-

Apustimelogist

946

Apustimelogist

946

Not really sure what this is trying to convey. Thefe are several coherent realist perspectives on QM which don't invoke any form of collapse, such as Bohmian, Many Worlds, Stochastic mechanics and possibly others. Your response just seems to me like someone pretending that these theories, which all reproduce the correct quantum behavior, don't exist. You have clearly put yourself in an echo chamber where the only relevamt opinions on QM are those of subjectivists, wooists, relationalists.

But IMO he used the empiricists' arguments (e.g. Locke) — boundless

Berkeley IMO took away the 'physical' using empiricist arguments. — boundless

This is why I think in another context he could have been something like a logical positivist. I just get the impression even from wikipedia that despite being clearly a hardcore apologist of God, he had a mindset and reasonings in common with the analytical tradition, imo. -

180 Proof

16.5k

180 Proof

16.5k

:100:↪Wayfarer

Not really sure what this is trying to convey. The[re] are several coherent realist perspectives on QM which don't invoke any form of collapse, such as Bohmian, Many Worlds, Stochastic mechanics and possibly others. Your response just seems to me like someone pretending that these theories, which all reproduce the correct quantum behavior, don't exist. You have clearly put yourself in an echo chamber where the only releva[nt] opinions on QM are those of subjectivists, wooists, relationalists. — Apustimelogist -

sime

1.2kBerkeley presented what we might now call a nominalist or deflationary view with respect to abstracta, both mathematical and physical, that considers talk about abstracta as reducing to talk about first personal observation criteria, and in this respect he preceded the thoughts of the logical positivist Ernst Mach, whom he likely inspired, approximately two centuries earlier. But he clearly ran into difficulties when it came to reconciling his radically empirical "esse is percipi" principle with rationalistic princples, especially

sime

1.2kBerkeley presented what we might now call a nominalist or deflationary view with respect to abstracta, both mathematical and physical, that considers talk about abstracta as reducing to talk about first personal observation criteria, and in this respect he preceded the thoughts of the logical positivist Ernst Mach, whom he likely inspired, approximately two centuries earlier. But he clearly ran into difficulties when it came to reconciling his radically empirical "esse is percipi" principle with rationalistic princples, especially

1) Rationalist principles pertaining to causal agency. Perception is usually understood to be passive, in contrast to agency that is neither passive nor directly perceived; so does agency exist, and if so then on what grounds, and how does causal agency relate to his perception principle?

2) The apparent reliablity of the principle of induction: How can the apparent reliability of inductive beliefs, which assume that the world will not to change radically from one observation to the next, be believed, if things only exist when observed?

Berkeley, like the logical positivists after him, failed to reconcile his philosophical commitment to a radical form of empiricism with his other philosophical commitment to agency and morality. But in his defence, nobody before or after Berkeley has managed to propose an ontology that doesn't have analogous issues. Indeed, the impersonal forces of nature posited by classical materialism that are forever only indirectly observable, seem to be a heady mixture of Berkeleyian spirits and Berkeleyian ideas upon closer examination, rather than being the anti-thesis of his position as commonly assumed.

. -

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

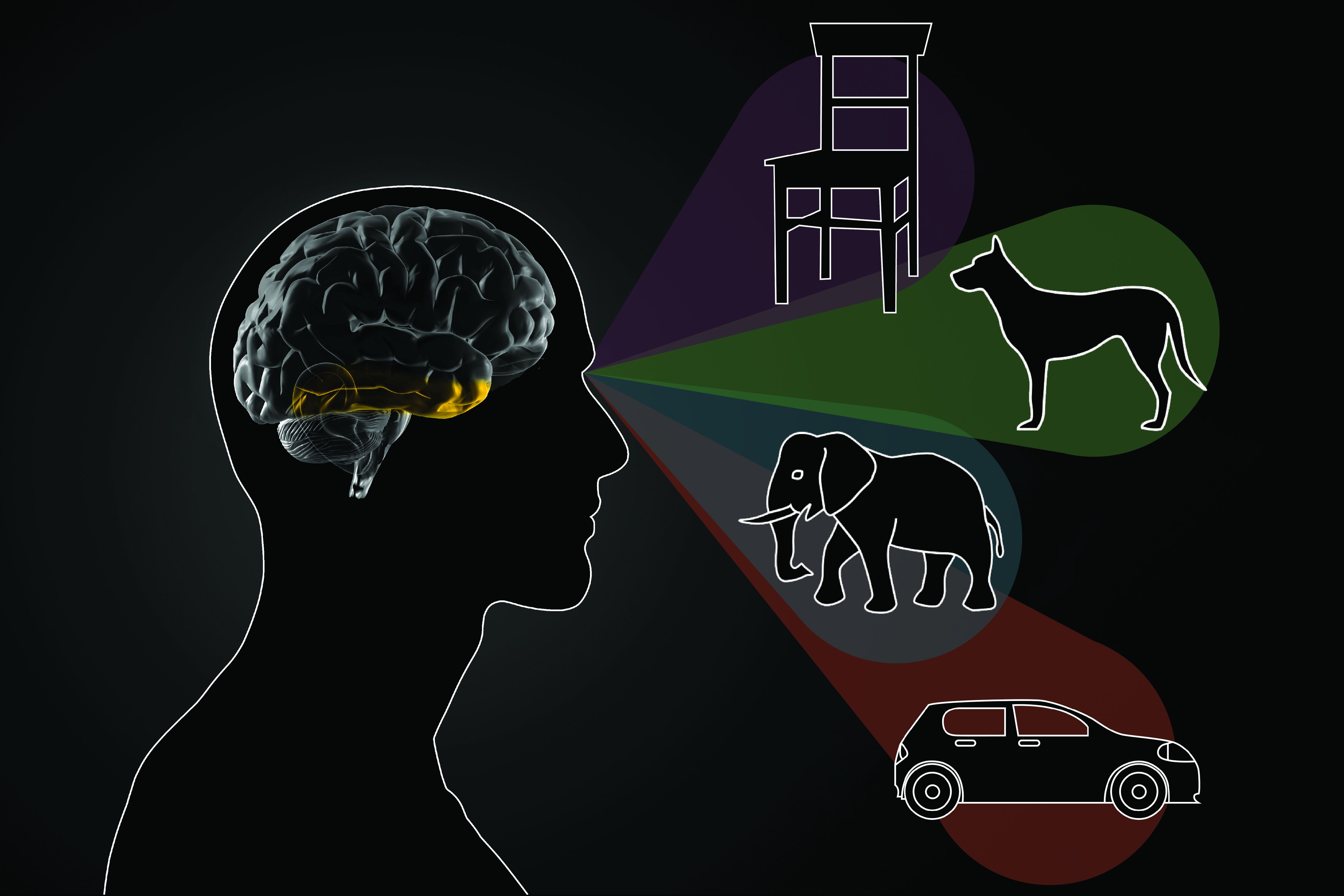

Aristotle postulated a primitive definition of Energy (energeia) as the actualization of Potential. And modern physics has equated causal energy with knowledge (meaningful Information)*1*2. For which I coined the term EnFormAction : the power to transform. Until now, I hadn't thought of that transformation from potential to actual as participation*3 in the Platonic form of an object : the importation of some property/qualia into oneself.In this view, to know something is not simply to construct a mental representation of it, but to participate in its form — to take into oneself, immaterially, the essence of what the thing is. — Wayfarer

Example : A photon --- atom of energy --- somehow picks up information about an apple as it reflects off the surface. When that photon is absorbed by a receptor in the retina, the colorless energy is converted into electrical signals that the brain can interpret (meaning) as redness. So you could say that the brain/mind*4 has been informed of a quality of appleness. The image in the brain or meaning in mind is not a chunk of apple matter, but a "bit" of appleness : the essence of a round red fruit out there in the real world.

If Aristotle was correct, a free photon (kinetic energy) is not yet a carrier, but a Potential for conveying Energy/Information from one place to another. . . . from matter to mind. Hence, our sponge-like minds are continually soaking-up essences from the material world : participating in its existence.??? :nerd:

*1. Information is Energy :

This book defines a dynamic concept of information that results in a conservation of information principle. . . . . conservation of energy . . .

https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-658-40862-6

*2. Information as a basic property of the universe :

A theory is proposed which considers information to be a basic property of the universe the way matter and energy are.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8734520/

*3. Participation : "participation" means the act or state of sharing, partaking, or receiving a part of something.

The "part" in question is what philosophers call Essence, or Qualia.

*4. Brain/Mind is a system ; brain is structure ; mind is function

-

Wayfarer

26.2kThefe are several coherent realist perspectives — Apustimelogist

Wayfarer

26.2kThefe are several coherent realist perspectives — Apustimelogist

I’m not alone in thinking that the many-worlds interpretation is wildly incoherent. I believe that Bohm’s pilot waves have been definitely disproven, but I’m not going to dig for it. Copenhagen and QBism are defended by reputable philosophers of science, and I’ve given plenty of reasons why I think they’re philosophically meaningful. Nothing to do with ‘echo chambers’ more that you can’t fathom how any anti-realist interpretation could possibly be meaningful.

This is why I think in another context (Berkeley) could have been something like a logical positivist. — Apustimelogist

He was an empiricist - ‘all knowledge arises from experience’. That is what he shares in common with positivism, but the conclusions he draws from it are radically different. But when he says he rejects the idea of physical substance, he means exactly that. Things really do exist as ideas in minds. And now we know that if you dissect a material object down to its most minute fundamental entities, then…

Speaking of positivism, there’s an anecdote in Werner Heisenberg’s book Physics and Beyond, an account of various conversations he had with Neils Bohr and others over the years. Members of the Vienna Circle visited Copenhagen to hear him lecture. They listened intently and applauded politely at the end, but when Bohr asked them if they had any questions, they demurred. Incredulous, he said ‘If you haven’t been shocked by quantum physics, then you haven’t understood it!’

Why, do you think?

Aristotle postulated a primitive definition of Energy (energeia) as the actualization of Potential. And modern physics has equated causal energy with knowledge (meaningful Information)*1*2. For which I coined the term EnFormAction : the power to transform. — Gnomon

Sorry not buying your schtick. It’s as if you put random encyclopedia entries in a blender.

Berkeley, like the logical positivists after him, failed to reconcile his philosophical commitment to a radical form of empiricism with his other philosophical commitment to agency and morality. But in his defence, nobody before or after Berkeley has managed to propose an ontology that doesn't have analogous issues. — sime

Should read ‘no empiricists before or after Berkeley…’ This is due to the inherent limitations of empiricism in dealing with what Kant describes as ‘the metaphysics of morals’. -

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

I'm sure that is aware of those other scientific "perspectives"*1 --- or interpretations --- which postulate something like a parallel reality that is "not directly observable" : hence not empirical. But among Philosophers, the Copenhagen version*2 may be the most popular*3 --- if that matters to anyone. It may lack philosophical rigor, and due to inherent Uncertainty, a single coherent explanation, but it is a fertile field for philosophical exploration.Not really sure what this is trying to convey. Thefe are several coherent realist perspectives on QM which don't invoke any form of collapse, such as Bohmian, Many Worlds, Stochastic mechanics and possibly others — Apustimelogist

For hypothetical scientific purposes, one or more of those alternative perspectives may better suit a materialist frame of mind*3. But, on a philosophical forum, and for philosophical purposes (introspecting the human mind), some form of Idealism, with a 2500 year history, may be more appropriate. BTW, even Bohm's*4 "realistic perspective" is typically labeled as a form of Idealism. :smile:

*1. Realist perspectives on quantum mechanics generally assert that quantum phenomena reflect an underlying reality, even if that reality is not directly observable or fully understood. This contrasts with interpretations that view quantum mechanics as purely a tool for prediction or a description of our knowledge rather than a reflection of objective reality.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=realist+perspectives+on+quantum+mechanics

*2. The Copenhagen interpretation is widely accepted as a foundational framework for understanding quantum mechanics, though it's not universally embraced. It's often the first interpretation presented in textbooks and forms the basis for much of the standard quantum mechanics curriculum. However, it's not without its critics, and alternative interpretations like the Many-Worlds interpretation or pilot-wave theories exist and have their proponents.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=copenhagen+interpretation+is+accepted

*3. Physicists still divided about quantum world, 100 years on :

More than a third -- 36 percent -- of the respondents favoured the mostly widely accepted theory, known as the Copenhagen interpretation.

https://www.nbcrightnow.com/national/physicists-still-divided-about-quantum-world-100-years-on/article_af1d9414-7a94-5378-88fa-1c0f40dacdad.html

*4. David Bohm's philosophical perspective, often termed "Bohmian idealism," posits a unified, interconnected reality where consciousness and the physical world are not separate but rather different expressions of a deeper, underlying order.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=bohm+idealism -

Wayfarer

26.2kIt (Copenhagen Interpretation) may lack philosophical rigor — Gnomon

Wayfarer

26.2kIt (Copenhagen Interpretation) may lack philosophical rigor — Gnomon

We should say something about the Copenhagen Interpretation. The name itself was coined by Heisenberg in the 1950’s, writing retrospectively about that period. It is not a scientific theory. It is a compendium of aphoristic expressions about what can and can’t be said on the basis of the observations of quantum physics. These were mostly based on discussions of the philosophical implications of quantum physics between the principles Bohr, Heisenberg, Pauli, Dirac and Born conducted pre WWII. Many of these aphorisms have passed into popular culture, such as:

What we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning. — Heisenberg

I think that modern physics has definitely decided in favor of Plato. In fact the smallest units of matter are not physical objects in the ordinary sense; they are forms, ideas which can be expressed unambiguously only in mathematical language. — Heisenberg, The Debate between Plato and Democritus

[T]he atoms or elementary particles themselves are not real; they form a world of potentialities or possibilities rather than one of things or facts. — Heisenberg

The last is what scientific realism can't accept. It forces the question on us, if the so-called fundamental particles only have potential or possible existence, then what is everything made from? Bohr expresses similar ideas:

Everything we call real is made of things that cannot be regarded as real. — Bohr

Those who are not shocked when they first come across quantum theory cannot possibly have understood it — Bohr

Physics is not about how the world is, it is about what we can say about the world — Bohr

Positivists have sometimes made the mistake of thinking that Bohr's attitude can be described as positivist, but in Heisenberg's Physics and Beyond, he is recorded as saying:

The positivists have a simple solution: the world must be divided into that which we can say clearly and the rest, which we had better pass over in silence. But can anyone conceive of a more pointless philosophy, seeing that what we can say clearly amounts to next to nothing? If we omitted all that is unclear, we would probably be left with completely uninteresting and trivial tautologies.

And presumably a large number of interminable debates about 'justified true belief' and the like.

But you can see how easily the ghost of Berkeley haunts this discussion. Hovers over their shoulders, so to speak. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

's Op is excellent. I wasn't going to enter into this conversation since it's stuff he and I have been over multiple times.

I can't see how idealism is able to explain three things - or perhaps better, in offering explanations it admits that there are truths that are independent of mind and so ceases to be different to realism in any interesting way.

Novelty.

We are sometimes surprised by things that are unexpected. How is this possible if all that there is, is already in one’s mind?

Agreement .

You and I agree as to what is the case. How is that possible unless there is something external to us both on which to agree?

Error.

We sometimes are wrong about how things are. How can this be possible if there is not a way that things are, independent of what we believe?

But moreover I reject the idealism/realism dichotomy, and the notion of "real" at work here.

I think Way takes a leap too far. He's welcome to do so, I won't be joining him. -

Wayfarer

26.2kOp is excellent. I wasn't going to enter into this conversation since it's stuff he and I have been over multiple times. — Banno

Wayfarer

26.2kOp is excellent. I wasn't going to enter into this conversation since it's stuff he and I have been over multiple times. — Banno

Thank you Banno, but the thrust of this particular OP is historical - something which nobody's picked up yet. It was actually motivated by a comment I read somewhere that scholastic philosophy was realist, and in no way compatible with later idealism. I thought there was something wrong about that comment, and researching that lead to this thread.

The key point I found was that scholastic (Aristotelian-Thomist) philosophy is realist concerning universals:

In this view, to know something is not simply to construct a mental representation of it, but to participate in its form — to take into oneself, immaterially, the essence of what the thing is. (Here one may discern an echo of that inward unity — a kind of at-one-ness between subject and object — that contemplative traditions across cultures have long sought, not through discursive analysis but through direct insight.) Such noetic insight, unlike sensory knowledge, disengages the form of the particular from its individuating material conditions, allowing the intellect to apprehend it in its universality. This process — abstraction— is not merely a mental filtering but a form of participatory knowing

This is completely different to what we mean by realism in today's philosophy, which is generally nominalist and propositional rather than perspectival.

It was the abandonment of the belief in universals that gave rise to the empiricism, nominalism, and scientific realism that characterises modernity - and the 'crisis of the European sciences' (Husserl). The sense of division or 'otherness' that pervades modern thought - the Cartesian anxiety, as Richard Bernstein expresses it.

So the argument is that Berkeley (and later, Kant) were aware of this disjunction or rupture, which is why they came along after the decline of Scholastic Realism. A-T didn't have to deal with this rupture, as for them, it didn't figure.

So this is not an argument for idealism- hence the title, Idealism in Context, meaning historical context.

(incidentally, this has lead me to the study of analytic Thomism, in particular Bernard Lonergan, who attempts to reconcile Aquinas and Kant. But that's for the future.) -

Wayfarer

26.2kI can't see how idealism is able to explain three things - or perhaps better, in offering explanations it admits that there are truths that are independent of mind and so ceases to be different to realism in any interesting way.

Wayfarer

26.2kI can't see how idealism is able to explain three things - or perhaps better, in offering explanations it admits that there are truths that are independent of mind and so ceases to be different to realism in any interesting way.

Novelty.

We are sometimes surprised by things that are unexpected. How is this possible if all that there is, is already in one’s mind?

Agreement .

You and I agree as to what is the case. How is that possible unless there is something external to us both on which to agree?

Error.

We sometimes are wrong about how things are. How can this be possible if there is not a way that things are, independent of what we believe? — Banno

Depends on how idealism is interpreted.

Transcendental idealism does not claim that the world is a mere figment of individual minds, but rather that the structure of experience is provided by our shared and inherent cognitive systems.

Novelty emerges from new external data interacting with our fixed frameworks. In Kant’s view, while the mind supplies the framework for experience, it must work in tandem with the manifold of sensory impressions. The unexpected quality of new data is what we call “novelty.” It doesn’t imply that the mind conjured it from nothing—it simply had to update its organization in response to an input that wasn’t fully anticipated. Phenonena that can't be accomodated in those pre-existing frameworks become anomalies - and science has plenty of those.

Error occurs when our interpretations fail to match that data. When someone holds a belief that is incorrect, it is because there's a mismatch between their mental constructs and what is going on. Although our experience is structured by the mind, it still emanates from an external world. A belief is in error when that mental structure misrepresents or fails to adequately capture the sensory data.

Agreement arises because we all operate with fundamentally similar mental structures. This preserves the objectivity of the external world while acknowledging the active role our minds play in organizing experience.

The way in which this differs from realism, is that it understands that there is an ineliminably subjective aspect of knowledge, meaning that the objective domain does not possess the inherent reality that is accorded it by scientific realism. -

Janus

18kBerkeleyan idealism consists in claiming not that the objects of the senses find their genesis in the individual human mind but in the mind of God, so the problems you enumerated don't seem to be relevant.

Janus

18kBerkeleyan idealism consists in claiming not that the objects of the senses find their genesis in the individual human mind but in the mind of God, so the problems you enumerated don't seem to be relevant.

The way I see it, the fact that we all experience the same world can be explained only by a collective mind we all participate in or an independently existing material world. We cannot know which alternative is true, the best we can do is decide which seems the more plausible. -

180 Proof

16.5k

180 Proof

16.5k

Yes, I agree, if only because it makes no sense to conceive of "mind" itself as merely "mind-dependent" (or in Berkeley's sense as "perceived"). Exception: "the mind of God"? – imo an unwarranted, even incoherent, assumption.I reject the idealism/realism dichotomy — Banno

:up: :up:The way I see it, the fact that we all experience the same world can be explained only by a collective mind we all participate in or an independently existing material world. We cannot know which alternative is true, the best we can do is decide which seems the more plausible. — Janus -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

Sure. I enjoyed the OP. As a bit of history it's not problematic...the thrust of this particular OP is historical — Wayfarer

The whole framing here is problematic. It presumes a subject/object dichotomy, then concludes that there are subjects. Hardly a surprise. Your answer to the problems of novelty, error an agreement presume there is something other than the mental against which our ideas stand. And despite it's popularity hereabouts, there are good reasons that philosophy moved past Thomism.

The explanation on offer, "god did it", can account for anything, and so accounts for nothing. Not what I look for in an explanation.

I find it hard to make sense of "collective mind".

I wan't going to do this. Damn. -

Janus

18kTranscendental idealism does not claim that the world is a mere figment of individual minds, but rather that the structure of experience is provided by our shared and inherent cognitive systems. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kTranscendental idealism does not claim that the world is a mere figment of individual minds, but rather that the structure of experience is provided by our shared and inherent cognitive systems. — Wayfarer

With no input from the structure of the world or a collective originating mind? That just doesn't compute.

Agreement arises because we all operate with fundamentally similar mental structures. This preserves the objectivity of the external world while acknowledging the active role our minds play in organizing experience. — Wayfarer

Not sufficient to explain the commonality of experience. That's why Kant says there are things in themselves which appear to us phenomena. Schopenhauer disagreed and claimed there cannot be things in themselves if there is no space and time (both of which are necessary for differentiation) except in individual minds. To posit an undifferentiated, unstructured thing in itself that gives rise to an unimaginably complex world of things on a vast range of scales is, to say the least, illogical.

At least Berkeley's idea that all that complexity is generated in the mind of God, which we all participate in, makes some logical sense.

The explanation on offer, "god did it", can account for anything, and so accounts for nothing. Not what I look for in an explanation.

I find it hard to make sense of "collective mind". — Banno

I'm with you on that, but can allow that others think it makes sense. I mean it's really the only thinkable alternative to a mind-independently existent world. -

Manuel

4.4k

Manuel

4.4k

There are many ranges to idealism, as you know. If you take idealism by the implication of the word, then the argument would be there is nothing in the world but ideas.

But there are restrained versions of it which argue is that what we access is necessarily mentally mediated - without making ontological commitments about what these objects are (non-mental, immaterial, mechanistic, etc.)

What you are critiquing here is the more extreme version. And then your criticisms here are quite apt. -

L'éléphant

1.8kFrom SEP - George Berkeley:

L'éléphant

1.8kFrom SEP - George Berkeley:

Berkeley defends idealism by attacking the materialist alternative. What exactly is the doctrine that he’s attacking? Readers should first note that “materialism” is here used to mean “the doctrine that material things exist”.

Thus, although there is no material world for Berkeley, there is a physical world, a world of ordinary objects. This world is mind-dependent, for it is composed of ideas, whose existence consists in being perceived. For ideas, and so for the physical world, esse est percipi. — RussellA

I think this needs further explanation. There's a difference between saying "there is no material world for Berkeley" and "matter cannot be, because we cannot perceive it" (matter to be defined here philosophically as physical and fundamental). When something is called fundamental, it is complete in its own right and could be perceived. Some matter are actually imperceptible and "exist" only in theory. Quarks are theoretical objects that are inferred or concluded from other perceptible objects. Berkeley's idea of 'fundamental' is an object that is complete -- the subject doing the perceiving, an apple, trees, and ocean, and the Earth.

Is matter, stripped of all the perceptible qualities and can only exist parasitically on other objects, a perceptible object? I understand by asking this, I am committing an error -- but please humor me. -

Janus

18kBut there are restrained versions of it which argue is that what we access is necessarily mentally mediated - without making ontological commitments about what these objects are (non-mental, immaterial, mechanistic, etc.) — Manuel

Janus

18kBut there are restrained versions of it which argue is that what we access is necessarily mentally mediated - without making ontological commitments about what these objects are (non-mental, immaterial, mechanistic, etc.) — Manuel

It's more that the way we access what we access is mentally mediated, and that is really a truism, even tautologous, If we say that perception is a mental process. -

Apustimelogist

946But, on a philosophical forum, and for philosophical purposes (introspecting the human mind), some form of Idealism — Gnomon

Apustimelogist

946But, on a philosophical forum, and for philosophical purposes (introspecting the human mind), some form of Idealism — Gnomon

Sure people are going to pick interpretations in ways aligned with their philosophical inclinations. I don't believe we should be picking them as a means to philosophical purposes. -

Manuel

4.4kIt's more that the way we access what we access is mentally mediated, and that is really a truism, even tautologous, If we say that perception is a mental process. — Janus

Manuel

4.4kIt's more that the way we access what we access is mentally mediated, and that is really a truism, even tautologous, If we say that perception is a mental process. — Janus

Sure - I entirely agree, it should be trivial. Some people might disagree, as with everything else in philosophy.

Now the only issue is if you are OK with saying some versions of idealism entail mental mediation or if you think idealism must entail something else. -

Apustimelogist

946BTW, even Bohm's*4 "realistic perspective" is typically labeled as a form of Idealism — Gnomon

Apustimelogist

946BTW, even Bohm's*4 "realistic perspective" is typically labeled as a form of Idealism — Gnomon

Bohmian mechanicsisjust straightforward realism that happens to involve non-locality. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kBut specifically for Berkeley, as an Immaterialist, he does not believe in a world of material substance, fundamental particles and forces, but he does believe in a world of physical form, bundles of ideas in the mind of God. — RussellA

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kBut specifically for Berkeley, as an Immaterialist, he does not believe in a world of material substance, fundamental particles and forces, but he does believe in a world of physical form, bundles of ideas in the mind of God. — RussellA

I take Berkeley to be arguing that we can do without the concept of matter. We can have a sufficient understanding of the external word, without the concept of "matter" to support substantial existence. In fact, I believe that the principal point he made is that "matter" does absolutely nothing for us, in aiding our understanding of reality. I think he believed it to be a completely useless concept. -

Wayfarer

26.2kIs matter, stripped of all the perceptible qualities and can only exist parasitically on other objects, a perceptible object? I understand by asking this, I am committing an error -- but please humor me. — L'éléphant

Wayfarer

26.2kIs matter, stripped of all the perceptible qualities and can only exist parasitically on other objects, a perceptible object? I understand by asking this, I am committing an error -- but please humor me. — L'éléphant

Right on point. Berkeley is objecting to the concept of matter as 'substance' in the philosophical sense - something which underlies the observable attributes, but which is separate to them. Recall that in the newly-emerging physics, and in John Locke, whom Berkeley was criticizing, the sharp distinction was made between primary attributes - quantitative, measurable and predictable mathematically - and how objects appear - color, scent, form, etc. So in that sense, 'matter' became an abstraction - something different from what appears to us. This is what I think Berkeley was protesting, but on purely empirical grounds. If all knowledge comes from experience - as Locke himself says - then how do we know this supposedly non-appearing, measurable 'stuff' we designate 'matter' actually exists?For Berkeley, that’s not empiricism, it’s speculation disguised as science.

Quite so! -

Apustimelogist

946I’m not alone in thinking that the many-worlds interpretation is wildly incoherent. — Wayfarer

Apustimelogist

946I’m not alone in thinking that the many-worlds interpretation is wildly incoherent. — Wayfarer

Your views are about as incoherent than Many Worlds. In fact, I think that Many Worlds is actually very coherent. Its fault is not intelligibility but that its just radically strange. Qbists and relationalist views are much more incoherent imo.

I believe that Bohm’s pilot waves have been definitely disproven — Wayfarer

It hasn't. Its extremely difficult to disprove interpretations that reproduce the same empirical predictions.

There's also my favored stochastic interpretation which doesn't have any of the pitfalls of the others and is completely locally realistic.

Nothing to do with ‘echo chambers’ more that you can’t fathom how any anti-realist interpretation could possibly be meaningful. — Wayfarer

Maybe. I just don't think you can say realism cannot possibly be true when these models are not falsified.

Why, do you think? — Wayfarer

Maybe try reading something from the last 75 years!

That is what he shares in common with positivism, but the conclusions he draws from it are radically different. — Wayfarer

Yes; like I said earlier, I just like to imagine he would come to different conclusions in a different context. He seems more cogent than most wooists; albeit, God. -

Wayfarer

26.2kIn fact, I think that Many Worlds is actually very coherent. Its fault is not intelligibility but that its just radically strange. Qbists and relationalist views are much more incoherent imo. — Apustimelogist

Wayfarer

26.2kIn fact, I think that Many Worlds is actually very coherent. Its fault is not intelligibility but that its just radically strange. Qbists and relationalist views are much more incoherent imo. — Apustimelogist

I can see why. I'll leave the explanations of its shortcomings to Phillip Ball. -

Apustimelogist

946If all knowledge comes from experience - as Locke himself says - then how do we know this supposedly non-appearing, measurable 'stuff' we designate 'matter' actually exists?For Berkeley, that’s not empiricism, it’s speculation disguised as science — Wayfarer

Apustimelogist

946If all knowledge comes from experience - as Locke himself says - then how do we know this supposedly non-appearing, measurable 'stuff' we designate 'matter' actually exists?For Berkeley, that’s not empiricism, it’s speculation disguised as science — Wayfarer

I like to say the same about your phenomenal-noumenal distinction. Not very useful, adding extra mystery where none needed. -

180 Proof

16.5k

180 Proof

16.5k

For him, perhaps it was; but nonetheless "matter" is very useful as a working assumption (like e.g. the uniformity of nature, mass, inertia, etc) for 'natural philosophers' then as it is now; certainly, as we know, not as "useless" of a "concept" for explaining the dynamics in and of the natural world as the good Bishop's "God" (pace Aquinas).I think [Berkeley] believed it to be a completely useless concept. — Metaphysician Undercover

:up: :up: -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kRecall that in the newly-emerging physics — Wayfarer

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kRecall that in the newly-emerging physics — Wayfarer

In the newly emerging physics, Newton had done something very interesting with his first law of motion, commonly known as the law of inertia. What Newton did, is replace the concept of "matter" with "inertia", as the defining feature of a body. We can understand a body as having inertia, instead of understanding it as having matter. So the emerging physics, which understood the principal property of a body as inertia, rather than as matter, rendered the concept of matter as redundant.

The concept of inertia was revolutionary, because it allowed "momentum" which is the opposing equivalent of inertia, to be transferred from one body to another as "force". Matter did not have this capacity, it was fixed within the body. The new physics did not require "matter" as a concept, "inertia" serves the purpose in a far more versatile way. And, that we could adequately understand the external reality without this concept, "matter", is what Berkeley argued.

For him, perhaps it was; but nonetheless "matter" is very useful as a working assumption (like e.g. the uniformity of nature, mass, inertia, etc) for 'natural philosophers' then as it is now; certainly, as we know, not as "useless" of a "concept" for explaining the dynamics in and of the natural world as the good Bishop's "God" (pace Aquinas). — 180 Proof

I argue above, that "inertia" effectively replaced "matter", making it a useless redundancy. The problem for many people, is that "inertia" is apprehended as far more abstract than "matter", and many cannot get their heads around the notion that a body is composed of inertia, something completely abstract. They like to think of "matter" as something non-abstract, which could provide the substance of a body. In reality, "matter" is absolutely abstract as well.

The trend at the time was to overthrow all Aristotelian principles of physics. Matter was an Aristotelian principle. Inertia was used to replace matter, and inertia's inverse principle, momentum allows that force is transferable from one body to another. Matter" could not provide this. So this theoretical principle, which replaced matter with inertia allows for the reality of energy-mass equivalence.

So, what is really the case, is that overthrowing the Aristotelian concept of "matter", leaving it in the dustbin, in preference of "inertia", is what enabled modern physics. That allowed for the mass-energy equivalence. Berkeley was quick to recognize that the concept "matter", had become obsolete, and was useless to science.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- What is the difference between subjective idealism (e.g. Berkeley) and absolute idealism (e.g. Hegel

- What does this philosophical woody allen movie clip mean? (german idealism)

- Idealism and "group solipsism" (why solipsim could still be the case even if there are other minds)

- Rationalism or Empiricism (or Transcendental Idealism)?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum