Comments

-

The United States Of Adult ChildrenOf course there is such a reason: safety. Since time immemorial, people have strived to amass wealth in an effort to guarantee as much safety for themselves as possible. — baker

That’s reason to accumulate savings enough to last you a lifetime, sure. But that is still far less that what billionaires accumulate. -

Religions : education :: states : governance -- a missing subfield of philosophy?So, how would you overcome the inabilities of the general public to understand specialized information? — jgill

Basically, by creating a ladder. Making more basic education available to people makes them more capable of understanding more advanced information.

But of course not everyone will be able to be a thorough expert on absolutely everything. All that’s really important is that they be up with the most current broad strokes across the board, the big picture so to speak.

Do you mean new discoveries in math must be promulgated to the general public and not kept locked away in incomprehensible journals for fellow experts? — jgill

In a sense, yes. As those new discoveries are corroborated by fellow experts the impact of them on the field as a whole should make its way into the tertiary sources that the general public learn from, and updates to those sources should be disseminated to the general public even if they’re not actively engaged in a course of training. It’s basically science news, if you count math as a science (I’m thinking much more about natural or physical sciences in most of what I’m writing here, descriptions of how the world is). Basically we need good science news. -

The United States Of Adult Childrenso do as the Good Book says, and criminalise usury — Banno

That is more or less my position, though not criminalize per se but invalidate contracts thereof, without which it has no force. (Also, religious prohibitions of usury usually fail to recognize property rent as essentially the exact same thing, which gives an obviously loophole, which is how medieval Catholic and current Muslim banking operates).

Thing is though that once there’s no way to make money just by owning other people’s stuff and charging them to use it, there’s pretty much no motive to own more than you use yourself anymore, and so no reason to be a supermultibillionaire at all.

Thus through the invalidation of usury we create socialism, by having the state do less rather than more. -

The United States Of Adult ChildrenA few billionaires who had no more say in government than you and I would not be a problem. — Banno

Unless the billions of dollars of capital they owned were our homes and businesses, making us all de facto subservient to them if we want access to the things we need to survive, even if they don't have any de jure authority over us. -

The United States Of Adult ChildrenIt's not capitalism that is at fault. It's simply lack of equity in the distribution of wealth. — Banno

That's precisely what capitalism is. Wealth is capital, and capitalism is when capital is held entirely by a small class of people, making the rest subservient to them. If wealth was equitably distributed -- and somehow stably so, so it doesn't just collapse back into few hands immediately -- that would be socialism, the ownership of capital by the people generally rather than a small elite class. -

The United States Of Adult ChildrenUnless one can achieve financial independence and intellectual autonomy, individuals will always be controlled (from without) resulting in the loss of essential freedoms (a great American tragedy). — synthesis

Yep, which is why capitalism needs to be abolished, as that is what keeps so many from attaining financial independence. -

Religions : education :: states : governance -- a missing subfield of philosophy?I'm going to continue with the new parts of this thread that I was previously going to make into new threads, but don't let that disrupt the ongoing conversation... hopefully this sheds further light on my position, if that helps:

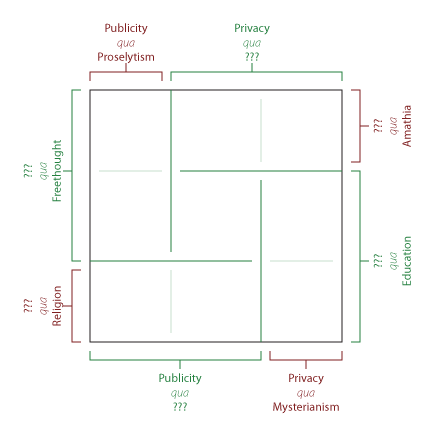

Maintaining a generally equal level of information between all the members of society is of utmost importance to making sure that such a freethinking educational system can continue to function properly, because if some people have so much more information than others, they have the ability to persuade those others to believe whatever they believe (without those others having the informational resources to properly criticize what they are told), and so begin to wield effective epistemic authority which can then easily grow into a proper religion. Because of this interdependence between liberty of thought and equal access to information, freethinking education requires what we might call a proselytizing approach to information distribution: when new information is discovered, that news must somehow become widespread, and not remain only known to those who discovered it and those closest to them.

This does not necessarily mean preaching a dogma, demanding that everyone must adopt the new findings; that would obviously be a religion, and so not freethinking. "Proselytizing" as I mean it here means only that the populace cannot be divided into those who have access to the information and those who don't. In contrast, such a division of society into those who know the important information and those who don't is what is called in religious studies "mysterianism", which many ancient religions practiced, having the greatest supposed "truths" known only to the innermost circle, with everyone else in the religion dependent on them for guidance.

Medieval European Christianity had shades of this as well with their holy text being available only in Latin and so incomprehensible to most of the congregation, making them dependent on their priests for an interpretation of the text; and newer religions like Scientology and some Wiccan traditions once again go back to a fully mysterian model as well. Even in the generally freethinking educational system that dominates in the western world today, limited public access both to educators and to research journals creates exactly the kind of wall between those who have access to information and those who don't that freethought cannot flourish in.

Freethought definitionally cannot survive alongside mysterianism, as those who held privileged access to information would merely become in effect the new religious leaders, with nobody else able to double-check and properly criticize them. Similarly, truly open proselytism, in the sense that I mean it here, cannot in practice survive alongside a religion, as whoever leads the religion controls all the information that is allowed to be disseminated, and can silence as heretical any ideas that threaten their epistemic authority (as pre-modern examples of religions silencing scientific research clearly show).

Despite the interdependence of liberty of thought and equal distribution of information described above, there is a history of both freethinking individuals secreting away the results of their research, and of course of religious proselytism, epitomized especially in Abrahamic religions like Christianity and Islam. By considering liberty of thought and equal distribution of information independently, we can create a two-dimensional spectrum of academic systems, on which such different approaches and my own position can be located. I do not actually advocate for absolute liberty of thought or absolutely equal distribution of information, but rather hold what I view to be a centrist position on both topics.

In one corner of this spectrum are the ancient mystery religions, and newer religions like Scientology that revive that mysterian approach. In another are the more familiar modern proselytizing religions. In a third corner are the freethinking researchers who withhold the information they discover from free public access, including both the likes of medieval alchemists secretly investigating ways to turn lead into gold, and the likes of modern trade-secret corporate research, and paywalled, limited-access research journals. In the last corner far opposite mystery religions would be positions that are so in favor of freedom of thought that they would oppose even non-religious education or even personal critical argument, opting for a complete "agree to disagree" attitude, and so in favor of distribution of information that they have no respect for the privacy of information that is not relevant to the public discourse.

I consider my position centrally located on this spectrum, respecting privacy and education while opposing mystery and religion.

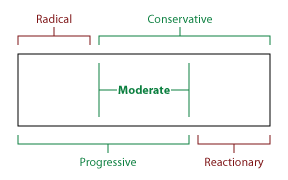

This academic spectrum is analogous to two-dimensional political spectra that juxtapose an axis of political authority or liberty against an axis of the equality or hierarchy of wealth distribution. I will address such a political spectrum in another thread later, wherein I will also discuss the relationship of the terms "conservative", "moderate", and "progressive" to such a spectrum. My view is that those terms do not refer to one of the axes of such a two-dimensional spectrum, but rather form a third axis entirely, one not about where on that two-dimension spectrum one's ideal system would fall, but how one approaches change toward their goal, wherever on the spectrum it should be. Those terms are equally applicable to a third dimension to this academic spectrum here.

In this topic as in that, I hold that the proper referent of "conservative" is someone who is cautious about change, if not completely opposed to it. Conversely I hold that the proper referent of "progressive" is someone who pushes for some change, if not complete change. And I hold that the proper referent of "moderate" is someone who is both conservative and progressive, pushing for some change, but cautious change. Those progressives who are not moderate, pushing for complete change, are properly called "radicals", and those conservatives who are not moderate, completely opposing all change, are properly called "reactionaries".

I consider myself not only a true centrist on the full spectrum described above, but also a moderate in this sense of conservatively progressive, neither radical nor reactionary. I do not view either change or stasis as inherently superior to the other, for both creation and destruction are kinds of change, and both preservation and suppression are forms of stasis, suppression negating creation just as preservation negates destruction; and it's not even inherently superior to create and preserve than to suppress and destroy, for inferior things can be created or preserved, in the process destroying and suppressing superior things, in which case it would be superior to suppress or destroy those inferior things so as to preserve and create superior ones. I support either change or stasis as they foster superior results, neither unilaterally over the other. -

Tax parentsI disagree with your definition of a state, preferring the usual political science definition of "a monopoly on the legitimate use of force". A society doesn't need any claimed monopoly on the use of force to recognize claims to property. This doesn't change the fact that assignment of ownership to properties is a social construct. For analogy: the meaning of words is a social construct, words mean what they mean only because a linguistic community agree to use them that way, but that doesn't have to entail that there is some central authority on the meaning of words.

I actually just had a thread on this (the meaning of words thing), and will be doing one on the analogous property-rights topic eventually too. -

Tax parentsEntitlement is a social construct — unenlightened

Even if so, "society" and "state" are not synonyms. -

Tax parentsFWIW I don't agree with Bartricks' conclusions here but I think the quality of argumentation against him in this thread is just awful.

Philosophical anarchism (the view that the state has no right to command, its subjects have no duty to obey, so the only rights and duties anybody has are the same ones they'd have in the absence of any state) is a pretty well-known position covered in any intro to political philosophy, usually alongside Hobbes, Rousseau, and Locke as archetypes of the three main alternatives.

You can disagree with it if you like, of course, but OP is clearly taking it as a premise and then deriving conclusions from that premise, and that derivation is clearly meant to be the topic here, not the premise itself.

If you insist on debating the premise anyway, try giving an argument against it instead of just saying the equivalent of "nuh uh" or acting like this is some novel complete nonsense that nobody in their right mind would legitimately defend. -

Non-binary people?I think you're being sarcastic, but I still want to note that it's actually a recent phenomenon (post-WWII) for men in general (not in the military) to keep their hair short (it's all because of military fetishism), and a similarly recent phenomenon for women in general (not the wives of wealthy lords) to avoid wearing trousers (because most women had to work, and all work was manual labor, and skirts or dresses are impractical for manual labor).

-

Religions : education :: states : governance -- a missing subfield of philosophy?I don't know what point you're trying to make here. College algebra is under the umbrella of general education, yes. And that is something that is available to the general public, albeit not all of them -- which is a critique I would have of the current system too, at least undergraduate education should be available to everyone. At least at my colleges, there were "general education" requirements in common to all undergraduate degrees, regardless of major, and that's the kind of thing I'm talking about, though not specifically that. Just anything that's meant to be a recounting of the current consensus of experts, rather than specialty studies for people trying to become experts themselves, dealing in matters where there isn't yet consensus.

-

Non-binary people?I'm nonbinary myself so I'm not arguing against calling people "they" or anything like that (though I don't care about pronouns at all, for myself). And I do recognize that sex is not a binary thing either. I'm just noting the distinction between sex and gender. There are physical sexes, in addition to social genders.

-

Non-binary people?social distinction - male and female — Banno

Male and female are the physical distinction, it’s man and woman that are the social abstraction therefrom. -

Religions : education :: states : governance -- a missing subfield of philosophy?I think you're misreading some kind of of nefarious motive in here. The point of this is explicitly to be anti-authoritarian, but it sounds like you're suggesting that I want something made more authoritarian, and I don't see why.

Say you're a high school student, or an undergrad in college -- you know, general education, like the general public gets already. You attend a class where a teacher teaches from a textbook sourced from many different places by other people, not just his own original research -- that part is pretty normal already. Then someone else at the school administers and grades your tests to see if you've successfully learned the material as laid out in the textbook -- this is pretty much the only part we don't already do.

What's so scary or Soviet about that? -

Non-binary people?Non-binary people aren't necessarily genderless. That's just one specific non-binary identity, "agender". Non-binary is an umbrella term encompassing all gender identities besides the two binary ones, "man" and "woman". Bigender and pangender are two other types of non-binary, for example.

Also, who is dictating what to whom? Who wants/opposes the denouncing of all gender? -

Religions : education :: states : governance -- a missing subfield of philosophy?And this pastor would be . . . . . . . . a philosopher? — jgill

Not necessarily, though possibly. The job would have basically the same requirements as a general ed teacher. Someone with a wide breadth of knowledge, the ability to find good sources of deeper knowledge to pass on, and the ability to be remain neutral in disputed matters and share the arguments from all sides with those coming to him looking for answers. I hadn't thought about it but now that you bring it up it does seem like people who are good at philosophy would also likely be good at this job, but I definitely don't mean the job to be just for philosophers.

Regarding the separation of teaching, testing, and research, your response is similar to saying that sometimes it could be better if there weren't a separation of powers in government, because then a benevolent dictator could actually get some good stuff done instead of getting bogged down in all the bureaucracy. That is certainly true, but it also means that a bad dictator would go completely unchecked. The separation of powers is there for safety, to make sure that teachers don't end up as effectively priests.

Graduate studies are somewhat different, because that's on the road to becoming a researcher oneself, so it makes perfect sense that one would basically apprentice to other researchers. I'm talking about general education for the general public, not experts-in-training under the wing of other experts. -

Religions : education :: states : governance -- a missing subfield of philosophy?Surely, in the last century we may saw a move away from the academic elite having the ultimate say about knowledge and a move towards a more lively open exchange of ideas. — Jack Cummins

Yes, but we’ve also seen a very problematic disconnect from a “common reality”, with disparate parts of society holding completely different views on basic facts and even on how to agree on what the facts are. That’s the problem with NOT having shared social institutions of knowledge.

Ultimately, do you think that your academic elite process of peer review would accept such a site as this, or would it seek for it to be under the control and governance of the academic 'experts'? Also, would there be more censorship of views and ideas which the academic hierarchy saw as 'false'? — Jack Cummins

I’m certainly not advocating censorship of any kind, and I think that a properly functioning academic structure would have to engage with the common people (like us) or else it starts to become just a religion and then that causes the exact same problem described above. I think our current version of such an academic system does not engage with the common people enough, which is partly responsible for the current crisis of “post-truth”, and that’s partly because of the missing “pastor” role I advocated earlier.

This once again segues perfectly into the next thing I was going to post anyway, so here that is...

In the absence of good education of the general populace, all manner of little "cults", for lack of a better word, easily spring up. By that I mean small groups of kooks and cranks and quacks each with their own strange dogmas, their own quirky views on what they find to be profound hidden truths that they think everyone else is either just too stupid to wise up to, or else are being actively suppressed by those who want to hide those truths from the public.

Meanwhile, those with greater knowledge see those supposed truths for the falsehoods that they are, and can show them to be such, if only the others could be engaged in a legitimately rational discourse. But instead, these groups use irrational means of persuasion to to ensnare others who do not know better into their little cults; and left unchecked, these can easily become actual full-blown religions, their quirky little forms of ignorance becoming widespread, socially-acceptable ignorance, that can appropriate the veneer of epistemic authority and force their ignorance on others under the guise of knowledge.

Checking the spread of such ignorance by challenging it in the public discourse is the role of the public educator. The need for that role would be lessened if more people would actively seek out education from teachers or pastors as I have described them above, but not everyone will seek out their own education and so some people will continue to spread ignorance – and even those who do seek out their own education may still accidentally spread ignorance – and in that event, there need to be public educators to stand against that. But that then veers awfully close to proposing effectively another "religion" to counter the growth of others.

I think there is perhaps a paradox here, in that a public discourse abhors a power vacuum and so the only way to keep religions, institutions claiming epistemic authority, at bay, is in effect to have one strong enough to do so already in place. But I think there is still hope for freedom of thought, in that not all religions are equally authoritarian: even within religions as more normally and narrowly characterized, some have their dogma handed down through strict decisions and hierarchies, while others more democratically decide what they as a community believe. I think that the best that we can hope for, something that we have perhaps come remarkably close to realizing in the educational systems of some contemporary societies, is a "religion", or rather an academic system, that enshrines the principles of freethought, and is structured in a way consistent with those principles.

Such a system of freethinking education is somewhat analogous to how, in my earlier thread on philosophy of mind, I held that "mind" in one sense is present in all matter, and neither something beyond matter that imposes itself upon matter, nor something that spontaneously arises from certain configurations of matter, but nevertheless something that can be refined by certain configurations of matter; and proper mind per se requires such configurations of matter and doesn't exist in just any random amalgam of matter, but nevertheless still consists of nothing above or beyond simply refined arrangements of the same fundamental "mind" omnipresent in all matter.

So too, here I hold epistemic "authority" to be present in all people, and neither something beyond people that imposes itself upon people, nor something that spontaneously arises from certain configurations of people, but nevertheless something that can be refined by certain configurations of people; and proper education requires such configurations of people and doesn't exist in just any random amalgam of people, but nevertheless still consists of nothing above or beyond simply refined arrangements of the same fundamental "authority" omnipresent in all people.

The ideal form of such a system of education would, I think, see the pastor role described above as the central figure, to whom laypeople come as students with questions and arguments to be resolved. Those pastors then turn, on the one hand, to the authors of tertiary sources for their knowledge, who in turn turn to authors of secondary sources, who in turn turn to the authors of primary sources; while on the other hand the pastors turn to teachers and to public educators to better inform those laypeople coming to them as students.

When there is an argument between two people who cannot mutually agree on one pastor to resolve their conflict, they can each call upon their own separate pastors to step in and resolve the argument between themselves. If need be, if they cannot reach an agreement even with their greater knowledge than their students, those pastors can turn to yet another mutually agreed upon pastor to resolve the resulting conflict between them, or else escalate further on, until at some point the argument is escalated to some parties who can work out an agreement on the matter between them, or to some mutually agreed upon arbiter who can decide the matter, and in either case then pass the decision back down the chain; unless, in the worse case scenario, an irreconcilable rift in the public discourse is discovered, in which case there is no perfect solution regardless of the system of education we have in place. -

Religions : education :: states : governance -- a missing subfield of philosophy?Actually this segues perfectly into the next bit I was about to post anyway:

Still aside from that reactive pastor role, I hold that it is also important to have, as many societies already do, more proactive roles of teachers and public educators. The role of the teacher, as distinct from the pastor, is to actively guide their students to believe things that are probably true, according to those same reference works like textbooks, rather than merely to be there to answer questions and settle arguments as they come up. The teacher provides the students with answers to questions they hadn't even thought to ask yet, and in doing so hopefully helps to prevent arguments from coming up between them in the first place.

To keep this teacher role from becoming too authoritative, though, to keep it from becoming mere indoctrination of one person by another, I think it's important to maintain a separation of the educational roles of teaching, testing, and research, much as in governance it is important to maintain a separation of powers between the executives, judiciary, and legislature. A teacher should not be teaching to texts that they wrote themselves, nor testing their own students on how well they have learned what the teacher wanted them to learn; and neither should the one doing the testing be the author of the text against which the students are tested.

Rather, the text should be a result of the global research process detailed earlier in this essay; accordance with it should be tested by someone like the pastor role described above, someone well-versed in that text; and the teaching of that text to the students should be done by a separate party, teaching to the same text as the person who will later test them, but independent of that testing. In this way the teacher cannot, upon doing their own testing, simply pass those students who they find saying things the teacher approves of and fail those who disagree, but must correctly teach an independent text that someone else, also independent of the authorship of that text, will test them against; and in this way no person involved in the education can exercise unbridled epistemic authority over their students.

Another teacher-like role, but even more proactive still, is that of public educator, who rather than guiding only those students who come to them seeking education – that being still a reactive process in a way – instead looks out over the public discourse and speaks out against falsehoods where they see them, as well as spreading true information to those who may not necessarily be looking for it. Newspapers and the like fall into this category as well as more individual agents. This begins to veer dangerously close to the public educator asserting their own epistemic authority over others, and to make sure that it does not come to that, this process must wind up turning to an independent, mutually agreed-upon "pastor" figure to settle the resulting argument, by reference to still-more-independent reference works that are the product of the global research project detailed earlier.

But I think that it is important to have such public educators going out and contesting falsehoods in the public discourse, making sure there is an argument about them and they don't just go unchallenged, even as dangerously close to authoritarianism as that might veer, because freethought is by its very anti-authoritarian nature paradoxically vulnerable to small pockets of epistemic authority arising out of the power vacuum, and if that instability goes completely unchecked, it can easily threaten to destroy the freethinking discourse entirely and collapse it into a new, epistemically authoritarian regime; a religion in effect, even if not in name. -

Religions : education :: states : governance -- a missing subfield of philosophy?I'm not suggesting that anything be done differently with regard to academia than is done today, but just outlining the ideals of the modern academic process -- which @jgill confirms are mostly accurate (thanks, and yeah, I acknowledge that in practice we often fail to live up to these ideals) -- and contrasting this with the religious model of unquestionable truth handed down from on high... but also with the complete abandonment of any structured pursuit of truth, for reasons I'll go into soon.

NB that "religion" in this context is not a subject matter but a methodology; I'm not saying secular academia should go into the business of making pronouncements about God etc, but that the methods of secular academia are better ways of investigating any subject matter than the ways that religion "investigates" anything... and also, better than not having any structured social institutions of knowledge at all.

The overall thesis of this thread is that opposing religion (authoritarian institutions of supposed knowledge) doesn't mean abandoning all institutions of knowledge, and there can be education without religion. That claim on its face is pretty obvious to moderns, so mostly I'm drawing attention to the relationship between education and religion: that education is in a sense the thing that religion is nominally in the business of, telling people what supposedly is or isn't true or real, spreading supposed knowledge... and so that secular education is just a non-authoritarian version of what religion is nominally for.

Or conversely: that secular education, if made authoritarian, ends up becoming indistinguishable from religion, even if the subject matter that it talks about has nothing to do with God etc.

But also, wrt "pastors", that there is an educational role that religion fulfills that secular education does not, once again not in regards to subject matter, but methodology: I can't just pop down to the local school and float my questions about science etc to some highly-educated guy whose job it is to answer questions about that stuff, or settle disputes between people who disagree about that stuff, etc, the way that one could pop down to the local church to ask some questions about what one's religion has to say about the origins of the universe or whatever. -

China spreading communism once the leading economic superpower?these people, members of the CCP, genuinely believe that they are socialists — ssu

And "anarcho-capitalists" genuinely believe that they are anarchists, but that doesn't make it so.

I don't really care about any west-vs-east rhetoric, but as it happens the people who coined the concept of socialism lived in the west, so if some people in the east decide to do things in a contrary way but still call it "socialism" then any conflict there is their doing, not that of anyone who sticks to the original definitions and just happens to live in the west.

Those policy points are very clearly and unapologetically authoritarian, which is not only completely contrary to the original (libertarian) socialism, but even contrary to the stated end-goal of Marxism, and is the reason why Marxism(-Leninism) consistently fails to actually achieve socialist ends:

You simply cannot have authority without hierarchy, or vice versa; nor conversely equality without liberty, or vice versa; so trying to force equality through authority (rather than just stopping authorities from propping up hierarchies) is doomed to fail, just like trying to abolish authority while allowing hierarchies to persist (as "anarcho-capitalists" do) is doomed, because hierarchies will inevitably create authorities and vice versa. -

Philosophical Methodology or 'ologiesI'm not clear if you're asking for a clarification on what the differences are between Analytic and Continental philosophy, but if you are: I would sum it up as that Analytic philosophy is focused mostly on linguistic and generally abstract aspects of philosophy, with a heavy focus on precision, rigor, and professionalization, while Continental philosophy is focused instead on experiential or phenomenological lived experience and personal applicability to getting through life well, with a comparable focus on breadth and holism rather than narrow isolated problems.

In an old thread of mine someone made another very nice comment summing it up:

The distinction is not just one of subject matter or the overall approach to subject matter, but very importantly, it's a difference of style, of methodological focus, and of expression preferences. Analytic philosophy tends towards tackling things with a relatively narrow focus, one thing at a time, with a preference for a plain, usually rather dry, more or less scientific and/or logical approach. Continental philosophy tends towards a much broader, "holistic" focus, where it tries to tie together many threads at once, with a preference for a far more decorative, looser/playful approach to language. Both sides tend to see the other side as approaching things in a way that doesn't really work/doesn't really accomplish what we're trying to accomplish as philosophers. Those with a continental preference tend to see analytic philosophy as too dry, too boring, too narrow, pointless, mind-numbingly laborious, etc. Those with an analytic preference tend to see continental philosophy as too flowery, inexact, sometimes incoherent, too ready to make unjustified assumptions, etc. — Terrapin Station -

Religions : education :: states : governance -- a missing subfield of philosophy?I guess I'll just continue the series then:

Aside from that multi-tiered process of research just described to produce an alternative to traditional holy texts, an entirely different but valuable social role that religious education has but secular education largely seems to be lacking is that of what we might call the "pastor". Apart from its religious meaning, that is a Latin word roughly equivalent to the English word "shepherd", with etymological roots relating to nourishing and protecting. So by that word in this context I mean a generally smart and knowledgeable person who is well-versed in the "authoritative" texts – a religion's holy book in the traditional role, but the tertiary reference books described above in the secularized version – to whom laypeople can come if they have individual questions about what is real, or to whom parties in a dispute about that can come for mediation and adjudication.

The answers given by such a person should not to be taken on their own personal authority, but on the "authority", such as it is, of the entire global process leading to the production of the reference works to which the pastor refers for their answers. Such pastors should be free to choose the reference works that they find best to use in this process, and individuals or disputing parties coming to them for answers or mediation should be free to choose pastors that they find best to use for their purposes, including for the reason of their choice of reference works. Furthermore, the reference works should not be taken by the pastors as infallible, and in each case it should be possible in principle – though increasingly more difficult in practice over time – to successfully challenge the claims of the reference works, and in doing so force a revision to them.

In this way the entire process remains technically non-authoritative, with lay people merely choosing to invest those who they judge to be smarter and more knowledgeable than themselves with a transient semblance of authority to help them better figure out what to think for themselves, or to settle arguments that they cannot settle between themselves.

(How to resolve cases where different parties to the same dispute appeal to different pastors for mediation will be addressed later.) -

TaxesWell, with that mindset, I think nobody would rent anything and we would often have to spend way more money buying something. The benefit of being able to rent is that sometimes you need to use something for a short amount of time and it wouldn’t be worth buying that thing. I’m not sure how radical your viewpoint on this is. Would you go as far as to say that a hotel who has a guest that just stayed there for one night owns that hotel room? For how long do you have to use something for you to think that the user of that thing owns that thing. — TheHedoMinimalist

I actually don’t agree completely with the use-is-ownership principle for reasons similar to your questions (how long do I have to be away from home before it stops being my home? a decade? a day? a year? an hour? why that long exactly?). But I do think that there are other changes to how we construct our property rights that ought to be made both for deontological reasons and because of good consequences, one of which is discouraging scenarios where one person owns something that another person regularly uses, for the profit of the former at the expense of the latter, i.e. rent. Something approximating rent is still possible to construct under my scheme, so long as that’s actually what everyone involved actually wants, like a hotel room of whatever. Going into the full details on this would be a huge derailment of this thread though. -

Combining rationalism & empiricismyou mentioned Analytic vs Continental instead, but even that is already getting pretty dated...

in your opinion, is that train of though fading and if so which direction is it heading? — EnsambleMark

The clash between Analytic and Continental philosophy seems to be fading, as more contemporary philosophers try to draw from both strands and work on some synthesis of them. There isn’t a clear consensus on a singular new way forward, but I think that’s going to be in the direction of Pragmatism. -

Combining rationalism & empiricismis there a combined theory that unites rationalism and empiricism? — EnsambleMark

Maybe you'd like Kant? — norm

:100:

The conflict between "Rationalists" and "Empiricists" is pretty much only a Modern era (i.e. pre-Kantian) historical thing that doesn't really exist anymore. The contemporary parallel of it would be more like Analytic vs Continental instead, but even that is already getting pretty dated. -

TaxesFor example, it seems that the government can be justified in using physical violence to help a landlord evict her tenant that refuses to leave her property. — TheHedoMinimalist

Maybe it seems that way to you, but plenty of others would contest that that is removing the tenant from their rightful property at the behest of an unjust claim over it by another, because use justifies ownership. -

Life is getting easier with less money.If you have housing already taken care of, life is earlier with less money these days.

But affording housing is getting more and more impossible over time.

All of the "cherries on top" are super affordable now compared to a generation or two ago, so to those who already have their staple needs met, it looks like high times are cheap now.

But it's increasingly difficult to get those staples met -- to just own a place to sit and starve to death in the cold if you wanted, without being kicked out because you didn't pay thousands of dollars to someone who treats your shelter as their "investment". -

Religions : education :: states : governance -- a missing subfield of philosophy?Y'know maybe rather than starting new threads for each subtopic, I'll just do a series of posts in this thread.

As should already be clear from my earlier thread on epistemology, I am broadly against the validity of any supposed epistemic authority, and so against the epistemic legitimacy of any religion, where that term is understood to mean some institute that claims such authority. This position is generally called freethought. But such freethought does not mean that I am against all or necessarily any of the descriptive claims issued forth by such institutions, only that I am against them being taken as authoritative simply for being issued by such institutions.

Just because I am against any such institution being taken as epistemically authoritative does not mean that I am against all social institutions seeking to promote knowledge. I am very much in favor of a widespread, global collaborative process of many individuals sharing their insights into the nature of reality, checking each other's findings, and collating the resulting consensus together into the closest thing to an authoritative understanding of reality that it is possible to create, for the reference of others who have not undertaken such exhaustive research themselves.

The proviso is simply that that resulting product should always be understood to be a work in progress, always open to question and revision, though it should in time become more and more hardened such that questions to which it does not already have answers become more and more difficult to find, and so large revisions to it become more and more difficult to make. This is essentially the process of peer review already widely in use in contemporary academia, and I don't claim to be putting forth much if anything new here in that regard, merely documenting the structure of a process of which I approve, for completeness of my philosophy.

The process proceeds in three broad phases:

- In the first phase, in what are called primary sources of knowledge, researchers publish detailed accounts of the observations that they have made, including especially the circumstances under which they were made, such as the setup of an experiment if a controlled experiment was done, or other important contextual information if an observation was made in the field, so that others can later attempt to replicate those circumstances and see if they observe the same phenomena; and these primary sources can also share the conclusions their authors draw from their observations.

- In the second phase, in what are called secondary sources, groups of other researchers review and comment on the quality of that original research in media such as journals, republishing the original research that they find worthy in the process.

- In the third phase, still others gauge the consensus opinion held between those secondary sources on what can somewhat reliably, though of course always still tentatively, be said about what is real, and publish those conclusions in more accessible summary works called tertiary sources, such as textbooks and encyclopedias.

(@jgill I gather you work in academia yourself so maybe you can check this for accuracy.)

These reference works are thus the closest things to epistemically authoritative texts that are possible, the reasonable substitute for authoritative religious texts traditionally taken as infallible fonts of knowledge; though these tertiary sources are not to be taken so infallibly, but understood as merely the best findings about reality that are as yet available, the theories that have survived not only the empirical testing of some individual researcher, but also the heavy criticism of everyone else participating in this endeavor throughout the world. -

TaxesAlso, I don’t see how taxation couldn’t appropriately be understood as just like the rent that an individual has to pay to a civilized society to live in that civilized society. — TheHedoMinimalist

Rent is theft too, so this doesn’t resolve the problem. -

TaxesThe state taking money under threat of force from private individuals for its own benefit is clearly theft, unless you want to argue that the state really rightfully owns everyone and everything.

But a lot of private individuals acquire money unjustly from other private individuals, even if that acquisition is legally sanctioned. That's basically the definition of capitalism. And taking something back from a thief to compensate the victim is not another case of theft. So in a sense taking from the rich and powerful to care for the poor and powerless is, or at least can be, not theft.

However the way we (anywhere that has tax-funded welfare, not any particular country) do things now, we're not directly taking the ill-gotten gains specifically from the wrongdoers and giving it specifically back to the victims, but rather taking from the class of people reckoned to be likely wrongdoers with likely ill-gotten gains (or at least the subset of those who can't manage to weasel out of it), and giving to the class of people reckoned to be likely victims (or at least the subset of them who can manage to get in on that).

Basically, we're trying to fight theft with theft. Which... is better than just letting the theft go unabated in one direction but not the other. But it's obviously still not perfect. Far better to just stop the original theft, or at least, tax specifically the problematic kinds of gains, to fund welfare specifically to the people victimized in the process.

Like say, tax net income from rent and interest, and if that is a negative number (because someone's paying more rent and interest than they get), then that tax becomes negative, and so a form of cash welfare. -

Religions : education :: states : governance -- a missing subfield of philosophy?It's not always been the case that government was separated into those three branches, but it's argued that there are good reasons why they should. I'm not saying that people in academia usually are separated along those lines, but that there may be analogous reasons that they should be: that one person should not both write the textbook, and teach from it, and test the students on whether they know their stuff. But, arguing for or against that is going to be a topic of one of those later threads I mentioned.

-

How small can you go?The Planck length may also represent the diameter of the smallest possible black hole. — T Clark

I have wondered about this relationship before, and how if (the big "if" in question in this thread) elementary particles actually are infinitesimal points, they would necessarily be black holes (the density of any point with nonzero mass is infinite, and so well above the threshold to form a black hole), and the smallest possible one would have a Schwarzchild radius of the Planck length. Since we don't even know if normal stellar-mass black holes contain actual singularities and suspect that they do not, it's probably not even necessary that fundamental particles be actual literal point particles, for us to consider them effectively tiny black holes. -

What got you into this?I had always had very broad intellectual interests, but was always searching for ever more and more fundamental principles underlying all of those interests. So over my teens I increasingly focused my natural science interests toward physics, and my social science interests toward something in the direction of economics or political science.

Digging deeper into each of those, I eventually realized that my interests were essentially in what I now recognize as roughly metaphysics and ethics. When I discovered professional philosophy and realized that those two things were, broadly speaking, what the field was all about, I thought that that field was the place where I would find what I was looking for.

So that’s what I eventually got my BA in.

“The point of philosophy is to start with something so simple as not to seem worth stating, and to end with something so paradoxical that no one will believe it.”

-Bertrand Russell — khaled

That is an excellent quote that I heard once long ago and then forgot exactly what it was and who said it. I think I’m going to have to quote that in my book, right after the part where I say:

“The general worldview I am going to lay out is one that seems to me a naively uncontroversial, common-sense kind of view, i.e. the kind of view that I expect people who have given no thought at all to philosophical questions to find trivial and obvious. Nevertheless I expect most readers, of most points of view, to largely disagree with the consequent details of it, until I explain why they are entailed by that common-sense view.” -

Linguistic prescriptivism? Or analytic a posteriori knowledge?Ah I see the issue now. Fixed in OP. Thanks!

-

Linguistic prescriptivism? Or analytic a posteriori knowledge?Like if "Superman" and "Clark Kent" are just two names for the same person, then everything that is true of Superman is necessarily also true of Clark Kent, because there's only one person in question.

Or in Kripke's paradigmatic example, that "water" and "H2O" are two names for the same substance. Everything that's true of water is also true of H2O, because there's not two kinds of stuff, just two names for one kind of stuff. -

Atheism is delusional?I feel the only way to escape this paradox is to say that we are designed by some higher truth in the universe. — Franz Liszt

If we don't even know whether or not we can know anything, we nevertheless cannot help but act as though we believed one way or the other (either that we can gain knowledge, or not), by either trying to figure things out, or not. To not try would guarantee that we will not figure things out, so if we want to figure things out if it should be possible, but we don't know whether or not it's possible, the best bet is to try, rather than just to give up out the gate.

But there are two different kinds of "giving up out the gate": one is to assume that knowledge is impossible, but the other is to assume that it is guaranteed. The first is to assume that there are questions that cannot be answered; the latter is to assume that there are answers that must not be questioned.

So if you're starting from a place of such uncertainty that you're not even certain about uncertainty, the practical solution is to start by avoiding the assumptions of either unquestionable answer or unanswerable questions, and try to figure out to the best of your ability what is more or less true, keeping in mind always that any answer might be wrong, but that that doesn't mean that every answer has to be wrong[/i].

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum