-

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical PlatonismIn set theory, all relations are defined as sets. — litewave

But how mathematics looks as a category theorist is quite a lot different from how it looks like under the aspect of set theory. Say, to a category theorist, natural numbers don't look like the names of individual objects, they look like isomorphism classes of sets. Set theory was built out of intuitions about composite objects of multiple elements, category theory was built from intuitions of transformation and symmetry.

Yes, most of it might not be beautiful or useful but we are talking about metaphysics, which I don't think depends on subjective notions of beauty or usefulness. — litewave

I have no idea how you took the main thrust of my post to be about beauty or truth. The main thrust is simply that most mathematical objects aren't worthy of study, and agglomerating them all together; producing the final book and the final theorem, far from the ideal vision or ultimate goal of mathematics - produces a writhing mass of irrelevant chaos. It's less Heaven, more Pandemonium.

At least as many pages in The Great Book Of Mathematics from this realm would be devoted to this picture:

as all of the research we have done and will ever do in mathematics. You shouldn't come away from this thinking about the the relationship of mathematics to the form of derp face... -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical Platonism

As I read it there are two complementary thrusts; one is showing what kind of crazy thing the elemental plane of mathematics is (would be) and that it doesn't resemble mathematics as we study it (or its objects) at all, the other is by looking at what kind of selection criteria we use for things which are part of mathematics as a field of study. I think the first one is a better intuition pump, but the second one is a more fleshed out argument. -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical Platonism

There are other foundations of mathematics which are currently in use. Even one which highlights explicitly that mathematics studies relational structures; in category theory, the category Set is a subcategory of the category of relations, Rel. The paper in the OP even points this out, referring to topos and category theory among other things.

But anyway, the thrust of the argument is: if we took the results of all possible axiomatic systems, agglomerated them into one giant object, then granted that object independent existence - what would it look like? It would contain all kinds of bizarre crap, navigating through this world you'd hardly ever find an axiomatic system which resembled anything like our own. I imagine if Bertrand Russel visited this elemental plane of mathematics, he would make observations like:

Oh dear, I seem to have stumbled over a strange sort of arithmetic with countably infinitely many things which seem like 0 insofar as 0*a=a*0=0 for each one but a+0 isn't 0+a isn't a, ever!

Looking over the graphical representation of the function, we see that it satisfies f(x+y)=f(x)+f(y) but it isn't anything like our normal linear operators! It's everywhere dense in the plane, help!

Some mother fucker over there glued a cardinal between Aleph-0 and Aleph-1 copies of the real line together...

He wouldn't make a statement like:

Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty—a beauty cold and austere, like that of sculpture, without appeal to any part of our weaker nature, without the gorgeous trappings of painting or music, yet sublimely pure, and capable of a stern perfection such as only the greatest art can show.

because there's no way in hell he'd even be able to find such sensible structures in this existence turned madhouse. The most sensible explanation for why mathematics as a field looks nothing like this writhing chaos is that mathematics is sustained through the refinement of diamonds into more diamonds, and finding new ways of mining them. It is the study of fruitful relations and structures for us, not panning the sewage which is the elemental plane of mathematics for gold.

If such a realm really does instantiate into ours, it's an incredible coincidence that so little of it resembles mathematics as a topic of study, no? -

On the Great GoatI heard that the Great Goat is in a goat pen, but really it's the rest of being which is in the pen.

-

Causality conundrum: did it fall or was it pushed?What is surprising? The indeterminism is uprising, but the time symmetry is expected since the laws of motion are time-symmetrical. — Pierre-Normand

I think we meant different things by indeterminism. In the paper's sense of 'a single past can be followed by many futures', the translational time symmetry of the non-zero solution is what facilitates that conclusion. If the ball decides to fall in a given direction, its behaviour is determined at every point on that path by the equations of motion (after redefining t-T=0).

Nevertheless, this collapses the issue to a one spatial-dimension one time-dimension problem- we have a radial direction and the time parameter, and the equations of motion are defined in terms of a radius which is a function of time. So it's pretty clear that the dynamics is radially symmetric.

What I was missing is that when we collapse down to a vertical cross section of the dome, then remove half of it (going from something that looks like /\ to something that looks like /), the one dimensional version of the problem exhibits the time symmetry.

What the radial symmetry highlights is 'the same future can be held by many pasts', where a future includes 'choosing' a direction to fall in, the time symmetry (specifically talking about the mapping t->t-T which shows up in the solution) highlights 'the same past can be held by many futures'. I was mixing up the two in my head. -

Causality conundrum: did it fall or was it pushed?

Doesn't really matter what point I'm making for the purposes of the discussion, seeing as it's moved on. All I'm saying is that mapping t->t-T is a symmetry of the laws of motion here, but so is rotating the force vector; any path that the ball could take down the object would follow Newton's laws at all time, even though the arbitrary start time and arbitrary falling direction are unspecified. The major difference between the two in my reading is that the problem is 'set up' to be radially symmetric and so we're primed to think of the problem as of a single dimension (the radial parameter), but the time symmetry falls out of the equations and is surprising. -

Causality conundrum: did it fall or was it pushed?

See the point. Perhaps I'm too poorly attuned to physics to see much of a distinction between a time symmetry and a radial one. -

Causality conundrum: did it fall or was it pushed?

Specifically it's that no force (0 vector) is applied as an initial condition while the ball is at the apex that leaves room for the indeterminism. -

Causality conundrum: did it fall or was it pushed?I think the discussion moved on, but I wouldn't trust using the higher derivatives of radial displacement here to mathematically isolate a cause for the ball rolling. The radial displacement and higher derivatives are constant over direction - thus regardless of the indeterminism of the initial parameter, the direction the ball falls is also of the same character; undetermined by the model but consistent with its equations.

