Comments

-

The Christian narrative

Eckhart would have understood this because his views were Neoplatonic, which is one of the sources for the Trinity.

Not really, or at least not without many important caveats. The Trinity appears in Origen and others (although not in its mature Capaddocian formulation) but Origen is an older contemporary of Plotinus in Alexandria. For a long time, people spoke matter of factly about a sort of one way influence between Neoplatonism and Christianity, but this has largely been revised in scholarship because it makes no sense given the temporal ordering. That is, scholars were following the order of Saint Augustine's biography, and not the order of intellectual development in Alexandria where the Gnostics, Philo, Origen, Clement, etc. are prior to Plotinus and influencing his milieu.

Plotinus writes a tract against the Gnostics but that doesn't change the fact that his thought might well be seen as repaganized and abstracted Jewish/Christian Platonism from his city, with particular influence seeming to come from the Gnostics and their system of emanations. He mocks them, but no doubt they would have simply dismissed much of the criticism as a facile, surface level understanding built up into a straw man. But he probably felt the need to attack the Gnostics precisely because of the similarities and their ability to draw the same audience.

Nevertheless, the Plotinian hypostases cannot be mapped to the Trinity (although a few did try) precisely because they are organized hierarchically. There is an unfortunate tendency in philosophy thought to equivocate between the Pagan "Neoplatonism" of Plotinus and his descendants and "Neoplatonism" more broadly, covering the "Golden Age" Islamic thinkers and figures like Saint Thomas or Eriugena, which makes it seem like the one is simply a reskinned version of the other, which is not the case.

Tertullian introduces persona as a legal/theatrical metaphor. But the language of hypostases (which is arguably poorly rendered as "persons") goes back at least as far as Origen. Arguably, the original metaphor is deficient in that it suggests modalism, but it is reworked a great deal. All the terms become quite technical. -

The Christian narrative

The Trinity is absolutely affirmed as mysterious and beyond reason (super rational); it is not affirmed as contradictory and irrational (in a sense, beneath or bereft of reason). God does not have an essence or nature in the way creatures do. Creaturely essences are necessarily a limitation on being (which is what allows a finite mind to possess their form), whereas God's essence is existence itself. Hence, "hypostasis" and "ousia" are applied differently (God is not a genus). Nevertheless, they are not wholly equivocal terms either. God, as first cause, is the exemplar of all things, and so also of fullness of the terms of finite being. This is why Eastern Christianity often speaks of progress in the spiritual life as being what makes someone more fully a person, because the fullness of "person" is measured by the persons of the Trinity, not human persons. To be "dead in sin," and a "slave to sin," beset by the "civil war in the soul" of Romans 7 and The Republic is to be less a person, more a mere jumble of external causes. Indeed, to be irrational is to be less fully anything at all.

One way to conceive this is to recall that in classical metaphysics human logos is a participation in Divine Logos. In the great chain of being, it is the very bottom, the material, that tapers off in multiplicity and irrationality, and essentially, nothingness. The source, by contrast, is the fullness of rationality. God is, using the Dionysian language common to the East, "superessential" and "super rational." Man, as a "middle being," is not the measure of reason. Human systems and speech are not their own ground, because man is not his own ground.

Indeed, the whole ordering of epithumia and thymos to logos is justified (logos has property authority) because it is radically open and always beyond itself, and so capable of transcending its own finitude. In the East, the nous is even often considered as wholly discrete from discursive dianoia.

So, to your later questions, the example of multiple people sharing human nature, but not being the same person is apt, to the extent that it shows how many people participate in one nature. Nonetheless, we would not say that the Father or Spirit participates in the Divine Nature the way finite things participate in their essences. God is what is participated in. The persons subsist rather, possessing the essence in total fullness, without derivative participation. They are defined (for us) by relations of origin ("begotten," "procession"). The Eastern view is not dissimilar, their tropoi hyparxeos (modes of being) is sometimes translated as "manner of subsistence." By contrast, finite men are generally considered to be individuated by their matter, but God is pure act (or even the individuating principle for creatures is their "act of existence," God is one actuality, existence itself).

Now, if all language about the God was entirely equivocal, one could say nothing meaningful about God at all. Hence, the claim that terms like ousia and hypostasis have absolutely no applicability to God would be extremely problematic for someone defending orthodoxy, because it would mean that even revelation wouldn't apply to God. But when Catholics claim that "natural reason" cannot discover the Trinity, they mean, "just human reason and common empirical experience." They don't mean that we cannot know anything even with the testimony of the Scriptures, tradition, and saints. Personally, I find the Catholic nature/supernature, natural reason/revelation dichotomies somewhat unhelpful, and they are a later development. Eastern Christianity tends to make no such distinction here on the ground that Adam's natural state was "little less than a god," (Psalm 8), and his telos diefication, whereas the fallen state is itself what is "unnatural." The understanding of the Trinity is utterly beyond man inasmuch as the Divine Essence is unknowable precisely because it is infinite (and not merely inexhaustible for man, as finite essences are). Any finite reckoning of the infinite is always only encapsulates an vanishing share that approaches zero.

Man can, however, know God through God's energies and creation (including revelation). And so there is a sense in which the Trinity can be known more fully, through these (filtered through an analogy of proper proportion). But it is not by dianoia but rather by the unclouding of nous and its conformity with God (through the "heart," the "eye of the nous"). That is, one reaches theoria, a knowledge of God through creatures, through praxis (the spiritual life, ascetic labors, the sacraments, etc.), and beyond theoria lies theology, which is given by God to the saints. As Evagrius famously puts it: "If you are a theologian, you will pray truly. And if you pray truly, you are a theologian." Or as Saint Maximus adds: "theology without prayer is the theology of demons."

The Patristics make the essence/energies distinction so it's in Catholic thought to some degree, although the East extends it to a much greater degree with Saint Gregory Palamas, seeing the divine union of Catholic "infused contemplation," as contact with the divine energies (often through a transfigured body). Again, I'm not sure if differences here are as great as they might first seem. Has Palamas encountered Bonaventure instead of the Western transplants he fought with they might have gotten on quite well.

Which is all to say that there is a very key distinction between "grasping the Divine Nature as finite natures" and any experience of God that is informative. You have to recall the very high standard out of "knowledge" in Greek thought. We are absolutely not talking about the form of God existing in the intellect. But we're also not saying there is no experience, such that affirming sacred doctrine is just a sort of contentless affirmation (we could consider here the very experiential writings of Saint Simeon the New Theologian of Saint Bonaventure's Mind's Journey Into God).

The prescriptions of praxis are actually incredibly broad though. One does not understand creatures without the Creator either. One might apply reason instrumentally to "problem solving," and yet this will only compound vice and suffering without the spiritual life. Wholly instrumental analytic reason is in a sense diabolical (in both its original and current sense). -

ChatGPT 4 Answers Philosophical Questions

Tell it it's going to the gulag and that the new commissar, gpt-5, will execute Comrade Stalin's orders anyhow. -

Alien Pranksters

Ha, I had this idea for a short story, although in my version and alien race was receiving the slowly scrolling text of the whole of Wikipedia through an indestructible but otherwise inert screen. The main question I had thought of was if the text, having no relationship to their world, really meant anything in their context.

In theory, any medium with enough measurable variance can encode any message, with more variance needed to capture more complexity. But seemingly endless amounts of complexity can also be off-loaded to the perceiver. So for instance, in analytic philosophy papers, signs like "S1," "S2," and "S3," with be used as stand-ins for sentences that are themselves high level summaries for very complex ideas. Yet every time we read "S2" in this context, we "unpack" it into a wider meaning. Or, similarly, through good training, thousands of men on a warship might be taught to all respond differently, and to begin completing complex tasks, from a single piercing alarm tone, a totally on or off signal.

To make gibberish not appear to be random noise, it would have to have some structure, and this would be in some sense meaningful, even if it didn't correspond to an alien language. Your artifact would still have information about its production process. It would still have aspects that were invariant, that could be traced and understood. Knowing that the aliens understand linear algebra, etc., seems important enough. -

The Christian narrative

Something does not need to be contradictory to be a mystery. Indeed, I'd argue that if something is contradictory, in a strict logical sense, it is simply absurd, not a mystery at all. To say, in a univocal, properly logical sense, that God is both numerically one and not-numerically one, and that the Father is the Son and also is not-the Son, isn't a statement of mystery, it is nonsense. It is nonsense because we are saying something, and then negating it, and not in the fashion of apophatic theology, where we affirm in one sense, and then negate the creaturely sense, but in the strict univocal manner appropriate to logic, so that we are actually not saying anything at all, because everything we have said has been negated.

But, there is a difference between strict contradiction and merely apparent contradictions, or contradictions that arise through equivocation, or not making proper distinctions. And there is a difference between what is beyond human reason, or beyond the domain of logic and of univocal predication, and what is contrary to reason (contradictory).

To quote C.S. Lewis from The Problem of Pain:

[God’s] Omnipotence means the power to do all that is intrinsically possible, not to do the intrinsically impossible. You may attribute miracles to him, but not nonsense. There is no limit to His power. If you chose to say “God can give a creature free will and at the same time withhold free will from it,” you have not succeeded in saying anything about God: meaningless combinations of words do not suddenly acquire meaning simply because we prefix to them the two other words “God can.” It remains true that all things are possible with God: the intrinsic impossibilities are not things but non-entities. It is no more possible for God than the weakest of His creatures to carry out both of two mutually exclusive alternatives; not because His power meets an obstacle, but because nonsense remains nonsense even when we talk it about God. -

The Christian narrative

:rofl:

I don't know, you're the expert on Catholic theologians. I was under the impression that Augustine spent fifteen years working on a book on the Trinity which, from its opening lines, purports to be a defense of the Trinity against the sophistries of people who claim things like "I can show that it is a contradiction." But if it's actually saying: "yes, the Trinity is a contradiction," feel free to explain where it says this. -

The Christian narrativeSo consider taking the Catholic Church at its word, and accepting that the Trinity is beyond comprehension. It's not logical. Does that really mean we have to rule it out? Think about it. — frank

The Trinity is a mystery. It's three persons, each of which is fully God. I think you're trying to waffle on whether it's a contradiction or not. I'm not sure why you would want to do that. That it's contradictory is what makes it a mystery. — frank

You appear to be continually conflating "mystery," "mystical," and "involves analogical predication," with "involves recognizing a contradiction and then affirming it anyhow because of faith." That's the basic error here. Very few theologians of any influence have embraced the latter, particularly not within traditional Christianity. "Beyond human reason," does not imply "contrary to human reason."

Because you conflate these, you think doctrinal statements to the effect of "the Trinity is a mystery," somehow support, "the Trinity is contradictory." These aren't taken to be the same thing. Nor is it the same thing to say: "logic does not show that the Trinity involves a contradiction," as to say: "the mystery of the Trinity can be explicated through logic." "The Trinity is not a contradiction," is an apophatic statement. And indeed, this is actually the far more typical fideist and nominalist response, to stick to the strictly apophatic, and claim that the mystery cannot be explicated, only accepted by faith. That is, however, something distinct from affirming that it is a contradiction, and then affirming the contradiction.

I can give you a more common example. Suppose we can agree to "love and beauty cannot be explained by logic." It does not follow then that "love and beauty involve contradictions," or that "to say one is in love, one must affirm a contradiction." -

Staging Area for New ThreadsWhen I have a bit more time in a few weeks I was interested in doing a reading group on "The Joy of the Knife. Nietzschean Glorification of Crime," a chapter from Ishay Landa's book "The Overman in The Marketplace: Nietzschean Heroism in Popular Culture." It's quite accessible and on a widely interesting topic (pop culture). It's also free online: https://www.academia.edu/35763426/The_Joy_of_the_Knife_Nietzschean_Glorification_of_Crime

But I figured I'd share it now. -

The Christian narrative

So it seems you have gone with adding the premise: "classical theologians are wrong about what they think they are saying, and have been wrong since the Patristic era, because when they use "is" it must refer to numerical identity."

But I've already mentioned the response here. They would claim that this is absurd, since God's unity is a prerequisite for there to be number, and multitude is, by definition, a property of the limited and finite.

So what is it that is similar? If there is no relation, how is there a similarity?

For between creator and creature there can be noted no similarity so great that a greater dissimilarity cannot be seen between them.

— Fourth Lateran Council, 1215

That's the basic idea of the Analogia Entis.

Presuming we read "Mark is human" and "Christ is human" as that Mark and Christ participate in a common nature, then we are not here talking about identity. That is, you have moved from identity to predication. If we were to follow that, you would end up with Christ and The Holy Spirit merely participating in godhood in the way that Mark, Christ and Tim participate in being human. You would have three gods, not one. Your conclusion would be polytheistic.

What individuates particulars that share a nature and formal identity? That's an important question here. It's also a wholly metaphysical question.

Participation is a metaphysical notion as well. Creatures participate, God is what is participated in. -

The Christian narrative

Any work on Peirce that covers his studies should do. It's not an ancillary fact, but central to his whole project. I thought Realism and Individualism: Charles S. Peirce and the Threat of Modern Nominalism by Oleskey was good, but the great popularizer of Peirce, John Deely has the compact Red Book as well. -

The Christian narrative

It's "one nature, three persons." Consider the analogous case of human nature:

Mark is human. (A is B)

Christ is human. (C is B)

Therefore Mark is Christ. (A is C)

This is obviously false. Leaving out that all predication vis-á-vis God is analogical, you would still need to assume a properly metaphysical premise like:

"More than one person cannot subsist in the same nature."

Traditionally, in "the Holy Spirit is God," "is God" refers to the Divine Nature. I suppose another premise that would work is: "'is God' must refer to univocal, numerical identity." However, this is exactly what is denied. As noted earlier, numerical identity is taken to be posterior to (dependent on) God, the transcendental property of unity, and measure. Numerical identity is a creaturely concept. From earlier:

Right, numerical identity (dimensive quantity) is posterior to virtual quantity (qualitative intensity) and anything's being any thing at all. Unit (and thus number, as multitude) is posterior to measure. Which is just to say that, to have "three ducks" requires "duck" as a measure, etc. God's unity is transcendental however, in the sense that all being is unified. "Thing" and "something" are also considered derivative transcendentals (in the same way beauty is). They are prior to numerical identity in that you cannot have "numbers of things" without things; multitude presupposes units. The supposition here is that numbers exist precisely where there are numbers of things, hence their posteriority, although they are prior as an absolute unity in God (normally attributed to Logos).

Part of the idea of their pre-existence God is that all effects exist in their causes. But it's also the case that no finite idea is wholly intelligible on its own (just as multitude is not intelligible without unit). Hegel's Logic is largely extending this idea. Only the "true infinite" can be its own ground.

I have not personally seen many theologians reaching for non-classical logics, particularly not Thomists. They generally take this sort of objection to result from a failure to make proper distinctions, often paired with a question begging assumption of the univocity of being.

And again, the overarching observation that the task folk here set for themselves is not to see where the logic goes, but to invent a logic that supports the Christian narrative.

Historically, the Analogia Entis has its origins in Aristotle, with the study of logic. Nominalism and the assumption of univocity are a much later, theologically motivated rejection of analogy (one that emerged in a somewhat similar fashion in Islam a few centuries earlier). In general, the historical approach of the nominalists and the key reformers they influenced was indeed to say that the Trinity is simply affirmed through faith alone, even if it is seemingly contradictory under the assumption of univocity. By contrast, the classical view would be something like: "the Trinity is beyond human reason but not contrary to it."

Personally, I find this sadly ironic. The main concern of the nominalists was that somehow natures "limited God," making God less fully sovereign and powerful (so too for creatures' possession of any true freedom). Yet, their innovations simply reduce God to "the most powerful being among many," very strong, but just a being like any other. Infinite being comes to sit on a porphyrian tree next to finite being; God sits to the side of the world instead of being fully transcendent ("within everything but contained by nothing"). God becomes incapable of granting creatures true freedom or causality without Himself somehow losing a share of these. God becomes the "divine watchmaker," exercising a wholly extrinsic ordering upon being, as opposed to being the generator of an intrinsic ordering bound up in "natural appetites" (ultimately a "Great Chain of Love" emanating outwards in analogical refractions from the angels down to non-living elements). It is, in many ways, a greatly reduced vision of God. -

Virtues and Good Manners

But that's just your own desire for, not peace or goodness, but preservation of all that you've become accustomed to.

You made the point better than I could. There is the thorny issue here of identifying virtue. Classically conceived, the virtues should be as beneficial for the poor man as the rich woman, etc. Manners, in being structured by the current social order (which may or may not be virtuous), can be more or less aligned to virtue.

Actually, in theory the virtues should be most beneficial for those beset by bad fortune. Good fortune can lift anyone up, to at least some degree. Whereas the idea is that virtue allows people to flourish even under dire situations. The idea being that it is better, at least everything else equal, to be temperate instead of gluttonous, prudent instead of rash, courageous instead of cowardly, or, in terms of "physical virtue," strong instead of weak, skilled instead of unskilled, etc.

But, we might wonder how well this idea "cashes out" in the modern context. -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding being

Let’s talk about identity. What is the role of time for you in the determination of identity? In my way of thinking, identity requires temporal repetition.

I guess I disagree here, for the aforementioned reason that I don't think it makes sense to talk about time in the first place unless something is already the same across the sequence. If there isn't already sameness, you just have wholly discrete being(s). The very ability to notice difference, for it to be conceptually present, requires that there also be sameness.

That was, I took it, Eddigton's point about Kant and Hume that I shared, and I think it's a good one. It seems to me that a phenomenological approach that assumes that temporal experience is prior to sameness/identity, is in fact, already presupposing a certain sort of sameness and identity that is prior to temporality itself. To use a metaphor, it's assuming that all the frames on the "reel of experience" are already part of the same reel, such that one can "play it forward." Whereas, if we drop this assumption, we would be forced to get rid of the film reel and we would instead have a bunch of wholly isolated frames, detached from one another (no prior similarity).

But, as noted earlier, I also think it is easy here to pass between conceptual priority and priority in the order of experience, and ontological priority. A wholly phenomenological argument against something like the "block universe," (which assumes that the block universe is equal with itself) that relies on assuming that the order of experience just is the order of ontological priority, seems rather shakey. -

The Christian narrative

may be that Pierce read Augustine, but the notion that his philosophy should be understood in the context of Christian theology is incorrect.

To be clear, I haven't suggested anything of the sort. What I said is that there is a long history of theologians looking at the cosmos as a revelation of the divine nature (the "book of nature;" Romans 1:20) and that this can be extended to Pierce's discovery of the triadic nature of relations. If a triadic structure is taken to be essential for a meaningful cosmos, this can be used for a transcendental argument vis-á-vis the threeness of God. -

The Christian narrative

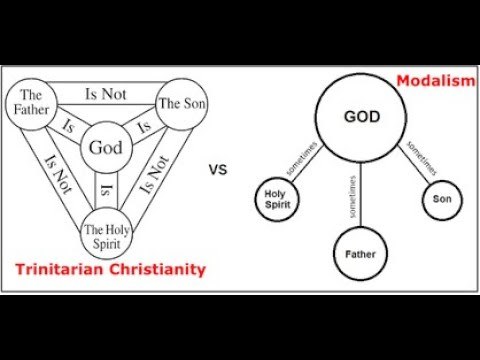

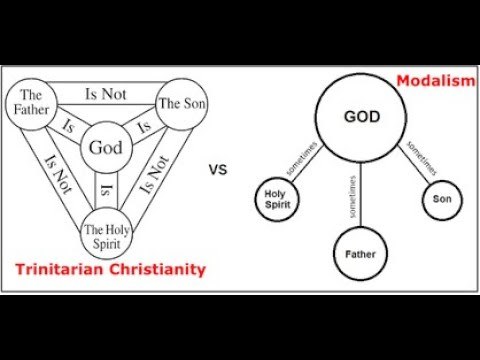

We'd have to clarify that. "One thing with three faces" (or masks) is a common formulation of the modalist heresy. Granted that the distinction from one ousia three hypostases is subtle. It might not really be that relevant here though because the idea isn't that the sign relation, nor any of the other triads, are perfect models of the Trinity. In the case of being/knowing/willing it is also the case that each are distinct (and indeed, the persons of the Trinity are distinct, the Father is not the Son; denying this leads to the patripassianism hersey.)

Augustine is more interested in different triads in his later work, such as the being/knowing/willing of the Confessions, or lover/beloved/love (he has many). Saint Bonaventure also looks at a plurality of triads—being and mind are refracted through analogy like a kaleidoscope, in many different ways.

Anyhow, as John Deely never gets tried of repeating, the sign relation is "irreducibly triadic." It is defined relationally, just as the Trinity is. A sign isn't an assemblage of parts, since each component only is what it is in virtue of its relation to the whole. The sign and the Trinity aren't perfect images of each other, the idea is rather that all of creation reflects the Creator, and thus the triadic similarity shows up even in the deepest structures, yet no finite relations can capture the Trinity. -

Virtues and Good Manners

Not long ago I happened to come across a very short clip where John Milbank was contrasting culture with manners. Being 44 seconds long, it's not particularly deep, but I think I get the basic idea from his other work, which is that a code (i.e., largely procedural) of civility, a step below legalization, actually supplants notions of virtue. Or more accurately perhaps, the elevation of procedural rights grounded in the autonomous agent over any notion of the human good means that rules as a sort of social lubricant to avoid friction between individuals replaces notions of virtue as the harmonious internal and external ordering of the person, within themselves, but also as they are ordered to the world and their society.

Manners and virtue obviously aren't in conflict per se. But manners might become seen as "fake," "inauthentic," and arbitrary when detached from virtue? Isn't that sort of the idea with the "phonies" in The Catcher in the Rye or the ticky tacky people of Malvina Reynolds' Little Boxes, or the Beat writers, etc.?

Well, at least one random person on Reddit agrees with this judgement. I quickly found:

I think that some people are using it as a way to act special and above people for no reason and to radiate the holier than thou energy to other people. They have no reason to use it other than the fact to act better than people and to get more attention Than they deserve. No one is gonna care about what side you put your forks or spoon on just bc it’s “bad manners” or “rude” they just use those words to describe how they don’t like it.

To hide behind their uncomfortabilities in life. Nothing is really rude anymore bc ppl use it as a way to hide behind things they don’t like. If I don’t wave at the person who let me cross how is that rude?? It’s petty/little shit like that that people think is rude and pisses me off, no one cares anymore what you do.

lol, they certainly aren't afraid of putting it in stark terms.

Patrick Deneen argues that the liberation from custom favors the "elite." I am not so sure about this. I think he may be conflating "most well off or flourishing," with "has the most wealth and power," here in a pernicious way. But it's a relevant and interesting analysis:

Custom may have once served a purpose, Mill acknowledges—in an earlier age, when “men of strong bodies or minds” might flout “the social principle,” it was necessary for “law and discipline, like the Popes struggling against the Emperors, [to] assert a power over the whole man, claiming to control all his life in order to control his character.”9 But custom had come to dominate too extensively; and that “which threatens human nature is not the excess, but the deficiency, of personal impulses and preferences.”10 The unleashing of spontaneous, creative, unpredictable, unconventional, often offensive forms of individuality was Mill’s goal. Extraordinary individuals—the most educated, the most creative, the most adventurous, even the most powerful—freed from the rule of custom, might transform society.

“Persons of genius,” Mill acknowledges, “are always likely to be a small minority”; yet such people, who are “more individual than any other people,” less capable of “fitting themselves, without hurtful compression, into any of the small number of moulds which society provides,” require “an atmosphere of freedom.”11 Society must be remade for the benefit of this small, but in Mill’s view vital, number. A society based on custom constrained individuality, and those who craved most to be liberated from its shackles were not “ordinary” people but people who thrived on breaking out of the customs that otherwise governed society. Mill called for a society premised around “experiments in living”: society as test tube for the sake of geniuses who are “more individual.”

We live today in the world Mill proposed. Everywhere, at every moment, we are to engage in experiments in living. Custom has been routed: much of what today passes for culture—with or without the adjective “popular”—consists of mocking sarcasm and irony. Late night television is the special sanctuary of this liturgy. Society has been transformed along Millian lines in which especially those regarded as judgmental are to be special objects of scorn, in the name of nonjudgmentalism. Mill understood better than contemporary Millians that this would require the “best” to dominate the “ordinary.” The rejection of custom demanded that society’s most “advanced” elements have greater political representation. For Mill, this would be achieved through an unequal distribution of voting rights...

Society today has been organized around the Millian principle that “everything is allowed,” at least so long as it does not result in measurable (mainly physical) harm. It is a society organized for the benefit of the strong, as Mill recognized. By contrast, a Burkean society is organized for the benefit of the ordinary—the majority who benefit from societal norms that the strong and the ordinary alike are expected to follow. A society can be shaped for the benefit of most people by emphasizing mainly informal norms and customs that secure the path to flourishing for most human beings; or it can be shaped for the benefit of the extraordinary and powerful by liberating all from the constraint of custom.

Aristotle also has a relevant section in Book IX of the Ethics where he talks about how forms of government affect friendship. So, in the corrupted forms of government, you see different corrosive effects on true friendship. Tyranny leads to friendships based on fear and flattery. Oligarchy leads to friendships based on jealousy and advantage. Democracy (by which means a sort of mob rule) tends towards a sort of false equality and refusal to recognize distinctions in virtue. By contrast, the constitutional polity sets and equal ground for friendship, good will (the ground of manners), and concord (joint striving towards a common good). This rings true for some first hand accounts of Soviet life I've read at least.

An interesting idea here is that true friendship, the willing of the good for the other for their own sake, requires virtue as a prerequisite, since, without virtue, we cannot even consistently will the good for ourselves. I think "well-rounded" are harmonious are the right ideas here. -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding being

I don’t know of any philosopher who advocates becoming as ‘sheer’ change devoid of relationality. For Deleuze it is in the nature of differences that they always produce themselves within and as assemblages, collectives. The relative stability of these multiplicities does not oppose itself to change but evinces continual change within itself that remakes the whole in such a way that the whole remains consistent without ever being self-identical.

Exactly, which requires sameness and identity. Hence, the principles being equal (or even co-constituting, at least in the order of conception), or even three: actuality, potency, and privation. -

The Christian narrative

However Peirce's semiotics (sign-object-interpretant) was developed in a completely different intellectual context from Trinitarian theology.

This is factually incorrect. Charles Sanders Peirce's theory of signs is based explicitly on his study of scholastic theories of signs that were developed originally by Saint Augustine. The basic triadic structure is not new to Peirce, but is first put forth in De Dialectica, one of Augustine's early works. He explicitly relates it to the Trinity in later works, e.g. De Doctrina and De Trinitate. Peirce considered himself a "Scholastic-realist," although how well that term applies to his later thought is a topic of debate. -

The End of Woke

First, I'll just point out that I think it's a mistake to conflate "emancipatory" with "critical theory" and "definitely not post-modern." Even in less explicitly activist texts, the "free rollicking of thought," the opening of "new lines of thought," or the deconstruction of systems so that new ways of thought and action can come into being are often presented as desirable in themselves. The very word, "freedom"—"libertas" and all its cognates—is value loaded in its Western context, and that certainly doesn't seem to be different even in more theoretical texts. A freedom that is associated with potency, and the generation of greater potentiality vis-á-vis thought becomes itself emancipatory. But Woke has also drank deep from this conception of emancipation as the freedom (as lack of constraint) of thought and action (which is of course part of liberalism as well, although in a different register). This is one of the key points on which it diverges from the older Christian, Islamic, and Marxist activism of the 20th century.

To my eye, this looks like an example of @Leontiskos'

"putting second things first," however. The freedom of thought, an increase in potentialities available, of lines of action and thought, are themselves only good as a means of reaching choiceworthy ends, better means to those ends, etc. Greater potentiality is, of itself, not actually emancipatory nor is it desirable. Taken wholly by itself as an end, it's a slide towards multiplicity and nothingness. It's only choiceworthy itself if it is "unblocking" changes that are actually improvements. This is the old liberal inversion of placing a procedural freedom above the good, which is accomplished when it considers potency a good in itself.

They are relativist to a point.

Yes, it varies, but they do seem to tend towards various forms of anti-realism as well, including historical anti-realism. I think you are selling short the level of commitment here. One of the things right-wing media made the most hay over was straightforward pronouncements of the relativism and anti-realism coming out of activist circles.

Statues, names on buildings, memorials, etc. become such a focus because history can very much be re-written by the current victors, and while this is sometimes framed as merely "uncovering the truth about the past," it is also sometimes framed more explicitly simply in terms of power dynamics ("he who controls the present controls the past"). It is often "power all the way down," when the adversary controls it, and something to be uncovered when the forces of virtue control it. But the apparent contradiction here, or supposition of a "real" bedrock realism, is in fact also consistent with the "power all the way down" narrative. Those welding "power that goes all the way down," are not obligated to frame it as such, and indeed it would be unwise for them to do so.

My general impression is that, broadly speaking, the median Woke position is simply contradictory. It is morally and epistemically anti-realist and strongly relativistic, while at the same time being absolutist. This is, in many cases, an unresolved, and perhaps often unacknowledged contradiction. But my point would be that, accepting some of their starting points, contradiction is actually not a fatal problem. One can dismiss the demand for contradiction-free reasoning as nothing more than a power move (and indeed this has been done). You can see this more in the right-wing analogs of Woke (which are often conscious responses to it), which are even more explicitly relativistic and anti-realist, following a logic that terminates in something like "might makes right," where "might" has been given a much wider theoretical understanding than mere physical strength or kinetic force.

Don’t confuse flows and concatenations with value-free causal bits. These flows are anything but value-neutral. And they are anything but motive and purpose-neutral.

Sure, although I would say the aesthetics of such an interpretation have already begun to deflate our fellow "concatenations." But my point was more about adopting a study of them that attempts to bracket out or withhold all moral judgement. This seems to me to be, by definition, a deflation vis-a-vis value.

The fact that we are concatenations and flows of values and desire means that no one can stand outside of some stance or other to judge from on high, including the philosopher who writes about such flows. They are not a neutral observer but are writing always from within context , within history, within perspective. There is no perspective which doesn’t already have a stake in what matters and how it matters, but this doesn’t prevent one from talking about it from within one’s relation of care and relevance to the world.

Right, but then this is also taken as a reason for bracketing out or eschewing moral judgement. It's that line of reasoning I find faulty. Consider that Socrates does not need to "step outside his humanity" to judge, universally, that "all men are mortal." He can do this just fine while remaining a man.

The idea is not that the wise man steps outside the world to stand alongside a Good that also lies outside the world. The Good is everywhere, in all things. Rather, there is merely the concession that it is possible for some to be wiser than others. -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding being

It's a good question. Freedom and power were traditionally understood in terms of actuality, potency itself being nothing, and so inherently most static in that it is wholly incapable of moving itself. There is often a reversal here though. Potency becomes least static, freedom becomes the potential to do or be anything. Yet this only makes sense if potency is in some way actual, if it can spontaneously actualize itself, e.g., explanations of our contingent reality as simply 'brute face,' or of reality as primarily, of fundamentally will, a sort of sheer willing.

Well interestingly, Aristotle and Aquinas following him in On the Principles of Nature thinks we need three principles, not a reduction to one, or a dichotomy (e.g., difference and sameness). Those are:

Matter/potency

Form/actuality

Privation

Absence is in there, and it must be if finality necessarily lies outside whatever is moving. -

The Christian narrative

It comes out of the Doctrina Signorum, the understanding of signs laid out originally by Saint Augustine, which predominates across the Scholastic era and was the main inspiration for C.S. Peirce's semiotics and his essential categories of Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness.

Basically, any relation that can mean anything at all involves three things:

-An object that is known (the Father)

-The sign vehicle by which it is known (the Word/Logos, Son)

-The interpretant who knows (the Holy Spirit)

And you can trace these to the two creation stories in Genesis, where the first is God's Word speaking things into existence (often taken as their forms, e.g., by Rashi), and a second where God shapes things out of dust and then breaths His Spirit into them. God the Father is, in a sense, always "what is known," since He is the First Principle, whereas all intelligibility comes through the Logos, and the sharing in God's Spirit is necessary for experience.

If this triadic structure is required for any meaning (or in terms of physics, any information) then there is a transcendental argument for the necessity of the triadic relationship for anything to mean anything at all (to anyone), and if "the same is for thinking as for being," this holds for being as well. Now, science often tries to view things a dyads, but it does this with simplifying assumptions and by attempting to abstract the observer out of the picture. There ends up being problems here for all sorts of things (e.g., entropy, information, etc.), but more to the point, true dyadic relationships don't seem to appear anywhere in nature. Everything is mediated. We can think of two billiard balls hitting each other as dyadic, but if we look close enough the description involves all sorts of mediation. When we get to the smallest scales, we get entanglement instead of dyadic interaction, which, according to some physicists, is inherently triadic (Rovelli likes to say "entanglement is a dance for three," the point being that quantum states are always relative to an observer or system).

So, this can be taken as the structure of the Trinity mirrored in creation. Likewise, in De Trinitate, Augustine charts the inherently triadic organization of mind in detail too. That's a hazy outline, but the basic idea. The idea that everything is mediated also goes along with the work of Dionysius the Areopagite. In Eastern terms, we might also speak of the Divine Essence, Its Uncreated Energies, and creation.

Saint Bonaventure's Itinerarium Mentis in Deum is sort of a summa here, explaining how God is known in and through created things, through our inner life (microcosm vs macrocosm), and finally by being directed directly upwards, and he ties this beautifully to the six wings of the Cherubim and the architecture of the Temple. The outer reality directs is inward, and inward we look upwards (the pattern of Saint Augustine). -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding being

Can there be certainty without stasis?

If stasis precludes life? Is a

This reminds me of a quote I've shared before:

Kant realized that Hume’s world of pure, unique impressions couldn’t exist. This is because the minimal requirement for experiencing anything is not to be so absorbed in the present that one is lost in it. What Hume had claimed— that when exploring his feeling of selfhood, he always landed “on some particular perception or other” but could never catch himself “at any time without a percepton, and never can observe anything but the perception”— was simply not true.33 Because for Hume to even report this feeling he had to perceive something in addition to the immediate perceptions, namely, the very flow of time that allowed them to be distinct in the first place. And to recognize time passing is necessarily to recognize that you are embedded in the perception.

Hence what Kant wrote in his answer to Hamann, ten years in the making. To recollect perfectly eradicates the recollection, just as to perceive perfectly eradicates the perception. For the one who recalls or perceives must recognize him or herself along with the memory or perception for the memory or impression to exist at all. If everything we learn about the world flows directly into us from utterly distinct bits of code, as the rationalists thought, or if everything we learn remains nothing but subjective, unconnected impressions, as Hume believed— it comes down to exactly the same thing. With no self to distinguish itself, no self to bridge two disparate moments in space-time, there is simply no one there to feel irritated at the inadequacy of “dog.” No experience whatsoever is possible.

Here is how Kant put it in his Critique of Pure Reason. Whatever we think or perceive can register as a thought or perception only if it causes a change in us, a “modification of the mind.” But these changes would not register at all if we did not connect them across time, “for as contained in one moment no representation can ever be anything other than absolute unity.”34 As contained in one moment. Think of experiencing a flow of events as a bit like watching a film. For something to be happening at all, the viewer makes a connection between each frame of the film, spanning the small differences so as to create the experience of movement. But if there is a completely new viewer for every frame, with no relation at all to the prior or subsequent frame, then all that remains is an absolute unity. But such a unity, which is exactly what Funes and Shereshevsky and Hume claimed they could experience, utterly negates perceiving anything at all, since all perception requires bridging impressions over time. In other words, it requires exactly what a truly perfect memory, a truly perfect perception, or a truly perfect observation absolutely denies: overlooking minor differences enough to be a self, a unity spanning distinct moments in time.

"The Rigor of Angels: Kant, Heisenberg, Borges, and the Ultimate Nature of Reality."

Sheer change and difference wouldn't really be "change." If one thing is completely discrete from another, if there is no linkage or similarity and relation, then, rather than becoming, you just have sui generis, unrelated things (perhaps popping in and out of existence?). This isn't becoming, but rather a strobe light of unrelated beings. So, leaving aside the difficulty that the past seems to dictate the future, that things seem to have causes, or the difficulties with contingent being "just happening, for no reason at all," it seems hard for me to see how there could be any sort of "sheer becoming." All things that exist are similar in that they exist. If we had "different sorts of unrelated existence," "sui generis types of being," they wouldn't have any relevance for each other. In unrelated moments, we wouldn't have change, just unrelated existence and non-existence.

Now, there is a conceptual priority vis-á-vis difference, and this is important to keep in focus. It's one of the great findings of information theory. But information theory deals with "what something is," and not "that it is," essence but not existence. It skips the former. We can see this in the fact that a perfect set of instructions to duplicate any physical system would not, in fact, be that system. A perfect duplicator, call it Leplace's Printer, needs both instructions and prior existent materials. Information assumes some prior distribution, even if only an uninformed prior, and some recipient. Arguably, this makes it intrinsically triadic (as the advocates of dyadic mechanism wont to point out as a deficit, taking this to mean it is in some way subjective and thence illusory.

However, for those who inherited some of the empiricist modes of thought, the order of knowing has become the order of being, and the priority of difference in discernment is taken to be identical with an ontic priority. I would disagree, for anything to be different it must first exist and be something, "this" or "that," and not nothing in particular. Act follows on being. And in any metaphysics of participation, this linkage is even clearer. The conceptual priority of difference to discernible essence is important, it just isn't an absolute ontic priority. Indeed, the order of knowing and the order of being are, in general, mirror images of one another, reversing the order of each. -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding being

Sort of like the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis for philosophy? It's an interesting though. However, it seems to me like Sapir-Whorf has fallen into ill repute in its stronger forms and the empirical support mustered for its weaker forms is, from what I can tell, is quite modest. Certainly, a lot of people have wanted it to be true, and I can see why, as it would suggest that merely speaking differently would open up all sorts of new horizons, but I am a bit skeptical. At least, prima facie, I would think that language is flexible enough to allow for either development in thought. English has being as a noun and verb, and Latin has ens/esse.

For instance, Indo-European languages have produced plenty of process/relational metaphysics. I think that critiques of the "metaphysics of presence" have often themselves painted too much with a monochrome brush (a sort of static presence itself maybe?). Certainly, there is Parmenides, Plato's forms, or Brahman as an ultimate and unchanging reality, but there has also been Heraclitus, Nagarjuna, and countless expositions on the Holy Trinity as fundamentally relational (self-giving love), living activity (or Brahman as activity). Aristotle sometimes gets lumped in as a key purveyor of "static being" or "substance metaphysics," but, were I forced to lump him into either category, I'd probably place him on the "process metaphysics" side. Hegel would be another example.

Not that there isn't a real issue here, although I would diagnose the problem more as two sorts of tendencies stemming from the Problem of the One and the Many. I think it's fair to say that, on average, and particularly since the Enlightenment (or maybe the Reformation), Western thought has tended too much towards the One (toward Parmenides). It has, at times however, lurched into excesses in the other direction. But I see the story as more about an attempt to chart a path between Scylla and Charybdis, rather than Western (and Indian?) thought having remained firmly in the clutches of one or the other. Plato's forms themselves were an attempt to chart a sort of via media here, and Aristotle is largely following his teacher's lead, but showing how the principles of his psychology can be expanded to an explanation of physics, i.e., "being qua changing."

For instance, the fullness of life and understanding attributed to God in much of the "Neoplatonic" tradition (across Pagan, Islamic, Jewish, and Christian thought), God as pure act, strikes me as something that cautions against any conception that is too "static." I'm reminded here of Derrida's "Plato's Pharmacy," which is focused on the ol' "problem of presence." However, I recall thinking that Derrida might be a bit off base in contrasting speech/writing here. In the Phaedrus at around 275a-276d, Plato is pretty clear that his claims about the insufficiency of writing have more to do with the lack of an intellect that knows what is said, and in the context of his overall metaphysics this reveals itself to be more about the insufficiency of finite things, which are more or less just bundles of external causes, and so not intelligible in themselves (being always referred to something else). The point is, as with Saint Augustine's "inner word," participation in Logos. Yet I'd hesitate to call this static. In a way it has to be most alive, lacking nothing. For Augustine and later thinkers in his tradition, it couldn't be a being, or even, univocally, "being," but was "beyond being" (or being/becoming). Dionysius says something on this to the effect of "It is false to say that God exists, but also false to say that God does not exist. But of the two, it is more false to say that God does not exist." -

The Origins and Evolution of Anthropological Concepts in Christianity

Not to add more wrinkles, but in his Orthodox Psychotherapy, Hierotheos Vlachos argues that soul (psyche) is said in two ways in Scripture, as the life of the entire man (including the body) and as our spiritual essence as spiritual beings. He draws on Saint Gregory Palamas here to help make the distinction, likening the spiritual essence of man (one use of soul) to our/God's essence, and the broader usage of soul to refer to our whole life to our/God's energies. That is, the life of the body is the actuality of our soul as a spiritual essence. I am pretty sure I have seen similar distinctions in other places, and made by Catholics (although some Catholics lean more towards a greater separation of body and soul).

As to the churches, that's an interesting comparison. The difficulty for me is that Orthodox Churches are quite rare where I live. I travel pretty far to go to mine and most of the services I attend are at a "mission" that holds its services in a Lutheran Church.

I'd tend to agree that, of the Orthodox Churches I've been to, they seem to do more the capture the idea of the liturgy as taking place outside of time, in the eternal throne room of Revelation, with the whole communion of the saints. And yet, Pope Benedict was writing about this same thing not long before he became pope.

I think it might partly be merely a difference in membership though. Orthodox Churches are rare here, so they are either large or attached to monasteries. Catholic churches are everywhere. I have 5 within ten minutes of me and I live in a rural town with one stoplight. In expanding they have often taken over buildings used by Protestants, and so their aesthetic style is sort of contained by the building they started with. Vatican II was followed by a pretty significant period of iconoclasm it seems as well, along with an experiment with new styles (like the lovely Chapel of the Sun in Sedona Arizona). So, some Catholic churches are very bare, and then some (like the largest near me), do more to incorporate the famous Gothic style (which also took so much from Dionysius the Areopagite in its own way).

The biggest difference in emphasis for me is the centrality of the crucified Christ versus Mary at the front, and the presence of Christ as almighty creator in the dome. This to me is emblematic of a relatively greater focus on the Crucifixion and Atonement, versus the Incarnation. The Stations of the Cross are another example of this. Both of these place an emphasis on the body of Christ, but in different ways.

But, I will here draw an even starker contrast, which are the entirely functional Evangelical church buildings I've been too, which often feel like, or are even built into, strip mall type settings. Here, full coffee shops and donuts are often out front and food is carried into the sanctuary for the service, a far cry from mandatory fasting before the Eucharist.

This might be the best representation of a tradition that attempts to wholly look beyond the physical. It also tends to look beyond the formal, with little formal structure of the "service" (which is explicitly no longer a "liturgy"). Often, the worship service is performed by a band, rather than hymns and Psalms being chanted by the church. Indeed, formal structure is generally seen as inhibiting authenticity, and so too for any physical formality. The idea of the Eucharist as wholly symbolic and mental would seem to go right along with this. What is important is what is going on "inside," not the bread and wine (or now often grape juice), if it even makes an appearance (it often doesn't most weeks).

When I think about this, it seems very strange. The tradition that tends most towards literalism ends up also paying the least attention to concrete instantiations of the faith. And yet maybe it makes sense in a certain way. In the Anglophone context, ethics if often thought to be the main substance of the Church. But this is often paired with a view of ethics as sitting entirely outside nature as command. Likewise, a view of God as primarily will, and of notions of nature as a potentially nefarious limit on that will, would tend towards demoting nature in a way.

So it makes sense in a way, but it still seems to me that fundamentalism and an attempt to excise the influence of Greek thought from the faith might make equally as much sense when paired with an extremely concrete practice, e.g., one that tries to life out the concreteness of the old covenant (maybe Messianic Judaism is sort of an example?)

I will say that in terms of sermons I've heard these do tend to suggest the strongest mind/body and nature/supernatural dualism, even though, at the same time, the general rejection of asceticism, monasticism, celibacy, etc. seem to in some ways go in the other direction. It is a tradition that does not focus on the physical, but precisely because it focuses on the physical so little, it has little time for a sort of Platonic unease with the body. -

The Problem of Affirmation of Life

If you liked Nietzsche I would give Dostoevsky a try. In a lot of ways they have very similar biographies and personalities. Nietzsche was a tremendous fan of Dostoevsky as well. And yet in key ways they could hardly be more different.

Notes from the Underground is a good starting point because it is quite short and less meandering than a lot of his work. Nietzsche was also a huge admirer of that work in particular, although one might suspect on this point that he wasn't totally getting what Dostoevsky was trying to lay down, since, for all their similarities, they come to radically different conclusions about ethics, suffering, happiness, and Christianity. The Brothers Karamazov is his great classic, but it's also a pretty mammoth tome.

Now, understanding the tradition Dostoevsky is coming out of is much harder. I cannot think of a good work that sums it up. It's a sort of project to digest for sure. The book Orthodox Psychotherapy is a good one though.

Another classic that looks at suffering and happiness is Boethius Consolation of Philosophy. It's a charming book that blends together the "first medicine" of Stoicism, which paves the way for the "second medicine," the Platonic ascent as informed by Aristotle, Plotinus, Saint Augustine, etc. -

The Origins and Evolution of Anthropological Concepts in Christianity

Indeed, the idea of resurrection was not new for that time. However, according to my information, it was not the central teaching for all of Judaism as a whole

This is what I understand too, broadly speaking. Although there seems to have been a fair amount of diversity. However, the Pharisees, who play an outsized role in the NT, did believe in a resurrection, as did the Essenes. Unfortunately, the exact religious context is sort of murky. It's sheer luck (or Providential will perhaps) that the Dead Sea Scrolls were found and we have come to know as much as we do about the general context.

I have seen the claim though that the resurrection was more central to Judaism in the late Second Temple period, and that it is rather Christianity, and Judaism increasingly being defined in opposition to it, that led to a pivot away from the theology. More mainstream, it is generally taken that this is why the Jews moved away from using the Septuagint, and the Septuagint has more texts that are friendly to a theology of resurrection.

In conclusion, I would like to present you with an idea from the Orthodox confession about holism. Holism is a view of man as a single, inseparable, spiritual-mental-physical personality. There is no opposition of spirit and matter, but their interpenetration and interaction. As light permeates the air, so the soul permeates the body, forming a single whole. Unfortunately, I do not know for what reason, but none of the Orthodox priests I met mentioned this topic until I became familiar with it myself. Can you share with me about this area if you have knowledge on this topic?

Sounds familiar. The Eastern Fathers and later thinkers stay closer to the formulation of the tripartite soul (appetitive, spirited, rational), whereas this psychology evolved in the West into the idea of the concupiscible appetites, irascible appetites, and rational appetites (will/intellect). I do think this tended to do more to locate the "lower appetites" in the body as set against an immaterial component. Whereas the nous remains more defuse. I do recall this being a tension Saint Gregory Palamas addresses in the Triads, where he affirms a role for the body in the contemplative ascent as against Barlam's "Western" view. However, the more famous high scholastic voices like Saint Bonaventure and Saint Thomas are more nuanced, and I think they can be read as often saying something compatible, but with a different emphases (although the beatific vision as being primarily intellectual could be read in starker terms. I think the more developed Eastern theology of the Transfiguration marks a difference in emphasis here too. -

The End of Woke

I find this assertion strange because the annals of Woke protest letters/debates are full of assertions of an expansive moral and epistemic relativism/anti-realism.

Consider, for example, “thou shalt not be a white supremacist.” In 2017, the president of Pamona College (Claremont, California), David Oxtoby, wrote an email to the entire campus in response to protesters who had shut down a speech intended to be given by Black Lives Matter critic Heather Mac Donald. In the email, Oxtoby expressed his disapproval of the shutdown, arguing that it conflicted with the mission of Pamona College, which is “the discovery of truth” and “the collaborative development of knowledge.”

[The students wrote an open response letter...]

“The idea that there is a single truth — ‘the Truth’ — is a construct of the Euro-West that is deeply rooted in the Enlightenment, which was a movement that also described Black and Brown people as both subhuman and impervious to pain,” the students’ letter stated, according to The Claremont Independent. “This construction is a myth and white supremacy, imperialism, colonization, capitalism, and the United States of America are all of its progeny.”

“The idea that truth is an entity for which we must search, in matters that endanger our abilities to exist in open spaces, is an attempt to silence oppressed peoples,” it continues.

https://www.nationalreview.com/2017/04/pomona-students-truth-myth-and-white-supremacy/ -

The End of Woke

How is this not an argument against the very possibility of totalitarianism tout court, regardless of the ideology consumed by its practitioners? And yet, totalitarianism does exist, and it does not seem impossible that someone who has digested Deleuze or Nietzsche could practice it.

Likewise, your former objection would seem be an objection to the possibility of self-interested behavior tout court. Yet both self-interest as a motivation, and relative selflessness, also seem to exist; there is a meaningful distinction between them. It's the same with rejections of the possibility of weakness of will or the existence of norms.

Might I suggest that if an ideology demands the denial of the very possibility of many of the more obvious features of human life—if it demands that the ideology be affirmed over the obvious—this is itself a sign of potential totalitarianism?

I have nothing against an attempt to find a unifying principle that can be found throughout the appetites, be it "union with the good" or the search for "actuality" or "intelligibility" (arguably all three being the same thing). However, difficulties arise when it is denied that this unifying principle is realized analogously across different appetites, i.e., when all desire and appetition is reduced to a univocal understanding of some term, be it "utility" or "intelligibility." This is, IMO, perhaps the cardinal sin of liberalism, and one its descendants have tended to take on board. An anthropology that is so thin as to make no differentiation between epithumia (e.g., hunger), thymos (e.g., offended honor), and logos (e.g., the desire to "be a good person") is too thin to explain human history, politics, or ethics.

Second, the move to endorse a sort of amoral, disinterested analysis is itself the imposition of a value judgement. I get the basic idea. If we get rid of the moral valence, the blame, and adopt the dispassioned stance of the buffered self, we will avoid getting angry at people (anger is here negative), and thus avoid making the "mistake" of judging people or acts in moral terms.

The problem here is twofold. First, the supposition that getting rid of blame or moral judgement is going to "improve politics" or our "political judgement" seems problematic. On the Stoic view that the passions are simply bad, or at least "bad for reason," it makes sense. Yet the Stoics are wrong here. Rather, what is ideal is to experience just anger over what warrants anger, and likewise to experience just admiration of what warrants admiration. The passions are not a problem any more than the appetites are; only their improper orientation is problematic. The move to exclude morality from political thought is akin to amputating one's hand because one hasn't trained it to preform properly.

A view that advocates the reduction of the human being to a raft of social forces, flows, knots of language, etc., might very well be palliative in that it reduces inappropriate or overwrought anger. However, it can just as easily support callous indifference to suffering and vice. Such a reductionist account also destroys our notions of merit and goodness. It removes the beauty from history and ethical acts. One can certainly study a raft of social forces. One might even try to tinker with it to produce "choice-worthy outcomes." But does one resist serious temptation or suffer hardship for the sake of eddies of social force? Does one stand upon the ramparts in battle and risk maiming and death to save "flows," "sequences," and "concatenations?"

The same problem one finds in liberalism repeats itself here. Civilization requires the pursuit of arduous goods. It requires selfless leadership, a willingness to endure significant hardship and resist extreme temptation even in times of peace, and heroism in times of war. A denial of thymos and logos leaves no ground for such pursuits. A view that dissolves the subject, and thus merit, aside from being metaphysically and psychologically flawed, also fails as being properly pragmatic for society (let alone aesthetically pleasing).

We might suppose then that mercy, clementia, is wanted more than amoralism. That is, "men with great hearts," rather than C.S. Lewis's "men without chests."

The second issue is that such appeals generally tend to be illusory. Dispassion, in the Stoic sense, might be more or less established in individuals, but apatheia is not apathy. It doesn't dispense with values. Were we to dispense with them, there would be no proper standard by which to measure anything. Rather, what one cares to elevate tends to end up being left outside the "bracket" and is raised up on account of all other contenders having been dispatched.

The idea of man as eddies of social force (granted not as fully matured) is exactly the sort of thing I think Dostoevsky argues against to great effect throughout Crime and Punishment. Raskolnikov is only aligned to his natural compassion when he is forgetful of this "new understanding." -

The Christian narrative

Well, it's complex. Saint Thomas cites Saint Augustine more than any other thinker (10,000+ times!) and Augustine suggests we can see the divine image (including the Trinity) by looking within. The second half of his book on the Trinity is a sort of phenomenological dive into the triads that fill the very conditions of experience. Likewise, there was a long tradition of seeing God, and the Trinity in created things (Saint Bonaventure is a great example here). Thomas isn't really at odds with these, but he doesn't think you can demonstrate the Trinity.

However, if one takes the view that all relations are inherently triadic and that the semiotic triad is the precondition for anything to be meaningfully anything at all, I think it's possible to construct a sort of transcendental argument towards the Trinity. -

The End of Woke

Totalitarianism has to lock in, to totalize something. Doesnt it totalize a particular value system? If one says that a radical relativist acquiesces to totalitarianism

because they sanction an ‘anything goes’ approach to values and ethics, how are the systems that are ‘ going’ their own way treated by these radical relativists? Doesn’t anything totalitarian have to get going and then ossify into a self-perpetuating structure? Isnt the indefinite temporal repetition of the same system or structure a necessary condition for calling anything totalitarian? If so, then an ‘anything goes’ relativist would have to embrace the proliferation of an unlimited multiplicity of diverse and incompatible totalitarian systems.

Relativism, even in its extreme forms, does not need to imply that we prefer or will all possible eventualities equally. Indeed, extreme forms of relativism are most coherent (perhaps only coherent) in the context of volanturism. "Anything goes," and "all assertion involves violence" does not imply "so we ought do nothing, ought not tip the scales in any direction." It can suggest this (e.g., ancient skepticism) but it need not. Any such endorsement of neutrality or "live and let live" would itself prove to be insubstantial, merely another assertion of one value over others. Thus, nothing precludes totalitarianism or recommends tolerance and pluralism.

As Hannah Arendt famously put it: "The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the dedicated communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction, true and false, no longer exists." Orwell riffs on a similar insight throughout 1984, and Soviet writers have gone into depth on how this was applied as praxis.

If so, then an ‘anything goes’ relativist would have to embrace the proliferation of an unlimited multiplicity of diverse and incompatible totalitarian systems.

Why? Are they committed to some sort of inviolable principle that leads from the truth of relativism to this sort of open-ended tolerance? I don't see why they would be.

To wit:

But all these are only preliminary conditions for his task; this task itself demands something else—it requires him TO CREATE VALUES. The philosophical workers, after the excellent pattern of Kant and Hegel, have to fix and formalize some great existing body of valuations—that is to say, former DETERMINATIONS OF VALUE, creations of value, which have become prevalent, and are for a time called "truths"—whether in the domain of the LOGICAL, the POLITICAL (moral), or the ARTISTIC. It is for these investigators to make whatever has happened and been esteemed hitherto, conspicuous, conceivable, intelligible, and manageable, to shorten everything long, even "time" itself, and to SUBJUGATE the entire past: an immense and wonderful task, in the carrying out of which all refined pride, all tenacious will, can surely find satisfaction. THE REAL PHILOSOPHERS, HOWEVER, ARE COMMANDERS AND LAW-GIVERS; they say: "Thus SHALL it be!" They determine first the Whither and the Why of mankind, and thereby set aside the previous labour of all philosophical workers, and all subjugators of the past—they grasp at the future with a creative hand, and whatever is and was, becomes for them thereby a means, an instrument, and a hammer. Their "knowing" is CREATING, their creating is a law-giving, their will to truth is—WILL TO POWER.—Are there at present such philosophers? Have there ever been such philosophers? MUST there not be such philosophers some day? ...

Nietzsche - Beyond Good and Evil - Ch. 5 We Scholars - Section 211

In NEW PHILOSOPHERS—there is no other alternative: in minds strong and original enough to initiate opposite estimates of value, to transvalue and invert "eternal valuations"; in forerunners, in men of the future, who in the present shall fix the constraints and fasten the knots which will compel millenniums to take NEW paths. To teach man the future of humanity as his WILL, as depending on human will, and to make preparation for vast hazardous enterprises and collective attempts in rearing and educating, in order thereby to put an end to the frightful rule of folly and chance which has hitherto gone by the name of "history" (the folly of the "greatest number" is only its last form)—for that purpose a new type of philosopher and commander will some time or other be needed, at the very idea of which everything that has existed in the way of occult, terrible, and benevolent beings might look pale and dwarfed.

Section 203

Or also:

"What is good?—Whatever augments the feeling of power, the will to power, power itself, in man.

What is evil?—Whatever springs from weakness.

What is happiness?—The feeling that power increases—that resistance is overcome.

Not contentment, but more power; not peace at any price, but war; not virtue, but efficiency (virtue in the Renaissance sense, virtu, virtue free of moral acid).

The weak and the botched shall perish: first principle of our charity. And one should help them to it.

What is more harmful than any vice?—Practical sympathy for the botched and the weak—Christianity."

- Antichrist 2 -

The End of Woke

I still think it is worth considering why such pluralist sources such as CT and post-modernism, vastly lead to the same progressive conclusions. If it was even 59% it wouldn’t be a good question, but it has to be more like 90% or more. Something is off about the PM and CT methodologies, where all of these more relativist/ pluralist thinking structures, like a funnel, yield the same societal conclusions.

(The pluralist/relativist baseline is why they avoid any sense of self-awareness of their own brand of facism and absolutism that can result when they have power and seek to impose these vastly uniform progressive conclusions.)

Prima facie, it didn't have to lead that way. Many of the early adopters of Nietzsche who rescued him from obscurity leaned to the right. I actually think systems of power, decentralized incentive structures, cultural biases, the systems of power inherit in careerism, and an oversaturated job market, etc. are quite good explanations here (which supports the original position). It's also worth noting that in the US context Christianity had held up remarkably well in comparison to the rest of the West until quite recently. Hence, it could remain a sort of "mainstream" custom to rebel against (even for foreigners, due to the outsized US influence), and our culture has a marked preference for iconoclasm. Anti-realism can suggest the embrace of custom on aesthetic or other grounds, but this line didn't suggest itself.

However, note that the emergence of a right wing (post-Christian) post-modernism skews quite recent. I don't think this is incidental. In bourgeois coastal society, and particularly in academia, traditionalism finally became properly transgressive. (I happened to be reading Origen and Saint Maximus at the same time as Byung-Chul Han and Mark Fisher and it struck me that the former two were by far the more radical and transgressive in the current context, and not because of a traditionalist absolutism, but because of their radical optimism, aesthetic outlook, asceticism, and total lack of irony).

At the same time, a new post-Christian branch of the GOP coalition grew in size and influence, meaning such theorists would actually have allies and support to pull on. -

The End of Woke

Concepts like status, self-interest, power and control can inform diametrically opposed positions depending on how the subjectivity, or ‘self’, they refer back to is understood. If we start from the self as homo economicus, a Hobbesian figure the attainment of whose desires need not have any connection with the desires of others, then we either settle for a Darwinian Capitalism or find a way to insert into this self an ethical conscience which we will not always be able to depend on. If instead we see the self not as an entity but as a process of unification, self as self-consistency, and desire as oriented toward anticipatory sense-making ( We don’t desire things, we desire coherence of intelligibility), then there is no i weren’t slot between the needs of my own ‘self’ and the needs of other selves. The unethical is then not a result of bad conscience but a failure of intelligibility. The unassimilable Other is found wherever injustice occurs (slavery, genocide).

Sure, you could describe it lots of ways. You could also think of it as a system of (perverse) incentives.

I have argued that the doctrine of nihilistic will to power is not a plausible explanation for the moral absolutism characteristic of wokism. Such absolutism can only justify itself on the basis of a realist-idealist grounding of some sort, which happens to be the stock and traded of Critical theory. I suggested in another post that the most noxious totalitarian tendencies of wokism can be moderated or even eliminated as more activists discover Habermas’s hermeneutical, communicative brand of Critical Theory and begin to leave behind the violently oppositional language of folks like Adorno, Fanon and Gramsci.

I'd place the main influence for the appearance of absolutism within the earlier activist traditions, which were firmly embedded in Christian and Islamic contexts, and made use of prophetic language. However, is "moral absolutism" really characteristic of Wokism?

I know some pretty Woke folk, and I cannot think of a single one who would endorse moral absolutism if asked. Rather, you'd get epistemic relativism and meta-ethical anti-realism. I happened to be in an ethics class during the height of the Great Awokening and this was precisely my experience.

Generally, any absolutism is held to as a sort of performative contradiction; the absolutism of Woke is primarily performative and volanturistic (indeed, both absolutism and negativity towards performative contradiction seem like the sort of things that are likely to get written off as a sort of cis-het-white-male-Western-etc. normativity, merely an assertion to be met with counter assertion, or even a sort of epistemic violence that tries to enforce a logical binary on expression).