-

Idealism in Context

Well, that's a thorny area in Kant scholarship, right? I have read many contradictory takes on the exact relation (or "negative" or "limiting" relation) between appearances and things-in-themseleves. Because Kant also makes it clear that appearances are of things, and is cognizant of the fact that if appearances bear absolutely no relationship to what they are appearances of, they would simply be free standing, sui generis entities (e.g. in the Transcendental Aesthetic). Although I know there are also more "subjective idealist" readings of Kant.

The things that we intuit are not in themselves what we intuit them as being [yet they are the "things we intuitive"]. Nor do their relations in themselves have the character that they appear to us as having. And if we annul ourselves as subject, or even annul only the subjective character of the senses generally, then this entire character of objects and all their relations in space and time-indeed, even space and time themselves would vanish; being appearances, they cannot exist in-themselves, but can exist only in us. What may be the case regarding objects in themselves and apart from all this receptivity of our sensibility remains to us entirely unknown. All we know is the way in which we perceive them.

A-42/B-59 (emphasis mine)

Also in the section you quoted:

hence what is in them (appearances) are not something in itself, but mere representations, which if they are not given in us (in perception) are encountered nowhere at all.

But representations are still representation, not sui generis free standing actualities with absolutely no relation to what is being represented.

In the section after the one your referred to:

The non-sensible cause of these representations is entirely unknown to us, and therefore we cannot intuit it as an object; for such an object would have to be represented neither in space nor in time (as mere conditions of our sensible representation), without which conditions we cannot think any intuition. Meanwhile we can call the merely intelligible cause of appearances in general the transcendental object,' merely so that we may have something corresponding to sensibility as a receptivity.

(Emphasis mine)

What is meant by "unknown" exactly seems to be the cause of some controversy. Kant is obviously speaking about them at least. Obviously, this is not "cause" as in the categories, because he denies this in prior sections. In English I have seen "affectations" used as a placeholder word here so as to not confuse it with empirical causes. But I think the Scholastic objection would probably rest here on the generally deflated sense of causes as well.

Anyhow, by "action," (a poor word choice perhaps) I think it is clear that Clarke doesn't mean the knowable causal relation, or else he would have no qualms with Kant because Kant would merely be following the old Scholastic dictum that "everything is received in the manner of the receiver," and the old Aristotleian view that sensation is of interaction. But the Neoscholastic opposition to Kant is generally that he absolutizes and totalizes this old dictum.

Anyhow, what translation are you using? And is that the First Critique? I couldn't find that line. The closest rendering in that section I could find is in here:

in themselves, appearances, as mere representations, are real only in perception, which in fact is nothing but the reality of an empirical representation, i.e., appearance. To call an appearance a real thing prior to perception means either that in the continuation of experience we must encounter such a perception, or it has no meaning at all. For that it should exist in itself without relation to our senses and possible experience, could of course be said if we were talking about a thing in itself. But what we are talking about is merely an appearance in space and time, neither of which is a determination of things in themselves, but only of our sensibility; hence what is in them (appearances) are not something in itself, but mere representations, which if they are not given in us (in perception) are encountered nowhere at all.

These are the Cambridge one. -

Idealism in Context

The other thread reminded me of another contributor here. There was also an explosion in logical work in the late middle ages. Partly, this is because the univocity of being allows logic to "do more" because there is not this supposition that in the context proper to metaphysics we are generally speaking of analogy (in the one being realized analogously in the many, or "analogous agents" causation). Nominalism also does some things to make it seem like logic is more central. No longer can natures explain divine action. God can "make a dog to be a frog" rather than "replacing a dog with a frog" or some sort of accidental change ("making a dog look like a frog"). Wholly (logically) formal contradiction becomes the limits of possibility. This is also when the embryo of possible worlds with Buridan starts, rather than modality being defined in terms of potentiality.

All this makes logic more central, and then logical solutions come to drive metaphysics. So, Ockham has the idea that problems with identity substitution related to the context of belief can be resolved by claiming that references in belief statements suppose for the believer's "mental concept" or a thing rather than the thing simpliciter (restriction). But this neat logical move is then taken as prescriptive for metaphysics and epistemology, and you get "logic says we only ever know our own mental concepts," (representationalism).

This is all compounded by the context of the Reformation and Counter Reformation, because the focus on logic to adjudicate arguments becomes even more intense.

Guys like Pasnau and Klima put it this way, logic comes to colonize metaphysics.

You can also see this in the primary/secondary properties distinction. Originally, it is quantity, magnitude, i.e., the common sensibles, which are secondary. And they are merely "secondary" in terms of not being the primary formal object of any one sense. But this gets flipped, so that mathematics (obviously univocal in this context) becomes primary, and the secondary also becomes in a sense illusory, a sort of projection. -

The Old Testament Evil

Off the top of my head, this seems to hold for Ezra or Maccabees. I have seen this trend remarked upon as well. God goes from being a direct parent figure (a "helicopter parent") who speaks to individuals, to speaking through prophets to a corporate people, to (in the Christian Scriptures) speaking to man as man, to a direct indwelling of the Holy Spirit and the putting on of the "Mind of Christ." This can be put in developmental terms, i.e., as man moves from "childhood towards adulthood," we see the need for the internalization of external teaching, with the teaching becoming more and more hands-off as man matures (and man is allowed to fail more often and more severely). It can also be put in terms of an "exitus et reditus," a fall from the presence of the divine, and a parallel ascent and return.

Anyhow, in support of such a reading of Samuel, Samuel doesn't seem particularly concerned with being a strict documentary (if it was, we shouldn't expect ambiguity). In I Samuel 16 we get the first David origin story, with David being selected to play the lyre to calm Saul who is afflicted by an evil spirit. In I Samuel 17, we get the parallel story of David killing Goliath. But in I Samuel 17, we Saul and Abner seem to have no idea who David is, whereas, in I Samuel 16 he has already become Saul's beloved armor bearer who goes everywhere with him. Some commentators have tried to explain the disconnect as amnesia brought on by the evil spirit (and Abner is just humoring Saul), but this seems like a stretch. Or we could assume that Samuel 17 comes first, but then we have the same sort of problem where Saul should know David.

Often this is explained as two parallel takes on David, where by Biblical convention a character's first words and appearance define them. In this first, God is central, and David is a sort of conduit, whereas in the second, God is absent and David is a worldly military leader. We get the two sides of David.

In terms of the text giving guidance itself, such a disconnect (if one takes the point of the text as being primarily documentary) could hardly have been lost on the writer or any redactor. It's like that for a reason. There are a number of cases like this in the Bible, right from Genesis 1 vs Genesis 2. And I think this at least suggests a close reading.

But how is it inerrant if the author's are untrustworthy and give false information?

It wouldn't be false in that reading, it simply reports what Samuel says. But see the point above about the parallel David introduction stories. One can take the text as divinely inspired and not take its purpose as being primarily a straight documentary. If it was, it is, at the very least, quite confused. -

The Christian narrative

That's an interesting thought.

Relation is one of the categories in the Categories though. It isn't a "thing." That would be substance. This is quite explicit. The logic was developed with the metaphysics in view.

However, what you have described might be responsible for the later calcification of essences. I've seen that thesis expressed before. But one doesn't find such a reification in the Patristics or early-high Scholastics. Everything exists in a "web of relations" as Deely puts it. It's a very relation heavy ontology. The calcification and reification is more of a post-nominalism thing. Commentators have supposed that it has something to do with the limitations of logic at that point, but this is also combined with a particular (new) view of what logic is/does and a particular metaphysics of univocity. Whereas, in the earlier metaphysics, metaphysics always deals in analogy.

I think this would be more a question about universals in general though. -

Idealism in Context

So what I'm arguing is that it wasn't Kant who 'blew up the bridge', but the developments in the early modern period to which Kant was responding.

That's probably a more fair genealogical take. Clarke isn't really clear on which "version of Kant" he is referring to, and there are many. The reference is not followed up on in detail.

Most of the genealogies I've read, like Brad Gregory's The Unintended Reformation, D.C. Schindler's work, John Milbank's work, Amos Funkenstein's Theology and the Scientific Imagination from the Middle Ages to the Seventeenth Century all place the shift in the late middle ages, with Scotus and Ockham being the big figures, but also some German fideists who I can't recall the names of, as well as a somewhat gnostic strain in some forms of Franciscian spirituality. And the initial shifts are almost wholly theologically motivated, as opposed to relating to science or epistemology. The Reformation really poured gas on the process. The "New Science" comes later in a context that is already radically altered.

I've said before that Berkeley strikes me as a sort of damaged, fun house mirror scholasticism in a way. The analogy I would use is this. A big cathedral had collapsed. People had started building with the wreckage. They built their new foundation out of badly mangled and structurally impaired crossbeams from the old structure (e.g. "substance" and "matter"). Berkeley is pointing out to them that the materials they are using are badly damaged, but he also doesn't seem totally sure what they originally looked like before the collapse. (Now, a question of considerable controversy in this analogy is whether the cathedral collapsed because it was poorly built or because radical fundementalists dynamited it).

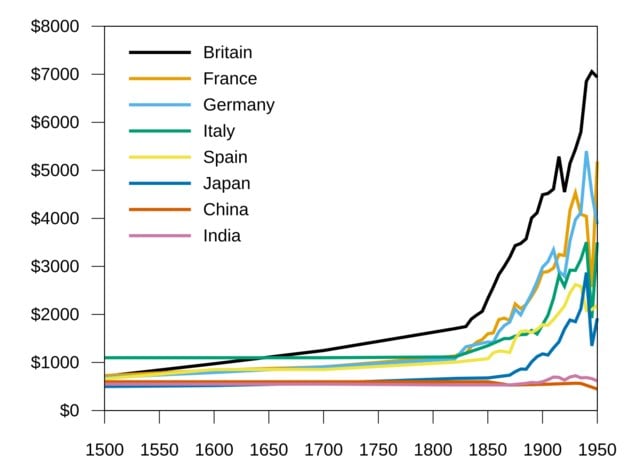

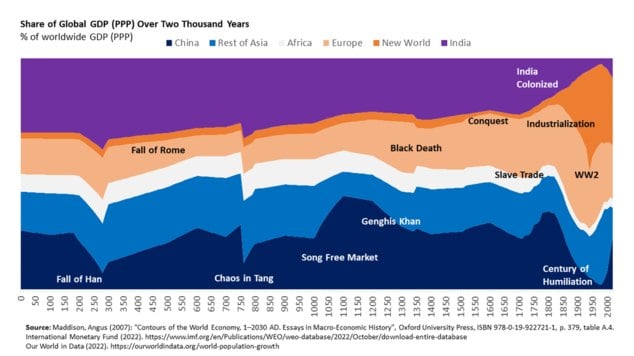

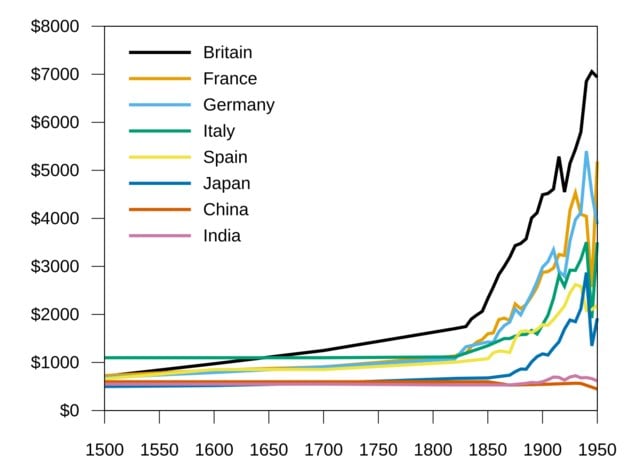

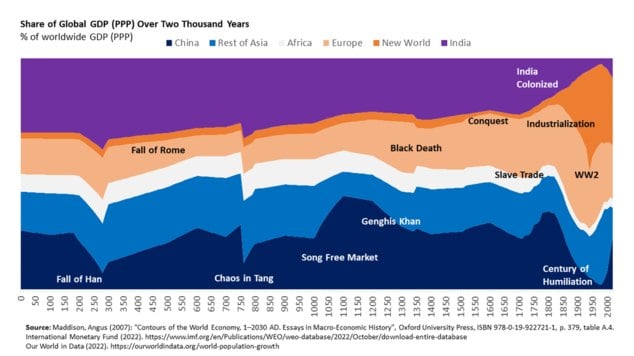

On a side note: I've also seen the argument that we are today largely the inheritors of a sort of "whig history" of science, that tells a story about how changes in philosophy (primarily metaphysics and epistemology, but also ethics) are responsible for the explosion in technological and economic growth that took place during the "Great Divergence," where Europe pulled rapidly ahead of China and India. A key argument for materialism is "that it works," and that it "gave us our technology." But arguably it might have retarded some advances. Some pretty important theories were originally attacked on philosophical grounds related to mechanism for instance.

Also, the timing is off. What you have is a fairly stable trend before and after the new science diffuses and then an explosion in growth with industrialization. The explosive growth actually coincides with the dominance of idealism, the sort of high water mark following Kant and Hegel. But I think it's probably fairer to say that the type of iterative experimentation driven development of industrialization was not that dependent on metaphysics. But this is relevant inasmuch materialism is still today (although less so) justified in terms of it being synonymous with science. -

The Christian narrative

Given your affinity for neoplatonism, I'm quite surprised it doesn't at least make some sort of sense. In its broadest sense, the general idea is quite flexible. -

Referential opacityAnyhow, for another topic of conversation related to my confusing example: we might question whether we can really avoid a solution more like Ockham's so easily. Can opacity vis-á-vis belief wholly semantic and logical?

Consider a book, rather than a believer. A book says something like: "Superman can fly" or "Mark Twain is a best seller." Does the book also say that Clark Kent can fly and that Samuel Clemens is a best seller? Does identity substitution work here? Now, on one view, we could ask what the writer intended. If the writer intended to express their beliefs and has no idea that Mark Twain = Samuel Clemens, and the text is taken as an expression of belief, then it seems that we cannot substitute? Whereas, on a "death of the author view" it would seem to be the reader who determines in substitution holds in ambiguous situations.

But, if we want to keep to a view where opacity is purely a function of language/contexts itself, what of ambiguous statements in the context of something like an anonymous text, a p-zombie, random text generator, or AI? -

Referential opacity

I just brought that one up because it is an example that seems like obvious equivocation that is not actually equivocation (or false) depending on how the first premise is meant (the first premise can also be true or false depending on how it is meant). And my thoughts were that the same might be true for a person / persona distinction.

But, it's also the case that if "ice is water (any phase)" is meant as identity, but then "water (makes for a good bridge," is meant as "liquid water makes for a good bridge" then we have a fallacy of four terms, having introduced "liquid water" for the very first time in the conclusion.

So, there is a valid and true version, an undistributed middle, or four terms. The way you switch between them despite an identical natural language rendering could be described under supposition theory. Supposition theory was also used for referential opacity in the past. That's how Ockham covers belief, in belief statements the term for the object supposes for the knower's mental conception of the known (an unfortunate move that contributed to representationalism). There are similar moves around modality with the idea that terms suppose differently (are ampilated by the modal context).

I thought of it because Ockham's solution is similar to Quine's in some ways, but works using a theory that explains some types of "equivocation." So, there is a sort of similarity. -

Referential opacity

The ice bridge argument is just invalid. It's another undistributed middle.

(i = w) ∧ Bridge(I) ⊢ Bridge(w)

Is not an undistributed middle. -

The Christian narrative

Yes, exactly. :up: So if we say an essence is a definition, it'd be a bit like saying New York City is the name "New York City," or that smoke, as a sign of fire, is fire. -

Referential opacity

I said they were different. My point is that those sorts of equivocations look similar in natural language, and involve only nomological contexts, but still involve shifting between contexts.

As and were discussing, we also might make a distinction between personae and persons. This happens whenever actors are referred to by their real names to describe events in movies they act in for example. This seems context dependent too. -

The Christian narrative

The way St. Thomas puts it in De Ente et Essentia, which is fairly standard, is that essences are the metaphysical reality, and definitions are the signification of that reality (the signification of the quiddity). A "nature" by contrast, is the same idea as respects change and motion (interaction), it's the essence as a principle of action.

Now in the classical metaphysical tradition (Pagan, Jewish, Islamic, and Christian) there is no distinction between primary and secondary qualities à la Galileo, Locke, etc., and so the phenomenological "whatness" of things is included in this picture. The phenomenon of understanding is considered to be the primary datum of epistemology. -

The Christian narrative

Think about it this way. Prior to my writing this post, it only existed potentially. That it has become actual shows that it existed potentially. My post had to become actual before you could read it. Its moving from potency to act, i.e. actually being written and posted, is prior to and causally related to your act of reading it (which is also a move from potency to actuality).

So too for essences. Different kinds of things interact in different ways, which has to do with what they are (their form/actuality).

But the basic point doesn't require this terminology. It's simply the point that some actuality must preceed and determine any move from potency to actuality. If it didn't, and things/events could spontaneously move from potency to actuality, they would occur "for no reason at all." That is, they would be wholly uncaused.

Different things interact in different but reliable ways. The idea of substantial form is really just the idea that there must be something that causes such interaction to be one way and not any other.

The quote from Norris Clarke here lays this out in terms of epistemology. -

The Christian narrative

The take away is that DNA does not divide the world up neatly in to species.

:up:

But that's sort of the point. Again, although you represented "a spreadsheet lookup array" metaphysics as my position, I actually presented that as a deeply flawed conception of essences. Unifying principles are realized analogously in the many. The idea of a sort of univocal, mathematical lookup variable for essences is critically flawed. This isn't how the term was originally used, but is rather a product of late medieval nominalism and its demand for total univocity.

The question isn't: "how exactly do we categorize species?" or again "how do words signify species?" but rather, how are there species? English, for instance, is full of unique words that specify domestic animals by sex and age, or by having been castrated. The exact classification scheme isn't the point. That there are species does not require a "lookup array." The negation of the position is not "but species cannot be defined as static, logical entities (as in a computer database)" but rather "there is not any actuality that is responsible for different species being different species." Or, something like: "there are no different species and genus simpliciter, but only things called such," which also suggests "there are no things, no organic wholes, but only things called such." -

The Christian narrative

I would think not. A stray hair has your dog's DNA. A severed cat tail or paw has cat DNA. In theory, you could take a cat embryo and tweak its environment so as to make it develop into nothing but muscle tissue or nothing but liver tissue. But a stray hair is not a cat, not is meat a chicken, or a severed tail a monkey. Likewise, the form of a cat can be, to some degree, present in a statue or photograph.

I think information theory and complexity studies is perhaps the better lens to think of essences in terms of physics. They would be informational structures/morphisms. Although, whether or not what things are is reducible to information is questionable. There are a lot of open problems in the philosophy of information that are relevant to this. I would lean towards saying that such principles are realized analogically. The idea of essence/form is very broad, it's just the idea of a prior actuality that stands in relation to interaction. -

The Christian narrative

The concept cat wouldn't exist do to there not being a language, but the fact (the state of affairs in which cats exist) would still obtain. In other words, facts would still exist without the concepts that refer to them. Modal logic does apply. Modal logic deals with possibility and necessity, and you're positing a possible world without humans, if I'm following you correctly.

Facts are facts in virtue of modal logic? The question here is metaphysical, what makes things what they are. No doubt, modal logic can be used descriptively—as you say—but I am not sure about modal logic as an explanation of why anything is any thing at all. Or "anything is anything at all because of modal logic.

That is:

"Why are cats the specific sort of organic wholes they are?"

"Because modal logic allows us to stipulate x exists and x is a cat."

This is still an explanation that posits that logic or human speech is constitutive of what things are, that things are what they are in virtue of us saying so.

By contrast, a truth maker theory would say that states of affairs/facts obtain in virtue of actualities that are not posterior to human logic or speech. -

The Christian narrative

He even humorously suggested that Aristotle deserved a Nobel Prize in biology for this insight (however Nobel prizes are never awarded posthumously, much less to someone who died more than two millenia ago.)

As a consolation, he and Darwin remain the most cited people in the field IIRC (although often in a pretty cursory fashion to be fair). Although, arguably this is old news by Aristotle's day and he is just formalizing it. The earlier parts of Genesis, which pre-date the Hebrew language, and some of which go back at least to almost 4,000 year old tablets, have to notion of "each according to its kind," arising from seed according to its kind, with an animating life force of sorts that disspates back into the "dust" of no longer ordered matter. I don't recall Homer focusing on animal life in quite the same way though (although he does have canine virtue in old Argos!).

On a related note, I have often considered that the ancients, who spent considerable time with animals, often sleeping with them, using them for all forms of work and transportation, and traversing wilds that were actually still wilds instead of depopulated reeling ecosystems, might make better psychologists vis-á-vis the man/brute distinction than many moderns who are writing from a perspective of maybe having owned a pet.

Delbrück highlighted that it's the formal aspect of DNA, the information it carries, rather than the physical material of DNA itself, that is crucial for inheritance and development. This aligns with Aristotle's view that the soul (form) is distinct from the physical body. Also, presumably, one of the reasons that Aristotle's hylomorphism is still very much a live option in contemporary philosophy.

Indeed, but we could also consider here epigenetics and developmental biology, or the possibility of non-DNA life, or self-replicating non-living systems such a silicone crystals. The idea of an essence and substantial form is the more general one here, which is partly what makes it more useful. It isn't pinned down to any particular material. So, in the case of xenobiology, were there different forms of life discovered on Mars or the Jovian moons that were close to "bacteria" but also distinct in chemical composition, it is the broader notion that would help capture the similarity (principles unifying the disparate "many" into a knowable "one"). Information theory is a pretty popular way of doing this now, and the etymology is not incidental, "information" being what "in-forms."

Yet information is sometimes presented in a way that tends towards reductionism, although it need not be. It seems to me that hardcore mechanists realize this best, and this is why they still largely deny the existence of biological information as anything but a useful fiction, mere mechanism as seen through the lens of the illusion of function.

What has this to do with essence? It's that the same philosophical heritage that gave rise to 'essence' and 'substance', also gave rise to the scientific disciplines that discovered DNA. And I don't think this is coincidental.

Right, Schrodinger's (a big Platonist fan) landmark "What Is Life?" which was the first to clearly posit something like DNA to look for builds on these notions. -

The Christian narrative

You could have just reached for "domesticated animal" or "livestock." But no, I was clearly asking for a culture that doesn't distinguish the species at all. Find one and I would be shocked.

There are also slightly different words for colors across different cultures. And yet not a single one has a unique name for colors in the ultraviolet spectrum. Why? I think it's easy to chalk this up to causes that are prior to usefulness. Such differentiations are not useful because of what man is and which colors he is able to distinguish with the naked eye. Color schemes are also remarkably similar, despite lacking the more clear distinction of species.

I'm not arguing against the formalism, but the claim that cats are cats in virtue of someone being able to write down "x exists and x is a cat."

To see how it works, you have to do the work.

So everyone who truly understands modal logic believes that things are what they are in virtue of our ability to write that it is so? I suppose very few people properly understand it then.

In response to: "Ok, then explain in virtue of what would [cats] be cats in this case [where there is no one to declare them cats]?" You wrote:

In virtue of the supposition of a world that includes cats but not people.

That's how modality works. We can stipulate a possible world in which there are cats but no people to call them cats

You don't need modal logic for this sort of metaphysics. You can just put it plainly: "cats are cats because I stipulate that it is so. They would still be cats even if I didn't stipulate this however, and this simply because I can say 'I stipulate that this is so regardless of whether or not I have actually stipulated it."' The appeal to logic just dresses up the reliance on assertion to make anything any thing. -

Referential opacity

Stop equivocating

That's the whole point of the example though?

"Water" can mean the liquid only, or it can mean any of liquid, solid, and gas. If we assert that water = H₂O, we are asserting the latter, since we are also by symmetry asserting that H₂O = water.

Dude, H₂O≠ liquid water. -

The Christian narrative

In virtue of the supposition of a world that includes cats but not people.

So cats would still be cats in a world without people in virtue of the fact that people have created a logical system that allows them to say "cats would still be cats in a world without people?" And I suppose that trees were trees before there were people in virtue of the fact that people can make the claim "there were trees before people?"

If you are not going to study modal logic, I guess you will have to take my word for it.

Use of modal logic has nothing to do with your explicitly metaphysical claim that cats are cats in virtue of the fact that modal logic allows us to say that cats are cats in a world without people. We could also have the supposition that cats would not be cats in a world without people, so I have no idea what this is supposed to show. If things are what they are simply in virtue of our ability to simply state that they are so this would seem to lead to a sort of Protagorean relativism.

Indeed, it looks like the supposition is doing all the lifting here and modal logic has nothing to do with it. "Cats are cats in virtue of the fact that we say they are cats, and they would be cats even if we didn't exist to say this in virtue of the fact that we say that they would still be cats even if we hadn't said so." I am not sure if this is contradictory or not.

Can you see why I call this extreme volanturism?

Anyhow, for someone who says they logic is just a tool, and that any logic can be used just in case we find it useful, you sure do like to appeal to formalisms quite a bit to make metaphysical claims.

It shows again that we do not need a theory of essences in order to use words.

It might well be the core of our differences. I take effective language use as granted - it's foundational that we are talking here about cats and essences and possible worlds. If that is not granted, then our talk would indeed be incongruous scratchings. You, in opposition, seem to hold that we could only have this successful practice against a complicated Aristotelian or Platonic theoretical base.

But babies do talk, and the do not understand Aristotle.

The performative contradiction is in your already using language in order to formulate the very theory you think you need in order to use language.

Essences are not primarily called upon to explain common terms. I have pointed this error out before. -

Referential opacity

That's because of how you are translating it. If the relation is identity then it is:

(i = w) ∧ Bridge(I) ⊢ Bridge(w)

"Water" can mean the liquid only, or it can mean any of liquid, solid, and gas. If we assert that water = H₂O, we are asserting the latter, since we are also by symmetry asserting that H₂O = water. I don't see an issue, provided we are clear here. Tim's post seems tangential.

That was exactly my point. And on the view that ice is water, water can indeed be made into a good bridge/ice road given the right conditions.

The reason I thought of it is because you can construct a parallel with proper nouns that share a name in some contexts and not others, which results in similar looking "errors."So for instance, "Palaestina" was a Roman renaming of the same exact provinence following their explosion of the Jews, and the general geographic area is referred to as either "Israel" or "Palestine," whereas the modern political entities are clearly different.

If you allow for a distinction between personae and persons, you get something quite similar. For instance, Stone Cold Steve Austin loves beer. That's part of the character. In theory, the actor might not. -

The Christian narrative

Well, what do you think of the notion of principles outlined above? And could there be a principle by which different individuals are the same sort of thing?

Do you also think there are no natural kinds? Or are there at least some, like the photon, electron, iron atoms, helium, etc.? Do things have accidental and essential properties, or are all properties accidental (or essential)?

The key idea of a nature, physis, is precisely that things are always changing and that there is no strict, univocal measure of the sort you are speaking against. In later refinements of the idea there is also the realization that things are defined in terms of their contexts. For instance:

For all created things are defined, in their essence and in their way of developing, by their own logoi and by the logoi of the beings that provide their external context. Through these logoi they find their defining limits.

-St. Maximus the Confessor - Ambiguum 7

I'm afraid the rest doesn't give me much to go on. What exactly is the notion that is antiquated? To 's point, "Sigh. Attempting to throw the ball back to you." That isn't it. The term "essence" has been used in very different ways throughout the history of philosophy. Locke's real/nominal essences are very different from what Hegel has in mind and both are very different from what modern analytics have in mind, with their "sets of properties"/bundle theories, which is wholly at odds with how the Islamic and Scholastic thinkers thought of essences. So I am just trying to disambiguate.

My first thought on your first response was that it didn't seem to contradict the idea of essence I laid out last page, and that's sort of how I feel about this one. Unless the idea is simply that "metaphysics" is antiquated as a whole, and that this is why "science" answers questions about essences?

Well, there has to be some thread of invariance running through any coherent process. Linear algebra's change of basis theorems and basis-independent operators are a good window into this. Invariance under transformation is essential for deep learning and other machine learning models' ability to generalize. What allows for this is that the same underlying relations endure despite shifting representations. Were there no conserved structures or consistent symmetries it's hard to see how any learning would be possible.

Of course there would be cats. Just no one to call them "cats" -

Ok, then explain in virtue of what they would be cats in this case?

Obvious as this is, I am pleased that at least you have understood this.

I think we may be equivocating on "exists." If to exist is something like "to be the value of a bound variable," it should be obvious that this is not what I have in mind, or what is commonly meant by the term.

Babies use words despite not understanding Aristotle

Is this inane strawman more "performance art?" -

The Christian narrative

Right, this is the extreme volanturism and linguistic idealism I was talking about. Cats would not exist if man was not there to call them forth as such.

But my point would be that disparate cultures all came up with names for species, and the notion of species, because those things exist. That is, simply appealing to use is a not an answer. There are causes for what appears to be useful. The fact that biological species exist (prior to man and his language) is the cause of such categorizations being useful in the first place.

You've tried this argument before. The term "cat" is indeed in a sense arbitrary. We could have used any word we like, we could have not had a word for cats, or had one word for both cats and dogs, or any of innumerable other combinations. That we happen to have the word "cat" is not ordained by God, but an accident of the history of English.

First, name one culture that conflates cats and dogs, or any other domesticated animal.

Such categorizations are not arbitrary. If you try to mate cats to dogs you don't get offspring. If you try to get cats to help shepherd your flocks it will be an exercise in futility. You cannot lash cats to a sled to pull yourself around, etc. What people find to be useful has causes that are prior to any human consideration of usefulness. The entire example of a civilization that is "just as technologically advanced as ours," but doesn't understand the periodic table is absurd. They could obviously categorize things in many different ways. But categorizations that allow for modern technology will necessarily be isomorphic to one another.

As I put it before, I reject the idea that:

"In the beginning the Language Community created the heaven and the earth. The earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the soup of usefulness. And the Spirit of the Language Community moved upon the face of the waters. And the Language Community said, Let this be light: and thus it was light." -

The Christian narrative

What exactly is the difference between a property and an ability? Or is it just that minded things have abilities instead of properties for whatever "properties" relate to their mindedness? Or are abilities volitional? For example, is the ability to feel pain or get angry and ability? Or is it more like the ability to choose to walk across a room?

Sorry, I am not familiar with this distinction. -

The Christian narrative

You'll have to lay out what you understand by "essence" because I'm not sure how these objections apply to what I've said or realist uses of the term more generally. In its most basic terms, the rejection of essences would be something like: "there is nothing in virtue of which all cats are cats."

The essences might be "emergent" is a pretty common position among those philosophers who hold to a position that requires emergence (process philosophy normally denies that it needs any such notion).

Essences are principles, so they are by definition, general. They are a unifying one by which a many are known. To wit:

The epistemic issues raised by multiplicity and ceaseless change are addressed by Aristotle’s distinction between principles and causes. Aristotle presents this distinction early in the Physics through a criticism of Anaxagoras.1 Anaxagoras posits an infinite number of principles at work in the world. Were Anaxagoras correct, discursive knowledge would be impossible. For instance, if we wanted to know “how bows work,” we would have to come to know each individual instance of a bow shooting an arrow, since there would be no unifying principle through which all bows work. Yet we cannot come to know an infinite multitude in a finite time.2

However, an infinite (or practically infinite) number of causes does not preclude meaningful knowledge if we allow that many causes might be known through a single principle (a One), which manifests at many times and in many places (the Many). Further, such principles do seem to be knowable. For instance, the principle of lift allows us to explain many instances of flight, both as respects animals and flying machines. Moreover, a single unifying principle might be relevant to many distinct sciences, just as the principle of lift informs both our understanding of flying organisms (biology) and flying machines (engineering).

For Aristotle, what are “better known to us” are the concrete particulars experienced directly by the senses. By contrast, what are “better known in themselves” are the more general principles at work in the world.3,i Since every effect is a sign of its causes, we can move from the unmanageable multiplicity of concrete particulars to a deeper understanding of the world.ii

For instance, individual insects are what are best known to us. In most parts of the world, we can directly experience vast multitudes of them simply by stepping outside our homes. However, there are 200 million insects for each human on the planet, and perhaps 30 million insect species.4 If knowledge could only be acquired through the experience of particulars, it seems that we could only ever come to know an infinitesimally small amount of what there is to know about insects. However, the entomologist is able to understand much about insects because they understand the principles that are unequally realized in individual species and particular members of those species.iii

Some principles are more general than others. For example, one of the most consequential paradigm shifts across the sciences in the past fifty years has been the broad application of the methods of information theory, complexity studies, and cybernetics to a wide array of sciences. This has allowed scientists to explain disparate phenomena across the natural and social sciences using the same principles. For instance, the same principles can be used to explain both how heart cells synchronize and why Asian fireflies blink in unison.1 The same is true for how the body’s production of lymphocytes (a white blood cell) takes advantage of the same goal-direct “parallel terraced scan” technique developed independently by computer programmers and used by ants in foraging.2

Notably, such unifications are not reductions. Clearly, firefly behavior is not reducible to heart cell behavior or vice versa. Indeed, such unifications tend to be “top-down” explanations, focusing on similarities between systems taken as wholes, as opposed to “bottom-up” explanations that attempts to explain wholes in terms of their parts.i... -

The Paradox of Freedom in Social Physics

Right, if you offer 10,000 people either a rotting, stinking fish to eat, or a choice of appetizing meals, and no one chooses the rotting fish, this does not demonstrate a lack of freedom. That no one wakes up one day and decides to slap their hand on a hot stove doesn't show a sort of tyranny of our appetites over free action.

This is why I like the classical definition of freedom as: "the self-determining capacity to actualize and communicate goodness." A benefit here is that this definition works with libertarianism, compatible, and fatalism.

It's our ability to do what is best that determines freedom. Whenever someone chooses the worse over the better, it is presumably because of ignorance about what is truly best, weakness of will, or external constraint or coercion. But all of these represent a limit on freedom. To use an example I like, even Milton's Satan must say "evil be thou my good." To say "evil be thou evil for me" and then to choose evil is insanity. This goes along with Saint Augustine's point that the soul being unable to turn away from the beatific vision in Heaven is not a limit on freedom for the same reason that an inability to trip and fall is not a limit on our freedom to walk, or an inability to crash one's ship is not a limit on our ability to pilot.

So to me, the question is not whether a well-ordered society having good incentive structures robs us of freedom, it is rather the degree to which our having poorly structured incentives does so. That is, knowledge of economics and psychology can be used wisely or poorly, to promote virtue or vice, to help man become free or to frustrate his freedom.

There is no platonic, perfectly ratoinal, self-interested individual that is free to decide merely according to his/her own will.

Right, and in the Platonic tradition the Good is determinate of wise, free action, not a sort of sheer volanturist will. Man's end, his happiness, is related to what man is, his telos. Nonetheless, the tradition normally maintains that all rational beings have their end in freedom and knowledge of/union with the Good. -

The Christian narrative

As if there never need be a table to use “table”.

Right, and theories of essences and universals are not primarily about naming and referring. The idea of use fixing the meaning of stipulated signs is in realists, such as Saint Augustine, John of St. Thomas, etc. The analogy between languages and games doesn't preclude realism either, provided it isn't stretched too far into positing a sort of sheer formalism.

Essence is intimately connected to language, and intelligibility, but it is not wholly subsumed by language and more rightly sits in things, as “what is known and said about them.”

Right, in general what is more directly relevant is metaphysics and physics, or the basic intelligibility by which arbitrary terms can even be coherently formed via composing, concatenation, and division. Final causality is probably the most relevant issue, not signification. -

The Paradox of Freedom in Social Physics

It's an interesting question. The idea of "nudges and incentives" still dominates the public policy space. If you look back, you can see that people were long aware of the ways in which the social and economic environment shapes preferences and actions. Herodotus makes an argument for a pretty expansive cultural relativism for example, and Plato's ideal communities in the Republic and Laws presuppose a great deal of malleability.

A basic idea that emerges is that laws and customs should ideally shape people towards virtue and a sort of internal balance, with virtue being a state in which "people desire to do what is best," rather than simply being able to force themselves to comply with norms or ideas about what is best. This is explicit in Aquinas for instance, who sees human laws as having a positive educative function.

But, the idea here is actually that this nudging and education, a sort of self-cultivation, is actually a prerequisite for liberty, the idea being that self-governance is not easy to attain. On this view, people don't become self-determining and self-governing by default when they become adults. To become relatively more self-determining is rather an arduous process. Someone ruled over by untamed passions or ignorance is, in an important sense, unfree. They are simply following desires they have not chosen. In Harry Frankfurt's terms, second order volition are key, the effective desire to have or not have certain desires (presumably because one knows such desires as truly worthy or not, a function of the intellectual appetites).

That's sort of the original idea of the "liberal arts." They are liberal because they help man to become more free. Patrick Deneen is a good modern commentator on this tradition.

Obviously, unvirtuous states can also create laws and norms that lead to unvirtuous citizens. That's one problem here. Homer is a fine example. The Iliad is an example of an obsession with thymos and purely martial virtue that leads towards a sort of self-destructive and pointless drive to conflict, one which Homer recognizes even if his heros don't.

But, the ideal, at least in its broad outlines, makes a certain sort of sense. Self-governance at the individual and collective level requires cultivation. As Saint Augustine says in The City of God, "the wicked man, though a king, is still a slave, and what is worse, he is ruled over by as many masters as he has vices."

Modern political economy tends to loose sight of this vision. In part, this is because the normative is divorced from the positive, and yet the positive still gets used to make normative claims (e.g. efficiency as a proxy for choice-worthy).

Yet I think the problem tends to lie more in the anthropology of political-economy/liberalism, which tends to be quite flat, reducing man to homo oecononimicus, the atomized utility maximizing (or satisfying) agent, whose actions are guided by the "black box" of utility, which flattens all the appetites into a single univocal measure. Francis Fukuyama represents an improvement here, in that he recognizes the particularity of thymos (the appetites for honor, respect, recognition, etc.), but he still largely ignores the possibility of any sort of "intellectual appetite" for truth and goodness as such. Yet I'd maintain that it precisely these appetites that are strongest when properly roused. They are what have gotten generations of men and women to abandon all wealth and status and adopt celibacy to become monastics or ascetics, as well as generations of revolutionaries, abolitionists, etc., who have been willing to suffer brutal, anonymous deaths for causes they see as "truly best."

The flatness, and general skepticism about the human good and any human telos, makes defining virtue and proper ordering impossible. Defaulting on any claim the the human good, "freedom" becomes the ideal. But this is generally a sort of spare, procedural/legal freedom in conservative liberalism, with an added economic aspect in progressive liberalism. It just assumes that people become free upon reaching adulthood, provided they have enough material resources to meet basic needs.

Promoting, education, nudging, and law can all play a role in enhancing self-determination, and they can also frustrate it. Modern efforts tend to frustrate it because they simply assume that man is free so long as he can choose just whatever it is he currently desires (regardless of if he has chosen and affirmed those desires). -

The Christian narrative

Well, if you can't see the circularity in setting out the essence of cats in terms of catness, and catness in terms of what it is to be a cat, and what it is to be a cat in terms of essence, there's not much more to say.

So is everything that is irreducible also circular? Are definitions of mathematical objects circular?

Not something I'd agree with. It presumes that there is a something it is to being a cat...

Yes, that cats exist is an assumption here. The denial that cats, trees, or human beings exist is prima facie absurd though.

Simpler to just say that some individuals are cats.

So there is nothing that makes cats what they are, but then there are "some individuals who are cats?" Either the term refers to something specific to cats or it doesn't. Either there is something on account of which some individuals are called cats, or the term is arbitrary. So on account of what are cats called "cats?"

Further, an explanation of why something is called such is not the same thing as an explanation of why it is such, unless we are committed to linguistic idealism (which you often seem to be).

Telling, in it's way. You appear to think that the only alternative to essentialism is reductionism, so that's what you are addressing. But what is being mooted here is that we simply do not need access to an essence. Not even a reductionist one - if by that what you mean is "some set of properties."

Hardly. But @MoK seemed to suggest the reductionist thesis and you have defended the reductionist modal thesis time and time again as vastly superior, so that's what I responded to. Plus, it's at least more plausible than "there are no such things as cats, just the utterance "this is a cat."

Indeed, to say there are "individuals" called cats itself also suggests the question "in virtue of what are there individuals? When is something an individual?" If things are individuals just in case they are called such, then this explanation is hollow. It's just restating the fact that these words are used, which is undeniable (although, to be fair, so is the existence of cats as living organisms).

A particular picture of how language works has you enthralled. In that picture there is a something that is the meaning of a word, and the aim is to set out what that something is.

As noted above, essences are not about language or signification, except inasmuch that the former explains the causes of the latter (e.g., disparate cultures all developed a word for "ant" because there are ants). This is the same mistake your article makes, assuming that essences are entirely about philosophy of language.

Hence your rejection of Quine and Wittgenstein and most anything more recent than the French Revolution.

I don't think I'm disagreeing with Wittgenstein here. Wittgenstein is very careful not to tread into metaphysics. You frequently use Wittgenstein to make metaphysical claims that he himself does not make. Anti-metaphysics cannot make claims like "essences don't exist" without becoming metaphysics.

But sure, we agree that there are cats and trees.

How is this not a preformative contradiction. Aren't you arguing that there is nothing that makes trees trees and cats cats? Hence, you are equivocating here. I am saying, such entities as trees and cats exist, not that they are spoken about. You are essentially saying "yes, we use the word "tree" and "cat." But why do we use them? Presumably because these sorts of things exist. And indeed, the entire field of biology supports the conclusion that trees existed long before human language. The linguistic idealism at play here would make more sense if it was explicit, rather than relying on continual equivocations. If what makes a tree a tree is man saying "this counts as a tree," then there is an important sense in which trees did not exist before man and his language. But I'd maintain that such a claim is absurd. -

Referential opacity

Banno is right. Undistributed middle.

I think that's right, but the question of why it is more plausible seems to lie in the ability to equivocate on the way in which water, ice, and steam "are" H2O. It is, in some contexts, perfectly correct to say that ice and steam are water. A science teacher teaching the water cycle or phases of matter would say just this sort of thing. There isn't a correct context for "cats are dogs."

This is more obvious in a context where the relationship is more genuinely informative, such as "dry ice is carbon dioxide." It is true, in one sense, to point to dry ice and say "this is what you exhale," and obviously false in another sense.

You repay the money you borrowed, but not the same individual money - the very idea is meaningless

I don't think it's meaningless. Sometimes people hold money for other people, and they expect them not to mess around with it. Money is fungible though, so exchanging it isn't generally meaningful. It would be though if you had different sorts of bills, e.g. old precious metal backed bills.

You can refer to specific volumes of water. In a steam engine, we might talk exclusively about the water in a given system, and also its passage between different phases of matter. The difficulty in picking out individual instances of water (or air, etc.) would seem to have to do with their extremely weak principle of unity. It is very easy to divide volumes of water. Volumes of gas naturally expand. A water molecule is different. It has a stronger principle of unity. Solid water does as well, but you can easily break a block of ice apart and then you just have multiple blocks of ice. Compare this with something with a strong principle of unity like a tree. Break a tree in half and you have a dead tree, you have timber, not a tree at all arguably. Break it up more and you have lumber that is clearly not a tree. -

The Christian narrative

As if this were an explanation. Somewhat circular, no?

How so? At any rate, the "problem" you have identified exists just as much for reductionism. If we say a being a cat consists in having some set of properties then for each property we can ask, "and what does that consist in?" And this process can be repeated for each sub-property and the properties that define them. This will eventually have to either bottom out in irreducible properties (what you have claimed is "circular") or it will end up with us describing various properties in terms of each other in a circular fashion (although this does not appear to be a viscous circle). The problem will be just the same for popular forms of nominalism (e.g. tropes); it isn't unique to realism.

At any rate, that cats and trees exist seems obvious, hence the burden of proof for reductionism would seem to lie with the reductionist.

Yes that's a good point, although in context Rescher is talking about modern substance/superveniance metaphysics. He acknowledges early on (more than Heidegger IIRC) that Aristotle could rightly be classified as a process metaphysician to a good degree. As Paul Vincent Spade puts it, his via media between Parmenides and Heraclitus tends a good deal more towards the latter, because substances are always undergoing generation and corruption.

The Thomistic take on this same sort of argument is:

It is through action, and only through action, that real beings manifest or “unveil” their being, their presence, to each other and to me. All the beings that make up the world of my experience thus reveal themselves as not just present, standing out of nothingness, but actively presenting themselves to others and vice versa by interacting with each other. Meditating on this leads us to the metaphysical conclusion that it is the very nature of real being, existential being, to pour over into action that is self-revealing and self-communicative. In a word, existential being is intrinsically dynamic, not

static.

...by metaphysical reflection I come to realize that this is not just a brute fact but an intrinsic property belonging to the very nature of every real being as such, if it is to count at all in the community of existents. For let us suppose (a metaphysical thought experiment) that there were a real existing being that had no action at all. First of all, no other being could know it (unless it had created it), since it is only by some action that it could manifest or reveal its presence and nature; secondly, it would make no difference whatever to any other being, since it is totally unmanifested, locked in its own being and could not even react to anything done to it. And if it had no action within itself, it would not make a difference even to itself....To be real is to make a difference.

One of the central flaws in Kant’s theory of knowledge is that he has blown up the bridge of action by which real beings manifest their natures to our cognitive receiving sets. He admits that things in themselves act on us, on our senses; but he insists that such action reveals nothing intelligible about these beings, nothing about their natures in themselves, only an unordered, unstructured sense manifold that we have to order and structure from within ourselves. But action that is completely indeterminate, that reveals nothing meaningful about the agent from which it comes, is incoherent, not really action at all [or we might say, cannot be meaningfully ascribed to any "thing," i.e. as cause].

The whole key to a realist epistemology like that of St. Thomas is that action is the “self revelation of being,” that it reveals a being as this kind of actor on me, which is equivalent to saying it really exists and has this kind of nature = an abiding center of acting and being acted on. This does not deliver a complete knowledge of the being acting, but it does deliver an authentic knowledge of the real world as a community of interacting agents—which is after all what we need to know most about the world so that we may learn how to cope with it and its effects on us as well as our effects upon it. This is a modest but effective relational realism, not the unrealistic ideal of the only thing Kant will accept as genuine knowledge of real beings, i.e., knowledge of them as they are in themselves independent of any action on us—which he admits can only be attained by a perfect creative knower. He will allow no medium between the two extremes: either perfect knowledge with no mediation of action, or no knowledge of the real at all.

W. Norris Clarke - "The One and the Many: A Contemporary Thomistic Metaphysics"

This, of course, does not rule out the role of context in essences, which was a particular contribution of the Patristics in fully fleshing out, e.g.:

For all created things are defined, in their essence and in their way of developing, by their own logoi and by the logoi of the beings that provide their external context. Through these logoi they find their defining limits.

-St. Maximus the Confessor - Ambiguum 7

Or there is the Hegelian response, which is perhaps more relevant to 's original point.

Hegel's basic demarche in both versions [of the Logic] is to trade on the incoherencies of the notions of the thing derived from this modern epistemology, very much as in the PhG. The Ding-an-sich is first considered: it is the unity which is reflected into a multiplicity of properties in its relation to other things, principally the knowing mind. But its properties cannot be separated from the thing in itself, for without properties it is indistinguishable from all the others. We might therefore say that there is only one thing in itself, but then it has nothing with which to interact, and it was this interaction with others, which gave rise to the multiplicity of properties. If there is only one thing-in-itself, it must of itself go over into the multiplicity of external properties. If we retain the notion of many, however, we reach the same result, for the many can only be distinguished by some difference of properties, hence the properties of each cannot be separated from it, it cannot be seen as simple identity.

Thus the notion of a Ding-an-sich as unknowable, simple substrate, separate from the visible properties which only arise in its interaction with others, cannot be sustained. The properties are essential to the thing, whether we look at it as one or many. And so Hegel goes over to consider the view which makes the thing nothing but these properties, which sees it as the simple coexistence of the properties. Here is where the theories of reality as made up of ' matters' naturally figure in Hegel's discussion.

But the particular thing cannot just be reduced to a mere coexistence of properties. For each of these properties exists in many things. In order to single out a particular instance of any property, we have to invoke another property dimension. If we want to single out this blue we have to distinguish it from others, identify it by its shape, or its position in time and space, or its relation to other things. But to do this is to introduce the notion of the multipropertied particular, for we have something now which is blue and round, or blue and to the left of the grey, or blue and occurring today, or something of the sort.

-Charles Taylor - Hegel

The problem is not unrelated to the notion of haeccity introduced by Scotus. -

Referential opacity

Referential opacity is to do with individuals, not natural kinds.

Sure, but the issue is similar, as evidenced by the Israel/Palestine geographic area versus state equivocation.

I am not sure how the move to natural kinds explains the issue. If x is y natural kind and z is y natural kind, then in theory they have the same essential properties. If "water" is taken to be equivalent to H2O, i.e., chemical identity, then what is true of H2O is true for water. But water refers to both a chemical identity and a specific phase, which is what allows for equivocation, just as Israel can refer to a certain section of the Levant or the modern state of Israel, or the ancient Northern Kingdom.

But I'd argue that with the person/persona distinction similar sorts of equivocation can occur. Spiderman is the main character of a Marvel franchise. Peter Parker? Well, in the newer versions there is only Miles Morales from what I understand. -

The Christian narrative

I don't necessarily disagree with that. There is however, IMO, a quite good argument against "substances" that is advanced by process metaphysicians on this front:

To be a substance (thing-unit) is to function as a thing-unit in various situations. And to have a property is to exhibit this property in various contexts. ('The only fully independent substances are those which-like people-self-consciously take themselves to be units.)

As far as process philosophy is concerned, things can be conceptualized as clusters of actual and potential processes. With Kant, the process philosopher wants to identify what a thing is with what it does (or, at any rate, can do). After all, even on the basis of an ontology of substance and property, processes are epistemologically fundamental. Without them, a thing is inert, undetectable, disconnected from the world's causal commerce, and inherently unknowable. Our only epistemic access to the absolute properties of things is through inferential triangulation from their modus operandi-from the processes through which these manifest themselves. In sum, processes without substantial entities are perfectly feasible in the conceptual order of things, but substances without processes are effectively inconceivable.

Things as traditionally conceived can no more dispense with dispositions than they can dispense with properties. Accordingly, a substance ontologist cannot get by without processes. If his things are totally inert - if they do nothing - they are pointless. Without processes there is no access to dispositions, and without dispositional properties, substance lie outside our cognitive reach. One can only observe what things do, via their discernible effects; what they are, over and above this, is something that always involves the element of conjectural imputation. And here process ontology takes a straight-forward line: In its sight, things simply are what they do rather, what they dispositionally can do and normally would do.

The fact is that all we can ever detect about "things" relates to how they act upon and interact with one another - a substance has no discernible, and thus no justifiably attributable, properties save those that represent responses elicited from it in interaction with others. And so a substance metaphysics of the traditional sort paints itself into the embarrassing comer of having to treat substances ·as bare (propertyless) particulars [substratum] because there is no nonspeculative way to say what concrete properties a substance ever has in and of itself. But a process metaphysics is spared this embarrassment because processes are, by their very nature, interrelated and interactive. A process-unlike a substance -can simply be what it does. And the idea of process enters into our experience directly and as such.

Nicholas Rescher - "Process Metaphysics: An Introduction to Process Philosophy

The general point here being that processes seem to be more necessary than substance. But, against this we might consider one of the great weaknesses of many forms of process metaphysics, that they make all substances (things) essentially arbitrary and just end up positing a single, universal, wholly global process. That is, they collapse the distinction between substance and accidents. This turns out to just be the old Problem of the One and the Many, with the process answer being a sort of hybrid of Parmenides and Heraclitus, siding with Parmenides on the one hand vis-á-vis the unity of being (there being just one thing, the global process), but with Heraclitus on all being flux.

Against this, we can consider that activities and properties seem to have to be predicated of some substance. One does not have a "fast motion" with nothing moving, or nothing in particular moving. A dog can be brown, or light, but we don't have "just browness" with nothing in particular being brown. So we might suppose that some properties, even if they are processes, are parasitic on a different sort of process. Substances themselves are changeable (generation and corruption), yet there is something that stays the same between different instantiations of the same substantial form.

Second, there is an ostentatious plurality within being in that we are each individual persons; we experience our own thoughts and sensations and not other people's. Hence, there seems to be real multiplicity, and real unity as respects individual minds/persons. Essences are primarily concerned with the metaphysical principle by which things are the intelligible unities that they are. Thus, they are there to explain how there are specific properties in the first place. That is, they are primarily an explanatory metaphysical principle, rather than serving primarily to explain how words refer to different types of things. So, not our ability to pick out and refer to ants, but rather the fact that ants exist as a particular sort of thing and represent relatively self-determining and self-moving wholes.

Unity here occurs on a sliding scale, since unity and multiplicity are contrary, as opposed to contradictory opposites. Hence, the desire to pick out the exact limits of ants, people, trees, etc. in terms of superveniance is misguided. Physical substances are constantly changing. Their essence is the principle that explains how they are what they are.

Another difficulty with ignoring substances would be the fact that most of a thing's apparent properties only show up in particular contexts. Salt is "water soluble," but only ever demonstrates this property when placed in water (i.e., an interaction). Hence, the idea of potencies and powers.

Anyhow, an essence helps explain a thing's affinity to act one way and not any other. In terms of organism's, which most properly possess essences (i.e., are substantial unities rather than bundles of external causes) the essence helps explain the end/final causality related to the organic whole, and how an organism's parts are related to it as a whole (the idea in biology or "function.")

The problem with making essences into static sets of properties is that it:

A. Neglects how physical things are always changing (hence physus); and

B. Only really gets at the epistemic and linguistic movements of picking out types of things, not the actuality that must underlie their having their observed properties.

The article from @Banno is a sort of classical misunderstanding of universals/essences. It opens by pointing out that under realism they play some sort of a metaphysical role, and then presents an argument that presupposes that what is at stake is the use of categorical terms. If categorical terms could be otherwise, then there are not essences. If categorical terms are socially determined, then there cannot be essences (presumably because essences are just lookup lists of properties that link a word/concept to some things).

This misses the point entirely. Realists have generally not denied that terms are based on human ends and they don't deny that they are historically influenced. They don't deny that we can make up more or less arbitrary terms by dividing and concatenating intelligible wholes. Nor do they maintain that universals must exist for every common term. The rebuttal to the idea of essences is that there are not truly such things as tigers or trees, but rather that man finds it useful to name them such, and that this is what makes them so.

But the immediate question here would be "what caused this convention to be useful?" The most obvious answer is that there are such things as cats, flowers, etc. and that they are not ontologically dependent on language or man's will to exist as such. Nominalism seems to either end up acknowledging a prior actuality that is the cause of "names" (essence) or else (more commonly in recent thought) defaults into a sort of extreme volanturism where "usefulness" or "will" becomes an unanalyzable metaphysical primitive that chooses what everything is (i.e., John Calvin individualized or democratized; "In the beginning the Language Community created the heaven and the earth. The earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the soup of usefulness. And the Spirit of the Language Community moved upon the face of the waters. And the Language Community said, Let this be light: and thus it was light.")

Whereas the reductionist realist wants to say that essences can be reduced to properties because more basic actualities can explain more complex beings. The difficulty is showing that this is so. Exactly which set of actualities corresponds to catness and the organic unity of cats, or which component actualities combine to form man and his ends? Of course, there are higher, more general principles, but if these are analogously realized they are not subject to any univocal reductionism.

I don't know if I'd put it quite like that, although that is how commonly how it is put. Mystical author's like Saint John of the Cross or Saint Bernard of Clairvaux are extremely popular and influential in Catholicism. I would say rather that there are different stresses. The Orthodox put less focus on systematic theology, and so this makes mysticism more central to theological discourses. They also put a greater focus on asceticism in general. Just about half the days of the year are fast days, and recommended fasts tend to be more austere. I might say they are more praxis focused, at least in the Anglophone context, but even this seems hard to justify completely. They do make a very different distinction between the active and contemplative life. For Catholics, the active life is mostly service and evangelism, while the contemplative life is all forms of prayer, psalmody, the Hours, fasts, etc. For the Orthodox, all that latter stuff is also the "active life" and the contemplative life is strictly noetic prayer.

They are definitely different, but it's hard to say just how. The Rosary is in some ways similar to the Jesus Prayer/prayer rope. The Orthodox hours are more "noetic" in a way (they call out the nous in particular). I cannot think of a better word. They also seem somehow more inwardly, and thus individually focused in a way that I cannot quite put my finger on, even though they are also performed corporately. The biggest distinction is that they are vastly longer, too long really to be practical for the laity unless they are only keeping Matins and Vespers or Compline, whereas Catholic laity keeping the full Hours seems much more common. Their Lenten compline is legit an hour and a half long lol. -

Referential opacity

Sure, if you have something to add. I was just thinking of similar cases that don't involve belief. Another equivocation with proper names would be the provocative:

Israel is Palestine

Israel is a Jewish state

Therefore, Palestine is a Jewish state.

Which seems false, whereas:

Israel is Palestine.

Israel is considered to be the Holy Land.

Therefore, Palestine is considered to be the Holy Land.

Seems fine. I was thinking this is just old-fashioned equivocation between Israel and Palestine as names for geographic regions versus as names of political entities (you could do it with Tibet or East Turkestan "being Chinese" as well). You could disambiguate with "the state of Israel/Palestine." Wouldn't "Constantinople" / Istanbul just be a sort of special case of equivocation?

Edit: with Superman we could also avoid belief and still get an apparent error with "Clark Kent appears on the Daily Planet payroll." This might be considered the same sort of equivocation as "Constantinople"/Constantinople. It's not as immediately obvious though. One could say it is true in one sense and not in another that Superman appears on the payroll. -

Referential opacity

Sure, but you could easily make one that fits the form you were using. The difficulty there is that, in a simple three premise form, you end up with the questionable premise that "ice is steam." Well, that's true in a sense, but the whole point is that it is false in another. But you could do it in terms of a = c and b = c, which implies that a = b E.g.,

Ice and steam are H2O

Ice makes for a good bridge.

Therefore, steam makes for a good bridge.

You could also do it with the less questionable "ice is water."

Ice is water.

Ice makes for a good bridge.

Therefore water makes for a good bridge.

The problem here is an equivocation on "water" as chemical identity versus as a particular phase of that substance.

Now the error in the first is obvious in that H2O is sometimes treated as a sort of identity, chemical identity, (or a rigid designator) and yet the properties of its phases are distinct, and "ice" and "steam/fog" refer to particular phases. But I imagine a clever person could come up with less obvious examples. -

Referential opacityConsider the wholly nomological context of:

Steam is H2O

Ice is H2O

Therefore, steam is ice

This is obviously incorrect. So too:

Ice is H20

Fog is H20

Ice can be walked upon and makes for a good bridge.

Therefore, fog can be walked upon and makes for a good bridge.

Or another false argument can be based on the fact that ice becomes water when heated, yet steam does not.

And yet:

This water is water.

This water has become steam.

Therefore this steam is that water.

Seems fine. These are pretty easy to explain in terms of water. The interesting thing is rather the general form. With the last one, while it seems clear that my cup of water is the same water when it has frozen, consider:

These frogs are frogs.

These frogs have been digested and become a turtle.

Those frogs are this turtle.

...does not seem to work, although we might agree that in some sense the composition of the turtle bears a similar relation to the frogs as the ice to the water. -

The Christian narrative

Agreed. And we can hold that such an approach is diabolical while also maintaining that it need not be explicitly atheistic (for example). The issue has to do with a closed-off-ness to both analogical reasoning and transcendence.

Exactly. The rationalists are a prime example here. They generally have good aims, such as securing faith in reason, trying to resolve sectarian disagreements, creating a firm foundation for a wholly instrumental science based on the "mastery of nature" for the benefit of man, etc. They were, in general, religious. But there is a neglect of praxis here that cuts against tradition and Scripture, and a move towards instrumentalizing and proceduralizing reason and wisdom. And when they are unsuccessful in an approach that is almost wholly ratio, the result is skepticism, but also a view of the nous that is no longer radically open to what lies above it, and a participation in a greater Logos.

I'd suggest that the sheer instrumentality of the "new science" is a major culprit here. It leads to a sort of pride. It's a particularly pernicious pride in that it often masquerades as epistemic humility. Its epistemic bracketing is often an explicit turn towards the creature and the good of the creature without reference to the creator, as if the one could be cut off from the other. "Professing themselves to be wise, they became fools," and exchanged a holistic view for a diabolical process that cuts apart and makes it so that "reason is and ought to be the slave of the passions." -

The Christian narrative

But you can't make an apology for the Catholic view by referring to Eastern Orthodox. Let's just leave it at this: on it's face, the Catholic Trinity appears to be contradictory