-

What It Is Like To Experience XThat is a contingent empirical question for psychologists/neuroscientists and computer programmers to answer, not a philosophical question.

-

What It Is Like To Experience XThe functionality doesn't explain the subjectiveness of the experience; everything just has subjective experience, but what that subjective experience is like varies with the thing's functionality, just like it's behavior varies with it; the function maps experience to behavior. That's why I'm saying the subjectiveness part of it, the phenomenal consciousness, is trivial: everything has it, it doesn't distinguish between anything. What distinguishes between things is their functionality, and thus both their behavior, and what their subjective phenomenal experience is like.

-

What It Is Like To Experience XIt's not a trivialism when we try to determine whether machines can be conscious, which is also the case for other animals. Does a pig or a cow experience pain, and if so, is it ethical to eat them? Should we medically test rats if they have subjective experiences of suffering?

Those are meaningful questions. — Marchesk

Yes, but the existence of phenomenal consciousness is a trivialism within the worldview (that I have) that of course pigs and cows and rats experience pain and of course machines can be conscious, if they have the right functionality to do so (which pigs and cows and rats and humans clearly do), because to deny that something with all the functionality a human has to experience (e.g.) pain is in some way not really experiencing it is just nonsense on such a view. The existence of phenomenal consciousness meaningfully distinguishes such a nonsense view from mine, sure, but it's not something that's special about humans, not something that distinguishes us from anything else. The functional stuff about access consciousness totally is, though. -

Rigged Economy or Statistical Inevitability?I’ve never heard that definition of socialism. — NOS4A2

Socialism in its broadest sense means any system where there is not an economic class divide between those who own and those who work; where everyone owns some of the means of production and everyone works them too. That division into owners and workers is the definition of capitalism; "free market" is not sufficient to count as capitalism, and there can be non-capitalist free markets, and non-free-market capitalism. It was actually Marx who first argued that free markets inevitably lead to capitalism, much to the disagreement of the other socialists of his time, the ones now called libertarian socialists in contrast. Libertarian socialists are the continuation of the original liberal movement toward both liberty and equality; those liberals who did not abandon equality for capitalism became the first socialists, and those socialists who did not abandon liberty for statism after Marx and then Lenin et al are the libertarian socialists.

That division into non-working owners and non-owning workers is the consequence of the problem described in the OP, and described by older socialist thinkers. Anyone who wants to avoid that division into owners and workers is some kind of socialist, whether they realize it or not.

I was speaking in terms of comparison, not absolute. — NOS4A2

In terms of comparison, a growing inequality definitionally makes more people poor, even if their absolute material conditions don't change or even improve, so "in terms of comparison" your argument is even weaker.

Not in places that were already developed capitalist countries then and still are now, like America. I gave you a couple of big examples in my last post to the contrary, so you can't just assert "nuh uh" in response. Show me how fewer Americans are poor today than 50 years ago, in terms of real basic necessities like housing and medicine, not luxury technological advancements like phones and computers.Yes, people are more wealthy today—financially, health-wise and in living standards—than they were 50 years ago. — NOS4A2

Not only that, but countries that only recently instituted free market policies are much wealthier now than they were only 20 years ago (China for example) — NOS4A2

That's because those countries are also developing countries, technologically-speaking. Of course a country moving out of an agrarian period into an industrial period is going to get richer. That's not a consequence of their economic system, that's a coincidence.

Also, countries getting richer does not mean their poor are getting better off. Saudi Arabia is a fairly rich country, but almost all that wealth belongs to the royal family. Oil sales don't benefit the Arabian plebs much. -

Rigged Economy or Statistical Inevitability?It’s the socialism part I’m opposed to. We shouldn’t ignore its dismal and in fact deadly track-record. — NOS4A2

You seem to think "socialism" implies statism; I'm guessing you're thinking of the USSR. "Socialism" just means any system that avoids the consequences described in OP, of runaway wealth concentration. Libertarian socialism aims to do that without using the state; libertarian socialists are generally anarchists, and anarchists are generally libertarian socialists. Have you ever read anything at all about libertarian socialism?

I was speaking of the poor, not an average person. How was it better to be poor in the 50’s than today? Did they have a better quality of life? A higher lifespan? — NOS4A2

You wanted to define poverty in absolute terms earlier, yet here you seem to want to define it in relative terms. My point was that average people are much poorer today than they used to be; more people are poorer in absolute terms.

In absolute terms, I am poor; even if I could somehow magically consume nothing whatsoever, I am trapped in a situation, that I was born into, of owing someone or another money just for the right to exist somewhere without breaking the law, and am only very slowly making progress on the very long uphill climb to escape that situation. But in relative terms, I am ridiculously wealthy; I have a much higher income than the vast majority of individuals in this country (half of whom make half or less of what I do) and consequently a much larger safety net (compared to most people who have zero safety net) because I am actually making some progress toward climbing out of this hole (compared to most people who are making zero if not negative progress).

Fifty years ago, only people who were relatively poor -- poorer than average -- would face this kind of absolute poverty, and relatively average people would be better-off in absolute terms than even I am. Now, because of runaway wealth inequality, even people who are relatively wealthy, like me, are poor in absolute terms.

Housing is just my go-to example, BTW. Health care is another good one. Flat screen TVs and avocado toast are non-sequiturs, so don't even go there. -

Rigged Economy or Statistical Inevitability?I am, in fact. What I disagree with are the statist prescriptions. — NOS4A2

Then you should be down with libertarian socialism, which is anti-state (hence libertarian) but still looks for other ways to solve the problems of capitalism rather than just ignoring them.

In which period, then, is the poor wealthier than they are today? — NOS4A2

You just named one: 50 years ago. An average person my age in America 50 years ago would be well on their way to homeownership and eventually getting out from under the thumb of their landlord/bank, whereas I’m way ahead of most of my peers and lucky to own a tiny mobile home on rented land. -

Why is so much rambling theological verbiage given space on 'The Philosophy Forum' ?I'd need to study philosophy for at least 40 years before the term "continental philosophy" would start to gain any meaning. — god must be atheist

Here's an attempt to condense a 40 year education into one paragraph for you, then:

In the early 20th century, philosophy in the English-speaking world became dominated by a group of philosophers who put very heavy emphasis on logic and empiricism, focusing almost all their philosophy on language and mathematics and leaving everything else either to be the work of the natural sciences or else denounced as utter nonsense. They emphasized philosophy as a professional academic discipline concerned with rigorous logical analysis of concepts. Like-minded philosophers from across continental Europe fled to Britain and America during the build up to WWII. Their way of thinking and its descendants are the Analytic branch of contemporary philosophy that still dominates in the English-speaking world of professional philosophy today (though not so much in other humanities departments). In contrast, all the rest of contemporary philosophy is "Continental", referring to the continent of Europe in juxtaposition to the islands of Britain, and by comparison to the Analytic tradition it focuses more on philosophy as an examination of the lived experience of being a person embodied in the world trying to figure out what to do and why.

All of this is speaking only of the Western philosophical tradition, and doesn't really apply to Eastern or other philosophical traditions at all. -

Rigged Economy or Statistical Inevitability?50 years ago is a bad choice of time period. Compare the difficulty in securing basic necessities like housing in 1969 vs 2019. There’s lots of cheap technological luxuries available today that didn’t even exist then, but just making ends meet is much harder than it used to be.

-

Rigged Economy or Statistical Inevitability?If you admit that poverty is a problem, and you concede the conclusion of this "new" research that unregulated "free" markets result in the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer, then it seems like you must then admit the latter effect is also a problem, because the poor getting poorer results in ever-increasing poverty, which you admit is a problem.

-

What's with the turnover rate?riding a white horse I think though I don't know why — Ciceronianus the White

Because white horses are the master race of horses, of course. -

Rigged Economy or Statistical Inevitability?That sounds like you're just choosing to ignore the problem then, if you admit that unregulated "free" markets inevitably cause runaway inequality, but you're against both regulation and fixing the structural problems of the market.

-

Rigged Economy or Statistical Inevitability?So you support some kind of libertarian socialism then?

-

Rigged Economy or Statistical Inevitability?As far as the same principles applying to physics, keep always in mind that human societies are just another physical system subject to the laws of thermodynamics, and that wealth is basically just an evaluative perspective on the same old matter and energy, so flows of wealth will be bound to the same rules as flows of energy in the end.

-

How much philosophical education do you have?I’m curious who the one person currently studying it in college is.

-

Supernatural magicEverything supernatural has this same flaw, not just “supernagic”. The supernatural by definition has no observable impact on the observable universe.

-

Rigged Economy or Statistical Inevitability?It assumes that economic inequities are the result of intentional exploitation of the masses by an evil minority. — Gnomon

Not at all, it posits that ongoing inequities are a result of systemic features of the political-economic system that reward and punish the respective sides of preexisting inequities. Everyone is just doing their best to get ahead, but the system rewards those who are already ahead allowing them to get even further ahead, and punishes those who are already behind making them fall even further behind. It’s not about mustache twirling evil villains, it’s about systemic injustice.

It’s like you’ve never even heard a Marxist critique before. E.g. the big banker villain of Mary Poppins Returns was widely criticized from the left as making it seem like it’s just a few bad actors like that behind all the problems and if they’re just defeated the system will work fine again, when really it’s the system that’s at fault and the individuals in charge of it are largely irrelevant.

Basically this “new” research is just reinforcing what Marxists have always been saying.

FWIW I agree with the conclusion that “free markets” as we have them today inevitably lead to inequality, but disagree that state intervention is the only solution. The problem is in the nature of the rules of allowable transactions in the “free” market, which still has all kinds of claim rights (e.g. to property) and powers (e.g. to contract), not just a complete free reign of unchecked liberty rights. Libertarian socialism and left libertarianism are views that address those underlying rules to fix the problem without state intervention, usually by limiting the claim right to property, but on my version by limiting the power to contract (especially contracts of rent and interest), in any case actually increasing the freedom of the market, not decreasing it, while undermining the systemic advantages that such claims or powers give to those who are already ahead in the game. -

Material alternative to theismThe physical world may be reducible to mental stuff inasmuch as physical means empirical means experiential or phenomenal, but minds in turn are instantiated in the functionality of physical things. The physical is mental and the mental is physical because there is no clear division between the two, just two literal perspectives (first and third person) on the same one kind of stuff: information encoded in energy.

-

How important is (a)theism to your philosophy?That is an interesting point of view because it seems to derive an “is” from an “ought”: there ought not be any ruler, therefore there is no god. Do I take it that you mean not so much to say that any particular thing or other does or doesn’t exist, per se, as to say that whatever it is that may or may not exist, none of those things deserves the title of “god” and fhe normative implications of a right to rule that would come with that?

-

Constitutional Interpretation: USA Article I, Section 3Sorry, just replying to Terrapin.

I voted Yes BTW. -

Constitutional Interpretation: USA Article I, Section 3Democrats don’t need someone “moderate” i.e. Republican Lite, they need someone who supports things the left half of the electorate actually want instead of just being the lesser evil.

-

Should you hold everyone to the same standards?You should hold everyone to the same standards, but the formulation of those standards should include variables for variable circumstances etc. Treat all like people in all like circumstances alike.

-

An Argument for Hedonismunpleasantness is a felt property of badness — TheHedoMinimalist

I'd argue for hedonism in a much more direct way from basically exactly that statement.

If we start from a place where we have no idea what's "really" good or bad, or if anything at all even is "really" good or bad, we can at least ask ourselves "what seems good or bad?" That seeming-good-or-bad just is hedonic experience, pleasure or enjoyment, suffering or pain. I like to call the faculties that produce such experiences "appetites", the normative analogue of the senses, which likewise are the faculties that produce experiences of what seems true or false. The satisfaction of an appetite is pleasure or enjoyment, the dissatisfaction of it is pain or suffering.

Just as what initially seems true to our limited empirical experience may later seem false upon further experience, but we still build our picture of what's actually true out of increasingly in-depth examination of our empirical from many different perspectives and in many different circumstances...

...likewise what initially seems good to our limited hedonic experience may later seem bad upon further experience, but since that seeming-good-or-bad is all we have to go on, we should build our picture of what's actually good out of increasingly in-depth examination of our hedonic experience, from many different perspectives and in many different circumstances. -

On beginning a discussion in philosophy of religionSetting aside God as a nonliteral, metaphorical, mythical character as Wayfarer describes above, and focusing instead on the logos interpretation, I was thinking this could be a useful way of helping frame the "what is God" question:

Picture the world you think atheists believe exists.

Now picture the world you think theists believe exists.

Now describe the difference between those two pictures.

That difference is what you think "God" means.

For me, I think that difference is generally the existence of a person of some sort -- some being with a mind and will -- that excels to perfection at all the things that are virtues of a person, having complete knowledge of everything in the universe (omniscience), perfect function of mind and will within itself (including omnibenevolence), and complete power over everything in the universe (omnipotence).

And I don't think such a thing exists.

Other nominal theists seem to think that "God" means either something that atheists wouldn't dispute the existence of, just the labeling of (so there is no difference in the two pictures above), or something poetic, literary, or metaphorical, like "love" or other theologically noncognitivist referents. But for theists who do posit a difference in the world they think exists and the world that atheists think exists, it seems to be something like the above. -

On beginning a discussion in philosophy of religionThe point here being that believing in something and claiming it to independently exist are two different things. Confusion on this point abounds, and people who are confused can be in this respect toxic. — tim wood

This seems to be a confused use of the word "believes". I believe that the sun exists, and that its existence is independent of anything anyone thinks about it. My understanding of most Christians, and most theists generally, is that they have the same opinion about God as I (and probably they too) have about the sun, in that respect.

There might be a difference in their opinion between God and the sun in the respect that they can easily demonstrate the existence of the sun to other people and demonstrating the existence of God might not be that easy. But there are plenty of other mundane things that it is difficult to demonstrate the existence of (faraway celestial objects, tiny subatomic particles) that nevertheless can be shown to exist with indirect evidence and reasoning from that evidence, and plenty of theists seem to think that the existence of God can be indirectly demonstrated in the same way (just look at all the many arguments for why God must exist).

As an atheist I of course think all of those attempts to demonstrate the existence of God fail, but theists obviously disagree.

God is the creator. I think we could get consensus on that. — MU

Ok. Anyone second this? — tim wood

I already raised problems with that in my previous post. -

On beginning a discussion in philosophy of religionWhat's yours on religion? — tim wood

A system of beliefs grounded in faith, which in turn is uncritical belief, belief not to be questioned.

Further, Theists, many, absolutely believe, and as seems best to them profess that belief. With them I at least have no issue. I have my beliefs too, and I think believing is an important aspect of moral thinking. But I know of no even remotely Christian-based thinker who understands his religion (i.e., Christian) who claims g/G has real independent existence. Kant's denial of knowledge to make room for faith is also significant here. But to those who insist their belief is knowledge of, then make it knowledge: show us! Or — tim wood

To believe something is to think that it is true. Christians generally think that God exists, in an objective way, independent of humans thinking that he exists; that he existed before there were any humans to think that he existed. They may not claim to know with certainty or be able to demonstrate that to other people, but they still think that God exists independent of human opinion, and would disagree vehemently (see this thread) that he's "just an idea".

More on the topic of the OP, I thought what you were looking for was consensus on what the idea of God is of, regardless of whether or not that exists. Like, we can probably come to a consensus agreement on what "unicorn" means, and then debate whether or not there are any such things. I thought that's what you were looking for.

God is the creator. I think we could get consensus on that. — Metaphysician Undercover

Nope, even if we're talking about my paragraph above, just agreeing on what it is we're to debate the existence of. The creator of what, and does absolutely anything count as that, whatever it should turn out to have created whatever you mean? E.g. if the creator of the Earth, then does the Sun's protoplanetary disc count as "God"? Or maybe whatever old dead star whose remains that protoplanetary disc (and the Sun itself) coalesced out of? If the creator of the universe, would "quantum fluctuations in eternally expanding space-time" count as God? If "whatever created..." something is all you mean by God, then you're going to end up concluding that there necessarily is a God, because nothing comes from nothing, and even atheists won't disagree that that thing (that whatever came from) exists, they'll just disagree that it deserved the label "God". -

The Problem of Evil and It's Personal ImplicationsFree will theodicies depend on an incompatibilist conception of free will. On a compatibilist conception there is no reason God could not have determined the universe to be all good and also allowed for free will; in fact on some compatibilist conceptions like Susan Wolff’s or my own, free will is identical with responsiveness to moral reasoning, so making people free of will makes them more moral and the world a better place, not worse.

-

On beginning a discussion in philosophy of religionAnybody left out? Anybody have any substantive disagreement? — tim wood

Yeah, I strongly doubt you will find agreement on that of God there from theists, and I personally disagree with that definition of religion.

That definition of theology seems pretty uncontroversial though. -

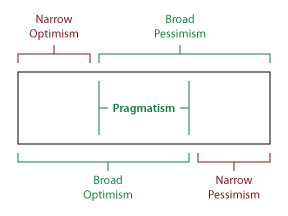

How should we react to climate change, with Pessimism or Optimism?I drew a little diagram of the broad/narrow optimism/pessimism thing for my book last night:

-

Free will seems to imply that this is not the only worldIf we have free will, then the ToE is not able to calculate what we will be doing. — alcontali

You are assuming an incompatibilist conception of free will. On a compatibilist conception, free will has no implications on determinism of lack thereof.

If free will exists, then alternative worlds (that we may call heaven and hell), also necessarily exist. — alcontali

Proving the existence of multiple worlds is far removed from proving the existence of anything we might want to call heaven and hell. Lots of people are modal realists without believing the other possible worlds besides the actual world are in any way religiously significant. -

Would there be a God-like "sensation" in the absence of God or religion? How is this to be explainedFor much of my life I found this search for "meaning" in this sense incomprehensible. I understood the quests for truth, and for goodness, for knowledge and justice, and for means of pursuing those ends. But even in the kind of empirical, hedonic, rationalist worldview that I have long since held — which many writers on the Absurd find to be the prompt for their feelings of meaninglessness (in contrast to transcendent, fideistic, religious worldviews) — I saw the obvious potential for answering those kinds of questions about reality and morality, and couldn't comprehend what more besides that anybody wanted. "Meaning", in this sense, was, to me, meaningless.

Meanwhile however, throughout my life, I had experienced now and then times of intense positive emotion, feelings of inspiration, of enlightenment and empowerment, of a kind of oneness and connection to the universe, where it seemed to me that the whole world was eminently reasonable, that it was all so perfectly understandable even with its yet-unanswered questions and it was all beautiful and acceptable even with its many flaws. I greatly enjoyed these states of mind, and I did find that they were also practically useful both in motivating me to get things done, even just mundane chores and tasks, and also in filling me with creative thoughts, novel ideas and new solutions to problems. But although I eventually learned that these were the kinds of mental states often called "mystical" or "religious" experiences, I never took them to be in any way magical or mysterious. I saw them as just a kind of emotional high, with both experiential and behavioral benefits. Friends who had experience with drugs like LSD would even describe my recounting of such experiences as sounding like a "really good trip", further enforcing my view that these were just biochemical states of my brain (even while some of those friends conversely took their own LSD trips and such to be of genuinely mystical significance). While in such states, some things would sometimes seem "meaningful", in the sense of "important", even when I could see no rational reason why, and I always just dismissed this as a pleasantly bizarre mental artifact of the emotional high I was on. It never occurred to me to connect that sense of abstract emotional "meaning" with the thing that writers on the Absurd were seeking.

It wasn't until decades into my adult life that I first experienced clearly identifiable existential angst like had prompted the many writers on the Absurd for so long. I had long suffered with depression and anxiety, but always fixated on mundane problems in my life (though in retrospect I wonder if it wasn't those problems prompting the feelings but rather the feelings finding those problems to dwell on), and I had already philosophized a way to tackle such mundane problems despite that emotional overwhelm, which will be detailed by the end of this essay. But after many years of working extremely hard to get my life to a point where such practical problems weren't constantly besieging me, I found myself suddenly beset with what at first I thought was a physical illness, noticing first problems with my digestion, side-effects from that on my sinuses, then numbness in my face and limbs, lightheadedness, cold sweats, rapid heartbeat and breathing, and eventually total sleeplessness. Thinking I was dying of something, I saw a doctor, who told me that those are all symptoms of anxiety, nothing more. But it was an anxiety unlike any I had ever suffered before, and I had nothing going on in my life to feel anxious about now. Because of that, at first I dismissed the anxiety diagnosis and tried to physically alleviate my symptoms various ways, but as it wore on for many months, I found things to feel anxious about, facts about the universe I had already known for decades (many of which I detail later in this essay) but never emotionally worried about, which I found suddenly filling me with an existential horror or dread, a sense that any sentient being ever existing at all was like condemning it to being born already in freefall into a great cosmic meat grinder, and that reality could not possibly have been any different. Mortified, I searched in desperation for some kind of philosophical solution to that problem, something to think about that would make me stop feeling that, even trying unsuccessfully to abandon my philosophical principles and turn to religion just for the emotional relief, growing much more sympathetic to the many people who turn to religions for such relief, even as I continued to see the claims thereof as false and many of their practices as bad.

As a year of that wore on, brief moments of respite from that existential angst, dread, or horror grew mercifully longer and more frequent, often being prompted by a smaller more practical problem in my life springing up and then being resolved, distracting me from these intractable cosmic problems, at least for a time. In those moments of respite, I would often feel like I had figured out a philosophical solution to the problem: I saw my patterns of thinking while experiencing that dread as having been flawed, and the patterns of thinking I now had in this clearer state of mind as more correct. But when the dread returned, I felt like I could not remember what it was that I had thought of to solve the problem, and any attempt to get out of that state of mind simply to not feel like that any more felt like hiding from an important problem that I ought to keep dwelling on until I figured out a solution to it, even though it seemed equally clear that no solution to it was even theoretically possible. It wasn't until nearly a year of this vacillating between normalcy and existential dread had passed that the insight finally stuck me: the existential dread was just the opposite of the kind of "mysterical experiences" I had occasionally had and attached no rational significance too for my entire life. Just as, during those experiences, some things sometimes seemed non-rationally meaningful, just an ordinary experience of some scene of ordinary life with a profound feeling of "this is meaningful" attached to it, so too this feeling of existential dread was just my experience of ordinary life with a non-rational feeling of profound meaninglessness attached to it. The problem that I found myself futilely struggling to solve, I realized, was entirely illusory, and it was not irrational cowardice to hide from the "problem", but rather entirely the rational thing to do to ignore the illusory sense that there was a problem, and do whatever I could to pull my mind out of that crippling state of dread, wherein I had painfully little clarity of thought or motivational energy, and get myself back into a clearer, more productive state of mind.

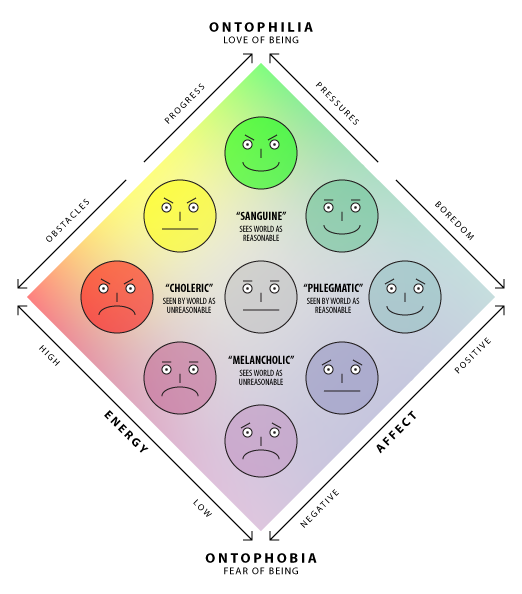

I have since dubbed that feeling of existential angst, dread, or horror "ontophobia", Greek for the fear of being, where "being" here means both the existence of the whole world generally, and of one's own personal existence; and its opposite, that experience of cosmic oneness, understanding, and acceptance, "ontophilia", Greek for the love of being, in the same sense as above. I am now of the opinion that many if not all of the writers on the Absurd, and generally anyone suffering from a feeling of meaningless in life, are not confronting a genuine philosophical problem, but merely an illusory philosophical problem stemming from a very real emotional one. Ontophobia generates the feeling of needing to find meaning in life, not the other way around. Conversely, ontophilia generates a feeling of inherent meaningfulness. Neither feeling is rationally correct or incorrect about any actual philosophical question about meaningfulness, but ontophilia is clearly the better state of mind, both for its intrinsic experiential enjoyability, but also for the practical benefits it confers of enlightening the mind and empowering the will, in the ways discussed in my previous essays on enlightenment and empowerment.

Ontophobia's illusory demand for meaning is essentially a craving for validation, for a sense that one is important and matters in some way. I realize in retrospect that so much of what I thought were mere practical concerns in my life were probably actually manifestations of this ontophobic craving for validation. My youthful longing for romance was all about feeling worthy of a partner; stress about performance at my job was all about feeling worthy as an employee; longing for an appreciative audience for my various private creative works was all about feeling worthy as an author, artist, etc. It was only once those were mostly all satisfied that the bare emotional motive behind them all truly showed itself, the true existential dread being all about craving to feel like it matters whether or not I, or anyone, even live at all.

Ontophilia, on the other hand, can produce equally illusory feelings that nevertheless seem overwhelmingly real and undeniable. Being the quintessential "mystical experience" or "religious experience", it is the supposed source of "revealed" knowledge held to be divinely inspired and infallibly true by many religions. (I am of the opinion that ontophilia is the proper referent of the term "God" as used by theological noncognitivists, who are people that use religious terminology not for describing reality per se, but more for its emotional affect. Most theological noncognitivists do not identify as such and are not aware of this philosophical technicality in their use of language, but it it evident in expressions such as "God is love", whereby "believing in God" does not seem to mean so much a claim about the ontological existence of a particular being, but an expression of good will toward the world and of an expectation that the world generally reciprocates such goodness. It seems also plausibly equatable to the Buddhist concept of "nirvana", or the ancient Greek concept of "eudaimonia", which were the "meanings of life" of those respective traditions). As such, ontophilia still needs to be tempered by more sober reflection; although I have had many seemingly great creative ideas when in such states of mind, not all of them have held up to later scrutiny, though some still have, so not all ideas produced in such states of mind should be dismissed out of hand. Actions motivating by ontophilia can also be manic in their passion and dedication, which if misguided can be dangerous, either to oneself or to others.

I compare ontophilia to mania there deliberately, and likewise I compare ontophobia to depression and of course to anxiety. I consider them to be extremes of one axis of a two-dimensional spectrum of emotions that I devised introspectively to help make sense of my own mental health. I name the four extreme moods of this spectrum after the classical Greek four temperaments, which in turn were named after the four bodily fluids or "humors" that ancient Greek physicians held to be responsible for such temperaments: phlegmatic (after phlegm of course), sanguine (after blood), choleric (after yellow bile), and melancholic (after black bile). I of course don't subscribe to the long-outdated medical theory of these four humors, but the names of the temperaments are useful labels for my purposes here. The model of four temperaments usually casts them as personality types, with an individually being generally more one or the other, but I mean them here as moods, between all of which any one individual may vacillate. I place these four moods in the corners of a two-dimensional axis of emotional energy and emotional affect. Phlegmatic moods are those of low energy and positive affect, a kind of relaxed happiness, what we might call peace. Sanguine moods are those of high energy and positive affect, a kind of excited happiness, what we might call joy. Choleric moods are those of high energy and negative affect, essentially intense anger. And melancholic moods are those of low energy and negative affect, essentially intense sorrow.

I observe in myself that pressure to act increases my energy, while boredom decreases it; and progress in my actions makes my affect more positive, while obstacles make it more negative. I hold that ontophilia is simply an extremely sanguine, high-energy, positive-affect mood, while ontophobia is likewise an extremely melancholic, low-energy, negative affect mood. And just as an ontophilic or generally sanguine mood leads to seeing the world as reasonable, understandable and acceptable, while an ontophobic or generally melancholic mood leads to seeing it as unreasonable, incomprehensible, and terrifying, I likewise observe that other people in the world generally find people in phlegmatic moods to seem reasonable, sane, and safe, while people in choleric moods seem to them unreasonable, crazy, and dangerous. It seems clearly ideal, then, to aim to cycle between ontophilic or at least generally sanguine moods, for the sake of the enlightening and empowering effects they have on the mind and will, and phlegmatic moods for the sake of a more grounded check on how actually true and good the things inspired by the ontophilia are, and to communicate them to others. (This even bears a passing resemblance to the Scholastic philosophers' view of the relation between revelation and reason: they held revelation, which I equate to ontophilic inspiration, to be sufficient to know what was true, with reason there to later investigate further why it was true. I disagree with that on the important point that I don't hold ontophilic inspiration to be infallible, and the role of reason is then to critique the inspired ideas rather than rationalizing justification for them, but I see a resemblance still). Nevertheless, ontophobic or melancholic moods, and even choleric moods, are not entirely without their uses: anger can of course be a useful motivator if properly channelled, and in the depths of the existential dread affecting me I found myself more moved toward compassionate action, both so as not to further contribute to the horrors of reality I perceived all around me, and also as an emotional salve to try to alleviate my own emotional suffering from the same.

On which note, I find that, aside from simply allowing myself to ignore the meaningless craving for meaning that ontophobia brings on, the way to cultivate ontophilia is to practice the very same behaviors that it in turn inspires more of. Doing good things, either for others or just for oneself, and learning or teaching new truths, both seem to generate feelings of empowerment and enlightenment, respectively, and as those ramp up in a positive feedback loop, inspiring further such practices, an ontophilic state of mind can be cultivated. In addition to that practice, I find that it helps to remain at peace and alleviate feelings of anxiety and unworthiness by not only doing all the positive things that I reasonable can do, as above, but also excusing or forgiving myself from blame for not doing things that I reasonably can't do. It is of course very hard to do this sometimes, so it helps also to cultivate a social network of like-minded people who will gently encourage you to do the things you reasonably can, and remind you that it's okay to not do things that you reasonably can't, between the two of which you can hopefully find a restful peace of mind where you feel that you have done all that you can do and nothing more is required of you, allowing you to enjoy simply being. Furthermore, meditative practices are essentially practice at allowing oneself to do nothing and simply be, to help cultivate this state of mind; a popular prayer (that I will revisit again later in these essays) asks for precisely such serenity to accept things one cannot change and courage to change the things one can; and the modern cognitive-behavioral therapy technique called Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is also entirely about committing to doing the things that one can do and accepting the things that one cannot do anything about. — The Codex Quaerendae: On Practical Action and the Meaning of Life

-

On beginning a discussion in philosophy of religionThey can be in error, sure, which is why it's possible that someone could show you good reason not to believe it. But "you don't have good reason to believe it" is not, in itself, good reason not to believe it.

And unless you're a moral nihilist (in which case it's not worth arguing, just stop reading here), it's possible for the things you want to be "in error" too (for you to want the wrong things, things you shouldn't want), so good reasons can also be given to not want those things. But "you don't have a good reason to want that" is not, in itself, good reason not to want it.

They're perfectly analogous. -

On beginning a discussion in philosophy of religionI like vanilla. There's no reopen that I like vanilla, I just do. It's unjustified. SO what? — Banno

I like using this kind of example to illustrate the argument for critical rationalism.

When it comes to why to do (or intend) something, it's pretty much accepted that everyone is free to do what they want just because they want to do it, unless there is some good reason not to do it. Nobody insists that everybody stop doing anything at all until they can justify from the ground up why they should do something, because it's clearly impossible: maybe you want to buy a car so you can get to work so you can earn money so you can buy vanilla ice cream so that you can eat vanilla ice cream so that you can enjoy the taste of it, but at some point you get to something like that where your only justification is that it sounds good to you, you just want it, and "so you have no good reason to do it then" doesn't count as a reason not to do it, at least not to any reasonable person.

But for some reason when it comes to beliefs, too many people are just that unreasonable. Sure you maybe believe P because Q because R because S but you believe S because you just look at the world around you and it just seems to be true, that's just how the world appears, that's just what you believe. Too many people would then say "so you have no good reason to believe it then" as though that's a reason for you not to believe it, but it's not. You're free, epistemically as in you're not committing any error of reasoning, to believe whatever you damn well please, whatever just seems true to you, until someone can show you a good reason not to believe it. -

Is there any problem with quantifying over wff?A variable can stand for a proposition.

"For any proposition P, either P or not-P" is a perfectly cromulent sentence. -

How should we react to climate change, with Pessimism or Optimism?I have had anger problems my whole life, that I've always traced back to echoes of things from my childhood. I've never had anything resembling the anxiety I've felt this year though. I used to think that fear and anger were two sides of the same coin, "fight or flight", and that anxiety was basically a form of fear. About a decade ago, after being in a living situation where I had to be constantly aggressive to protect myself and never show any fear, I developed a weird conflation of fear with anger, such that if I watched a horror movie and there was a jump scare or something, I wouldn't feel anything I'd call fear but rather wanted to smash something. (I think that that has slowly faded over time, I can't remember the last time I reacted like that). I thought I had anxiety for most of the time since then too, having been diagnosed with it, and feeling frequent emotions that I thought were the referent of that term. But starting last winter, I started feeling physical symptoms that my doctor identified as those of anxiety, even though I had nothing to be anxious about and they were unlike any of the feelings I had ever had before. I now think that what I had before was merely stress, and that's why I related it to anger, if what I'm suffering now is actual anxiety, which feels nothing even on the same spectrum as anger.

I think perhaps you meant to send this privately, not post it to this thread? Nothing you've asked is anything I'm afraid to answer publicly, but you said you were sharing personal history you didn't want public. -

How should we react to climate change, with Pessimism or Optimism?If you can act, you do not need to worry, if you can’t act then worrying will get you nowhere.” — Mark Dennis

I agree with that entirely (and just wish I could make my pointlessly anxious brain be okay with it too). There's a lot of different formulations of that in different places, from the famous prayer that asks for "the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can" (and "the wisdom to know the difference", which I normally find the hard part; besides my pointless anxiety this year, I've always found it easy to find the serenity to accept things I know I can't change, and the courage to change the things I know I can, and it's only when I'm not sure which applies to the present situation that I felt uneasy); to the cognitive-behavioral therapy method called Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, which is all about accepting things beyond one's own control and just committing to acting in accordance with one's principles and values.

My difficulty is that just knowing that that's the way I rationally ought to feel doesn't make me actually feel that way. -

Former Theists, how do you avoid nihilism?On a related note, this is a note a wrote to myself last night, that I'll elaborate upon somewhere in the last chapter of my book later:

on the surface of an infinitely deep sea

you cannot fly into the sky, because it is not possible to fly

and you cannot touch the bottom, for there is none

but if you try to touch the bottom, you will sink forever

and if you try to fly, you will at least float

"trying to touch the bottom" in this analogy is trying to justify something (like a reason to live, or a belief, or whatever) from the ground up. There is no ground, so if you try to stand on it instead of just swimming, you'll sink. -

Former Theists, how do you avoid nihilism?Nah you understood right, and I know it's unreasonable, but feeling existential dread in the first place is unreasonable, and just knowing that doesn't make it stop.

-

Why are We Back-Peddling on Racial Color-Blindness?Was the white guy hired because he was white?

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum