-

Commandment of the AgnosticThis original post brings a certain mild misery to me, to be stirring up mischief through slave morality is cute, but altogether misguided. — Vaskane

Ya know how autistic people tend to focus narrowly on one thing... -

A Normative Ethical Dilemma: The One's Who Walk Away from OmelasI presume

The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas

is still under copyright, so I won't post a link. However, a quick copy and paste and Google will turn up lots of sites hosting pdf copies.

It is very short, and very well worth reading. -

A Digital Physics Argument for the existence of God3. Quantum cognition and decision theory have shown that information processing in a mind exhibits quantum principles — Hallucinogen

Citation? -

The Necessity of Genetic Components in Personal IdentityIf knowledge and memory is also embedded in this momentarily unfolding flux then is there a fact of the matter about being the same as I was 5 minutes ago? After all, to generate the right expressions of memory or knowledge only requires the right momentary states in terms of physical states of my neuronal membranes. Continuity is not necessary and it is questionable whether my brain is ever in the same two states even for similar experiences at different times. — Apustimelogist

Right. Perdurance seems to me a more realistic way of looking at identity. -

The Necessity of Genetic Components in Personal IdentityThis whole thread is a case of overreach by the thought police. — unenlightened

Is this meant seriously? If so, it seems like a bizarre reaction to the thread to me. -

Are words more than their symbols?Although I am also a visual artist, I cannot see internal images; meaning I cannot invoke a picture of anything like a photograph and examine it like I would a photograph. — Janus

I found this bit of the article I linked particularly interesting:

She explains that deaf people tend to experience the inner voice visually. “They don’t hear the inner voice, but can produce inner language by visualising hand signs, or seeing lip movements,” Loevenbruck says. “It just looks like hand signing really,” agrees Dr Giordon Stark, a 31-year-old researcher from Santa Cruz. Stark is deaf, and communicates using sign language.

His inner voice is a pair of hands signing words, in his brain. “The hands aren’t usually connected to anything,” Stark says. “Once in a while, I see a face.” If Stark needs to remind himself to buy milk, he signs the word “milk” in his brain. Stark didn’t always see his inner voice: he only learned sign language seven years ago (before then, he used oral methods of communication). “I heard my inner voice before then,” he says. “It sounded like a voice that wasn’t mine, or particularly clear to me.” -

Are words more than their symbols?I don't recall seeing a link in the thread to an article on the experience of an inner voices, so...

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2021/oct/25/the-last-great-mystery-of-the-mind-meet-the-people-who-have-unusual-or-non-existent-inner-voices

I'm towards the nonexistent inner voice side of things myself. Though I can relate to experiencing an inner voice to some extent, it's not an aspect of my normal experience, let alone something that seems necessary for thought in my experience. -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismYour argument was that contradictions inevitably occur, and therefore they are not bad. Wounds also inevitably occur. Are they bad? Should they be avoided? Should we apply bandage and salve, or leave them to fester? — Leontiskos

I already said that there is practical value to resolving one's contradictory beliefs. However, it is no more an indication of moral badness to find that one holds contradictory beliefs than it is an indication of moral badness to find that one has been wounded.

It is simply a consequence of having an evolved brain, that develops intuitions in response to the limited evidence/training available to each individual to learn from, that results in fallible humans having conflicting intuitions. Sure ongoing learning, like bodily hygiene, is practically valuable. However, morally judging people for not being omniscient seems more than a tad unreasonable to me. Do you agree? -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismI don't think you managed to address it at all. Do you believe that we ought not hold contradictory positions, or do you disagree? — Leontiskos

I don't think there is any moral fact of the matter, though there is certainly pragmatic value in continually wiping the mirror.

I don't think you have considered what I proposed seriously enough. (Although understandably it's likely to take some time for you to develop some relevant recognitions.) I recommend looking into Zen for some useful tools for breaking down weakly trained intuitions.

One thing I think might be worth considering, is the way that you yourself have just demonstrated the monkey mindedness I was referring to. Another is your propensity for jumping to conclusions.

Fair warning, I spent the prior 15 years as a regular atheist poster on William Lane Craig's (now shuttered) forum. Here's a thread you might find surprisingly educational:

Does being in a blaming state of mind amount to Monkey Mindedness? -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismI see the atheist trolls have arrived (↪wonderer1, ↪Joshs). — Leontiskos

Ah, the warm glow of Christian love.

Anyway, I gave a serious response to your question. What do you think? -

The Necessity of Genetic Components in Personal IdentitySo maybe I considered moving the bishop and decided to do something else. When I did something else, it was no longer possible. But it was possible when I considered it. Surely? — Ludwig V

Epistemically possible? Sure.

Metaphysically possible? I don't know of any good reason to think so. -

Project Q*, OpenAI, the Chinese Room, and AGII thought some might be interested in this:

https://spectrum.ieee.org/ai-energy-consumption

You are a bad man @Wayfarer - using Chat-GPT so profligately. :razz: -

The Necessity of Genetic Components in Personal IdentityWhat is being made clear is that it is very easy to get confused between the imagination and the real, and this is because imagination is in use all the time to model and predict the world as it unfolds. — unenlightened

:up: -

The Necessity of Genetic Components in Personal IdentityI'm a bit confused, now, as to what we're disagreeing upon because I thought I had said some fairly sensible things, but it seems not to be clicking. — Moliere

I expect the lack of 'clicking' is mostly a matter of me trying to get by without providing enough details. The point I was hoping to get across was that the role that gamete roulette plays in neurological differences, while for practical purposes invisible (by comparison with say, hair color), is on a whole nother level in determining what it means to be the individual result of the spin of the wheel.

I don't want to go in depth in trying to make a case, but some additional info on my basis for thinking so...

https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/patient-caregiver-education/brain-basics-genes-work-brainAt least a third of the approximately 20,000 different genes that make up the human genome are active (expressed) primarily in the brain. This is the highest proportion of genes expressed in any part of the body. These genes influence the development and function of the brain, and ultimately control how we move, think, feel, and behave. -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismDo you think it is a moral failure for people to have inconsistent beliefs?

— wonderer1

"Things which we know (or believe) to be bad or evil are things that we know we oughtn't do." We know it is bad or evil to simultaneously hold contradictory propositions, and therefore we know we ought not do so. Whether one wants to call this a moral failure will depend on their definition of moral. I have given two definitions, one which would apply and one which would not.

What do you think? — Leontiskos

I think evil is in the eye of the beholder, in that evil is something our evolved monkey minds tend to project on things in the world. The notion of a HUD, where things which aren't actually part of the world get projected on top of more straightforward perceptions, might help illustrate this notion.

As we social primates do, in the heat of the moment I'm prone to see people as evil and act on the basis of such mental projections. However in this era, where dishing out the law of the jungle is seldom well advised, I think it is generally better to recognize one's mental projection of evil, for the monkey mindedness that it is, and try to achieve a more enlightened perspective. If I am able to step back from seeing red and recognize my projection of evil for what it is, I tend to be able to act in a more productive way.

Contrary to your claim that, "We know it is bad or evil to simultaneously hold contradictory propositions, and therefore we know we ought not do so.", I understand that it is simply an aspect of human learning that we will often find ourselves holding contradictory propositions. It doesn't make much sense to see oneself as evil for exemplifying such a human characteristic. Of course it is valuable to resolve self contradictory beliefs to the extent one is able, but that hardly makes a person with unresolved self contradictions evil.

― Ralph Waldo Emerson, Self-Reliance: An Excerpt from Collected Essays, First SeriesA foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines. With consistency a great soul has simply nothing to do. He may as well concern himself with his shadow on the wall. Speak what you think now in hard words, and to-morrow speak what to-morrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict every thing you said to-day. — 'Ah, so you shall be sure to be misunderstood.' — Is it so bad, then, to be misunderstood? Pythagoras was misunderstood, and Socrates, and Jesus, and Luther, and Copernicus, and Galileo, and Newton, and every pure and wise spirit that ever took flesh. To be great is to be misunderstood. -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismI would say that in the realm of speculative reason there is the law of non-contradiction, which no one directly denies, but which they do indirectly deny. Are we obliged to obey the law of non-contradiction? Yes, I think so... — Leontiskos

Do you think it is a moral failure for people to have inconsistent beliefs? -

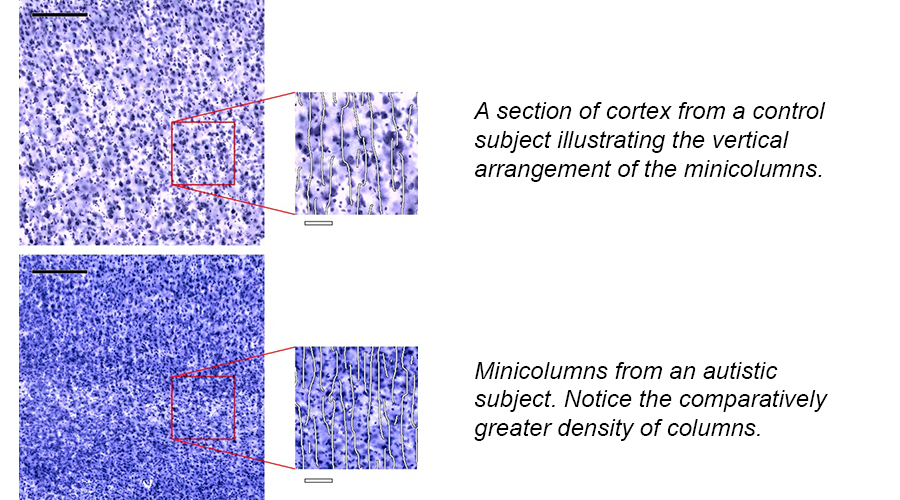

The Necessity of Genetic Components in Personal Identity

I don't have any clear idea of your theory of mind, and I don't expect the points I raise to get much traction in the minds of people unable to seriously consider physicalism. However, my point is that individual variation, that might be seen as being on the order of the variation in fingerprints, can have profound effects in the case of the 'wiring' of our brains. Furthermore the idiosyncracies to brain wiring play a huge role in who we are.

For example, consider these two images, where the difference might appear as superficial as that between fingerprints:

I speak from experience in saying that sort of difference has a profound effect on who one is. Of course I understand most people can get away with being blissfully ignorant of how their own idiosyncratic neural wiring results in them being who they are, but such naivete is not an option for me. And I don't have to make it easy for others to remain naive. :wink:

Edit: Image Source - https://autismsciencefoundation.wordpress.com/2015/08/30/minicolumns-autism-and-age-what-it-means-for-people-with-autism/ -

The Necessity of Genetic Components in Personal IdentityMaybe our understanding of necessity differs? To my mind if you can switch a part of the code and have the same results then there is not a necessary relationship between code and an organism's identity. Since you can do that -- not in science fiction but in science -- it just doesn't strike me as something I'd call necessary for personal identity. That is I can see it plausible that if I had a different code I could still be the same person in a counter-factual scenario because I don't think identity is necessitated by code. It would depend upon which part of the code was switched -- I could also have a genetic disease due to this, for instance, and I'd say I'm a different person then. But if one base got switched out in an intron then that is a scenario that seems plausible to me to possibly make no difference in the course of my life, and in relation to the topic, for my personal identity. — Moliere

Sure there are possible different genetic codes that result in the same phenotype, but the scenario under consideration here is not one of minimal DNA substitution, but of relatively wide spread differences in DNA resulting from random selection of gametes.

Consider the uniqueness of the fingerprints of siblings.

Regarding the uniqueness of brains:

With our study we were able to confirm that the structure of people's brains is very individual," says Lutz Jäncke on the findings.

"The combination of genetic and non-genetic influences clearly affects not only the functioning of the brain, but also its anatomy. -

The Necessity of Genetic Components in Personal Identity

Like many others here, I can't make much sense of the things you say, and I would have to recommend that you talk to a neuropsycholgist about that. -

Is Philosophy still Relevant?This can enter into an utterly different direction. My sole contention has been that the empirical sciences - again, which utilize the scientific method - cannot address what value is, this even in principle. — javra

Suppose "value" is a fallacious reification, and instead there is only valuing as a process that occurs. Could science study human valuing? -

The Necessity of Genetic Components in Personal IdentityCopied from the other thread:

I could have fair hair and still be me. I could be six inches shorter than I am and still be me. I could have musical talent as opposed to competence and still be me. Minor changes don't matter. — Ludwig V

I'd think you can only imagine being yourself with such supeficial changes, but what about less obvious, but more profound differences? Suppose the genes this 'alternate you' got resulted in a person with an IQ 40 points lower than yours? Suppose the genes alternate you got resulted in schizophrenia? Would

you think the alternate you to be you in that case? -

The Philosophy of 'Risk': How is it Used and, How is it Abused?What's with this categorization? Is there a name for a philosophical study of "mean old people"? — jgill

I propose "curmudgeonlogy". -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismSo we have:

1. Moral sentences are not truth-apt (non-cognitivism), or

2. It is not wrong to eat babies (error theory), or

3. It would not be wrong to eat babies if everyone said so (subjectivism), or

4. It would be wrong to eat babies even if everyone said otherwise (realism) — Michael

5. It's a lot more fun to play with babies than to eat them. (emotivism) -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)It should be easy for you to explain why I’m on it. You told me you saw a pattern. — NOS4A2

I've got better things to do. -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?What your comment says to me is that the company I keep in philosophy of science and cognitive science is far removed from your neck of the woods. — Joshs

True, I haven't spent nearly so much time in an ivory tower playing make believe.

Sorry to break it to you, but you really don't know what you are talking about, in describing science. You might as well be telling a fairy tale. -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?Putting it in your terms, how science chose to experience the things became the basis of what the things were in themselves. — Joshs

This says to me that you don't have enough experience in engaging in scientific processes to know what you are talking about. It sounds like you have simply accepted a story about science. What basis do you have, for thinking people should believe that you know what you are talking about on this subject? -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)

If you are not on that spectrum it should be an easy matter for you to read up on the pattern and explain how it doesn't fit. Why would you need any help from me in that regard? -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismIf moral facts are brute facts then there is no explanation. — Michael

The thing is, there are areas of research pointing to there being explanations beyond mere brute fact. See Jon Haidt's The Rightous Mind. There is value in understanding one's tendencies to moral judgement in order to deal with those tendencies skillfully. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)I’m afraid we’ve never met so your intuitions amount to nothing. — NOS4A2

Right, meeting you has nothing to do with the basis by which my intuitions formed. However, I have had previous experiences which led to me having good recognition of the pattern. You aren't providing any reason to think that the pattern doesn't fit. Do you think you are able to? -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Let me know when the real world enters the picture. — NOS4A2

The real world has been in the picture throughout our discusssion.

I was curious as to whether you would falsify my intuition that you are on the psychopathy spectrum, and I provided you with multiple opportunities for you to provide evidence falsifying that hypothesis.

...perhaps I give you too much credit by implying that you are capable of doing this. — Fooloso4

Seems likely to me. (Although I don't think "credit" or "discredit" are necessarily relevant.) -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)The word does not strike a chord, nor can any other abstraction you can put forward. — NOS4A2

Well, you can say that for you it does not strike a chord, but you don't speak for everyone.

You won’t tell me which “us” you’re referring to... — NOS4A2

You didn't ask.

In the context of this thread, the "We the People" discussed in the preamble to the US constitution seems a relevant circle of who one might consider "us". Though I had no particular circle in mind. Some might associate "us" with family, and others with humanity, and draw the circle narrower or wider at different times, depending on circumstances.

Whatever monkeysphere you can relate to will do for the purposes of this discussion.

...proving to me it lacks any reference to the real world and flesh-and-blood human beings. — NOS4A2

You seriously need to improve your critical thinking skills. You mistake jumping to a conclusion on your part for something having been proven. I recommend greater recognition of seeking falsification as good epistemic practice.

Once again, you didn't ask.

Do you still need me to explain references to the real world further? -

Project Q*, OpenAI, the Chinese Room, and AGIReady or not, here it comes. — Jonathan Waskan

Indeed. -

Project Q*, OpenAI, the Chinese Room, and AGIFor some reason ChatGPT also wasn't being fed current information (I think everything was at least a year old). Recently they allowed it access to current events, but I think that's only for paid members. Not sure what the rationale behind the dated info was or is. — Jonathan Waskan

I would guess vetting of sources for reliability would be a concern. What sources of infomation is a 'real time up to date' AI relying on without vetting? -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)If by “strikes primal chords” you mean you get a little tingly sensation whenever you hear a first-person plural or first-person possessives, without first wondering what this “us” refers to... — NOS4A2

You can strike everything after "If" because it is just sophist propaganda spewing out of your head, whether intentionally so or not. A more interesting topic to me is whether or not you can relate to "us" striking a chord. Or to what degree you can do so?

I’d say you’re susceptible all types of propaganda. — NOS4A2

First off, as you demonstrate over and over in this thread alone, you are enormously susceptible to propaganda yourself. So now that we've established that we are humans here discussing things in this thread... Do you experience thoughts of "us" as striking a primal chord within you? -

Project Q*, OpenAI, the Chinese Room, and AGII'm hoping they put the brains and brawn together within the next ten years. — Jonathan Waskan

I'm somewhat trepidatious about it. The first thing that popped up when I googled "neuromorphic hardware" was this link sponsored on Google by Intel. It is the first advertising of neuromorphic hardware that I have seen.

I've been a convinced connectionist for nearly 40 years now, and I was confident that AI would get to the state it is now about now. However, for a long time I thought it would only be after neuromorphic hardware was readily available. The acceleration in the development of AI, that I see as being likely, seems like something humanity is not well prepared for. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)This merits its own consideration:

Why do you keep saying “our democracy”? Why not just say “democracy”? We know the answer: this trite phrase is political language, not used to discuss the concept, but used to appeal emotionally to those who read it. This is what “thinking in words” gets you, an over-estimation of the power of words and the attempts at propaganda as a result. — NOS4A2

It also merits consideration that "us" strikes primal chords, in homo sapiens who aren't psychopathic to some degree. Any thoughts on that? -

Project Q*, OpenAI, the Chinese Room, and AGIIn fact, though Asimov used the three laws to describe robot operating principles, he didn't think of them as being written out explicitly in some form of code. Rather, they were deeply embedded in their positronic networks much as we see with ChatGPT. — Jonathan Waskan

Hopefully not as they are embedded in our neural networks, with an ethical bias towards *us* not being harmed. (With "us" referring to some subset of sentient beings.)

wonderer1

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum