-

The Mind-Created WorldDespite what some Westerners like to believe, Buddhism is not a philosophy and is not intended to be discussed at philosophy forums, in the manner of Western secular academia. — baker

Says you, who just this minute has pasted an entire paragraph from the Pali texts into another thread.

I don’t see any ‘bad blood’. Hostile reactions are only to be expected when people’s instinctive sense of reality is called into question. I know mine is a minority position but that in itself gives me no concern. -

The Nihilsum ConceptOne area would be the idea of prime matter as sheer, indeterminate potency with no actuality, no eidos (form), and thus absolutely lacking in any intelligible whatness (quiddity) — Count Timothy von Icarus

Perhaps that’s a precursor for what was to become the ding an sich of Kant (I don’t know if that’s a recognised theory.) The many arguments I’m having about idealism revolve around the idea that in the absence of the order which an observing mind brings to bear, nothing exists as such. Not that it doesn’t exist, but there is no ‘it’ which either exists or doesn’t exist. The delineation of forms and the differentiation of things and features one from another is what ‘existence’ means, it is the order that ‘brings things into existence’, so to speak. (For which the ‘observer problem’ is an exact analogy.) -

The Mind-Created WorldBut unless one is enlightened, one cannot talk about these things with any kind of integrity — baker

My reference to Buddhism was in respect of a glossary term in Buddhist lexicon which was relevant to the question. I’m not ‘offering teachings’ or putting myself up as enlightened. This is a philosophy forum, and this thread a discussion of a philosophical topic, if it makes you uncomfortable then perhaps you shouldn’t involve yourself. -

The Nihilsum ConceptThe "Nihilsum" represents a state that defies conventional logic by existing in a realm between what we establish as being and non-being. It cannot be fully categorized as something or nothing; it is also the absence of either. — mlles

Aristotle beat you to it.

Quantum math is notorious for incorporating multiple possibilities for the outcomes of measurements. So you shouldn’t expect physicists to stick to only one explanation for what that math means. ... One of the latest interpretatations appeared recently (September 13 2017) online at arXiv.org...

In the new paper, three scientists argue that including “potential” things on the list of “real” things can avoid the counterintuitive conundrums that quantum physics poses. It is perhaps less of a full-blown interpretation than a new philosophical framework for contemplating those quantum mysteries. At its root, the new idea holds that the common conception of “reality” is too limited. By expanding the definition of reality, the quantum’s mysteries disappear. In particular, “real” should not be restricted to “actual” objects or events in spacetime. Reality ought also be assigned to certain possibilities, or “potential” realities, that have not yet become “actual.” These potential realities do not exist in spacetime, but nevertheless are “ontological” — that is, real components of existence.

“This new ontological picture requires that we expand our concept of ‘what is real’ to include an extra-spatiotemporal domain of quantum possibility,” write Ruth Kastner, Stuart Kauffman and Michael Epperson.

Considering potential things to be real is not exactly a new idea, as it was a central aspect of the philosophy of Aristotle, 24 centuries ago. An acorn has the potential to become a tree; a tree has the potential to become a wooden table. Even applying this idea to quantum physics isn’t new. Werner Heisenberg, the quantum pioneer famous for his uncertainty principle, considered his quantum math to describe potential outcomes of measurements of which one would become the actual result. The quantum concept of a “probability wave,” describing the likelihood of different possible outcomes of a measurement, was a quantitative version of Aristotle’s potential, Heisenberg wrote in his well-known 1958 book Physics and Philosophy. “It introduced something standing in the middle between the idea of an event and the actual event, a strange kind of physical reality just in the middle between possibility and reality.” — Quantum Mysteries Dissolve if Possibilities are Realities

If you think about it, the same general logic applies to the 'domain of possibility'. At any given time, in any situation, there is a finite but incalculable number of possible outcomes. All of those are real in one sense, but not existent, by definition, and ultimately only one of them becomes actual. Which is pretty well the same thing that happens in observations in quantum physics. -

The Mind-Created WorldBut do you believe I can find in your critical comments something more insightful than the willful non-engagement I've found in Strawson, Nagel, Searle, etc.? — goremand

They're all different. We've had debates here about Strawson's panpsychism, which I've never agreed with. I think he tries to rescue materialism by injecting matter with some kind of 'secret sauce'. The same goes for Philip Goff. (Actually, Goff once signed up for this forum, purely to respond to my criticism of one of his articles, which I was chuffed by.) Searle, I've only ever read the Chinese Room argument, but I think it stacks up. As for Thomas Nagel, he's been a pretty vociferous critic of Dennett. But the best overall take-down is The Illusionist, David Bentley Hart, in The New Atlantis, in which he says some of Dennett's arguments are 'so preposterous as to verge on the deranged' (although a close runner-up would be The God Genome by Leon Wieseltier, a review of one of his books). -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrong"Our immensely sophisticated hominid forebrain generates the world in which there is space, time, and perspective", then there is an immensely sophisticated hominid forebrain, logically prior to there being a generated world. I can't imagine how you could reconcile these two things. The brain is a part of the world it supposedly produces. — Banno

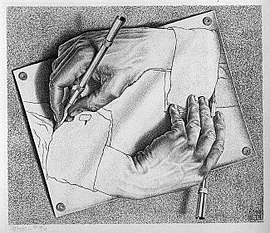

That is indeed the 'strange loop': logical priority is a product of the brain, which in turn is a product of evolution.

Because you understand temporal sequence, you can imagine a world that would exist as if there were no observer in it - but that still is dependent on the mind. That's what I mean (and Husserl means) by 'implicit perspective'. 'Before man' or 'before I was born' are still mind-dependent. We can talk about them because we both possess the conceptual and linguistic resources within which it's meaningful to do so. But to us, the world is idea - not in the sense of representative realism, where the idea 'represents' but is separate from 'the object'. The whole process of the understanding comprises assimilating percepts and concepts into coherent wholes which are ideas (gestalts in Pinter's book). We believe that all of that would continue to exist outside that process, but being outside that process is, to all intents, being unconscious (or dead) - so we don't really know. As long as we're alive, that is what the mind is doing. We're not seeing it from no perspective, as it really would be with no observer in it, because then it wouldn't have any form, scale or perspective. It would not be a world. Which is not the same as saying that it would pass out of existence or that everything would dissappear.

See Schopenhauer’s Idealism: How Time Began with the First Eye Opening.

They first set up the objective/subjective dichotomy and then ignore half of it. — Banno

That is not inconsequential, I think it's a factor of considerable importance. That is the hallmark of the modern era beginning with Descartes. The very word 'objectivity' only came into use in the early modern period. And scientific naturalism has tended - I use past tense, because it is changing - to try to analyse everything from 'the view from nowhere' as Nagel says in his book. -

What's happening in South Korea?This is no longer a country where belief in democracy prevails. — frank

alternatively, the voters don't really understand what is at stake. There is after all unprecedented amounts of misinformation and commercially-sponsored state propaganda, to all intents and purposes. Turns out you can fool most of the people, most of the time. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongThe part on which it seems we disagree is that since not just any understanding will do, there is something else that places restrictions on the understanding we construct. — Banno

It is determined by both external and internal factors. There are definitely 'facts of the matter' as I've acknowledged.

I'm considering the idea that while there are inummerable objective facts, the existence of the world is not one of them. Our immensely sophisticated hominid forebrain generates the world in which there is space, time, and perspective, and within which individual particulars have features, location, composition, and the other attributes.

The complaint I have is against those philosophies that seek explanation only in objective terms, as they don't take the role of the mind (or brain) into account in what they consider to be real. The self-other division is implicit in all objective philosophies, but it is not acknowledged. It is, as Schopenhauer says, the philosophy of the subject who forgets himself.

This is the background to that exclamatory statement in the Critique of Pure Reason, 'take away the thinking subject, and the whole world must vanish'. Your instinctive response to that is 'tosh' - and I really do understand that. It sounds utterly outlandish or fantastic in isolation. But taken against the background of the rest of the critique, it is compatible with the overall insight of the constructive role of the mind in the world.*

Without that initial construction, 'gold, 'boorara' and 'exists' would all be meaningless noises. There would be no locations, no objects, nothing to speak of whatever.

I've been reading up on Hilary Putnam, who is referred to in the SEP article. HIs focus is narrower but not entirely incompatible: that the same phenomena can be explained in different and even incommensurable terms. He gives examples from mathematics, logic and science.

For Putnam, metaphysical realism boils down to the idea that the facts of the world (or the truth of propositions) are fixed by something mind-independent and language-independent. As a consequence of this idea, Putnam suggests that the Metaphysical Realist is committed to the existence of a unique correspondence between statements in a language or theory and a determinate collection of mind and language-independent objects in the world. Such talk of correspondence between facts and objects, Putnam argues, presupposes that we find ourselves in possession of a fixed metaphysically-privileged notion of ‘object’. Since it is precisely this possibility of dictating a right notion of concepts such as ‘individual’ and ‘object’ that Putnam takes the phenomenon of conceptual relativity to undermine, he naturally concludes that conceptual relativity presents a deep and insurmountable challenge to Metaphysical Realism. — Hilary Putnam and Conceptual Relativity, Travis McKenna

----

*I have briefly perused Bounds of Sense in the past, but I understand Strawson's critics (e.g. Henry Allison) to be saying that his analysis flattens out or naturalises Kant and in effect discards the baby with the bathwater. -

What's happening in South Korea?this conversation is drifting towards The Trump Thread, although that thread is of course ghosted by our own dedicated MAGA fanatic.

-

What's happening in South Korea?I'm still hopeful that American democracy will hold, although of course it's still day -44. But when DJT begins to try and enact his revenge and deportation agendas, and dismantle environmental protections - that's when we'll see.

-

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongAs asked previously, where do you differ with the SEP description? ‘According to metaphysical realism, the world is as it is independent of how humans...take it to be. The objects the world contains, together with their properties and the relations they enter into, fix the world’s nature and these objects [together with the properties they have and the relations they enter into] exist independently of our ability to discover they do. Unless this is so, metaphysical realists argue, none of our beliefs about our world could be objectively true since true beliefs tell us how things are and beliefs are objective when true or false, independently of what anyone might think.’ Doesn’t the ‘there is gold at Boroora’ argument fall under this heading?

-

The Mind-Created WorldI'd love to read an attack on physicalism, especially of the eliminativist variety — goremand

I have a long history of posting critical comments about Daniel Dennett, who is the main representative of eliminative materialism.

Bernardo Kastrup is strident in his criticism of materialism, with titles such as Materialism is Baloney. But he’s not well-regarded on this forum either, the consensus being in threads posted in years past that he’s dismissed as an eccentric or a crank. I don’t in the least agree with that description, but I also mention him only sparingly from time to time. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongwho introduced "If everything remains undisturbed then there will be Gold", quoting someone else. — Banno

You’re referring to the abstract of the introduction of Pinter’s book Mind and the Cosmic Order, which I quoted, which says in the early Universe, ‘There is no human or animal eye to cast a glance at objects, hence nothing is discerned, recognized or even noticed. Objects in the unobserved universe have no shape, color or individual appearance, because shape and appearance are created by minds.’ When intelligent life evolves, then it will discover that gold is amongst the constituents of the Earth. I don’t read that as supporting metaphysical realism. -

In defence of the Principle of Sufficient ReasonMind or nous as the governing principle, arranging things according to what is best, is not the same as a world governed by reason.

For Aristotle, the question of the intelligibility of the natural world faces two problems, the arche or source of the whole and tyche or chance. We have no knowledge of the source and what happens by chance or accident does not happen according to reason. — Fooloso4

Thanks, interesting distinctions. Tyche shows up as Pierce’s ‘tychism’ which I too believe is intrinsic to the order of things. -

What's happening in South Korea?So the positive side here might be the democratic system in South Korea prevailed. At least for now. — ssu

It seems to have. -

The Mind-Created WorldIn other words, it is a claim that is compatible with some forms of realism. — goremand

Sure. That’s a very broad category. I’m not nihilist. -

The Mind-Created WorldThe one passage in that entire work that speaks to me is this one:

6.41 The sense of the world must lie outside the world. In the world everything is as it is, and everything happens as it does happen: in it no value exists—and if it did exist, it would have no value.

If there is any value that does have value, it must lie outside the whole sphere of what happens and is the case. For all that happens and is the case is accidental.

What makes it non-accidental cannot lie within the world, since if it did it would itself be accidental.

It must lie outside the world.

As for the rest, I can take it or leave it, but generally the latter. -

The Mind-Created WorldWhat I meant was, the famous last statement in Wittgenstein's Tractatus is often used to smother discussions of certain topics. It certainly is on this forum often enough. I recognise that 'mystical' is often a pejorative term but it's not only that. Discussing the limits of language and logic is a legitimate subject in philosophy, and I don't agree at all that ' the transcendent can mean nothing to us', although it's not an argument I necessarily want to re-open.

-

The Mind-Created WorldThe ancient skeptics were not polar opposites to mystics. Pyrrho of Elis famously sat with the Buddhists of Gandhara and brought back a version of Madhyamika which became Pyrrhonian skepticism. Hence also the resonances between Buddhist philosophy and phenomenology which was central to The Embodied Mind. Francisco Varela took a form of lay ordination in a Buddhist order just before his untimely death.

-

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrong

-

The Mind-Created Worldmysticism being just one more mind created reality — Tom Storm

Insofar as it is mind-created it is delusory. Mysticism proper is seeing through what the mind creates. There’s a term for that in Buddhism, called ‘prapanca’, meaning ‘conceptual proliferation’, detailed in a text delightfully called the Honeyball Sutta. -

The Mind-Created WorldDifferent thing. There’s also a sense in which modern culture normalises philosophical ignorance, lack of insight. I’m not referring to that.

-

The Mind-Created WorldSince we can't access reality, how do we know there is a reality beyond the reality we know? Perhaps it's perspectives all the way down. :wink: — Tom Storm

Well, consider the role of not knowing, of intellectual humility, of ‘all I know is that I know nothing’, of ‘he that knows it, knows it not.’ ‘Accessing reality’ sounds like something you need a swipe card for. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongthe actual existence of things — Janus

But belief in the 'actual existence of things' is precisely what is at stake in the meaning of metaphysical realism. It is exactly what is at issue: you can't know anything of the 'actual existence of things' apart from what your mind enables you to conceive or perceive. You have something in mind when you indicate 'actual things' but you can never actually say what that something is. Not that I want to start yet another of these arguments but I can't just let it go. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongWhat if me and you both existed 8 million years ago and we saw these mountains but had no language. Incapable of it. But now we are: did the mountains exist 8 million years ago? — Apustimelogist

The existence of mountains 8 million years ago, for that matter the entire record of paleontology, comprises empirical facts, which I have no intention of calling into question.

But there are two senses of 'mind-independent' in play. The first is the obvious, commonsense one - that there are all manner of things now and in the past which have existed independently of anyone's knowledge of them. Science and the fossil record tell us that. But the second is more subtle (or more philosophical if you like.) It is drawing attention to the fact that you and I both are possessed of the necessary concepts to understand paleontology, geology, and 'mountains', and '8 million years'. That ability includes, but is not limited to, language. When we gaze out at the external world, or back at the geologically ancient world, we are looking with and through that conceptual apparatus to understand and interpret what we see. That is the sense in which the mountains (or objects generally) are not mind independent. They're mind-independent in an empirical sense, but not in a philosophical sense.

Why is that important? It's important because in a scientific age, what exists independently of any mind, is presumed to be what is real. Philip K. Dick 'reality is what continues to exist when you stop believing in it.' But that overlooks the fact that scientific hypotheses and theories are themselves a web of belief, through which we see the world. (Not just belief, also enormous amounts of data, but that is not relevant to this point.) That doesn't invalidate science or question it's efficacy but it does call into question the instinctive sense that reality is 'mind-independent' in the scientific sense. I say that sense of 'scientific realism' over-values empiricism by imbuing it with a kind of metaphysical certitude that it doesn't possess. And that's what I think 'metaphysical realism', as defined in the reference article, means. -

In defence of the Principle of Sufficient ReasonWhat is the reason for thinking that there must be a reason for what is? — Fooloso4

In Greek philosophy, wasn't that simply a presumption that the world was governed by reason? A kind of intuitive sense that there is a reason for everything as well as every thing - one of the meanings of 'logos' from which we derive logic, and all the other -logies. I don't think it dawned on any philosopher, before the advent of modernity, that the Cosmos - a word meaning 'an ordered whole' - could be anything other than rational. Of course the scientific revolution introduces a wholly different conception of reason as mechanical causation. With the banishing of teleological reasoning the idea of reason in that classical sense fell out of favour.

In the pre-modern vision of things, the cosmos had been seen as an inherently purposive structure of diverse but integrally inseparable rational relations — for instance, the Aristotelian aitia, which are conventionally translated as “causes,” but which are nothing like the uniform material “causes” of the mechanistic philosophy. And so the natural order was seen as a reality already akin to intellect. Hence the mind, rather than an anomalous tenant of an alien universe, was instead the most concentrated and luminous expression of nature’s deepest essence. This is why it could pass with such wanton liberty through the “veil of Isis” and ever deeper into nature’s inner mysteries. — David Bentley Hart

I think the OP, being grounded in Christian philosophy, assumes a similar view. Although it's also interesting that the atheist Schopenhauer grounded his entire philosophy on the 'fourfold root of sufficient reason' and refers to it continually in his writing. Itv was Neitszche who foresaw the sense in which the acid of modernity dissolved the whole idea of cosmic reason. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongthe fact that language didn't exist 8 million years ago doesn't affect the fact that mountains existed 8 million years ago, because the what is the case does not depend on the incidental existence or non-existence of language — Apustimelogist

This has already been mentioned several times but it might help to revisit (comments in italics).

According to metaphysical realism, the world is as it is independent of how humans...take it to be. The objects the world contains, together with their properties and the relations they enter into, fix the world’s nature and these objects [together with the properties they have and the relations they enter into] exist independently of our ability to discover they do. Unless this is so, metaphysical realists argue, none of our beliefs about our world could be objectively true since true beliefs tell us how things are and beliefs are objective when true or false, independently of what anyone might think.

Many philosophers believe metaphysical realism is just plain common sense ( the majority view in my opinion). Others believe it to be a direct implication of modern science, which paints humans as fallible creatures adrift in an inhospitable world not of their making (science as a corrective to fallible ordinary perception, also a majority view)

Nonetheless, metaphysical realism is controversial. Besides the analytic question of what it means to assert that objects exist independently of the mind, metaphysical realism also raises epistemological problems: how can we obtain knowledge of a mind-independent world? There are also prior semantic problems, such as how links are set up between our beliefs and the mind-independent states of affairs they allegedly represent. This is the Representation Problem.

Anti-realists deny the world is mind-independent. Believing the epistemological and semantic problems to be insoluble, they conclude realism must be false. The first anti-realist arguments based on explicitly semantic considerations were advanced by Michael Dummett and Hilary Putnam. — SEP, Challenges to Metaphysical Realism

The position I was arguing for is similar to (although not the same as) Hilary Putnam's 'conceptual relativism': 'Putnam’s Conceptual Relativity Argument: it is senseless to ask what the world contains independently of how we conceive of it, since the objects that exist depend on the conceptual scheme used to classify them.' There's a paper on this here (a Uni of Sydney Honours Thesis.)

All of that is necessary context, in my view, to make sense of why question are being asked about meaning, sentences, propositions and objective facts. -

In defence of the Principle of Sufficient Reason'Being' is a verb. Often overlooked.

-

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongJerrold Katz's Metaphysics of Meaning offers a critique of semantic theories that reduce meaning to empirical and psychological factors. Katz argues that such theories fail to account for the objectivity and normativity of meaning, proposing instead that meaning is rooted in an abstract, non-empirical domain. He draws on the Platonic tradition to frame his argument, suggesting that meanings are akin to abstract objects—like numbers or geometrical shapes—that exist independently of human cognition but are accessible through intellectual apprehension.

Katz's central thesis is that linguistic meaning is a sui generis metaphysical category, irreducible to physical or mental phenomena. He critiques various reductionist approaches, including behaviorism, functionalism, and computational theories of mind, for conflating the properties of meaning with the contingent processes of language use. Instead, Katz advocates for a "realist" theory of meaning, where meanings are intrinsic properties of linguistic expressions and part of an objective semantic reality.

The book also addresses the epistemological implications of this metaphysical stance, arguing that our knowledge of meanings comes through rational intuition rather than sensory perception or introspection. Katz defends this view against charges of metaphysical extravagance, contending that recognizing an abstract domain of meanings is necessary to explain linguistic phenomena like synonymy, ambiguity, and the systematic structure of language.

In essence, Metaphysics of Meaning seeks to establish a rigorous, non-reductive foundation for semantics, challenging contemporary theories that treat meaning as contingent on empirical or psychological processes. Katz's work aligns linguistic theory with a broader philosophical tradition that regards abstract entities as fundamental to understanding reality. -

How to account for subjectivity in an objective world?Given this, we find it impossible to construct a world that is true in any given scenario from all points of view. — bizso09

we place a great deal of emphasis, ordinarily, on the concept of a "fact" as being objective, something independent of individual viewpoints. — J

The whole idea of an absolute objective truth has been radically undermined by science itself. See Ethan Siegel (a popular and hard-headed physics writer):

Space and time might be real, but they’re not objectively real; only real relative to each individual observer or measurer. — Ethan Siegel

He concludes:

It isn’t the job of science, contrary to popular belief, to explain the Universe that we inhabit. Instead, science’s goal is to accurately describe the Universe that we inhabit, and in that it’s been remarkably successful. But the questions that most of us get excited about asking — and we do it by default, without any prompting — often involve figuring out why certain phenomena happen. ...

One such question that we cannot answer is whether there is such a thing as an objective, observer-independent reality. Many of us assume that it does, and we build our interpretations of quantum physics in such ways that they admit an underlying, objective reality. Others don’t make that assumption, and build equally valid interpretations of quantum physics that don’t necessarily have one. All we have to guide us, for better or for worse, is what we can observe and measure. We can physically describe that, successfully, either with or without an objective, observer-independent reality. At this moment in time, it’s up to each of us to decide whether we’d rather add on the philosophically satisfying but physically extraneous notion that “objective reality” is meaningful. -

The Mind-Created Worldwhen I look at your explanation in detail the term "reality" instead seems to refer to "our particular conception of reality", which is amounts to a rather humble claim, not really an attack at all. — goremand

How do you get outside the human conception of reality to see the world as it truly is? That is the probably the question underlying all philosophy. And one aim of the original post was for me to present idealism in a way that isn't understood to mean that the world is all in the mind or the product of the imagination. And it's not an attack on 'realism' per se. It's a criticism of the idea that the criterion for what is real, is what exists independently of the mind, which is a specific (and fallacious) form of realism.

:up: The times certainly are a'changing. -

The Mind-Created WorldTo use Kastrup as an example again, I am convinced that he substantively disagrees with mainstream physicalism. — goremand

As do I, for reasons I have given in the original post, and defended in numerous subsequent entries. -

How to account for subjectivity in an objective world?However, from my point of view, there is a significant difference in the two states. Namely, my identity has changed. In other words, my centre of perception has moved from one person to another. That means that my first person point of view is different, and my whole experience of the world is different, in the two scenarios. Therefore, for me the two scenarios and their respective states of the world are not identical. — bizso09

If, when you underwent this metamorphosis, you also inherited the memories of the new identity, then obviously you wouldn't know anything had happened. Peter would become Alexa, but as far as both are concerned, nothing has happened. If Peter becomes Alexa but retains Peter's memories, then Peter/Alexa would presumably suffer severe cognitive dissonance along the lines of 'who am I?!?' We are indeed differentiated only because our experiences, constitution, location and so on are unique to us. But the primitive sense of 'being a subject' is not unique to any individual. It's only the content associated with that sense which differs.

In conclusion, having both subjectivity and objectivity co-exist in the same world creates a logical contradiction. — bizso09

The claim that this creates a logical contradiction misunderstands the nature of subjectivity. Subjective and objective accounts are not commensurable in the way required to generate a formal contradiction. They operate in different domains of discourse. Objectivity concerns what can be described in third-person terms—facts that are invariant under changes in perspective. Subjectivity concerns the first-person experience, which is inherently tied to a particular point of view, for which perspective is an intrinsic characteristic. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongI think that's near enough to a meaningful consensus. I don't know if I will repeat it, though. I'd like to find another tree to bark up.

-

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongBut the word"empirical" has unnecessary baggage. — Banno

I myself didn't come up with the term 'empirical' nor how it is used in philosophical discourse. 'Empiricism is the philosophical view that all knowledge is based on experience, or that all rationally acceptable beliefs or propositions are justifiable or knowable only through experience.' Any fact of the matter, such as whether there is or is not gold in them thar hills, is an empirical matter which can be resolved by discovery.

The part on which it seems we disagree is that since not just any understanding will do, there is something else that places restrictions on the understanding we construct. — Banno

Admirable clarification. I think the existential factor that I wish to take into account can be stated in a couple of different ways. First, that reality includes the observer. Or put another way, reality is not something we're outside of, or apart from. The reason that is significant, is because the realist view neglects to consider this fact (hence 'subject forgetting himself'). Hence the ever-present implication that the proposition is one thing, the fact another. That has to be embedded in the 'self-other' framework, doesn't it. But that is such an ubiquitous factor in the mind, that we don't see it.

When we say that there is gold at Boorara, we are talking about gold and Boorara, not concept-of-gold and concept-of-Boorara. The very idea of a conceptual schema is problematic... — Banno

So: notice that this differentiation assumes a separation between the observer and the observed. We have the concept, it is in the mind, whereas the object is in the world. But that very distinction is a mental construct, it can only occur to a mind. Self and world, assertion and fact, as separable things. But we are not actually separate from or outside reality. Even Einstein, scientific realist, twigged this:

A human being is a part of the whole, called by us "Universe", a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest — a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. The striving to free oneself from this delusion is the one issue of true religion. Not to nourish the delusion but to try to overcome it is the way to reach the attainable measure of peace of mind.

There is an historical background to this. The advent of modernity, and with it modern philosophy, is inextricably bound up with individualism. I read recently that prior to Descartes, 'ideas' were not something that were not even understood to be the prerogative of the individual mind. But with modern liberalism and individualism, the individual becomes as it were the fulcrum of judgement. With that comes the awareness of separation from the world and others. Hence the 'cartesian anxiety' which 'refers to the notion that, since René Descartes posited his influential form of body-mind dualism, Western civilization has suffered from a longing for ontological certainty, or feeling that scientific methods, and especially the study of the world as a thing separate from ourselves, should be able to lead us to a firm and unchanging knowledge of ourselves and the world around us. The term is named after Descartes because of his well-known emphasis on "mind" as different from "body", "self" as different from "other". (Bernstein Beyond Objectivism and Relativism. This became a theme in the influential book The Embodied MInd, although I encountered it separately through my own discovery.) The key point is, it's a fact about the human condition, not a matter of propositional knowledge as such. That's why I think it is better explored by (not to say explained by) phenomenology and existentialism than analytical philosophy. But I know the response of analytical philosophers is, generally, 'tosh'.

From my perspective, this is because of something they don't see. From their perspective, its because I'm seeing something that isn't there.

One of my now-standard quotations:

From a phenomenological perspective, in everyday life, we see the objects of our experience such as physical objects, other people, and even ideas as simply real and straightforwardly existent. In other words, they are “just there.” We don’t question their existence; we view them as facts.

When we leave our house in the morning, we take the objects we see around us as simply real, factual things—this tree, neighboring buildings, cars, etc. This attitude or perspective, which is usually unrecognized as a perspective, Edmund Husserl terms the “natural attitude” or the “natural theoretical attitude.”

When Husserl uses the word “natural” to describe this attitude, he doesn’t mean that it is “good” (or bad), he means simply that this way of seeing reflects an “everyday” or “ordinary” way of being-in-the-world. When I see the world within this natural attitude, I am solely aware of what is factually present to me. My surrounding world, viewed naturally, is the familiar world, the domain of my everyday life. Why is this a problem?

From a phenomenological perspective, this naturalizing attitude conceals a profound naïveté. Husserl claimed that “being” can never be collapsed entirely into being in the empirical world: any instance of actual being, he argued, is necessarily encountered upon a horizon that encompasses facticity but is larger than facticity. Indeed, the very sense of facts of consciousness as such, from a phenomenological perspective, depends on a wider horizon of consciousness that usually remains unexamined. — The Natural Attitude

Even though Husserl was critical of Kant, you can hear the echo of the Kantian point I keep making about the empirical and transcendental.

Analytical and academic philosophy is not generally existential in that sense. It is professional, cool, detached, impartial. Whereas my attitude is more like this:

Plato was clearly concerned not only with the state of his soul, but also with his relation to the universe at the deepest level. Plato’s metaphysics was not intended to produce merely a detached understanding of reality. His motivation in philosophy was in part to achieve a kind of understanding that would connect him (and therefore every human being) to the whole of reality – intelligibly and if possible satisfyingly. He even seems to have suffered from a version of the more characteristically Judaeo-Christian conviction that we are all miserable sinners, and to have hoped for some form of redemption from philosophy.

The desire for such completion, whether or not one thinks it can be met, is a manifestation of what I am calling 'the religious temperament'. One way in which that desire can be satisfied is through religious belief. Religion plays many roles in human life, but this is one of them. I want to discuss what remains of the desire, or the question, if one believes that a religious response is not available, and whether philosophy can respond to it in another way. — Thomas Nagel, Secular Philosophy and the Religious Temperament -

What's happening in South Korea?South Korea is also an electronics and automotive manufacturing powerhouse.

My reading is, Soon had a very small majority in Parliament, and every move he tried was being blocked by the Opposition, so he basically tried to ride a tank over them, and failed. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongWhen we say that there is gold at Boorara, we are talking about gold and Boorara, not concept-of-gold and concept-of-Boorara. — Banno

You will agree, though, that 'gold at Boorara' is shorthand for 'any empirical fact', right? All of your arguments contra idealism are question-begging, because they're pitched at the wrong level of meaning. You say that the idealist argument denies the reality of empirical fact when it does not. I am not disputing empirical facts.

But there is no reason to suppose that language makes a difference to the gold at Boorara. — Banno

Which you are referring to, and relating to me, who understand what you mean by it, as I already acknowledged.

Previously, you denied that you defend the position described in SEP as 'metaphysical realism'.

According to metaphysical realism, the world is as it is independent of how humans or other inquiring agents take it to be. The objects the world contains, together with their properties and the relations they enter into, fix the world’s nature and these objects [together with the properties they have and the relations they enter into] exist independently of our ability to discover they do.

Where do you disagree with that description? Because it seems to me to describe your view in a nutshell.

The fact that idealism is not well supported in academic philosophy neither surprises nor impresses me. It is contra the zeitgeist, to quote a well-known idealist.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum