-

What are we doing? Is/ought divide.What-is is not subject to infinite regress either; it is simply what appears to us in its concreteness. — Janus

oughts are not subject to infinite regress either, but find their termini in purposes — Janus

I didn't say that both were doomed by infinite regress, just that they were "just as subject to": a regress argument against one would work just as well against the other, and a defense of such argument would defend both. You've just named the respective forms of that defense: we don't have to justify everything out to infinity first, we can work from what we just happen to think is true/good and justify other things relative to those. Just so long as we remain open to revising those things were just so happen to think are true/good, if reason to think otherwise comes along, and don't take our prima facie assumptions to be some kind of indubitable axioms. -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesHarris thinks that we should stop talking about moral philosophy, just take it as an unquestioned working definition that flourishing is good and suffering is bad, and then start a scientific investigation of what causes flourishing and suffering and therefore what is good or bad. You likewise are are (or seem to be) advocating that good and bad ends are just pre-known or assumed and can’t be investigated any further than those assumptions, and the only thing to investigate is what causes those pre-assumed good ends. In this way, both you and he claim that you can get an “ought” from an “is”, because some “is”’s have baked-in “ought”ness by assumption or by definition.

I think that in practice that is an important PART of actually doing good; we definitely need to know HOW to attain the states of affairs that are good. And the general nature of states of affairs that you both assume or define to be good (all people feeling good and not bad, more or less) are ones I agree with.

But I’m advocating that we can philosophically JUSTIFY treating that as the criterion by which to judge states as good or bad, in a meta-ethics; and that we can directly and reproducibly experience the good or badness of particular states according to that criterion in the first person, as an ethical science; to arrive at MORE than a mere definition or assumption about the good ends that we then go investigating ways to cause, but rather a defeasible contingent measurement, via a sound moral-epistemological methodology, of what is actually good. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleHow do we know they have been fooled except by further use of them?

— Pfhorrest

We don't — Tzeentch

Then how do we know that there is any reason to doubt them?

Other things are relevant, such as future outcomes/consequences (I.e. long term health vs. short term gratification). — Pinprick

pleasure (or excessive pleasure perhaps) often leads to pain. So if what is meant by hedonism is to blindly pursue pleasure/avoid pain, then I disagree with that, and would advocate for something like “rational hedonism” where the consequences of pursuing pleasure/avoiding pain are considered prior to acting, and potential unwanted consequences are weighed against potential desirable ones. — Pinprick

That is all within the domain of what I mean. Hedonism can be far-sighted or short-sighted. If the long-term consequences you’re concerned about are still all about whether you will be suffering or enjoying life in the future, then that’s still a focus on feeling good or bad, pleasure or pain, etc; it’s just a smart way to do so, that doesn’t shoot itself in the foot.

Eudomonia in Aristotelian philosophy is linked with virtue and with fulfilling your life's purpose (telos). — Wayfarer

What is virtue but good character, a propensity to do good things, to bring about a good (or at least better) world?

What is purpose but what something is good for, what good comes as a consequence of it?

And what is good about some consequences, about some state of the world, besides everyone feeling good, nobody feeling bad?

Doing good does feel good, sure, and it is perhaps the highest form of good feeling, the best feeling even, but what is the “good” in “doing good” other than helping people to feel good and not bad? -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleYou complained in the OP about having to reference a text, and now you depend on it??? — counterpunch

I wasn’t complaining of having to reference it, but of having to write anything at all. Linking to an encyclopedia article about the subject was just filler text.

In any case, as the person who wrote the questions it’s my place to clarify what I meant by them. If you wouldn’t have used words that way, you do you, but just know that that’s what I was using them for, and don’t take them to mean something else in that context.

Our senses are simply too easy to fool. — Tzeentch

My point is: How do we know they have been fooled except by further use of them? Yes, any one particular experience may not tell you the whole picture, but the whole picture is still the sum of all the experiences: -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesEmpathy and moral objectivism are mutually exclusive. — baker

??????

the crazy train — 180 Proof

I actually object to Harris too, for the exact same reason I’m objecting to you: not maintaining the is-ought divide.

Normative ethics' is, for me, the heart of moral philosophy because judgment & conduct are always already situated in conflicted commons, with 'metaethics' & 'applied ethics' derivative and supplimentary. — 180 Proof

Historically, normative ethics is the heart of moral philosophy, yes, and meta-ethics and applied ethics are derivative. The thesis of this thread though is that letting normative ethics split completely between those two derivative directions is the path to the future.

It’s like how the investigation of reality began with speculative “maybe everything is made of water” kind of thoughts that were neither proper natural science nor proper philosophy as we understand it today, but that kind of speculative metaphysics gave rise eventually to both philosophical methods of figuring out what reality is like rather than just speculating about it, and the thorough and rigorous application of those methods in a practice that is no longer philosophical at all.

I think ethics needs to evolve along that same path.

Pfhorrest, I don't always agree with you, but your posts are very nicely written and clear. — bert1

Thanks! -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleI can feed my child all the sugar it wants, and I am sure they will enjoy it greatly, however I would be slowly poisoning them, regardless of their enjoyment. — Tzeentch

What is bad about being poisoned if not the suffering it causes?

The obvious example is from monotheistic religions: moral is that which is in line with God's commandments. — baker

So like I concluded, the alternative is “because someone said so”.

I keep trying to answer your post from 8 hours ago, but then something happens - like someone was responding right now, and I just couldn't get to it. Now I have things to do out in the world. So please don't take this personally, like some sort of snub. It's not that at all. I'll get back to you. — counterpunch

No worries, I’m never in a rush for a reply, and I have lots of other things sucking up my time too. At your leisure. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleMoral conduct — Tzeentch

What makes conduct moral, if not refraining from hurting people (not inflicting suffering), and helping them (enabling enjoyment)? -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleSometimes, it is moral to speak truth to power, for example — unenlightened

To what end, if not to (set into motion or contribute to some movement to) get said power to behave differently, in such a way that said power hurts less (inflicts less suffering) or helps more (enables more enjoyment)? -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleI don't think it can serve as a useful guide. — Tzeentch

A guide to what? That is, in trying "make things good", what is it that you're trying to do... if not ensure that nobody's suffering and everyone enjoys life? -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesI've made that point already. — 180 Proof

I’m responding to that point you made.

You claim answers to "how"-questions were also subject to infinite regresses which may be true in philosophy but not true in science because "how"-answers (i.e. theoretic explanations) are testable-eliminable. — 180 Proof

Being testable alone doesn’t get you out of infinite regress. What gets you into the infinite regress to begin with is demanding that everything test positive before being admitted as a possibility... but then the evidence you used to support that conclusion needs to be tested first... but the evidence to support that evidence would need to be tested even sooner... etc. A science-like empirical investigation could demand absolute positive proof of anything before accepting it... except then it would never get off the ground. It’s the tentative acceptance of possibilities unless they get falsified that gives science its ability to be productively skeptical (critical) without stalling out the gate from staring down a bottomless pit of epistemological despair.

Likewise, the way out of infinite regress in prescriptive questions is not testability, but liberty. You'd get into an infinite regress if you demanded some good end to justify any action, because you'd then have to demand an end to justify that end, and so on. You avoid that infinite regress by not asking "why must this be so?", but "why not?" instead: just like the critical rationalist epistemology employed by the physical sciences allows uncertain possibilities to be tentatively floated, an ethical methodology can allow people moral permission to do whatever things that might or might not turn out to be the most good thing they could do, so long as there's not anything showing that they are definitely a bad thing to do. I'm not at all advocating a draconian, demanding consequentialism here; an infinite regress argument would be a good argument against that position, and I use such argument myself.

All I'm advocating is that in addition to investigating what is the case, what are the causes of various effects, which the fields of study you named are all doing, we also investigate what should be the case, what are the ends toward which the results of those other studies can be means. But just as we don't have to (and could not, so should not try to) complete the infinite regress of causes of causes of causes of causes of the effects we're investigating, we don't have to (and could not, so should not try to) complete the infinite regress of ends of ends of ends of ends of the means we're investigating. We only need to be able to somehow rule out some of those prescriptive, ends-of-means claims, just like we only need to be able to somehow rule out some of those descriptive, causes-of-effects claims.

And to pull this back to the topic again: within the context of advocating that, the novel thing I'm proposing in this thread is that in such an investigation, there are both a meta-investigation into how to conduct such an investigation, and then the results of the actual investigation itself. The first part is meta-ethics, the second part is applied ethics, and normative ethics doesn't really fit into there anywhere, trying to do both and ending up doing them both badly: some nominally different positions in normative ethics are really more like answers to different meta-ethical questions entirely, and the whole thing that normative ethics is nominally aiming to do is really better construed as just the bottom rung of the stack of applied ethics fields. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleBy my definition, hedonism requires the pursuit of my wants, regardless of anyone, or anything else — counterpunch

That's an unusual definition then, and not the one this thread is about, an article about which I linked to in the OP. That definition is, shortly put, "what matters, morally speaking, is that people feel good rather than bad, experience pleasure rather than pain, enjoyment rather than suffering", etc. That could be people generally (altruism) or just oneself (egotism); that axis is a different one from hedonism vs... non-hedonism, for which I'm unaware of a good general word. (Let me know if anyone else is!)

Prefer the other way around. ("Cognitivism"? Not that it matters.) — bongo fury

Not sure what you mean here. "The other way around" from artistic/intellectual/etc pleasure being a proper kind of pleasure more generally would be... pleasure more generally always being an artistic/intellectual/etc pleasure? I don't know what that would mean. That there are no non-artistic/intellectual/etc pleasures?

I would have thought that the most obviously hedonist of the Greek schools was Epicurianism: 'The school rejected determinism and advocated hedonism (pleasure as the highest good), but of a restrained kind: mental pleasure was regarded more highly than physical, and the ultimate pleasure was held to be freedom from anxiety and mental pain, especially that arising from needless fear of death and of the gods.'

That state of freedom from anxiety was ataraxia, I believe. — Wayfarer

Yep, and that's entirely consistent with the kind of thing I'm asking about in the OP.

“Nobody is relevant” sounds quite selfish. — javi2541997

The option reads "Nobody's is relevant"; nobody's experience of pain or pleasure, in context. That includes oneself, so it can't be selfish. It's just a way of saying that pain or pleasure (feeling good or bad, enjoyment or suffering, etc) are not morally relevant, so that people who picked the third option for the first question have an option that applies to them in the second question.

For anyone to say it is irrelevant to morality must have said so with good reason ... I cannot fathom what that is and will be simply down to their personal understanding of what ‘morality’ means. — I like sushi

Myself likewise. I find myself just flabbergasted at the notion of reckoning something as good or bad regardless of (or even in spite of) whether it makes anybody feel good or bad.

Non-egotism, sure: other people matter. But what matters is that they feel good and not bad.

Non-consequentialism, sure: the ends don't justify the means. But what makes a means unjust is a product of the pain it inflicts on others.

Neither of those things (egotism or consequentialism) are part and parcel of hedonism. And if not hedonism, if it's not pain or pleasure, enjoyment or suffering, feeling good or bad, that are the criteria for judging whether something is good or bad, then what is? Just... because someone said so? -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principlesomething more akin to utilitarianism, than hedonism — counterpunch

Utilitarianism is a kind of hedonism. It's a consequentialist altruistic hedonism. (This poll's two questions are about hedonism yes or no, and if yes, altruism yes or no; I'm not asking about consequentialism yes or not at this point). -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principlethe damage done to society by everyone doing whatever they want, would soon undermine individual happiness — counterpunch

“Being happy” or otherwise not suffering is not synonymous with “doing whatever you want”. Hedonism is not necessarily extreme liberalism; consequentialist hedonism can be quite draconian in fact. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principlethe second question is about bodily states of "pleasure" or "pain" (i.e. functional or dysfunctional) in themselves rather than relevant to anything else — 180 Proof

The second question asks “Is it everyone's pleasure or pain that's relevant, or only some people's / your own?”. It’s a followup to the first question: if pleasure (good feelings) and pain (bad feelings) are morally relevant, WHOSE are thus relevant?

