-

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because..."P-zombie" is an incoherent construct because it violates Leibniz's Indentity of Indiscernibles without grounds to do so. To wit: an embodied cognition that's physically indiscernible from an ordinary human being cannot not have "phenomenal consciousness" since that is a property of human embodiment (or output of human embodied cognition). A "p-zombie", in other words, is just a five-sided triangle ... — 180 Proof

And yet it is still true that no geometric figure is a five-sided triangle, and so that all geometric figures have the property (consistency of sides or however you want to formulate it) that five-sided triangles would lack. That's just a completely trivial property that, because everything has it, doesn't meaningfully distinguish between anything.

I keep saying that I'm not claiming that, I'm not talking about that sense of "consciousness" at all (although I agree that that is the important sense of "consciousness", it's just not the topic of this thread). If you're going to keep thinking I'm saying something I'm not, despite repeatedly saying that that's not what I'm talking about, I'm going to stop trying to say it.What evidence - fundamental physical law - shows that every physical thing cognitates (i.e. reflexively processes information, or adaptively behaves/moves/transforms itself)? — 180 Proof

Did you read the last paragraph (the addendum) of my last post?

It is defined that way, as independent of any particular functionality. I didn't make that definition. I don't think the thing that is defined that way is important. I think it's trivial. But philosophers talk about it, and this thread is explicitly about it, and my take on it is that it's a trivial thing that everything has and doesn't distinguish between anything, and so not worth saying anything more about it. Instead, we should talk about access consciousness for all the interesting philosophical discussion. You seem to want to say that only access-conscious things are phenomenally conscious, and I think that that gives too much importance to phenomenal consciousness, makes it something that does actually distinguish between things, except that it just so happens to correlate with access consciousness somehow, so that distinction becomes entirely redundant.What evidence is there that "phenomenal consciousness" is anything other than (the) output, or function, of a nonlinear dynamic process? — 180 Proof

Instead of just saying "phenomenal consciousness is trivial, what matters is access consciousness" like I do, what you're saying would imply that, in addition to (something along the evolutionary chain between rocks and) humans gaining access consciousness that distinguishes us from rocks, also at that same moment something became metaphysically different about (that important step along the evolutionary chain between rocks and) humans. I'm saying nothing metaphysically changed along the way; all that changed was the functionality of the systems in question. Whatever is metaphysically necessary for that (ordinary physical) functionality to produce human consciousness, that was already present in the components that humans are made of. And it is consequentially a trivial thing that's not worth talking about, and I'm getting tired of talking about it. -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...I'm not saying that first-person experience is something like mass or charge, so if you think that's what I'm talking about when arguing against my position you're arguing against the wrong thing. I'm also 100% on board with the important thing about "mind" being the reflexive information-processing function you're talking about; but do you understand that that kind of reflexive functionality is, definitionally, "access consciousness", the topic of the "easy" problem of consciousness, and not at all what the "hard" problem of consciousness is talking about? I think you and I agree completely on that topic, and I'm not trying to talk about it at all here. I'm trying to talk about the thing philosophers call "phenomenal consciousness", which is a different thing. (See Ned Block, or Wikipedia on Types of Consciousness).

A philosophical zombie would be, by definition, something that has all of that reflexive information-processing functionality, but is missing "phenomenal consciousness". I'm saying that things like philosophical zombies can't exist, because you can't be missing that, because everything necesssarily has it; and saying that everything has it isn't imputing anything of any substance to the likes of rocks, but rather saying that this "phenomenal consciousness" is something so completely trivial that even rocks have it, and it doesn't usefully distinguish anything from anything else. To say, instead, that nothing has phenomenal consciousness, would be to say that we are all philosophical zombies. Obviously (to each of us) we are not (ourselves) philosophical zombies, which leaves either the possibility that there is something substantial to this "phenomenal consciousness" thing that distinguishes philosophical zombies from real humans, something that rocks don't have but humans do, which comes into being somewhere in the evolution from one to the other, but is (definitionally) not just a functional property like the reflexive information-processing stuff you're talking about (that's access consciousness, not phenomenal consciousness); or else that whatever it is that's supposed to distinguish humans from philosophical zombies is an absolutely trivial thing that doesn't distinguish anything from anything, so since humans (definitionally) have it, so does everything else.

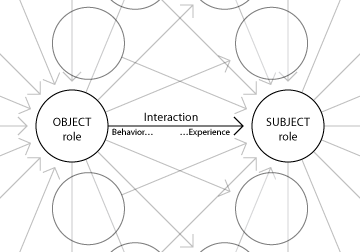

ADDENDUM: Maybe this will be a more amendable way to phrase it. You take consciousness (I'm intentionally not specifying which kind here because you don't seem to be) to be all about this reflexive information-processing ability. I agree that the reflexivity and the more complex processing parts of that are the important parts of access consciousness, and that that complex functionality can weakly emerge from things that don't have it yet. But the "information-processing" part in general doesn't suddenly spring into being; everything all the way down is capable of processing information, at some level. The whole universe can be seen as informational signals passing around between things, and those things can be defined by their function in that network of signals, the way they output signals in response to the signals input into them. Information processing in general doesn't emerge from stuff with no information-processing ability; just more and more complex patterns of information processing emerge out of simpler forms of it. I take "phenomenal consciousness" to be equivalent to that fundamental information-processing ability that everything has, which in most cases is completely unremarkable; most signals are just passed along or rerouted or minimally transformed by the functions of the simplest of things, and it's only in the aggregate of a whole bunch of those simple particles interacting in really complicated ways that more complex functions emerge. But the basic role of taking information in ("experience") is as fundamental to everything in the universe as the role of sending information out ("behavior") is; they're two sides of the same coin. -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...So we can't really even say what a physical thing is, other than in a common-sense way. But as we're dealing here with foundational definition of what constitutes the nature of being, then does declaring that there are 'only physical things' say anything beyond your adherence to physicalism? — Wayfarer

I gave my definition of what a physical thing is in the bit that you quoted. But yes, when it comes down to it, saying that something is or isn't physical really says very little at all, because on such a definition, being nonphysical is the same thing as being unreal: it's being somehow wholly disconnected from the web of interactions that constitutes reality (on my account). Being a philosophical zombie is likewise incoherent, for the exact same reason: to have no phenomenal experience would be to be completely disconnected from that web of interactions, just seen from the subjective side of those interactions rather than the objective side.

(As an aside, you know that "physical" is broader than "material", right? I'm actually against materialism, in a certain sense of the word, the sense that George Berkeley was against. But even as a subjective idealist, Berkeley still considered himself a physicalist).

That wasn't what I was saying there, but I do say something like that. What I was saying was that the events that communicate the impact of the stone to the person it hits, the exchanges of photons between the electrons of the stone and the electrons of the person's body that transfer momentum and energy and so on between them, are the same events that constitute the raw phenomenal experience of the person of being hit by the stone.However, surely you can't be saying that stones experience the hitting of a human subject. — Wayfarer

Those interactions also have a flow of information and energy back the other direction too, so there is also a raw phenomenal experience the stone has of hitting the person. But beyond that most superficial level the experiences of course differ immensely. The person is a complicated system with lots of complex self-interaction happening all the time, so in addition to the brute impact of the stone, the person also experiences themselves reacting to the impact of the stone, and then other parts of themselves reacting to those reactions, in a complex cascade of biological and psychological events, all of which contribute to the overall experience the person has of being hit with a rock. The rock of course has no such complex self-interaction; it doesn't experience itself experiencing the impact, it just automatically, mechanically responds to the experience with a very simple behavior (it changes its velocity) and that's it. It's that difference in the complex internal self-interaction that makes human experience noteworthy; not just the brute having of any experience at all.

The fundamental point about beings, as distinct from inanimate objects, is that they are demonstrably subjects of experience, whereas there is no grounds for asserting that with respect to stones and other objects. — Wayfarer

I find this distinction you're making between "beings" and "inanimate objects" dubious. A being is just a thing, an object, an entity, a think that bes, or as we say in English, is. -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...That's not what I was saying there, though I do agree with something more-or-less similar to that. (To fully agree with that, all of the internal behavior, the functional goings-on in the robot's equivalent of a brain, has to be the same too. Not just something that can mimic the gross motor actions of a person.)

What I was saying there is roughly that "to do is to be" and "to be is to do" (a thing's existence consists entirely in what it does, all of its properties are dispositions to act upon observers in certain ways) and "to be is to be perceive[able]" (a thing's existence consists entirely of its its observable properties) are different ways of phrasing the same statement, because for a thing to be "perceived" (more technically observed or sensed; perception is something more than that in contemporary terminology) is for it to act upon the observer. What's actually going on is an interaction between two things, and that same interaction constitutes both the behavior of the one thing upon the other, and the experience the other thing has of the first thing.

-

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...if what two different names refer to is the same individual, then they necessarily have the same reference. — Janus

I think the confusion here might be about what this quoted bit means. I suspect you are trying to say:

[](two names refer to the same individual -> those names have the same references)

But what I've been hearing (and I'd argue is the more literal reading of your words) is:

(two names refer to the same individual) -> [](those names have the same references)

Kripke isn't saying it's necessary that "Batman" and "Bruce Wayne" refer to the same individual; it's possible for them to refer to different individuals. But [](Batman = Batman), and [](Bruce Wayne = Bruce Wayne], and if those should happen to be the same individual, then [](Batman = Bruce Wayne], because every individual is necessarily identical to themselves. The assignment of meaning to words is contingent; the identity of an individual to itself is necessary. The words don't necessarily mean the same thing, but when they do mean the same thing, the things meant by them are necessarily identical to each other because the things meant by them are just one thing. -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...This just says that if two names refer to one person then inasmuch as they do refer to that one person, they do so necessarily. — Janus

Not quite. The necessity isn't about what the names refer to. The necessity is the identity of "two" individuals, who are actually one individual under two different names. If the Morning Star is Venus, and the Evening Star is Venus, then the Morning Star necessarily is the Evening Star because Venus is necessarily Venus. But it's possible that "Morning Star" or "Evening Star" might be used to refer to something other than the same planet, Venus; the fact that those words mean those things is contingent, and a posteriori, though still analytic because it is about words. -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...What exactly was it you were applauding in this post that is different from anything I've said that you've been arguing against since? I've just been rephrasing the same thoughts since then and for some reason it seems you heartily agreed the first time and have disagreed ever since.

To answer your latest question, panpsychism is not supposed to be a "conjecture about the world of facts", the likes of which should be testable; most philosophical claims are not the kinds of things meant to be testable, they're ways of thinking that are more or less useful as part of the framework within which we think about the kinds of things that are testable. But as for an argument for it, I'll just try rephrasing the same thing I've been saying over and over again, in more detail:

There are three exhaustive possibilities when it comes to what things have any first-person experience at all, where that having of a first-person experience at all is what is meant by "phenomenal consciousness", which is the topic of the "hard problem of consciousness". Either:

-Nothing at all has it, not even humans; or

-Some things don't have it, but other things do (and if there is ultimately only one kind of stuff, which doesn't have it in its simplest form, then somehow that stuff can be built into things that somehow do have it); or

-Everything has it.

The first of those three options ends up telling people that no, they really don't have any first-person experience at all, which is prima facie absurd. I think thought experiments like Mary's Room also show the significance of first-person experience apart from third-person experience, though I don't think that that disproves physicalism like it claims to.

The second option raises this big thorny problem of figuring out exactly where in the process first-person experience comes into being, and whether things like philosophical zombies could be possible, something that is exactly like a human being except that it lacks this having of a first-person experience, since on this (second option) account it's possible for some things to not have it while other things do.

The third option dissolves that big thorny problem of the second option, without falling into the absurdity of the first option. Since (as you've elsewhere agreed) philosophy is all about dissolving illusory problems, that makes this third option the best philosophical answer to the "hard problem of consciousness".

But that only means that there isn't anything wholly new popping into being from whole cloth at any stage of development between quantum fields and human beings. What's going on in human beings is built out things that are going on in the stuff human beings are made out of. New, more complex forms of the same general kind of stuff can still arise, weakly emergent, from simpler forms of that same general kind of stuff. I think that the mere having of a first-person experience at all, "phenomenal consciousness", is completely trivial, and trying to figure out where it starts and ends is a useless quagmire. What matters is the functionality of a thing, which can be seen both in the third person through its behavior, and in the first person (by the thing itself) in its experience. That functionality, and with it features of both the behavior and the experience of the thing, can emerge (weakly) from simpler functionality of things the thing is made of, but at no point does there start or stop being any first-person experience at all, the quality of that experience just changes, enhances or diminishes, just like the mechanical behavior of the thing does.

In another post recently I wrote this really nice little summary of my whole view on this topic that I'll copy and paste here:

I think there are only physical things, and that physical things consist only of their empirical properties, which are actually just functional dispositions to interact with observers (who are just other physical things) in particular ways. A subject's phenomenal experience of an object is the same event as that object's behavior upon the subject, and the web of such events is what reality is made out of, with the nodes in that web being the objects of reality, each defined by its function in that web of interactions, how it observably behaves in response to what it experiences, in other words what it does in response to what is done to it.

In an extremely trivial and useless sense everything thus "has a mind" inasmuch as everything is subject to the behavior of other things and so has an experience of them ("phenomenal consciousness", the topic of the "hard problem"), but "minds" in a more useful and robust sense are particular types of complex self-interacting objects, and therefore as subjects have an experience that is heavily of themselves as much as it is of the rest of the world ("access consciousness", the topic of the "easy problem"). -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...The problem with this notion of rigid designation is that 'Bruce Wayne' can be a name for more than one individual, and only one of those individuals is also Batman; so it is not necessarily or "analytically" true that Bruce Wayne is Batman. — Janus

I was just saying that that kind of thing, not what OmniscientNihilist was calling "omniscience", is what analytic a posteriori knowledge is about.

But to defend Kripke, what you are saying is that it is not necessary that names "Bruce Wayne" and "Batman" refer to the same individual; those words can be used to refer to other people besides that one individual we're talking about. That is true, but Kripke's point is that that individual (the one we're talking about) is necessarily identical to himself, like all individuals are, and so if that is the person being referred to by both the names "Bruce Wayne" and "Batman", then it is necessarily true that Bruce Wayne (the "Bruce Wayne" we're referring to) is Batman (the "Batman" we're referring to); but we cannot know a priori that those names are used to refer to the same individual, we learn who those names are used to refer to (and that they're used to refer to the same person) a posteriori. This is a kind of analytic knowledge, because it's about the meaning of words; but not all analytic knowledge is a priori.

For another example: the classic example of a necessary, a priori, analytic truth is that "all bachelors are unmarried". But that hinges on the meanings of "bachelor" and "married". And we acquire the knowledge of what those words mean a posteriori. That "bachelor" means "unmarried man of marriageable age" is an analytic a posteriori (and contingent) fact; that bachelors (meaning unmarried men of marriageable age) are unmarried is an analytic a priori (and necessary) fact. -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...Analytic a posteriori is like what Kripke talks about in "Naming and Necessity", e.g. about how it's necessarily true that Batman is Bruce Wayne, because those are just names for the same person, but we can't work out that truth with a priori reasoning, because we have to learn from the outside world that those are two names for the same person. It's about words, so it's analytic, but it's a posteriori, known from the outside world: it's about knowing what words mean, which we learn from observing other people using them.

-

Stoicism: banal, false, or not philosophy.While I mostly disagree with Bartricks here, I think there is at least a similar point to be made about how the original Stoics had a metaphysical view that was supposed to give reason for adopting their now-eponymous demeanor, and that metaphysics is quite contestable now, requiring some other reason be given in place of it (or else the conclusion be rejected) if you don’t accept that metaphysics.

-

What’s your philosophy?Thanks for the applause. :)

The Institutes of Knowledge

What is the proper educational system, or who should be making those descriptive judgements and how should they relate to each other and others, socially speaking? — Pfhorrest

Freethinking proselytism is what I'm calling this, though I'm hesitant about that "proselytism" as a name for what I mean. I mean that education should be non-authoritarian, but it should also be non-secret; it should be collaborative, knowledge should be spread and shared, but it should not be forced on anyone. I think of this as the epistemic analogue of libertarian socialism, as this question is roughly the epistemic analogue of the question about governance; irreligious education is like stateless governance, and "proselytism" for lack of a better term, the sharing of knowledge and the lack of mystery about the truth, is like socialism inasmuch as that means roughly a kind of sharing of wealth, and there can be irreligious (freethinking) proselytism just like there can be stateless (libertarian) socialism.

Within such a freethinking educational structure, I think the system we already have in the western world, of primary research feeding into secondary peer-review journals and those into tertiary textbooks and encyclopedias is already the correct "legislative" branch of such "epistemic government". The analogues of the executive and judicial branches of government are teaching and testing, and I think that all three of those should be kept separate from each other just like the separation of powers in government: those who write the textbooks, those who teach their contents, and those who test students on their comprehension of them should be separate parties, so that no one party has epistemic authority to just tell the students what is true without anyone to check them. The testers should also, I think, fill a role like the religious role of a pastor, being a person to whom the student can come with questions to answer or disagreements to settle, and that should be the primary point of contact between common people and the educational system, through whom teachers and researchers are brought into the equation. In addition to private teachers, the "executive" role also has need for public educators, to speak up against widespread public falsehoods, and prevent the growth of "cults" of kooks, cranks, and quacks, in the absence of any epistemic authority, so that such groups do not grow and in time become epistemic authorities, i.e. full-blown religions, who would then undermine the very epistemic freedom that enabled their growth (in the same way that gangs and warlords spring out of the power vacuum in an insufficiently governed society, and then grow into new states). -

Stoicism: banal, false, or not philosophy.Broadly on the topic of this thread, I'd just like to note that philosophical counseling is a thing.

-

How much philosophical education do you have?I notice that we now have at least one student, a couple more people who say they have no philosophical education at all, and someone who took some pre-college classes. Welcome all!

I'm curious, whoever it is that took some pre-college classes, what they were like. I had a philosophy class in high school and I don't feel like I came away from it with an understanding of what philosophy was at all, but that could have been because I was a dense scientism-ist at the time.

(We really need a word for a proponent of scientism, because "scientist" obviously isn't it). -

What’s your philosophy?Thank you both.

Meanwhile ...

The Subjects of Reality

What is the nature of the mind, inasmuch as that means the capacity for believing and making such judgements about what to believe? — Pfhorrest

There are two things to consider about what people call "mind":

One of them is phenomenal consciousness, the topic of the so-called "hard problem of consciousness". This is basically just the having of a first-person experience at all. I consider that to be a triviality: I reject both eliminativism which says that there is no such thing at all, and strong emergentism which says that certain arrangements of things that have nothing like that at all can suddenly come to possess that in full, in favor of the view that everything has some degree of such phenomenal consciousness, varying according to the function of the thing.

The other is access consciousness, the topic of the so-called "easy problem of consciousness", which is about the functional ability of a mind to access information about itself; it is, basically, self-awareness. I hold that this is uncontroversially a functional property, held by anything that implements the proper reflexive function, whatever its substrate. I sketch out the necessary features of such a function as such: the system must first differentiate aspects of its experience into their relevance either for a model of the world as it is (a model made to fit the world), which I call sensations, and for a model of the world as it ought to be (a model made for the world to fit), which I call appetites; a function that I call sentience. It must then interpret those experiences into such models, forming what I call feelings, divided into perceptions on the one hand, and desires on the other hand; a function that I call intelligence. It must then reflexively form both perceptions and desires about those feelings, which reflexive states I call thoughts, divided into beliefs and intentions; a function that I call sapience. The descriptive (mind-to-fit-world) side of that sapience function is what I deem rightly deserves to be called "consciousness", as in access consciousness. (The prescriptive side of it will be the subject of my later answer about the will). -

The Time in BetweenIs it not equally impossible for every two points on a line to have distance between them, because it would result in infinite distance between any two points?

Yes, it is equally impossible, which is to say it's not impossible, because that doesn't happen. Any two points on a line have distance between them, because if they didn't they would just be the same point. But those distances can get arbitrarily small, so you can add a point any two points on a line and still have only finite distance between all of the points, then add more points in between those and still have only finite distance between them all, because the distances in question just get smaller and smaller the more you do that. There are infinitely many points on the real number line between 0 and 1, but not an infinite distance between 0 and 1. The same applies to points in time as to points in space.

That's assuming an abstract idealized continuous space and time, of course. Real space and time are probably quantized, as Seagull says, though the details of that are still up in the air awaiting a theory of quantum gravity. -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...From your description in that other thread, that is exactly the same thing that I am talking about under the more traditional name of panpsychism. It says nothing at all about the "emergence" of things with "cognitive descriptions [...] appropriate for the internal/introspective perspective" (phenomenal consciousness) from things without one, which is the meaning of "emergence" used in philosophy of mind, in the sense that distinguishes it from panpsychism.

(@180 Proof I was typing this paragraph as you replied and it appropriately addresses your response as well). There is absolutely no contention whatsoever that the function of cognition, the likes of which even a philosophical zombie is supposed to have, can emerge from aggregates of other, simpler functions. That is not the thing that is at question here, there is no doubt about it, and that's why it's called the "easy problem".

What is at question in the "hard problem", to use Pantagruel's terms again, is whether nothing has an "internal perspective" (eliminativism), whether some things have no "internal perspective" but if you combine those things right suddenly something does have an "internal perspective" (emergentism), or whether everything has an "internal perspective", that varies along with the function of the thing (panpsychism). I hold to the last position.

On a panpsychist account the specific kind of internal perspective that humans have "emerges" along with our evolving functionality just like the "external perspective" of our behavior does (because the experience and the behavior are just two sides of the same functional coin), but the mere having of an "internal perspective" at all is something that was always there at the fundamental level, and didn't suddenly pop into existence when things with no "internal perspective" were combined just right. @180 Proof you seemed to be applauding this when I said it earlier; to quote myself where you bolded me: "The mere having of a first-person experience isn't some special phenomenon that occurs only in humans and so needs an explanation, it's just a basic feature of existence."

From your wikilink to Emergence, look at the section on Strong and weak emergence, especially the Viability of strong emergence subsection, which includes a quote saying of strong emergence that "it is uncomfortably like magic". There is no contention at all over weak emergence of functional properties like access consciousness; that is, again, why that is the "easy problem". It's the strong emergence of phenomenal consciousness that is a contentious position regarding the "hard problem". -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...Systems philosophy, from what I can tell, appears to be speaking only of access consciousness, the subject of the so-called "easy" problem of consciousness. There is no question in philosophy of mind about the possibility of that to be emergent in that sense. We're talking about the hard problem of consciousness, and thus, phenomenal consciousness. Claiming that phenomenal consciousness emerges from wholly un-phenomenally-conscious parts is a completely different thing.

Temperature, for example, emerges from simpler mechanical motion, in a way that makes perfect sense. We can explain what it is about the simple mechanical motion of the constituent particles of a macroscopic object that we are considering in aggregate when we talk about the property of "temperature". Temperature is in that sense reducible to mechanical motion. My body has a temperature. Each my my organs has a temperature. So do each of their cells. And their organelles. At some point we get to talking about individual molecules and then it doesn't make so much sense to talk about temperature, but we can still talk about the kinetic energy of those molecules, which is what temperature is an aggregate measurement of. And then we can talk about energy more generally when we get down past the level of molecules, and so on. There's something that has precursors to "temperature" all the way down, such that if you modeled just those precursors in a simulation, you would end up modeling temperature for free along the way, just in way finer detail that you need to if temperature is all you're concerned with.

Phenomenal consciousness, on the other hand -- the topic of the hard problem of consciousness, the subject of this thread -- is by definition something independent of properties like that. Phenomenal consciousness is what a philosophical zombie is supposed to lack that a real human has, where a philosophical zombie is by definition identical to the real human in every physical way. One could say that there is no such thing as that, that nothing has it, not even humans, and so dismiss the problem completely, but that's not to give an answer to the "hard problem of consciousness", it's just to dismiss it as a non-problem. If one wants to say instead that real humans do have phenomenal consciousness, but that something like a rock doesn't, then you're going to have to explain where along the way this property that is defined to be something wholly irreducible to the properties that humans and rocks have in common "emerged", and how. If you disassemble a bunch of rocks and then reassemble their atoms into cells and assemble those into tissues and assemble those into a human body, where along the way did this new phenomenal consciousness property spring into existence, and from what? There's no doubt that you can in principle show where the access consciousness sprung into being, because that's just a more-or-less mechanical function of neurons (though actually showing the details of that in practice is a much harder problem, but a problem for neuroscientists, not philosophers). But when and where and why did this wholly new thing start happening? That's the spooky magic (@180 Proof) that emergentism about phenomenal consciousness claims happens.

The third alternative, besides nothing having phenomenal consciousness or anything like it, and it suddenly springing into existence out of whole cloth from things that had nothing like it, is that everything has something like it, which is what panpsychism is. A real human brain has it. A chimp brain has a different kind of it. A rat brain has an even more different kind of it. A slime mold has something even more different, and a tree likewise. Even rocks, and electrons, and quantum fields, have precursors of it. This is almost tantamount to dismissing the problem just like eliminativism does, except rather than denying that anything has this first-person phenomenal experience, it just says that everything has that and there's nothing remarkable about merely that -- it's the first-person phenomenal experiences of being the complex access-conscious things that we are that is remarkable. And that complex functionality is describable in ordinary mechanical terms, and can emerge from simpler mechanical systems uncontroversially. But that's not the "hard problem of consciousness" we're talking about any more, that's the "easy" problem instead. -

Stoicism: banal, false, or not philosophy.

It complicates it because, as someone else said after me, someone might want to eradicate grief but not eradicate memory. I know I would. Eradicating the grief doesn't mean changing your preferences about the situation, like thinking that your partner dying is just as good as her not dying. It just means not feeling the actual pain of it.It doesn't complicate it, it just renders vivid the point - which is that sometimes we ought to hurt. If the pill eradiated grief, it would be wrong to take it after your partner has just died. Wrong, because you ought to grieve. — Bartricks

For example, for most of this year I have suffered with a horrible anxiety about death -- my own, that of my loved ones, of strangers around the world, of poor wild animals being eaten by other animals, of the world, of the whole universe in trillions of years. Nobody particularly close to me is particularly close to death in a way that most people would think would warrant this kind of crippling panic about it, so when I say to people that I wish I would stop feeling this way, everyone understands. Nobody thinks that I wish that I was indifferent about any of that. When I'm not suffering from that panic and anxiety, I still prefer to live as long as possible, and for everyone else to too. I'm just not crushed under emotional pain about the seeming inevitability of it; or I'm wishing I wasn't, when I am.

Right now as I typed this sentence, countless other people I've never met died. Right now, I'm not feeling cripplingly awful about that, but I still think it preferable that they hadn't. That's a reasonable thing, no? It's better that I'm not crushed under the emotional weight of all these deaths happening right now that I can't do anything about, isn't it? What is different about the case of a single loved one's death? Obviously, there are factual differences about how easy it would be to shrug off that pain, and so it's far more understandable that someone would be hurt by that more than by the death of millions of strangers they never saw. But that's like saying it's more understandable that someone would be hospitalized by a gunshot wound than by a stubbed toe; most people are tough enough to take a stubbed toe, but not a gunshot would. What we're talking about is the emotional equivalent of being bulletproof, and whether or not you ought to be. Nobody is saying that it is somehow wrong of someone to fail to be bulletproof, or "emotionally bulletproof", but if you can somehow manage to be, why ought you not?

That's what a reason is. You keep typing "Reason" with a capital R, and referring to it with personal pronouns, like you think it's some kind of deity. A reason is just a justification, a motive, a "because" given in answer to a "why" question. I ask why is it unhealthy to be able (if you are able) to shrug off emotional pain more easily or quickly. If you say "because reason", that's like saying "because because". It's not an answer.When you ask for 'a reason' what you actually mean is not a reason, but an explanation that you personally find satisfying. — Bartricks -

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...Emergence in philosophy of mind means something different from that. In this context it means that phenomenal consciousness, something defined as irreducible to any functional properties, emerges in certain arrangements of things that do not themselves have even any precursor to it, as though by magic. Functional properties can emerge from complex arrangements of other things with simpler functional properties, but if some wholly new irreducible thing is supposed to emerge, you’re talking magic. The alternatives are either the “new properties” don’t really exist (eliminativism), or precursors to them already existed in the component pieces (panpsychism).

-

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...Emergence is only one proposed solution to the hard problem. Dualistic accounts address the same problem and have their own share of difficulties. The remaining option is panpsychism, which I advocate above.

-

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...The hard problem of consciousness is hard because it's an illusory problem so there is no solution, only dissolution. The mere having of a first-person experience isn't some special phenomenon that occurs only in humans and so needs an explanation, it's just a basic feature of existence. What's interesting about humans is the particulars of our experience, which correlate with our behavior, both being a product of our function, which is the subject of the "easy" problem of consciousness, which is actually much harder than the so-called "hard" problem; though the hardness is not philosophical but rather scientific.

-

Hard problem of consciousness is hard because...Law of Excluded Middle or commonly referred to law of non-contradiction — 3017amen

Technically those are different things. Non-contradiction says it can’t be both true and false. Excluded middle says it can’t be anything but true or false. The two together are the principle of bivalence. -

Stoicism: banal, false, or not philosophy.Taking a pill to forget that the grief-causing event happened complicates the scenario, because most people would choose not to forget even if they would choose not to hurt.

Consider also that such feelings like grief naturally fade over time, and we consider that to be a kind of emotional healing from an emotional wound. If one were able to heal faster, or less vulnerable to wounds in the first place, why would that be bad? And to say that it would be good is not to fault those who do suffer such wounds and take long to heal; I’m not saying that people who get hurt and take time to recover are doing something wrong. You, in contrast, are saying that those who can heal faster or take more trauma without injury are somehow doing something wrong, and I’m calling for you to back that up instead of just calling it obvious to “Reason”. Reason without a reason is just an assertion of faith.

And if I had a friend who seemed eerily unperturbed by a trauma, my fear would be that he was only hiding his pain that I would expect he dis really feel — but if he convinced me that he had genuinely moved past it already, I would be proud of and happy for him. -

Stoicism: banal, false, or not philosophy.You’ve only asserted that there’s something wrong with not feeling bad in the face of tragedy, when I asked for a reason why that’s wrong. I’m not asserting that it’s irrational or otherwise wrong to feel bad in such circumstances, just that to whatever (dubious) extent someone has a choice in the matter, there’s clearly nothing wrong that I can see about choosing not to feel bad. If you think there is, I’d like to hear a reason.

-

Stoicism: banal, false, or not philosophy.Why ought anyone ever be unhappy, if they can manage not to? What use is it to feel bad, all else being the same?

-

Plantinga's response to Hume's argument regarding the problem of evilPlantinga's ii and iii sum up to "possibly, it is not possible for there to be a world where evil is not possible, and the world we have now is the least evil possible because lacking free will would be way more evil than any evils free will permits".

So Plantinga's really just saying, when it comes down to it, "maybe a world with no evil isn't possible", and so letting God off the hook for that in the same way we'd let him off the hook for not making square circles. But Planty, why might that be the case? Why would free will require allowing other evils, for one thing, but also, why would a world without free will be so much worse? "Maybe they are", you say, but I answer "could they really be, though?"

Plantinga asserts the possibility of there being some excuse for God to allow evil, but I can just as easily assert the impossibility of such an excuse -- as the OP seems to do. Hume's argument is basically "there's no excuse", and Plantinga says "maybe there is", and acts like that "maybe" he baldly asserts is enough to stave off any further "no, there's really not". But no, it's really not. -

What’s your philosophy?Meanwhile I'll continue slowly answering my own questions.

The Methods of Knowledge

How are we to apply those criteria and decide on what to believe, what descriptive claims to agree with? — Pfhorrest

In a word, critically. By which I mean in the manner of critical rationalism, as opposed to justificationism. We should not start off by rejecting all beliefs, and then admitting only those that can be conclusively proven using the empirical criteria given above. We should instead start with whatever beliefs we feel like starting with, believing whatever seems true to each of us -- tentatively agreeing to disagree if different things seem true to different people -- and then, by examining the consistency of our own beliefs with each other, and of our own and others' beliefs with further empirical experiences, start ruling out possibilities, continuing to believe whatever seems true to us within the range of remaining possibilities. In this way we each get less and less wrong, and we come into further and further agreement. But we can never finish that process, never be absolutely certain about what one specific possibility is definitely real, and so never completely eliminate all room for disagreement. Within that range of possibilities, however narrow, we should pick whichever one requires the least information to describe the same set of empirical data, because that is the most useful to us, the easiest-to-use model that still fits within the narrowest range of possibilities we've settled on thus far. -

What’s your philosophy?@StreetlightX or someone, would it be possible to split this conversation with creativesoul off into its own thread? I don't want to shut down that conversation but I still don't see what any of it has to do with the OP of this thread, and never have.

-

The bourgeoisie aren't that bad.This thread wasn’t in the Lounge when I started replying to it, and the only thing bringing me back to it is people replying to me.

-

The bourgeoisie aren't that bad.I don’t know what you’re talking about but can you please point me to an ignore function here because it’s clear that you’re a witless capitalist apologist with nothing worthwhile to contribute to any conversation. I had a bad feeling about your empty Wittgenstein fanboy discussion-stoppers in my other thread, and this just confirms it.

-

The bourgeoisie aren't that bad.You don't seem to understand the point of this conversation. Yes, we're talking about small businesses, which are most businesses. And of course the business itself doesn't borrow from itself. But when the entrepreneur is someone sitting on mountains of cash, they don't have to borrow at all; while when the entrepreneur is an average nobody, they do. The person who doesn't have to borrow has a tremendous advantage. Most of those who start new businesses don't have that advantage, because most people aren't that rich. A tiny fraction of those not-rich business-starters get rich from their successful businesses. A much larger fraction of the tiny number of rich business-starters succeed, because they can afford to fail over and over again until they do. The point is that those who start out with lots of money have an advantage in getting more money faster, even if all other factors are equal, even if they’re equally willing to take risks and equally ingenious and hardworking and good with money. Saying that most people aren’t that amazing is besides the point. The differences between otherwise identical people, who only differ in the money they have to start with, is the point.

And yes, the entire point of that second comment is that poor people spend more of their income, because the cost of living is a greater fraction of that income. So the same money split across more people will end up with more of it being spent. Give me $10,000 and I'll stuff it in my retirement account. Give a bum on the street $10,000 and he'll spend it all staying off the streets for a few months. So more of the $10k gets spent in the bum's hands than in mine. -

What’s your philosophy?Yeah I've told you what I think belief consists of, and what I think thought consists of, and you haven't told me what you think either of them consist of, or what's wrong with my answers, or what any of this has to do with the OP, which was a series of questions and not any statements about anything, so at this point this subthread really just seems like a disruptive derailment to me and I'd rather not continue it.