IE, so even if we specified a starting time for the ball rolling, that's still an incomplete description - we need a start time and a direction. -

Marx's Value TheoryMarx analogises value to weight:

One of the measures that we apply to commodities as material substances, as use values, will serve to illustrate this point. A sugar-loaf being a body, is heavy, and therefore has weight: but we can neither see nor touch this weight. We then take various pieces of iron, whose weight has been determined beforehand. The iron, as iron, is no more the form of manifestation of weight, than is the sugar-loaf. Nevertheless, in order to express the sugar-loaf as so much weight, we put it into a weight-relation with the iron. In this relation, the iron officiates as a body representing nothing but weight. A certain quantity of iron therefore serves as the measure of the weight of the sugar, and represents, in relation to the sugar-loaf, weight embodied, the form of manifestation of weight. This part is played by the iron only within this relation, into which the sugar or any other body, whose weight has to be determined, enters with the iron. Were they not both heavy, they could not enter into this relation, and the one could therefore not serve as the expression of the weight of the other. When we throw both into the scales, we see in reality, that as weight they are both the same, and that, therefore, when taken in proper proportions, they have the same weight. Just as the substance iron, as a measure of weight, represents in relation to the sugar-loaf weight alone, so, in our expression of value, the material object, coat, in relation to the linen, represents value alone.

which is similar in function to the earlier analogies of chemical formulae and area, and like area exhibits a property with magnitude. However, unlike weight, value is not imbued upon the commodity through its physical constitution alone:

Here, however, the analogy ceases. The iron, in the expression of the weight of the sugar-loaf, represents a natural property common to both bodies, namely their weight; but the coat, in the expression of value of the linen, represents a non-natural property of both, something purely social, namely, their value.

it is rather imbued upon the x and y in 'x is worth y' through the social relation of their labours; that is insofar as both x and y are embodiments of human labour in the abstract.

Since the relative form of value of a commodity – the linen, for example – expresses the value of that commodity, as being something wholly different from its substance and properties, as being, for instance, coat-like, we see that this expression itself indicates that some social relation lies at the bottom of it. With the equivalent form it is just the contrary. The very essence of this form is that the material commodity itself – the coat – just as it is, expresses value, and is endowed with the form of value by Nature itself. Of course this holds good only so long as the value relation exists, in which the coat stands in the position of equivalent to the linen.[22]

Above, Marx summarises before moving on to a more metaphysical interpretation of the same idea:

Since, however, the properties of a thing are not the result of its relations to other things, but only manifest themselves in such relations, the coat seems to be endowed with its equivalent form, its property of being directly exchangeable, just as much by Nature as it is endowed with the property of being heavy, or the capacity to keep us warm.Hence the enigmatical character of the equivalent form which escapes the notice of the bourgeois political economist, until this form, completely developed, confronts him in the shape of money. He then seeks to explain away the mystical character of gold and silver, by substituting for them less dazzling commodities, and by reciting, with ever renewed satisfaction, the catalogue of all possible commodities which at one time or another have played the part of equivalent. He has not the least suspicion that the most simple expression of value, such as 20 yds of linen = 1 coat, already propounds the riddle of the equivalent form for our solution.

We do not see the social relation which imbues commodities with their values in the exchange relation of relative and equivalent, so it appears as if only the physical properties of both commodities can serve to facilitate the comparison of their value. Nevertheless, Marx suggests that the exchangeability of two commodities and their exchange ratio is based upon a property of the coat (that it is a product of labour) and that property's relationship to other commodities (the relative magnitudes of their socially necessary labour times). Value persists in the relation of commodities and labours but nevertheless expresses itself as a definite property of the object; which is to say that Marx sees the value form as a social fact which imbues products of labour with value once entered into the exchange relation - once subsumed to the value form.

In a similar way to how use values are the form of manifestation of exchange values in the value form, concrete labour is the form of manifestation of abstract labour; Marx exploits the structural symmetry that was exhibited earlier:

In tailoring, as well as in weaving, human labour power is expended. Both, therefore, possess the general property of being human labour, and may, therefore, in certain cases, such as in the production of value, have to be considered under this aspect alone. There is nothing mysterious in this. But in the expression of value there is a complete turn of the tables. For instance, how is the fact to be expressed that weaving creates the value of the linen, not by virtue of being weaving, as such, but by reason of its general property of being human labour? Simply by opposing to weaving that other particular form of concrete labour (in this instance tailoring), which produces the equivalent of the product of weaving. Just as the coat in its bodily form became a direct expression of value, so now does tailoring, a concrete form of labour, appear as the direct and palpable embodiment of human labour generally. -

Marx's Value Theorycontinuing developing the account of the equivalent form of value.

The first peculiarity that strikes us, in considering the form of the equivalent, is this: use value becomes the form of manifestation, the phenomenal form of its opposite, value.

This references that when 'x is worth y', the way the value of x is expressed is as a specific quantity of the use value y. This means, when entering into exchange, use values are the medium for the expression of value through the quantity of the use value.

The bodily form of the commodity becomes its value form. But, mark well, that this quid pro quo exists in the case of any commodity B, only when some other commodity A enters into a value relation with it, and then only within the limits of this relation.

this is to say that quantities of use values operate as the form of manifestation for value only when considering a commodity under the aspect of exchange; that is, only when considering them insofar as they are subjected to the value form.

Since no commodity can stand in the relation of equivalent to itself, and thus turn its own bodily shape into the expression of its own value, every commodity is compelled to choose some other commodity for its equivalent, and to accept the use value, that is to say, the bodily shape of that other commodity as the form of its own value.

This is a reiteration with a different emphasis. Saying 'x is worth x' says nothing about the value of x, x is always worth itself. So if we want to ascertain the value of x, it needs to be compared to an amount of a y. What determines the amount of y is the abstract labour embodied in the amount of x.

Nevertheless, I have argued elsewhere that so long as we are considering that a commodity has already been brought into the exchange relation with another commodity, we can assume its value has found an expression and treat 'x is worth x' as a harmless tautology rather than a breakdown of the relative and equivalent form. -

Marx's Value Theory

I don't think this is too different for Marx from the two islands example. We're in a state of transition between two socially necessary labour times - when the minimum labour time is not equal to the modal one, so the comparative advantage Lakshmi has can be described by her unique ability for more productive labour of the same commodity. She can produce the same good quicker than the norm, so she produces more value per hour of her labour regardless of how long she spends doing it on any day. The 'normal' conditions of production set the value even in a period of transition to a new normal; so any averaging or other statistical operations that summarise the value are to be done over the productive processes, rather than the produced goods.

I'm also pretty sure that for Marx supply and demand influence the price of commodities but not necessarily their value. Supply can be linked to productivity a little; insofar as if it takes x amount of time to produce y of the good, the yearly rate of production, say, could be lower than the per day on-season rate due to seasonality or other constraints. So a 'scarce' commodity could be scarce because it has a very low rate of production. Supply and demand will (ideally) influence how much of a commodity is produced, but not the time required for the production of a single unit of that commodity. In this way, the accumulated value of all commodities in a productive network tracks the extent and efficiency of automation and the (an) average of the costs for an hour of labour closer than it tracks changes in demand or supply of any group of commodities made in that productive network.

There's little reference to supply and demand in the first chapter of the book, where Marx is detailing the fundamental parts of his theory of value. He deals with the relationship between valueless goods; like non-commodities which are that in virtue of no physical form, or unprocessed assets; and those with value much later in the work, specifically in volume 3 in terms of fictitious capital. -

Marx's Value Theory

Thank you for your input. The questions are interesting, but I cannot do Marx while drunk. You will have to wait a bit. -

Marx's Value Theory

The stakes in Marx's value theory are how do commodities obtain their values in a capitalist society. He's especially interested in how money gets its value - not just that it has a value, but also the magnitude of its value.

The book starts off analysing the conceptual structure of exchange - his value theory -, he relates it to work -the labour theory of value and of labour in capitalist production as value productive -, only after touching on labour as value-productive does he start analysing exchange networks (the next full chapter is on the circulation of commodities and the circulation of money).

Edit: It's also really really necessary to keep in mind that when Marx talks about value, he isn't talking just about price. Pricing mechanisms are a related but distinct topic of inquiry. EG, for Marx, things like unprocessed oil reserves or unworked land don't have a value even though they can be bought for money. -

Marx's Value Theory

The analysis begins with the trade of one item for another. The items which are traded are called commodities. Commodities have a technical sense here, as they are items which have a component of 'use value' - the utility they serve, like wearing clothes or eating food - and 'exchange value' - the value they take in exchange.

In exchange, the value of one item, say 1 yard of linen, is equated to another item, 1 pair of trousers. If we write "1 yard of linen is worth 1 pair of trousers', Marx calls the first bit the 'relative form', here the 1 yard of linen, and the second bit the 'equivalent form', here 1 pair of trousers.

Towards the start of the thread; when I went through a very dense summary of my understanding of Marx's value theory; you'll have seen me talking about the expanded form of value and the money commodity.

The expanded form of value for, say, for the 1 yard of linen, is the set of all commodities which could be exchanged for 1 yard of linen as an exchange of equivalently valued goods.

The money commodity, Marx's example (and he stresses that it's just an example), is gold. Gold functions as the money commodity by serving as a universal equivalent. A universal equivalent is the commodity using which the values of all other commodities are expressed. So instead of say:

1 yard of linen is worth 1 pair of trousers

1 yard of linen is worth 2 coats

1 yard of linen is worth 900 eggs

we end up with

1 yard of linen is worth 0.5g of gold, say

and 1 pair of trousers is then worth 0.5g of gold

and 900 eggs is worth 0.5g of gold.

...

and so on for all commodities which have the same value as 0.5g of gold

The social function of currency is to serve as a representative of the set of commodities which have that value. Any fiat or digital currency functions as a universal equivalent because it maintains the social function of money, even though it is no longer redeemable as a specific commodity through an institution (like the Bank of England). A token representation of value (currency) functions in just the same way as a universal equivalent (but of course it will differ in laws surrounding it and how it may be manipulated).

When we end up with a privileged representation of a set of commodities of equivalent value, we have a money commodity. When that's abstracted to a fiat currency, it's the same mechanism with different legal and institutional backing/enforcement required.

The reason I haven't addressed money commodities or fiat currencies (or even the expanded form of value and the universal equivalent) with my more detailed exegesis is just because they come later in the chapter. -

Marx's Value Theory

Sorry. I guess I'm not sure which part to explain because I dont know where our interests intersect. — frank

You make interest in what interests you by explaining it well. -

Marx's Value Theory

Responding to (2) first:

There are scenarios where the assumption that the value of a commodity equals the socially necessary labour time doesn't hold. I wrote about this by introducing the distinction between productive equilibrium and productive disequilibrium.

(1) Productive equilibrium is the state of a distribution of labour times for a commodity when its minimum equals its mode.

(2) Productive disequilibrium is the state of a distribution of labour times for a commodity where its mode is greater than its minimum.

Under these assumptions, the paired island economy is in a state of productive disequilibrium because each produces C and D with different socially necessary labour times. The distribution is also bimodal as there are two local maxima; corresponding to the labour time of A producing C and B producing C. The same holds for A producing D and B producing D.

I think this example is a bit of a toy problem and doesn't really reflect the conditions in the economy at large, but I think it's worthwhile seeing if analysing things in terms of their labour times producing a mutual advantage through exchange.

If we assume that we're analysing per day per person, we have 24 hours of labour time to spend on producing C and D. This means that there is a trade off in the productions of C and D for both islands, and both islands have a maximum amount of each they could produce. So we end up in the situation where a proportion of 24 hours is spent producing C and a proportion is spend producing D. This holds for both A and B, and both have different productivities for C and D. This gives the equations that govern the total daily production as:

Production on A = x1*p1 C + y1*(1-p1) D

Production on B = x2*p2 C + y2*(1-p2)D

where p1 is the fraction of hours spent on A producing C, x1 and y1 are the maximal per day productivities of C and D respectively on A. Analogously for B.

Assume wlog that x1>y1 and y2>x2 the sum of Production A and B is maximised in terms of the number of goods at:

x1C+y2D

under the assumption that the global maximum is the sum of the two local maxima.

So A is producing x1C and B is producing y2D. The spending strategies don't matter as both A and B are producing their maximal amount per unit time - assuming free trade both obtain more per day, as is classically concluded.

I would be extremely surprised if Marx wasn't aware of these ideas and I'm sure he thought of the two islands example when setting up his theory of value; as he frequently cites the originator of the example, Ricardo, and also believes that the division of labour increases overall productivity through specialisation (IIRC anyway, it's been a while since I read that bit).

I also don't really trust the example. Hand waving at 'free trade' doesn't work much for me, it could be the case that B simply wasn't productive enough to be of use to A, or that the exchange ratios are completely crazy.

Honing in on this - if we have it that x1:y2 is tiny, B might not be able to obtain enough of C or conversely for y2:x1 tiny A might not be able to obtain enough of D. The same could be said for any mechanism which fixes the exchange ratios, not necessarily just labour time. There have to be some regularity conditions on productivity and exchange for 'free trade' to be able to provide both islands with enough.

So if we assume that A produces m1+n1 of C, where m1 is the minimal amount of C which A needs, and that B produces m2+n2 of D, where m1 is the minimal amount of D which B needs, this leaves n1 to be traded for n2. We also have to assume, then, that n1 is enough of C for B and that n2 is enough of D for A. It could be that n1=0 and then both islands are screwed, and this is fully consistent with the scenario and 'maximal productivity' logic, even when, say, y1 is equal to x1. -

Moderators: Please Don't Ruin My Discussions

Honestly, if there weren't so many duplicate threads I wouldn't've merged yours with another; there would have been no need to. The reason I chose to merge the other one into yours was because your OP engendered more high quality responses. Again, I'm sorry this has irritated you, and I can understand if you want to hold a grudge. -

Moderators: Please Don't Ruin My DiscussionsAs some way towards compromise I have inserted Snoring Kitten's comment in the thread with a disclaimer before the replies in the first page of the discussion. I had to edit one of Vagabond Spectre's posts to highlight that this occurred.

-

Moderators: Please Don't Ruin My Discussions

The reasons I made lots of merges were:

(1) There were a lot of active discussions on the front page with essentially the same content.

(2) The ones with sufficiently similar content got merged.

It wasn't a perfect fit, though none of them were. I am sorry that you feel it was inappropriate.

Regardless, your discussion is still active and on topic, so I won't change my mind about re-splitting it yet. -

Marx's Value TheoryMarx moves onto discussing the equivalent form more deeply.

Subsection 3: 3. The Equivalent form of value

Marx begins by restating the duality between the relative and equivalent forms:

We have seen that commodity A (the linen), by expressing its value in the use value of a commodity differing in kind (the coat), at the same time impresses upon the latter a specific form of value, namely that of the equivalent.

and draws out some of the implications about the equivalent form from the previous section explicitly:

The commodity linen manifests its quality of having a value by the fact that the coat, without having assumed a value form different from its bodily form, is equated to the linen. The fact that the latter therefore has a value is expressed by saying that the coat is directly exchangeable with it. Therefore, when we say that a commodity is in the equivalent form, we express the fact that it is directly exchangeable with other commodities.

Bolded bit: this is saying that 'x use value 1 is worth y use value 2' has the feature that the relative value of x use value 1 is expressed as y use value 2: that the value, despite being strictly social, is an evaluation of x use value 1 in terms of the concrete amount y of use value 2. This only occurs because x use value 1 is exchangeable for y use value 2.

When one commodity, such as a coat, serves as the equivalent of another, such as linen, and coats consequently acquire the characteristic property of being directly exchangeable with linen, we are far from knowing in what proportion the two are exchangeable.

Marx restates that the exchangeability of x use value 1 with y use value 2 as a determination of numerically identical values only makes sense upon the assumption that use value 1 is exchangeable with use value 2; this is because the numerical equivalence between them has to arise from somewhere; that they are exchangeable does not say how much one exchanges for the other.

I think a decent analogy here is blowing up a balloon. The points on the surface of a balloon are always connected, and if we say that two points on its surface are connected they are commensurate, then every point on the balloon becomes commensurate with every other by mere fact that it is a smooth, unitary surface without holes. However, that the balloon's points are connected/commensurate with each other tells us nothing about the distance of pairs of points; blowing up the balloon allows the specific distance of paths on the balloon surface to change without changing the commensuration which ensures the existence of those paths. The balloon itself is the form of value, whose magnitudes are determined by an external process.

The value of the linen being given in magnitude, that proportion depends on the value of the coat. Whether the coat serves as the equivalent and the linen as relative value, or the linen as the equivalent and the coat as relative value, the magnitude of the coat’s value is determined, independently of its value form, by the labour time necessary for its production.

Bolded bit is important. It characterises the value form - that is, at the minute, the duality of relative and equivalent, as the real abstraction driving the commensuration of commodities in definite amounts, whose definite amounts are given through the ratio of socially necessary labour times.

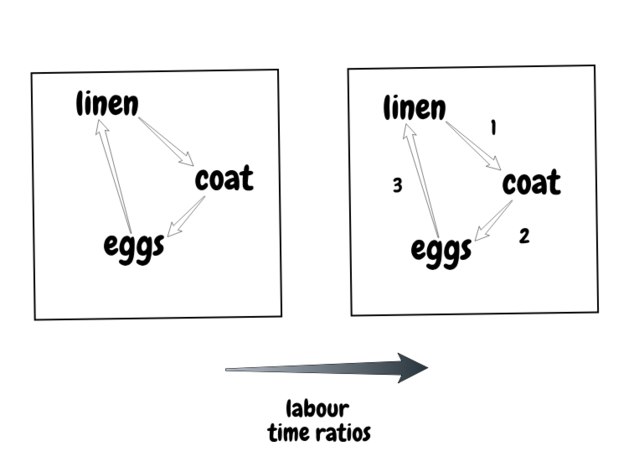

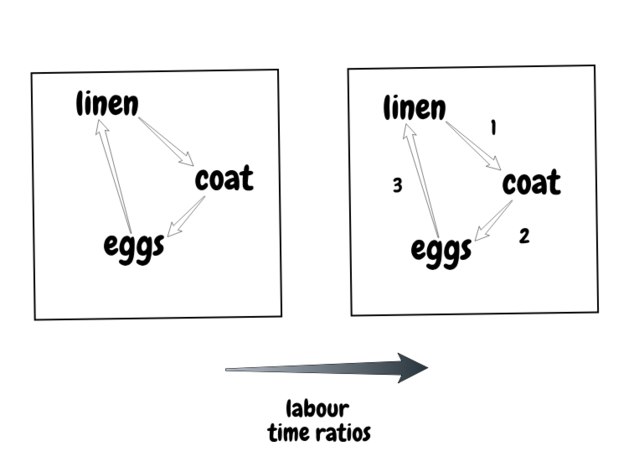

The balloon analogy is actually mathematically quite literal if we consider the relation T from before. The commensuration of entities is equivalent to the ability to exchange one type for another type; the amounts are given by the application of socially necessary labour time ratios. So the existence of a path between two commodity types is their commensuration, the weighting of that path with an exchange ratio determined by the ratio of labour times is the application of a magnitude. (Ignore that the arrows are one way here, the relation is really symmetric)

But whenever the coat assumes in the equation of value, the position of equivalent, its value acquires no quantitative expression; on the contrary, the commodity coat now figures only as a definite quantity of some article.

Marx gives us an example:

For instance, 40 yards of linen are worth – what? 2 coats. Because the commodity coat here plays the part of equivalent, because the use-value coat, as opposed to the linen, figures as an embodiment of value, therefore a definite number of coats suffices to express the definite quantity of value in the linen. Two coats may therefore express the quantity of value of 40 yards of linen, but they can never express the quantity of their own value. A superficial observation of this fact, namely, that in the equation of value, the equivalent figures exclusively as a simple quantity of some article, of some use value, has misled Bailey, as also many others, both before and after him, into seeing, in the expression of value, merely a quantitative relation. The truth being, that when a commodity acts as equivalent, no quantitative determination of its value is expressed.

To sum up, this characterises the relationship of relative and equivalent as:

(1) When a commodity assumes the relative form, and thus has an equivalent, the two must be exchangeable in order for one to be valued in terms of the other.

(2a) When we say 'x is worth y', this takes the value of x and represents it in terms of its exchange ratio with a definite amount of use value y.

(2b) 2a implies that y when serving as the equivalent has no expression of its value - IE, that the value form of dual relative and equivalents expresses solely the value of that commodity occupying the relative spot.

(2c) Nevertheless, the 'accidental position' of relative and equivalent can be reversed and we obtain a value expression for y in terms of x. -

There is No Secular Basis for MoralityMerging @Andrew4Handel's observations on religious morality to here:

What is a religious morality.

Do you have to believe in a particular religion to be moral by its standards. Could you for example follow the most of the ten commandments closely but be considered immoral because you don't believe in God?

Is it consistent to follow a religious morality closely but not believe the religion itself is true?

Is it hypocritical to pick and choose different parts of religions whilst ignoring or rejecting some of their central dogmas.

As someone who grew up in a strict religious environment I some times wonder about the possibility of being condemned because I no longer believe the religion and its values even if I have what appears to be very good or rational reasons not to do so.

Some religions demand blind obedience and or blind faith and appear to rely on fear to reinforce this.

Morality as commandments (deontology?) seems strong in one sense as being enforceable because the alternative maybe moral nihilism or uncertainty.

However religions tend to have unreasonable commandments and contradictions. -

Marx's Value Theory

I don't think any of the maths I've done so far makes predictions as such, though there have been a few nice theoretical results. One is that a system of exchange maintains the magnitude of value through trades if and only if you can't trade nothing for something. Soon there'll be a very easy demonstration that having strictly more stuff means you have strictly more value.

So spelling things out with mathematical structures like this isn't so much making novel empirical predictions, it instead should be judged on how well it ties lots of things which are expected to be true together in a nice way. In terms of faithfulness to Marx's ideas, using them should agree with how Marx uses them wherever possible.

That attempt at remaining in good faith is one of the reasons I spent so long trying to understand how subtraction works for commodities; because we know that goods can be removed from an exchange, but also that values are greater than or equal to 0 (since they're proportional to time). So while you don't see an account of 'commodity subtraction' in the book, I've used it to produce things which are in agreement with Marx' account. -

Marx's Value Theory

(1) He already does look at it mathematically. See recent post going through points I-III in the relative form, Marx is explicitly talking about how operations on labour time respect the 'is worth' relation. I'm mostly spelling things out explicitly that Marx already put in there. Another good example is his discussion over whether 'is worth' is reflexive ('x is worth x').

(2) It clarifies things, like why the elementary form of value doesn't have to preserve value magnitudes in trades, a puzzle Marx leaves for us. Also it shows how enforcing that trades preserve value magnitudes engenders a structural symmetry between values and commodities. These are just two examples.

(3) It's interesting to me. -

Marx's Value Theory

It also makes sense that if an organisation wants to increase their power and influence funding is required. Moreover, greater spending power makes 'getting wins' easier. -

Marx's Value Theory

I'll trust you on it. It makes sense that if an organisation wants to grow it needs to expand its revenue. -

Marx's Value Theory

I usually operate under the assumption that responses to a thread try to be on topic. Thing is, I can't tell because you never spend enough words detailing what you think. And every other time I've asked you for more words or clearer writing you ran away.

Think the observation is good. Some charities are in name only. I had in mind things like independent soup kitchens, urban foragers, food banks and volunteer teachers/counsellors. -

Marx's Value TheoryAnother thing to note is that the elementary form of value alone doesn't necessarily obey the following constraint:

V(x)=V(y) <=> xTy

With this assumption (and A->C) (1)->(5) can be derived.

(1) Assume xTy, then iff V(x) = V(y) and V(a)=V(b), iff V(x)+V(a)=V(y)+V(b), iff V(x+a)=V(y+b) iff (x+a)T(y+b)

(2) Assume xTy, then(Ax)T(Ay), then V(Ax)=V(Ay) so AV(x)=AV(y). Similarly AxTAy iff V(Ax)=V(Ay)=>V(x)=V(y)=>xTy

(3) Assume xTy, then (x-a)T(y-b) with aTb, then V(a)=V(b) and V(x-a)=V(y-b) then V(x)-V(a)=V(y)-V(b) so V(x)=V(y), reverse implications.

(4) xTy <=> V(x)=V(y) <=> yTx <=> V(y)=V(x)

(5) xTx <=> V(x)=V(x) -

Marx's Value TheorySubsubsection B: Quantitative determination of Relative value

This section largely consists of Marx specifying the algebraic structure that holds of the relative form.

Marx first summarises points he has made before:

Every commodity, whose value it is intended to express, is a useful object of given quantity, as 15 bushels of corn, or 100 lbs of coffee. And a given quantity of any commodity contains a definite quantity of human labour. The value form must therefore not only express value generally, but also value in definite quantity. Therefore, in the value relation of commodity A to commodity B, of the linen to the coat, not only is the latter, as value in general, made the equal in quality of the linen, but a definite quantity of coat (1 coat) is made the equivalent of a definite quantity (20 yards) of linen.

(1) Value only applies to use values.

(2)(a) The value form is partly what renders use values as commensurable products of human labour.

(b) The value form also gives use values their definite magnitudes of value.

The equation, 20 yards of linen = 1 coat, or 20 yards of linen are worth one coat, implies that the same quantity of value substance (congealed labour) is embodied in both; that the two commodities have each cost the same amount of labour of the same quantity of labour time. But the labour time necessary for the production of 20 yards of linen or 1 coat varies with every change in the productiveness of weaving or tailoring. We have now to consider the influence of such changes on the quantitative aspect of the relative expression of value.

It's pretty clear to see that, say, 1 pair of trousers has less value than 2 pairs of trousers, so Marx expands on the various operations that respect the 'is worth' relation T and the relationship between socially necessary labour time and value.

I. Let the value of the linen vary,[20] that of the coat remaining constant. If, say in consequence of the exhaustion of flax-growing soil, the labour time necessary for the production of the linen be doubled, the value of the linen will also be doubled. Instead of the equation, 20 yards of linen = 1 coat, we should have 20 yards of linen = 2 coats, since 1 coat would now contain only half the labour time embodied in 20 yards of linen. If, on the other hand, in consequence, say, of improved looms, this labour time be reduced by one-half, the value of the linen would fall by one-half. Consequently, we should have 20 yards of linen = ½ coat. The relative value of commodity A, i.e., its value expressed in commodity B, rises and falls directly as the value of A, the value of B being supposed constant

Summarising: value is proportional to socially necessary labour time. Assuming that the labour time for y does not change, this means that if the labour time for x increases, and we have xTy, the amount of y which x is worth increases. Inversely if the labour time for x decreases, the the amount of y which is worth x decreases.

Assume 'a x is worth b y', that x stands in the relative form to y which is its equivalent. Then: let V represent a commodity's value. If V(x) = V(y), then V(x) halves, we have 2V(x)=V(y). Inversely if V(x) doubles, we have V(x)=2V(y). As a consequence of the first, we have 2a x is worth b y. As a consequence of the second, we have a x is worth 2b y.

II. Let the value of the linen remain constant, while the value of the coat varies. If, under these circumstances, in consequence, for instance, of a poor crop of wool, the labour time necessary for the production of a coat becomes doubled, we have instead of 20 yards of linen = 1 coat, 20 yards of linen = ½ coat. If, on the other hand, the value of the coat sinks by one-half, then 20 yards of linen = 2 coats. Hence, if the value of commodity A remain constant, its relative value expressed in commodity B rises and falls inversely as the value of B.

This paragraph applies the same reasoning to the equivalent. Here we have V(x)=V(y) if V(y) halves, then V(x)=2V(y), if V(y) doubles, we have 2V(x)=V(y).

Marx notes that this comes down the the symmetry of T, that relative and equivalent forms depend solely on 'accidental position' in T:

If we compare the different cases in I and II, we see that the same change of magnitude in relative value may arise from totally opposite causes. Thus, the equation, 20 yards of linen = 1 coat, becomes 20 yards of linen = 2 coats, either, because the value of the linen has doubled, or because the value of the coat has fallen by one-half; and it becomes 20 yards of linen = ½ coat, either, because the value of the linen has fallen by one-half, or because the value of the coat has doubled.

then continues:

III. Let the quantities of labour time respectively necessary for the production of the linen and the coat vary simultaneously in the same direction and in the same proportion. In this case 20 yards of linen continue equal to 1 coat, however much their values may have altered. Their change of value is seen as soon as they are compared with a third commodity, whose value has remained constant. If the values of all commodities rose or fell simultaneously, and in the same proportion, their relative values would remain unaltered. Their real change of value would appear from the diminished or increased quantity of commodities produced in a given time.

If V(x)=V(y) and V(x) and V(y) are both doubled, then V(x)=V(y) still, only the relative values of x and y to other commodities change.

IV. The labour time respectively necessary for the production of the linen and the coat, and therefore the value of these commodities may simultaneously vary in the same direction, but at unequal rates or in opposite directions, or in other ways. The effect of all these possible different variations, on the relative value of a commodity, may be deduced from the results of I, II, and III.

IE, if V(x)=V(y) and V(x) is scaled by a/b, aV(x)=bV(y).

Focussing in on point III, Marx adds:

Thus real changes in the magnitude of value are neither unequivocally nor exhaustively reflected in their relative expression, that is, in the equation expressing the magnitude of relative value. The relative value of a commodity may vary, although its value remains constant. Its relative value may remain constant, although its value varies; and finally, simultaneous variations in the magnitude of value and in that of its relative expression by no means necessarily correspond in amount.[21]

(1) The relative value of x to y doesn't completely characterise the value of x.

(2) Changes in the relative value of x to y don't completely characterise changes in value more generally.

(3) x can remain worth y even under incredibly chaotic conditions of exchange.

The incompletion of this value form, and its reference to the values of other commodities not in 'x is worth y' prefigure later stages of the account; the expanded/total and money forms of value.

Summarising the properties of V we will have that:

(A) V(x+y)=V(x)+V(y)

(B) V(Ax)=AV(x)

(C) V(x-y)=V(x)-V(y)

incidentally from (3) we have that V(0)=V(x-x)=V(x)-V(x)=0. Nothing is worth nothing. Note that these correspond neatly to the algebra of commodities I set up already:

Where x,y,a,b are commodities in the sense I developed here, and A is a number which respects the amount structure of x and y.

(1) V(x+y)=V(x)+V(y) <=> [xTy & aTb => (x+a)T(y+b)]

(2) V(Ax)=AV(x) <=> [xTy <=> (Ax)T(Ax)]

(3) V(x-y)=V(x)-V(y) <=> [xTy <=> (x-a)T(y-a)]

(4) [V(x)=V(y) <=> V(y)=V(x) ]<=> T is symmetric.

(5) V(x)=V(x) <=> T is reflexive.

V(x) should be seen as taking values in with the continuous amount structure. That is:

and properties A,B,C establish that it's a homomorphism. Note that it is a surjective homomorphism because V(x) and V(y) can be the same without x=y. This is just to say that different amounts of different commodities can still be worth the same.

Also, this isn't yet an ordered field because there are no negative values - developing those will come later when dealing with debt and money of account. -

Marx's Value TheorySubsection summary: the relative form of value, nature and import of this form.

If x use value 1 is worth y use value 2, x use value 1 stands in the relative form of value to y use value 2 which is the equivalent. use value 2, when envisioned or actually put into this relation, becomes the value form of use value 1; the means of the representation of the value in 1. Prior to this, the two are rendered equivalent in their reduction to human labour in the abstract - as socially useful products of labour power -, and the (ratio of) socially necessary durations of the labour gives the magnitudes x and y. -

Marx's Value TheoryMarx continues linking value to labour:

There is, however, something else required beyond the expression of the specific character of the labour of which the value of the linen consists. Human labour power in motion, or human labour, creates value, but is not itself value. It becomes value only in its congealed state, when embodied in the form of some object. In order to express the value of the linen as a congelation of human labour, that value must be expressed as having objective existence, as being a something materially different from the linen itself, and yet a something common to the linen and all other commodities. The problem is already solved.

Mostly repeating things I've already written about. He does however draw attention to a distinction: labour is not value, labour creates value. Labour becomes value only when a commodity is worked on and enters, even figuratively, into an exchange relation with other commodities. The 'congealed state' of labour in the commodity is aligned with its value; and the (socially necessary) duration of that labour imbues that commodity's with value of a given magnitude.

When occupying the position of equivalent in the equation of value, the coat ranks qualitatively as the equal of the linen, as something of the same kind, because it is value. In this position it is a thing in which we see nothing but value, or whose palpable bodily form represents value. Yet the coat itself, the body of the commodity, coat, is a mere use value. A coat as such no more tells us it is value, than does the first piece of linen we take hold of. This shows that when placed in value-relation to the linen, the coat signifies more than when out of that relation, just as many a man strutting about in a gorgeous uniform counts for more than when in mufti.

Again, restating that when a commodity takes a position in the elementary form of value; as either in the relative or equivalent form; only its value is highlighted - all properties irrelevant to this are filtered out.

In the production of the coat, human labour power, in the shape of tailoring, must have been actually expended. Human labour is therefore accumulated in it. In this aspect the coat is a depository of value, but though worn to a thread, it does not let this fact show through. And as equivalent of the linen in the value equation, it exists under this aspect alone, counts therefore as embodied value, as a body that is value. A, for instance, cannot be “your majesty” to B, unless at the same time majesty in B’s eyes assumes the bodily form of A, and, what is more, with every new father of the people, changes its features, hair, and many other things besides.

As before, the physical body of the commodity is subject to a sortal; it counts as its value alone and everything else is filtered out.

Hence, in the value equation, in which the coat is the equivalent of the linen, the coat officiates as the form of value. The value of the commodity linen is expressed by the bodily form of the commodity coat, the value of one by the use value of the other. As a use value, the linen is something palpably different from the coat; as value, it is the same as the coat, and now has the appearance of a coat. Thus the linen acquires a value form different from its physical form. The fact that it is value, is made manifest by its equality with the coat, just as the sheep’s nature of a Christian is shown in his resemblance to the Lamb of God.

If 1 pair of trousers is worth 1 coat, 'coat' serves as the representation of value for the trousers, with a magnitude '1' and ratio to 'pair of trousers' as 1:1. The bodily form of the coat counts as the value of the pair of trousers, thus the trousers become a representation of the value embodied in the coat. More generally, 'x use value 1 is worth y use value 2' has the same structure. Note that only use values can serve as repositories of value.

Marx summarises:

We see, then, all that our analysis of the value of commodities has already told us, is told us by the linen itself, so soon as it comes into communication with another commodity, the coat. Only it betrays its thoughts in that language with which alone it is familiar, the language of commodities. In order to tell us that its own value is created by labour in its abstract character of human labour, it says that the coat, in so far as it is worth as much as the linen, and therefore is value, consists of the same labour as the linen. In order to inform us that its sublime reality as value is not the same as its buckram body, it says that value has the appearance of a coat, and consequently that so far as the linen is value, it and the coat are as like as two peas. We may here remark, that the language of commodities has, besides Hebrew, many other more or less correct dialects. The German “Wertsein,” to be worth, for instance, expresses in a less striking manner than the Romance verbs “valere,” “valer,” “valoir,” that the equating of commodity B to commodity A, is commodity A’s own mode of expressing its value. Paris vaut bien une messe. [Paris is certainly worth a mass]

and concludes the subsection:

By means, therefore, of the value-relation expressed in our equation, the bodily form of commodity B becomes the value form of commodity A, or the body of commodity B acts as a mirror to the value of commodity A.[19] By putting itself in relation with commodity B, as value in propriâ personâ, as the matter of which human labour is made up, the commodity A converts the value in use, B, into the substance in which to express its, A’s, own value. The value of A, thus expressed in the use value of B, has taken the form of relative value. -

BanningsIf you're talking about gurugeorge, , he was advancing a white ethnostate and the inferiority of blacks. Like anyone who knows how bad this looks, he used a slimy catalogue of euphemisms to make the point. He was warned repeatedly to stop expressing racist views on the forum and ask to denounce Naziism personally; he did neither. Surely the bar should be set higher than that.

-

Unjust Salvation System?More on salvation from @tenderfoot, merging from 'Possibility of Obtaining Salvation after Death'

I would love to hear some thoughts on the necessity of obtaining salvation after death for the compatibility of Hell with a maximally good God and human free will!

Continuing off the arguments of previous posts that salvation, based on reformed, double predestination doctrine presents a view of Hell that is incompatible with a good, loving God,

My argument is as follows:

1. The Christian God is maximally good and loving.

2. If God’s salvation exists, either humans have a degree of choice in their salvation or their eternity has been predestined by God

3. If eternity is predetermined by God, some people have been damned to Hell irrespective of their lives and choices on Earth

4. Damning people to Hell (such that they could not have avoided it) is evil

5. Therefore, predestination is evil.

6. Therefore, either salvation is evil, or humans have a degree of choice in their salvation.

To protect salvation and maintain an all-good God who has created salvation for all who may accept it, it seems necessary that all human beings have a real chance to know of God’s existence and choose God. As the nature of our world is, there are certainly people who never learn about the Christian God or doctrine of salvation before their death (see comment https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/217169)

I would like to argue for the existence of some “step” after one’s life on Earth and before Heaven/ Hell in which all human beings have the opportunity to choose Jesus as their Lord. If there is a chance to choose God after death, then salvation is not evil and God in fact it is maximally good, just, and merciful (because eternal communion with God is offered to all who may choose it!) This maintains human free will and the choice to love God (it is not compulsory) while still allowing those who seek goodness in this world to find the omnibenevolent God, regardless of their knowledge of Him in the physical, temporal world. Without this step, I don’t see a way to reconcile the unequal access to God on this Earth with eternal damnation. If that were the case, it seems that salvation is tinged with evil in a way humans cannot defend without appealing to “God’s plan being too wonderful to understand.”

I would love to hear some feedback on this! :)

fdrake

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2025 The Philosophy Forum