-

A Reversion to Aristotle

"Happiness" is the common translation for the Greek term eudaimonia used by Aristotle. It's not a great translation. Eudaimonia could also be translated as "flourishing" or "living a good life." So:

I don't know . . . possibly I've hung out with the wrong people but the idea that "humans necessarily want to be happy" is extremely implausible to me. Here, for instance, is a person named Pat. Pat suffers from a variety of psychological, physical, and spiritual maladies that produce a kind of chronic frustration, depression, resentment, and lack of ease -- in short, what we mean by "unhappiness." If you ask Pat if they "want to be happy," the answer you will get is: "Nonsense. What you call 'being happy' is for sheep. I operate on a higher plane. Of course I'm miserable, but that is what happens when a person of true intellect sees the world aright. I wouldn't trade one minute of my unhappiness for a fool's paradise of Smiley Faces." Pat, you could say, would rather be Happy (their sense) than happy, but surely that's stretching what "happy" means. Let's face it: Pat just doesn't want to be happy, and they can give you their reasons why.

Pat clearly thinks he is pursuing some higher good here. He thinks happiness, which seems to be taken as "pleasantness" is not conducive to true human flourishing. That's exactly what many later monastic/ascetic commentators on Aristotle have thought as well; true flourishing implies a victory over the body and its pleasures (or something like that). Indeed, he sounds not unlike Aristotle, who calls the life pursuing simple pleasure a "life for grazing animals," (although Aristotle is more sanguine about pleasure generally).

The point is that people pursue some good when they act unless action is to be completely arbitrary. We can't have an infinite regress of motivations. People can, of course, pursue counterfeit goods, disordered goods, or merely relative goods. The ethics is about how to avoid this.

Even Milton's Satan acknowledges this with: "evil be thou now my good." It doesn't make sense to say "evil be evil for me me," if you're going to pursue it.

Robbie's behavior seems pretty well summed up in the Ethic's discussions on virtue versus vice and incontinence. It is not the case that Aristotle thinks we always prefer virtue. One can fall into vice. One can also recognize vice as vice and still prefer it, even as one knows they should try to rise to virtue. When a person is unsuccessful at overcoming desires they know are wrong this is incontinence, whereas if they do the virtuous thing but do not enjoy it they are merely continent. But for Aristotle it is possible, with time and proper education, to come to love virtue and hate vice.

I should note though that his use of vice is very different from today's, which recalls mostly drugs, gambling, etc. For Aristotle virtue is a golden mean between extremes, so rashness or cowardliness are vices, whereas courage is a virtue. Profligacy and grasping are vices, whereas generosity is a virtue, etc. -

A Reversion to AristotleTo return on topic, I think objections 1 and 2 ultimately stem from the modern tendency to only view theoretical reason or "objective knowledge" as fully legitimate. Telos is cast aside because final causation is most easily thought of in terms of practical reason*, whereas the is-ought gap only exists under the tyranny of the "objective." (Like I said, the third objection I don't see as actually following from Aristotle's philosophy.)

Now one powerful response to this sort of tyranny of the objective is Kierkegaard's view that it is ultimately the subjective that has any relevance to our lives. I won't try to summarize this, since I figure many may already be familiar with it. I did find a free anthology of his work here: https://web.archive.org/web/20230514232930/http://www.naturalthinker.net/trl/texts/Kierkegaard,Soren/Provocations.pdf

Sections 15 and 19, both of which are quite short, offer up the core argument against the "obsession with the objective."

I am skeptical of the way in which he sets the two against each other, but I do think it is instructive. I think the two "types of reflection" (subjective/objective) are intricately connected and always inform and mutually co-constitute one another. They are part of a unified, catholic whole, reason as the Logos in which "all things hold together." Without the contents of theoretical, objective reason, the striving of practical reason towards the Good becomes contentless. That said, his argument isn't without merit. If one type of reason should be held up above the other, we have probably picked the wrong one.

So ultimately, I think Kierkegaard's solution risks falling into a sort of pernicious fideism that risks even making the Good (God) set forever out of reach by a sort of all encompassing equivocity (something he tries to fix, but doesn't IMO diffuse). However, it's worth bringing up because it's a popular and powerful critique of modernity.

* Of course, telos is also seemingly indispensable so it gets resurrected in biology as "function," shows up in physics as "constraints," and then shows up in economics and the other social sciences as "utility," "well-being." But often these have to be instrumentalized in order to fit under the tyranny of the theoretical. Thus you end up with the absurdity of policymakers and doctors advocating for certain sorts of interventions "because they are associated with 'self-reported well-being,'" as if the goal was to change how people respond to surveys and not to change how they live.

You could have said the same thing vis-á-vis serfdom at the peak of the industrial revolution. Yet while it certainly would have been true that the abolishment of serfdom was a very positive step forward, it's far from clear that this offset the alienation of people from their labor, massive increase in hunger, and general collapse of social institutions that prevailed among the lower classes in that time period (nor the massive wars and colonial projects motivated by the same era defining forces).

I don't think the thesis that society is experiencing decay in some important aspects can be easily written off by pointing to progress in other areas. -

A Reversion to Aristotle

Statistics are a tool to be abused by whoever uses them, distorted by whoever makes them.

Yes, you seem to be making that point quite well with the move to religious terrorism, just gun violence in Sweden (also an outlier, and at any rate my home town of 150,000 people had around that many gun homicides in a year plenty of times), and sexual violence, which has indeed been on the rise, although this is generally explained by people being vastly more likely to report it than in prior decades.

As to music, this is sort of comical. I don't think it's possible to get any more sexually explicit than 2 Live Crew's hits like "Pop that Pussy," or something like Notorious BIG's "Unbelievable." White Zombie's 1995 hit single "More Human Than a Human," literally opens with a clip from a porno, and Nine Inch Nails 1994 hit "Closer" was all over the radio when I was growing up. At the very least, MTV's "The Jersey Shore," maxed us out on hedonistic degeneracy many years ago, lol. -

A Reversion to Aristotle

I think Bob is pointing to moral decay, which might itself exist along other elements of positive growth. For example, in A Brave New World we see a picture of a society that would surely get extremely high marks on virtually every metric by which modern technocrats tend to evaluate policy "success." Crime is largely a non-issue, there is no poverty, self-reported well being is surely quite high, and technology has allowed for a great deal of comfort, even largely removing the symptoms of aging. But at the same time it seems fair to say that such a society, despite these positive attributes, has slipped into the direst form of moral and ethical decay.

And there are aspects in which the trajectory of society since Huxley's time has followed his dystopian vision, even as it generally still fails to deliver on at least the "pleasure" part of the equation. -

A Reversion to Aristotle

Exactly. Certainly, Nietzsche has been influential. He seems to sell better than any other philosopher today (which is pretty ironic given his elitism). But in the end he is diagnosing an incoherence in Enlightenment ethics, taking them to their logical conclusion. -

A Reversion to Aristotle

A quick comparison of what clothing is acceptable today and 70 years ago, what sort of lyrics features in mainstream music, and all else shows otherwise. I wasn't around in the 60s, but I don't think children were being exposed to sexual content as extremely often as they are today.

At least in terms of the US I know that the Baby Boomers, on average, lost their virginity earlier than any other generation before or since, had more partners than any other generation, and used drugs more than any other generation. And of course the surge in crime rates starts as they come of age and peaks and then goes into rapid decline as they enter middle age. If anything, the opposite problem exists now. Young people are completely cut off from romantic relationships in many instances.

So, even if the content is a problem, and I'd still argue it is, it certainly isn't the case that it has outweighed other forces in the culture. You might easily argue that digital entertainment has simply become a substitute good for romance, sex, and drugs, and being more affordable you don't need to commit crimes to get all you can consume.

Actually, I'd argue precisely this. A straightforward analysis of "vice indexes" papers over the dire problems. Some young man wasting his life away in isolation playing video games is perhaps in many ways worse off than one who is promiscuous and involved in petty crimes.

That is hardly believable.

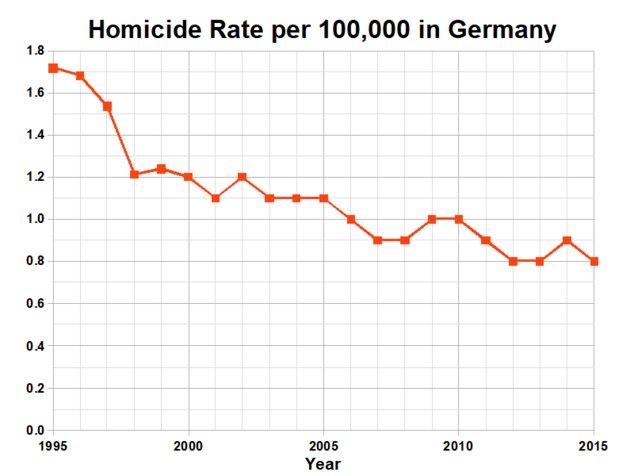

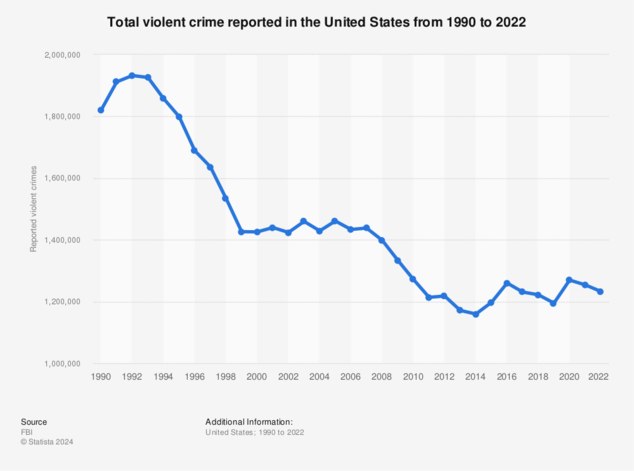

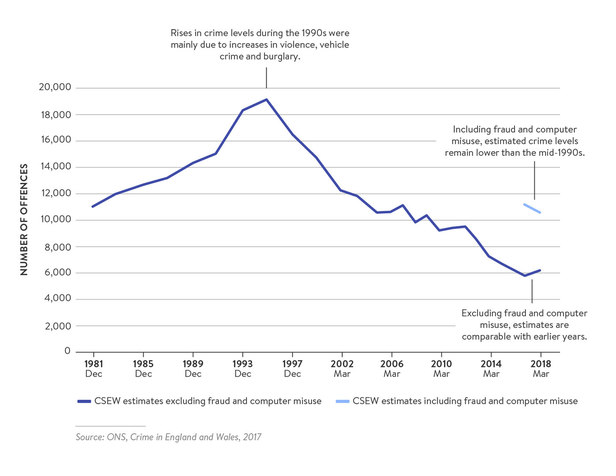

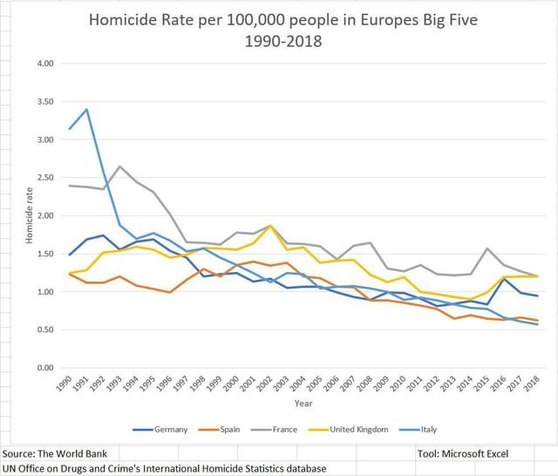

Is it? I suppose it depends on what your comparison was. I was thinking over the long term. Attempts to reconstruct the homicide rate of medieval Oxford for instance land well above modern Baltimore today. People seem to always think crime is getting worse, regardless of what actually happens with crime though.

Certainly descriptions of Victorian London are dire enough, hell scapes populated by almost entirely by depraved criminals, no-go zones for the police, etc. It even becomes hard to determine who Jack the Ripper's "canonical victims" are because so many dismembered women are being found around the same area in a short span.

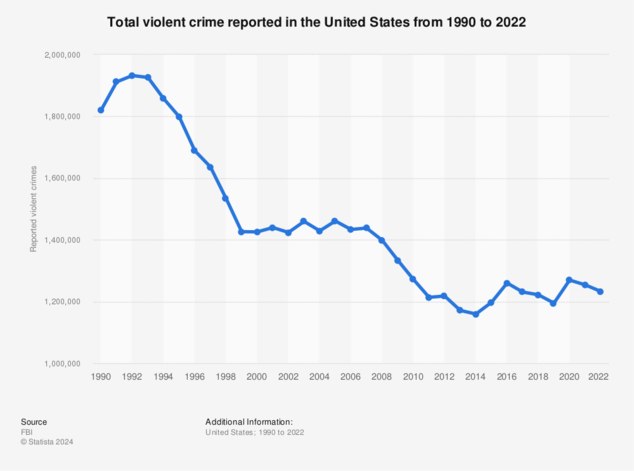

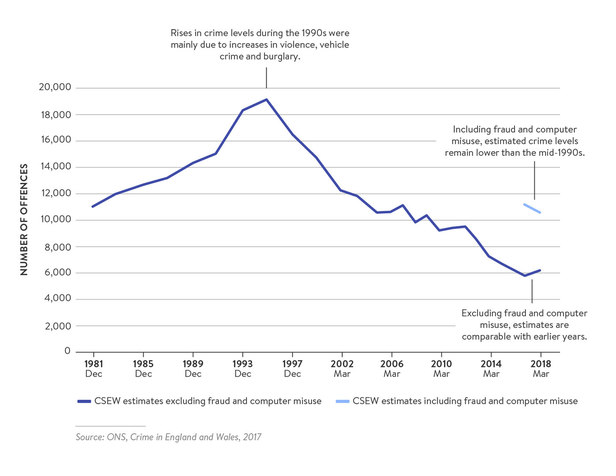

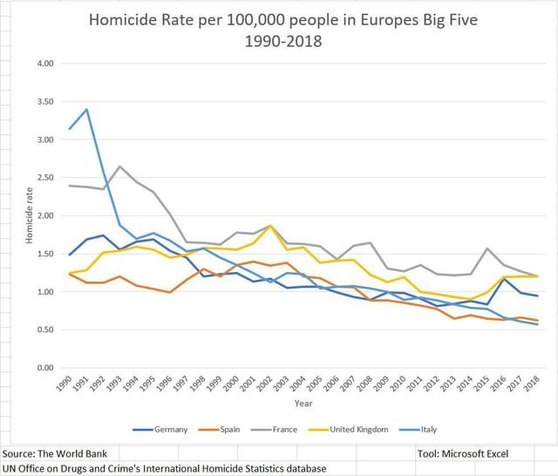

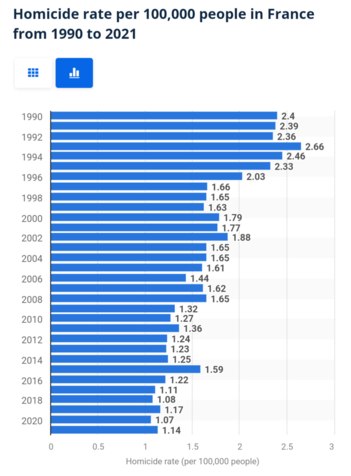

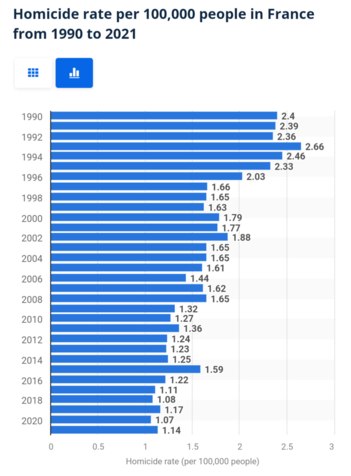

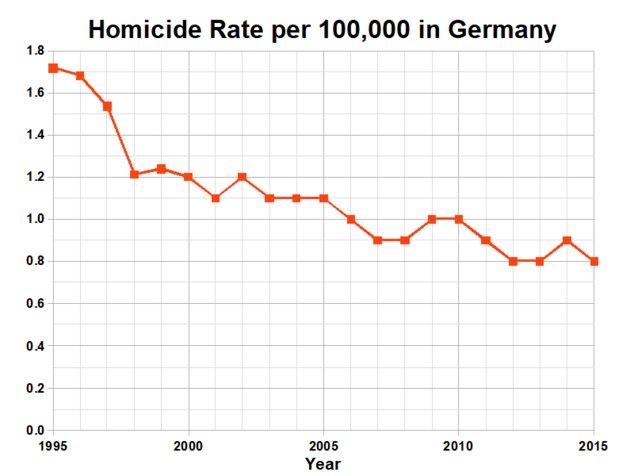

But as for recent history for the most serious crimes, there is a tend downward, although it's most pronounced in the US.

-

A Reversion to Aristotle

Well this is the big counterpoint to any thesis about modern "moral decay," e.g. MacIntyre's After Virtue. Violent crime is way down in Europe and the US. Wars kill a vastly smaller share of the population than in prior eras. New technologies have offered us all sorts of new opportunities. We each can carry the world's libraries around with us in our pockets, and even have texts read to us at will.

However, I do think this has to be weighed against other factors like the surge in suicides and "deaths of despair," as well as plummeting self-reported well being. Then there is declining membership in pretty much all sorts of social institutions, marriage, etc. Hell, even the age old past time of having sex or being in romantic relationships is plummeting, especially for the young. And then you have the political climate, which at least here in the US is arguably as bad as it has been since the Depression, even if it hasn't been particularly violent (yet...).

Plus, you have the long term moral import of climate change, ocean acidification, etc. hanging over us.

I am less sanguine about "every generation says the world is going to hell." There might very well be some truth to that, but we can look at history and see pretty clearly that sometimes it has gone to hell more in some periods than others. And in each of those occasions, be it the European Wars of Religion or the World Wars, there were warning signs in the sorts of ideologies and world views dominant prior to the cataclysms. Likewise, some of the better times in human history seem to have been supported at least to some degree by the thought of the time, although the influence is obviously always bidirectional here.

My view would tend towards the idea that ethics only has a major affect on the culture writ large when it is instantiated in cultural institutions and public policy (borrowing from Hegel here). Ethics can seem unimportant because it's often only seen as "ethics," when it comes down to the individual level, but policy is ultimately downstream of policymakers ethics. -

A Reversion to AristotleIt seems to me that the is-ought gap comes from the modern move to try to collapse practical (and aesthetic) reason into theoretical reason. Arguably, the disconnect is upstream of ethics, in metaphysics. Modern philosophy tends to assume that Goodness and Beauty are not properties of being, while Truth is generally kept in some form (although this gets the axe sometimes too).

The is-ought gap comes from asking theoretical reason to do practical reason's job. It's a category error from the older perspective; practical reason, whose target is the Good is what motivates us to act. This doesn't work for the modern perspective, which is fundamentaly uncomfortable with conciousness and tries to sequester it. This is because it isn't reducible to mechanism and because this would seem to keep the human sphere "free" as everything else is reduced to mechanism.

This is why so often today you see people trying to define the Good in terms of what people prefer/enjoy. The classical way to look at things would be to say: "people want what is good. When someone does x, they are seeking some good (even if it is a relative or counterfeit good)." Nowadays, you get something like "x is good because people are seeking it."

Why the inversion? It's the elimination or demotion of practical reason. Why people act has to be explained in terms of truth, either the theories of the social sciences or, as often, a mechanistic account based on the natural sciences is desired. Goodness still finds its way in, e.g. the black box of "utility" in economics, but its subservient to theory.

I've never come across the third objection. It seems quite at odds with Aristotle's philosophy. It makes it sound like Aristotle is talking about some "rational agent's" incentives to do whatever maximizes his or her "utility," not unlike Hume. If this were true, the same criticism MacIntyre levels against Hume would hold: "we should be good, pro-social, etc. just in those cases where it benefits us." But for Aristotle happiness always includes other people. Man is the "political animal." Happiness is a life in accordance with the virtues, which in turn precludes narcissism or selfishness.

In the Ethics he talks about the three levels of friendship. It is the first that is narcissistic—being friends with someone for what they can give you. The second stage involves mutual pleasure. The third is enjoying someone due to the good we see in them—enjoying that good for its own sake (there is a clear similarity here with Plato's description of love as "giving birth in beauty" within another). And this sort of non-self interested friendship is key to a good life. "Without a friend no one would want to live, even if possessing all good."

For Aristotle the human good is inextricably bound up in the polis as well.

The most choiceworthy life, on Aristotle’s view, is a pattern of activity that fully engages and expresses the rational parts of human nature. This pattern of activity is a pattern of joint activity because, like a play, it has various interdependent parts that can only be realized by the members of a group together. The pattern is centered on an array of leisured activities that are valuable in themselves, including philosophy, mathematics, art and music. But the pattern also includes the activity of coordinating the social effort to engage in leisured activities (i.e., statesmanship) and various supporting activities, such as the education of citizens and the management of resources.

On Aristotle’s view, a properly ordered society will have an array of material, cultural and institutional facilities that answer to the common interest of citizens in living the most choiceworthy life. These facilities form an environment in which citizens can engage in leisured activities and in which they can perform the various coordinating and supporting activities. Some facilities that figure into Aristotle’s account include: common mess halls and communal meals, which provide occasions for leisured activities (Pol. 1330a1–10; 1331a19–25); a communal system of education (Pol. 1337a20–30); common land (Pol. 1330a9–14); commonly owned slaves to work the land (Pol. 1330a30–3); a shared set of political offices (Pol. 1276a40–3; 1321b12–a10) and administrative buildings (Pol. 1331b5–11); shared weapons and fortifications (Pol. 1328b6–11; 1331a9–18); and an official system priests, temples and public sacrifices (Pol. 1322b17–28).

Aristotle’s account may seem distant from modern sensibilities, but a good analogy for what he has in mind is the form of community that we associate today with certain universities. Think of a college like Princeton or Harvard. Members of the university community are bound together in a social relationship marked by a certain form of mutual concern: members care that they and their fellow members live well, where living well is understood in terms of taking part in a flourishing university life. This way of life is organized around intellectual, cultural and athletic activities, such as physics, art history, lacrosse, and so on. Members work together to maintain an array of facilities that serve their common interest in taking part in this joint activity (e.g., libraries, computer labs, dorm rooms, football fields, etc.). And we can think of public life in the university community in terms of a form of shared practical reasoning that most members engage in, which focuses on maintaining common facilities for the sake of their common interest.[14] -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

Yes, but the explanation is partly "why do some things experience and not others?" So is the dual aspect supposed to hold for everything? For instance, there would be some sort of phenomena awareness for orange juice in a blender, a corpse, or water in a river?

If everything has this dual aspect, then there is still a question of why certain interactions give rise to certain experiences. There would be the question of why we have a phenomenal horizon at all, since everything experiences and there is constant interaction and a constant exchange of information, matter, energy, and causation across any boundary drawn up to demarcate a person. Presumably anesthetic would work by splitting the unified mind into a jumble of isolated minds? It doesn't seem like it can be turning off the universal dual aspect.

Whereas if everything doesn't have experiences then the gap is still there — there is still the question: why does the living body have this dual aspect but not the corpse? -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

If I have not made the difficulties clear, I fortuitously has an article in my feed that brings up most of the same problems:

Something seems wrong here: pain-pleasure inverts [people who's experience of pain is like pleasure, i.e. inverted qualia] seem nonsensical. But if we accept Chalmers’ conceptual distinction between behavioral functioning and subjective experience, then pain-pleasure inverts ought to be just as conceivable as regular zombies. The only way to reject the coherence of pain-pleasure inverts is to reject the initial division between the “easy” problems of behavior and the “hard” problems of conscious experience.

I argue a lot about philosophy on social media, and I’ve found many people thinking evolution would explain why we’re not pain-pleasure inverts. But if you think about it carefully, that doesn’t make sense. Natural selection is only going to be motivated to make me feel pain when my body is damaged if that feeling is going to lead me to avoid getting my body damaged. If we lived in the bizarre universe of pain-pleasure inverts, where pleasure generally leads to avoidance behavior and pain to attraction behavior, then we would have evolved to feel pleasure when our body is damaged and pain when we eat and drink. Pain-pleasure inverts that eat and reproduce would pass on their genes just as well as us. In other words, evolutionary explanations of our consciousness presuppose that we’re not pain-pleasure inverts, just as they presuppose the existence of self-replicating life. In either case, evolution cannot explain what it already assumes...

This has become known as the mystery of psychophysical harmony.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-mystery-of-consciousness-is-deeper-than-we-thought/

Except this article misses the epistemological challenges that follow on from lacking an explanation of psychophysical harmony since there is now also no good reason to think experience has to have anything to do with the mechanism underlying it. Evolutionary psychology generally simply assumes that qualia intersect with intentionality to play a causal role in behavior, which seems like a fine assumption since it seems to be constantly verified by experience, but it doesn't explain how this interaction occurs. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

Again, this is simply because you have fallen into the Cartesian representationalist trap of reifying phenomenal experience as a mysterious substance.

I don't think I have. I start to feel like a broken record here with how often I advocate for a metaphysics or phenomenology of process. I have long been a critic of representationalism and indirect realism, and an advocate of the semiotic model as a superior conceptual alternative. Descartes didn't invent the idea that we have experiences, this is a basic fact of life explored throughout the history of philosophy. "Why do some things have experiences and others do not appear to?" is not a question that only shows up if you suppose substance dualism. Even idealists of the sort that posit that everything is some sort of "process of mentation" feel the need to offer up some sort of explanation of why presumably stars are not conscious and people are (or else to claim stars are concious in a univocal way).

You can't get away from the primacy of the looks and feels. They have become what "must be explained".

Yes. Since this is generally proffered up as "the biggest open questions in human inquiry," I don't think I'm alone here.

What we as the only biology, and even neurobiology, to be enhanced with the further levels of semiotic technology in our language and logic systems, might "feel" as organisms engaged in just that kind of reality-modelling relation.

Once you add enough social psychology, psychophysics, neurocognition and other good stuff to your understanding, it is easy to see why being on a modelling relation with a world would have to feel like something. How could it not feel like something to be a self engaged in a world in this feedback loop way?

I am not seeing how this is "closing the explanatory gap." This is presenting a certain sort of view of biology and physics, one I largely tend to agree with, at least in that is seems to get some things right, and then turning around to say "how could this not produce the experiences of a human?" IDK, I think most people studying conciousness would allow your core premises, but the idea that inner life of just the sort we have must follow from these premises doesn't seem to follow. At the very least the demonstration is extremely obscured because I can't even tell why you seem to think the premises imply your conclusion. For instance, saying that we can distinguish between which complex systems are concious based on their possession of an "umwelt" and "self-interested" pursuit of goals just seems to point to terms that assume the very thing in question. It's like saying a drug "makes one sleepy because it possessed a hypnotic property."

What underlies conciousness just happens to line up with our naive intuitions about what sorts of things must have some sort of "inner life," because... "how couldn't it?." IMHO, this is a non-explanation, a hand wave on par with eliminative materialism or appeals to an unexplained "strong emergence." I don't see how this explanation avoids the problems of having group minds everywhere either, which is an ancillary concern, but still an important one.

I'm still not really sure what you're proposing. It seems like some sort of dual aspect theory where certain sorts of mechanism just "have to" produce certain sorts of experiences. But I've already pointed out why I think such explanations have some serious epistemic and evidentiary hurdles to clear, and I don't see how they are addressed here.

For what it's worth, the presentation seems to me a lot like most eliminitivism. You're presenting all sorts of facts and models, ones I largely find interesting and convincing, "good ways to think about things," and claiming all of this is evidence for your position vis-á-vis the explanatory gap. I don't see how it is, the idea that our experiences are just "how certain sorts of systems have to feel" just seems like assuming the conclusion as self-evident. If you want to to convince people (and maybe you don't, but surely most people don't think the explanatory gap has been solved) it might be helpful to lay out the core premises and how the conclusion is supposed to follow from them. -

Currently ReadingThat All Shall Be Saved by David Bentley Hart. It's a book on Christian universalism, although it is more focused on rebutting infernalism (belief in eternal, punitive Hell as opposed to remedial Hell). Sandwiched in here are some of the most cogent (if not necessarily accessible) explanations of the classical view of freedom and the Good as a transcedental property of being. It's written quite well, although probably too combativly to serve its purpose.

Aside from the philosophical arguments it covers the paucity of scriptural evidence for infernalism, amounting to just Matthew 25:46 and some heavily symbolic language in Revelation. This is set against the fact that language suggestive of universal redemption: "all," "the entire cosmos," "every" etc. shows up in all four Gospels, most of the Epistles, and Revaluation, often in very explicit terms. There is also a good deal of annhilationist language (although significantly less than universalist).

In general, the arguments are made very well. The only one that seems weak is the claim that the blessed in heaven would have to be so radically changed not to mind that their loved ones were in Hell as to have become completely new people (and thus it really wouldn't be "them" getting beatified). This is a fine point to make, but it cuts both ways. A true monster like the BTK killer would have to be so radically changed to be saintly as to also have been entirely stripped of their personality. Perhaps this could be proffered as the explanation of the annhilationist language though—there is plenty to suggest that salvation is not a binary.

Finally, he covers how infernalism was virtually absent from the early church and failed to take root in precisely the places where the texts could be read in their native language.

I was impressed by the prose and reasoning so I got his "You Are Gods: On Nature and Supernature." This one is much more scholarly and is dealing more with highly philosophical issues. It includes a really good paper on Nicolas of Cusa, and another on classical aesthetics. I am not super familiar with Orthodox philosophy (he is Orthodox) at any advanced level, but a lot of what he lays out is quite consistent with the Catholic tradition. -

My understanding of morals

My answer has been that you cannot generally justify a positive ethic over a negative ethic if there was no need for it.. In other words, if I am causing the source of harm for you (negative ethic), in order to make you go through a positive ethic (character building) this is wrong. However, if you are ALREADY in a situation whereby you need remediation (child-rearing), it may be said that if one is the caregiver, one can impose a positive ethic, as it is now perhaps necessary in order for the person to flourish in the future in some way. The harm has been done (one failed to prevent), so now one remediates.

How does this work with billionaires sitting on their fortunes like Smaug and trying to tax them so you can provide for the common good? You're clearly causing at least some of them great harm, to hear them talk of it anyhow, and they are only going to benefit from the harmful tax in a rather indirect way.

Or military conscription? Harming older people through climate change legislation that will have no meaningful impact in their lifetimes?

Common good and collective action issues seem to be an issue.

As far as anti-natalism (I did start Ligotti's book, it's quite good), the principle of "you should never deprive someone of happiness or pleasure for no reason" would just cut the other way, no?

My first thought is that you could probably cleverly rework most positive statements into negative ones or vice versa. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

Yes, I see.

As with a tornado, half the job of being alive and mindful is done. Then life and mind become a simple, mechanical, addition to the organic flows - semiotic codes colonising the great entropy gradients like the original "earth battery" of plate tectonics that drove the sea vent origins of life, and the daily solar flux that eventually put life on a much more generic photosynthetic footing

And as you can see, I wasn't at all hostile to the approach, but I still don't think it answers a single one of the points I brought up.

It also seems like that view is going to run into another problem. Lots of systems function like organisms: ant hives, ecosystems, cities, corporations. They are all shaped by selection forces and are explicable in terms of entropy gradients, and can certainly be described as self -organizing structures. "The Ascent of Information," is a neat, light popsci book on just this sort of take. But then it seems we should actually have tons of minds nested within each other. This is a problem for many formulations of IIT too, you get group minds everywhere, which seems to strain credulity. If Toyota, the City of Miami, and memes are all "concious" they seems to be so in at best an analogous way.

But against this, we might consider global workspace models of conciousness and the decent empirical support that suggests they get something right, which would seem to suggest that something much more definiteness is required to result in phenomenal awareness than having a metabolism, etc.

The solution is even older, it gets posed by Plato in the Phaedo and is there ascribed to the Pythagoreans. The material metaphysics is familiar, since it really hasn't changed much. For the Pythagoreans life was a process. It was said to be analogous to a harmony (tuning) on a lyre. The strings are what we observe around us, matter, the harmony, is us experiencing things. The harmony just is the vibration of the strings (ignoring the air for now).

But as Plato points out, this implies something like causal closure. If intentionality just is mechanism "seen from the inside" it can never have any sort of causal relationship with mechanism, they are the same thing. Their relation is identity.For Plato, this is a reductio because, clearly, we sometimes do things because we choose to do them, because we find them pleasant, etc.

So I think the same issues show up there. If our experiences were just mechanism as seen on the inside then there is no reason for the content of those experiences has to have anything to do with the underlying mechanism. You need some sort of explanation why mechanism must produce experienced that are "like" the mechanism that causes them. This seems hard to do if they just are the same thing, but maybe it's possible. Such an explanation doesn't exist though. That, and there seems to be a lot of good empirical support that experience "feels the way it does," in order to motivate us to do things, including misrepresenting reality for selection advantage.

I consider this a difficulty for panpsychism as well. Even if we assume panpsychism, why do we assume that it has to result in experiences that relate closely enough to the underlying/flip side mechanism for us to trust our observation?. There is no prima facie reason they seem to need to. And then there is the issue I pointed to before which is that the psych part of panpsychism is seemingly unobservable "from the outside" and so not only unfalsifiable but also seemingly unconfirmable except maybe by process of elimination of plausible alternatives. This isn't true for all panpsychism, really just those ones that say there isn't anything more to explain because experience is just one side of the dual aspect of one thing, but that's the most common sort. -

"Aristotle and Other Platonists:" A Review of the work of Lloyd GersonAnyhow, to circle back, when it comes to skeptical or ironic interpretations of Plato, I think one problem is the work of Aristotle. Here, you have a guy equipped with a brilliant mind who studied with the man for years who seemed to miss the memo. He seems to think he has solid metaphysical theories to enhance or rebut.

The skeptical Plato at least has some things to recommend it. However, I find it very hard to even see the bare bones of Fooloso4's reading of Aristotle where he, in what are essentially lecture notes, is trying to engage in dialectical and lead us to aporia ("the attentive reader is not led to conclusions but to questions and problems without answers"). I think the thread trying to read the Metaphysics this way sort of speaks for itself, it ends up saying nothing of what it straightforwardly says when taken this way. I've never come across a "skeptical Aristotle," in my reading, and I think there is a good reason for that. The Posterior Analytics in particular, with its ideal of sciences flowing neatly from self-evident axioms in logical demonstrations is sort of the opposite. I don't think a skeptical Aristotle is any more plausible than a skeptical Kant who brings up the antinomes just to get us questioning and then purposes the transcedental deduction as a hypothetical for moral edification.

The thesis that Aristotle was a Platonist (e.g. Perl) rings true with me. The thesis that Aristotle was a skeptical Platonist seems particularly far-fetched, the author of the Posterior Analytics was not a "zetetic skeptic."

Yet, in any case, one thing Plato would almost certainly agree with is that his opinion doesn't ultimately matter that much. There is always the possibility that what Plato intended was still wrong, be it "Platonism" or something more skeptically oriented.

That's a fine interpretation that adds an additional dimension. The interlude also seems to mean what it straightforwardly says, which is "if you find out an argument you thought was good is bad, don't distrust reason and argument as a whole," which is sort of the opposite of zetetic skepticism. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

Translating the metaphysics into the language of a science may make it accessible to a larger percentage of the population , and therefore more ‘universally relevant’, but by that same criterion the translation of a basic science into technological devices is more relevant that the basic science by itself. In any case, naturalizing and empiricizing it doesn’t make it more “intersubjectively valid” , it just makes the terms of its philosophical validity intelligible to a larger community.

Sort of unrelated, but maybe there is a case for technology "objectifying natural philosophy," in the same way Hegel supposes that institutions "objectify morality." It's the concretization of theory in history.

Obviously, this is a somewhat particular use of "objectifying," in which to "objectify" is partially to "make the terms of philosophical validity intelligible to a larger community." Such an objectification doesn't preclude later negation. New technologies bring about new contradictions and often eventually get replaced or modified beyond recognition.

Just a thought I had, really not applicable to the topic I don't think. -

"Aristotle and Other Platonists:" A Review of the work of Lloyd Gerson

I think you're absolutely right about the significance of the myths existing as such, and the import of the warnings against accepting them dogmatically. I suppose we disagree about their exact function though.

I sometimes wonder what Plato would have thought about analytic philosophy with its extreme focus of formalism and decidability. In some ways, Plato seems like the progenitor of the preference for the a priori, and in others his ecstatic view of reason seems completely at odds with it.

As you say, Plato's goal in motivating questioning is definetly there, but I also think this is instructive in more than one way. It points to how reason goes beyond itself, its lack of limits (which in turn points to its ability to radically undermine itself).

IMO, the lessons one learns in Plato do point towards a type of skepticism. This would include skepticism vis-á-vis those sorts of systems that elevate a sort of doctrinal formalism (what can be said). But my take would be that the bigger lesson is not so much that we should be skeptical of such things, but that they aren't truly valuable. That is, even if we could erase our concerns and overcome our skepticism vis-á-vis such presentations of truth, we shouldn't want to, because the truth we'd be sure of would be an impoverished form. And this is why Plato keeps prodding us to never settle down with what is in the text itself—the ideal orientation is towards the Good and True, not towards any specific teaching (edit: ...that can be formalized. That's the point of all the images and "myths." But I would disagree that they are offered up pragmatically or hypothetically). -

"Aristotle and Other Platonists:" A Review of the work of Lloyd GersonOne of my favorite explanations of Socrates' reticence to speak or to claim special knowledge for himself, particularly in the Republic.

From D.C. Schindler's "Plato's Critique of Impure Reason."

Moreover, we recall that Adeimantus had added a challenge to his brother’s. The whole of ancient literature, poetry and prose, he claims, “beginning with the heroes at the beginning (those who left speeches) up to the human beings at present” (366e), has justified justice only in terms of its good con-sequences. As we proposed in the previous chapter, the fact to which Adeimantus points is not true simply de facto but also de jure: it is precisely the relative goodness of a thing that can be defined and described with mere words. An argument for the intrinsic goodness of something must necessarily be more than a mere argument: it must be an argument that springs from the wholeness of a life. The wording of Adeimantus’s challenge is crucial, insofar as it associates discourse with relative goodness and insists on more immediate evidence for intrinsic goodness: “Now, don’t only show us by argument (τῷ λόγω) but show what each in itself does to the man who has it” (367b). We have here an allusion to the more intimate form of knowledge we have argued lies at the heart of the epistemology of the Republic and distinguishes it from Plato’s other dialogues. There is no better way to show the effect of something that inheres in the soul than to live out its effect; indeed, anything else can be feigned. It is in this sense that Plato points to philosophy as supplanting poetry as the foundation of social order: not in the first place because he takes philosophy to be a superior mode of discourse (an affirmation that will need to be significantly qualified, as we shall see in the coda), but because philosophy is in fact a life if it is philosophy at all, while poetry need never be more than word.

Or as Eva Brann puts it in The Music of the Republic: at the center of the Republic there is more than a logon, there is an ergon, a deed. Each of the main images Plato uses (the sun, the divided line, and the cave) are incomplete. Something must "come from outside" to relate to the whole. For instance, the Good can't lie on the divided line, since this would just make it one point among many. With the cave, it is Socrates who breaks into his own narrative, we are directed to the historical person of Socrates who demonstrates his knowledge of the good, not through speeches (which always deal with inadequate good) but through how he lives his life.

It's also worth noting that the imagery in the Protagoras seems designed to recall Book XI of the Odyssey. Decending into the realm of relativists who make arguments purely for relative advantage and relative goods Plato frames as "Socrates' descent into Hell."

Continuing...

We receive more light on the exchange when we see it not simply as an interaction between two different moral characters but more fundamentally two different ways of knowing, different understandings of understanding, different views of what is most real. Socrates’ reticence, and Thrasymachus’s incapacity for it, are functions, we suggest, of two different ways of relating to ideas. Socrates professes no knowledge, and yet he remains throughout the dialogue a sort of anchor around which the discussion is ordered. Thrasymachus professes knowledge, and yet never seems to stick to a basic stance.

How are we to make sense of this paradox?

We are not yet in a position to deal with this question adequately, but we can make a certain straightforward observation. While Socrates denies definitive possession of knowledge, here he suggests he has a certain idea, which Thrasymachus’s strictures prevent him from proposing (376d). In other words, he does not yet reject the possibility of understanding a priori—for that would, indeed, depend on an insight it would be presumptuous to claim—but suggests that the activity of proposing and considering an idea does not depend on him alone. Instead, it requires the willing participation of others. For Socrates, an idea is essentially something that must be “inquired into.” For Thrasymachus, by contrast, an idea is not something one explores, reflects on, penetrates, or tests, it is something one simply asserts and, if necessary, defends by further assertions.

Schindler will later argue that Socrates' reticence is a lure, both to get the reader to engage and, reflecting this in the text, to pull Glaucon in with him. But reticence and openness is also a sign of a certain sort of relationship with the Good:

Plato suggests that the communication of knowledge requires, so to speak, a community in goodness between teacher and student. This entails a willingness to be tested through questioning, a willingness to respond, and in general, good will and lack of envy.56 It is interesting to note that all of these characteristics point to the affirmation of a good beyond oneself, by which one is measured and to which one is responsible. If it is the case, as we have been suggesting, that an indispensable aspect of knowledge is the mode of relating to reality by which the soul subordinates itself to goodness, then it follows that substantial thinking and genuine communication cannot take place outside of the spirit created by a basic disposition toward goodness. The good, then, is the single condition of possibility of communication, insofar as it gives being to what is talked about and imposes certain demands, intrinsic to that being, on those who wish to know and thus to speak properly. In this respect, to teach in the fullest sense means to impart not just ideas but a relation to the good, and one can do so, and foster such a relation, only if one is in love with the good, as it were.57 To communicate truth requires a love of beauty and goodness. Be good, then, and teach naturally.

But another key thing here is that all of the characters Socrates speaks to seem to embody one of his "types of men" (e.g. timocratic, oligarchic, tyrannical, etc.). By the end of the dialogue each moves up one spot on the hierarchy. Thus the imparting of knowledge of that cannot be spoken of in mere words, but which must be lived, is imaged in a story where the fruits of knowledge show up in the deeds of those involved. -

It's Big Business as Usual

When will it all be enough money for his mentor?

Reminds me of all of Kierkegaard's language re subjectivities attraction to the infinite (good). There is something to the idea that desires never come to rest in the merely finite (Kierkegaard, Nicholas of Cusa speaks a lot about this too). -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)But inside the White House, Biden’s growing limitations were becoming apparent long before his meltdown in last week’s debate, with the senior team’s management of the president growing more strictly controlled as his term has gone on. During meetings with aides who are putting together formal briefings they’ll deliver to Biden, some senior officials have at times gone to great lengths to curate the information being presented in an effort to avoid provoking a negative reaction.

“It’s like, ‘You can’t include that, that will set him off,’ or ‘Put that in, he likes that,’” said one senior administration official. “It’s a Rorschach test, not a briefing. Because he is not a pleasant person to be around when he’s being briefed. It’s very difficult, and people are scared shitless of him.”

The official said, “He doesn’t take advice from anyone other than those few top aides, and it becomes a perfect storm because he just gets more and more isolated from their efforts to control it.”

https://www.politico.com/news/2024/07/02/biden-campaign-debate-inner-circle-00166160

Sounds like the sort of dynamic that often leads to autocracies' great blunders. Perhaps it's not as extreme as the "yes-man" problem described vis-á-vis Putin's inner circle, but there seems to be an apt analogy in Biden's decision to run for a second term being his "let's go invade Ukraine," moment. Now there is nothing left but to keep doubling down and everyone with any influence to stop it doesn't want to risk losing their influence by actually trying to stop it.

There was a similar dynamic reported in Trump's cabinet, but there at least many cabinet members did eventually jump ship and begin publicly blasting their old boss (fat lot of good it did lol). But obviously the provocations there were even greater. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

Talk of "phenomenal experiences" is just the standard sin of reifying a process as a substance. Tell me what process you might have in mind here and we will get a lot further. Consciousness is a pragmatic modelling relation with the world and not a "thing" or a "state of being".

I'm 100% willing to grant that experience and thought are processual. I don't see how the really changes anything though. I am referring to the process by which we have phenomenal experiences, "taste an apple," "think about work," or "feel pain," nothing more or less.

Such confusion. Talk of "phenomenal experiences" is just the standard sin of reifying a process as a substance. Tell me what process you might have in mind here and we will get a lot further. Consciousness is a pragmatic modelling relation with the world and not a "thing" or a "state of being"...

Yours is the argument that self-refutes. The semiotic approach indeed explains how our phenomenology indeed does "drift arbitrarily far from whatever the world is actually like"...

All the worthwhile theories of mind are based now on this semiotic principle. Perception itself is an encoding of telic purpose. What matters in an evolved information processing sense is built into the structure of our sensations let alone our cognition.

You are not describing a process where conciousness "drifts arbitrarily far" from the world. You are describing a process where its contents are based on what is useful for survival. This isn't "arbitrary" or "random." Things are presented based on their relevance to fitness in your description and presumably natural selection is selecting for "what experience feels like," here.

But then you didn't answer my question: does subjective experience ever play a causal role in behavior? Does the way we feel about things dictate how we act, or are organisms' actions entirely explicable in terms of more basic physics?

Strong emergence is just reductionism plus supervenience. A complete non-theory. A way of hand-waving rather than actually explaining.

I'm not sure what to make of the first sentence. "Strong emergence," is defined in terms of superveniance and is the explicit denial of reductionism. I do agree that it's a way of hand waving though. It's a very popular way of hand waving because of seemingly intractable problems with physicalism defined under causal closure.

I bring it up because phenomenal awareness being explicable in terms of statistical mechanics would seem to suggest causal closure because statistical mechanics is, as the name implies, mechanistic. If it doesn't, how is this avoided?

Friston's Bayesian Brain seems to have taken the field by storm. We were discussing it 30 years ago when it was still rather radical and leftfield. Now he has the field's highest impact rating – even if a lot of that is due to his work sorting out the analysis techniques needed for functional brain imaging.

There is probably a consensus that it gets "something" right. It certainly isn't the case that it is taken by more than a few to present a "fully adequate" explanation of how first person experience emerges, and it has plenty of critics. Indeed, the field seems dramatically less unified than it was two decades ago, which is not the sign of a mature field. You get conferences where like six different, mutually exclusive "ground up" theories of conciousness get presented.

Likewise, the stuff about the universe being cyclical, while certainly interesting, is extremely speculative. Forgive me if I'm skeptical of a skeleton key that seems to open many of the biggest open questions in the sciences. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

I did say I didn't understand what he was talking about. I still don't lol, this may be on me. I was throwing out what I see as wrong in most theories of reductive/substance physicalism, to see how he could respond to them. I'm always interested in ways around these, having found few.

That's why I said, at the end "if on the other hand conciousness is irreducible to physics, how are these two "goodnesses" univocal?"

I don't see your reasoning here. If phenomenal experiences "drifted arbitrarily far from whatever the world is actually like" then we could not survive. It seems obvious that the contents of awareness do have bearings on reproduction and on behavior in general. Who are you arguing against here?

Under most definitions of causal closure, the phenomenal/mental never, ever, on pain of violation of the principle, has any causal effect on behavior. So if something never affects behavior, how can it possibly selected for?

Under reductionism, if physics is "mechanistic," then any and all phenomena can ultimately be explained in terms of mechanism.

Regardless of the relevance of this point in the current conversation, I think it is underappreciated in general. Physicalism is normally defined in terms of superveniance paired with causal closure. It's not defined in terms of casual closure arbitrarily though, plenty of work, Jaegwon Kim's in particular, seems to suggest that jettisoning causal closure means jettisoning a lot of the basic assumptions of substance metaphysics.

Of course, this is absolutely no problem for science because it will posit mental causes whenever it seems like a good explanation. This is, IMO, precisely the problem for reductive explanations—they must explain why something with no causal efficacy (the mental is just "along for the ride") seems so good at explaining things.

And that's where my post comes from. I see this problem as very dire and difficult, and so "does it fix this problem," is one of the problems I ask of theories of intentionality.

Of course, if a theory isn't reductive, it has to explain how it gets around being so, which also isn't at all easy. But I'm at least sympathetic to arguments that reductionism "must be wrong," even if we don't know exactly how. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

I may have been unclear here. The language of values makes sense for those who chose to use it: Weber, Nozik, Rawls, etc. I was thinking particularly of backwards projecting the term onto thinkers from centuries prior. It seems to lead to confusion both because of the other connotations of the word and the way it is commonly understood today (which has bled into everyday life, e.g. "family values," etc.).

The language of "inherit value," used today might actually be a decent enough expression for older aesthetic theories, since the experience of the beautiful is "valuable for itself," and makes no necessary moral claims on us, but it isn't great the moral language of prior eras precisely because they draw a contrast here between the Good and the Beautiful. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

But all this is perhaps "too new" for you to realise how old hat your views of thermodynamics is?

Color me skeptical, but this new view of thermodynamics has now settled:

-the origin of the universe,

-the ultimate fate of the universe,

-how mind emerges and why it has the contents it does,

-and gives us a theory of morality? -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

It happens sometimes. The cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman gets around to arguing for a sort of vaguely Hegelian objective idealism. The Fine Tuning Problem and some people's problems with multiverse has led to the Von Neumann-Wigner "Conciousness Causes Collapse" interpretation of quantum mechanics to get done fresh looks, and this is sometimes framed in such terms.

I'll admit that it does at least answer FTP. Why is the universe supportive of life? Because possibility retroactively crystalizes into actuality only when it would have spawned life. And why is it set up for complex life? Presumably because this does more to collapse potential into actuality. But honestly, this one always seemed a bit much for me because it seems unfalsifiable in a particularly extraordinary way. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

I can't really tell if it makes good metaphysical sense, that's why I asked all those questions. For example, if such a grounding of intentionality reduces to mechanism, i.e. something like causal closure (is it supposed to?), then I would say such a theory has dire epistemic and explanatory issues.

The thing is, if intentions have no causal efficacy, if everything is determined by mechanism—by statistical mechanics, etc.—then the contents of phenomenal experience can never, ever, be selected for by natural selection. This has two problems:

The first is epistemic. If how we experience the world and what we think of it has no causal effect on behavior, then there is no reason to think science is telling us anything about the way the actually world is. Natural selection would never ensure that phenomenal experiences don't drift arbitrarily far from whatever the world is actually like because the contents of awareness have absolutely no bearing on reproduction if they don't affect behavior. It's self refuting.

So folks who want to have people accept these sorts of narratives need some sort of "just so" story where "information processing," or some such, when it results in phenomenal awareness, just happens to not allow the contents of awareness to drift too far away from reality. But why should this be?

The second is explanatory. Evolution explains a lot of phenomenal awareness: why sex feels good, why sweets tastes good, why being tired feels such that you don't want to do anything. Yet if awareness doesn't dictate behavior, then sex could feel like torture and it would make no difference for reproduction. The "way things feel," could never be selected for (barring some "just so story" where somehow behavioral outputs drag along the contents of awareness with them).

Finally, there would be the fact that phenomenal awareness would now seem to be a sort of unique, sui generis sort of strong emergence, but not only that, it would be the only phenomena we have ever observed that only demonstrates causality in precisely one direction. Even with the introduction of panpsychism, this seems to remain a problem. I don't think it's unfair to say this one is only slightly less problematic than Cartesian dualism's interaction problem, it almost amounts to the same thing in many respects.

To my mind, those are big problems even for a theory that could lay out an adequate explanation of how first person experience emerges from entropy, information processing, computation, etc., which absolutely none can (and here most authors readily admit this—whoever figures this out will have a claim to surpassing Newton or Einstein). All we have is multiple competing "suggestive" theories, none of which can gain currency.

On the other hand, if a theory allows for something along the lines of "strong emergence," to get around these problems, I have no idea why we would be talking about mindless entropy gradients and intentionality as good in a remotely univocal or even analogous way. Goodness, as we experience it, would be defined in terms of an irreducible intentionality. This doesn't mean thermodynamics or complexity studies can't inform us about the nature of phenomenal awareness or how it emerges, but it would mean there is no reduction such that the goodness of practical reason can be explicable purely in terms statistical mechanics. -

Pragmatism Without GoodnessReturning to the original topic, I do wonder how much of the success of anti-realism has to do with how people have learned to think of alternatives to it as being something like positing "objective values." The focus on "values" doesn't really fit with philosophy prior to the 19th century. In it's current usage, it's a term coming down from economics. Nietzsche seems to have been big in popularizing it, and I honestly think he uses the shift to "values" as a way to beg the question a bit in the Genealogy (to the extent that it assumes that the meaning of "good" has to do with valuation as opposed to ends). I'd agree that the idea of something being "valuable in-itself," is a little strange, since "value" itself already implies something of the marketplace, of a relative transaction or exchange. At the very least, it seems to conflate esteem with goodness, which essentially begs the question on reducing goodness to subjective taste.

Presumably, Goodness, at least as the target of practical reasoning, has to have something to do with what people desire. However, to simply claim that Goodness is equivalent with whatever people happen to desire is to deny any reality/appearance distinction as respects the Good, which in turn entails that no one can ever be wrong about what is good for oneself. This is clearly false, which is why even Thracymachus rejects it out of hand when it is offered up to him as a way to defeat Socrates in the Republic. So it can't be a perfectly straightforward relationship. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

The whole idea of human flourishing is meaningless is it doesn't fulfill things people want or like. You cannot be "flourishing" and simultaneously not enjoying things in some sense or getting something you want out of it.

Yes, I agree 100%. And this sort of gets at why Hegel thinks he can focus on freedom instead of Aristotle's eudaimonia (flourishing). Freedom implies happiness. A person does not freely choose to be miserable. To be miserable implies that one is in some way unfree to actualize one's desires (even allowing that, in practice, one might choose some degree of misery to actualize some higher good—but no one chooses misery for itself.)

Even Milton's Satan has to say "Evil, be thou my Good," since to choose evil as evil (as evil vis-á-vis oneself) is incoherent.

But I don't think our options are "the Good and human happiness reduces to pleasure, even completely unfree, infantile, bovine pleasures," or else "flourishing must be divorced from pleasure." For one, a human good defined in terms of such pleasure makes a person entirely reliant on what is extrinsic to them. The Gammas of A Brave New World fall into enraged rioting when their Soma is denied to them, and they would suffer starvation if their keepers ever neglected them. Such pleasure is not only largely bereft of beauty (and so inferior), but it's also intrinsically unstable because it doesn't generate itself.

The inverse of this sort of entirely extrinsically dependant good would be Socrates proclaiming that "nothing bad can happen to a good man," even as he faces execution. Or perhaps St. Ignatius and Boethius' serene and, ultimately, happy outlook, even as they are deprived of all comforts and face ghastly deaths.

Clearly, the only way that a utopia can fail is that it has consequences which are things people do not actually want or like. The idea of "good" things is utterly meaningless unless people are receptive to those things because it benefits them, i.e. it gives them something they want or like in some sense.

I agree, but would add more to this. The Good is the ultimate object of desire. People always choose things for some good they see in them if they are making any rational choice at all. But there is a difference between "what people currently want," and "what people would want if they were continent and possessing of all relevant knowledge." Clearly, we can prefer things that we later realize were extremely bad for us. The Good is not best judged from "any current vantage," but clearly better judged from a place of knowledge than a place of ignorance.

Indeed, for Plato, Hegel, Augustine, and a good many others, it is precisely our ability to ask "but is this truly good?" that gives us any ability to be self-governing in the first place. It is the open-ended nature of practical/moral reasoning that allows us to transcend current desire and opinion, and so not to be completely determined by what we already are. To paraphrase Socrates in the Republic, people want what is actually good, not what merely seems to be good or is said to be good. It would make no sense to "choose the worse," in the very same way that, from the perspective of theoretical reason, it would make no sense to embrace falsity over truth vis-á-vis what ones thinks is the case.

So good/bad can be grounded in this larger thermodynamic view. That was my point.

To be honest, I read your post a few times since I am a fan of CSP (as well as Deacon and other's attempts to use thermodynamics to explain intentionality), but it seems to me like you simply assume this and go from there. Perhaps I am missing some key bridge here?

In what sense can anything be "good" "from the perspective of the Cosmos?" Is the Cosmos self-aware? Does it have intentional, goal directed thoughts and experiences? Intentionality?

"But the Cosmos lacks this level of organismic purpose. It just is what it is," would suggest not. So what is the meaning of this "good" that has been voided of all intentionality and cognitive content? What does it mean that "goodness" is defined in terms of such a good? Something along the lines of eliminative materialism would be my first guess, since this global "good" would be bereft of any cognitive content and is simply defined in terms of a statistical fact.

And how can the Cosmos be self-organizing while lacking any self? Wouldn't the words "spontaneously organizing," or "mechanistically organizing by the laws of chance," describe essentially the same phenomena without the equivocal use of "self" to describe a statistically driven mechanical process?

There seems to be a large distinction between "the reasonable universe," which seems to actually be acting "for no reason at all" and the "reasonable creatures," who act for intentional purposes. The use of "good" for both seems completely equivocal. And perhaps this is why you have put "good" in quotes when referring to the universe?

But then, to my mind, it is only the creaturely "good"—the only one that actually involves a "self" or any cognitive content, intentionality, and goals—that bears any meaningful resemblance to "goodness" vis-á-vis mortality. So we seem to be back to where we started, since I don't think very many would deny that the "human good" or "happiness" is conditioned by (if not reducible to) biology, or that such goodness has to do the goals and intentions of minds.

For the first "good" to be good, we'd have to say something like "the universe is happy when it increases entropy at a greater rate." I don't know why we'd think this though, and at any rate, this would seem to assume that the final resting happiness for the universe is not "self-organization" but the annihilation of heat death. This gets at why Aristotle feels he needs a mover behind the world in order to anchor its final cause.

As to the reference to goodness as "mathematically grounded," while I very much appreciate Deacon's work and similar projects by others to ground intentionality in thermodynamics, these absolutely do not in any way give an adequate explanation for how first person subjective experience and purpose emerge. They might "get something right," but it's a very incomplete story. However, the most compelling parts of these sorts of explanations are, IMO, grounded in accepting a process metaphysics that removes the need for "strong emergence" even as it allows for something that is similar in key ways. But such explanations inherently deny reductions. Hence, while consciousness might be describable in terms of mathematics, it would not be what it is in virtue of mathematics.

At the very least, the idea that goodness reduces to entropy gradients seems to need some explanation of how entropy gradients result in phenomenal awareness. But such a reduction is also a catastrophic deflation of the ideas CSP is building on from Hegel, since it would seem to cut away the connection between goodness, rationality, and the "true infinite." To the extent that a mechanical process is sort of arbitrarily driving history based on the law of large numbers, it's sort of the polar opposite of what Hegel was getting at. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

I mean, if Aldous Huxley isn't offering a utopian vision of human flourishing, why is that? Because it doesn't offer everything that people necessarily want or it only is focusing on some subsection of what people might want or like while avoiding others.

Personally, I think Huxley's point would have been better served by not having John Savage commit suicide, but simply having him return home. The fact is, all members of the society do seem to get what they want. The rare few who want to pursue intellectual or artistic interests get sent of to their own fully funded Galt's Gulch to pursue their dreams. The rest get to return to the bovine pleasures they were painstakingly engineered for.

But the elevation of pleasure as the sole principle by which the Good should be measured leads to the reductio ad absurdum of absolute utopia being something like human nervous tissue steadfastly managed by AI to produce something like the maximal amount of the infants' simple pleasure in nursing. I think Huxley (and Aristotle) were right that all cognitive function becomes superfluous under such a rubric. The total abolition of any adult level human cognition. Yet I would agree with Huxley that it's ludicrous to suppose that intentionally giving human beings significant intellectual disabilities so that it will be easier to please them is abhorrent and has nothing to do with human flourishing.

Such worlds are completely bereft of beauty. This makes sense if, as Aquinas thought, the Beautiful is emergent from (but not reducible to) the Good and the True. For if pleasure is the sole metric pursued, there is no longer any need for Truth—for theoretical reason—so long as pleasure can be mechanistically provided for. But I should rather like to say that human flourishing involves the theoretical, practical, and aesthetic, as it must for any perfection of freedom.

I'll have to mull that over but this stuck out to me:

But neither is it a realist position in the sense that it does not assume ethical and moral rules given once and for all like in Plato

This doesn't seem like Plato to me. Indeed, Plato says words cannot be used to bring one to knowledge of the Good (Republic, Letter VII). This seems more like the post-Humean Enlightenment project of thinking in terms of "rules all rational agents will agree too." But I think this is quite a bit different from the classical view of ethics, which focuses on the virtues. For one, the virtuous person enjoys right action. They don't need coercive, external rules. -

Pragmatism Without Goodness

I get this view but it seems kind of trivial to me because clearly what is "objectively good" depends on each specific context and what people happen to want and like. Yeah, you could think about that as objective in some sense but it seems kind of trivial.

I don't see it that way. For one, I don't see how "the human good is filtered through context and normative measure," implies anything along the lines of "what is good is reducible solely to what people want and like." The people of the society of A Brave New World certainly like a good deal of what their society offers, but I certainly wouldn't say that Huxley is offering up a utopian vision of human flourishing due to this fact.

That's not the deepest problem though. It doesn't necessarily follow from saying that there are objective things that people like, that an obligation to moral behavior is implied (or that what we call moral or pro-social behavior is good, in other words). Clearly, objective morality has already been presumed. Where does that come from? People just seem to agree that we should have moral rules to guide behavior, and that agreement has probably emerged for various reasons related to our biology and the emergence of functioning societies.

Two things here:

First, assume for the sake of argument that Aristotle is right. There are things we can learn about the human good, and what will make us truly most happy/flourishing. Given this, who would prefer to be ignorant in this regard? Who would want to be profoundly misled about the nature of the world and themselves and to hold false beliefs that would make them unhappy? Would someone freely choose what they consider to be the worse? Would they intentionally choose to be unhappy? And here, I don't mean choosing between goods such that one is unhappy, but choosing to be unhappy simpliciter, to live what the person themselves would acknowledge to be an unhappy and unworthy life, a "bad life?"

I would say the answer to the above is no, which in turn seems to answer the question of "why should I do what is good?"

Second, you do raise a good point. As Moore notes, we can always ask of something "but why is it good?" or "is it truly good?" without a loss of coherence. Questions of practical reason are "open ended." But Moore misses something pretty important: this is just as true for aesthetic reason and theoretical reason. We can always ask "but is it truly beautiful?" or "why is it beautiful?" We can always ask of any proposition "but what if it were false?" People do this all the time. They doubt reason itself. This is the bread and butter of radical skepticism. "But what if modus tollens is a bad inference rule?" "But what if something can be true and false?" These go along with "what if other minds don't exist?" or "what if the world is flat, or ruled by aliens, or a simulation?"

Reason is transcedent. It allows us to go beyond what we currently are, beyond current belief and desire, in search of what is truly good and truly true. This is why Hegel sees it as our link to the true/good infinite. This is why Plato thinks the rational part of the soul has rightful authority and why only it can unify the soul. If open endedness is a knock against the existence of the Good, then it is just as much evidence that Truth cannot exist either.

Maybe you could still call it objective good, but it is pretty flimsy given that not everyone might agree and that people can and have engaged in different moral behaviors in different places and times.

People can and do disagree about the germ theory of disease, evolutionary theory, or the shape of the Earth. Not only that, but such beliefs are socially and historically conditioned. If you grew up in a great many social settings, you likely assumed the Earth stayed still and the Sun moved around it. Does the existence of disagreement about these facts, or that agreement is socially and historically contingent, make the Earth's rotation around the Sun subjective or only objective in a trivial way? -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

In a search for an objective object, yes, I want that. Seems completely impossible, so the conclusion is that all these things are but ideals.

I would agree to that, with the large caveat that "ideals," (inclusive of the accidental properties of particulars) are generated by the physical properties of objects, which include (perhaps irreducible) relations to minds. So, I think that is the right conclusion, just not in the sense that objects exist "only in the mind." Objects exist in as a function of the relationships between minds and the things that lie outside them.

Baring some sort of solipsism, ontological differences have to underpin phenomenal differences. This would be true even for Berkeley. And "physical" seems to be a good concept for denoting how these differences exist. -

My understanding of morals

Several others on this thread have made similar comments. I've responded with this quote from "Self-Reliance."

And if your nature includes being self-determining to some extent? That would seem to entail that Emerson must choose who he is a child of.

Of course, if the Good is truly "better" it would seem that one only ever chooses to become a "son of the Devil" due to either a defect in self-determination or ignorance. The person who knows the better will choose it if they can. But then the question seems to become: "what is more in one's nature, to be self-determining our to be determined?"

Then there is the possibility of willful ignorance or incontinence, as opposed to the "free will that wills itself." There seems to be a middle ground between perfected freedom, which always chooses the better, and utter lack of freedom, where the partially self-determining person can will their own turn away from freedom. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

You seem to still be approaching the problem from the wrong end. You're taking a cow and looking for a very precise (down to the atomic level) demarcation of that already defined convention.

I am starting with only 'this', an indication of some classically local substance, say the non-air surface (say a leg exoskeletal surface of a 0.1 mm bug sitting on a shirt) upon which the phaser energy beam is focused. Now this beam needs to perform its function to the entirety of the 'object' of which that surface is a part.

Like I said, I don't think this is the wrong direction. How can you possibly demarcate where some object ends without any idea at all of what it is you want to demarcate? The questions are not unrelated and the what of the universal determines the demarcation of the particular. The question of where a particular Borg's feet end and where the floor begins requires a reference to what "Borg" and "floor" are.

If I understand you right, you want some beam to paint a particular bug, pumpkin, etc. and lable them "thing" against some background not labeled "thing." But this is never going to work. Individual things aren't what they are as discrete objects because of some relationship between them and their immediate enviornment that exists at the molecular level without reference to any broader context. Things are what they are as discrete objects because of the role they play in the larger whole vis-á-vis minds. Your "beam" can't determine that role only by looking at the object and it's immediate enviornment. The best you can do is program heuristics for finding such distinctions into it based on already existing demarcations, it can't "go out and find them in objects."

Godel certainly shoots that down, but perhaps it was already shot down by that point.

The widely accepted solution has to wait until the 1980s and Landscapers Principle. The problem for the Maxwell's Demon is that erasing its memory so that it can overwrite it increases entropy.

The point is, the whole of the empirical world in space and time is the creation of our understanding, which apprehends all the objects of empirical knowledge within it as being in some part of that space and at some part of that time: and this is as true of the earth before there was life as it is of the pen I am now holding a few inches in front of my face and seeing slightly out of focus as it moves across the paper.

I personally think this is a view that comes around from accepting very bad, and often unchallenged metaphysical assumptions that Kant inherited from Locke and some of the other empiricists.

It sets up a false dichotomy between "things-in-themselves" and "things-as-known." The correct dichotomy would be something like: "things-as-they-relate-to-everything-but-mind," and "things-as-known."