-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceYou can stipulate something like 'to exist is to stand out for a percipient' and of course on that definition nothing can exist absent percipients, which is basically what you are doing insisting: on your stipulated definition being the only "true" one. But that is a trivial tautology, and it is also not in accordance with the common usage of 'exist'. So, in Wittgenstein's terms, you are taking language on holiday. — Janus

As you mention Wittgenstein you might be interested in this snippet:

"Understanding a sentence," Wittgenstein says in Philosophical Investigations, "is more akin to understanding a theme in music than one may think." Understanding a sentence, too, requires participation in the form of life, the "language-game," to which it belongs. The reason computers have no understanding of the sentences they process is not that they lack sufficient neuronal complexity, but that they are not, and cannot be, participants in the culture to which the sentences belong. A sentence does not acquire meaning through the correlation, one to one, of its words with objects in the world; it acquires meaning through the use that is made of it in the communal life of human beings.

All this may sound trivially true. Wittgenstein himself described his work as a "synopsis of trivialities." — Wittgenstein's Forgotten Lesson

'participants in the culture to which the sentences belong. A sentence does not acquire meaning through the correlation, one to one, of its words with objects in the world; it acquires meaning through the use that is made of it in the communal life of human beings.' Quite in keeping with the theme of the original post, I would have thought.

RevealWittgenstein's statement “I am my world” occurs in the context of his discussion of the limits of the subject and its relationship to the world. Here, he is dealing with the nature of the self and its boundaries. The claim reflects the idea that the "self" is not an object in the world but rather the limit of the world—the perspective from which the world is experienced and represented.

This remark can be connected to Wittgenstein's earlier statement in the Tractatus (5.6): "The limits of my language mean the limits of my world." Language structures how we understand and engage with reality. The "world" in Wittgenstein's terms is the totality of facts, not things, and the "I" or "subject" cannot be a fact among these facts.

The self, as Wittgenstein understands it here, is a metaphysical subject, not a physical or psychological entity. This self is the necessary precondition for the world to appear but is not itself a part of the world.

This notion bears some resemblance to Schopenhauer's idea from The World as Will and Representation that "the world is my representation," where the world is fundamentally tied to the subject's experience of it. However, Wittgenstein departs from Schopenhauer in rejecting the metaphysical underpinning of "will" as an explanatory principle. -

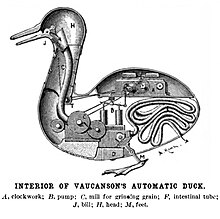

Behavior and beingSay you're building a model of a farmyard that includes a duck. Your model duck should look like a duck, waddle like a duck, quack like a duck, and so on. The important thing is that for each way a duck behaves that you're interested in, your model duck has a correlating behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

Like this, you mean?

Much as I've enjoyed building models over the years, I'm a little uncomfortable that the approach I'm describing has a sort of blindness. Whenever a question is raised about what something is, it is immediately rewritten as a question about how that thing behaves, so that we can get started modelling that bundle of behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

Like this, you mean? -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceCan you see the convergence between cognitive science and idealism?

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceI don't buy the kinds of arguments like Wayfarer makes; — Janus

Just as well I’m not selling, then. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceI agree Husserl, and German philosophy generally, is exceedingly verbose and often obtuse. That's why I admit to relying on secondary sources and synoptic accounts, although I own and have read fair amounts of the Crisis of the Western Sciences.

Phenomenology really came alive for me through the book The Embodied Mind, Varela, Thompson and Rosch. (Thompson is one of the authors of the Blind Spot.) Also Francisco Varela's interest in Buddhist abhidharma (philosophical psychology) really impacted me as I have an MA in Buddhist Studies and practiced vipassana for a long while. So the convergence between phenomenology and Buddhism is now a kind of genre in its own right. Another great exponent is the French philosopher of science, Michel Bitbol, whom I learned about here on this forum. I love his style. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceI would only add that the article itself does not claim to represent transcendental idealism but phenomenology. I am responsible for any equivocation between the two.

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceDo you agree with the argument that science has a blind spot? You gave the kind of objections that a Burge might give, but then you say you don’t agree with Burge on that score. So do I take it that you are in agreement with the authors?

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceAllow me to quote Meillassoux at this point — Arcane Sandwich

I'm keeping away from him, and from 'speculative realism' generally. There's a considerable body of work there but still within the generally physicalist-naturalist ambit, and I'm defending an idealist philosophy. Bernardo Kastrup is more my cup of tea. And philosophical cognitive scientist John Vervaeke, who's not an idealist philosopher, but is doing fantastic work on history of ideas.

Those things are still there when I go to sleep, and they are the same things that I find in the morning when I wake up. — Arcane Sandwich

You are in good company.

in practice it is surprisingly difficult to get transcendental idealism taken seriously, even by many good philosophers. Once, in Karl Popper's living-room, I asked him why he rejected it, whereupon he banged his hand against the radiator by which we were standing and said: 'When I come downstairs in the morning I take it for granted that this radiator has been here all night'‚ a reaction not above the level of Dr Johnson's to Berkeleianism — Bryan Magee, Schopenhauer's Philosophy

The reaction of Johnson to Berkeley is the (in)famous Argument from the Stone.

Magee goes on:

Some of the best of empiricist philosophers have regarded transcendental idealism as so feeble that they have spoken patronizingly of Kant for putting it forward‚ from James Mill's notorious remark about his seeing very well what 'the poor man would be at', to passages in P. F. Strawson's The Bounds of Sense in which the author calls transcendental idealism names without bothering to argue seriously against it, and toys playfully with the question whether Kant was perhaps having us all on in putting it forward. ...Strawson appears from the outset to take it as having been already agreed between himself and his readers that transcendental idealism is some sort of risible fantasy, and therefore that Kant's constructive metaphysics will merit our attention only on condition that it can be shown to be logically independent of [it].

That would describe the attitude of most of the contributors here, with some illustrious exceptions (including the one directly above this post). -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceI'd recommend Quentin Meillassoux's book — Arcane Sandwich

He’s been discussed here, I’ve taken a look. Mine is the kind of argument he has in his sights.

There are things that exist outside of my brain. — Arcane Sandwich

That statement is made from a point of view outside both, which takes the brain as one object among others.

Those things are still there when I go to sleep, and they are the same things that I find in the morning when I wake up. — Arcane Sandwich

Yet amazing as it may seem, that is not an argument against transcendental idealism. There’s an anecdote that Bryan Magee tells about Karl Popper on this point, I’ll find it later. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceI will clarify that while I acknowledge the reality of empirical and so mind independent facts, reality as a whole is not mind independent, even though we can putatively imagine it as if it were.

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceThe argument is about whether things exist without minds. I say not, Banno references a gold discovery at a particular place as an example of a putatively mind-independent fact. This argument is interminable.

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceBetter start digging, then!

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceSure. Whatever floats your (ideal) boat.

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceSure. Beats scientism hands down.

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceIt’s the zeitgeist, the spirit of the age. That’s how I see it. Many great thinkers expressed similar sentiments in the 20th Century. But the times, they are a’changin’.

There are three aspects to this account that I think are salient. — Banno

Actually I think you’ve conflated this thread with the other one, Mind Created World, although they’re obviously related. My point in that other thread is simply that it is meaningless to say that of anything that it exists outside of or independently of any perspective, which I don’t think your patiently-explained butterfly effect (forgive the conceit) actually addresses. Outside any perspective, there is….well, you can’t say. That’s the point, and it’s a simple one.

This is in contrast to Wayfarer's thesis that science neglects lived experience. A better way to think of this is that science combines multiple lived experiences in order to achieve agreement and verity. — Banno

Firstly, the ‘Blind Spot of Science’ was not written by me but by Adam Frank (cosmologist), Evan Thompson (philosopher) and Marcello Gleiser (physicist) on the basis of Whitehead’s process philosophy and Husserl and Merleau Ponty’s phenomenology. And they would have no problem agreeing with the principle of inter-subjective validation. What they’re objecting to is the over-valuation of objectivity as the sole criterion of what is actual, the idea that science provides a transparent window on the world as it truly is. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived Experience

It does, actually. And forgive any intemperance on my part, but it is a subject that pushes buttons (although to be fair, it works both ways.) But at any rate, it’s kind of re-assuring to read those remarks.does that answer your question, or not? — Arcane Sandwich

Do you think this attitude of Bunge’s could fairly by described as ‘scientism’? -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceI think it conveys a superficial grasp of what he’s intending to criticise. But it’s really the tone rather than the substance of the comments. ‘It proves to be nothing but transcendental idealism’ as if that itself provides sufficient condemnation. Whereas, it is my view that transcendental idealism stands the test of time, and that it is not for nothing that the Critique of Pure Reason is regarded as one of the seminal philosophical books of the modern period. Basically, Bunge is simply appealing to the like-minded.

Go back to the passage I quoted:For Husserl it is not that consciousness creates the world in any ontological sense… but rather that the world is opened up, made meaningful, or disclosed through consciousness. The world is inconceivable apart from consciousness. Treating consciousness as part of the world, reifying consciousness, is precisely to ignore consciousness's foundational, disclosive role. For this reason, all natural science is naive about its point of departure, for Husserl. Since consciousness is presupposed in all science and knowledge, then the proper approach to the study of consciousness itself must be a transcendental one. — Source

I find that neither obscure or opaque. What do you think is wrong with it? -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceWell, mere indignation does not an argument make. Bunge only conveys that he finds phenomenological literature ‘opaque’ - which it often is - but offers no argument against it in that passage, other than the implication that it’s obviously wrong. So, what’s wrong with it?

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived Experience. How can I contribute to this discussion, now? — Arcane Sandwich

Well, I noticed reading Mario Bunge's Wikipedia entry that he's critical of phenomenology. I have never read anything about him, but it might be a good starting point, as that article is grounded in phenomenology.

For example, here's a quotation from the Routledge Introduction to Phenomenology about Husserl's criticism of naturalism:

In contrast to the outlook of naturalism, Husserl believed all knowledge, all science, all rationality depended on conscious acts, acts which cannot be properly understood from within the natural outlook at all. Consciousness should not be viewed naturalistically as part of the world, since consciousness is precisely the reason why there was a world there for us in the first place. For Husserl it is not that consciousness creates the world in any ontological sense… but rather that the world is opened up, made meaningful, or disclosed through consciousness. The world is inconceivable apart from consciousness. Treating consciousness as part of the world, reifying consciousness, is precisely to ignore consciousness's foundational, disclosive role. For this reason, all natural science is naive about its point of departure, for Husserl. Since consciousness is presupposed in all science and knowledge, then the proper approach to the study of consciousness itself must be a transcendental one - one which… focuses on the conditions for the possibility of knowledge. — Source

How do you think a Mario Bunge would respond to that criticism? -

The Mind-Created WorldI believe that's what Nagel means. I think "There's something it's likes to be a bat" means "There's something it feels like to be a bat." But not a physical feeling. At least not only physical feelings. Do you have a feeling of your own existence aside from your physical body? — Patterner

I think the obvious but un-stated point in David Chalmer's famous paper, Facing up to the Problem of Consciousness, is about the nature of being. Consider the central paragraph:

The really hard problem of consciousness is the problem of experience. When we think and perceive, there is a whir of information-processing, but there is also a subjective aspect. As Nagel (1974) has put it, there is something it is like to be a conscious organism. This subjective aspect is experience. When we see, for example, we experience visual sensations: the felt quality of redness, the experience of dark and light, the quality of depth in a visual field. Other experiences go along with perception in different modalities: the sound of a clarinet, the smell of mothballs. Then there are bodily sensations, from pains to orgasms; mental images that are conjured up internally; the felt quality of emotion, and the experience of a stream of conscious thought. What unites all of these states is that there is something it is like to be in them. All of them are states of experience.

'Something it is like to be...' is actually an awkward way of referring to 'being' as such. We are, and bats are, 'sentient beings' (although in addition h.sapiens are rational sentient beings), and what makes us (and them) sentient is that we are subjects of experience. When the term 'beings' is used for bats and humans, this is what it means. And the reason that 'the nature of being' is such an intractable scientific problem is that it's not something we are ever outside of or apart from, and thus it can't be satisfactorily captured or described in objective terms. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceI note Mario Bunge is a compatriot of yours! I’d never heard of him prior to your mention of him, but insofar as he describes himself as materialist, then I’m duty bound to disagree with him, and reading his Wikipedia entry, I see he devoted his life to arguing against what this essay is arguing for. So I suppose it might make for an interesting clash of views, but perhaps read a bit more into that essay and bring up a few more points.

-

Is factiality real? (On the Nature of Factual Properties)But (and I ask this genuinely, no offense meant) is there any scientific evidence that karma exists? I don't think there is. Which means that if you wish to convince me that karma exists, you will have to do so by way of reason, not of poetry. Logos instead of Mythos, if you will. — Arcane Sandwich

I don't know if there is 'scientific evidence' for karma, but the principle is, in essence, that all actions have consequences. The Biblical maxim 'as you sow, so shall you reap' adds up to the same, although the word itself is of Indian origin (from the root word 'kr-' 'to do'.) Obviously a stumbling block for Western culture is the implicit entailment of karma accumulating across lifetimes, which is not something I would try and persuade anyone to believe. But even as metaphor, the fact that all actions shape your life surely is a sound basis for an ethical philosophy.

Other than that, I think @Mapping the Medium‘s response is pretty good. One of the topics I’ve learned a ton about on this forum is ‘biosemiotics’ (ref), from a one-time contributor here with expert knowledge in the subject. It’s as good a perspective as any through which to pursue such questions.

//

it quickly discovers that, in this way, its labours must remain ever incomplete, because new questions never cease to present themselves; and thus it finds itself compelled to have recourse to principles which transcend the region of experience, while they are regarded by common sense without distrust. It thus falls into confusion and contradictions…. — Mww

…and then it joins a Forum. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceSure. It's a discussion of an essay published in Aeon in 2019, The Blind Spot, Adam Frank, Marcello Gleiser and Evan Thompson, so reading that would be a good starting point.

-

Is factiality real? (On the Nature of Factual Properties)Why is my existence as a person (and as an "Aristotelian substance") characterized by the factual properties that I have, instead of other factual properties? — Arcane Sandwich

Memory, isn’t it? And the consequences of all of the preceding acts that gave rise to your particular existence?

Not only did I not choose to be born, I didn’t even choose to be born in this place instead of that place. — Arcane Sandwich

Hindus and Buddhists believe otherwise. And all of the specifics you mention a consequence of karma.

By the way, enjoying your contributions thus far. -

The Mind-Created WorldIf we think of it akin to personality disorder, which Kastrup does quite often, then we would expect trauma to cause a disassociation (i.e., an alter) or at least something significantly violent or powerful; but, because we know sex produces life, Kastrup must hold with consistency that sex somehow is the act that forces the Mind to disassociate from itself. Sex, simpliciter, is not violent; it is not traumatic; it is not particular powerful; etc. — Bob Ross

Of course it is true that the psychiatric disorder is often the product of trauma or mental illness, but I think that is not essential to Kastrup's point. He introduces it as an analogy to explain how a 'universal consciousness' can come to appear as instances of individual consciousness. Kastrup posits that cosmic dissociation occurs at the level of living organisms rather than that of elementary particles. He references metabolic processes and empirical findings to support this view, emphasizing that organisms’ boundaries are physically and phenomenally distinct from those of inorganic matter. Reproduction, whether sexual or asexual, involves the establishment of new boundaries that separate one organism (or alter) from another. In Kastrup's framework, this 'boundary formation' is the physical manifestation of dissociation within the universal consciousness. The boundaries of living organisms are unique and distinct compared to inanimate matter, as they encapsulate metabolic and phenomenological processes. So, as said above, while I quite understand why you might think the entire idea is implausible, I don't really see why sexual reproduction in particular poses a challenge to it. -

Mathematical platonismBut then I have another follow-up question. There are four apples on the table. I claim (I might be wrong, of course) that those four apples are still four apples even when no one is looking at them (i.e., "intending" them in any way, as in Husserl's concept of intentionality as a subject-object relation). I would say, the number "one" exists, like an "Aristotelian accident", in each of the four apples. And that "one-ness", if you want to call it that, doesn't somehow "dissipate", or "cease to be", when no one is contemplating the apples, or thinking about them in any sort of way. It's just a brute fact that there are four apples on the table instead of five or three. — Arcane Sandwich

What you're referring to is 'brute fact' is actually just direct realism, the view that the world is perceived exactly as it is. But that fails to account for the role of the mind in shaping our perception of order and numerical concepts. It fails to grasp the fact that the order we perceive in the world, numerical and other, arises as a consequence of the interaction of mind and world. I acknowledge that in practical, everyday terms, it may seem straightforward to assert the existence of four apples, but this perception is itself mediated by observation and verification, verifying that they're real apples and not fakes or holographs, etc, of which requires observation. This is the subject of another OP The Mind-Created World, also discussed here, a defense of a form of phenomenological idealism. -

Mathematical platonismMy follow-up question would be, are they physical? Like, are they somewhere, in spacetime? Are they in our head, in some sense? Not necessarily in the brain, but then where? In "the mind", assuming that "the mind" is something other than the brain? Are they outside the brain? Where are they? In the things, themselves? — Arcane Sandwich

I think that is due to the cultural impact of empiricism. Because of this we are enculturated to believe that what is real can only be in located in space-time. Notice in that Smithsonian essay:

...scholars—especially those working in other branches of science—view Platonism with skepticism. Scientists tend to be empiricists; they imagine the universe to be made up of things we can touch and taste and so on; things we can learn about through observation and experiment. The idea of something existing “outside of space and time” makes empiricists nervous: It sounds embarrassingly like the way religious believers talk about God, and God was banished from respectable scientific discourse a long time ago.

But there's another approach - that of phenomenology. @Joshs is adept at explaining that (see this post.) My take is that numbers and logical principles are necessary structures of consciousness. That doesn't mean they're the product of the mind i.e. they're not neurobiological structures but intentional structures in Husserl's sense. -

Mathematical platonismSomething (i.e. a number) can be real without being material? How can that be? I'm admittedly a scientific materialist. — Arcane Sandwich

Well, I think we have - no offense or anything - a flawed understanding of what is real. (After all, it's the business of philosophy to make such judgements.)

He says that the number 3, for example, is just a brain process. — Arcane Sandwich

This is 'brain-mind identity theory' which was prominent in the work of a couple of Australian philosophers, J J C Smart and D M Armstrong.

The fly in the ointment here is what exactly is meant by 'the same'. When you say that a brain process is 'the same as' a number then you're already well into the symbolic domain. There's no feasible way to demonstrate that a particular brain process - in fact, there are no particular brain processes, as brains are fiendishly irregular and unpredictable - 'means' or 'is' or 'equates to' anything like a number (or any other discrete idea.) And indeed an argument of this type has an ancient provenance. It appears in Plato's dialogue The Phaedo, in which Socrates makes a vital point about the implication of our ability to perceive the nature of 'equals'. When we see two things that are of equal dimensions, say, two stones or two pieces of wood, we are able to discern that they are equal - but only because we innately possess the idea of 'equals':

Socrates: "We say, I presume, that there is something equal, not of wood to wood, or stone to stone, or anything else of that sort, but the equal itself, something different besides all these. May we say that there is such a thing or not?"

Simmias: "Indeed, let us say most certainly that there is. It is amazing, by Zeus."

"And do we know what it is?"

"Certainly," he replied.

"From where did we obtain the knowledge of this? Isn't it as we just said? From seeing pieces of wood or stone or other equals, we have brought that equal to mind from these, and that (i.e. 'the idea of equals') is different from these (i.e. specific things that are equal)".

The Phaedo 74a ff

Another argument is a version of Putnam's multiple realisability - that a number (or any item of information) can be realised in any number of ways by different brains (or in different media or symbolic types, for that matter.) Neuroplasticity demonstrates the brains of injured subjects can be re-configured to grasp language or number with neural areas not usually associated with those functions. That's also a version of multiple realisability.

And in even thinking about these problems, you're all the time making judgements and reasoned inferences ('if this, then that', 'this must be the same as that' etc.) You can't even define what is physical without relying on those rational faculties, yet brain-mind identity claims that they are somehow the same.

So my view would be that, wherever rational sentient beings exist, there must be a core of real ideas that they are able to grasp, and these are discovered, not invented. -

Mathematical platonismDoes it make sense to agree with Platonism on some intellectual fronts but not in others? — Arcane Sandwich

I'm sure it does. After all, just what Platonism is, over and above the actual dialogues, is always being refined and re-envisioned. My sole philosophical commitment is to what I consider an elementary philosophical fact: that number is real but not material in nature. Of course there are nowadays kinds of neo-pythagorean views, like Tegmark's, but that's not what I have in mind, as Tegmark is, perplexingly enough, still a pretty standard-issue scientific materialist in other ways.

But the point I've been pressing, pretty well ever since joining forums, is that some ideas are real in their own right, not reducible to neural activity or social convention or the musings of experts. We discussed Frege upthread, about whom I know not much, but he is nevertheless instinctively Platonist, in believing that numbers and basic arithmetical operations are metaphysically primitive, i.e. can't be reduced or explained in other terms. In other words, it's a defeater for materialism, and that is why it is so often rejected in the modern academy.

But there are many controversies. Take a look at What is Math? a Smithsonian Magazine article I cited earlier in this thread. I think it lays bare many of the contentious issues. (After reading that article, I purchased a copy of the book by the emeritus professor mentioned in it, James Robert Brown, Platonism, Naturalism, and Mathematical Knowledge, but alas, much of it was beyond my ken. Review here.) -

Mathematical platonismSpeaking from a purely personal POV, I think that Natural numbers might objectively exist, and perhaps Real numbers as well. But when you get to stuff like the set of Complex numbers, things just don't make sense anymore. — Arcane Sandwich

Agree. But don't you think that the qualifier 'objective' might be inappropriate in the context? But then, what are the alternatives? The point being, 'objective' means 'inherent in the object/s'. But numbers are not objects per se, they're intellectual acts. We use mathematical techniques to determine what is objective. Not that they're subjective, either, but that their truth status is in some sense transcendental (but then, you can't use that, because 'transcendental numbers' are a special case in mathematics.)

Which is what leads me to speculate that the natural numbers are real but not existent. They are, in a sense other than the Kantian, 'noumenal' - objects of intellect (where 'object' is used metaphorically). But they are also indispensable to rational thought. That is part of the version of mathematical Platonism that makes sense to me. -

Mathematical platonismBut if something can't be said, it might be important to say why and surely philosophy has a role to play there.

— Wayfarer

I . . . take [it] to be one of the main themes of the Investigations - that what cannot be said may be shown or done.

— Banno

I just want to point out that these two views are not the same. You can indeed move on from inexpressibility to a demonstration or showing of what can't be expressed. But first (or conjointly) you can also say why, as Wayfarer suggests. Or would the claim be that inexpressibility itself can only be demonstrated, not justified? — J

Thanks for picking up on that. I was saying, Wittgenstein's famous 'that of which we cannot speak....' is often used as a fireblanket to suppress discussion of the mystical, which I feel is one facet of philosophy. I peruse the Tractatus (which I've never studied formally or read in full), there are aphorisms which ring true, and many others I don't understand at all. The one that I always recall is 6.41:

The sense of the world must lie outside the world. In the world everything is as it is and happens as it does happen. In it there is no value—and if there were, it would be of no value.

If there is a value which is of value, it must lie outside all happening and being-so. For all happening and being-so is accidental.

What makes it non-accidental cannot lie in the world, for otherwise this would again be accidental.

It must lie outside the world.

I'd like to ask, 'Why is that?'

Is the answer 'Shuddup already' :rage: ?

he here cannot be wrong. — Banno

But he can be jejune.

"For it does not admit of exposition like other branches of knowledge; but after much converse about the matter itself and a life lived together, suddenly a light, as it were, is kindled in one soul by a flame that leaps to it from another, and thereafter sustains itself" ~ Plato, VII Letter — Count Timothy von Icarus

That resonates with the legendary origin of Ch'an Buddhism, namely, the Flower Sermon, wherein the Buddha's insight is transmitted worldlessly to one Mahakasyapa, the only monk to smile when the Buddha gazes at a flower, and the origin of what is thereafter designated a 'special transmission outside the scriptures' - notwithstanding that this tradition also generated a vast corpus of written texts about what supposedly could not be transmitted by them. Something similar is also discernable in the 'doctrine of divine illumination', associated with Augustine, and about which there's an article on SEP.

Having said that, I also understand that the mystical is something which engenders vastly different responses in people. It resonates for some, and not at all for others, and it is also a fertile source of both exploitation and delusion. I've always felt an affinity for it and I do think that properly grasped, there are self-validating elements in such teachings, but only if they are properly grasped. That is what it 'has to be done' refers to: they're dynamic principles that have to realised in both sense of made real, and understood properly. -

The Mind-Created WorldAccording to his logic, people conceiving a baby is somehow an instance of the Universal Mind disassociating from itself thereby creating an alter. — Bob Ross

Given that cosmic consciousness is likely to be viewed as wildly implausible by many people, what in particular about this aspect of it is particularly implausible? It jibes with the ancient tropes of the descent of the soul. -

In defence of the Principle of Sufficient ReasonThe question again: can you stipulate some thing which is neither temporally delimited nor composed of parts? I suggest not.

either there is a foundation, or there's a vicious infinite regress of ever-deeper layers of reality - which I reject. — Relativist

So you acknowledge that science can’t say what the foundation is, but you nevertheless claim, presumably as an act of faith, that if there is a foundation, then it must be material in nature.

At some stage in history materialism might have been able to claim that the atom was imperishable and eternal - which was, after all, the basis of materialism in Greek philosophy - but that is no longer considered feasible. Fundamental particles, so-called, have an intrinsically ambiguous nature, and they seem to be at bottom to be best conceived as an excitation of fields, however fields might be conceived.

I personally reject deism because it depends on an infinitely complex intelligence, with magical knowledge, just happening to exist by brute fact. — Relativist

That’s a Richard Dawkins argument - that whatever constructs must be more complex than what is constructed by it. But in the classical tradition, God is not complex at all, but is simple. And the best analogy I can think of for that is - you! Your body comprises billions upon billions of cells, the brain is the most complex natural phenomenon known to science with more neural connections than stars in the sky (or so I once read). And yet, you yourself are a simple unity. That, I think is the meaning (or one meaning) of ‘imago dei’. -

The Lament of a Spiritual AtheistHowever, if the adage “magic is science we don’t understand yet” is true, then the reverse may also be true: that science is magic that we do understand. — MrLiminal

I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics. — Richard Feynman, Nobel Laureate in Physics

And yet, these devices we’re using to read and write these ideas depend on it!

:up: -

Mathematical platonism”Intellectus is the higher, so that if we call it ' understanding', the Coleridgean distinction which puts 'reason' above ' understanding' inverts the traditional order. Boethius, it will be remembered, distinguishes intelligentia from ratio; the former being enjoyed in its perfection by angels” — Count Timothy von Icarus

Intellectus is the Latin term adopted by Roman philosophers like Cicero and later by medieval Scholastics to translate nous from Greek philosophical texts. It similarly denotes the capacity for intellectual intuition or understanding of universal principles. Nous (and therefore Intellectus) is a key term for the higher faculty of the soul, distinct from reason (ratio), which operates discursively. … In the Aristotelian scheme, nous is the faculty that underwrites the capacity of reason. For Aristotle, nous was distinct from the processing of sensory perception, including the use of imagination and memory, which animals can do. For Aristotle, discussion of nous is connected to discussion of how the human mind sets definitions in a consistent and communicable way (through the grasp of universals) and whether people must be born with some innate potential to understand the same universal categories in the same logical ways. Derived from this it was also sometimes argued, in classical and medieval philosophy, that the individual nous must require help of a spiritual and divine type. By this type of account, it also came to be argued that the human understanding (nous) somehow stems from this cosmic nous, which is however not just a recipient of order, but a creator of it. — various sources including Wikipedia -

In defence of the Principle of Sufficient ReasonSubjects of experience are not things, which is why treating subjects as things is generally considered inappropriate. And why personal pronouns are used for subjects and not for objects (‘it’, ‘that’).

Your hypothetical material ontological foundation is also something that science had not been able to show exists albeit on different grounds. What would be an example of a thing which has no beginning and end in time and is not composed of parts?

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum