism, which is the worst of both worlds.

It's a lot like Clinton in '16. I remember all the celebrities coming out trying to stoke the crowds, pushing the "first woman president" thing, and from what I saw it nearly always fell flat or else looked so contrived as to be embarrassing. — Xtrix

And it seems like he should have even worse odds than Clinton in '16, because women I know who were excited about Clinton despite her not being very exciting for policy reasons, just because she was the possible first women president, are all rolling their eyes and sighing about the possibility of Biden, yet another old white man. Of course, they're also equally unenthusiastic about Bernie, yet another old white man, despite the drastic policy differences between them. Sigh. Tribalism makes me sad. -

Cogito Ergo Sum vs. SolipsismIt's the simultaneous doubt about and certain knowledge of the existence of our minds that's the problem. — TheMadFool

Doubt and certainty are epistemic, and so relative to each thinker. Each thinker has certainty about their own mind's existence and doubt about all other minds' existence. So each thinker finds themselves concluding that they are the only mind that exists. It's only from our non-solipsistic perspective, assuming that all of these bodies we see talking about this stuff, all have minds inside them like ours, that we can talk about this kind of thing. From any individual solipsist's point of view, theirs is the only point of view, so whether "other people" would find themselves certain of their own existence is irrelevant, because that solipsist doubts that any "other people" exist to begin with. A figment of my imagination can't be certain of its existence, because it doesn't have a first-person point of view to think the cogito from. So if "everyone else" are all figments of my imagination, the cogito doesn't prove anything about their existence. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsGiven that Sanders and Biden are the top two Democratic candidates, and my expectations that Biden would lose against Trump while Sanders would win, I'm predicting that Bernie's success in the Democratic primaries is pretty much equivalent to Democratic success in the general election. And since Biden is leading the primary polls... I'm sadly expecting a Trump victory in the general.

-

Cogito Ergo Sum vs. SolipsismThe cogito only claims to establish the existence of the mind of the one doing the thinking. It has nothing at all to say about the existence of other minds having thoughts that the "I" thinking the cogito is not the thinker of. So if you're in a place of doubting the existence of everything, the cogito only saves you from doubt in your own existence. Other minds, if they exists, cannot doubt their own existence, but they could doubt yours, and each others', and so you can doubt theirs too.

-

How much philosophical education do you have?Surprised to see that even three months later there's not a single person with an associate's degree here.

-

What do people think philosophy is about?I'm surprised that most of the options have received no votes at all so far. I especially expected that "religious stuff" and "political stuff" would be higher.

Maybe I shouldn't have put an "other" option. Philosophy polls probably shouldn't even have an "other" option, because every philosofan thinks they're a special snowflake with unique uncategorizable opinions. -

An hypothesis is falsifiable if some observation might show it to be false.I think you misunderstood. I'm saying to add the "if it is false" to the definition in the OP: "An hypothesis is falsifiable if, if it is false, some observation might show it to be false". Because people seem to be objecting to the definition in the OP on the grounds that "some observation might show it to be false" is only true of hypotheses that are actually false, and so rules out hypotheses that are true from being falsifiable.

All of that sounds like just someone has reading comprehension problems, to me, so I think maybe explicitly adding the "if it is false" part could clear things up for them. -

An hypothesis is falsifiable if some observation might show it to be false.Besides the indefinite article, it sounds straightforwardly correct to me, but if people are being so dense as to not understand it, maybe couch it in a conditional: "if it is false, there is some observation that can show it to be false".

-

Are the thoughts that we have certain? Please help clarify my confusion!More or less. It's certain that thinking is happening, and that something is thinking, and something is being thought about. That last bit seems to be your main point.

-

On deferring to the opinions of apparent expertsWikipedia is not really the place to go for the latest breakthroughs, because it's meant to be a tertiary source, which means a secondary source needs to have first vetted the notability and reliability of the primary sources, which takes time. Someone who just published a paper can't immediately add their results to Wikipedia (I mean, they can, but they'll be reverted); some journal or news source first has to look at their paper and say it's important and largely regarded as correct, and then someone (not the original researcher) can add something to the wiki citing that journal.

Also, since every claim in Wikipedia besides things like "the sky is blue" are supposed to be cited to reliable sources, there's really no reason to ever cite Wikipedia directly: just cite whoever it cites instead. If a claim in a wiki article doesn't cite a more reliable source, then maybe that particular claim isn't so reliable, and probably shouldn't be cited in something that's supposed to be professional.

But in a casual conversation like this, Wikipedia is generally very reliable, especially about anything big and contentious, because anyone who disagrees with a claim will fight to remove it and whoever has the best reliable citations to secondary sources will win. -

Are the thoughts that we have certain? Please help clarify my confusion!My take is to abstract even more from thinking, to experiencing (thinking is a kind of experience), and say that "experience is happening" is the greatest certainty; "something is experiencing" and "something is being experienced" are the next greatest certainties, which we call the self and the world, though we don't yet know if those aren't the same thing (that the self might be all of the world). Everything else is first sorting out what kinds of (combinations of) experiences are(n't) possible, and thus what is(n't) necessary about the world and oneself; and then filling in the details about those contingent possibilities, which is the long hard work of the empirical sciences.

-

Help with Introduction to PhilosophyI was also thinking of recommending that in addition to the rest.

-

Help with Introduction to Philosophy

To get a broad acquaintance with the history of the field and its range of thoughts, I think these are probably the most important authors to read:

Socrates (via Plato)

Plato

Aristotle

Aquinas

Descartes

Locke

Kant

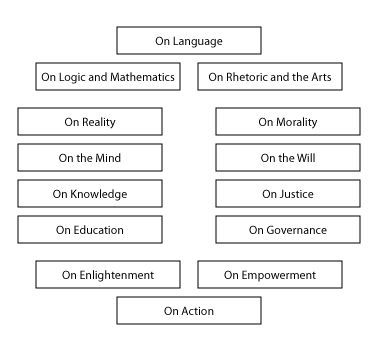

I recommended these guys because in the history of philosophy, there is a tendency for there to be periods of two opposing camps or trends or schools, and then one philosopher or school of philosophy to unite them, and then two new opposing schools to branch off from that again, back and forth like that. These authors give an overview of those opposing schools, and the figures who united them and from whom new ones were formed, as illustrated here:

We don't have a lot of material from Thales, the other Ionians, or the Italiotes (collectively the Presocratics), and their work was really primitive and not super relevant today, so I skipped them entirely. Socrates is really where philosophy as we think of it begins, and his student Plato and Plato's student Aristotle were the founders of the two main opposing schools during the Classical period of philosophy. In the Medieval period things were largely reunited into one school, the Scholastics, of whom Thomas Aquinas is the preeminent figure. The Modern period began with Rene Descartes, the first of what would come to be called Rationalists, and their opposing school, the Empiricists, got their beginning with John Locke. Then Immanuel Kant once again reunited philosophy, until it split again into this Contemporary period's still-unreconciled divide between Analytic and Continental schools, who are too numerous and recent and ongoing to pick preeminent figures for. So that's why I recommend those authors for a historical overview.

Your school probably has courses on each of these guys, and you'll probably be required to take at least a few of them as part of your major. If you have time, two other Modern-era philosophers who I found very interesting and helped expand my worldview a lot are the empiricist George Berkeley and the rationalist Baruch Spinoza, who both have very unusual pictures of the world but ones I think have valuable ideas to contribute.

And then you should acquaint yourself with the foremost thinkers in the fields of:

Philosophy of Language

Philosophy of Art

Philosophy of Mathematics

Ontology / Metaphysics

Philosophy of Mind

Epistemology

Philosophy of Education

Philosophy of Religion

Metaethics

Philosophy of will

Ethics (especially utilitarians and deontologists)

Political philosophy

Existentialism / “philosophy of life”

Your school probably has a class on each of these too (except maybe the last), and you'll probably be required to take at least some of them anyway.

I think these give a thorough overview of the range of topics philosophy discusses, which all inevitably interrelate with each other. At the most abstract is philosophy of language, and two only slightly less abstract fields that are kind of opposite one another, philosophy of mathematics and philosophy of art. I missed all of those in my formal education and I regret it.

Instead I focused on the two halves of what I'd call core philosophical topics, roughly ontology and epistemology on one hand (about reality and knowledge), and ethics on the other hand (about morality and justice), which I would subdivide into fields analogous to ontology and epistemology (that are also roughly related to utilitarianism and deontology, hence why I emphasized those in particular) but that's not standard practice so I won't go into that here. Metaethics is an especially important part of ethics that ties in closely to philosophy of language, so I recommended that in particular.

Philosophy of mind ties in really closely with ontology and epistemology, and I think free will fits into a similar place regarding ethics because of the connection between free will and moral responsibility. Political philosophy has its obvious connections to ethics as well, being in essence the most important practical application of ethics, and though there doesn't seem to be a single established field that's perfectly analogous to it in relation to ontology and epistemology, I've found significant parallels in both philosophy of education and philosophy of religion, so I recommend those as well.

And lastly, the biggest thing that I overlooked in my formal philosophical education, opposite those abstract fields at the start, is the practical application of philosophy to how to live one's life meaningfully, which Continental schools like existentialism and absurdism address. This topic doesn't seem to have its own name, that I'm aware of, but I colloquially refer to it as "philosophy of life".

The bottom part of this illustration from my philosophy book illustrates the structure I think these fields have to each other:

For these purposes you can ignore everything above Metaphilosophy on that chart, as those are particular views of mine and not philosophical topics (this is actually a chart of the structure of my book, the latter part of which is structured after this same array of topics).

Speaking of which, add Metaphilosophy to my list of fields worth studying if you have room to squeeze it in. What even is philosophy, what is it trying to do, what constitutes progress at doing that, how can we do it, what does it take to do it, who should do it, and why does it even matter? -

What do people think philosophy is about?Those who want to believe will do so and those who don't, won't believe — Wittgenstein

I get what you mean, but I don't think it's so simple as that. A year ago I was so fraught with existential dread and angst that I found myself searching for anything I could think of that would just make me stop feeling that, including trying to turn to religion after a lifetime of irreligiosity. I wanted to believe... but I couldn't find any arguments that I didn't immediately see holes through, so I couldn't convince myself no matter how I tried. -

Defining Love [forking from another thread]Activity-passivity is basically one of the dimensions of that spectrum, and hate and fear are on opposite ends of it, but the same end of the positivity-negativity dimension.

I didn't mean to suggest that you could love and hate at the same time, as on this account love is "active-positive" and hate is "active-negative" (while tolerance is "passive-positive" and fear is "passive-negative"). Though now that you bring up that possibility, that does seem to be a thing that happens in real life, as in for example anxious-ambivalent attachment. I don't really know how to account for that yet on this model.

Someone else upthread suggested that "tolerance" is not really the right word for the opposite of "hate", and your use of "passivity" for one end of the second dimension of the spectrum makes me reflect on that. I'm still not sure what the best word would be, but I'm thinking something in the direction of "acceptance" or "welcoming", but more positive than that: the feeling of passively waiting and hoping that something good comes to you, as opposed to actively going after it yourself, which I've labelled "love". -

Karl Popper's Black RavensI've been noticing that (it's on my watchlist) and wondering if it was just a coincidence that that was happening there right as these conversations were happening here.

It would be kinda neat to see some kind of cross-collaboration between a forum like this and Wikipedia. Use Wiki as a reference to answer questions here (since WP:NOTFORUM), and then use the conversations here to inspire development of articles there. -

Is philosophy dead ? and if so can we revive it ?But saying "to any given question", this opens philosophers up, it makes them vulnerable to ridicule. — Pussycat

How so? Pursuing some question may be ridiculous, but philosophy is just about finding ways to pursue questions, not about picking which questions to pursue.

What does running want? An activity isn't the kind of thing that has wants. It's a means. Why run? To get somewhere fast, or for exercise maybe. Why do philosophy? I already answered that.But what of philosophy? What is its agenda? What does philosophy want? — Pussycat -

Hempel, Popper, Unicorns & GodNB that I’m not trying to argue for falsificationism here (though I do support it), just clarifying what it is and how it’s related to Hempel’s paradox. Hempel was not a falsificationist but a “hypothetico-deductivist” (which became the standard type of confirmationism, before “confirmationism” was a word).

-

Hempel, Popper, Unicorns & GodThe issue isn't that R2 supposedly contradicts R1. Nobody thinks it does, not even Popper.

Popper's whole falsificationist program is saying that "confirmatory evidence" is no evidence at all. Only disconfirmatory evidence counts. That's why it's "falsificationism", the opposite of "confirmationism". It's explicitly anti-confirmationist.

There are more reasons to be anti-confirmationist than just this, but Hempel's paradox illustrates a problem with confirmationism. It's absurd to think that green apples tell you anything about the relationship between ravens and blackness. But because R2 = R1, it's equally absurd to think that black ravens tell you anything about the relationship between ravens and blackness. Falsificationism points out what's wrong with both of those things: they take evidence to confirm a hypothesis, when it can do no such thing. It can only falsify it.

Observing 3 black ravens would suggest a pattern viz. R1 = all ravens are black. — TheMadFool

Popper would say no, it doesn't. Well, maybe it suggests it, in an entirely non-rigorous way -- maybe seeing three black ravens gives someone the idea that maybe all ravens are black -- but it doesn't provide any evidence for it, on a falsificationist account. On a falsificationist account, you can come up with the idea that all ravens are black out of wherever you come up with it, even if you've never seen a raven, and its status is "maybe possible". Then you find a black raven... and that doesn't change its status. Then you find another black raven... still no change. You can find as many black ravens as you want and that tells you nothing at all about whether or not all ravens are black: it's still a possibility, but it already was a possibility. It's not until you find a non-black raven that anything changes. -

Hempel, Popper, Unicorns & GodObserving green apples, red tomatos, etc. i.e. non-black non-ravens doesn't falsify the claim R1 because these observations don't falsify claim R2 and R1 is equivalent to R2. If so, then R1 remains unfalsified ... — TheMadFool

Correct so far.

... and should be, if there are direct confirmatory observations e.g. a considerable number of black raven observations, considered as a scientific claim - true for all intents and purposes. — TheMadFool

Not so correct according to a falsificationist like Popper. A claim being scientific has nothing to do with whether it is true or not: there can be false scientific claims, like for example Modified Newtonian Dynamics as a theory of dark matter is pretty much known to be false now (because of the Bullet Cluster observation), but it's still a scientific claim. That's because it's falsifiable: if it were false, we could show that it was false (and in this case it is, and we have).

Most importantly, the falsificationist says that that "if there are direct confirmatory observations e.g. a considerable number of black raven observations" part means nothing. Finding a whole bunch of black ravens tells us nothing at all about whether all ravens are black, according to the falsificationist. And likewise finding a whole bunch of non-black non-ravens tells us nothing at all about whether all non-ravens are non-black. That's the key point of falsificationism: you cannot confirm things. Failing to falsify things still isn't confirming them. Every hypothesis starts off with the status of "possible", and then either keeps that status, or loses it if it's falsified. A bunch of failed falsifications never boosts its status higher than the initial status of just "possible".

So on a falsificationist account, finding a non-black non-raven has no impact on the likelihood of all ravens being black -- as we'd expect. That comes at the "cost" of the implication that finding a black raven also has no impact on the likelihood of all ravens being black. But that cost, the falsificationist argues, is much less; it's a little unintuitive, because we have confirmationist intuitions, but it's much less unintuitive than green apples proving that all ravens are black, and more importantly much less logically problematic than confirmationism, since that's just straightforwardly a case of affirming the consequent (as it's trivially fallacious to argue "if P then Q; Q; therefore P"). -

Is philosophy dead ? and if so can we revive it ?What is philosophy's purpose? — Pussycat

The pursuit of wisdom. Wisdom, in turn, does not merely mean some set of correct statements, but rather is the ability to discern the true from the false, the good from the bad; or at least the more true from the less true, the better from the worse; the ability, in short, to discern superior answers from inferior answers to any given question.

To that end, philosophy must investigate questions about what our questions even mean, investigating questions about language; what criteria we use to judge the merits of a proposed answer, investigating questions about being and purpose, the objects of reality and morality respectively; what methods we use to apply those criteria, investigating questions about knowledge and justice; what faculties we need to enact those methods, investigating questions about the mind and the will; who is to exercise those faculties, investigating questions about academics and politics; and why any of it matters at all.

The tools of philosophy can be used against that end, but I prefer to call that "phobosophy" instead. -

On deferring to the opinions of apparent expertsLook, why don't I just draw you a unicorn and you can colour it in? — Bartricks

Can I color it both pink and invisible? -

Is philosophy dead ? and if so can we revive it ?I think philosophy is much like martial arts for the mind: as the practice of martial arts both develops the body from the inside and prepares one to protect their body from attacks from the outside, both from crude brutes but also from more sophisticated attackers who would twist the methods of martial arts toward offense rather than defense, so too philosophy develops the mind and will from the inside, and also prepares one to protect their mind and will from attacks from the outside, both from crude ignorance and inconsideration but also from more sophisticated attackers who would twist the methods of philosophy against its purpose.

In a perfect world, the latter uses of either martial arts or philosophy would be unnecessary, as such attacks would not be made to begin with, but in the actual world it is unfortunately useful to be thus prepared; and even in a perfect world, with no external attackers, martial arts and philosophy are both still useful for their internal development and exercise of the body, mind, and will. -

Hempel, Popper, Unicorns & GodNobody is saying black things EQUAL ravens. Black things are a SUPERSET of ravens; at least, that's the claim in question. That claim might be false; if a bloody red wounded raven counts as a non-black raven, then it is false. That's not the point.

"All ravens are black" is just an example of a hypothesis. Substitute what ever other terms you want. Pick some A and B such that maybe all B are A. It doesn't matter what you pick. If all B are A, then all non-A are non-B. So if you find something both non-A and non-B, that would count as evidence for "all non-A are non-B" just as much as finding something both B and A would count as evidence for "all A are B". And since those are equivalent, the non-A and non-B thing would count as evidence that all B are A. Which is absurd. So we shouldn't make inferences like that. -

Hempel, Popper, Unicorns & GodTake a look at this image:

Everything in B is in A. Everything that is not in A is also not in B. Right? Obvious.

B = ravens and A = black things. Everything that's not black is also not a raven, because if it was a raven, it would be black.

That part isn't weird at all. That's just straightforward logic and sets.

The weird part is that if we think finding a black raven counts as evidence for "all ravens are black" (P), then finding a non-black non-raven (like a green apple) should likewise count as evidence that "all non-black things are non-ravens" (Q). But sentences P and Q are equivalent -- both sentences paint the same picture, like that one above -- so evidence for Q is the same thing as evidence for P. Which would mean a green apple is evidence that all ravens are black, if we accepted that we could make inferences from particulars to universals like that.

Which suggests that we shouldn't accept that we can make such inferences. A green apple, despite being a non-black non-raven, isn't evidence that all non-black things are non-ravens. A black raven, likewise, is not evidence that all ravens are black. No number of non-black non-ravens can prove that all non-black things are non-ravens, and no number of black ravens can prove that all ravens are black. You can't positively prove (or confirm) anything.

But you can disprove (or falsify) them. A single non-black raven would disprove both P and Q. -

Hempel, Popper, Unicorns & GodThe fact that a raven is black doesn't mean mathmatically all non-black things are Non-ravens. — Qwex

It does. We can symbolize "all ravens are black" as "R -> B". That's equivalent to "~(R ^ ~B)" or "~R v B" or "~B -> ~R", which we would say as "nothing is both a raven and non-black", "everything is either not a raven or black (or both)", and "everything that is not black is not a raven", respectively.

You're misunderstanding the relationship between Popper and Hempel. Popper uses Hempel's paradox as a disproof of confirmationism, not as a consequence of falsificationism. Hempel's paradox only follows from confirmationist inference, and the absurdities it leads to are a reason Popper gives to reject confirmationism, leaving falsificationism instead.

You're correct that under a confirmationist view, the non-existence of unicorns would be reason to believe the existence of God. And that is absurd. Which is why you should reject confirmationism, like Popper does. -

Karl Popper's Black RavensI find the logical niceties tortuous at times (like this paradox - what could the status of a non-raven entity ever add to the knowledge of ravens?). — Pantagruel

It couldn't, which is the point. Confirmationism implies that it could, which is absurd, hence disproving confirmationism. -

Karl Popper's Black RavensThe statement, all cats are animals is falsifiable precisely by looking for and finding a non-animal that's not a cat. — TheMadFool

Nope, it's falsifiable by finding a non-animal that is a cat.

"All cats are animals" = "if cat then animal" = "not (cat and non-animal)"

To falsify it, you have to find the negation of that, which would then be "cat and non-animal". -

Karl Popper's Black Ravensfalsification theory (hypothetico-deduction — bongo fury

Hypothetico-deduction is confirmationist, not falsificationist.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum