-

The Christian narrativeAs a matter of fact, ‘person’ was derived from ‘personae’, the masks worn by actors in Greek drama. Regardless, surely Christians of any school or sect must recognize the distinction between persons and things must they not?

-

The Christian narrativeThank you for the explanation, I see your point.

But surely describing the persons of the Trinity as ‘things’ is even greater error than was mine. -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding beingIt just occurred to me spontaneously - don't want to make too much of it.

-

The Question of CausationWell, of course. But what did you mean, then, by 'accepting our true nature as primates'? In what way is that being denied, and how would acknowledging it rectify that?

-

The Christian narrativeOne could also engage in a conversation about what, precisely, is the error, but then, it's a lot easier to make snide remarks, isn't it.

-

The Question of CausationI expect we'll all just continue acting like the social primates that we are, despite efforts on the part of many to deny our nature. ...

To me it seems likely that improved and more widespread knowledge of our natures is the best hope humanity has for avoiding the bleakness that the denial of our natures is leading towards. — wonderer1

There's a real problem with the naturalist account of human nature, which is that it doesn't or can't acknowledge the sense in which we're essentially different from other animals. Considerable weight is given to demonstrations of rudimentary reasoning skills by caledonian crows and chimps to press home this point. See? We're just like them! I think we take comfort in the kind of 'one-with-nature' aspect of evolutionary naturalism. But it also gets us off the hook of recognising that we're 'the symbolic species', as Terrence Deacon put it in a book of that name, with capacities and possibilities and also existential plights which they will never have.

But neither evolutionary naturalism nor scientific realism provide us with the moral resources necessary to cope with the human condition. The criteria of biological evolution aren't necessarily meaningful in a context as utterly removed from the natural state. But as many have commented, Darwinian naturalism dovetails nicely with myths of progress and capitalist economics. And with the prestige of science.

Unlike the other primates, we have concepts of nature, we sense ourselves as being different from it in ways they cannot. Acknowledgement of that has to be a part of philosophy, but it's not something inherent within naturalism. -

Idealism in ContextIn fact, I think that Many Worlds is actually very coherent. Its fault is not intelligibility but that its just radically strange. Qbists and relationalist views are much more incoherent imo. — Apustimelogist

I can see why. I'll leave the explanations of its shortcomings to Phillip Ball. -

The Christian narrativeAlthough looking at the original post again, it's plain the entire purpose is debunking Christianity, so I should have kept out of it, and will now.

-

The Christian narrativeSo when you've got nothing substantial to add, you'll try condescending or sarcasm or ad homs, right? Rather than actually trying to engage in a conversation? It does make me wonder if I should bother interacting with you.

Always sounded like a band name to me. -

Idealism in ContextIs matter, stripped of all the perceptible qualities and can only exist parasitically on other objects, a perceptible object? I understand by asking this, I am committing an error -- but please humor me. — L'éléphant

Right on point. Berkeley is objecting to the concept of matter as 'substance' in the philosophical sense - something which underlies the observable attributes, but which is separate to them. Recall that in the newly-emerging physics, and in John Locke, whom Berkeley was criticizing, the sharp distinction was made between primary attributes - quantitative, measurable and predictable mathematically - and how objects appear - color, scent, form, etc. So in that sense, 'matter' became an abstraction - something different from what appears to us. This is what I think Berkeley was protesting, but on purely empirical grounds. If all knowledge comes from experience - as Locke himself says - then how do we know this supposedly non-appearing, measurable 'stuff' we designate 'matter' actually exists?For Berkeley, that’s not empiricism, it’s speculation disguised as science.

Quite so! -

The Christian narrativeBut I think what I've said in the above posts acknowledges all of that. I said:

So two men both 'participate' in the form 'man' even though they are numerically different men. — Wayfarer

Although now I've read that entry of Timothy's, I understand better the signficance of the term 'participate'.

Mystics, not mysterians. Different things. -

The Christian narrativeI'm not Catholic, but I am trying to portray what I think they would say. The Count has been scarce the last few days but I acknowledge that he has far greater knowledge of this than I do.

Much of the confusion here seems the result of an over dependence on syllogistic logic, which cannot deal adequately with relations. — Banno

It occured to me after describing the 'both is and is not' meaning of the aphorism I quoted, that this communicates the sense in which the divine nature transcends logic. Aristotelian logic assumes the law of non-contradiction, which states that something cannot be both A and not A at the same time and in the same respect. In this perspective, paradoxes are flaws or errors.

However some religious teachings exhibit paradox not as a logical error, but as an insight to higher logic. The "both is and is not" language communicates that the subject is beyond the limitations of human reason. (I have encountered a scholarly article on Buddhist logic which echoes this, The Logic of the Diamond Sutra: A is not A, therefore it is A.)

'Foolishness to the Greeks', indeed. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)Trump's authoritarian takeover of the United States is proceeding very smoothly - and with hardly any dissent! Now he is sending in federal police to take over Washington DC and ship the homeless off to internment camps so as not to offend the residents. Hardly a murmur of dissent. The plan is being executed flawlessly.

-

Idealism in ContextI can't see how idealism is able to explain three things - or perhaps better, in offering explanations it admits that there are truths that are independent of mind and so ceases to be different to realism in any interesting way.

Novelty.

We are sometimes surprised by things that are unexpected. How is this possible if all that there is, is already in one’s mind?

Agreement .

You and I agree as to what is the case. How is that possible unless there is something external to us both on which to agree?

Error.

We sometimes are wrong about how things are. How can this be possible if there is not a way that things are, independent of what we believe? — Banno

Depends on how idealism is interpreted.

Transcendental idealism does not claim that the world is a mere figment of individual minds, but rather that the structure of experience is provided by our shared and inherent cognitive systems.

Novelty emerges from new external data interacting with our fixed frameworks. In Kant’s view, while the mind supplies the framework for experience, it must work in tandem with the manifold of sensory impressions. The unexpected quality of new data is what we call “novelty.” It doesn’t imply that the mind conjured it from nothing—it simply had to update its organization in response to an input that wasn’t fully anticipated. Phenonena that can't be accomodated in those pre-existing frameworks become anomalies - and science has plenty of those.

Error occurs when our interpretations fail to match that data. When someone holds a belief that is incorrect, it is because there's a mismatch between their mental constructs and what is going on. Although our experience is structured by the mind, it still emanates from an external world. A belief is in error when that mental structure misrepresents or fails to adequately capture the sensory data.

Agreement arises because we all operate with fundamentally similar mental structures. This preserves the objectivity of the external world while acknowledging the active role our minds play in organizing experience.

The way in which this differs from realism, is that it understands that there is an ineliminably subjective aspect of knowledge, meaning that the objective domain does not possess the inherent reality that is accorded it by scientific realism. -

Idealism in ContextOp is excellent. I wasn't going to enter into this conversation since it's stuff he and I have been over multiple times. — Banno

Thank you Banno, but the thrust of this particular OP is historical - something which nobody's picked up yet. It was actually motivated by a comment I read somewhere that scholastic philosophy was realist, and in no way compatible with later idealism. I thought there was something wrong about that comment, and researching that lead to this thread.

The key point I found was that scholastic (Aristotelian-Thomist) philosophy is realist concerning universals:

In this view, to know something is not simply to construct a mental representation of it, but to participate in its form — to take into oneself, immaterially, the essence of what the thing is. (Here one may discern an echo of that inward unity — a kind of at-one-ness between subject and object — that contemplative traditions across cultures have long sought, not through discursive analysis but through direct insight.) Such noetic insight, unlike sensory knowledge, disengages the form of the particular from its individuating material conditions, allowing the intellect to apprehend it in its universality. This process — abstraction— is not merely a mental filtering but a form of participatory knowing

This is completely different to what we mean by realism in today's philosophy, which is generally nominalist and propositional rather than perspectival.

It was the abandonment of the belief in universals that gave rise to the empiricism, nominalism, and scientific realism that characterises modernity - and the 'crisis of the European sciences' (Husserl). The sense of division or 'otherness' that pervades modern thought - the Cartesian anxiety, as Richard Bernstein expresses it.

So the argument is that Berkeley (and later, Kant) were aware of this disjunction or rupture, which is why they came along after the decline of Scholastic Realism. A-T didn't have to deal with this rupture, as for them, it didn't figure.

So this is not an argument for idealism- hence the title, Idealism in Context, meaning historical context.

(incidentally, this has lead me to the study of analytic Thomism, in particular Bernard Lonergan, who attempts to reconcile Aquinas and Kant. But that's for the future.) -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding beingRight - in those debates I had with Streetlight, he referred to Heidegger a few times. Since then, I've read a bit more and am *starting* to understand and appreciate Heidegger somewhat. Mastering the whole oeuvre is a challenge and, I regret, something I'll probably never accomplish, but I'm coming to appreciate parts of it.

The ‘I am’ , the self, does not pre-exist its relation to the world, but only exists in coming back to itself from the world. — Joshs

Why does this remind me of the Libet experiments? :chin: -

On emergence and consciousnessIf you wouldn’t mind, I’d like to hear what you believe ‘substance’ means.

— Wayfarer

A substance is something that objectively exists. — MoK

So does this substance called mind have a molecular structure? -

The Christian narrativeThe comment was in reference to the difference between numerical identity and two entities of the same kind. 'Essence' is 'what is essential to the being', from the Latin 'esse' 'to be'. So two men both 'participate' in the form 'man' even though they are numerically different men.

This also ties into the aphorism I quoted from Meister Eckhardt (whom we will recall was a 13th c Dominican friat and preacher whose sermons are still in print.)

God is your being, but you are not HIs

The rationale for this is that God is not a being, but Being. Therefore, our being or actual existence is not other than God - our ground or real nature is rooted in the divine. As Eckhardt said in one of his sermons, "The ground of my soul and the ground of God are one ground." This is the non-dualistic heart of his teaching.

"but you are not his [being]": we are a created entity (which is original meaning of 'creature'), an instance of Being, we ourselves are not God. So this is another illustration of 'both is and is not' that is seen in the Shield of Faith. So the God is the 'three persons' of the Trinity, but each of them is not God. -

Idealism in ContextWatch out 180, woo about! But fear not, the woo police will come to our rescue.

-

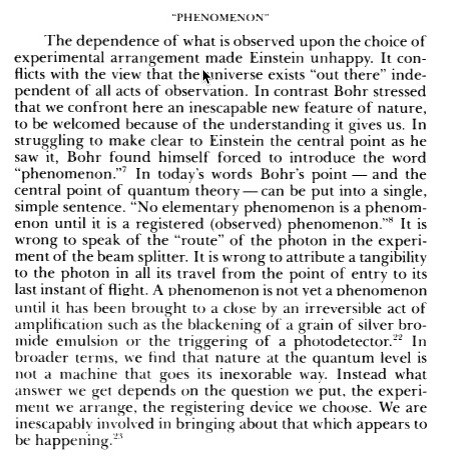

Idealism in ContextIt (Copenhagen Interpretation) may lack philosophical rigor — Gnomon

We should say something about the Copenhagen Interpretation. The name itself was coined by Heisenberg in the 1950’s, writing retrospectively about that period. It is not a scientific theory. It is a compendium of aphoristic expressions about what can and can’t be said on the basis of the observations of quantum physics. These were mostly based on discussions of the philosophical implications of quantum physics between the principles Bohr, Heisenberg, Pauli, Dirac and Born conducted pre WWII. Many of these aphorisms have passed into popular culture, such as:

What we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning. — Heisenberg

I think that modern physics has definitely decided in favor of Plato. In fact the smallest units of matter are not physical objects in the ordinary sense; they are forms, ideas which can be expressed unambiguously only in mathematical language. — Heisenberg, The Debate between Plato and Democritus

[T]he atoms or elementary particles themselves are not real; they form a world of potentialities or possibilities rather than one of things or facts. — Heisenberg

The last is what scientific realism can't accept. It forces the question on us, if the so-called fundamental particles only have potential or possible existence, then what is everything made from? Bohr expresses similar ideas:

Everything we call real is made of things that cannot be regarded as real. — Bohr

Those who are not shocked when they first come across quantum theory cannot possibly have understood it — Bohr

Physics is not about how the world is, it is about what we can say about the world — Bohr

Positivists have sometimes made the mistake of thinking that Bohr's attitude can be described as positivist, but in Heisenberg's Physics and Beyond, he is recorded as saying:

The positivists have a simple solution: the world must be divided into that which we can say clearly and the rest, which we had better pass over in silence. But can anyone conceive of a more pointless philosophy, seeing that what we can say clearly amounts to next to nothing? If we omitted all that is unclear, we would probably be left with completely uninteresting and trivial tautologies.

And presumably a large number of interminable debates about 'justified true belief' and the like.

But you can see how easily the ghost of Berkeley haunts this discussion. Hovers over their shoulders, so to speak. -

Idealism in ContextThefe are several coherent realist perspectives — Apustimelogist

I’m not alone in thinking that the many-worlds interpretation is wildly incoherent. I believe that Bohm’s pilot waves have been definitely disproven, but I’m not going to dig for it. Copenhagen and QBism are defended by reputable philosophers of science, and I’ve given plenty of reasons why I think they’re philosophically meaningful. Nothing to do with ‘echo chambers’ more that you can’t fathom how any anti-realist interpretation could possibly be meaningful.

This is why I think in another context (Berkeley) could have been something like a logical positivist. — Apustimelogist

He was an empiricist - ‘all knowledge arises from experience’. That is what he shares in common with positivism, but the conclusions he draws from it are radically different. But when he says he rejects the idea of physical substance, he means exactly that. Things really do exist as ideas in minds. And now we know that if you dissect a material object down to its most minute fundamental entities, then…

Speaking of positivism, there’s an anecdote in Werner Heisenberg’s book Physics and Beyond, an account of various conversations he had with Neils Bohr and others over the years. Members of the Vienna Circle visited Copenhagen to hear him lecture. They listened intently and applauded politely at the end, but when Bohr asked them if they had any questions, they demurred. Incredulous, he said ‘If you haven’t been shocked by quantum physics, then you haven’t understood it!’

Why, do you think?

Aristotle postulated a primitive definition of Energy (energeia) as the actualization of Potential. And modern physics has equated causal energy with knowledge (meaningful Information)*1*2. For which I coined the term EnFormAction : the power to transform. — Gnomon

Sorry not buying your schtick. It’s as if you put random encyclopedia entries in a blender.

Berkeley, like the logical positivists after him, failed to reconcile his philosophical commitment to a radical form of empiricism with his other philosophical commitment to agency and morality. But in his defence, nobody before or after Berkeley has managed to propose an ontology that doesn't have analogous issues. — sime

Should read ‘no empiricists before or after Berkeley…’ This is due to the inherent limitations of empiricism in dealing with what Kant describes as ‘the metaphysics of morals’. -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding beingI am impressed with your ideas and think you’re a valuable contributor to this Forum.

-

Idealism in ContextBut that’s the point of the OP! Aquinas was traditional (although for his day he was considered progressive.) But it was the beginning of secular modernism and the new ideas of empiricism that Berkeley was criticizing.

-

Idealism in ContextI think that terminology is certainly not his. Have a browse of the Early Modern Texts translation provided in Ref 1. He’s quite the sophist. (I recommend the Dialogues.)

-

Idealism in ContextIn Berkeley's expression "esse est percipi", I understand the word "perceive" to refer to something through one of the five senses, not to something understood in the mind. — RussellA

But, for Berkeley, all that is real are spirits, which could be glossed as ‘perceiving beings’, and objects are ideas in minds.

But I don’t think that the corollary of that is that non-perceived objects cease to exist. They exist in the sight of God. (Do you know the limerick?)

The problem is always that ‘mind’ is outside a Wheeler’s usual term of reference. But Andrei Linde doesn’t hesitate to speak about it. -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding beingIf you reconsider the foundation on which everything is built, won't it change the superstructure? — Astorre

My interest in philosophy grew from a spiritual quest (rather a quixotic one, hence the avatar). I pursued it through two degrees, one in Comparative Religion, the second in Buddhist Studies. There is a religious aspect to it, although 'religious' is probably too narrow a word. It is more like 'theosophical', (not referring to the Theosophical Society, but to the original 'small t' version.) Some of the experiences (or epiphanies) originating from those studies have had considerable influence on me, and I've been tracing them through various philosophers and schools. That change you’re referring to is ‘metanoia’, a transformation of perspective. -

ChatGPT 4 Answers Philosophical QuestionsHa! Fascinating topic (as is often the case with your posts.) Actually now you mention it, I did use Chat to explore on the topics here, namely, why rural America has shifted so far to the Right in the last few generations. Gave me an excellent list of readings.

-

Idealism in ContextI take measurement and observation to be observer-dependent. I mean, you could infer that many similar processes might be taking place without an observer, but you'd have to observe them to find out ;-)

-

ChatGPT 4 Answers Philosophical Questionsmaybe you're right. I'm a pretty diehard Never Trumper and the few times I asked Gemini about Trump-related issues I got that kind of response but it was early days, and I haven't really pursued it since. After all there's not exactly a shortage of news coverage about US politics.

-

Idealism in ContextTwo meanings of ‘representation’ in play there. He objects to representative realism but I’m sure he would accept that the sight of smoke represents fire or a dangerous animal represents a threat.

-

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding beingPerfect! I had many debates on this forum in years past, on account of my claim that the noun 'ontology' is derived from the first-person participle of the Greek verb 'to be' (which is, of course, 'I AM'). Accordingly, I argued that ontology was, properly speaking, concerned with the nature of being (literally, 'I am-ness') rather than of 'what exists'. This distinction I held to be an example of what I considered fundamental to the proper distinction of 'being' from 'existence', which is hardly recognised by modern philosophers. I was told that my definition was 'eccentric' and completely mistaken. Finally, I was sent a link to a paper I mentioned to you before, 'The Greek Verb 'To Be' and the Problem of Being' , Charles Kahn, whom I was told was an authority on the subject. But I learned that rather than challenging my claim, this paper actually supported it, through passages such as:

[Parmenides] initial thesis, that the path of truth, conviction, and knowledge is the path of "what is" or "that it is" (hos esti) can then be understood as a claim that knowledge, true belief, and true statements, are all inseperably linked to "what is so" - - not merely to what exists, but what is the case (emphasis in original).

--[The] intrinsically stable and lasting character of Being in Greek - - which makes it so appropriate as an object of knowing and the correlative of truth - - distinguishes it in a radical way from our modern notion of existence. — Charles H. Kahn

Finally, this conceptual divergence was definitively cemented in early Christian theology — Astorre

hence Heidegger's critique of 'onto-theology', the 'objectification' of the being. While the basic fact of the matter is that Being is an act, not a thing. (Something that is hardly news to Buddhists.)

Glad to have someone contribute who now recognises this distinction! :pray:

@Jamal -

The Question of CausationThis is precisely why I favour Husserl's approach to a science of consciousness. — I like sushi

Pleased to find we have this in common. -

The Christian narrativeAre you familiar with the amazing feats of Matteo Ricci in China? Who, on the occasion of his return to Europe, was hosted at an Imperial Banquet, at which, when toasted, he stood and extemporised Chinese poetry as a gesture of gratitude? Or Ippolito Desideri who made it to Lhasa in 1716 and mastered Tibetan? Both amazing men. Anyway, side issue. But more than one Jesuit has thoroughly impressed me.

-

Idealism in ContextThe quoted passage just shows that Penrose is not a rigid determinist, — Janus

I understand that Roger Penrose is not a materialist — if anything, he leans toward mathematical Platonism. But like Einstein, he is staunchly realist: they both believe that the world just is a certain way, and that the task of physics is to discover what that way is. Neither can reconcile themselves to the fundamentally stochastic character of quantum physics, nor to the philosophical implications of the uncertainty principle, which seem to undercut their conviction that nature has a definite, determinate structure. Einstein once remarked that if quantum theory were correct, he would have trouble saying what physics was even about any more.

Consider two of the better popular accounts of this dispute: Quantum: Einstein, Bohr, and the Great Debate about the Nature of Reality by Manjit Kumar, and Uncertainty: Einstein, Heisenberg, Bohr, and the Struggle for the Soul of Science by David Lindley. The “great debate” in the first title and the “struggle for the soul of science” in the second are, at root, the same battle — a battle over objectivity. Can physics provide, and should it aim to provide, a truly objective account of the world? Realism tends to treat this as a yes-or-no question. And that’s where, I think, the problem lies.

John Wheeler, 'Law without Law'

Which all stands to reason, by the way, because after all 'phenomenon' means 'what appears'. -

Idealism in ContextWell, yeah, but how do you take issue with a direct quotation? :brow:

The passage you quote has nothing to do with the topic at hand. That is a precis of his book Emperor's New Mind. Separate topic. -

The Christian narrativeFirst, God is everything so we are ultimately somewhere in The One, and second, I, for a time, am NOT God and he is not me — Fire Ologist

A quote attributed to Meister Eckhart: ‘God is your being, but you are not His’.

They’d have to be Jesuit :lol:

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum