-

The irreducibility of phenomenal experiences does not refute physicalism.

But I am talking about the information contents of the actual image, you are talking about features of the physical object the image has been projected on. I can produce the same image on different paper or have it on a digital screen and identify the contents of the image; those contents are not directly related to the physical composition of a photograph you can hold in your hand and cannot be reduced to it, which is the main point.

Yes, it's true that that image is not totally independent of other factors; after all, the type of camera and resolution etc will have an effect on the image but these largely still come from the same interactions during the photo-taking process by which the image of Everest was stored - it is still information of the image which is independent of the physical medium an image is projected on and so cannot be reduced to it.

I don't disagree that there is a useful distinction to be made between the "image" and the physical photograph. We can think of the image as the "Shannon Entropy," a collection of variable discrete differences that is substrate independent.

But physicalism says that the physical subservienes on any such information. That is, all representation is representation only in virtue of the physical properties of the system that holds the representation. Thus, while we can abstract the picture from the photograph, and we can say that there are isomorphisms between different copies of the same image, these are causally irrelevant. All cause can be explained in purely physical terms, the causal closure principle.

So what you're describing seems to be more an argument against physicalism than a way to save physicalism. Physicalism without causal closure and superveniance doesn't seem to be physicalism. Physicalism says that everything that can be known about seeing red is physical. There is nothing else. Perhaps experiencing red is a different experience than knowing "how red is experienced." This is fine, but it's going to lead you to physicalism with type or predicate dualism (which may or may not be physicalism depending on who you ask).

Now you do have scientific theories where information is essential, "it from bit," views in physics, Deacon's "absential phenomena," which are born of what "is not physically present," etc. But generally information based ontologies, at least those that say that information is ontologically primitive, are taken to be "immateriality," and not physicalism.

If physicalism isn't going to fall to Hemple's dilemma and define itself as "just whatever currently has evidential support," it seems like it has to pick a hill to die on, and superveniance is the most obvious hill.

To be fair, I think similar sorts of problems show up for idealism. I am inclined to think that the problem might be substance metaphysics writ large, with both physicalism and idealism making the cardinal error of following Parmenides in thinking of static being-as-substance, instead of Parmenides being-as-flux-shaped-through-logos. Maybe these even helps get at cosmological issues because, while stabilities of matter have begining and end, the Logos is necessarily without beginning or end, as cause and effect is the ground from which before and after can even exist (for a bit of a non-sequitor). -

Is Philosophy still Relevant?From Karl Barth's "Evangelical Theology: An Introduction," but much the same could be said for philosophy.

Ever since the fading of its illusory splendor as a leading academic power during the Middle Ages, theology has taken too many pains to justify its own existence. It has tried too hard, especially in the nineteenth century, to secure for itself at least a small but honorable place in the throne room of general science. This attempt at self-justification has been no help to its own work. The fact is that it has made theology, to a great extent, hesitant and halfhearted; moreover, this uncertainty has earned theology no more respect for its achievements than a very modest tip of the hat. Strange to say, the surrounding world only recommenced to take notice of theology in earnest (though rather morosely) when it again undertook to consider and concentrate more strongly upon its own affairs. Theology had first to renounce all apologetics or external guarantees of its position within the environment of other sciences, for it will always stand on the firmest ground when it simply acts according to the law of its own being. It will follow this law without lengthy explanations and

excuses. Even today, theology has by no means done this vigorously and untiringly enough. On the other hand, what are "culture’' and '‘general science,” after all? Have these concepts not become strangely unstable within the last fifty years ? At any rate, are they not too beset by problems for us at present to be "guided by them? All the same, we should certainly not disdain reflecting on what the rest of the academic world actually must think of theology. It is worth considering the place of theology within the university; discussion may be held about the reason and justification for locating this modest, free, critical, and happy science suis generis in such an environment.

Philosophy seems like it should have a special place in the world of "interdisciplinary studies." Philosophers of the sciences are aptly suited for translating between different paradigms and fields, looking at the coherence of new explanations of the world.

The widespread use and abuse of the term "information," across the sciences, from physics to biology to economics, seems like a perfect place for philosophy to interact with cutting edge paradigm shifts that are important to the project of the academy writ large for example. Are these people really using the term the same way? Is there a coherent single entity the term "information," points to across these fields?

Instead, philosophy has been one of the chief advocates for rigorous siloing of specialities. "Thou shalt not speak of what one lacks a credential in!" Notably, scientists themselves pay very little attention to this sort of thing (Pinker and Rovelli have written what are essentially philosophy books, more modestly, Deacon goes a good way out of the purview of biology in his theorizing; all ambitions theorizing requires tearing down silos). It seems somewhat motivated by the fear that, if silos are violated, then scientists, with far more public cache, will heap scorn upon philosophical projects. But the reason philosophers have so little cache to begin with is precisely because they embarked on a project to exorcise themselves from relevance in the 20th century.

To my mind, credentialism itself is a problem. A masters degree lasts two years. It doesn't make one a master of anything. A PhD is still only 4-6 years of study. Academic careers span decades and people can master new material that turns out to be relevant to their projects. If someone spouts off nonsense the scientific and philosophical community has no problem correcting them and heaping scorn upon them; you already see this in the vitriol slung around over challenges to the Central Dogma within biology itself.

Not to mention that the worst offenders of speaking about things they don't understand never abide by these rules in the first place, so by ceding the interdisciplinary, big picture metaphysics field, it just gets filled by those with the biggest egos, and/or those who think Lizard People rule the planet.

Plus, sometimes extremely deflationary views of everything start to seem as merely defense mechanisms:

Meanwhile, if the fear of falling into error introduces an element of distrust into science, which without any scruples of that sort goes to work and actually does know, it is not easy to understand why, conversely, a distrust should not be placed in this very distrust, and why we should not take care lest the fear of error is not just the initial error. As a matter of fact, this fear presupposes something, indeed a great deal, as truth, and supports its scruples and consequences on what should itself be examined beforehand to see whether it is truth... a position which, while calling itself fear of error, makes itself known rather as fear of the truth. -

What is Logic?

Do naturalists really speak this way when they are being rigorous and are not engaging in loose and poetic metaphor?

Yes? We speak of the "law like behavior," of the universe and it is considered perfectly legitimate to rule out a scientific explanation if it suggests that nature is somehow preforming a contradiction. Work in quantum foundations for instance is largely about how to explain puzzling phenomena in a manner that is consistent and doesn't admit contradictions.

When there are references to the "logic of natural selection," vis-á-vis evolutionary game theory we mean to say that logic of our simplified models "maps onto" nature, that there are isomorphisms there, not that the logic is something "we create in order in our mind to make an orderless process out in the world comprehendible." In the physicalist, naturalist view, our ability to "make sense," is after all, the product of nature, in no way suis generis. This is why biology admits both "functional," and "adaptive," explanations as distinct types of causal explanations in its field.

I've read enough biology and philosophy of biology to feel fairly confident in saying that talk about the logic of selection is about morphism between our model and how nature is in-and-of-itself. Physics is less clear on this. QBism for example punts on such an assertion, but many theories in quantum foundations are saying that our mathematical formalism is mapping to nature, that nature embodies this formalism.

The concept of Logos is problematic not only for its spiritual connotations and connotations of intentionality (the idea that nature is not teleological is a bit of a dogma in naturalism today) but even moreso because it implies that any order in nature is enforced externally, say by eternal "laws of nature," that exist outside nature. This isn't popular due to Hume's "problem of induction" and Kripke's essentialist response. We generally now think that nature has the properties of order that it does because of what nature is, or because of what natural entities are. That is, the "logic" of state progression in nature is intrinsic, not extrinsic. But this in no way means that the order doesn't exist outside the mind, it simply means that such an order is inherit to nature because of what nature is.

Any ability we have to recognize such patterns and develop logical systems is itself the result of natural causal interactions. Further, while logical systems have "contrived, mental sources," writ large natural language, and the logical explanations it allows, is an evolved capability in hominids that appears to have likely predated homo sapiens. Further, language itself, and maybe even the sciences arguably appear to advance due to the same sorts of dynamical processes that lead to biological evolution. This isn't particularly surprising given how the same mathematics can describe such a wide range of phenomena in complexity studies; the world seems to display a sort of multiscale fractal recurrence in causal patterns. -

The Identity of Indiscernibles and the Principle of Irrelevance

There is the debate over whether there are properties without (active) observation.

The Principle of Indiscernability doesn't look at that. It looks at the question of: "is it worth giving any consideration to propositions whose truth values will in principle will always seem coidentical."

For example: "a noumenal world exists even when no phenomena exists," is a statement about a state of affairs. But, whether this state of affairs obtains or not is always and forever indiscernible for all observers. This being the case, why bother considering it?

Moreover, if you do consider it, what stops us from considering an infinite number of such in principle forever unobservable entities?

So, not quite the same debate. -

The Identity of Indiscernibles and the Principle of Irrelevance

I think that this principle can only be upheld by making an unjustifiable assumption about the nature of observers. You are saying that if X is indiscernible from Y, for all observers, then X=Y.

The first problem is the problem of induction. No matter how many observers perceive X as identical to Y, we will never know whether or not the next one will. So X=Y can never be proven.

Yes, but the argument is about things that cannot be observed by definition. For example, suppose we posit a new fundemental particle, the nullon, that interacts with nothing, nada, no way to see it through any interactions, by definition. This would be an example that by definition cannot be observed.

The noumena that does not generate phenomena is another such example. How exactly could there be an observer that observes without any phenomenal experience? How can "what can only be sans an observer," possibly be observed by any observer?

I think your point is a good one. It's about the limits of induction, but it doesn't deal with things that are shown to be unobservable by deduction. The question then is: should we consider such things at all?

This has implications for realism as well. If we somehow "grasp" abstract entities like propositions, then we can say they exist in some way. But if such entities are only known through their instantiations, and everything we can know about them comes solely through their phenomenal instantiations, then it seems like the existence of abstract entities as abstract entities (as opposed to concrete exemplars) is coidentical with all observers, always and forever, with such abstract entities not actually existing. Their being and not being are indiscernible. -

Is touching possible?

As opposed to how well philosophy doing right now at being relevant? Every time I go into a book store I check out the philosophy section and it invariably is tiny and has just a few copies of books by the same 4-6 authors. Philosophy has become so scared of error that it's afraid to be relevant. Sometimes I even think the arcane vocabulary becomes a hiding mechanism.

BTW, these are the best sellers in "philosophy/metaphysics"

anonymous photo

Refusing to enter the field for fear of looking silly seems to result in:

A. People reading one of six or so "great names," and taking them as gospel, or not enjoying them and deciding philosophy is nonsense or;

B. People curious about metaphysics reading about how we're in the Lizard People's simulation and the this knowledge is what they killed Princess Diana/Sophia/Wisdom over (yes, Di was an Aeon and the British royal family are Lizard People Archons, except from Prince Harry who was converted over to being an Aeon by the Princess Meg Aeon).

IDK, people might get more value if the field wasn't left empty. -

Is touching possible?

I think those are all good points. Speculation is pragmatic, we get joy (utility for us welfare economists) simply from feeling that we understand the world better. It's just that this sort of pragmatic value is less attached to concrete goods in the world or actions (unless we consider "understanding" to be an action).

What I wanted to get at is that "is touch real?", "do you see the same blue as me? or "do dogs or worms have minds and do other people have minds?" while being the purview of philosophers, aren't only the concerns of philosophers. I remember thinking of solipsism back in elementary school. So, we shouldn't dismiss those sorts of problems on the grounds that we can sufficiently explain touch naively for your standard use cases. If people were satisfied with naive answers, they wouldn't ask these sorts of questions in the first place.

Now, if they don't ask those sorts of questions, I'd agree that there is no point informing them about electron clouds, fields, etc. They have better things to do lol. -

Is touching possible?

Oh for sure. But when someone say's "does touch really exist," I assume they mean: "from the standpoint of fundemental physics or metaphysics," simply because the question is silly in any other context.

This is an example where the understanding wrought by the linguistic turn seems to backfire. "Take language the way it is commonly used," is all well and good advice in some cases, but it missteps when it assumes that people don't ever think about metaphysics in their day to day lives. This just doesn't seem to be the case. Books on this sort of thing wouldn't sell millions of copies and churches wouldn't be packed each weekend if these sorts of questions only interested a few egg heads. In our ordinary, everyday lives we still sometimes ask deep metaphysical questions of this sort.

For example: you don't need to study any philosophy to see that:

A. Objects break down over time and things change; and then ask:

B. Is change or objects fundemental?

I'm of the mind that "prephilosophical intuitions," don't really exist. The oldest writing we have speaks to metaphysical concerns. A rough sketch of Plato's theory of forms is sketched in Memphite Theology near the dawn of written language capable of carrying such ideas.

"Do things really touch?" in the sort of question a middle schooler might ask, because they see that naive explanations are often partial, and are hoping for a greater level of clarity.

Pragmatics has to do with how the question is being asked. But sometimes we ask things from a purely speculative place. "Do you see the same type of red as me? i.e., questions of inverted qualia, are things I recall talking about in high school before ever picking up a philosophy book. To a certain extent, philosophers have caricatured "naive language," to fit it in a nice box so that "intractable" problems can be dismissed as "merely the delusions of us egg heads." But IMO, almost everyone has at least little egg head in them. -

The Complexities of Abortion

Since society does not value the life of a child enough to support it properly, it is the purest hypocrisy to place that burden on women. If society wants to take responsibility for children, then it should actually put its money where its self-righteous, hypocritical, moralising mouth is. Until society can properly protect the born, it has no business legislating for the unborn.

Right, and children are most labor intensive in the first three years and in the US at least the general provision of services is such that families are on their own, finding their own services, with no access to public schools until their kids are four or five years old. And of course, no paid leave for giving birth.

And yet we'll hear complaints about falling birth rates to no end... -

The Complexities of Abortion

I'm pro-choice and find that in the inviolability of our physical integrity. I choose what goes in and comes out of my body. Having others tell a woman she must carry to term just sounds like a violation in itself.

I'm pro-choice but I will play devil's advocate here.

1. Bodily autonomy isn't something we can uphold as an absolute if we want to have a functioning justice system. If Hannibal is a serial killer cannibal who has eaten all his neighbors, then most people would agree that we have a right to decide that Hannibal can't leave his prison cell, or that we even have the right to execute Hannibal. We have also told Hannibal what he can't put into his body, namely his neighbors. So, obviously bodily autonomy has its limits. Putting people in prison at the very least determines what can go into their bodies, and executing them determines what goes into and out of their bodies.

Most people agree with some limits on free speech, e.g., not being able to yell "fire" in a crowded theater. But this is also a limit on what is allowed to come out of one's body. The idea that the limits on state intervention on what goes into or out of people's body stops at said items being solid forms of matter seems pretty arbitrary. We can restrict sound waves in the form of "fire" from leaving one's body in some contexts to promote the safety of others but we can restrict a solid piece of matter from leaving because... it's solid? Not to mention that this would seem to preclude laws against public defecation, which no one wants.

This being the case, it's clear the state can say things about what is allowed to come out of your body. You can't take a dump on the subway because it is a health and safety risk for other people and ruins their experience of the subway. But this means that we indeed DO make rules about what can go in and out of people's bodies based on the safety of others, which is exactly the sort of argument made against abortion.

2. Conscription is a necessary evil for modern countries. Most people don't want to fight on modern battlefields and yet if no one fights you get stuff like the Nazis or Soviets despoiling your country and enslaving/starving the population. Because of this threat, we have conscription. That is, for the greater good, we allow the state to greatly constrict young men's autonomy.

Conscription forces constraints on what goes into one's body (only the rations you get), and moreover often results in getting things put into your body that you don't want (shrapnel) and things coming out that you don't want (your blood). But if the state can justify conscription for the greater good, which it seems it can in some contexts, then the preclusion on these sorts of restrictions doesn't seem absolute. -

Is touching possible?

Quite. There is a misguided tendency to take physics way outside of its purview.

Touch, for example, billiard balls touching and transferring kinetic energy, etc. is the bread and butter of physics. It's not that touch isn't the sort of thing physics should describe, it's that it isn't always useful to reduce things as far as possible. Actually, if there is strong emergence, it's counterproductive to try to define touch in terms of EM fields, but the question of emergence is an open one.

"Do things actually touch," really seems to be a question about weak versus strong emergence to some degree. If things don't touch in fundemental physics, and we think all physics is fully reducible to this sort of contactless description, then that provides us with a different sort of answer then in a world where we think:

A. Fundemental physics does involve contact.

B. There is strong emergence. -

Is touching possible?Maybe some sort of analogue of Mandelbrot's fractional dimensions is needed here? At a certain scale, two items seem to be touching, but zoom in or out and this can change.

North and South America appear to touch, until you zoom in very far to see the Panama Canal. Two humans holding hands appear to touch, but at a fine enough scale what you get is view where the borders of each human are poorly defined, and the primary "substance" of molecules don't touch, but rather repel each other based on charges.

Of course, a lot of us, myself included, probably have a skewed conception of touch based on the "empty atom model." In this model, the nucleus of an atom is comparably the size of a bee buzzing around a baseball stadium. Almost all the space "inside an atom," is empty, mostly occupied by an electron cloud, which is what does all the heavy lifting in explaining chemical reactions and touch.

But we also have to bear in mind the Pauli exclusion principle: the less massive the particle, the greater the delocalisation. Thus, a single electron cloud might engulf an entire large molecules, and it becomes more useful to picture how this cloud works by thinking of it as a sort of semisolid soup rather than as a bunch of incredibly tiny singular electrons in wild orbits, moving through mostly "empty space."

https://aeon.co/essays/why-the-empty-atom-picture-misunderstands-quantum-theory

If we take the "electron cloud as soup," picture, we can recover an intuitive picture of touch. We have touch when the clouds come into contact with one another. The problem is that sometimes this touch causes simply repulsion, but sometimes we get reactions that change the molecules and the shape of the clouds themselves. In a chemical reaction, the "touch" often results in both original objects disappearing and a new one forming.

But we still have points in favor of the fractal dimensionality view! Because if we keep shrinking down our view, the soup does indeed to resolve into a bunch of tiny particles flying in orbits in empty space. And at this scale, nothing touches. Instead, our stable electron particles shoot virtual particles at each other. But even these virtual "particles" don't actually "touch," because they are actually just perturbations in the same base field. Parts of a field touch of course, but only in the trivial sense that a field "touches itself."

Thus, it seems like the geometries we use to define objects and if they are in contact with one another undergoes a sort of kaleidoscopic fractal shift depending on how closely we look. Perhaps beneath the fields are strings that "touch," the jury is out.

IMO, this might just be showing the limits of an "object" and "substance," based metaphysics. After all, what are the boundaries of an object like a human in the long run? 90+% of the atoms are going to be replaced, there is no static form to supervene on. A human is better defined by process, which in turn determines form.

Questions like: "is touch real?" or "is cause real?" seem pretty silly. Of course these things occur. But it's also the case that a full explanation of them causes us to see them in a highly counter intuitive light. In the process view touch can be real, but it's also emergent. Objects that can touch only exist in virtue of existing stabilities, the energy well stabilities of atomic nuclei or the far from equilibrium thermodynamic system stabilities of most everyday objects.

But -

List of Definitions (An Exercise)Being: what perception and consciousness are aware of, what thinking is about.

Awareness: perception, thinking, and consciousness

Consciousness: awareness, perception, thinking.

Thinking: conscious awareness of perceptions and being.

Sensation: perception

Perception: sensation

Mind: place where consciousness, perception, sensation, and awareness happen.

:cool: EZPZ -

The irreducibility of phenomenal experiences does not refute physicalism.

I am not sure I totally agree. In the OP I suggest that irreducibility is a natural consequence of the fact that experiences are representational. I then don't think that it is coherent for a representation to be reducible to things that cannot be identified with what is being represented, like with the photo example: a photograph of Everest contains information about everest, it does not contain information about the medium the photo is on, how the photo got there, what physical processes enable us to see the information in the photo etc.

I think part of the problem is your analogy. It's not analogous to the claims of physicalism, and it's making claims that physicalists would not accept.

The photograph absolutely does have information about the medium that it is made of. I can subject a photo to all sorts of chemical tests. I can identify what it is made out of, what it dissolves in, etc. I can discover fingerprints and DNA on the photograph, which will help me determine its history. I can identify how it is that the image of Mount Everest appears there. If I am a physicalist, there is a causal, physical history linking the image to the mountain.

Information theory has generally not been thought to be incompatible with physicalism per say. There is nothing mysterious about how a photo plate comes to encode information about the light that was allowed to reach the plate. From the photo I can likely determine what time of day the picture was taken at, the weather as the picture was taken, etc. The film itself will tell me what type of device was used to take the picture and I can then use my computer, a physical device, to find all sorts of information on the exact physics that would allow a person with a camera to create such a picture.

how the photo got there

How the photo got to where it is has a physical causal history per physicalism. If it is in an unlikely place, say in a locked drawer, I can surmise that a human being put it there because any other way for the picture to end up in that place is exceedingly unlikely. The location of a photo absolutely does contain information about where the photo came from and how it got to where it is. For example, if the photo was created using antiquated technology, and shows sign of having aged, I will know the photo was taken many years ago. Based on the glaciation seen in the photograph, I might even be able to date it to within a single year or few years.

You seem to be setting up some sort of dichotomy between the "image" on the photograph and the physical photograph. But physicalism is an ontology that explicitly denies that any such dichotomy exists except in our minds. Film is physical. It encodes information about the pictures taken with it by virtue of physical processes. And, in comparison to how minds are generated, the physical processes involved in photography are very well understood in physical terms and arguably already reducible to them.

As you say, the idea of a physical substance is ill-defined and vague; however, the models that have emerged in the natural sciences seem to be successful and I think that is what we should follow when trying to decide the best way to describe things that actually exist.

Right, but science itself often doesn't make any sort of ontological claims at all. When physicists do make ontological claims, they increasingly seem to be embracing various forms of immaterialism, mostly ontic structural realism, rather than physicalism. Certainly, you can do away with physicalism without doing away with science, which is why the development of what physicalist philosophers have considered to be major problems have themselves gone unnoticed in the scientific community. Problems that might be fatal to physicalism, such as "how to coherently define supervenience" simply don't matter to science because physicalism is not a prerequisite for science. -

The irreducibility of phenomenal experiences does not refute physicalism.

I get what you're saying. The problem is that this implies that not everything can be explained in physical terms. So, this cuts against many common formulations of physicalism, such that "a complete physics can, in principle, explain everything."

Now maybe, as you suggest, we should not be surprised that such versions of physicalism fail. Perhaps we can suppose some sort of ontological monism, such that minds emerge from physical nature, but we need a certain type of predicate dualism to describe all of reality. But then what exactly is it that makes nature "physical?"

If physical facts can only describe one set of things in the world, then it seems like "physical" is a subordinate category, and that a higher category should subsume both the physical and the mental aspects of reality. Moreover, if physical facts can't describe everything, then it doesn't seem like we have causal closure, and if we don't have causal closure, I don't see the point of physicalism.

The question then becomes: what does physicalism explain that other ontologies cannot and how does it differentiate itself from objective idealism aside from a bald posit that nature is essentially "physical?" Objective idealism can be as naturalistic as physicalism, so that cannot be the relevant dividing line. The dividing line would seem to be the claim that there is something that is ontologically distinct, a substance or process that is "physical," and that this physical substance/process somehow supervenes on all that is mental in a way that is relevant enough to be worth positing. That is, physicalism has to have some sort of extra explanatory value to it after we allow that it cannot explain/describe all aspects mental phenomena.

But going the other way seems easier since all our knowledge of what we call "physical" is necessarily part of first-person experience.

I for one, am not even sure what physicalism is supposed to mean in terms of ontology anymore (although I think it's an extremely strong thesis re philosophy of mind, i.e. "that the body is essential to mental phenomena."). The natural sciences increasingly tend to describe things in terms of process, not substances. What is supervenience in the context of a process metaphysics? I don't know if it even makes sense. But without supervenience and causal closure, the idea that everything has a sufficient reason that can be described in the language of physics, I am not sure there is an ontology left to call "physicalism." At that point, "physicalism," just seems to be a stand in for "monism," "realism vis-a-vis the existence of an external world," and "naturalism," but none of these effectively differentiate it from idealism and the latter two don't even differentiate it from dualism alone.

So maybe the lesson is just to abandon "physicalism" and embrace "naturalism, monism, and realism?" -

How to choose what to believe?

To me, this forum is like the friends you were refering to. In the wild world, this sort of calm discussion is rare. People often overreact and get straight defensive which is utterly uncondusive to sorting things out.

Lies, calumny, rank knavery! How dare you assert such. I oppose all that you say and shall not dignify it with a response except to declare that it is evil, folly, heresy! -

Does Entropy Exist?

"It may be that our role on this planet is not to worship God - but to create him."

I have considered before that Hegelian conceptions of an evolving God that comes into being through our universes history could be taken in a very literal, sci-fi direction.

- First you get life, evolution, and the first intelligent life. This is the start of being coming to know itself as self.

- This journey of (self) discovery isn't complete until all the aspects of being are known by being, and so the story continues with the evolution of languages, science, and technology.

- This eventually gives rise to various versions of digital computing, genetic engineering, synthetic life, cybernetic implants, and artificial intelligence across a range of worlds that have produced lifeforms that develop to our level of technology.

- Down the road, this results in some species spreading out across their solar system to find more resources to keep the process of life and civilization going.

- In time, some species will begin to move between the stars.

- Because alien civilizations also face selection pressures-- survival of the fittest in an anarchic environment-- species will need to keep making strides in their ability to understand and manipulate nature. After all, technological development is a key determinant to who wins wars.

- Long down the road we have planet-sized brains thinking unimaginable thoughts, powered by a grid of Dyson Spheres. Massive synthetic lifeforms will live in the gentle tides of supermassive black holes so that the computation occurring across their galaxy-spanning empires occurs much faster relative to their frame of reference, enabling them to plumb the depths of being and nature.

- Eventually, one such entity will become ascendent, conquering the others. An entity that feasts on quasars for its energy sources as it fathoms itself will draw near to and attain the Absolute, incorporating all of reality into itself, fathoming its entire history and all possibilities therein.

Essentially, galaxy-spanning super brains are our inexorable future. Resistance is futile. Hegel grasped this like Maud'Dib and attempted to guide us down the Golden Path.

I for one am confident that, behind all the smoke and mirrors in the Phenomenology and the Logic, what Big Heg is really talking about is space battle cruisers and cool space fighters battling it out for galactic supremacy. -

What is Logic?I was dipping back into the Routledge handbook of metaphysics and it made me think of something. For folks who don't like thinking of logic in terms of naturalism, or logic as "out there," "in the world, sans mind," do you embrace realism towards propositions, states of affairs, facts, and events?

It seems like a fairly popular position in contemporary metaphysics to allow that these sorts of abstract entities, particularly propositions, do indeed exist. That is, there is a real set of all possible propositions that can be true or false, and likewise a real set of all possible states of affairs that can obtain or not obtain. Only some of these states of affairs are actualized; only some propositions are made true by the actual facts in the world. However, they all exist as abstract entities.

I am curious about this because objections against such abstract entities that I am familiar with tend to be made on naturalist grounds. Something like: how can a human being, a natural system, "grasp" an abstract entity like a proposition or state of affairs that exists outside space-time? How can language, which develops in space-time, come to accurately reflect these abstract entities?

But it seems to me that if these abstract entities are accepted, a second path opens up to seeing logic "out there," in the world, outside of minds or formal systems. Realist metaphysicians tend to assert that there are relationships between propositions and states of affairs, such that they map to one another. There is a relation between "I throw the rock at the window," being true and "the window breaks," being true, for example.

My point would be that, just as metaphysicians accept that there are isomorphisms between the set of all propositions, all facts, and all states of affairs, there seems to be other isomorphisms between how members of these sets relate to one another. And this set of relations would seem to be what people are talking about when they refer to "the logic of the world," or things like "the logic of natural selection, the logic of thermodynamics, etc.," i.e. a sort of "logos," external to mind and systems, but inherit to the way the world evolves.

These relations could be put in the form of broad propositions about how broad sets of these abstract entities relate to one another, i.e., propositions about "rules" that obtain for describing how one state of the universe will evolve into future states.

So, on the one hand I see a bridge between all three "types" of logic laid out in the initial definitions that comes from naturalism. Humans are natural systems and our minds formed by nature and our systems are formed by our minds. Thus there seems to be a way in which our minds and representational systems should map to things present in the world and be shaped by any patterns therein.

But on the other hand, if we are less inclined to naturalism and embrace abstract entities, then an abstract sort of logos seems to go hand in hand with the existence of entities like propositions, states of affairs, etc.

I suppose a thoroughgoing nominalism that takes logic to be solely a property of mind doesn't have this problem. But to my mind such ontological commitments seem to threaten a fall into radical skepticism and solipsism. On the other hand, from the standpoint of the "formalist," it seems possible to embrace a sort of epistemic nihilism and deflationary theory of truth that avoids having to assume that logic is ever anything more than a set of "games" we play, but this seems to have follow on consequences for epistemology as a whole and also lend itself to a sort of extreme skepticism. -

Kurt Gödel, Fallacy Of False Dichotomy & Trivalent Logic

Stop right there. It's about limitations in mathematics.

To talk about "certain classes of consistent system" can mislead someone to thinking Gödel is talking about something obscure. Yet it is the limited obscure fields in Mathematics which don't encompass arithmetic, which are the fields that need long descriptions to formalize them. And just what you can do with them (as they are likely to be extremely simplistic) more than give a theoretical description about them is usually even more difficult

I don't think anything I said gives the impression that the above is not the case. I was just thinking in terms of the ways that philosophers have attempted to generalize Godel (and Tarski's) findings beyond the scope of mathematics. Plus, more importantly, given the context of this thread's topic, that this doesn't hold the same way for paraconsistent systems (granted such systems won't be able to handle arithmetic and be consistent.)

See: my last post, TonesInDeepFreeze's post, etc. -

What is Logic?

Yes, this is the view I was getting at with approach #1, which is the most common in the study of logic itself. But I think there are obvious isomorphisms between all three definitions that are worth exploring. More on this later when I have a bit more time! -

What is Logic?

The social role of logic does bring up an interesting issue re the concept of group minds. If we take as a given that organizations can exhibit their own emergent form of intelligence, problem solving techniques, and goal directed behavior, such that organizations' goals are not merely the sum of the goals of their individual members' goals (and even cut against the goals of the individuals who compose the organizations), then doesn't the social rules of one level of organization become the "rules of thought," for the higher level entity?

No doubt many will find the idea of organizations behaving like group minds to be metaphysicaly dubious. We would need a whole thread to get into that issue in particular. I will just note that it is an idea with significant support in the realm of theories of embodied cognition and some areas of the life sciences. Ant and bee "hive minds" would be a potent example, and there is decent evidence to support the contention that the human mind itself is emergent from a number of surprisingly distinct systems. There also doesn't appear to be clear cut "levels" to group mind organization, so this would be more a sort of fractal process through which different levels of community give rise to different levels of mind. -

SortitionIn most cases I think it would be preferable to randomly select a small pool of people who then serve as a committee who hire (and fire) professional managers. Everything I've seen suggests that having professional city/county managers leads to better governance. You need democratic accountability, but it doesn't need to come by having the winner of a popularity contest manage.

Right, in MA towns below a certain size have to do the town meeting. It works better than you might expect but not great. I was almost the town administrator for a town that had an open meeting and select board. It tends to work fairly well except when you get:

1. Busy bodies who are extremely opinionated and bot open to compromise who are able to hijack the process. These folks often tend to be fairly idealistic.

2. Complex decisions have to be made like borrowing money to repair a very expensive water treatment plant or build a new school. Here, the difficulties of issuing debt, long term planning, etc. often get by the Select Board, and if they only have a part time TA, there is no one to really drive the project.

The other downside is that administrative staff who maybe shouldn't have much influence can end up wielding and ton of unchecked power. If you have a Select Board that is out to lunch you can have their admin staff do quite a bit lol.

Small towns tend to burn through town administrators because they're expected to manage while not being empowered to do so. In most cases the town manager system tends to work a bit better, although it obviously can fail too.

Fall River shows that the city administrator appointed by the mayor system can also go off the rails when the two are too tight (and committing crimes together lol) -

Does Entropy Exist?Per my original post here, which I apparently can't reply to, Terrance Deacon's "Incomplete Nature," makes a pretty good argument that entropy, constraints, and what states of a system are excluded or statistically less likely, does indeed play a causal role in nature.

It's a complex and somewhat counter intuitive argument (how do absences cause things), and it hinges on his use of the absent properties of systems to resurrect a reformed version of Aristotle's "formal cause."

I haven't digested it enough to do it justice, but maybe I'll come back or create a thread when I have. Interestingly, the actual point of the book is to try to find a way to explain the origins of consciousness, and I haven't gotten to that part yet, so we'll see if he's convincing there, but at any rate it's a great book simply for how it rethinks statistical mechanics and causation, even if it's main mission doesn't pan out. -

The von Neumann–Wigner interpretation and the Fine Tuning Problem

Notice how close this is getting to the dictum of classical metaphysics - that ‘to be is to be intelligible’.

Ha, well I'm trying to figure out if this standpoint is actually justifiable while starting from no presuppositions with Big Heg. The problem is that for some reason I thought the Logic was notoriously dense but at least shorter than the Phenomenology. Then the book arrives and it's like 1,000 damn pages.

I've made it about a third of the way through Houlgate's 500 page commentary on the first 20% of the Logic and we haven't made it to the introduction yet... and I don't think I've fully grasped everything... so I might have to get back to you on that.

That said, I can see the outlines and it seems like it might work. -

Kurt Gödel, Fallacy Of False Dichotomy & Trivalent Logic

To the original question, while I'm not super familiar with paraconsistent logic, I do think this changes things. Paraconsistent logics can retrieve naive set theory. They aren't susceptible to the principle of explosion, that anything can be proved from a contradiction.

The axiom of choice also becomes trivial in this case. Disjunctive syllogism also goes out the door though.

Such systems aren't necessarily complete, but I do believe they can be complete in cases where a classical version would not be. Here is a dialetheist (allowing for "true" contradictions) arithmetic that and can prove itself, but which is inconsistent.

Consistency is less important when explosion isn't a factor (to some degree) and the undefinability of truth is also less of an issue.

https://academic.oup.com/mind/article-abstract/111/444/817/960902

The purpose of this article is to sharpen Priest's argument, avoiding reference to informal notions, consensus, or Church's thesis. We add Priest's dialetheic semantics to ordinary Peano arithmetic PA, to produce a recursively axiomatized formal system PA★ that contains its own truth predicate. Whether one is a dialetheist or not, PA★ is a legitimate, rigorously defined formal system, and one can explore its proof‐theoretic properties. The system is inconsistent (but presumably non‐trivial), and it proves its own Gödel sentence as well as its own soundness.

Although this much is perhaps welcome to the dialetheist, it has some untoward consequences. There are purely arithmetic (indeed, Π0) sentences that are both provable and refutable in PA★. So if the dialetheist maintains that PA★ is sound, then he must hold that there are true contradictions in the most elementary language of arithmetic. Moreover, the thorough dialetheist must hold that there is a number g which both is and is not the code of a derivation of the indicated Gödel sentence of PA★. For the thorough dialetheist, it follows ordinary PA and even Robinson arithmetic are themselves inconsistent theories. I argue that this is a bitter pill for the dialetheist to swallow.

Reading some out there stuff on category theoretic attempts to formalize Hegel that I didn't understand, apparently that sort of system gets at these "perks" of not having contradiction result in explosion. -

What can I know with 100% certainty?

Within the assumption that it is a duck we can know with 100%

perfectly justified complete certainty that it is an animal.

Exactly. These sorts of judgements are certain. On the downside, they are also the sorts of judgements where the conclusion is contained in the premises. So ,they sort of amount to "provided x is true, x is true."

This is the whole: Scandal of Deduction, or "Problem of Deduction."

Funny enough, if you accept the Problem of Induction and the Problem of Deduction, then we cannot be certain of anything we learn from induction, while deduction doesn't give us anything we don't already know, making knowledge production seem near impossible. And yet, we seem to manage pretty well... enough that these objections start to seem prima facie unreasonable, even if it is hard to pin down why they are wrong. -

The von Neumann–Wigner interpretation and the Fine Tuning Problem

Sure, this is certainly true from the perspective of being able to totally predict behavior or the subjective elements of experience. But we're just looking for a broad answer for "what causes consciousness." That is, "what phenomena do I need to observe to make me reasonably confident that a system has subjective experience." There isn't any one mainstream theory for this. Rather, there is a constellation of widely variant theories that focus on anything from "all complex enough computation results in experience," to "certain energy patterns = experience," to panpsychism, to brainwaves, to a quantum level explanations.

What is surprising is that, even if we could resolve individual synapses, we aren't sure this would give us an answer. That is, most theories are such that, even if we magically had that sort of resolution, they couldn't tell us "look for X and X will show you if a thing is conscious or not."

By contrast, even for most theories of quantum foundations, we know what observations would count as supporting of falsifying different theories. If we could actually do Davies 10,000 beam splitter experiment we could confirm if the universe really "computes" or if it actually requires real numbers to describe. We can imagine that, if we could "step back" and see parallel universes, we could confirm MWI. However, it's unclear what view you would need, even of a magic sort, to confirm many theories of consciousness. How can we observe panpsychism? I've heard very mixed things.

That all said, I actually agree with you and T Clark. I think it's too early to begin throwing our hands up on the consciousness question given current technical limits. It's not like we have phase space maps of the brain lol. Nothing close. I merely brought that point up because it is popular and could be a point in CCC's favor.

But anyhow, not to get sidetracked on the consciousness question, which is maybe ancillary...

As far as we know, none of the various interpretations of quantum mechanics can be verified even in principle. They are all equivalent. There is no difference except, perhaps, a metaphysical one.

This is not the case, although it is mostly the case. Some forms of objective collapse theories do make distinct predictions about quantum behavior that differs from other interpretations, meaning they can be tested. Indeed, some versions, those where gravity causes collapse, have been tested (and falsified).

For example, simple formulations of the Diósi–Penrose model appear tohave been falsified, although the model has been kept alive through modifications (which if we're skeptics I suppose we could liken to epicycles.)

Likewise, pancomputationalist theories can be tested to some degree in theory, if not yet in practice. With enough beam splitters, one can configure an experiment that would require more information than the visible universe appears to be able to store to calculate. If pancomputationalists are correct, the universe is computable and infinite real numbers are not really needed to describe it. This would be a way to test that assumption and it would have ramifications for several interpretations of QM that posit real continua (or at least force them to be reformatted in finitist or intuitionist terms.) Such experiments might also lend credence to the advancement of intuitionist instead of Platonist flavored interpretations of mathematics vis-a-vis physics (a line advanced by Gisin), which would in turn have ramifications for many quantum theories and for arguments for eternalism writ large.

Unverified is not the same thing as unverifiable. If I'm wrong and one interpretation of QM can be verified, then your argument will mean something. Modeling the behavior of matter at the smallest scales as atoms and quarks allows generation of predictions of behavior that can be tested. QM interpretations do not.

As noted above, these interpretations have already resulted in some experiments, and ideas for experiments that could lend support to them. My point is that such experiments never get thought up if the theory isn't invented first.

Take quarks. Quarks were introduced based on pure theory. The same is true of anti-particles. The experiments that made us confident that these were real entities were only dreamed up because the theory already existed and people were interested in it. Quarks were not initially verifiable or falsifiable and were indeed attacked as pseudoscience on those grounds. But people kept working and now quarks are well-established. We won't get a breakthrough without theorizing.

As I noted, if I'm wrong and the various QM interpretations can be tested, then we can have this discussion. I'm not the only one who thinks that is unlikely. I acknowledge I am far from qualified to render an opinion on this. I'm not a physicist. I'm basing my understanding on reading what other more qualified people have written.

You might be interested in Adam Becker's book "What is Real?" It's a pretty succinct explanation of the history of quantum foundations, although it stops in the 1990s when there is really an explosion in the field and gives "It From Bit," pretty short shrift. It goes into detail about why most physicists don't and don't need to care about this sort of thing. But for those who work in quantum foundations, attitudes are quite different from the general population of physicists.

Now maybe their arguments are colored by the fact that this is what they do for a living, but they seem to have good arguments about why their work matters and how it can advance physics as a whole. And indeed, a lot of big discoveries have been made from this sort of work. Tests of Bell's Theorem were called "experimental metaphysics," originally, but they ended up having a large impact. He was on the short list for a Nobel before his untimely death for his work on locality and his work on locality stemmed from his interest and work on foundations.

They are not "a number of theories" they are a number of interpretations of one theory. The reason the Copenhagen Interpretation is in any way canonical is that it's really not an interpretation at all. It just describes how quantum level phenomena behave. Shut up and calculate is not metaphysics. It's anti-metaphysics.

Sort of. It depends on how we define theories, but even if we define theories as "only the formalism," different work in quantum foundations does in fact utilize different formalisms, making them different theories by that definition.

Copenhagen isn't "shut up and calculate." Copenhagen has a metaphysical perspective, it's one that is heavily influenced by logical positivism and Carnap. "Shut up and calculate," is seen as equivalent only because:

1. Copenhagen was the first major interpretation that gained traction.

2. It was dogmatically enforced (see Becker's "What is Real?"), and physicists pressured away from perusing other interpretations.

3. Thus, until recently, it was the "standard interpretation." Shut up and calculate just means you ignore the issue, which means the de facto explanation stays in place.

Bohr's complementarity is itself a metaphysical claim. It explicitly rules out other metaphysical claims like Pilot Waves (Bohm). If you want an interpretation with no metaphysics, that's Quantum Bayesianism (QBism). There, QM is only about proper statistical inferences about future observations, nothing more. QBism doesn't rule out Pilot Waves or parallel dimensions because it is totally silent on what exists (in mainstream versions I am aware of).

But Copenhagen also comes in for more criticism than most modern interpretations because it essentially has been falsified. Copenhagen presupposes two worlds, a quantum world where quantum phenomena happen and a classical world. This made sense back in the 50s, but today we've seen macroscopic drumheads entangled, bacteria entangled, quantum effects underpinning all chemistry, huge clouds of atoms entangled, macromolecules used in double slit type experiments. Advances in our theories like decoherence show that the binary of Copenhagen doesn't make a lot of sense.

That's why you'll often hear modern forms of Copenhagen described as "Neo-Copenhagen." A number of interpretation do hew quite close to Copenhagen, but they also change it to fit experimental data since the 1950s. For example, Roveli's Relation Quantum Mechanics has been described as essentially "reformed Copenhagen." And indeed, he draws on Mach, a huge inspiration for Copenhagen, quite a bit in his book. Although, IMO, it is different enough to be its own thing.

Most physicists don't have to care about this sort of thing, and so people tend to suppose the Copenhagen is more like QBism, being only about inference, rather than being logical positivists' attempt at an interpretation of QM.

This is a straw dog or straw man or straw something argument. The social and psychological mechanisms of consciousness have been studied for decades, centuries, millennia, with some success. The neurological mechanisms of consciousness have not been because the technology has not been available. Over the past few decades, those technologies have been evolving rapidly. Again, this is an argument that has been gone through many times on the forum without resolution.

See above in my reponse to wonderer. I am actually inclined to agree with you here. I am just noting that this is a commonly expressed position and the CCC might help alleviate it, although IMO it would do so in an unhelpful way, in the same sense that MWI solves FTP in a way that isn't helpful.

I'll admit, I find the claim that FTP isn't a problem more of a head scratcher. We have the Big Bang because a whole bunch of observed characteristics seem incredibly unlikely. We could have just said "well, in an infinite amount of time very unlikely things will happen so we can leave it at that." But we didn't. We got the Big Bang theory, one among any, and it found a lot of support.

However, we still saw all sorts of things that seemed very unlikely. This led to Cosmic Inflation being posited, a period of rapid inflation prior to the Big Bang. Cosmic Inflation helped explain a lot more observations and is now the theory in cosmology. But if we had simply said "initial conditions don't need to fit any statistical pattern because they are a sample size of one," we never would have developed the Big Band of Inflation theories.

Now, I can totally see thinking FTP is a bad argument for a creator and bad reason to embrace MWI or CCC, that makes perfect sense to me.

The question I have, then, is what is the problem with the Copenhagen interpretation?

The hard division between the quantum and classical scales is generally considered to be its main problem, but this has been revised over the years. The problem is that the revisions have sort of split into different interpretations, so it's hard to see what "Copenhagen" is today unless we return to the version that had to be revised.

But yeah, big picture there is no problem with it except for the fact that it predicts nothing different than any of the other theories, and so can't mark itself out as superior in that regard. It also doesn't answer the FTP issue in the way MWI can, although I am dubious about that being a point in favor of MWI. -

Ukraine CrisisResorting to downing airliners over your own country isn't a good look in any case.

More importantly than Prig's death though, Tokmak, a main Russian logistics hub and the ostensible primary intermediate goal of Ukraine's offensive seems to finally have come into at least base bleed artillery range, with what appear to be geolocated videos of the linchpin of Russia's southern logistics coming under heavy shelling.

It's unclear how well they can move supplies and men once they lose that hub, but the amount of reserves they threw into defending it would suggest they also think it's important. -

Kurt Gödel, Fallacy Of False Dichotomy & Trivalent Logic

This :up: . It's a statement about provability for statements in a certain class of consistent systems (those than can encompass arithmetic), using "effective procedures," roughly those that can be described with a set of instructions where the results should be the same each time and are completed in a finite number of steps and which don't require any creativity (i.e. introducing things outside the instructions). -

What can I know with 100% certainty?It seems useful to distinguish between certainty, the % confidence we have in a judgement, and precision, with how much detail our assessment has vis-á-vis what it is describing.

You can have a true description of something that is nonetheless misleading due to its lack of detail. E.g., "North Korea invaded South Korea because of Acheson"s equivocal response re defense of the First Island Chain."

While it is true that the Soviet archives show that the speech was taken as evidence that the US was unlikely to expend significant resources defending the ROK, which in turn led to the Soviets greenlighting the invasion, it's also fairly misleading. The war was likely to happen, maybe in a different form, regardless of the speech and it also seems like the speech was simply used to justify the position of the hawks in reports, who could have swayed the situation either way. Still, the speech has become a part of all histories of the war because it's an easy to pinpoint misstep by an administration that was otherwise one of the best at grand strategy in US history (Containment doctrine being formed under Truman and winning the Cold War mostly peacefully).

Likewise, "a car works by burning gas," is true, but it lacks the precision and detail of an in-depth explanation of how internal combustion engines and drive trains work, which in turn lack the detail of an engineers description of how a particular make and model of a vehicle works (e.g., if you have a turbo the engine works differently).

If we subscribe to the Principal of Sufficient Reason then it seems like total explanations will always trace backwards in time to prior causes such that any complete description may need us to explain everything, all causes from the begining of the universe, in order to explain anything (or at least anything we can't show through pure deduction).

To my mind, this suggests a sort of gradient of "accuracy," if not truth. E.g., Obiwan says Darth Vader betrayed and murdered Luke's father, Darth Vader says he is Luke's father. -

Literary writing process

I'm sort of the same. I have key scenes I want to write and so I do those and then fill them in. Mostly I've done short fiction but I have two larger projects that require this.

One is about humanity slowly, one by one, waking up in an infinite house. Think about vacant homes or office buildings when they are being shown for sale. There is furniture, but no clothes in the wardrobes. There is food that magically appears in cupboards and fridges, else how would my people survive, but only when they are unwatched.

So you have some continuous stairwells that go up for thousands of miles, large gymnasiums miles across, but mostly just a maze of small regular sized rooms. Then the story is about one guy from our world waking up there at some earlier point and also the people who are descended from human beings who showed up there centuries ago and how their culture and knowledge has changed over all this time.

The other is a fantasy book where the different schools of magic roughly map to philosophical positions. There are Platonic mages that manipulate pure forms, Aristotleans who can enchant things by messing with their essences, cause thorns to sprout from the ground, etc. Pythagoreans who attack using beams of pure light and geometries of energy, and the most powerful form, entropic energy, which works around the concept of information. Entropic magic is the most powerful but do too much and your brain gets damaged and you're ruined, while entropic mages have a habit of bursting into flames (which won't burn them if they keep control) while casting their magics.

This second one I have to write more out of order because it has a less defined scope and thus I need to figure out what can be fit in one book. I know I want a good duel scene. I want to introduce higher magic, based on abstraction, versus lower magic, based on drawing on the power of Jungian archetype creatures from the "Inside." Basically, the magic schools are roughly divided by intuition/emotion/Inside and abstraction/knowledge/Above, but they begin to run into each other for the most powerful sorcerers. -

What is Logic?

But your statement “Logic is a set of formal systems; it is defined by the formalism” (which is neither a logic formula nor a logic tautology) seemed to offer a definition for “Logic”. And valid definitions should not be tautological in the sense that what is to be defined should not occur in what is defining. Yet your other claims made your definition of “logic” look tautological (even claiming “Logic is all about tautologies” would sound tautological if it equates to “Logic is all about logic”).

It's like formalism in mathematics; there are rules for manipulating symbols and nothing else. The most austere definitions of logic I've seen tend to take the line that logical systems are like Chess, they are a set of rules that have been developed. Their relation to what they are used for in the world (e.g. the sciences) is pushed off to the side (which you see a lot in definitions of mathematics as well). I don't particularly like these definitions, but I don't think/hope I'm not misrepresenting them. The rub seems to be, "the system is what it is because that is how it is defined," and then we go from there in talking about the properties the systems have in virtue of their rules.

This isn't the only type of austere definition. There is also "logic as the study of logical truths," that is the identification of the most general truths that must be true under all conditions. This seems even more tautological, but you can make it at least more descriptive by saying it's about the truths that follow from an empty set of premises.

I’m not persuaded by the deflationary theories of truth so I can’t share your assumption.

Me either. I'm just trying to explain the bucket of answers to "what is logic," that I was trying to group together with point 1.

So “abstract systems“ refers to the possibile result of such cognitive task. I guess that’s the understanding suggested by your claim, right?

Yeah, in general. Again, I was just trying to explain what seems to be a popular collection of definitions of logic, so it's hard to generalize. In general, from my limited poking around, this does seem to be the type of "abstract" that people have in mind. That said, I have come across the argument that the "landscape of mathematical systems," are the real Platonic objects that mathematicians study, and so I imagine someone has probably made the same argument about logical systems at some point.

Indeed, I’m not even sure that such views would even justify anybody saying “a system can produce descriptions”, since the notion of “description” to me conceptually implies the idea that representations of states of affairs are distinct from the states of affairs in the world as the former refers to the latter (not the other way around), and the idea that the former can correctly or incorrectly apply to the latter (hence the distinction between “true” and “false”).

Good point.

If you mean that this thread is specifically about naturalist views of logic, then I didn’t get it but I will take it into account from now on.

No, by no means. Your replies have been interesting. I just find it interesting that naturalism is so dominant in culturally and in philosophy writ large, but that the subfield of logic seems fairly well insulated from this.

Concerning the "Scandal of Deduction", even though I do not share your naturalist assumptions, my way out is somehow similar to yours. We do not have the full list of valid representations of the world in our mind simultanously. We process them progressively according to some logic/semantic rules. And we may also fail in doing it.

Gotcha. But then why do we only progress through these rules so quickly and why are some people much faster than others at doing so? Or why are digital computers so much quicker than any person? I'm curious how that can be answered without reference to the physical differences between people or people and machines.

Sure we may be unable to describe many of our experiences to any arbitrary degree of detail. For example there are many varieties of “red” and yet we can refer to all of them simply as “red”. That’s not the point, the point is that in order to talk meaningfully about experiences we can’t put into words, we still need to apply correctly a sufficiently rich set of notions and make inferences accordingly: e.g. that the varieties of red are not varieties of grey, they are colors and not sounds, that they are phenomenal experiences and not subatomic particles, that one normally needs functioning eyes and not functioning ears to experience them, etc.

That makes sense to me. I thought you were drawing some distinction between "the world as it actually is, which might lack anything corresponding to the order we see in phenomena" and our view of things. I think I may have misread that.

The term “influence” may express an ontological notion of causality, but I find this notion problematic for certain reasons. On the other side, if we talk in terms of nomological regularities, surely I do believe that certain external facts (e.g. the light reaching our retina) correlate with visual experiences which then we have learned to classify in certain ways. That would be enough for me to talk about “influence” but at the place of ontological causal links, there are just nomological correlations plus a rule-based cognitive performance.

Yeah, I think that works for what I'm thinking of. I don't really like eliminative views on causation, e.g. Russell's "a complete description of the solar system includes no room for cause," but even accepting his view it seems like there are still relations of a sort between the world and beliefs. But this to me suggests that our perceived order corresponds to an order that exists outside of our perceiving it.

But is it logic by which physical states seem to orderly evolve into only other certain configurations of future physical states? I feel like a different word should be used because "logic" is more associated with definitions 1 and 2 I laid out. It is certainly very common in the natural sciences to read phrases like "because of the logic of thermodynamics...." etc., but it's obviously not a reference to thought in those cases.

Since they are mostly primitive concepts they can not be questioned or explained away without ending up into some nonsense or implicitly reintroducing them.

I'm reading Terrance Deacon's "Incomplete Nature," right now and it makes the same sort of argument. I'm really enjoying it, and I think he has a point here.

But Deacon is also coming from a naturalist frame, so he has different ideas about where to go from there. He has what I thought at first glance was a good argument against nominalism and the idea that all our categories are products of mind "in here," as opposed to reflections "out there." Perhaps not directly relevant to what we're talking about, since he is focused on how universals can have causal efficacy, but somewhat related:

Even if we grant that general tendencies of mind must already exist in order to posit the existence of general tendencies outside the mind, we still haven’t made any progress toward escaping this conceptual cul-de-sac. This is because comparison and abstraction are not physical processes. To make physical sense of ententional phenomena, we must shift our focus from what is similar or regularly present to focus on those attributes that are not expressed and those states that are not realized. This may at first seem both unnecessary and a mere semantic trick. In fact, despite the considerable clumsiness of this way of thinking about dynamical organization, it will turn out to allow us to dispense with the problem of comparison and similarity, and will help us articulate a physical analogue to the concept of mental abstraction.

The general logic is as follows: If not all possible states are realized, variety in the ways things can differ is reduced. Difference is the opposite of similarity. So, for a finite constellation of events or objects, any reduction of difference is an increase in similarity. Similarity understood in this negative sense—as simply fewer total differences—can be defined irrespective of any form or model and without even specifying which differences are reduced . A comparison of specifically delineated differences is not necessary, only the fact of some reduction. It is in this respect merely a quantitative rather than a qualitative determination of similarity, and consequently it lacks the formal and aesthetic aspects of our everyday conception of similarity.

To illustrate, consider this list of negative attributes of two distinct objects: neither fits through the hole in a doughnut; neither floats on water; neither dissolves in water; neither moves itself spontaneously; neither lets light pass through it; neither melts ice when placed in contact with it; neither can be penetrated by a toothpick; and neither makes an impression when placed on a wet clay surface. Now, ask yourself, could a child throw both? Most likely. They don’t have to exhibit these causal incapacities for the same reasons, but because of what they don’t do, there are also things that both can likely do or can have done to them.

Does assessing each of these differences involve observation? Are these just ways of assessing similarity? In the trivial example above, notice that each negative attribute could be the result of a distinct individual physical interaction. Each consequence would thus be something that fails to occur in that physical interaction. This means that a machine could be devised in which each of these causal interactions was applied to randomly selected objects. The objects that fail all tests could then get sorted into a container. The highly probable result is that any of these objects could be thrown by a child. No observer is necessary to create this collection of objects of “throwable” type. And having the general property of throwability would only be one of an innumerable number of properties these objects would share in common. All would be determined by what didn’t happen in this selection process.

As this example demonstrates, being of a similar general type need not be a property imposed by extrinsic observation, description, or comparison to some ideal model or exemplar. It can simply be the result of what doesn’t result from individual physical interactions. And yet what doesn’t occur can be highly predictive of what can occur. An observational abstraction isn’t necessary to discern that all these objects possess this same property of throwability, because this commonality does not require that these objects have been assessed by any positive attributes. Only what didn’t occur. The collection of throwable objects is just everything that is left over. They need have nothing else in common than that they were not eliminated. Their physical differences didn’t make a difference in these interactions.

-

What is truth?

Sorry, I didn't mean anything technical by absolute. Just in the sense that we can be relatively certain of things. Like I know 100% that the Royals won the 2015 World Series because they beat the Mets, where as I am fairly certain that the Cards won in 2006, the last time the Mets made it to the NLCS before that, but maybe the AL team won.

That doubt only happens against a background of certainty, and so cannot stand as a beginning position.

Agree 100%. It doesn't make sense to doubt something that you don't think is at least likely. Radical skepticism in this way is more like "a flight from all definiteness," a sort of epistemic rioting lol. -

What is truth?

As if triangles, parallel lines and chess were not real.

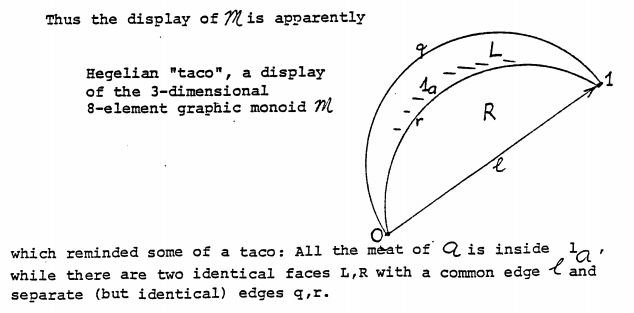

By real I just mean, "out in nature." There are no observable one-dimensional lines with no thickness that can contain an infinite number of points, are perfectly straight, and endless. Sort of like you won't find a Hegelian Taco at a food truck:

I think there is a useful distinction between the ways mathematical objects exist and the way concrete ones do.

I mean, imagine in the next several decades Berolina Chess or Ultima get so popular that 95+% of Chess tournaments and games are played in them. This becomes what Chess is, our current Chess being now a game refered to as Old Chess.

Despite this possibility, we can still be certain about what is true under the rules of Old Chess; this has to do with it being closed.