-

What’s your philosophy?I described thought as reflexive mental activity. If that wasn’t clear then I think you’re not understanding anything I’ve said. I think I would rather just discontinue our conversation, it seems pretty fruitless and proceeding sound frustrating unproductive. If you want to say what you think I’m wrong about and what’s right instead though, go right ahead, cause I'm lost on what you think the problem is.

-

The bourgeoisie aren't that bad.The interest is exactly the problem. You’re looking at the risk from the lender’s point of view, when my whole point is that the availability of credit does not ameliorate the problem that those who already have lots of money can afford to take risks that those who don’t have a lot of money cannot. If two otherwise identical people differ only in that one of them has to borrow from a bank at interest and subject to the bank’s judgement while the other can “borrow from himself”, the latter person has way better odds of coming out ahead in the end. That was already the case without the bank in the picture, and adding the bank to the picture didn’t fix the problem.

-

The bourgeoisie aren't that bad.My earlier point was than most new business ventures fail, so if you can’t afford to fail enough times to hit the jackpot and come out ahead, saying “take risks and it’ll pay off” is bullshit. You suggested credit ameliorates that problem, but it doesn’t change the underlying odds at all, only costs you money whether you win or lose — it’s just a vehicle for those who have the money to gamble until they hit the jackpot to gamble on your livelihood.

-

The bourgeoisie aren't that bad.Better than nothing — Wallows

No actually, quite worse than nothing, as I had just explained. Having access to credit doesn't improve your odds of winning or losing, you're still every bit as likely to fail and just as unlikely to succeed; going into debt to do it it just makes your losses worse and your (still very unlikely) wins worse, to the benefit of those who gambled on you.

Consider the clear-cut case of someone literally gambling at a casino, where the odds are explicitly stacked in favor of the house, so by definition of that you're more likely to lose than to win. Does extending credit (at interest) to the poor schmucks playing there anyway make the situation better for them, or worse? -

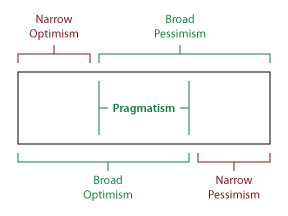

Arguments against pessimism philosophyTo quote myself from the old thread Mark linked to, there's different kinds of "optimism" and "pessimism" that I think it's useful to distinguish between:

"Broad Optimism" in the sense that a solution is possible, the negation of narrow pessimism.

"Narrow Optimism" in the sense that a solution is guaranteed, a subset of broad optimism.

"Broad Pessimism" in the sense that a solution is not guaranteed, the negation of narrow optimism.

"Narrow Pessimism in the sense that a solution is impossible, a subset of broad pessimism.

These are just the four basic logical modalities (possibility, necessity, contingency, and impossibility) applied to the solvability of the problem.

My earlier comment was targeted against narrow pessimism, and is equally applicable to narrow optimism. Taking success to be either guaranteed or impossible is an excuse to not try; there's no point in trying unless success is merely possible, possible but contingent, and there's no possibility of success without trying, so assuming success is merely possible is necessary for success to be possible at all. -

What’s your philosophy?The Objects of Reality

What are the criteria by which to judge descriptive claims, or what is it that makes something real? — Pfhorrest

Commonality to all empirical experiences, or instrumentality toward explaining such. This means an empirical realism, or a physicalist phenomenalism, a kind of neutral monism, where all that exists are physical things, and physical things consist entirely of their phenomenal, experiential, empirical properties, which are in turn just the way that they interact with observers (who are in turn just other physical systems).

This means that the most concretely real of things are only the presently occurring "occasions of experience" (as Whitehead calls them), such as the "pixels" (so to speak) of whatever you're seeing at the moment. Concepts of quantity and quality ("universals" like shape and color) are abstractions useful for explaining patterns in those experiences, so things like shapes in your field of vision are abstractions away from those "pixels of vision", and real inasmuch as they're instrumental in explaining that. Things like rocks and trees existing in three-dimensional space even when you're not looking at them are further abstractions and real inasmuch as they're instrumental in explaining that.

In a sense "here" is more concretely real than "there" (we only infer the existence of "there" from things going on here; even if you can see "there" right now, it's via photons that are here now that you do so), but "there" is still real. Likewise time: the present is more concretely real than the past or the future (we only have records of the past and predictions of the future, all existing in the present), but the past and the future are still real. Likewise other possible worlds: the actual world is more concretely real than other possible worlds, but other possible worlds are still real. I actually hold that time is definable in terms of possible worlds, and space is definable in terms of time, so possible worlds are a more primitive abstraction than time or space.

Purely abstract objects like discussed in math are the least concrete things of all, finally leaving all concreteness behind, but are still real inasmuch as they're useful in explaining the concrete world, as merely one of those infinitely many abstract objects, the one of which we are a part. -

What’s your philosophy?Why do you claim reflexive mental activity requires naming or other linguistic capability?

More to the point, where are you going with all this? I don’t mind so much explaining what my philosophy is like ahead of schedule but this all started with you objecting to the questions in the OP, and now you’re more or less asking me those same questions, so I don’t see your point in doing so.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum