-

Marx's Value TheoryThe two earlier forms (A,B) either express the value of each commodity in terms of a single commodity of a different kind ( A ), or in a series of many such commodities (B) . In both cases, it is, so to say, the special business of each single commodity to find an expression for its value, and this it does without the help of the others. These others, with respect to the former, play the passive parts of equivalents.

The passivity ascribed to commodities in forms A and B is a reference to their status as networks of 'accidental' exchange, commodities are traded for each other when they are worth each other, but this worth does not have a universal standard; the value forms A and B are 'deficient in unity' because...

The general form of value, C, results from the joint action of the whole world of commodities, and from that alone. A commodity can acquire a general expression of its value only by all other commodities, simultaneously with it, expressing their values in the same equivalent; and every new commodity must follow suit. It thus becomes evident that since the existence of commodities as values is purely social, this social existence can be expressed by the totality of their social relations alone, and consequently that the form of their value must be a socially recognised form.

the valuations they consist of do not form an integrated system of exchange or of a notion of value ascription which applies over all such trades. Moreover, they generally will have the form of barter - any good for any good in A, or any good for an important good in B - as contrasted to C. In C, all commodities express their value in a single commodity; and the logic works for any commodity. Which is to say that the notion of value in C forces every commodity to express the value of every other commodity relative to it; any can be elected as a universal equivalent. The ascription of a universal equivalent (linen in Marx's example, a in my mathematical note) is the distinguishing characteristic of the general form C, but it is not solely a conceptual ascription, the way value works economically must be consistent with C and reproduce it. Which is to say, all commodities must have value in a univocal sense and this sense must be expressed as the value of any commodity, and that understanding of value should be carried forth by the social circumstances embodying it.

All commodities being equated to linen now appear not only as qualitatively equal as values generally, but also as values whose magnitudes are capable of comparison. By expressing the magnitudes of their values in one and the same material, the linen, those magnitudes are also compared with each other. For instance, 10 lbs of tea = 20 yards of linen, and 40 lbs of coffee = 20 yards of linen. Therefore, 10 lbs of tea = 40 lbs of coffee. In other words, there is contained in 1 lb of coffee only one-fourth as much substance of value – labour – as is contained in 1 lb of tea.

This section diagnoses the transitivity of 'is worth' as an essential constituent of the value form, roughly why this is required is because it allows the formation of a universal equivalent and the equivalence classes of value that equivalent represents in a definite quantity. It is at this point that the social relationships between the commodities which affix their exchange ratios are given summary through and embodied fully in each and every commodity. If this is reminiscent of commodity fetishism - in which the social relations between people appear as material relations of things -, it should.

The general form of relative value, embracing the whole world of commodities, converts the single commodity that is excluded from the rest, and made to play the part of equivalent – here the linen – into the universal equivalent. The bodily form of the linen is now the form assumed in common by the values of all commodities; it therefore becomes directly exchangeable with all and every of them. The substance linen becomes the visible incarnation, the social chrysalis state of every kind of human labour. Weaving, which is the labour of certain private individuals producing a particular article, linen, acquires in consequence a social character, the character of equality with all other kinds of labour. The innumerable equations of which the general form of value is composed, equate in turn the labour embodied in the linen to that embodied in every other commodity, and they thus convert weaving into the general form of manifestation of undifferentiated human labour. In this manner the labour realised in the values of commodities is presented not only under its negative aspect, under which abstraction is made from every concrete form and useful property of actual work, but its own positive nature is made to reveal itself expressly. The general value form is the reduction of all kinds of actual labour to their common character of being human labour generally, of being the expenditure of human labour power.

Another argument from structural symmetry (see here for summary diagram), since every commodity manifests in a universal equivalent, the concrete labours in each only matter in terms of the abstract labour they embody. Marx sees forms A, B and C as developments of intensity of the dominance of abstract over concrete labour (of value over utility as determinants of economic worth), and C is the first structure which exhibits the total dominance of value over utility.

This perspective dominates the social function and perception of labour when form C is operative.

'Do you like your job?'

'No.'

'Why do you keep doing it?'

'It pays the bills'

As Marx puts it:

The general value form, which represents all products of labour as mere congelations of undifferentiated human labour, shows by its very structure that it is the social resumé of the world of commodities. That form consequently makes it indisputably evident that in the world of commodities the character possessed by all labour of being human labour constitutes its specific social character.

The social function of labour becomes equated with its value creative component. -

The Hyper-inflation of Outrage and Victimhood.It's very difficult to disagree with the OP due to how it's framed. Everyone will agree that inappropriate emphasis should not be given to inappropriate outrage, and everyone will agree that appropriate emphasis should be given to appropriate outrage. As eloquently as you've defended your position @VagabondSpectre, it boils down to the selective use of a tautology as a cudgel - or as an inert lamentation. Something like a political Barnum statement, people will fill up the OP with examples which are great for them; everyone can agree entirely within their own selection criterion; which ultimately reflects their personal preferences and ideological standpoint.

To be sure, attention is currency in the marketplace of ideas; which boils down to social media in terms of exposure nowadays; and things which garner attention garner more attention. I made a thread a couple of months ago on a similar topic, though I did not intend to be as even handed as you did throughout. Specifically I was looking at where some pretty crap terms in our political discourse came from and how easily memed ideas interact with the attention economy to produce an overall lack of nuance. But also how this lack of nuance has been coopted (sometimes explicitly as with a few of the terms I mentioned in that thread) by interest groups on the far right.

I imagine what we can all agree on is that legitimate causes for consciousness raising are served very well by the current attention economy, but purely incidentally. Even if that consciousness raising yields little social transformation, some of the time it is worth all the spittle and spilled ink. Hashtag metoo and yesallwomen come to mind for, at the very least, trying to make people think about whether consent has been established for sexual advances. Say what you will about people who over simplified consent establishment in those beautifully progressive little outrages, and I might even agree with you. Regardless, it got women speaking out about their all too frequent sexual harassment which we've known about for quite a while from the statistics.

So yeah, as much as social media can be little more than a vector for invective, they're a universal message amplifier by design. If we're apportioning blame to Twitter for normalising outrage about Donald Trump's sexual misconduct, I'd put a hefty chunk of the blame on the way the algorithms work. Hashtag Trump aggregates all the nuances into an already dismissible narrative (FAKE NEWS, like what our OPs brand inappropriate outrage), and longer messages (what, 250 characters is long?) are harder to hear at the same time as their echoes. -

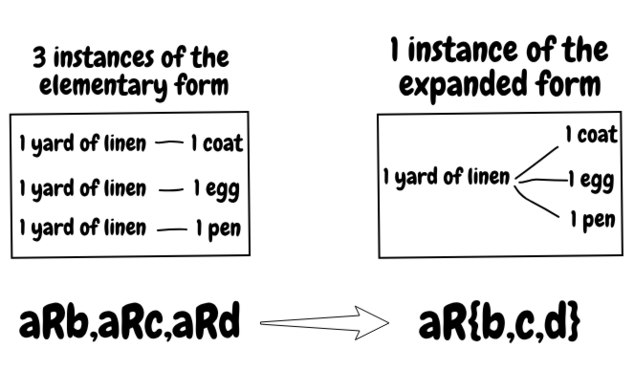

Marx's Value TheoryGoing through the section more meticulously now, this expands on the exegesis for the Marx's solution to the deficiency in the expanded form and that forms' modification to the general form A,B,C denote the forms of value pictured above. A is elementary, B is expanded with deficiency, C is expanded with the deficiency removed; general.

Considering C as compared to A and B:

All commodities now express their value (1) in an elementary form, because in a single commodity; (2) with unity, because in one and the same commodity. This form of value is elementary and the same for all, therefore general.

The recipe to move from the deficient expanded form to the general form is to place a restriction on the 'is worth' relation T. A restriction of a relation confines that relation to when defined properties hold of its inputs. EG, if we have the relation 'x is taller than y' on the set of all humans, we can restrict that relation to children and obtain an ordering on children's heights rather than children and adults. Formally what this looks like is:

where T is the 'is worth' relation and P(x,y) is some property of either x or y or both. In the case pictured above, the relation T looks like this for the deficient form (with the notionally equal values and reflexives thrown in):

had to change to () and split it up because {} breaks with longer equations for some reason. The restriction of the deficient form to only those pairs which have a in the place on the right yields:

which defines a function on {a,b,c,d} to {a} such that every element besides a is mapped onto a. This function supplies the conditions (1) and (2) - only one entity occupies the position of equivalent ( a )

and it is the only member of its set (unity). Also the plurality of elements in the relative form is annihilated in terms of their value because T holds between them all. Another way to think of this is that what we are doing is picking a single element, a, out of the equivalence relation, T, finding a's equivalence class [a] (all elements related to a), then mapping all the elements in [a] besides a to a.

Excluding (a,a) from T is almost the same as choosing a representative of the equivalence class as discussed before, if we also map a to a then this really is choosing a representative. a 'avoids' this map because for Marx aTa never holds, but since including it is harmless (as argued before), we can map a to a and obtain a substantial theoretical insight and simplification. The value of a commodity is equal to the value of any of its equivalents.

Because equivalence relations partition the set of commodities, this renders the value unique for any commodity and a single commodity (even the same one for each class, which will appear in varying amounts for each class) can be chosen as the representative for each equivalence class. So 'a' could be chosen for all of them.

So the restriction onto 'targeting a' is better thought of as choosing a representative for the equivalence class. Note that completing the relation by applying symmetry, transitivity and reflexivity to T|a yields T again - the deficient form never 'went away' and the equivalence classes use it to express value determinately - as desired.

For the sake of explicitness, choosing a as the representative of the equivalence class (a,b,c,d) is this mapping F=(a->a,b->a,c->a,d->a). Restricting T to a (forming T|a) without including the pair (a,a) in T (excluding reflexives) gives G=(b->a,c->a,d->a). It's obvious that if we include a in the set G works on we end up with F; choosing a as the representative.

The forms A and B were fit only to express the value of a commodity as something distinct from its use value or material form.

The first form, A, furnishes such equations as the following: – 1 coat = 20 yards of linen, 10 lbs of tea = ½ a ton of iron. The value of the coat is equated to linen, that of the tea to iron. But to be equated to linen, and again to iron, is to be as different as are linen and iron. This form, it is plain, occurs practically only in the first beginning, when the products of labour are converted into commodities by accidental and occasional exchanges.

From the perspective of the elementary form A, we can imagine an isolated series of trade relations each saying x is worth y and y is worth x. Following the myth of barter, this tracks 'accidental' exchanges before the transformation of an economy into commodity production. The elementary form of value, as frank pointed out earlier (and I pointed out in an opening post) doesn't actually reflect the form of value in a capitalist economy (too little structure for its general function). If trades remain isolated and goods are not produced primarily for exchange , considerations of relative utility rather than relative value will be the norm.

The second form, B, distinguishes, in a more adequate manner than the first, the value of a commodity from its use value, for the value of the coat is there placed in contrast under all possible shapes with the bodily form of the coat; it is equated to linen, to iron, to tea, in short, to everything else, only not to itself, the coat. On the other hand, any general expression of value common to all is directly excluded; for, in the equation of value of each commodity, all other commodities now appear only under the form of equivalents. The expanded form of value comes into actual existence for the first time so soon as a particular product of labour, such as cattle, is no longer exceptionally, but habitually, exchanged for various other commodities.

Form B is adopted when a trade network expands and begins to centralise around a set of privileged goods. Value obtains no unitary and substrate-independent expression in this form (recall the notes on the indeterminacy of the expanded form), rather goods obtain their values through what they may be traded for normally. It consists of coupled and inter-related elementary forms with several centralising commodities; like cattle, shells, patches of cloth for real world examples. Comparisons of utility may still drive exchanges somewhat, but this form of value is the first time that a mercantile, 'get more stuff' perspective can be adopted towards the entire network of goods. Amassing wealth in this form is still associated with amassing use values rather than exchange value (due to the indeterminacy of the expression of value).

The third and lastly developed form expresses the values of the whole world of commodities in terms of a single commodity set apart for the purpose, namely, the linen, and thus represents to us their values by means of their equality with linen. The value of every commodity is now, by being equated to linen, not only differentiated from its own use value, but from all other use values generally, and is, by that very fact, expressed as that which is common to all commodities. By this form, commodities are, for the first time, effectively brought into relation with one another as values, or made to appear as exchange values.

Form C, the general form, requires that the entire trade network is able to be relativised to the production of one good (restricting T to a in my example, restricting to linen in Marx's), but the logic works for any good to obtain its value in a definite amount. The social norms surrounding trade centralise around the trade of a particular good for goods in general and goods in general in a definite amount have their measure in an amount of that particular good. This produces a substrate independent character to value; it no longer needs to relate to anything but the mere presence of utility (bearing a use value, being the product of social labour); and the properties of the value of commodities become aligned with the statistical properties of their production processes; of human labour in the abstract. -

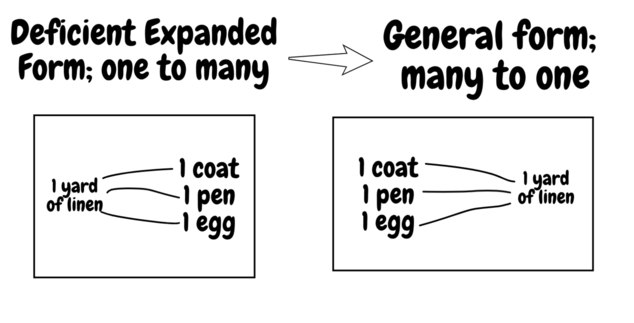

Marx's Value TheorySo one puzzle here is that the general form of value (depicted on the right above) is consistent with the deficient expanded form of value (on the left above); the first and the second are dual notions. This is scouting ahead a bit, but it's worthwhile showing exactly why transitivity is an important component of the value form.

What this means precisely is that if we have aRb, aRc, aRd, where a is the yard of linen, b the coat, c the pen and e the egg, then we also have bRa , cRa and dRa in the value form when conceived as the relation T on the set of commodities - again, this is because the relation is symmetric. If the two notions are dual; like 'less than or equal to' and 'greater than or equal to'; how can one be deficient and the other not when one is just the transposition of the other?

Marx summarises the deficiency as follows:

The (Any specific equivalent), indeed, gains adequate manifestation in the totality of its manifold, particular, concrete forms. But, in that case, its expression in an infinite series is ever incomplete and deficient in unity.

And summarises why transposing the deficient to the general form solves the problem:

All commodities now express their value (1) in an elementary form, because in a single commodity; (2) with unity, because in one and the same commodity. This form of value is elementary and the same for all, therefore general.

Mathematically then, removing the deficiencies of the expanded form has to place a single commodity as an equivalent for the infinite series of commodities; that commodity's relative value is then expressed through the commodities in that chain. Moreover, the commodities in that chain should present a single magnitude of value. As Marx puts it:

All commodities being equated to linen now appear not only as qualitatively equal as values generally, but also as values whose magnitudes are capable of comparison. By expressing the magnitudes of their values in one and the same material, the linen, those magnitudes are also compared with each other. For instance, 10 lbs of tea = 20 yards of linen, and 40 lbs of coffee = 20 yards of linen. Therefore, 10 lbs of tea = 40 lbs of coffee. In other words, there is contained in 1 lb of coffee only one-fourth as much substance of value – labour – as is contained in 1 lb of tea

Here is the first explicit mention of the transitivity of T. 10 tea = 20 linen, 20 linen = 40 coffee, 10 tea = 40 coffee. So the 'deficiency in unity' of the relative form is solved by requiring the transitivity of T; which means that T is now reflexive, symmetric and transitive. An equivalence relation - like equality of numbers. This partitions the set of commodities into subsets of equal worth.

However, the raw equivalence relation itself is still applicable to the expanded form of value with its deficiencies intact. If we wanted to look at the expanded form in general and obtain the value of say 1 yard of linen, how could we do this? We need to avoid this many-to-one relationship when trying to value 1 yard of linen, otherwise its expression is 'deficient in unity'.

Which is to say, if we want to obtain the value of 1 yard of linen, we should take only the elements of T which have 1 yard of linen in the right position; collecting all x for which 'x is worth 1 yard of linen'. If we do this in my example with pens, eggs and coats, this gives the set {1 pen, 1 egg, 1 coat, (1 yard of linen, but ignore this}} mapping to {1 yard of linen}. Can we conclude from this set up that 1 pen, 1 egg and 1 coat are of equivalent value?

We have that 1 pen is worth 1 yard of linen, but also that 1 yard of linen is worth 1 egg. Therefore 1 pen is worth 1 egg. What this entails is 'chasing arrows' along the diagram, if there is a path between a commodity and another commodity then they are worth the same. This means that all {1 pen, 1 egg, 1 coat} are all connected through 1 yard of linen, and so are worth the same. We also have that for all commodities xTy and yTz imply xTz (argument for this is simple; link all commodities through their equivalent, the whole thing is a 'chain of equations' 1 pen <-> 1 egg <-> 1 coat <-> 1 pen, and this is what a transitive relation looks like). So when T is restricted in the manner: {x in C such that xT(1 yard of linen) }, it becomes a surjective function from C to {1 yard of linen} (avoiding many to one) and everything in that set is of equivalent worth. -

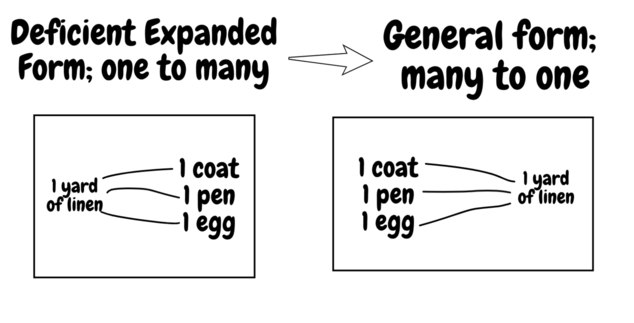

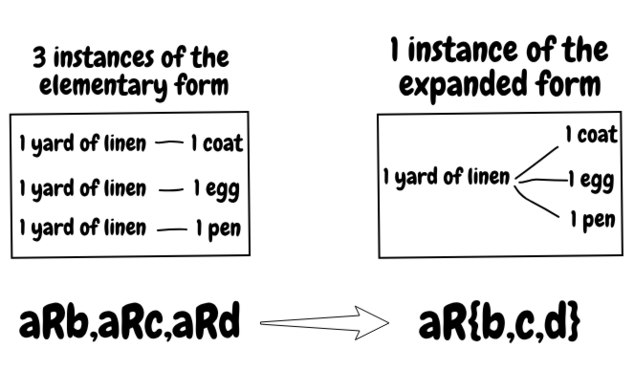

Marx's Value TheoryMarx proceeds to 'fix' these problems (lack of unity, indeterminate expression) in the expanded form.

First exploiting the symmetry condition of the 'is worth' relation:

The expanded relative value form is, however, nothing but the sum of the elementary relative expressions or equations of the first kind, such as:

20 yards of linen = 1 coat

20 yards of linen = 10 lbs of tea, etc.

Each of these implies the corresponding inverted equation,

1 coat = 20 yards of linen

10 lbs of tea = 20 yards of linen, etc.

In fact, when a person exchanges his linen for many other commodities, and thus expresses its value in a series of other commodities, it necessarily follows, that the various owners of the latter exchange them for the linen, and consequently express the value of their various commodities in one and the same third commodity, the linen. If then, we reverse the series, 20 yards of linen = 1 coat or = 10 lbs of tea, etc., that is to say, if we give expression to the converse relation already implied in the series, we get.

(my drawing rather than Marx's)

This gives valuation the structure of a surjective function on the set of commodities; a set of commodities of equivalent value is mapped to a specific amount of one commodity which serves as the equivalent. -

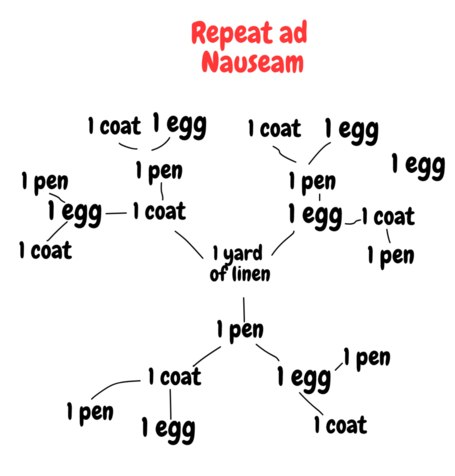

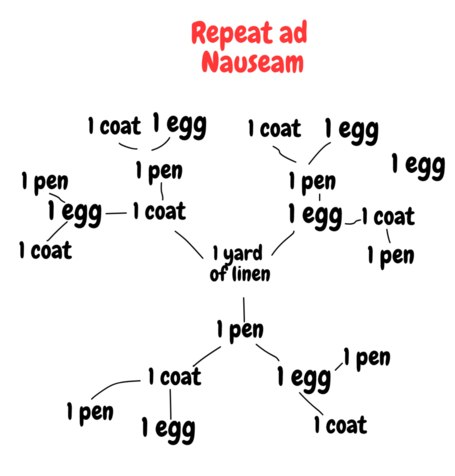

Marx's Value TheoryThe above diagram represents what I believe is the intuition behind Marx's diagnosis of 'defects' in the expanded form of value developed thus far. Marx begins his analysis of these defects as follows:

In the first place, the relative expression of value is incomplete because the series representing it is interminable. The chain of which each equation of value is a link, is liable at any moment to be lengthened by each new kind of commodity that comes into existence and furnishes the material for a fresh expression of value.

Imagine that we start from a commodity, pictured above as 1 yard of linen, and we have its set of equivalents: 1 egg, 1 pen, 1 coat. The only way we can express the value of 1 yard of linen is to put it in the relative form with respect to some equivalent; but we have 1 egg, 1 pen and 1 coat as the set of equivalents. We wish to obtain a determinate expression for the value of 1 yard of linen, and must thus appeal to an equivalent for it. However, as soon as we obtain an equivalent for it (either 1 egg, 1 pen or 1 coat), that commodity's relative value is expressed through its own 'is worth' relations; and is substitutable for all the commodities for which it has equivalent worth. We can keep substituting like this and end up with this expanding graph emanating from 1 yard of linen as its source.

To be sure, each 'x is worth y' does indeed express the value of x in terms of y, but the value of y must also be expressed in terms of one of its equivalents to make sense of the idea that the equivalent is now a set of commodities rather than any specific one. Universal commensurability was obtained in the value form at the price of the indeterminacy of each instance of the 'is worth' relation; whose destruction manifests as a one to many relationship between the relative and equivalent forms. This renders indeterminate the expression of relative values with precisely the same mechanism as it renders commensurable a commodity with every other. Marx continues:

In the second place, it is a many-coloured mosaic of disparate and independent expressions of value. And lastly, if, as must be the case, the relative value of each commodity in turn, becomes expressed in this expanded form, we get for each of them a relative value form, different in every case, and consisting of an interminable series of expressions of value.

and highlights a second deficiency of the expanded form analysed so far. The diagram above shows what happens when you try to obtain the value of a commodity through an equivalent solely with reference to the expanded form; a ceaseless chain of substitutable elements. Such a chain is not guaranteed to be the same for every commodity; indeed if we took half a yard of linen the quantities of commodities it is exchanged for differ and produce different nodes on the graph. This means that the relative form is not consistent over commodities despite portraying the same essential relationship of value equivalence.

The defects of the expanded relative value form are reflected in the corresponding equivalent form. Since the bodily form of each single commodity is one particular equivalent form amongst numberless others, we have, on the whole, nothing but fragmentary equivalent forms, each excluding the others. In the same way, also, the special, concrete, useful kind of labour embodied in each particular equivalent, is presented only as a particular kind of labour, and therefore not as an exhaustive representative of human labour generally. The latter, indeed, gains adequate manifestation in the totality of its manifold, particular, concrete forms. But, in that case, its expression in an infinite series is ever incomplete and deficient in unity.

'Each excluding the others' references that once a definite quantity of a commodity is selected, the above diagram would have all of its nodes relabelled; the set of all commodities becomes relativised to a particular commodity, despite that 'x is worth y' should be a statement of equivalent worth in the same sense. The 'sense' of 'x is worth y' in the deficient expanded form is given by these ceaselessly expanding graphs, unique in node labels for every originating commodity. -

Marx's Value TheoryThe loss of determinate expression of a commodity's value in the expanded form above is analysed in the next section.

3. Defects of the Total or Expanded form of value

but my brain has died now. More later. -

Marx's Value TheorySubsubsection: The Expanded Relative Form of Value

The major new feature of the expanded form of value over the elementary form of value is that value has become universal. This in the sense that a commodity stands as commensurable to all other commodities through exchange; with their exchange ratios determined with the same means as before.

The value of a single commodity, the linen, for example, is now expressed in terms of numberless other elements of the world of commodities.

This is the meaning of mapping the elementary forms above; aRb, aRc, aRd to their composite in the expanded form: aR{b,c,d}. This means that 'a is worth b, a is worth c and a is worth d' transforms to 'a is worth b or c or d', and thus the relative value of a is now expressed in terms of all other commodities which share its worth.

In terms of the previous algebraic structure of commodities, the nature of the 'is worth' relation has changed from 'x is worth y' being a disordered (yet symmetric) set of pairs to 'x is worth [y]', where [y] is the collection of all commodities which are substitutable in this expression. Insofar as all commodities in a definite quantity have the same value as x they serve together as the equivalent form of value for x. Marx expands on this point using the previously established structural symmetries relating expressions of value to social characteristics of labour.

Every other commodity now becomes a mirror of the linen’s value.[25] It is thus, that for the first time, this value shows itself in its true light as a congelation of undifferentiated human labour. For the labour that creates it, now stands expressly revealed, as labour that ranks equally with every other sort of human labour, no matter what its form, whether tailoring, ploughing, mining, &c., and no matter, therefore, whether it is realised in coats, corn, iron, or gold.

For Marx, the expanded form of value obviously displays the homogeneity of human labour in terms of its value creative aspects which was hidden in the analysis of the elementary form alone. The qualitative particularity of commodities in terms of their useful physical characteristics (use values) and the acts of labour which imbue the commodity with those characteristics is completely suppressed in the expanded form; this is because the expanded form relates any quantity of a use value to some quantity of every other use value. Value becomes untethered from the elementary form to the extent that the elementary form completely iterates through the set of all commodities and maps pairs of commodities to their exchange ratios. As Marx puts it:

The linen, by virtue of the form of its value, now stands in a social relation, no longer with only one other kind of commodity, but with the whole world of commodities. As a commodity, it is a citizen of that world. At the same time, the interminable series of value equations implies, that as regards the value of a commodity, it is a matter of indifference under what particular form, or kind, of use value it appears.

The iteration of the elementary form of value through the set of commodities destroys the privilege of y in the 'x is worth y' relation; the form of manifestation of x's value is no longer a definite quantity of a fixed use value, it is of a set of all use values in quantities that render them equivalent to x. Marx expands on this point:

In the first form, 20 yds of linen = 1 coat, it might, for ought that otherwise appears, be pure accident, that these two commodities are exchangeable in definite quantities. In the second form, on the contrary, we perceive at once the background that determines, and is essentially different from, this accidental appearance. The value of the linen remains unaltered in magnitude, whether expressed in coats, coffee, or iron, or in numberless different commodities, the property of as many different owners. The accidental relation between two individual commodity-owners disappears.

The 'background' marks refers to is the commensurability of all commodities with each other; that they can all serve as the equivalent for any other in some determinate quantity. Marx points out a category error which this highlights; when we consider two goods with equivalent worth in capitalist regimes of production, what is special about 'x is worth y' as an expression of value for x? Nothing at all; this means that it would be impossible to determine the values for x and for y in terms of 'x is worth y' in the absence of this universal medium of exchange. Just as 'x is worth x' was a meaningless tautology before, 'x is worth y' loses its specific meaning as the expression of x's value because x's value distributes over the entire set of commodities. Concrete acts of exchange, incidents of the relation 'x is worth y', lose their capacity to determinately express x's value even though they still express x's value as a mere instance of the expanded form. Thus Marx points out:

It becomes plain, that it is not the exchange of commodities which regulates the magnitude of their value; but, on the contrary, that it is the magnitude of their value which controls their exchange proportions.

2. The particular Equivalent form

Marx exploits the structural symmetry between use/exchange values and concrete/abstract labour to chart the transformation of labour under the expanded form:

Each commodity, such as, coat, tea, corn, iron, &c., figures in the expression of value of the linen, as an equivalent, and, consequently, as a thing that is value. The bodily form of each of these commodities figures now as a particular equivalent form, one out of many. In the same way the manifold concrete useful kinds of labour, embodied in these different commodities, rank now as so many different forms of the realisation, or manifestation, of undifferentiated human labour.

The iteration of 'x is worth y' through the set of commodities also conditions the concrete instances of labour which produce x and y; y is now an arbitrary placeholder which represents the set of quantities of commodities which can serve as an equivalent to x. The universalisation of value over the commodities maps the functioning of the value form explicitly to all of its quantitative exchange relations; and insofar as it does this, human labour embodied in each commodity is equated to human labour embodied in any other; yielding the sum total of productive labour as an amorphous goop (of abstract labour) as far as the value form is concerned. -

Marx's Value TheoryDiagram of the expanded form of value. Lines between commodities denote instances of 'x is worth y'.

-

Marx's Value TheorySubsection 4: The Elementary Form of Value considered as a whole.

This section is mostly a summary of the Relative Form and Equivalent Form sections, and it sets up the analysis of the expanded form in the next section.

The first three paragraphs are recaps.

The elementary form of value of a commodity is contained in the equation, expressing its value relation to another commodity of a different kind, or in its exchange relation to the same. The value of commodity A, is qualitatively expressed, by the fact that commodity B is directly exchangeable with it. Its value is quantitatively expressed by the fact, that a definite quantity of B is exchangeable with a definite quantity of A. In other words, the value of a commodity obtains independent and definite expression, by taking the form of exchange value. When, at the beginning of this chapter, we said, in common parlance, that a commodity is both a use value and an exchange value, we were, accurately speaking, wrong. A commodity is a use value or object of utility, and a value. It manifests itself as this two-fold thing, that it is, as soon as its value assumes an independent form – viz., the form of exchange value. It never assumes this form when isolated, but only when placed in a value or exchange relation with another commodity of a different kind. When once we know this, such a mode of expression does no harm; it simply serves as an abbreviation.

Commodities are a composite of use and exchange value. The use value of the commodity is what it may be used for, the exchange value is what it may be exchanged for. Use and exchange are not on equal footing metaphysically, the use value follows from the physical properties imbued into the commodity during its acts of production; use value is product of concrete labour. Exchange value, however, follows from the social structure of exchange; specifically how much labour was expended in the production of the commodity. However, it is not the case that the value of a commodity is branded upon it by the specific duration of the concrete labour which produced it, rather the expenditure of human labour power in its production is socially mediated through the general social conditions for that commodity's production. In this manner, the exchange value arises from the statistical properties of the social processes of its production, not from the physical properties of the commodity. Furthermore, a commodity can only be said to have an exchange value when it is treated under the aspect of exchange; equated to others notionally or treated as equivalents in exchange.

Our analysis has shown, that the form or expression of the value of a commodity originates in the nature of value, and not that value and its magnitude originate in the mode of their expression as exchange value. This, however, is the delusion as well of the mercantilists and their recent revivers, Ferrier, Ganilh,[23] and others, as also of their antipodes, the modern bagmen of Free-trade, such as Bastiat. The mercantilists lay special stress on the qualitative aspect of the expression of value, and consequently on the equivalent form of commodities, which attains its full perfection in money. The modern hawkers of Free-trade, who must get rid of their article at any price, on the other hand, lay most stress on the quantitative aspect of the relative form of value. For them there consequently exists neither value, nor magnitude of value, anywhere except in its expression by means of the exchange relation of commodities, that is, in the daily list of prices current. Macleod, who has taken upon himself to dress up the confused ideas of Lombard Street in the most learned finery, is a successful cross between the superstitious mercantilists, and the enlightened Free-trade bagmen.

Marx stresses that the analysis of the form of value logically precedes concrete acts of exchange; he sees the form of value both as a condition of possibility for exchange and valuation to function as is in the sphere of capitalist production; and he sees it as a real component of what occurs to the commodity in terms of its value when it is subject to exchange. In this regard, we can view the analysis of the value form so far as (the beginnings of) a semantics of 'x is worth y' in capitalist production and exchange. The account of the meaning of 'x is worth y' consists in what it means for x to be in the first slot in the phrase; for it to be in the relative form; and for y to be in the second slot in the phrase; for y to be in the equivalent form. Marx summarises his developments on this topic:

A close scrutiny of the expression of the value of A in terms of B, contained in the equation expressing the value relation of A to B, has shown us that, within that relation, the bodily form of A figures only as a use value, the bodily form of B only as the form or aspect of value. The opposition or contrast existing internally in each commodity between use value and value, is, therefore, made evident externally by two commodities being placed in such relation to each other, that the commodity whose value it is sought to express, figures directly as a mere use value, while the commodity in which that value is to be expressed, figures directly as mere exchange value. Hence the elementary form of value of a commodity is the elementary form in which the contrast contained in that commodity, between use value and value, becomes apparent.

Every product of labour is, in all states of society, a use value; but it is only at a definite historical epoch in a society’s development that such a product becomes a commodity, viz., at the epoch when the labour spent on the production of a useful article becomes expressed as one of the objective qualities of that article, i.e., as its value. It therefore follows that the elementary value form is also the primitive form under which a product of labour appears historically as a commodity, and that the gradual transformation of such products into commodities, proceeds pari passu with the development of the value form.

'x is worth y' expresses the (exchange) value of x as a definite quantity of the use value of y. x counts as its exchange value while y counts as a definite quantity of use value. Therefore, a given amount of x is worth a given amount of y means the value of x is the given amount of y. Recognising that 'x is worth y' presents its constitutive social relations as a numerical equivalence, Marx notes that this also implies 'x is worth y'; the value form; is developed through history.

We perceive, at first sight, the deficiencies of the elementary form of value: it is a mere germ, which must undergo a series of metamorphoses before it can ripen into the price form.

The expression of the value of commodity A in terms of any other commodity B, merely distinguishes the value from the use value of A, and therefore places A merely in a relation of exchange with a single different commodity, B; but it is still far from expressing A’s qualitative equality, and quantitative proportionality, to all commodities. To the elementary relative value form of a commodity, there corresponds the single equivalent form of one other commodity. Thus, in the relative expression of value of the linen, the coat assumes the form of equivalent, or of being directly exchangeable, only in relation to a single commodity, the linen.

The elementary form of value is conceptually the simplest value form Marx analyses which is still relevant for capitalist production; the other forms of value make different uses of 'x is worth y' germinally, as its constitutive elements. When actually looking at commodities we can find that 'x is worth y' but also that 'x is worth z' and 'y is worth t', and all of these can be considered at once and co-occur as equivalent valuations. The elementary form of value provides a semantics solely for statements taking the form 'x is worth y' with no additional structure; no extra commodities or their exchange relations.

Nevertheless, the elementary form of value passes by an easy transition into a more complete form. It is true that by means of the elementary form, the value of a commodity A, becomes expressed in terms of one, and only one, other commodity. But that one may be a commodity of any kind, coat, iron, corn, or anything else. Therefore, according as A is placed in relation with one or the other, we get for one and the same commodity, different elementary expressions of value.[24] The number of such possible expressions is limited only by the number of the different kinds of commodities distinct from it. The isolated expression of A’s value, is therefore convertible into a series, prolonged to any length, of the different elementary expressions of that value.

Marx indicates that the next stage of his analysis of value will begin b making composites of 'x is worth y', of the form 'x is worth y', 'x is worth z' and so on. Having the relative value of x take on different commodities for its equivalent. Which leads us onto the next section, the expanded form of value. -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical Platonism

Since you've already primed me to think of this in terms of the creation of the synthetic a priori and how that creation interfaces conceptually with the world, it's interesting. Maybe my new mantra reading on similar topics should be: 'they're talking about how we interface with the world through language'. Your prose in the first note isn't making my eyes glaze, though, so thank you for that. -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical Platonism

I sometimes get the feeling that analytic philosophers hide that they're talking about anything interesting by talking about language. So my eyes often glaze over when they shouldn't. I will read your notes on them, though. -

My topic deleted! :(I deleted your topic because it was 1.5 lines consisting solely of an injunction for your readers to forget their pasts, assuming I haven't confused you with someone else. It's not philosophy and there's no effort. I suggest if you are so annoyed at losing visibility for your idea you post that injunction in the Shoutbox.

-

Marx's Value Theory

If you do have substantive criticisms, can you please quote my exegesis or Marx? I also want discussions here to be mostly textual rather than freeform; so problems in Marx's logic, inaccurate examples or deductions, conceptual errors that make him necessarily elide relevant topics, bits he's missed - that kind of thing.

I acknowledge that the account so far would be better grounded in up to date anthropology. Though I do not see any obvious problems for Marx's account so far that arise from lack of knowledge of up to date anthropology. The only site of tension I see is between the modality of the links in the value form argument; abstract labour and value magnitudes being expressions of socially necessary labour time are both derived through a conceptual necessity; and the modality of the links as concrete historical circumstances; which are broad patterns of historical contingencies.

To some extent, the reasoning that occurs in Marx's analysis of the value form takes historical contingencies as grist for the conceptual mill; like the illustrative examples he uses which are clearly inspirations for him. This facilitates analysing the relationship of historical patterns by developing a web of concepts to link them. We don't look down at a good model's mathematical derivation for falling out of links of conceptual necessity because Nature hasn't derived it that way; we judge the derivation of the model on how well it captures the constitutive relations of its targeted phenomenon. (@Pierre-Normand due to similar themes from discussion 'Carlo Rivelli's...')

While it is nice to go through other bits of theory, like with @andrewk's kindly given examples about value and price, or @ssu's points earlier about the organisation of money being focussed on debt creation and management; I want to keep the thread on topic in the long term. So if these things touch on what's in the text so far, and their reference is needed to make a point, so be it. Otherwise, leave it. -

Marx's Value TheorySo if Marx wants to explain how a commodity comes to have any value at all, he's right that labor costs are a factor. If he wants to explain where money actually comes from, there are a few more pieces of the puzzle to dig up. Perhaps he'll get to that in the next chapter. — frank

I get the sneaking suspicion that you're not putting much effort into studying the book or my exegesis of it. In one of the opening posts I highlighted that Marx's analysis begins with the myth of barter rather than a robust history of trade; so it shouldn't be expected to have all the historical specifics of the development of capital right. Regardless, he has to give an account of all the moving parts in his ideas before knotting them together right.

This is what made the first exegesis I did, of the money commodity and money form explicitly, gloss over the details which I'm now working on.

So yeah, the historical development of money is interesting; but his analysis turns on does he have an accurate picture of how value, money and the like work in a capitalist system of production rather than did he deduce the value form from more appropriate anthropological records.

Yes, currency tokens redeemable in specific amounts of goods are the historical ur-form of money. Yes, this implicates debt and property relations as co-emergent with currency (which Marx acknowledges; see references to money of account and the property relations inherent in C-M-C' an M-C-M' in my opening posts). Yes, 'gift economies' with incredibly complicated social norms of repayment are as old as humans making stuff in communities. If this endangers Marx's account I'm all for exploring it; but you keep contrasting your points to your misconceptions (like 'labour costs' and your continual mixing up of value and price) rather than to Marx's account or my exegesis. -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical Platonism

I thought you'd be interested on Terence Tao's thoughts on the development of mathematical skill. He has three distinct stages of competence:

(1) Pre-rigorous; like manipulating apples on a table, 2 apples plus 3 apples is... count them.... yes! 5 apples. Or later: 'the derivative of a function is the slope at that point... look if we take the derivative formula for x^2 - yes class that's 2x - and line it up with the point (1,1) on the line, yes! you can see the slope is the same as 2x'.

A pre-rigorous stage mathematician has enough of a feel for a topic to perform basic computations; they will form non-systematic insights and heuristics which they cannot easily translate into formal mathematics. They can follow handle-crank rules without any intuition as to why it works.

A good example here is, probably what most people still have, the ability to times 47 by 12 through the algorithm which looks like:

47

12

-----

and by carrying tens and so on. Most of us could do this with some degree of effort, but god knows precisely how it works. It usually occurs while young and inexperienced with a topic; spanning pre-university and some undergrad education.

(2) Rigorous: like learning how to prove 1+1=2 through a set theory or the Peano Axioms, or how to define fractions and real numbers consistently; epsilon-delta and epsilon-N 'turn the handle' proofs for convergence and continuity. Manually computing derivatives from their definition. This usually occurs mid-undergrad until the masters thesis on a topic, or advanced modules on topics.

A rigorous stage mathematician largely learns definitions and computes proofs and more advanced calculations by reducing them to simpler ones.

Developing the example; a rigorous stage mathematician would be able to prove why the above algorithm for computation works: you can do this by formally summing the stages:

2*7=10+4, remove tens to obtain the units digit, 4, store 10 to the tens computation (total sum 4)

2*40=80, now 90 while adding the 10 (total sum 94)

end stage 1

0*47=0

10*47=470, add previous total sum yielding 564

end

2*7+2*40+10*47=2*(47)+10*47=12*47

(3) Post rigorous: a post-rigorous mathematician can reason intuitively and through analogy about mathematical structures, their intuitions and analogies usually can be translated into proofs, or they will have the ability to find counter examples. The post rigorous stage can be obtained by mathematicians by updating intuitions formed in the pre-rigorous stage to respect the formalisms learned in the rigorous stage. This obtains after advanced modules or long theses are completed, typically the sphere of research or practicing mathematicians in their required competences.

A post rigorous modification of the above algorithm works to compute the product in binary:

details12=0*2^0+0*2+1*2^2+1+2^3=b=1100

47=1*2^5+0*2^4+1*2^3+1*2^2+1*2+1*2^0=101111

101111

1100

gives

0

0

010111100

101111000

2^0 col = 0

2^1 col = 0

2^2 col = 1

2^3 col=0 carry 1

2^4 col = 1 carry 1

2^5 col = 1 carry 1

2^6 col = 0 carry 1

2^7 col = 0 carry 1

2^8 col = 0 carry 1

2^9 col = 1

2^9=512, 2^5=32,2^4=16,2^2=4, 512+52=564

1000110100

I winged this off the intuition that 'carry the ten' was the same as 'carry the base' and filled out the details later.

To be sure, post-rigour is topic specific; while I'm sufficiently familiar with positional notation and base changes to intuit quite a lot about them, I'm nowhere near as familiar with formal proofs in ZFC, so I couldn't wing deductions in ZFC by 'getting the right idea' first then 'working out the details'.

The motivation for bringing this up being that how the conceptual links work between synthetic a-priori propositions, or synthetic a-priori ideas/intuitions, are competence dependent and topic specific. Which isn't to say that the fact that the algorithm above generalises to any base system is dependent upon my competence, but the expression of that fact depends entirely on the 'right links' and 'right intuitions' being in place in their expresser. So there's a historical component to it; there's no way I'd've been able to wing the above generalisation without floating point arithmetic, hex and binary manipulations being part of computing courses. Having the 'right links' and 'right intuitions' is as much a function of the intellectual milieu as creative competence. -

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Climate ChangeLet's hope that there's enough petroleum left to synthesise the required petrochemicals to meet the budding renewable demands of the apocalypse.

-

Marx's Value TheoryThe remainder of the section is mostly reiteration through an example, going through Aristotle's analysis of value:

The two latter peculiarities of the equivalent form will become more intelligible if we go back to the great thinker who was the first to analyse so many forms, whether of thought, society, or Nature, and amongst them also the form of value. I mean Aristotle.

In the first place, he clearly enunciates that the money form of commodities is only the further development of the simple form of value – i.e., of the expression of the value of one commodity in some other commodity taken at random; for he says:

5 beds = 1 house (clinai pente anti oiciaς)

is not to be distinguished from

5 beds = so much money. (clinai pente anti ... oson ai pente clinai)

He further sees that the value relation which gives rise to this expression makes it necessary that the house should qualitatively be made the equal of the bed, and that, without such an equalisation, these two clearly different things could not be compared with each other as commensurable quantities. “Exchange,” he says, “cannot take place without equality, and equality not without commensurability". (out isothς mh oushς snmmetriaς). Here, however, he comes to a stop, and gives up the further analysis of the form of value. “It is, however, in reality, impossible (th men oun alhqeia adunaton), that such unlike things can be commensurable” – i.e., qualitatively equal. Such an equalisation can only be something foreign to their real nature, consequently only “a makeshift for practical purposes.”

Aristotle therefore, himself, tells us what barred the way to his further analysis; it was the absence of any concept of value. What is that equal something, that common substance, which admits of the value of the beds being expressed by a house? Such a thing, in truth, cannot exist, says Aristotle. And why not? Compared with the beds, the house does represent something equal to them, in so far as it represents what is really equal, both in the beds and the house. And that is – human labour.

The last paragraph, however, introduces some new material; the value form is a historical/contingent mechanism that comes along with societies organised consistently with it and those which either do not prohibit or promote its development; it is not a transhistorical feature of exchange.

There was, however, an important fact which prevented Aristotle from seeing that, to attribute value to commodities, is merely a mode of expressing all labour as equal human labour, and consequently as labour of equal quality. Greek society was founded upon slavery, and had, therefore, for its natural basis, the inequality of men and of their labour powers. The secret of the expression of value, namely, that all kinds of labour are equal and equivalent, because, and so far as they are human labour in general, cannot be deciphered, until the notion of human equality has already acquired the fixity of a popular prejudice. This, however, is possible only in a society in which the great mass of the produce of labour takes the form of commodities, in which, consequently, the dominant relation between man and man, is that of owners of commodities. The brilliancy of Aristotle’s genius is shown by this alone, that he discovered, in the expression of the value of commodities, a relation of equality. The peculiar conditions of the society in which he lived, alone prevented him from discovering what, “in truth,” was at the bottom of this equality.

That concludes the section on the equivalent form. Marx then synthesises his sections on the relative form and the equivalent form into a deeper exegesis of their composite; the elementary form of value. -

Marx's Value TheorySo far we have that if 'x coats is worth y yards of linen', the exchange value of the x coats expresses itself as a definite quantity ( y ) of the use value linen. Underpinning this is that the concrete labour which produces x coats meets the concrete labour which produces y yards of linen as abstract labour to abstract labour; they are only comparable once all qualitative particularities are filtered out which are not shared between both.

This means the commodity functioning as the equivalent expresses the value (exchange value) of the commodity in the relative position by being a definite quantity of a use value whose constitutive labour counts alone as abstract labour.

So we have that from the view of the exchange relation concrete labour inverts to abstract labour and expresses it in productive activity; contemporaneously use value inverts to exchange value (for commensurability) and back again (as a magnitudinal property, duration). Along with this the private labour which makes each commodity expresses itself solely as the character of social labour which is required for the production of any commodity. Marx continues:

Hence, the second peculiarity of the equivalent form is, that concrete labour becomes the form under which its opposite, abstract human labour, manifests itself.

But because this concrete labour, tailoring in our case, ranks as, and is directly identified with, undifferentiated human labour, it also ranks as identical with any other sort of labour, and therefore with that embodied in the linen. Consequently, although, like all other commodity-producing labour, it is the labour of private individuals, yet, at the same time, it ranks as labour directly social in its character. This is the reason why it results in a product directly exchangeable with other commodities. We have then a third peculiarity of the equivalent form, namely, that the labour of private individuals takes the form of its opposite, labour directly social in its form.

We have a little composite of linked abstractions which transform each-other in exchange:

The use value in the equivalent form expresses the exchange value of the relative form through their exchange ratio; the commensurability of the use value in the relative position and of the use value in the equivalent position is ensured by the two meeting as abstract labour alone; which forces the concrete labours of their production to act as the expression of their abstract labour; which ensures that the private labour of individuals insofar as it produces commodities is always already social labour. -

SubjectivitiesIs that possible to try to broaden farther the notion of trauma to explain child’s integration into pedagogical institutions? When a child for the first time brought to a kindergarten, she finds herself in the entirely new environment, has been forced to adjust her behavior and habits to a set of institutional norms and rules. — Number2018

I don't think trauma does all the work of subjectivity as an idea, but I think it's a pretty good example of how a subjectivity works. I think it emphasises a few important things about subjectivity vs thinking about stuff in terms of consciousness and objects or subjects and roles/properties:

- Subjectivities are more than roles, they become integrated capacities of a person which are exercised in how they live their life.

- Subjectivities are more than the application of an on-off property to a subject, like 'disabled' or 'traumatised'; they can inform and transform people in different degrees of similar ways; like episodic flashbacks vs more mundane intrusive memories; or in much different ways; like generalised anxiety vs dissociative disorder as comorbidities of PTSD.

- Subjectivities are to a large degree impersonal; they are composite patterns of behaviours, feelings and events which constrain individuals along a mode of variation. A person can be said to 'inhabit' the unfolding of PTSD just the same as they can inhabit walking; being a sufferer of PTSD or a walker respectively.

-

Is there such a thing...?Stolen consent might not be defined, but manufactured consent is probably well understood at this point!

-

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical Platonism

In defense of a dogma seems like a really fun article. I just started it and I'm impressed by the style, precision and generosity of the argument! -

SubjectivitiesSo: A common notion that is often discussed in philosophical literature is that of varying kinds of subjectivities. As I hinted in the note' above, these 'subjectivities' have nothing to do with 'consciousness' and have everything to do with one's range of capacities in a particular situation. A 'subject' here is one that can act or be acted upon in a range of ways, depending on the context at hand; so, for example, one can speak of a subject of street-walking: the subject of street walking is involved in traversing a certain terrain, in making a way to a destination, of admiring sights, of avoiding traffic, of waiting at traffic lights, and so on. There is a kind of subjectivity involved in being a walker of the streets, that is not the same as that involved in say, playing chess. — StreetlightX

I wanted to chime in with something that looks to me as an example, though I'm mostly thinking of subjectivities in the Badiou-ian sense of 'subject-to/of-event'; out of the vocabulary this is when something happens that reconfigures how people inhabit the world; which, interchangeably, changes who they are.

Street's example of someone walking and there being a subjectivity associated with it does a good job of highlighting how pervasive subjectivity in the OP sense is, but I imagine it can be a difficult jump to go from something which is so mundane and 'experienced passively' during the business of living to thinking of walking as something which structures how you live your life.

A more clearcut example might be someone with PTSD as a result of a childhood trauma. Let's imagine that a kid's hand was held onto a hot frying pan for punishment until they started screaming. They go through their childhood living in a state of confused fear, but otherwise coping. They finally have their 18th birthday and move out of the house, with some resentment for their parents for being the kind of assholes that would give second degree burns as punishment. They start making out with someone at university in a club, then this someone touches the sufferer's wrist.

Boom, immediate panic attack and intrusive memories, the person holding their wrist becomes a threat, the once familiar club becomes a foreign and threatening land, and they need to escape. They break off their impromptu make out session and hurry home, breathing heavily in confused panic.

Over the next year or so, they begin remembering more and more incidents which have been marked by shame and dread, some from their early childhood and some from later; maybe they always felt everyone hated them at school for no reason, maybe they always felt cripplingly lonely but afraid of people. It's all associated with the disgusting, abusive memories. The violence that was done to them, once invisible, becomes visible. They can't help but inhabit the world in this difficult way now their normal has been revealed as a mechanism of pain.

Their friends, seeing someone behaving strangely, tell them to get a grip, but it's difficult for the victim; their mind sometimes works normally and sometimes is a torture house. They can't just become a passive experiencer of the wake of their trauma again. Their habits and personality were formed in the wake of their trauma, and only later did it catch up to them; when they felt things were normal, and suddenly they were not.

I would suggest that similar things happen even with walking, seeing a child playing in traffic produces an involuntary response; run to help or freeze in terror. This is because we know the norms and know the dangers... But not just know or feel or experience, we only have those attitudes because we live in way which affords them. -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical PlatonismI think that's a point Plato would readily have acknowledged; and a reason why Plato may never have been a Platonist in the modern sense of the term. Modern mathematical Platonism likely is a distortion of Plato's thought, which distortion arose from taking his metaphors literally and misconstruing acts of the intellect -- themselves always portrayed by Plato as outcomes of strenuous and protracted dialectical effort -- as passive acts of contemplation of an independently constituted domain. — Pierre-Normand

This makes sense. I don't have the knowledge to bring out how Plato became distorted, though. What history are you tracing in this idea? -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical Platonism

Then it's wrong. You don't actually need to go to category theory for objects which don't exist in the ZFC universe, certain large cardinals need extra axioms to model. -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical Platonism

Do some reading about it. Essentially small categories are those which have representations as sets and set relations/operations. Not all categories are small categories. So the link provides a starting point to start learning about under what conditions a category can be represented by a set! -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical Platonism

Except it isn't any more! There's more to mathematics than what can be represented through set theory. -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical Platonism

That's not how that works. There are more categories than the category of sets, Set. Only things in Set are categories which can 'be instantiated' in sets. -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical Platonism

Trying to give examples of 'non-mathematical' math from the canon of mathematics is a poisoned well. But I did try to give some demonstratively weird objects in my response to litewave. There are also some suggestive examples. EG, every number we're ever going to see as a digit based representation is computable, but computable numbers are a measure 0 set in the real line which is their home. We have a rich mathematical theory about continuous functions, augmented it with continuously differentiable and smooth functions, regardless generic continuous functions are nowhere differentiable. Generic functions themselves are nowhere continuous. Ways of associating elements of sets with elements of other sets generically are not functions, either.

If we have that derp face from before as a constant symbol, it satisfies the axioms of a group on a single element. We could make the same generalisation with any addition of a black pixel somewhere in the plane to the image, and we have countably infinite isomorphic copies of the group on one element that are literally just derp faces. If you were to write all of them down and establish the isomorphisms between the different representations, that's more mathematics than will ever be written solely devoted to the stupid application of an algebraic structure to the derp face.

All of these are in the elemental plane of mathematics. But they too are relatively well behaved.

Given the tiny frequency of tame objects in the vast sea of batshit lunacy that are models of some collection of axioms, it would be very hard to claim that generic mathematical objects typically are interesting or resemble/are related to the ones whose study constitutes what could be topics of mathematical study. We don't just not care about them for reasons of utility, we don't care about them because we have a standard of intelligibility which automatically excludes them from our mathematical discourse.

Yes yes, the Platonist will insist, they're still there, even though they can't be instantiated in our mathematics. But that still concedes enough for them to hang themselves with; this is our mathematics, it's mathematics for us by us, it's not an independent realm of existing objects at all, it's a conceptual web whose contours are delimited by our standards of intelligibility. All of that is mathematics, and no more.

Edit: previously I had an example of adding different multiplicative 0's to our usual arithmetic in this post, which satisfy the property of 0 like a*x = x*a=a for all other numbers x, where a is now the extra 0, but if I took another 0, b, I would have that a=a*b=b through the definition. This was based around a vague recollection from university but I obviously didn't remember it properly and I can't figure out how to set it up exactly again. In lieu of that, if we have a less restrictive 'left 0' so that a*x=a for all x, I can add any number of leading extra 0's. If you are reading this and have already read my unedited post, sorry for the flub. -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical Platonism

Well no. There's nothing like what there would be if all the mathematical forms instantiated in the same way. Which really raises the question - when we recognise an instantiation of a mathematical object, with our platonist goggles on, are we seeing the world conforming to mathematics or mathematics conforming to the world? Sometimes we will see mathematics conforming to mathematics, but that's of no interest here.

We already have to filter out the junk in the platonic realm to obtain something resembling the collection of mathematical objects we are familiar with; what if this filter was internal to mathematics as a field of study, and roughly demarcated its contours of relevance and topics of interest?

Under that presumption, the realm of mathematical entities sure does look a lot more like its current self. -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical Platonism

If the platonic realists are right, the name of that junkyard is the Platonic realm of forms. -

Disappearing post.

You just thanked me. There is no need to thank me again within 3 words. But thank you for thanking me, and thanks. I will close the thread now.

fdrake

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2025 The Philosophy Forum