-

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismIn any case, it’s unfalsifiable and cannot be proven — NOS4A2

I might agree; realism, idealism, atheism, pantheism, and the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics are all unfalsifiable and cannot be proven.

except when it comes to the science of perception. — NOS4A2

We can look at what follows if we are scientific realists and accept the literal truth of something like the Standard Model and the science of perception. If true, indirect realism follows.

Of course, you can be a scientific instrumentalist and reject the literal truth of the Standard Model and the science of perception if you wish to maintain direct realism, although there may be some conflict in rejecting the literal truth of something that you claim to have direct knowledge of. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI’m not sure there is any good reason for the indirect realist to believe in any of them, since any evidence regarding anything about the external world lies beyond his knowledge. He doesn’t know what he is experiencing indirectly. Hell, he can’t even know that his perception or knowledge is indirect. — NOS4A2

His experience is the evidence. He has direct knowledge of his experiences. What best explains the existence of such experiences and their regularity and predictability? Being embodied within a greater external world, with his experiences being a causal consequence of his interaction with that greater external world.

This is the reasoning that leads one to believe in realism (and so for some direct realism) over idealism. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismGiven that any evidence of the external world lies beyond the veil of perception, or experience, is the realism regarding the external world a leap of faith? — NOS4A2

In a sense, hence why indirect realists claim that there is an epistemological problem of perception, entailing the viability of scepticism.

But the term "faith" is a bit strong. It's no more "faith" than our belief in something like the Big Bang or the Higgs boson is "faith". We have good reasons to believe in them given that they seem to best explain the evidence available to us. The indirect realist claims that we have good reasons to believe in the existence of an external world as it seems to best explain the existence and regularity and predictability of experience. -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realism

It's considered the most parsimonious explanation for the existence and regularity and predictability of experience.

Although subjective idealists disagree.

But given that direct and indirect realists are both realists we can dispense with considering idealism in this discussion. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismWe infer on the basis of evidence and reasoning, but since we only have direct knowledge of experience, we cannot be aware of the evidence of anything outside of it. — NOS4A2

Experience is the evidence. From it we infer the cause. Much like from the screen readings of a Geiger counter we infer the nearby existence of radiation and from reading history textbooks we infer the past existence of a man named Adolf Hitler. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismHow does one know that experience is the causal consequence of his body interacting with the environment if he only has direct knowledge of his own experience, and not of what causes it? — NOS4A2

Inference.

How do we know that a Geiger counter measures ionizing radiation? How do we know that the Higgs boson exists? How do we know that Hitler is responsible for the Holocaust?

Not all knowledge is direct knowledge. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismSorry, you've lost me. You were arguing that indirect realism was the same as non-naive direct realism. You seem to have abandoned that to ask me what it means to say that an experience is "of" some distal object. I answered that and you said that an indirect realist would agree. I'm no longer sure what you are arguing for or where you disagree. — Luke

You said that indirect realism and non-naive direct realism are different positions because non-naive direct realism believes that "my experience is of distal objects" is true and indirect realism believes that "my experience is of distal objects" is false.

But you say that "my experience is of distal objects" means "distal objects are causally responsible for my experience".

Indirect realists believe that "distal objects are causally responsible for my experience" is true.

So given that both indirect realists and non-naive direct realists believe that "distal objects are causally responsible for my experience" is true, what is the difference between being a non-naive direct realist and being an indirect realist?

It seems to be that their only disagreement is over what the phrase "my experience is of distal objects" means. But that's not a philosophical disagreement; that's an irrelevant disagreement about grammar. And a confused one, because there is no 'true' meaning of the phrase "my experience is of distal objects". It just means whatever we use it to mean, and clearly non-naive direct realists and indirect realists are using it in different ways and so to mean different things.

Philosophically, non-naive direct realists and indirect realists are the same: they agree that distal objects are not constituents of experience, although play a causal role, and so that there is an epistemological problem of perception; our knowledge of the external world is indirect, inferred from experience. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI'm trying to make sense of the conclusion that the heater grate six feet to my left is not what I see. — creativesoul

I'm not saying that it's not what you see. I'm saying that distal objects are not constituents of experience. The grammar of "I see X" has nothing do with the epistemological problem of perception, much like the grammar of "the book is about X" has nothing to do with any epistemological problem of a history textbook.

The relevant disagreement between direct and indirect realism concerns whether or not experience provides us with direct knowledge of the external world and its nature. Our scientific understanding is clear on this; it doesn't. Experience is a causal consequence of our body interacting with the environment but our knowledge of that environment is indirect; we make inferences based on our direct knowledge of our own experiences. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismOkay. So then are distal objects mental constituents of experience? — creativesoul

Distal objects are physical objects. What would it mean for a physical object be a mental constituent? -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismIf the indirect realist agrees that some distal object has interacted with one's sense to cause the experience, then I'm not sure what to make of this:

"Experience does not extend beyond the body. Distal objects exist outside the body." — Luke

Why not?

The Sun is physically separate from the grass, but (light from) the Sun has physically interacted with the grass to cause it to grow. It seems pretty straightforward.

Likewise, the apple is physically separate from my sense organs, but (light from) the apple has physically interacted with my sense organs to cause a conscious experience. Also pretty straightforward. -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realism

Yes, distal objects are not physical constituents of experience, which is why knowledge of experience is not direct knowledge of distal objects, hence the epistemological problem of perception. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismAre you saying that none of that counts as a distal object? — creativesoul

I'm saying that distal objects are not constituents of experience, much like Hitler is not a constituent of some book about him. Each are separate entities. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismWhat it means to say that an experience is of some distal object is that the distal object has somehow interacted with one's senses to cause the experience. — Luke

The indirect realist agrees that some distal object has interacted with one's sense to cause the experience. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismIt follows that no constituent of experience extends beyond the body.

Is that about right as well? — creativesoul

Yes. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismNon-naive realists believe that our perceptions can be of distal objects, whereas indirect realists believe that our perceptions are only of mental representations or sense data. — Luke

Experience does not extend beyond the body. Distal objects exist outside the body.

What does it mean to say that some experience is of some distal object? What is the word "of" doing here?

Perhaps you'll find that what non-naive direct realists mean by "of" isn't what indirect realists mean by "of" and that, given their different meanings, both claims are mutually agreeable. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI look out into the distance and see a tree in the yard. There's a squirrel running around the tree, doing its thing. You're claiming that the squirrel and the tree are either not distal objects or - if they are - they are not(cannot be) constituents of experience.

Is that about right? — creativesoul

Yes. Experience does not extend beyond the body. Distal objects exist outside the body. Therefore, distal objects are not constituents of experience.

Experience and distal objects are in a very literal physical sense distinct entities with a very literal physical distance between the two. -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realism

The dispute between direct(/naive) and indirect(/non-naive) realism concerns the epistemological problem of perception; does experience provide us with direct knowledge of the external world?

Direct(/naive) realists believe that experience does provide us with direct knowledge of the external world because they believe that we have direct knowledge of experience and that the external world is a constituent of experience.

Indirect(/non-naive) realists believe that experience does not provide us with direct knowledge of the external world because they believe that we have direct knowledge only of experience and that the external world is not a constituent of experience. Knowledge of the external world is inferential – i.e. indirect – with experience itself being the intermediary through which such inferences are possible.

So-called "non-naive direct realism" is indirect(/non-naive) realism. The addition of the (redefined) word "direct" in the name is an unnecessary confusion, likely arising from a confused misunderstanding of indirect(/non-naive) realism. -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realism

The answer to all of your questions depend on the meaning of the word “direct” which you have already admitted mean different things to the indirect realist and the non-naive direct realist.

According to the indirect realist’s meaning, perception of distal objects is not direct1.

According to the non-naive direct realist’s meaning, perception of distal objects is direct2.

If you replace the word “direct” with each group’s underlying meaning then you’ll probably find that indirect and non-naive direct realists agree with each other, which is why they amount to the same philosophical position regarding the epistemological problem of perception.

Their ‘disagreement’ is over the irrelevant issue of the meaning of the word “direct”. Words just mean what we use them to mean. It’s not like there’s some ‘true’ meaning of the word “direct” that each group is either succeeding or failing to describe. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismAre you saying that distal objects are unnecessary for the response? — creativesoul

Yes. When the visual and auditory cortexes etc. activate without being triggered by some appropriate external stimulus then we are dreaming or hallucinating, but nonetheless seeing and hearing things because the visual and auditory cortexes are active. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI get all that, I just don’t understand how someone can see something without eyes. If sight involves eyes, and those eyes are missing or closed, then is he really seeing?

I don’t think so. In my view the nomenclature is strictly metaphorical, a sort of folk biology, the result of the disconnect between states of feeling and states of affairs. — NOS4A2

Unless we're dealing with technical terms like those in maths and science, the notion that there is some singular "correct" meaning of a word or phrase is wrong. The ordinary uses of "the schizophrenic hears voices", "I see a white and gold dress", and "John feels a pain in his arm" are all perfectly appropriate.

Perhaps better verbs are in order, for instance “I dream of such and such” or “I am hallucinating”. — NOS4A2

Dreams and hallucinations have different perceptual modes, exactly like waking veridical experience. Some schizophrenics see things; others hear things.

As you say, experience doesn’t extend beyond the body, and the indirect realist does not believe the external world is a constituent of his experience. Well what is? — NOS4A2

Smells, tastes, colours, etc.: the things that are the constituents of hallucinations and dreams. The only relevant difference between a waking veridical experience and an hallucination or dream is that waking veridical experiences are a response to some appropriate external stimulus (as determined by what’s normal and useful for the species and individual in question). -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThat’s what I don’t understand. In layman’s terms viewing, seeing, looking etc. involves the eyes. How does one see a representation? — NOS4A2

I can see things when I close my eyes, especially after eating magic mushrooms. The schizophrenic hears voices when suffering from psychosis. We all see and hear and feel things when we dream.

There's more to the meaning of "I experience X" than simply the body responding to external stimulation, else we couldn't make sense of something like "some people see a black and blue dress and others see a white and gold dress when looking at this photo" or "I'm looking at this 'duck-rabbit' picture but I can't see the duck".

Do we experience the external world? The direct realist would say yes, the indirect realist would say no. After answering we can approach the philosophical disagreement. So what’s missing? — NOS4A2

Do we directly experience the external world? The indirect realist accepts that we experience the world; he just claims that the experience isn't direct.

So what is the relevant philosophical meaning of "direct"? It's the one that addresses the epistemological problem of perception (does experience inform us about the nature of the external world) that gave rise to the dispute between direct and indirect realists in the first place. Direct realists claimed that there isn't an epistemological problem because perception is direct, therefore the meaning of "direct" must be such that if perception is direct then there isn't an epistemological problem.

Given that experience does not extend beyond the body and so given that distal objects and their properties are not constituents of experience, and given that experience is the only non-inferential source of information available to rational thought, there is an epistemological problem and so experience of distal objects is not direct. Furthermore, many of the qualities of experience – e.g. smells and tastes and colours – are not properties of distal objects (as modelled by our best scientific theories), further reinforcing the epistemological problem and so indirect realism. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismFor indirect perception, something in the world causes a representation of an apple, which is viewed by something in the brain. — NOS4A2

What does it mean for some A to view some B?

Sometimes you seem to be suggesting that A views B iff A has eyes that respond to light reflecting off B. But then the above is claiming that indirect realists believe that something in my brain has eyes that respond to light reflecting off some representation in my brain. Which is of course nonsense; no indirect realist believes this.

So this would seem to prove that what indirect realists mean by "A sees B" isn't what you mean by "A sees B", and so you're talking past each other.

Perhaps we can formulate it another way. Do we experience “distal objects”? — NOS4A2

That question doesn't address the philosophical disagreement between direct and indirect realism. It's a red herring.

It's like asking "do we kill people?" Yes, we kill people; but we kill people using guns and knives and poison and so on.

So one person says "John didn't kill him; the poison killed him" and the other person says "John killed him (using poison)" and then they both argue that one or the other is wrong. It's a confused disagreement; it's just two people describing things in different but equally valid ways.

This is the confused disagreement that you and others are engaging in when you ask "do we feel distal objects or do we feel mental sensations?". -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThanks, I'll check it out.

I do also want to further reply to this:

Secondly, the indirect realist's insistence on the pure subjectivity of secondary qualities like color is a significant weak point in their view. Pushing this line of argument risks collapsing into an untenable Cartesian dualism, where the "real" world is stripped of all qualitative richness and reduced to mere geometric form.

I believe it's Paul Churchland who argues for eliminative materialism and that pain just is the firing of c-fibers? The same principle might hold for colours: colours just are the firing of certain neurons in the brain. Given that apples don't have neurons they don't have colours (much like they don't have c fibers and so don't have pain). This might "strip" apples of all "qualitative richness" but it doesn't entail anything like Cartesian dualism.

The naive view that projects colours out onto apples is as mistaken as projecting pain out onto fire. It misunderstands what colours actually are. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismDo you think the roundness of the apple merely is a mental property of the human beings (or of their brains) who feel it to be round in their hand? — Pierre-Normand

Roundness as seen or roundness as felt? Because these are two different things. In fact, there have been studies of people born blind who are later given sight and are not able to recognize shapes by look even though they recognize them by feel. They have to learn the association between the two.

So, roundness as seen is a mental phenomenon and roundness as felt is a mental phenomenon. I don't know what "mind-independent" roundness would even be.

This sounds like a form of Berkeleyan idealism since you end up stripping the objects in the world from all of their properties, including their shapes and sizes. — Pierre-Normand

I wouldn't strip them of the properties that the Standard Model or the General Theory of Relativity (or M-Theory, etc.) say they have.

Does not your property dualism threaten to collapse into a form of monistic idealism? — Pierre-Normand

I don't think so. I can continue to be a scientific realist and accept the existence of the substances and properties that our best scientific models talk about. I just accept that these scientific models don't (or even can't) talk about consciousness. Worst case scenario I can be a Kantian and accept the existence of noumena. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismSecondly, the indirect realist's insistence on the pure subjectivity of secondary qualities like color is a significant weak point in their view. Pushing this line of argument risks collapsing into an untenable Cartesian dualism, where the "real" world is stripped of all qualitative richness and reduced to mere geometric form. — Pierre-Normand

I don't think that this is a weakness. I think that this is a fact entailed by scientific realism and the Standard Model. I think that the hard problem of consciousness entails something like property dualism.

Although, this latter point isn't strictly necessary. It is entirely possible that property monism is correct, that mental phenomena is reducible to physical phenomena like brain states, and that colour is a property of brain states and not a property of an apple's surface layer of atoms.

I think that this is clearer to understand if we move on from sight. The almost exclusive preoccupation with photoreception is a detriment to philosophical analysis. Let's consider other modes of experience: sounds, smells, tastes, touch. Is it a "weakness" to "strip" distal objects of these qualities?

I think that direct realists are deceived by the complexity of visual experience into adopting a naive and ultimately mistaken view of the world. I wonder what born-blind philosophers think about direct and indirect realism. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThe non-naive direct realist agrees with the indirect realist that we do not perceive the WAIIII, but does not define direct perception in these terms. For the non-naive direct realist (or for me, at least), direct perception is defined in terms of perceiving the world, not in terms of perceiving behind the appearances of the world to the WAIIII. — Luke

So what you're saying is that what indirect realists mean by "direct" isn't what non-naive direct realists mean by "direct", and so that it is possible that experience isn't "direct" as the indirect realist means by it but is "direct" as the non-naive direct realist means by it, and so that it is possible that both indirect and non-naive direct realism are correct because their positions are not mutually exclusive.

This is the very point I am making. Non-naive direct realism is indirect realism given that they both accept that distal objects and their properties are not constituents of experience, that experience does not inform us about the mind-independent nature of the external world, and so that there is an epistemological problem of perception.

Any "disagreement" between indirect realists and non-naive direct realists is regarding irrelevant issues about grammar (e.g. the meaning of the word "direct").

I'll refer once again to Howard Robinson's Semantic Direct Realism:

The most common form of direct realism is Phenomenological Direct Realism (PDR). PDR is the theory that direct realism consists in unmediated awareness of the external object in the form of unmediated awareness of its relevant properties. I contrast this with Semantic Direct Realism (SDR), the theory that perceptual experience puts you in direct cognitive contact with external objects but does so without the unmediated awareness of the objects’ intrinsic properties invoked by PDR. PDR is what most understand by direct realism. My argument is that, under pressure from the arguments from illusion and hallucination, defenders of intentionalist theories, and even of relational theories, in fact retreat to SDR. I also argue briefly that the sense-datum theory is compatible with SDR and so nothing is gained by adopting either of the more fashionable theories.

Phenomenological Direct Realism is incorrect and Phenomenological Indirect Realism is correct.

Semantic Direct Realism ("I feel myself being stabbed in the back") and Semantic Indirect Realism ("I feel the sensation of pain") are both correct, compatible with one another, and compatible with Phenomenological Indirect Realism. -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realism

That's just reading too much into the grammar. If one person claims that we read words on a page, that the painting is paint, and that we feel a sensation and another person claims that we read about Hitler's rise to power, that the painting is of a landscape, and that we feel being stabbed, arguing that either one or the other set of claims is correct is a complete confusion. They are not mutually exclusive. They are different ways of talking about the same thing.

It's not even clear what the arrows are supposed to represent in your pictures. What physical process does the arrow represent in your picture of direct realism? What physical processes do the arrows represent in your picture of indirect realism? How would you draw a picture of the direct realist and the indirect realist dreaming or hallucinating?

The relevant philosophical difference between direct and indirect realism is that regarding the epistemological problem of perception; are distal objects and their properties constituents of experience and so does experience inform us about the mind-independent nature of the external world. To be a direct realist is to answer "yes" to these questions and to be an indirect realist is to answer "no" to these questions. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismIt appears that you only want to argue against naive realism, which is fine, but I think I've addressed that in my post above. — Luke

I have yet to hear a meaningful description of non-naive direct realism. Every account so far seems to just be indirect realism but refusing to call it so.

If you accept that distal objects are not constituents of experience and so that experience does not inform us about the mind-independent nature of the world then you are accepting indirect realism, because that's all indirect realism is.

The grammatical argument over whether we should say "I feel a sensation" or "I feel a distal object" is irrelevant – and again not mutually exclusive: you can describe it as feeling pain or as feeling your skin burn or as feeling the fire. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismYou don't see the screen; you see sensations? — Luke

Light reflects from the screen, stimulating the sense receptors in the eyes, sending signals to the brain, eliciting a visual sensation. Presumably we all agree on that.

You can call this seeing the screen or you can call this seeing a visual sensation. It makes no difference. That’s simply an irrelevant grammatical convention, and not in fact mutually exclusive.

The relevant philosophical concern is that the visual sensation is distinct from the screen, that the properties of the visual sensation are not the properties of the screen, and that it is the properties of the visual sensation that inform rational understanding, hence why there is an epistemological problem of perception. That’s the indirect realist’s argument. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismAll this seems to be saying is that our body is continually responding to new stimulation, reshaping the neural connections in the brain and moving accordingly. That, alone, says nothing about either direct and indirect realism.

Direct and indirect realism as I understand them have always been concerned with the epistemological problem of perception.

The indirect realist doesn’t claim that we don’t successfully engage with the world. The indirect realist accepts that we can play tennis, read braille, and explore a forest. The indirect realist only claims that the shapes and colours and smells and tastes in experience are mental phenomena, not properties of distal objects, and so the shapes and colours and smells and tastes in experience do not provide us with direct information about the mind-independent nature of the external world. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThis suggests that there is more to the visual phenomenon than just the raw retinal data. There is a sub-personal interpretive or organizational component that structures the experience in one way or another before it is given to conscious experience. — Pierre-Normand

I agree. But it is still the case that all this is happening in our heads. Everything about experience is reducible to the mental/neurological. The colours and sizes and orientations in visual experience; the smells in olfactory experience; the tastes in gustatory experience: none are properties of the distal objects themselves, which exist outside the experience. That, to me, entails the epistemological problem of perception, and so is indirect realism. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismWhy can't distal objects be constituents of experience — creativesoul

Because experience does not extend beyond the body – it’s the body’s physiological response to stimulation (usually; dreams are an exception) – whereas distal objects exist outside the body.

If physical reductionism is true then experience is reducible to something like brain states. What would it mean for distal objects to be constituents of brain states?

If property dualism is true then experience is something like a mental phenomenon that supervenes on brain states. What would it mean for distal objects to be constituents of mental phenomena that supervene on brain states?

For distal objects to be constituents of experience it would require that experience literally extends beyond the body to encompass distal objects. I accept that this is how things seem to be, and it's certainly how I ordinarily take things to be in everyday life, but this naïve view is at odds with our scientific understanding of the world.

Direct realism would seem to require a rejection of scientific realism, and presumably an acceptance of either substance dualism or objective idealism.

I think that you've given indirect realism too much credit. I see no reason to think that if colors are not inherent properties of distal objects that the only other alternative explanation is the indirect realist one. They can both be wrong about color. — creativesoul

If colour is experienced but not a property of distal objects then it must be a property of the experience itself. I don't see how there can be a third option. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismWith the phrase "visually appears to grow" I refer to the visual information about an objective increase in the dimensions of an object. — Pierre-Normand

The visual phenomenon grows (as shown by comparing it to the ruler held at arm's length from my face). If you infer from this that some distal object grows then you may have made a false inference.

But at least we've established the distinction between the visual phenomenon and the distal object. The visual phenomenon grows, the distal object doesn't, therefore the visual phenomenon is not the distal object.

We've also established the distinction between perception and inference. The inference (about the distal object) may be correct or incorrect, but the perception just is what it is (neither correct nor incorrect). It's not the case that given this distance from the object this is the size it should appear such that if I look at it through a pair of thick glasses then its increased size (relative to not wearing glasses) is an "illusion".

Perhaps also relevant is this experiment:

We are in an empty black room, looking at a wall. Two circles appear on the wall. One of the circles is going to grow in size and the other circle is going to move towards us (e.g. the wall panel moves towards us). The rate at which one grows and the rate at which the other moves towards us is such that from our perspective the top and bottom of the circles are always parallel.

Two different external behaviours are causing the same visual phenomenon (a growing circle). It's impossible to visually distinguish which distal object is growing and which is moving towards us. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismAnd to repeat something I said earlier: indirect realism does not entail unsuccessful interaction with the world, and so successful interaction with the world does not entail direct perception.

Therefore, "direct perception" cannot be defined in terms of successful interaction with the world. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismDo you believe that naive/direct realism cannot deny color as a property of objects? — creativesoul

I think that if they admit that colours are not properties of objects then they must admit that colours are the exact mental intermediary (e.g. sense-data or qualia or whatever) that indirect realists claim exist and are seen. And the same for smells and tastes.

So how is their position not indirect realism?

Direct realists claimed that there is no epistemological problem of perception because distal objects are actual constituents of experience. Indirect realists claimed that there is an epistemological problem of perception because distal objects are not actual constituents of experience (and that the actual constituents of experience are something like sense-data or qualia or whatever).

Now we have so-called "direct" realists who seem to accept that distal objects are not actual constituents of experience (and so accept that something else must be) but still claim to be "direct" realists, which seems to have simply redefined the meaning of "direct" into meaninglessness and doesn't appear at all opposed to indirect realism.

To me, it's simple: experience is constituted of mental phenomena, not distal objects. The mental phenomena that constitute experience is what directly informs our understanding, and so there is an epistemological problem of perception. "Indirect realism" is the most appropriate label for this. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismWhen you are hanging upside down, the flower pot sitting on the floor may momentarily appear as if it is inverted and stuck to the ceiling. — Pierre-Normand

It doesn't appear as if it's stuck to the ceiling. It appears as if the floor is up and the ceiling is down, which they are.

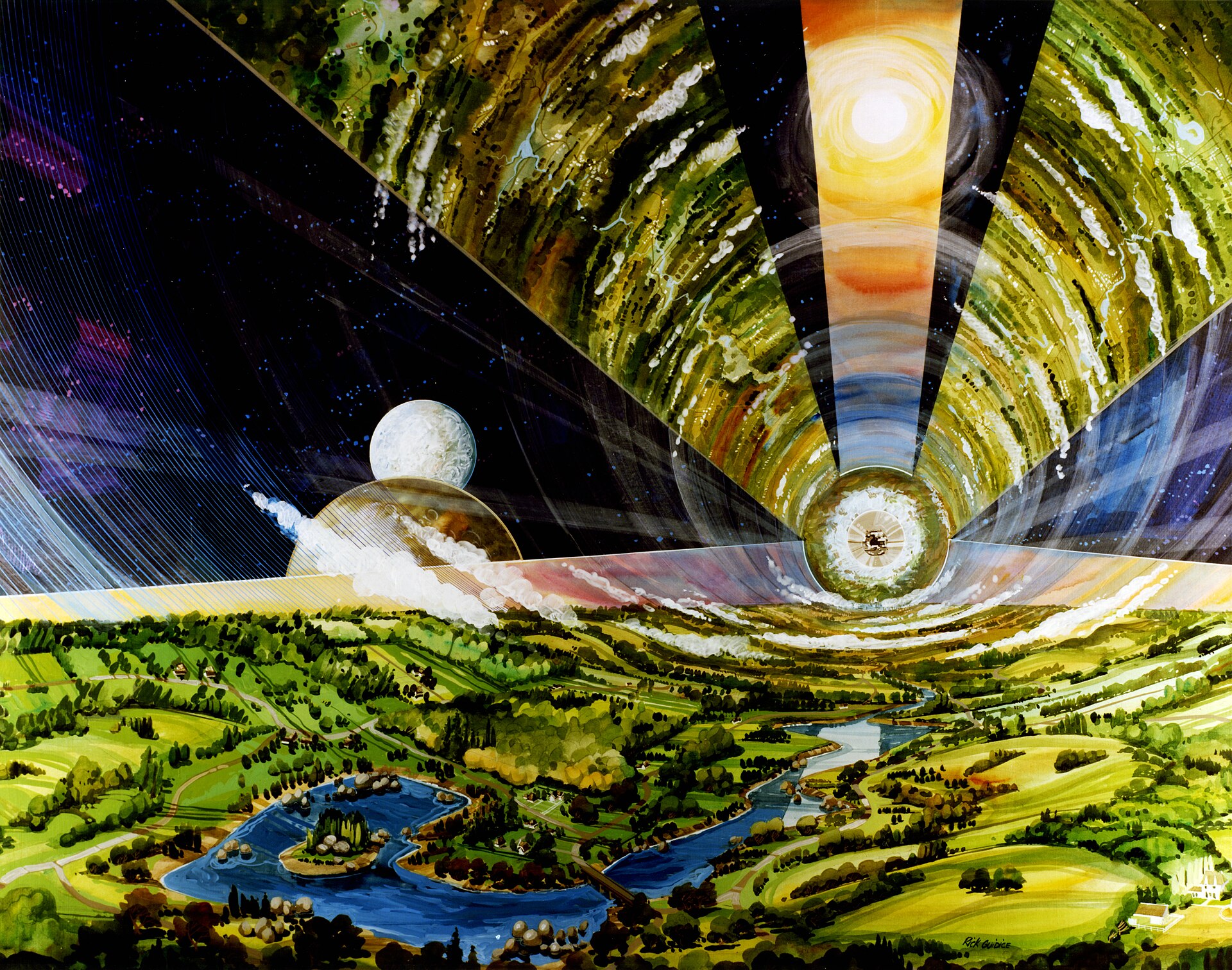

As you seem to think that gravity is relevant, I refer you again to an O'Neill cylinder:

There are three liveable "islands", each with their own artificial gravity. It is not the case that those living on Island 1 are seeing the world the "right way up" and those living on Islands 2 and 3 are seeing the world "the wrong way up" or vice versa.

And imagine someone were to use a jetpack to lift towards another island (and eventually fall towards it when they are sufficiently close to be affected by its gravity), maintaining their bodily orientation (i.e. head-first towards the other island's ground). At which point do you claim their visual orientation changes from "veridical" to "illusory"? The moment the other island's artificial gravity is sufficiently strong to pull them in?

Suppose you are walking towards a house. As your distance from it is reduced by half, the house doesn't visually appear to have grown twice as large. — Pierre-Normand

This is ambiguous. The visual appearance of the house certainly has gotten bigger. I can test this by holding a ruler at arm's length from my face as I walk towards the house. When I start walking the bottom of the house is parallel to the 10mm mark and the top of the house is parallel to the 20mm mark. As I walk towards the house the bottom becomes parallel to the 0mm mark and the top becomes parallel to the 30mm mark.

I'm not sure what other meaning of "visually appears to grow" you might mean. I accept that the house doesn't appear to have new bricks added into its walls or anything like that, but then I don't think anyone claims otherwise.

Or rather than walking towards the house, let's say I look through a pair of binoculars. Which of my ordinary eyesight and my binocular-enhanced vision shows the "correct" size of the house?

Much like visual orientation, visual size is also subjective. There's no "correct" orientation and no "correct" size. There's just the apparent orientation and apparent size given the individual's biology.

Some organism when standing on the ground may see with its naked eyes what I see when hanging upside down and looking through a pair of red-tinted binoculars. Neither point of view is more "correct" than the other. Neither point of view is illusory. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThe eyes are active; they seek out and use the light, transducing it, converting it to signals for use by the rest of the body, in a similar way you mention. My guess is indirect realists do not consider such an act as an act of perception because it doesn't involve a mediating factor. — NOS4A2

They agree that the eyes move about their sockets and in response to stimulation by electromagnetic radiation send signals to the brain, which in turn sends signals to the muscles.

But like many direct realists (and unlike you) they also believe in first-person experience, and perception is related to this rather than just the body's unconscious response to stimulation. Flowers react to light from the Sun but they don't see anything because they're not conscious.

The traditional disagreement between direct and indirect realists concerns the phenomenology of first-person experience and its relationship to distal objects. The direct realist believes that this relationship is constitutive (entailing such things as the naive theory of colour), whereas the indirect realist believes that it is only causal (and so those things which are constituents of the experience are the intermediary). -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI am a direct realist and do not believe distal objects and their properties are actual constituents of the experience. — NOS4A2

Then I don't know what you mean by "direct".

If both "direct" and indirect realists agree that distal objects and their properties are not actual constituents of the experience then what are they disagreeing about?

I try my best to make sense of the argument, but so far "experience" appears to be a roundabout way of describing the body, at least metaphorically.

So let's just examine the raw physics. There is a ball of plasma 150,000,000 km away. It emits electromagnetic radiation. This radiation stimulates the sense receptors in some organism's sense organ. These sense receptors send electrical signals to the brain and clusters of neurotransmitters activate, sending signals to the muscles causing the organism to move.

What do direct realists believe is happening here that indirect realists don't believe, or vice versa?

And to bring back in our ordinary way of describing this, what does "I see the Sun" mean? Specifically, what do the words "I" and "see" refer to? When we say "my experience is of the Sun" what does the word "experience" refer to and what is the word "of" doing? Everyone agrees that the body reacts to stimulation by electromagnetic radiation originating from the Sun, but direct and indirect realists are presumably disagreeing about something? -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismBut there are epistemological problems with indirect realism, and they are insurmountable. If one is privy only to his experience, or representation, whatever the case may be, how can he know whether they represent the real world? — NOS4A2

That's the point. Indirect realists believe that there is an epistemological problem precisely because the only information given directly to rational thought is the body's reaction to stimulation.

Direct realists believed that there isn't an epistemological problem because distal objects and their properties are actual constituents of the experience (and not just causes), and so entails things like the naive realist theory of colour. That's what it means for perception to be direct. But this view of the world was proven wrong by modern science.

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum