Comments

-

"Aristotle and Other Platonists:" A Review of the work of Lloyd Gerson

The question of what he knows is left open. Where does he imply that he and others have knowledge of the forms?

I shared them and bolded the most relevant parts earlier. There is a reason "skeptical Plato" theorists, from what I have seen, almost always deny the authenticity of the letter. At the very least, the letter decidedly does not say "I write no doctrines because I have none," let alone "I wrote no doctrines because I know nothing."

But Socrates does not pretend to know what he does not know. In the passage from the Republic he does not say that the way things look to him are the way they are. He says that a god, not him, knows if it happens to be true.

It's not a question of Plato's Socrates, it's a question of Plato the author. If Plato is a skeptic and doesn't think he really has any good idea what the Good is, why is he writing things that are so suggestive and have been overwhelmingly understood as saying something quite the opposite? To pragmatically move the dial on policies he prefers? (but of courses, not ideas he knows are good, since he is a skeptic). This would seem to put him right in with the Sophists, fighting over who gets to mount their shadow puppets over the fires of Athens. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

:up:

Agree 100%, those are the points I've been arguing for.

It would be nice, yes. We're 150 posts in here, and no such middle ground that holds water has been suggested yet, but I'm open to it.

Any suggested bound is going to be put to the test of one of my OP examples, or the Midas thing.

Dontcha think this might have to do with the standards all being magical devices? Harry Potter's magical tent that is bigger on the inside than the outside causes similar problems (does it shrink things or create a wormhole or what?) without involving delineating anything. The magic might be the problem.

This was, in fact, the problem with Maxwell's Demon. It took a very long time to figure out why it couldn't exist, but finally people thought to challenge the assumption of the thing essentially having a non-physical/magical memory.

If the idea can't do that, then it doesn't seem to help.

I think it does. It tells you that pipes, sheep, cars, etc. are not defined by particle ensembles. They're defined by a set physical properties and their relations to mind. If you zoom in to the scale of particles, you have generally already left these sorts of macroscopic objects behind.

Think about it this way, if "being a pipe" or "being a cow' is "strongly emergent" or something like that, then it's quite impossible to determine if some particle belongs to a cow, etc. or not. The phenomena in question simply does not exist at those scales. This doesn't mean that we cannot say such things are "made up" of molecules, atoms, etc. It says we cannot reduce them, or their boundaries, to such things.

Delineating things in terms of building block particles seems to presume a certain sort of reductionism, but it's such a common view that I think this often goes unacknowledged. -

Flies, Fly-bottles, and Philosophy

Sure, but the two don't collapse into one thing. There is still a worthwhile distinction to make between etymology and looking through a microscope. They're phenomenologicaly distinct too. No one mistakes a rock or bee for a word as far as sensory experience goes. -

Flies, Fly-bottles, and Philosophy

It is better to think that a word has the meaning someone has given to it than to think that the meaning of a word is an eternally existing (subsisting entity floating about in some alternative world. But at face value, for those of us using the words, that is simply false. We learn what words mean - we do not make it up; we discover what they mean (what the rules for its use are), or we do not learn to speak. So there can be a scientific investigation into what the word means - and how its meaning changes. To be sure, sometimes we know who gave a word its meaning, but even if it was coined by someone, its use is the result of a process of dissemination which is rarely documented and we do not altogether understand. But dictionaries often include remarks about it and it could be the object of a "scientific" investigatio

What's interesting is that the bolded is true in two senses. First, there is etymological analysis, looking at old texts to determine how some term came to mean what it does. But second, there is looking into the actual physical referents of words to see what they are. So for instance, we know a lot of things about water that we didn't know in 1700. Even grade school kids know that water is H2O.

In the first example, we are talking about scientific inquiry into the history of social practices. In the second we're talking about the natural sciences. The natural sciences in turn often do shift what we even mean by our words. "Water" used to refer generally to any mass of mostly H2O, inclusive of all the stuff dissolved or floating around in it. We still definitely use the word in that sense, but it's also not uncommon today to use it to refer specifically to H2O, and to count anything else as a modifier ("salt water") or different substance. But that only makes sense, science effects how we think of things. Unlike Melville, we don't call whales fish anymore either, but that required knowledge of evolution to pin down decisively. Now preschoolers know "fish" doesn't refer to "whales." The evidence of genetic lineage ended up driving convention.

And why can't a philosopher do this, instead of sitting around and describing how the term is actually used.

That was Marx's point on Feuerbach: "philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it!" - -

"Aristotle and Other Platonists:" A Review of the work of Lloyd Gerson

Just to return to this, you have not answered why Plato, in his letter, when he clearly has an opportunity to present himself as a skeptic, instead chooses to say something very different, and even implies that he has shared knowledge of the forms with others (although not through dissertations.)

The Seventh Letter might not have been written by Plato, but it was decidedly not written by a skeptic.

Your reference to the Phaedo also doesn't say what you say it does in context. He doesn't call the forms "foolish" at 100. Rather, Socrates is making an argument for the immortality of the soul based on the assumption that something like the theory of forms is true. That is, he is (perhaps foolishly, or seemingly so) not going to justify the forms here again, but will show what follows from his understanding of them.

Plato does have Socrates say something to the effect of: "no one should take this exact narrative too seriously and think these things are just as I have described them," but this would seem to be a reference to the images he is painting. Like he says in the letter, you can't put this stuff into words. This is why he uses many different images to try to get the ideas across. This is why Socrates repeatedly demures from speaking on these issues directly, because they cannot be spoken of. The warning then is to not mistake his image, appearance, for the reality he is directing our attention to. It isn't to say something like, "and I actually don't know if any of this has any real merit because knowledge of such things is impossible, so don't take me too seriously."

And it's worth noting that "opinion" is in some ways a very inadequate translation of doxa. Today we tend to think of opinion as subjective, as having no real grounding outside itself. But doxa refers to images or what things "seem to be like." What things "seem to be like," is an important parts of what they are. The divided line is all one line, rather than two discrete lines, for a reason. Appearances are part of reality. The line is a hierarchy. To know such appearances, to move up the line, to know something of the truth (in the way the English "knowledge" is colloquially used). Plato's use of doxa has none of the connotations of the English "opinion," where we might think that "to only have opinion" means to lack any knowledge and understanding of a thing.

Again, if Plato knew nothing of the Good, but is just spinning tales based on pragmatic usefulness (a pragmatic consideration based on... what? he doesn't know anything of the Good right?) then would be acting like the very paradigm of the Sophists he criticizes so heavily. He would be someone who pretends to know what he doesn't know and who uses words to try to manipulate people for his own pragmatic ends. -

How would you respond to the trolley problem?

Lets say person A murders person B, is person C now responsible?

It depends. If person A is a child and person B is an infant, and C could very easily have stopped the act? I don't think you can get a free pass on allowing some little kid to throw their baby sibling into a pool (with or without malice) just because you do not want to get "involved." -

Purpose: what is it, where does it come from?

No, as explained above, they cannot be "all ideas", or else there would be no truth or falsity about what the earth and moon are doing with each other, and what the earth and sun are doing with each other. Your perspective is known as Protagorean relativity. Your ideas about what these things are doing are no more true than mine, even though they are completely different, because there is no truth, it's just ideas, yours mine, or whoever.

This reminds me of the opening of G.K. Chesterton's Orthodoxy, where he talks about how "no one is more rational than the mad man." Everything is explained rationally for the person with paranoid delusions. Why did that person in the street fold his arms just then? To signal another conspirator. Why wasn't my newspaper delivered today? The conspiracy. Why am I being taken to an institution? Well that is just exactly what would happen if I truly was the rightful King of Britain and a group of people were trying to keep me from making my claim!

The solipsist who thinks they are God has a reason for everything. The paranoiac as well. The problem often isn't a lack of rationality but a surfeit, tightly packed into a very small world, an ever shrinking circle that contains, for that person, everything.

Edit: I should probably note that I didn't follow the whole interchange there, just that part. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

I'll have to get around to reading that some day. It sounds like a good one.

That wording makes it sound like there's one preferred border, when in fact there is an arbitrarily large number of ways the border can be assigned, none better than any other. There is no 'this border'. There is only 'a border', among many other possibilities

Isn't there a middle ground between there being "one canonical border," and any assignments being arbitrary? If assignments were truly completely arbitrary then people should make such distinctions at random. But they clearly don't do so. So wouldn't it make sense to look for the object in exactly what causes people to delineate them in such and such a way in the first place?

Moreover our concepts vis-á-vis objects have been refined throughout history, and they often tend to be refined by the sciences. That is, people's understandings of which boundaries are relevant, which distinctions we should keep, and which are spurious, seems to unfold from a very close examination of (potential?) objects. This to me says the properties of the objects themselves play a very large role in determining how we define and delineate them, even if this always occurs through their relationships to minds.

That sounds somewhat like idealism as well and I totally agree with it. Something (humans, whatever) finds pragmatic utility in the grouping of a subset of matter into a named subset, which is what makes an object out of that subset. That's the similarity with idealism. But if I am correct, idealism stops there. Mind does not supervene on anything. There's no external reality, especially a reality lacking in names and other concepts to group it all intelligibly. There is only 'cup', and no cup.

Idealism leads to solipsism. Intellects sharing categorization via language does not.

Depends on the type of idealism. Plato and Hegel, who often get labeled "idealists" do not in any way deny the reality of rocks and trees or the existence of nature outside of individuals' awareness of nature. In a lot of ways they are a lot more "realist" about external entities than modern Kant-inspired theorists, who often instead have it that all intelligibility in the world is the sui generis creation of minds.

But ideas might be said to be "more real." Here is one way to think of it:

Things might have a lot of different relationships. Salt can interact with all sorts of stuff. So can pumpkins, etc. However, over any given interval of time (some spacio-temporal region) any thing only actualizes a very small number of its properties. Salt only actualizes the ability to dissolve in water when it is placed in water. It only reflects wavelengths of light so as to appear white in a dark room. It only "appears white" to a person when a person looks at it under "normal" (full visible spectrum) light conditions. So, during any given snap shot interval, very few of a thing's properties are being actualized (and in "no time at all" no properties are being actualized, except perhaps some sort of bare "existence").

Only in the mind of the knower do things exemplify (potentially) all their properties at once. Water can become ice or steam, but it doesn't do both simultaneously. But the mind can know that water freezes and boils, it can know that salt does all sorts of different things in different contexts. In this way, things most "are what they are," when they are known.

If things are defined by their physical relationships with other things, then it is their relationship to human minds, which carefully examine and triangulate all such properties through things like science, that seems to pull together what they are the most. And I think this is what Hegel gets at in his doctrines of notion and concept, as well as the idea that objects and their related concepts are mutually self-consituting. Robert Sokolowski gets at how this works historically from the Aristotlean and Thomist perspectives as well.

It's worth considering that before the rise of "the view from nowhere" as the gold standard of knowledge the gold standard was "the view from the mind of God." Such a view isn't defined as "reality versus mere appearances" but rather as absolute, and so including appearances (the sum total of ALL appearances thus being included).

Right, and our current set of "objects" has been built up from millennia of observations and close inspections of physical interactions. Cultural inertia certainly plays a role, as does "what seems intuitive by nature" but I don't think there is any reason to think we are incapable of hitting on better and better distinctions. Technology is sort of the proof of theory. It doesn't prove that any theory is "the one true absolute standard," but it tends to suggest that it gets at least SOMETHING right. We might radically change our concept of lift in the future, but it's going to be something consistent with the fact that the current theory lets us build flying machines. -

Reading Przywara's Analogia EntisWell, I've been a bit busy so Chapter II might be a bit. I wanted to have at least some brief intro to the Transcedentals since the book simply assumes you have some knowledge of them.

Interesting, I will have to check that out. I've sort of come to the opinion that a lot of interesting work in information theory and the philosophy of information (heavily analytic for the most part), the use of IT and complexity studies to unify the sciences (including the social sciences), and the popularity of pancomputationalism in the physics community (and biology to some extent) in many ways represent a vindication of a lot of important ideas in scholastic thought and Hegel (a relational view of ontology in particular). I'm always looking for more ammo.

I have not been able to find anyone making this connection though. In part, I think it's hindred by the fact that Catholic philosophy, which does the most to update scholasticism (rather than just sticking to historical analysis) tends to be somewhat estranged from analytic and heavily science focused philosophy (at least in comparison to Continental thought). -

The Argument There Is Determinism And Free WillIf freedom is defined in terms of potency, as "the potential to do anything," then determinism is a grave threat to freedom. Such definitions often define freedom as "the ability to have done otherwise," and in a deterministic frame this seems impossible. Locke would be a good early example here. He has human freedom ensured by a sort of sui generis "veto power" on action, one that seems to be absolute and unconditioned.

But the difficulty here is that the proponent of such a definition of freedom still wants to say that the world in some way determines our actions. We can't be free to "jump into a river to save a child," unless the child's being in the river can condition our actions in at least some way. Likewise, we preexist our individual choices and we'd like to say that "who we are" and "who we have chosen to become" in some ways affects our actions. Our memories are prior to actions, yet we would like to think they affect our actions. If they didn't, our actions would be arbitrary.

To my mind, this is just a spurious definition of freedom. If one takes the classical view of freedom as the "self-determining and self-governing capacity to actualize the good," a host of thorny issues dissolve. Yet this view is often rejected precisely because people are already committed to the idea of freedom as potency. They claim that the good must be thought of as completely unconditioned, something we are free to define however we want, as an act of pure will, precisely because this is what ensures freedom. So the thinking goes, if the good is already in some way definite, then our pursuit of the good (practical reason, pragmatic concerns) ends up being determined, and in turn this makes us unfree because freedom is the ability to "do anything." Taken to an extreme, this view makes all government, all human relationships, marriage, parenthood, all moral teaching, etc. a constraint on freedom, rather than its perfection.

Nagel's view on the absurd can even be taken in this light. Seeing everything as comical, and in a way ridiculous, allows us to avoid the constraints of caring too much about anything. Imagine Gandalf hitting a pipe as he watches the armies of Mordor set to bring darkness upon the world and quipping his Hobbit companion, "do not worry, for nothing really matters and nothing is truly dark or evil."

(Note: you could obviously take Nagel differently. I vastly prefer his take to Camus or Sartre at any rate) -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

What is pragmatic depends on how a particular animal lives its life.

Yes, which is determined by the way the world is and the nature of the animal. No tiger becomes a vegetarian. Any tiger stuck in the desert likely dies without reproducing. No ant foments revolutions. The sheep distinguishes "wolf" for a reason. Humans are more self-determining than beasts, but they are not, by nature, completely self-determining.

So what determines the pragmatic is, to some extent, already given, and this explains why different peoples make largely the same sorts of distinctions despite having developed their languages and cultures largely in isolation.

I'm not sure what the counter point here is supposed to be since you have once again posed your objections entirely in terms of potency and not given any examples of actual occurrences. Everything is "could, "can," "is possible," or "if." But can you think of one culture that doesn't distinguish types of animal or doesn't use terms for colors but rather blends color and shape, color and size, etc.?

I don't know of one. If they ever existed, they have either gone extinct or at the very least occupy a marginal position in terms of world languages.

But my point is exactly this, which languages, norms, and distinctions become dominant is not something determined by "no reason at all," or simply because "people choose them." There is a causal chain driving language evolution, history, human distinctions, etc. Of human choice was completely free of "how to world is," then distinctions should look essentially random, since they are conditioned by nothing. If they are conditioned by "pragmatic" concerns, then it would seem that such concerns are themselves determined by "how the world is" and "how people are."

Now if you have a libertarian view where human choices are not determined by the world—are essentially free from causality—then obviously that's where our disagreement lies. But if human choices are "not caused" then it would seem hard to me to explain why they appear to be.

But if you acknowledge that human choices do have causes, then I'm not really sure what the objection is supposed to be. Is the claim that the properties of objects don't play a determinant role in distinctions? That what is considered "good" has nothing to do with either the properties of things or human nature?

I've long had the suspicion that appeals to "pragmatism" that also deny any objective reality or determinateness to "what is considered good," are in danger of vicious circularity. Everything ends up malleable, determined man's practical concerns, but then the Good itself, the target is practical reason, turns out to also be something that is "pragmatically" determined? Then everything seems to be "pragmatics" all the way down, in which case distinctions and choices should be arbitrary. But they don't appear to be. -

Mathematical truth is not orderly but highly chaotic

That should read "countably infinite." We can think of endless permutations of language, but we could also spend and infinite amount of time saying the names of the reals between any two natural numbers. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

:up:

I'm also not sure why it would be important to define individuals "without any reference to their relations to minds," in the first place. For one, this seems to make the task impossible, because you've now cut any possible relationship through which we could know anything about individuals. The second thing would be: why do this in the first place? The "view from nowhere" has been beaten about as badly as any philosophical position out there. Reductionism hasn't planned out despite over a century of efforts, and I honestly think you can make a good case for it being decently well falsified. Minds are obviously "real" and so their relationships to things, including demarcating them, seem like they should be plenty "real enough" to define individuals.

Shouldn't "things-in-themselves" be impossible to cognize by definition? If it's being cognized then it's always cognized "as it relates to that mind" not "as it relates to nothing but itself." Most uses of the term I'm familiar with set it up this way at least—Locke, Kant, etc. make them unreachable by definition (and then have them do a huge share of the explanatory lifting in their explanations of the world anyhow, lol) -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

Take for example a typical free body diagram. Such a diagram is a human construct depicting hypothetical physical objects connected in various ways and applying forces to each other. Take away the human semiotics, and all that is left is a classical physical system of particles, the motion of each being determined by the net forces acting upon them. No part of that description demarks object boundaries, except at the 'particle' level.

Well, to make things worse, I've seen many physicists and philosophers of physics call into question the idea of even particles as discrete objects, i.e., "they are human abstractions created to explain measurements" etc. I do not think you're going to find what you're looking for. In physics there are no truly isolated systems and when you get down to the scale of atoms entanglement adds another wrinkle to looking for discrete entities.

Your description has already demarked the sheep by selecting "the exact make-up and location of every particle in a sheep". The object at that point has already been defined, despite not stating that the object constitutes a sheep.

Yeah, that's the point. Even if you somehow were magically given what you knew to be the canonical "mapping" of some entity, that, taken in isolation, couldn't tell you what it does in the world and how it relates to it (i.e. what it is). Which ties into this point:

Remember that I'm more interested in where the pumpkin stops than what it is. My wording (that you quoted there) attempts to convey that. "What things are" does not, and such wording already presumes the preferred grouping of this particular subset of particles.

IMHO, the two questions cannot be pulled apart.

How can you tell where a given pumpkin ends if you don't know what a pumpkin is? You can't distinguish between the pumpkin, which is full of water, and rain running off its surface, unless you know something about what pumpkins are. Likewise, if you had a human body and knew nothing about it or what a hand was, how could you possibly demarcate the hand? You couldn't. Clearly there is a physical basis for hands being distinct parts of bodies, but it can't be found in the hand itself.

Anyhow, you keep framing things in terms of particles. People have been trying to give this question an even somewhat satisfying answer in terms of particles ensembles for over a century now. I think it's just a fundamentally broken way to conceive of the problem. You don't get any discrete boundaries if you exclude any reference to minds. All other multiplicity in the world is dependent upon the multiplicity of minds, a mindless world is just one continuous process, a "blobiverse" as I've seen one physics article put it.

At the same time they depend on how your biology happens to be. If you had a different type of color vision then what decomposition of colors seems "natural" may not be the same as a regular person. At the same time, if you had a sense that was inherently able to detect "size + color" then you would have a completely different conception of what seemed "natural".

Yes, exactly, but humans aren't many potential species, we are just one. What is "pragmatic," "useful," or "good" is always conditioned by the way the world is. This is what I mean by prioritizing potential over actuality.

Of course, if the world was so different as to rewrite all our conceptions of objects, there would be different objects. But the world would seem to have to be very different indeed. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?BTW, a similar delineation problem occurs when trying to define computation in physical systems. You can map all sorts of computations onto all sorts of physical systems. There is no one canonical mapping. This is why folks like Terrance Deacon arrive at the conclusion that life is required to make sense of information (although I disagree with this view).

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/computation-physicalsystems/#SimMapAcc

The simple mapping account turns out to be very liberal: it attributes many computations to many systems. In the absence of restrictions on which mappings are acceptable, such mappings are relatively easy to come by. As a consequence, some have argued that every physical system implements every computation (Putnam 1988, Searle 1992). This thesis, which trivializes the claim that something is a computing system, will be discussed in Section 3.1. Meanwhile, the desire to avoid this trivialization result is one motivation behind other accounts of concrete computation.

Likewise, you can encode an MP3 song into all sorts of media: DNA, discs, tapes, even rocks or water pipe valves. But what makes that encoding that song can never be found in the encoding or the objects in which it is encoded themselves. It's a relational property.

The corpuscular view has many difficulties here. For one, in an a deterministic universe of little balls of stuff bouncing around, where the little balls define everything, information theory becomes difficult to conceptualize. There is no real "range of possible variables" for any interaction. The outcome of any "measurement" (interaction) is always just the one you get, there is no "potential." The distribution relevant for any system is just that very distribution measured for all the relevant interactions. You need some conception of relationality, potency, and perspective to make sense of it (Jaynes arguments for why entropy is, in some way, always subjective I think are relevant here). Arguably, you need perspective to explain even mindless physical interactions, but the legacy of the "view from nowhere/anywhere" is strong. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

Don't care. The question is, why should anything from physics prefer this particular subset of particles which humans collectively describe as 'pumpkin'?

Depends on what you mean by "from physics?" Obviously, people do recognize things like pumpkins and even cultures that developed largely in isolation from one another make distinctions that are far more similar than dissimilar. Presumably, the causes behind the emergence and development such distinctions are physical, and the reasons for their being similar are also physical.

Actually, we have a pretty good history of the development of many of these notions. We know how people have probed questions like "what is water?" and "are whales fish?" for millennia. Any explanation of the development of these concepts is going to involve the myriad physical observations people have made of said objects and their careful examination of their physical properties and physical relations vis-á-vis other entities (e.g. through experiments).

Hence, I'd argue that object clearly plays a role in the development of the concepts associated with it, and this role seems to flow from its physical properties and relations. So in that sense, the distinction does come "from physics," and indeed in an ontology like physicalism it seems to be a requirement that all such distinctions can be explained in terms of physics (although perhaps they are not reducible to physics—whether "non-reductive physicalism" is a coherent concept depends on how physicalism is defined).

But if you want an explanation in terms of the subject matter of physics, or in terms of some superveniance vis-á-vis "a set of particles" (which is not necessarily how "physics" would like to define things anyhow) then yes, the object can never be defined "from physics." This doesn't mean that do not objects exist, it means that trying to define them in terms of ensembles of particles won't work. In general, I think the focus on particles as "building blocks," and the desire to define things in terms of them, while quite ancient and still popular, is based on fundamentally flawed assumptions.

So:

Mathematically, any subset is as good as another, so there's no correct answer to 'what one subset of particles is this particle a member?'. Absent a correct answer to that, there doesn't seem to be an objective 'object'.

See: https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/912501

Asking for objects to be defined in terms of sets of particles is like trying to figure out what the letter "a" is, what it does, and how it should be distinguished from other letters/the background, by only looking at the shape of the letter, the pixels that make it up, etc.

I'd argue that the question: "why should anything from physics prefer this particular subset of particles which humans collectively describe as 'pumpkin'?" is simply the wrong sort of question and itself presumes things that I don't think are true— namely that "what things are" is completely a function of "what they are made of." But consider what would happen if you moved a volume of water to a parallel universe with slightly different physical constants. Perhaps "water" as defined as "H2O" can still exist there (if we define H and O based on their atomic numbers), but it might have completely different interactions with everything around it and between parts of itself. For example, a few tweaks get you water where the solid form is denser than the liquid form, which in turn would seem to make life much more difficult to form (an example often given for "fine tuning). But if something has totally different properties, how is it "the same substance?" I would say it isn't; change the fields and you get different things.

All the properties of objects are relational (e.g. lemon peels don't reflect yellow light in a dark room, salt only dissolves in water when placed in salt). Non-relational properties, the properties things have when they interact with nothing else and with no parts of themselves, are, at the very least, epistemicaly inaccessible. Such "in-itself" properties can never make any difference to any possible observer. Hence, Locke made a grave mistake on making "in-itselfness" the gold standard of knowledge, and this culminates in the incoherence of the "view from nowhere." Looking for "what things are" without reference to their relations then is never going to work.

Objects are defined in terms of their relational properties. Things' relationships with minds are often denigrated as somehow "less real" than relations between mindless things. However, I don't think there is much to support such a view. It's based on presuppositions that I think it is difficult to support, and a sort of (often unacknowledged) dualism.

Note that I switched to 'objective' there instead of 'physical', which is dangerous because the word has connotations of 'not subjective' and has little implication of 'not subject to convention'.

:up: Right. That the bishop always moves diagonal is a convention but it's an objective fact. But presumably it's also a fact with physical causes and underpinnings.

I have an autistic son, and such conventions are not so obvious. You point to something, and he's not considering the thing being pointed to. He's looking at the end of your finger, wondering what's there that you're talking about. Not all conventions we find so natural come naturally to someone not neural-normal.

The atypical can only be defined in terms of the typical. That something is "convention" does not make it arbitrary. Barring some sort of libertarianism where man's actions are unconditioned by the way the world is, there is presumably a causal chain behind conventions. And that conventions synch up so well, even when developed in isolation, and that their historical evolution is demonstrably driven by physical examinations of things, I believe demonstrates that the conventions surrounding objects are determined by their properties. I mean, what is the alternative, that conventions re objects don't have anything to do with objects themselves? Do they spring from the aether then? Presumably something about "tiger" makes it an important distinction for all peoples who encounter tigers to make, in a way that grue or bleen are not.

Perhaps, but your prior post seems to be elevating potency far above act in the analysis. No one uses grue and bleen and I don't imagine you could ever get them to, not least because:

A. It isn't obvious when objects were created by looking at them, smelling them, etc.

B. When an object is "created" is itself a dicey philosophical question.

But you might imagine something like splitting the visible spectrum in half and having words for size AND color for some colors and then shape AND color for others, such that "square + purple" and "yellow + small" are their own discrete words. And yet absolutely no society does this. They use colors and sizes.

It is of course logically possible for conventions to be very many ways. But in actuality they aren't. Presumably, this is not "for no reason at all" and I also see no reason to think it comes from some sort of sui generis and spontaneous uncaused freedom unique to man. Hence, convention cannot be arbitrary but emerges from the interaction between man and the world, something that is presumably "physical" in an important sense and involves the properties of objects in conjunction with human nature and culture. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

Whether it's duck or rabbit is not present in the picture.

Yes, exactly. That's s the way it is for things. You could know the exact make-up and location of every particle in a sheep and this, taken by itself, would not tell you that it is a sheep or what a sheep is. It's the same way that you can't tell what the bishop does in chess just by staring at the piece really hard. Likewise, such "complete physical information" about a cup of coffee also wouldn't even tell you if it is hotter than the ambient enviornment (and thus was made recently), and it certainly wouldn't tell you what a cup is or what coffee is. And if you don't know what a cup or coffee is, how can you possibly tell where one stops and the other begins?

You can't get to what things are without reference to context. That's issue of determining universals. However, in the same way, you can't delineate the boundaries of anything without the idea/universal. The idea is what tells you "include this, not that," or "stop here."

That's why looking for such delineations "in physics" without reference to things' external relations makes no sense. To be sure, all these relations are presumably physical, but the relations don't exist "in" the things. E.g., Salts' ability to dissolve in water isn't properly "in" salt, for salt only dissolves when it is placed in water, not when it is off by itself. Things' external relations, particularly their relations to minds, determine "what they are." Then the idea of what they are delineates their boundaries. But it's silly to talk about whether individual atoms are "part of a cat," because a cat isn't defined in terms of ensembles of atoms but by relations to move, to litter boxes, to people, etc.

However, the idea that things must ultimately be definable in terms of what they are "built up from" remains strong in modern philosophy, and so people keep looking for "catness" in groups of atoms and for the boundaries of individuals cats in "clouds of atoms."

To borrow a line from J.S. Mill, I think one would have had to make some significant advances in philosophy to believe that children experience statistics and not things (or have had some very strange childhood experience.) The things of experience are given. Questions about what underpins them is another matter. -

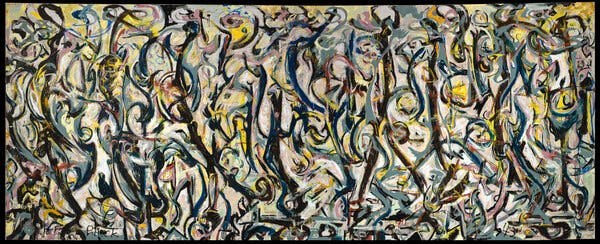

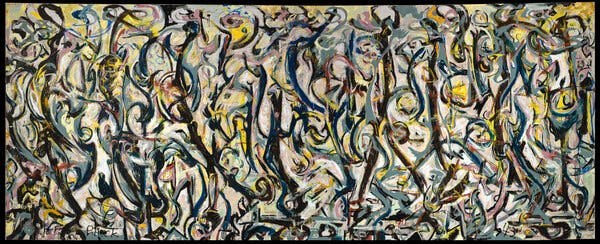

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?I also think this gets at why AI images full of unrecognizable images are generally taken as "creepy" or "disgusting."

Whereas abstract art can be quite lovely:

-

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

There isn't a scientific definition of life according to Robert Rosen. If pressed to come up with one, we'd have to say it has something to do with a final cause, but this isn't something we find in the physical realm. Plants have chlorophyl, but so do euglenas, which aren't plants or animals. We can't say plants don't eat, because Venus flytraps do. It's fuzzy boundaries.

Right, there is not a perfect physical definition, but there is certainly physical evidence for such definitions. Conventions could be different. They sometimes are from place to place or time to time. But they only tend to differ so much, and they don't develop arbitrarily, but rather develop in line with sense evidence (physical evidence). Historically, things obviously help to develop the notions that they can be said to instantiate.

Things are defined by their relations, including their relationships to mind.

But look again. Look at the visual field that includes the pumpkin. Feel of the pumpkin with your hand. Smell the pumpkin. Where in any of this data is pumpkin?

It's in there. Otherwise, when kids point at things and ask "what is this?" we should have little idea what they are referring to, since it could be any arbitrary ensemble of sense data. But when a toddler points towards a pumpkin and asks what it is, you know they mean the pumpkin, not "half the pumpkin plus some random parts of the particular background it is set against."

Yet if there were no objects (pumpkins, etc.) given in sensation, kids should pretty much be asking about ensembles in their visual field at random, and language acquisition would be hopelessly complex. The woes of people with agnosia have been enough to convince me that a cognitive grasp of the intelligibility of objects is fundamental to perception. If we had to conciously abstract from and learn the visual ques that represent depth, for example, we'd have quite a time learning to walk.

Even animals recognize discrete wholes; the sheep knows "wolf" and knows it from the time it is a lamb. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

Ha, that's a funny clip.

You're talking about universals, there, so you're starting with a time-honored way of dividing things up.

Aren't they two sides of the same coin? We have evidence to tell us that a plant is different from an animal (universal ). We also have plenty of empirical evidence to support the idea that this pumpkin right here is different from the one "over there on the shelf," namely their different, observable histories, variance in accidental properties, and obviously their appearing to be in two different spaces (concrete).

Likewise, there is plenty of physical evidence to support contentions like "this pumpkin here is the same pumpkin that was here last night." Yes, the pumpkin has changed overnight, so we might consider if it is really the same pumpkin, but nonetheless, we still have physical evidence that to help us distinguish what we mean by "this pumpkin that has been on the shelf all night." For instance, a video of the pumpkin sitting on the shelf all night is such physical evidence.

If there was absolutely no physical evidence to demarcate particulars then decisions about them would be completely arbitrarily, and it should random whether I consider my car today to be the same car I drove last month. But our consideration of particulars isn't arbitrary, nor do they vary wildly across cultures, even if they can't be neatly defined.

I think the problem here is the same problem I referenced before, wanting to try to define objects, delineation, continuity, etc. completely without reference to things' relationships with Mind ("Mind" in the global sense since this is where concept evolve). -

Mathematical truth is not orderly but highly chaotic

Noson Yanofsky's book on this subject sounds quite interesting, it's been on my reading list. Still, from what I understand of his thesis, I don't think he is trying to motivate any sort of thoroughgoing rejection of "science" as a tool for decision-making or developing knowledge

It is very convincing, because it sounds scientific, and because it insists that it is scientific, and especially because you will get burned at the Pfizer antivaxxer stake if you refuse to memorize this sacred fragment from the scripture of scientific truth for your scientific gender studies exam

Now, this might be a bit of hyperbole, no? Didn't the NHS itself publish a study suggesting that vaccination might not be a net positive for young British males, even if it was still warranted due to its downstream effects on overall population health?

And no one got arrested for selling people all the horse dewormer they wanted to gobble down. I happened to catch it live when our former President proclaimed that he was "on the hydroxy right now" despite not even being sick, and he seems fairly likely to become POTUS again, rather than having been burnt alive. -

Mathematical truth is not orderly but highly chaotic

The set of finite-length strings over an at most countably infinite alphabet is countable. There are countably many strings of length 1, countably many of length 2, dot dot dot, therefore countably many finite strings.

If you allow infinite strings, of course, you can have uncountably many strings. That's the difference between positive integers, which have finitely many digits; and real numbers, which have infinitely many. That's why the positive integers are countable and the real numbers uncountable. It's the infinitely long strings that make the difference. But natural language doesn't allow infinitely long strings. Every word or sentence is finite, so there can only be countably many of them.

This was my first thought. Natural languages would seem to need to be computable, which would entail countably infinite. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

But that's an answer isn't it?

Certainly. Like I said, multiplicity is given in experience, and this doesn't seem to be arbitrary. Yet you're not going to get canonical dividing lines between objects in physics. This jives well with classical arguments for the necessary "unity of being," (Unum as one of the Transcedentals). If you had a "second sort of being" that didn't interact with our sort (even mediately), it would be epistemologically inaccessible and, by definition, its existence or non-existence could never make any difference for us. All being then, or at least all being that isn't a completely inaccessible bare posit, shares in a sort of unity where everything interacts with everything else (even if this interaction is mediated in some cases).

But we could consider that an AI or machine could distinguish things based on form. A machine charged with eliminating White Snake's "Lonely Road," could identify it in disparate media: on magnetic tapes, in sound waves, encoded on hard drives or compact discs, or even encoded in in neurons. That is, we can define things in terms of substrate independent relationships (information). Yet a machine could obviously also distinguish between a magnetic tape and a sound wave by other means.

Form, at least form as information, seems to be definable in complete mathematical abstraction, but there are still problems with it. If we change one note in White Snake's song is it the same. What about covers? What happens if we keep losing fidelity until it becomes indistinguishable from many other possible recordings?

So on the formal side there is an inherit instability and ambiguity too, precisely because form can be so precisely defined that minute changes constitute new mathematical entities. Thus, we might want to allow for such ambiguities and variance in form by looking at key morphisms that would allow for a mapping across similar entities. But which morphisms matter? Again, the mind and its relation to the object seems essential for defining this.

This back and forth instability reminds me of the sort of things both Hegel and Pryzwara like to deal in. I do think Hegel's doctrines of essence and concept represent a good answer here, but they are a bit much to get into. Ultimately, concepts are determined by what a thing is, but what a thing is includes its relation to Geist/mind. Concept and delineation evolution aren't arbitrary but evolve as part of what things are (which includes how they are known) .

I don't think so. There's no physical evidence behind the way we divide the world up.

None at all? It seems there is plenty of physical evidence behind the distinction between plant and animal, living and non-living, physical squares and physical triangles, etc. The problem is, to my mind, not lack of physical evidence for our distinctions but rather the desire to want to define the objects of knowledge without reference to the knower or that knowledge's own coming into being. It's the problem of presupposing a certain sort of atomism.

Well, this is the old problem of The One and the Many, no? Being has to be a unity of sorts, but there has to be some way to affirm multiplicity or else we end up like Parmenides, unable to affirm anything, only able to speak the all encompassing Eastern "ohm." But everything can't be completely discrete or arbitrary either, or else we also can't say anything about anything.

I do think the univocity of being makes this problem particularly acute, which is why Plato's original solution has a sort of vertical dimension to reality. -

Simplest - The minimum possible building blocks of a universe

Reasonable answer - but I'm going to disagree.

In order to build a computer, the bits have to have specific relationships. There has to be structure between individual bits.

So while bits are notionally simple, by the time you can build anything with them you have stealth included some assumed structure. The bits+structure is less than trivial (simplest).

There is still the potential for a very simple system - but without an explicit statement of the structure, I'm inclined to think you are hiding more complexity than you realise within your implicit assumptions.

I'm sympathetic to your objection. Information is inherently relational, and so of course, for bits to be the building block of even the simplest "toy universe," they must exist in some sort of relationship to one another. A 1 can only be distinguished from a 0 against some background that lies outside that individual bit itself. I think that, properly understood, information theoretic understandings of physics and metaphysics are anti-reductive, since context defines what a thing is, rather than vice versa.

So I guess it comes down to what you mean by "building block." If you take a substance metaphysics-based approach where the properties of building blocks must inhere in their constituent makeup, then the bit isn't going to work. But in a process/relational view, where a thing "is what it does," the bit seems to work fine as a "building block" in that there does seem to be some fundemental level of ontological difference (reducible to 1 or 0 if it is quantifiable at all) underlying any and all more complex structures. Perhaps "building block" is the wrong way to look at it here though. In a certain sense, I think the "entire context" matters for fully defining constituent "parts" role in any universe, and this might preclude things' being "building blocks" at all in the normal sense. -

Reading Przywara's Analogia Entis

I took it that the "formal question" is about where any methodology must begin re metaphysics. Are we to begin our investigation with being or the mind? - essentially. Basically, we can't start saying things about being until we first resolve what we need to start investigating first.

As for "creaturely" it seems to be describing the interplay between physical display and consciousness. Thus I can say, "That is a dog," but I can't experience what it is to be that dog.

Just thinking of how St. Thomas frames it, I think the bigger distinction would be that knowing everything about a dog would only tell you what it is, not that it is. The dog's essence does not account for its own being. We can't say, "ah, of course, it has black fur, thus it must necessarily exist." Any creaturely (and thus contingent) entity needs something outside of itself to explain its existence. Only in God is existence explained by essence, since God is being itself (Ipsum Esse Subsitens). Another way of putting this is that creatures are not subsistent. Their essence does not account for their existence.

(If you're familiar with Aristotlean logic you might consider the three acts of the mind: 1. Simple Apprehension, "What is it?" (produces terms - deals with essence), 2. Judging, "Is it?" (produces propositions - deals with existence) 3. Reasoning, "Why is it?" (produces arguments - deals with cause) - essence, grasp of the thing, doesn't get us to its existence or cause, which lays outside it (for creatures anyhow))

As for the second question, I'll return to that when I have a bit more time. I think Plato, others in the classical tradition, and Hegel, have some good reasons for thinking that it is access to the (true) infinite/Good that allows us to become relatively more or less self-determining and free, despite our always being conditioned by our environment. Even Kant's conception of the "good will willing itself" stretches out in this direction, although in a more truncated way. But the short version would be that the transcendence of reason allows the thinking being to go beyond current belief and desire, and it does this by looking for the "truly good," (the target of the "appetite" of Plato's "rational part of the soul").

I will allow though that such a short summary version is probably very unconvincing though. Robert M. Wallace's work on Plato and Hegel is great at articulating the relationship between the Good (Plato) and True Infinite (Hegel) and freedom, so I'll hunt for a good quote. -

Simplest - The minimum possible building blocks of a universeProbably the bit (or qbit), right? 1 or 0, nothing more complex. Presumably, you can say everything about any of the other candidates (except perhaps ideas) with bits.

-

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

Any discrete object is discrete by virtue of standing out against a background. Think of this thesis:

The realm of the senses is all rabbit-duck and it's divided up into discrete-object-background complexes according to the organizing ability of your mind.

Is it possible to disprove this thesis?

No, I think this holds up even from a purely information theoretic view. Floridi addresses this sort of thing in his Philosophy of Information in a chapter on the application of information theory to physics and metaphysics. While we can, in a certain context, speak of the "information carry capacity/'in'" particles of baryonic matter, it is very easy to get mislead here and to start thinking of bits and qbits as building blocks who "contain information in themselves."

Information is always relational though. A proton in a universe where every measurement everywhere has the same value as a proton essentially doesn't exist. You need variance of some sort to have anything meaningfully existing, even in the simplistic toy universe (David Bohm has some good stuff on the priority of difference over similarity, and I think Hegel's ideas on the collapse of "sheer being" into nothing hold up here).

If things are defined by their relations, including their status as constituting even basic ontological difference, then the principle idea underlying substance metaphysics, i.e., "that things properties inhere in their constituents," is simply false. I find this to be a good point in favor of such a view, because I think Jaegwon Kim, and others, have successfully ruled out "strong emergence," under the substance view, and yet we seem to need something like "strong emergence" to explain ourselves.

More controversially, it might be possible to extend this inherit relationality into an argument for an inherit "perspectiveness" to all physical interactions— relevant perspective (or something like it) without experience. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?Rocks also might be the wrong sort of thing to look at for a paradigmatic example of discrete objects. Rocks don't have much of a definite form. A rock broken in half becomes two rocks, generally speaking, and many rocks fused together become one rock, whereas "half a dog" is clearly a half. Rocks are largely bundles of causes external to them. They don't do much to determine themselves.

I would say rather that the paradigmatic example of multiplicity and discrete separation would be the plurality of minds in the world. Further down the chain would be the bodies of animals, which not only have a determinate form but also are relatively self-determining, being what they are because of what they are (and thus having their boundaries contained within them). The dandelion seed clinging to a bears fur is distinguishable from the bear in a way sand laying stop sandstone is not.

This in turn would lead to a view where beings are, as discrete beings, to the extent they have self-determing unity (which is essentially the Thomist view).

Edit: In the classical view, this would often be framed in terms of objects having greater or lesser levels of reality. Ideas have greater reality because they are self-determining in a way, being that they are what makes things what they are. But if ideas and the things instantiating them are mutually self-constituting and subject to evolution, this would seem to challenge the classical view in some ways. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

But it's not a physical thing. It's an idea.

Well, supposing that the world can be adequately described with mathematics, there would be a big difference between the mathematical entities consistent with "triangle" and those consistent with "any being having a first person subjective experience of a triangle or triangularity," right? But the second seems like it would be fantastically more complex, even if it could perhaps be realized in an infinite number of ways.

One of the interesting things about supposing that what underpins conciousness can be described mathematically is that it seems to suppose an entire set of second order entities, "mathematical entities as cognized by some thinker."

And whereas one can locate simple entities seemingly everywhere, overlapping each other in different ensembles, it would seem that the latter sort of entity only shows up in terms of humanity's fathoming of mathematics (at least in our neck of the cosmos). I'm not sure if this is a useful way to think of it, but it perhaps answers the concern about "infinite varieties of forms." For, when it comes to forms that entail cognizing minds, it seems like the actual should have particular precedence over the potential.

The form of "the exact shape of that lump of mud over there," is not even clearly cognized by the person who uses it as an example of the overabundance of forms and ideas, whereas the idea of "triangle" or "dog" is known by almost every toddler. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

This is more in line with the topic. A part is indicated. The question is, is it a part, or is it the 'object' in question? It might be part of something larger, and that larger thing may itself be designated to be part of something even larger, with no obvious end to the game. Hence, the convention is needed. There is no physical way to resolve this without the convention, and the convention isn't physical.

Well, my take here would be that people are physical entities, and cultures are just groups of people, their (physical) artefacts, etc. So their delineations of objects do have physical existence. Granted it is an "incorporeal" (without body) physical existence (i.e., distributed across many brains, books, machines, art work, etc.). This sort of existence, which crosses so many substrates and seems essentially substrate independent, is why I think information theoretic approaches work so well here. "Economic recessions," would be another example of physical phenomena that are "incorporeal" in just this sort of way. The signs used to signify these things are also natural in a way, and their relationship is a natural one.

But there is an important sense in which an information based definition of objects or forms is non-physical, in that it can seemingly be encoded in all sorts of media and also has an abstract, purely mathematical sort of existence in the same way the natural numbers or shapes might.

The sci-fi examples or the Midas Touch I think are unanswerable. There is no one canonical dividing line for entities to refer to when dividing objects. Real world examples here might be instructive. If we want to delineate the boundaries of something for a machine using ultrasound, radar, etc., we might have it calibrated "just-so" as to have returns only come on the sort of thing we want to delineate. So it's an interaction that defines the thing. Another good example might be using a specific sort of solvent so that only the thing you wish to dissolve ends up being washed away. Draino, for instance, is going to interact with hair, soap scum, etc. in a way different from how it interacts with a metal pipe, and this difference essentially delineates between "pipe" and "clog." But if you pick something magical then is seemingly would have no real reason to every stop at one type of thing or another. That said, you could probably still define suspended solid objects in terms of continuous density of matter. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

Well, we do have machines that do this sort of thing, e.g., autonomous spotter drones that can distinguish tanks and IFVs from other objects. Less excitingly, there are license plate readers with can distinguish discrete characters on a moving vehicle.

They work similarly to eyes on a basic level. From the semiotic view, you have signs generated by the interaction between the object and the ambient enviornment, reflected light waves in the examples above, which are in turn picked up by photoreceptors. The similarity starts to fall apart there, since in the animal example there is an experience of the discreteness of the objects, whereas in the machine example there is just a pattern recognition algorithm (although perhaps a dynamic "learning/evolutionary" one).

Both appear to work not by demarcating any discrete boundary for objects in terms of ensembles of fundamental parts (the way modern philosophy has generally thought of this problem) but rather by seeking to identify signs consistent with a given form. For example, license plate readers can handle hand written temporary license plates even though the exact form and material varies from the standard because it is simply looking at an overall level of structure.

The Problem of the Many is, to my mind, a problem that only shows up if we accept the starting presuppositions of a substance metaphysics, where objects properties inhere in their constituent parts—a building block view where "things are what they are made of." On such a view, it's a serious problem that objects can't be identified in terms of discrete ensembles of building blocks.

Process views, which are often inspired by information theory or semiotics, or the marriage of the two (Shannon's model helpfully recreated the Augustine/Piercean semiotic triad) don't have this issue. The demarcation, "if a thing is a cloud" can be defined in terms of some sort of morphism that is substrate independent, which in turn seems to make the issue of "hazy boundaries" less relevant. Boundaries can be hazy because a given morphism might be realizable in very many ways.

Ultimately, I do think Locke's view of "real essences" having to be defined in terms of "mental essences" gets something right here. Without minds, without the plurality of phenomenological horizons, you have a world of complete unity. Cause, energy, and information flow across all "discrete" boundaries as if they didn't truly exist. But mental does not mean arbitrary, and so forms, as they appear in the world, are mutually self-constituting in terms of "mental" and "real" essence (with both only existing apart in abstraction anyhow). Hegel's conception of concepts unfolding in time is perhaps helpful here. When we rethink a concept, e.g. when we learn that "water is H2O," this is a real change in water's physical relations. How a thing is known is not a subordinate, "less real" sort of relationship, but at least as real as anything else (and arguably more real since things most "are what they are," when known.)

The substance view, aside from introducing the problem of superveniance, also has a tendency to make mental relations "less real." Since fundemental building blocks lack intentionality, intentionality must be in a way illusory, or else the sui generis creation of mind. But this separation of mind and nature IMO makes the demarcation problem insoluble. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

Philosophical Investigations, §48

I think this is an area where information theory gives us a very good set of tools for understanding this sort of thing. You can think of a description in terms of maximum lossless compressibility given you want to capture all of the "difference that makes a difference," or the shortest string that can produce that output (Kolmogorov Complexity). When you get to the "real amount of ontological difference out in the physical world," that seems like a question for physics and the philosophy of physics (which is closely related to the question of if the universe is computable). There is an argument to be made that even in the physical science the "differences that make a difference," are context dependent.

The mystery shows up because in abstraction we can posit limitless amounts of difference that makes a difference even in completely uniform media. E.g., you can think of a black square as one black pixel or as 10×100¹⁰⁰ black pixels (Wittgenstein's point about area), but the latter can, in important ways, be shown to be essentially the same thing. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

What constitutes an object is not to be found in physics or in the physical structures around us, but in what we are doing with our language and what we are doing with the objects involved in those activities.

It's more the latter though, right? A human being "raised by wolves" without language would still experience objects, no? Even the sheep recognizes the whole "wolf." Animals by in large react to composite wholes. They often ignore simulacra that only have some elements of the form of the whole they are interested in, which would seem to suggest that action isn't just in relation to undifferentiated streams of "sense data."

The biggest hurdle to this this task is fundamentally you are trying to find object in the absence of language, but you have to use language as an instrument to do it.

It's only a hurdle if you insist on a certain sort of precision or definition. I'd say to that finding objects in the absence of language is incredibly easy, just look around. Spend any time with young children and you'll realize that they have no problem recognizing most wholes even if they have no clue what they are or what they are called. Even at the level of just pointing and asking "what this?" they already differentiate between asking about what the name of some object is and the name of some part of the object. E.g., pointing at an animal figurine to as its name versus pointing just to the horns or tail to ask "no, what is just this (part)." Notably, they can often learn colors before age 2, but good luck getting them to understand grue and bleen. There is a sense in which some distinctions are given.

Another way to think of it is that, were the relationship between our demarcation of objects and the properties of objects themselves completely arbitrary, different cultures should recognize different objects, and learning to demarcate objects according to one's own culture should be a fairly abstract and difficult process. -

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?I would add that these problems become particularly acute, I would say insoluble, if one starts from the position that what we know/experience are "mental representations" or "ideas" rather than these being that through which we know. It's a fundemental difference. The latter view sees the sign in the semiotic triad as joining the object known and the interpretant in a single, irreducible gestalt. The former sees the sign as a barrier between the object and the interpretant. In representationalism, there seems to be no way to overcome the epistemic challenge of explaining how "ideas" relate to things, since all we ever deal in are ideas. Thus, showing how our signs are not arbitrary becomes impossible.

-

Is there any physical basis for what constitutes a 'thing' or 'object'?

So this got me thinking, and I could only conclude that what constitutes an 'object' is entirely a matter of language/convention

Well, suppose you were helping someone fix their plumbing and they asked you to "please bring over that set of pipes."

But then you only see one pipe there, and report this to them. Then they reply: "what? No, that is the set. I consider each 3 inch interval its own discrete pipe."

Well, obviously this would be pretty weird. Likewise, if you look up the rules for the famous "grue and bleen" it's impossible to imagine them ever coming into wide use.

The reason seems obvious enough to me. Language and convention are not themselves "language and convention all the way down." We don't create our distinctions arbitrarily. They do not spring forth from our minds uncaused. As much as human languages differ in categorization, they are more similar than different. For instance, disparate isolated cultures did not come to recognize totally different animal and plant species, with say, large pigs being a different type than small ones. The Sioux long venerated the rare white bison, but they considered this a "bison" despite the variance in color because they categorize animals in largely the same way all peoples do. There is, of course, some variance in edge cases, but on the whole convention seems to correspond to the observable properties of things across different cultures. For instance, I know of no culture that fails to distinguish between plants and animals, opting instead for some other categorization. The same applies for living/non-living.

Certainly, we can imagine that our distinctions and formulations of species and genus could be entirely different. But this is to prioritize potency in our analysis over act. In actuality, they hew towards commonality, and this is presumably not coincidence.

Anyhow, you might be interested in the Problem of the Many, which is closely related: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/problem-of-many/

It deals with the problem of demarcating discrete objects. Some philosophers have tried to get around this by proclaiming that only "fundemental particles" are true wholes, and everything else is just "particles arranged cat-wise, rock-wise, etc." The problem here is that fundemental particles increasingly don't seem so fundemental, having beginnings and ends, as well as only being definable in terms of completely universal fields (i.e., the whole). Physicists and philosophers of physics increasingly want to label them as "abstractions" to stand in for empirical results. I've even seen them called the "shadows on the wall of Plato's cave," in that they lack independent reality and only emerge from a more fundemental reality, and are an abstraction of interactions with that reality.

But, then, giving up on particles and taking this to an extreme, it would seem that we can't really say true things about anything. Ultimately, if all we have is a field of fields, a single unity, everything interacting with everything else, with no truly discrete boundaries, then it seems like nothing can be said because all distinctions would be arbitrary. This is the problem of the One and the Many.

I think the solution is to recognize that:

A. Plurality is obvious and given in plurality of discrete phenomenological horizons (minds) in the world.

B. Our terms and distinctions aren't arbitrary, even if they could conceivably be different. -

Perceived Probability: what are the differences from regular statistical chance?In the poker example, you can think of it purely in terms of frequency. Dice might be even easier though. Suppose we want to know the chances of getting a 7 when rolling two dice.

Well, on the one hand, every roll for each die is independent, and there are 36 possible combinations here, so each would seem to occur with 1/36 probability.

Dice 1 Dice 2 Total

1 1 2

1 2 3

Etc.

But there are many more combinations that total 7 than 2. E.g. 3,4 - 4,3 - 5,2 - 2,5 - etc. (there is an interesting parallel here with low entropy states).

The grouping here depends on what question you want to answer. If the question is: "what are the chances that the first die is a 1 and the second die a 6?" the answer is different from "what are the chances I roll a 7?" With random variables, an outcome will be more common if there are more ways to produce it.

So for instance, Kobe Bryant having died relatively young was a lot more probable than him dying in a helicopter crash because there are many more way for that to occur than for him to specifically die in a helicopter crash.

I'm not sure if it's always a mistake to focus on the seemingly low probability of things happening in a certain way though. For example, even if there are many ways a friend could become a millionaire, I should still be surprised that she became one by winning the lottery. Or even if there were many ways for Tom Brady to win the Superbowl vs Atlanta, we should still be surprised that he could win down 3-28 at the end of the third quarter. -

Do you equate beauty to goodness?I'll go with one of my favorite theories on the relationship between the two, which sees beauty as an irreducible synthesis of goodness and truth. For St. Aquinas, as well as many other classical thinkers, goodness must lie in objects themselves (res), whereas truth is primarily in the mind (anima, soul).

The case for truth lying primarily in the mind is probably the easiest to understand. (1) Things are not true or false in and of themselves, but rather our beliefs or statements about things are true or false. We wouldn't say an oak tree is "true" simpliciter. Rather we might say beliefs about it are true (or false). Truth can't be equivalent with being because there are very many truths about things that are not. For instance, "it is false that gold has 7 protons," is a true statement about what is not.

Goodness being in things is harder to understand from the modern standpoint. The defacto scientific realism of our day would like to say that truth is "out there," whereas beauty and goodness are "subjective," creations of the mind. But they can't be creations of the mind alone, else we would have the mind spontaneously creating these ex nihilo. So, even in the modern account, things have some role to play in our appraisal of their goodness, otherwise such judgements would be arbitrary and impossible to predict. But man's appetites towards different things is far from unpredictable.

For thinkers from Aristotle to St. Aquinas, goodness had to be external to the soul because goodness is what we desire, the aim of appetites (including the intellectual appetites). It is what causes us to act. We always pursue some good in action, even if this is just the unconscious pursuit of homeostasis. Otherwise, our actions would be arbitrary and spring from nothing.

Goodness is the target of practical reason, the judgement of good versus bad. If goodness lay internal to the soul, the soul would have to be self moving, since the whole reason we begin any action is to achieve some good (even if we act unconsciously, e.g. scratching an itch to get relief). But, phenomenologicaly speaking, it seems given that what we desire usually lies outside of us. Experience also tells us that the soul is not entirely self-moving. People do not create themselves, and they are often motivated by extrinsic entities. This is why goodness has to lie, in some important respect, out in things.(2) The key insight here doesn't seem totally at odds with the modern view when examined closely. What motivates us to think things are good has to do with those things; if goodness lay primarily internal to us we would not primarily desire what lies outside of us.

Notably, this does not make the goodness of things rigidly fixed in experience. They clearly aren't. Judgements of appearances can obviously vary, and the goodness of the sensible objects of desire are appearances. Goodness is not unrelated to minds, in the same way that color is not unrelated to minds. However, the primary locus of goodness and color is things. We might say that they exist in virtual form (intentions in the media) in things. The sign that we interpret as red, good, etc. comes from the thing, where as truth applies to beliefs—propositions—which are essentially intellectual entities.

Now, goodness, truth, and beauty are considered "transcedentals." They are transcedentals because everything can be said to have them, but they are not covered by any of Aristotle's categories, which otherwise seem to define things. That is, the truth, goodness, and beauty of a thing, does not reduce to its substance (what it is, e.g., horse, rock, etc.), where it is, when it is, how it is positioned, etc. Goodness, truth, and beauty "transcend" these categories. For instance, it is really easy to see how truth applies to all categories. We can make true statements about any thing vis-á-vis all the categories (e.g. it is true that Spot is a dog, is on the floor, is laying down, etc.).

So how do beauty and goodness relate? Consider the classical formulation of beauty as: “that which, when