Poll questions can only be so long. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleIt’s completely irrelevant, but everybody’s is relevant? How does that work?

-

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesSpeculation is not philosophy

— Pfhorrest

I didn't claim or imply that it is. — 180 Proof

Then I don’t know what you meant by

philosophical speculation — 180 Proof

... more or less, critical rationalism, i.e. letting any possibility float until it can be ruled out, rather than rejecting all possibilities until they can be proven the unique correct one.

— Pfhorrest

Non sequitur. — 180 Proof

Not at all. You could ask an infinite regress of “why is it that...” but at some point someone might stop and say “I don’t know it just seems true to me!” and that’s fine per critical rationalism so long as there remains some way that it could in principle be shown false if it were.

Likewise, you could ask an infinite regress of “why should it be that...” but at some point someone might stop and say “I don’t know it just seems good to me!” and that’s fine too on my account so long as there remains some way that it could in principle be shown bad if it were. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principlelistening to music, mastering an intellectual discipline etc — Wayfarer

I would count the good or bad feelings one gets from those, and emotional states generally, as well within the domain of pleasure/pain/hedonic experience. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleGah I missed a typo, "thing or moral relevance" -> "thing of moral relevance". @jamalrob et al is there any way I can fix that?

-

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesthis is not how the world works. — baker

When talking about how the world should be, saying "but it's not that way" is non-sequitur.

Do you believe in objective morality? — baker

Objective as in universal, non-relative, yes.

Objective as in transcendent, non-phenomenal, no.

I'm about to go into why on each of those in my next thread, though I already have in brief in a much earlier thread.

Because for a psychologically normal person, the Why is supposed to go without saying, be something that the person takes for granted. — baker

"the why" belongs to philosophical speculation — 180 Proof

Speculation is not philosophy, and if you think all can be said about something is unsubstantiated speculation or something else unquestionable and just taken for granted, then you’re just declaring that the question cannot actually be answered, or that the answers cannot be questioned, either of which is merely to give up trying to answer it, which is counter to the first principles of my philosophy, the application of which to morality I’ve already gone over in brief (see earlier thread) and which I’ll be exploring in more depth in my next thread.

Philosophically I'm committed to there not being any (ultimate) 'why that does not beg the question' (precipating infinite regresses) — 180 Proof

There is equal potential for infinite regress in the “how does” question, and the solution to both is the same: more or less, critical rationalism, i.e. letting any possibility float until it can be ruled out, rather than rejecting all possibilities until they can be proven the unique correct one. The application of that principle to morality is three threads away, though it's also already been covered briefly in that earlier thread.

Then you wouldn't be "walking in his shoes" to begin with. You wouldn't be empathizing, you'd be projecting, following your own agenda. — baker

Walking in someone's shoes doesn't at all mean you have to agree with them, it just means you care about their experiences. If they don't care about other people's experience, they might make morally wrong decisions, so you shouldn't agree with them, even though you understand where they're coming from, as you should, because if you don't care about their experience, then you might make the morally wrong decisions too. To approach a universally ("objectively") correct opinion about anything requires accounting for the phenomenal ("subjective") experiences of as close to everyone as you can manage.

If you're already sure you know what's right and wrong, then why randomly empathize with others?? — baker

I'm not already sure I know what is right and wrong, I'm just confident about what the criteria for assessing what's right and wrong are. (Those criteria involve the experiences that everybody has, and Hitler's decisions did not respect those criteria, which is why I judge them wrong; but assessing what would have been right would still have involved considering his experiences too.)

This is the only part of this post or those I'm responding to that's actually on topic to this thread: there are separate issues of how to answer moral questions in principle, and what are those answers given the specifics of the real world. Meta-ethics (moral semantics, moral ontology, moral epistemology, etc) is about the first issue, applied ethics is about the second issue, and normative ethics messily blurs those lines, does both badly, and should be split up among the other two, only the first of which is philosophical, because it's about necessary a priori principles, while the latter is about contingent a posteriori matters, and so beyond the scope of philosophy.

You're not answering my question. — baker

Because it's not the topic of this thread, and also it's a prima facie dumb question like asking "what do numbers have to do with math?" (Credit to my gf who saw your question over my shoulder and said exactly that).

For two, what you're describing sounds more like codependence or borderline personality disorder symptoms. — baker

This sounds like you're lashing out at me suggesting you being scared of non-binary people is a psychological problem of yours, not a social problem of theirs. -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesWould you empathize with Hitler, see things from his perspective, see, how from his perspective, what he did was good and right? — baker

Yes, but not to agree with him, but to understand his deeper motives and find alternate ways of satisfying them that don't so deeply dissatisfy others'.

Extreme egalitarianism? — baker

Yes, otherwise known as altruism. Everyone matters. Everyone.

And what would such extreme empathy have to do with finding out what's good or bad?? — baker

What do you think "good or bad" even mean? Because this just sounds like a bizarre question to me. -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesI think perhaps there's just a misunderstanding. I'm not saying that those fields you're talking about aren't relevant at all in the end, but that they're still only part of one half of the picture, and what I'm talking about in this thread is the insufficiently examined other half of that same picture.

When we're setting out to do anything, there's two things to ask ourselves: why to do it / why should something come to be the case, and how to do it / how does something come to be the case? We've got all of the descriptive sciences, including the ones you're talking about, investigating the second type of question, the "how does", to great results. But we barely have any systemic investigation into the first question, the "why should". That's what I'm on about here. -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesWe established that no-one would disagree that you CAN learn what feels good or bad to other people by “walking a mile in their shoes” etc. The disagreement is about whether it MATTERS TO. And that’s not an implication at this point in the process, that’s a premise now, after having been established way back at the beginning, whether to your satisfactory or not. I have not seen any convincing counter arguments to those foundational principles established way back then, only what amounts to either a misunderstanding of them or the assertion that someone disagrees with them.

The novel idea in this thread isn’t even an implication of those principles, the version of it I’m putting forth merely assumes the rest of my views, but in principle could be adapted to others. That idea in this thread is:

There are two parts to an ethical investigation, the philosophical part of figuring out what we’re asking, what would make an answer correct, and how we apply such criteria; then the part where we actually do that application and come up with specific answers for the real world based on those philosophical principles. Meta-ethics is the first part, applied ethics is the start of the second part, and normative ethics kinda doesn’t fit in there anywhere. But different normative ethical views are on the right track to answering different meta-ethical questions, and the whole sort of project normative ethics is trying to do is really the base layer of what applied ethics should become. -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesThe matter of substantial disagreement is on whether or not experience, everyone’s experiences, are relevant and important and matter, which was covered and argued for many threads ago.

If that is accepted then the rest should follow for anyone who can keep up with the logic (which NB does have novel implications as well as drawing novel connections between disparate well-known things).

If that argument from many threads ago is not accepted then I lost you way back then and pointing out that you (or someone) still disagree with that isn’t getting anyone anywhere. If I lost you (generic you, whomever) way back there then I have no further ideas on how to reach you, so I’m not talking to you anymore. -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesNobody I know of denies that you can, but plenty of people, anyone opposed to altruism or hedonism, denies that it matters to: anti-altruists denying that other people's anything matters, anti-hedonists denying that anybody's appetites matter.

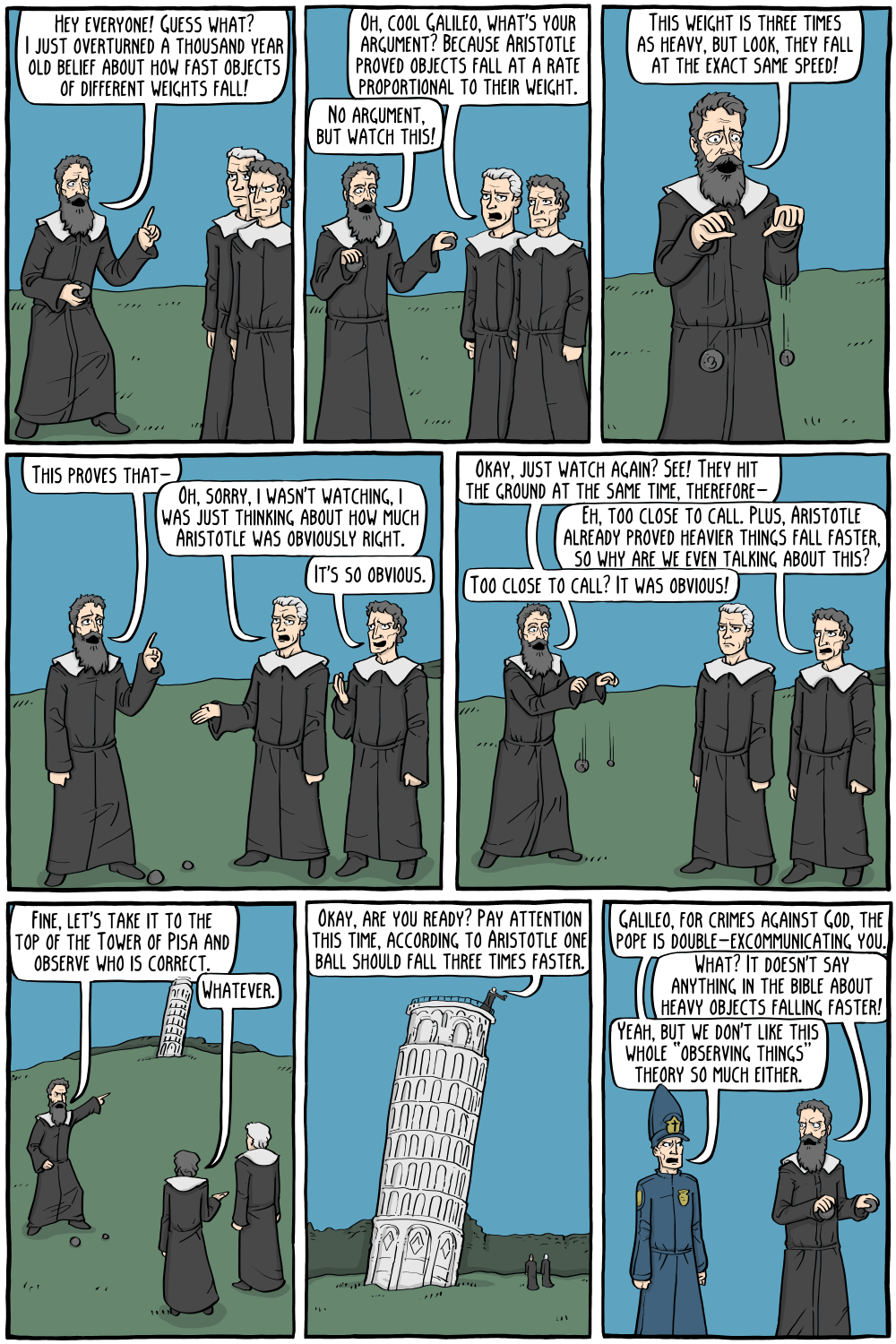

Like how nobody denies that you can look at Galileo dropping his rocks and see for yourself that they land at the same time, but some will talk as though that doesn't matter, because "the senses are deceitful and can't be trusted", something something Plato's cave, shadow puppets, light of reason, etc. -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesSo "ethical science" is like medical science or human ecology (my preferred analogue) or moral psychology ... — 180 Proof

I’m not sure that’s accurate, since AFAIK those fields are empirical investigations, that at most describe what people are like and how they react to various things, in the third person. That’s etic when it comes to other people’s hedonic experiences, although of course all empirical science is emic in the sense that it’s grounded in first-person observations.

But if empirical science were done in an analogous etic way, rather than repeating observations to confirm that things really do look like X is true or false to Y type of person in Z context, we would just write down how Y type of person acts (including what they say) regarding the truth or falsify of X in context Z. That isn’t how we actually do empirical science though; we confirm the reported observations for ourselves.

Likewise, the ethical sciences I advocate aren’t just about watching other people and noting whether person type Y acts like (incl. says) X is good or bad in context Z. They’re about actually confirming those reported experiences ourselves: if Alice says that X feels bad in context Z, ethical scientist Bob should put himself in context Z and see if X actually feels bad, and if it doesn’t, get more people to do the same, and control for other factors of the environment and the phenomenon, until they’ve all amassed a large enough assortment of emic, first-person accounts to all agree, from their first-hand experience, on what really does feel good or bad to what type of person in what contexts.

It's basically the same principle that we use to instill morals into children: "how would you like it if that happened to you?" Except even that is more akin to "imagine what it would be like if...", which is once again not science. It's more like making a child go and experience something they made someone else experience so that they know first-hand, don't just imagine, that it's wrong.

People who have not undergone a certain type of experience may not understand why something or another that causes that type of experience, which is unpleasant to certain people, is bad, in the visceral experiential way that we all know that getting punched in the face is bad without needing any kind of fancy moral code to tell us: it just feels bad!

I'm reminded of a news story I read maybe a decade ago about some congress people challenged to live for a relatively short period of time (a month, or maybe a week?) on a median American's budget. They came back reporting about how it was surprisingly hard, they they couldn't figure out ways to simultaneously make all of their ends meet, like they had to decide which foods not to get at the store so they could afford enough of other foods and still pay bills... and all the hundreds of millions of Americans who live like that their entire lives were saying "Duh! This is why we need help! It sucks to live this way! Now you see!?"

To find out what's good or bad, walk some miles in other peoples' shoes, put yourself in their places, experience for yourself what it's like to go through what they go through, and if necessary figure out what's different between you and them that might account for any differences that remain in your experiences.

It seems like this is simultaneously a principle that everyone must have already learned as children, but somehow also a controversial opinion among learned people; much like empiricism, the radical proposition that we can learn things about the world by looking at it:

-

Is pessimism or optimism the most useful starting point for thinking?But is this really what is meant by pessimism? — Pantagruel

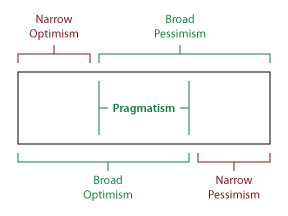

I have been called "pessimistic" by people who want to engage in what I call "narrow optimism", just for calling attention to the possibility of bad things happening. They complain that I "always focus on the negative", by being on the lookout for things that could go wrong. Some people really really just want to believe that everything is going to be fine no matter what and ignore the possible pitfalls because thinking about that makes them feel bad. Those are the counterproductive "narrow optimists" I mean, and the thing that they call "pessimism" (which you rightly call just caution) is what I mean by "broad pessimism". -

Is pessimism or optimism the most useful starting point for thinking?There are productive and counter-productive versions of both optimism and pessimism. Pantagruel's answer above is correct given the counterproductive version of pessimism ("something bad will happen") and the productive version of optimism ("something good could happen"), but one could instead think of pessimism as "something bad could happen" (which is productive) and optimism as "something good will happen" (which is counterproductive).

Assuming that either something good or something bad definitely will happen no matter what you do, or equivalently that either something good or something bad could not happen no matter what you do, is counterproductive, as it leaves you no apparent reason to try to make things turn out better, whether that's because it's all gonna work itself out or because there's no hope. And if you don't try, then there is less likely to be any hope.

I call the productive types of both optimism and pessimism the "broad" forms of them, and the counter-productive types the "narrow" forms (because the counter-productive types are a subset of the productive types). And I advocate embracing the broad, productive forms of both, because that's the only pragmatic way to look at things:

-

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesWhy "satisfy all of our appetites"? And explain what makes that answer both "ethical" and "scientific". — 180 Proof

The "what makes it scientific" part I just answered in response to another comment above (TL;DR: by "appetite" I mean a kind of experience, specifically a hedonic one, basically a kind of "pain" etc; and by "science" I mean an investigation that appeals to actual, contingent, a posteriori experiences, whether those are empirical sensations or hedonic appetites):

So by science in general I mean an investigation that hinges on appeal to experiences, which is therefore a posteriori, and can shed light on contingent matters. In contrast to a philosophical investigation that is entirely a priori, independent of specific experiences, and so can only reach conclusions about what is necessary or impossible.

The distinction between physical or descriptive sciences (the usual sense of "science" today) and the ethical or prescriptive sciences I'm discussing here is the distinction between empirical experience (or sensations) and hedonic experience (or appetites): an experience that inclines one to think or feel that something is or isn't true or real, vs an experience that inclines one to think or feel that something is or isn't good or moral. — Pfhorrest

The "what makes it ethical" part is basically asking for a justification for altruistic hedonism as the correct ethics, and that's a long answer that I'm planning to do another thread on later, but the too-short version is: altruism is the ethical face of universalism, the negation relativism; hedonism is the ethical face of phenomenalism, the negation of transcendentalism; transcendentalism requires dogmatism; and both relativism and dogmatism boil down to different forms of simply giving up on even trying to answer the question. -

Are you modern?'Post-modern' period - commenced with publication of Einstein's General Theory of Relativity 1915. — Wayfarer

[citation needed] -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesI don't see why that is any reason not to include it. — Pantagruel

I'm not excluding it, or saying it shouldn't be done, just that it's not a part of this set of things I'm talking about. -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciences“Emic Ethnography” would be better referred to as just ‘ethnography’ as the former is like saying ‘a dark shade of black’. If not some clarification would be useful. — I like sushi

In an anthropology class I had a long time ago, I was taught that emic ethnography was the newer type, and that etic ethnography had been the usual long before. It might be that all ethnography today is emic, but at least according to that class they're not strictly synonyms.

In any case I kinda didn't even want to use the word "ethnography" there, I just wasn't sure what other noun to attach the adjective "emic" to (the emic vs etic distinction being the main point to make: I'm advocating undergoing the same experiences as others and reporting on those experiences in the first person, rather than just observing or talking to others in the third person), and ethnography seems to be the place it's applied most.

On top of the above there is the niggling issue of defining ‘science’. I’m sure you’ve done this elsewhere, but a reminder of your position is probably worth mentioning in the OP. — I like sushi

I did briefly cover that in the OP, in this paragraph:

ethical sciences – contingent, a posteriori applications of the philosophy of morality and justice – are the bridge to ever more useful businesses, in the same way that the physical sciences are the bridge from the philosophy of reality and knowledge – of which they are contingent, a posteriori applications – to ever more useful technologies. — Pfhorrest

So by science in general I mean an investigation that hinges on appeal to experiences, which is therefore a posteriori, and can shed light on contingent matters. In contrast to a philosophical investigation that is entirely a priori, independent of specific experiences, and so can only reach conclusions about what is necessary or impossible.

The distinction between physical or descriptive sciences (the usual sense of "science" today) and the ethical or prescriptive sciences I'm discussing here is the distinction between empirical experience (or sensations) and hedonic experience (or appetites): an experience that inclines one to think or feel that something is or isn't true or real, vs an experience that inclines one to think or feel that something is or isn't good or moral. -

Philosophy vs. real lifeIt's a well-known trope that famous and powerful people never know who truly likes them and cares about them, because there's always an ulterior motive to be flattering and accommodating even for someone who doesn't like or care about them. This is usually portrayed as a problem that these famous and powerful people don't like having to deal with; they'd like to know that they are genuinely liked, not just being lied to by people who are afraid of them or want something from them.

Likewise, even the famous and powerful would like to know that their views are actually right, and they're not just being constantly lied to by yes-men. (Even this is a trope of its own: a powerful person appreciating the uninhibited honestly of someone, after growing tired of never getting anything but vacuous agreement from everyone).

Rational argument is how they can find out whether they really are right, and so is something to be valued even by those who can appeal to other power to otherwise get what they want. -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesWhat’s an “appetite” that’s not a desire or intention? What are these “hedonic experiences”? — khaled

Appetites or hedonic experiences (same thing as I mean them) are things like pain, hunger, thirst, etc. Not a want for a specific state of affairs to be the case, but just a feeling that calls for something or other to be done. What specifically must be done is always underdetermined by appetites, i.e. there are always various possible ways in principle to satisfy an appetite; the same way that what to believe is always underdetermined by observation. It is precisely that underdetermination of a particular state of affairs that makes it always possible to reconcile them: it's just a creative challenge to come up with some state of affairs that satisfies them all, since no particular states of affairs that might irreconcilably conflict are directly demanded by them. -

The United States Of Adult ChildrenCapitalism is the only economic system there is. — synthesis

You don’t even understanding what the word “capitalism” means.

There are four things to discuss here, two different distinctions:

- 1. Goods and services being exchanged voluntarily.

vs

- 2. Goods and services being exchanged under the coercion of an authority.

and

- 3. The stuff everyone uses to do stuff generally belonging to everyone.

vs

- 4. The stuff everyone uses to do stuff generally belonging to a small class of people.

1 is called "a free market".

2 is called "a command economy".

3 is called "socialism".

4 is called "capitalism".

People like Adam Smith argued for 1 over 2, and never said anything about "capitalism", but said some things suggestive of preferring 3 over 4 too.

People like Karl Marx argued for 3 over 4, and never said anything about "a command economy", but said some things suggestive of preferring 1 over 2 too.

Libertarian socialists are explicitly in favor of 1 and 3 over 2 and 4, and say that you can't have 1 without 3 or vice versa, because 2 will create 4 and vice versa.

People like you don't distinguish between 1 and 4, and just use the word "capitalism" as though it meant 1 only, when what everyone else is actually arguing against is 4. -

Changing screen nameI get autocomplete options when I type names in the @ modal, and I can confirm this guy’s name doesn’t pop up no matter how much of it I type. I can get even get so far as one letter short, and other “Connor” names show up alongside some “Ryan” names, but no “Ryan O’Connor”.

Very likely the apostrophe plus the Javascript that handles the autocomplete not properly escaping usernames. -

Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciencesWhat about descriptive ethics? — Pantagruel

That's just a natural or physical (i.e. descriptive) science when you get down to it, a study of what peoples' ethical beliefs are, rather than a study into which ethical beliefs are the correct or incorrect ones.

I don’t see how any of this tells someone what they should do? It just seems to be cataloguing what people need and want, and the results of that. It reads like the first level is simply psychology, second is economics, third is political science and the last is.... also political science.

I don’t see where ethics comes into the picture. Knowing that people want food, and the consequences of the they all the way to a political level, doesn’t seem to have anything to do with ethics. — khaled

All of this is an application of a meta-ethics, an account of what claims about what people should do mean, what would make such claims correct or incorrect, and how to go about figuring out which claims are correct or incorrect. That's sort of the point of the two threads I intended to do here: that normative ethics as normally conceived of is neither here nor there, it's halfway a claim about which things in particular are good or bad, and halfway an account of how to gauge which things are good or bad. I'm saying that it should therefore be dissolved into the other two fields of "ethics" broadly speaking: a philosophical meta-ethics, which gives an account of how to do applied ethical sciences, in the same way that metaphysics (broadly construed as containing epistemology, ontology, etc) is at the end of the day an account of how to do physical sciences: what do our claims about reality mean, what makes them true or false, and how can we tell which is which?

I thought that the whole thing was too long for a single OP, so I divided it up into two, but since this question came up right away, maybe I should just posted the other OP right now, as a response here, and rename the thread...

On the other hand, I think that the actual general approaches to normative ethics that have historically been developed can be better developed and reconciled with each other if they are instead viewed not as competing answers to the same normative ethical question, but as complimentary answers to the different questions within meta-ethics. The primary divide within normative ethics is between consequentialist (or teleological) models, which hold that acts are good or bad only on account of the consequences that they bring about, and deontological models, which hold that acts are good or bad in and of themselves and the consequences of them cannot change that.

The decision between them is precisely the decision as to whether the ends justify the means, with consequentialist models saying yes they do, and deontological theories saying no they don't. I hold that that is a strictly speaking false dilemma, between the two types of normative ethical model, although the strict answer I would give to whether the ends justify the means is "no". But that is because I view the separation of ends and means as itself a false dilemma, in that every means is itself an end, and every end is a means to something more.

This is similar to how my views on ontology and epistemology (see links for previous threads) entail a kind of direct realism in which there is no distinction between representations of reality and reality itself, there is only the incomplete but direct comprehension of small parts of reality that we have, distinguished from the completeness of reality itself that is always at least partially beyond our comprehension. We aren't trying to figure out what is really real from possibly-fallible representations of reality, we're undertaking a fallible process of trying to piece together our direct sensation of small bits of reality and extrapolate the rest of it from them.

Likewise, to behave morally, we aren't just aiming to use possibly-fallible means to indirectly achieve some ends, we're undertaking a process of directly causing ends with each and every behavior, and fallibly attempting to piece all of those together into a greater good.

Perhaps more clearly than that analogy, the dissolution of the dichotomy between ends and means that I mean to articulate here is like how a sound argument cannot merely be a valid argument, and cannot merely have true conclusions, but it must be valid – every step of the argument must be a justified inference from previous ones – and it must have a true conclusion, which requires also that it begin from true premises.

If a valid argument leads to a false conclusion, that tells you that the premises of the argument must have been false, because by definition valid inferences from true premises must lead to true conclusions; that's what makes them valid. If the premises were true and the inferences in the argument still lead to a false conclusion, that tells you that the inferences were not valid. But likewise, if an invalid argument happens to have a true conclusion, that's no credit to the argument; the conclusion is true, sure, but the argument is still a bad one, invalid.

I hold that a similar relationship holds between means and ends: means are like inferences, the steps you take to reach an end, which is like a conclusion. Just means must be "good-preserving" in the same way that valid inferences are truth-preserving: just means exercised out of good prior circumstances definitionally must lead to good consequences; just means must introduce no badness, or as Hippocrates wrote in his famous physicians' oath, they must "first, do no harm".

If something bad happens as a consequence of some means, then that tells you either that something about those means were unjust, or that there was something already bad in the prior circumstances that those means simply have not alleviated (which failure to alleviate does not make them therefore unjust). But likewise, if something good happens as a consequence of unjust means, that's no credit to those means; the consequences are good, sure, but the means are still bad ones, unjust.

Moral action requires using just means to achieve good ends, and if either of those is neglected, morality has been failed; bad consequences of genuinely just actions means some preexisting badness has still yet to be addressed (or else is a sign that the actions were not genuinely just), and good consequences of unjust actions do not thereby justify those actions.

Consequentialist models of normative ethics concern themselves primarily with defining what is a good state of affairs, and then say that bringing about those states of affairs is what defines a good action. Deontological models of normative ethics concern themselves primarily with defining what makes an action itself intrinsically good, or just, regardless of further consequences of the action.

I think that these are both important questions, and they are the moral analogues to questions about ontology and epistemology: fields that I call teleology (from the the Greek telos meaning "end" or "purpose"), which is about the objects (in the sense of "goals" or "aims") of morality, like ontology is about the objects of reality; and deontology (from the Greek deon meaning "duty"), which is about how to pursue morality, like epistemology is about how to pursue reality.

In addition to consequentialist and deontological normative ethical models, there is a third common type, called aretaic or virtue ethics, which holds that morality is about the character, the internal mental states, of the person doing the action, rather than about the action itself or its consequences. I hold that that is also an important question to consider, and that that question is wrapped up with the question of what it means to have free will.

And lastly, though it's not usually studied as a philosophical division of normative ethics, there are plenty of views across history that hold that morality lies in doing what the correct authority commands, whether that be a supernatural authority (as in divine command theory) or a more mundane authority (as in some varieties of legalism). That concern is of course wrapped up in the question of who if anyone is the correct authority and what gives their commands any moral weight, which is the central concern of political philosophy.

So rather than addressing normative ethics as its own field, I prefer approaching those four questions corresponding to four kinds of normative ethical theories as equally important fields:

- teleology (dealing with the objects of morality, the intended ends)

- deontology (dealing with the methods of justice, what the rules should be)

- the philosophy of will (dealing with the subjects of morality, who does the intending), and

- the philosophy of politics (dealing with the institutions of justice, who should enforce the rules).

I would loosely group these together as "meta-ethics" in a slightly different than usual sense, they being the questions necessary to answer in order to pursue the ethical sciences I propose above; in a way analogous to how the fields of...

- ontology (about the objects of reality)

- epistemology (about the methods of knowledge)

- the philosophy of mind (about the subjects of reality), and

- the philosophy of academics (about the institutions of knowledge)

... – which we might likewise group together in a slightly unusual sense as "meta-physics" – address the questions necessary to answer in order to pursue the physical sciences.

In general, I view the correct approach to prescriptive questions about morality and justice to be completely analogous to, but also entirely separate from, the correct approach to descriptive questions about reality and knowledge. This is different from views that hold that one set of questions reduces entirely to the other set of questions, like both scientism (which reduces prescriptive questions to descriptive ones) and constructivism (which reduces descriptive questions to prescriptive ones).

But it is also different from views such as the "non-overlapping magisteria" proposed by Stephen Jay Gould, who held that questions about reality are the domain of science, with its methodologies, while questions about morality were entirely separate in the domain of religion, with its wholly different methodologies.

I hold, like Gould, that they are entirely separate questions, but that perfectly analogous, broadly-speaking scientific, methodologies can be applied to each, and that religious methodologies have historically been (wrongly) applied to both of them as well. This is largely because of my views that prescriptive assertions and opinions are generally analogous in every way to descriptive assertions and opinions, differing only in a quality called "direction of fit".

I'm planning on doing more threads in the near future where I will lay out in more detail my views on those fields of teleology, deontology, will, and politics, that I hold analogous to the fields of ontology, epistemology, mind, and academics. But for now, I will leave off here with a broad overview of the analogous process that I advocate, of which the ethical sciences detailed in the OP are the application:

When it comes to tackling questions about reality, pursuing knowledge, we should not take some census or survey of people's beliefs or perceptions, and either try to figure out how all those could all be held at once without conflict, or else (because that likely will not be possible) just declare that whatever the majority, or some privileged authority, believes or perceives is true.

Instead, we should appeal to everyone's direct sensations or observations, free from any interpretation into perceptions or beliefs yet, and compare and contrast the empirical experiences of different people in different circumstances to come to a common ground on what experiences there are that need satisfying in order for a belief to be true.

Then we should devise models, or theories, that purport to satisfy all those experiences, and test them against further experiences, rejecting those that fail to satisfy any of them, and selecting the simplest, most efficient of those that remain as what we tentatively hold to be true.

This entire process should be carried out in an organized, collaborative, but intrinsically non-authoritarian academic structure.

When it comes to tackling questions about morality, pursuing justice, we should not take some census or survey of people's intentions or desires, and either try to figure out how all those could all be held at once without conflict, or else (because that likely will not be possible) just declare that whatever the majority, or some privileged authority, intends or desires is good.

Instead, we should appeal to everyone's direct appetites, free from any interpretation into desires or intentions yet, and compare and contrast the hedonic experiences of different people in different circumstances to come to a common ground on what experiences there are that need satisfying in order for an intention to be good.

Then we should devise models, or strategies, that purport to satisfy all those experiences, and test them against further experiences, rejecting those that fail to satisfy any of them, and selecting the simplest, most efficient of those that remain as what we tentatively hold to be good.

This entire process should be carried out in an organized, collaborative, but intrinsically non-authoritarian political structure. -

Religions : education :: states : governance -- a missing subfield of philosophy?So, on to the last part of this thread:

Despite the utopian ideals detailed above, I recognize also that we should not let perfect be the enemy of good, and that the choice should not be between either a perfectly functioning freethinking educational system or no educational system at all, leaving in the latter case a power vacuum for the worse kinds of religions to spring up unopposed. So it seems reasonable to me that there be in place a slightly-less-ideal, less freethinking, but for the same reason more stable system of education in place already in case the ideal one should fail; say something comparable to the most democratic of religions, proselytizing a dogma of what is most commonly and generally believed.

It should wherever possible allow the ideal freethinking solution to function and stay out of its way, and only step in to ameliorate the gravest failures that would otherwise result in a collapse to something even worse than such a democratic dogma. It may in turn be prudent to have more than just this one tier of such failsafe in place, to ensure that wherever a better system of education fails, it fails only to the next-best alternative, rather than failing immediately to the worst alternative; say a Pope-like figure elected through direct democratic vote, empowered only to re-establish a functional democratic religion, which in turn is empowered only to re-establish functional freethinking education.

I think that this kind of evolution from mystery religions toward freethinking proselytism is itself a natural progression of rational educational systems looking to preserve themselves. Authoritarianism and hierarchy may form the default form of religion, but such a religion will survive longer if it asks its congregation what they believe, and shares with them the knowledge it has accumulated, naturally inclining such authoritarian, hierarchical religions to evolve a layer of freedom and openness. Such a populist religion can then most easily appease the most people in its congregation if it simply lets them interpret their religion how they think best, and lets them exchange their own reasons for those interpretations instead of trying to do so itself, adding a layer of freethought.

Thus, the lazy selfish epistemic authority, acting in its own self-interest, naturally devolves epistemic power to its congregation; and a lazy selfish congregation, acting in its own self-interest, naturally devolves epistemic power toward more freethinking ideals; though I don't expect that this process would naturally result in the complete abolition of religion on its own.

A social discourse may in that way find itself over time sliding up and down the scale between the worst authoritarian dogma and the best freethought, depending on how well its participants manage to operate within the different possible educational systems along that scale. Because in the end, it is inherently impossible to force a people to think freely. How good of an educational system a society will support ultimately depends entirely on how much the people of that society genuinely value knowledge, because that educational system is made of people, and it is ultimately their collective pursuit of knowledge that determines how well-educated their society can be.

How exactly to help contribute toward getting enough people to pursue knowledge, reality, and truth more generally, will be the topic of a later thread. -

Non-binary people?I did, and the notion that someone who otherwise has no actual power over you could just make something up (completely setting aside whether it's actually made up) and thereby wield something worth being afraid of over you suggests a problem on your end.

-

Non-binary people?A few years back, when some young-ish actress (I won't mention her name for fear of revenge) who officially goes as "non-binary" declared herself as such, you know what I felt? Fear. — baker

Sounds like you need some professional help then. I'm sorry for your condition.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum