-

There Is a Base Reality But No One Will Ever Know it

I didn't mean to suggest it is majority opinion. I meant to suggest it is a not unpopular opinion in the scientific community and in philosophy, and that such claims are the type of metaphysics the Investigations seems to advocate against.

Right, but I think Wittgenstein (both versions) has a fundamentally flawed conception of language. Ordinary language is clearly flawed, whereas the later Wittgenstein makes too much of the distinction between language and other elements of experience. We understand language through experience, and have the innate ability to develop linguistic skills due to the same selection effects that shape the rest of our biology. Language isn't unique, nor is there a discrete "language system," as such in the brain. Even specialized areas like Borca and Wernicke's areas work through anatomy that is common to non-hominids.

So, IDK, I'm no Wittenstein specialist, and his style leads to multiple readings anyhow, but it seems to me like he, and those who followed him in the "linguistic turn," make the mistake of making language too distinct, too cut off from the rest of experience. This is roughly analogous to the way in which Kant cuts experience off from reality. Both views hazard against metaphysics because we either aren't in a place to use language to describe it, or we lack experience of what metaphysics takes to be the object of its study.

To my mind, these critiques have two problems:

1. It's actually impossible to avoid doing metaphysics in many areas of inquiry, so such a move is simply impractical.

2. Both moves, which are themselves critical, seem based on assertions that are not taken up critically. For Kant, the offending presupposition is that thought must necessarily be a relation between the mind and external objects, but this can't be assumed. For Wittgenstein's successors*, it is that, because meaning can be understood in terms of use, language is use. But this appears to be an artificial truncation of what language does. Language serves uses, but sometimes our meaning is obviously a reference to the external world we share (whatever the nature of this world).

My take would be, why posit the existence of things we are separated from in the first place? We are in the world and of the world. We don't need a bridge to get to the "things in themselves," or a proper language to speak of them, we need to give up the idea entirely. Likewise, for language, there can be things that are "indescribable," but this in no way entails that all phenomena are as such.

*Wittgenstein doesn't go as far with this idea as many who have followed him. He is equivocal in PI when he introduces "meaning as use (43).

But I'm largely split on the later Wittenstein. I think his warning against undue theorizing is a good one. Philosophy of language is a great example of an area where inquiry has been muddled by attempts to reduce language to "just this one thing," for the sake of theorizing. But I also see the value in theorizing in, and in systematicity, if one avoids missing the forest for the trees.

I think Wittgenstein is right that "philosophy can be therapy," but I don't agree that "good philosophy must only try to be therapy." Plus, metaphysics can be its own sort of therapy in that, at the very least, it shows the myriad ways in which thought can comprehend the world, which itself is therapeutic treatment against dogmatism. Moreover, good metaphysics gets at that sense of "wonder" at being that Aristotle describes so well. This is itself, good therapy.

If so, then there are standing waves.

Or there is just the mathematical description of them. There is this amusing passage in "Every Thing Must Go: Metaphysics Naturalized," for example:

What makes the structure physical and not mathematical? That is a question that we refuse to answer. In our view, there is nothing more to be said about this that doesn’t amount to empty words and venture beyond what the PNC allows. The ‘world-structure’ just is and exists independently of us and we represent it mathematico-physically via our theories. (158)

The book is interesting to me in that it seems to be an extreme case of trying to exorcise thought and any knower from knowledge, a project I don't think can ever be successful, not least because no one can actually think of natural phenomena in purely mathematical terms.

So you would build another, somewhat larger bottle

Sure, why not? And when that gets too small, you build another, larger bottle, or break down the walls between two other bottles. What else are we to do if we don't agree with the conclusion that calling the walls of the bottle a "pseudo problem," will somehow teleport us outside the bottle? If it seems more like refusing to fly and then claiming the problem is solved because we've stopped hitting walls? And if it's bottles all the way down, why posit anything outside of the bottles to begin with?

Wittgenstein's critique of how philosophy errs by trying to mimic the sciences does have merit. However, what is a scientific paradigm if not another metaphysical bottle? They certainly result in pseudo problems that can only be seen as such when another paradigm comes along. And yet, it seems we need paradigms to do science. And yet, we still make progress towards understanding the world, which suggests that the pseudo-problem problem may itself be another pseudo problem (the "pseudo-problem pseudo problem" if you will)

In the same way, my biggest problem with Wittgenstein's critique is that it seems to over generalize about the ways in which philosophy itself over generalizes.

This brings me to the second way that I think HW’s metaphilosophy overgeneralizes. According to HW, philosophy is purely descriptive; it should “leave the world as it is” — only describe how we think and talk, and stop at that.

I think philosophy can play a more radical role. Return to our fly. Wittgenstein was not the first to compare the philosopher to one, nor the most famous. That award goes to Socrates, who claimed that the role of the philosopher was to act as a gadfly to the state. This is a very different metaphor. Leaving the world as it is isn’t what gadflies do. They bite. As I see it, so can philosophers: they not only describe how we think, they get us to change our way of thinking — and sometimes our ways of acting. Philosophy is not just descriptive: it is normative.

I agree with Lynch. Indeed, philosophy plays a normative role in science itself, e.g. the problem of defining science itself.

As he points out, philosophers traditionally assumed that truth has a single nature — something all true statements share. Some said that all truths correspond to reality, others that all truths are useful, or are rationally coherent, and so on. Each one of these views falls short. Not every truth is useful, nor does every truth — think of the fundamental truths of morality or mathematics — clearly correspond to an objective reality. In HW’s eyes, we got ourselves into this mess by ignoring the real function of the concept, which isn’t to pick out some deep property all and only true statements share, but to allow linguistic shortcuts. And that is all there is to it: seeing that there is no “nature” to truth is the way out of the fly bottle...

First, just because we can’t reductively (“scientifically”) define something doesn’t mean we can’t say something illuminating about it. Go back to HW’s account of truth. He assumes that there is either a single nature of truth (and we can reductively define it) or that truth has no nature at all. But why think these are the only two choices?

https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/05/of-flies-and-philosophers-wittgenstein-and-philosophy/ -

There Is a Base Reality But No One Will Ever Know it

No. But I always took Wittgenstein to be saying that philosophers (and scientists doing philosophy) shouldn't be getting into "what really exists," and what doesn't, in metaphysical terms. This is something you see a lot of today though. Scientific realism seems able to say things like: "fundamental particles don't really exist, they are just mathematical descriptions of standing waves, and it's the mathematical structure that is most real," as that becomes a popular view. I took PI to be sort of warning against this sort of theorizing.

For example, the dam has really seemed to break re people exploring the implications of "parallel universes." -

There Is a Base Reality But No One Will Ever Know it

"Philosophy's job is to teach the fly the way out of the fly bottle."

Consider though that, if you could teach a fly that it is a fly, that it is in a fly bottle, and what a fly bottle is, you might be able to help the fly stop flying back into the same fly bottle over and over.

In any event, it seems to me like Wittgenstein's influence on metaphysics has really waned. Scientific realism seems more the default position than his anti-metaphysical stance. -

Does the future affect the past?

Exactly, it opens a big can of worms that some proponents seem unaware of or which they seem to think are irrelevant because such concerns are "philosophical." But, this is off base because this sort of theory is itself empirically indistinct from others and unfalsifiable, the very thing that is supposed to make theories "unscientific."

To answer the original question, this article is pretty good.https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/qm-retrocausality/

It is technical but the idea of retrocausality comes from technical considerations. -

Does the future affect the past?BTW, it's sort of ironic to see the attack on retrocausality given what she seems to like about superdeterminism.

It is worth pausing at this point to consider the metaphysical motivation for taking a retrocausal approach to quantum theory, especially in light of circumventing these no-go theorems. The orthodox reading of the no-go theorems is that, whatever is said about the ultimate conceptual and ontological framework for understanding quantum theory, it cannot be completely classical: it must be nonlocal and/or contextual and/or ascribe reality to indeterminate states. In short, quantum theory cannot be about local hidden variables. Part of the appeal of hypothesizing retrocausality in the face of these no-go theorems is to regain (either partial or complete) classicality in these senses (albeit, with—perhaps nonclassical—symmetric causal influences). That is, retrocausality holds the potential to allow a metaphysical framework for quantum mechanics that contains causally action-by-contact, noncontextual (or where any contextuality is underpinned by noncontextual epistemic constraints), counterfactually definite, determinate (although possibly indeterministic), spatiotemporally located properties for physical systems—in other words, a classical ontology.

IME, the position tends to get lumped in with "the participatory universe," but it's also actually a way back to a much more "classic world." It seems like a small price to pay if you already accept eternalism and that physics is somehow time reversible at heart TBH. -

Does the future affect the past?Do they actually have an experiment that can be interpreted as true reverse causality, that is effect in the past light cone of the cause event? The entangled pair usually space-like separated measurement events, not time-like separation. That's kind of soft retro-causality since the ordering of the events is frame dependent.

If doing something at time T2 retroactively changes X to Y at a prior time T1 (prior to T2), it's unclear to me how you could ever know the difference for sure, because you would now be in a timeline where Y was the case, not X. How could you possibly remember that X had been the case, or have a record that X was the case when it is now true that Y has been the case all along and X never was the case? This sort of retro causality is confused and you don't need any beam splitters to see why.

However, retrocausality isn't thought to work like a Hollywood time travel movie where we flip a switch and watch evidence from a past event change ala Click or Chrono Trigger. Feynman and Wheeler developed the seminal model based on, to my mind, completely valid considerations. Nor do I see how Wheeler's view is any more counterintuitive than say, an infinite number of parallel universes where all possibilities are actualized featuring infinite copies of ourselves, where we must conceptualize the empirically probabilistic nature of quantum outcomes in terms of "which universe we should bet we'll find ourselves in," Dutch Book arguments. Granted, Hossenfelder also thinks MWI is unscientific, along with internal inflation, and seems to imply the same about the Big Bang in one interview.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/qm-retrocausality/#Hist

Plus, IIRC Hossenfelder champions a one dimension, superdeterminism view of QM that is realist and local, without contextuality, meaning free choice has to go. This means a solution to apparent non-locality and violations of Bell's Inequalities is actually due to the fact that all our measurements just happen to be codetermined with their outcomes "just so," so as to give us our observed data— hidden variables at the birth of the universe. I get that this view is in some ways more intuitive, in that it makes QM "classical at heart," but I really don't get presenting it as "rescuing QM from all the wackos trying to foist weirdness onto us," since IMO it is at least as bizarre as retro causality, eternalism, and infinite universes.

IMO, there are some huge problems with this sort of superdeterminism that make degrade it into radical skepticism, but that's aside the point, it's a fine thing to speculate on. The point is that her position isn't any less metaphysical or speculative than plenty of other views so it's not a good look to present it as a sanity check saving people from grifters.

To be sure, people talking about retrocausality should be clear about what they actually mean, and up front about the fact that it is a minority opinion, but from what I've read Hossenfelder certainly doesn't present her hidden variables superdetermined interpretation like the small minority view it is either. And in any event, if you're going to write books and articles positing this sort of stuff don't go labeling opposed views "unscientific."

Which interpretation did you feel being pushed in the video? I didn't see it. I didn't see any assertion of 'what there actually is' beyond empirical measurements, but maybe I wasn't looking for them.

No, I am thinking of her other stuff. She has said before that MWI, etc. are unscientific, so it feels like the "just the facts," project has an agenda. Which is fine, it's the presentation I find off-putting.

There are paradoxes? I mean, sure if you assume naive Newtonian or absolutist sort of world, relativity might contradict that, but I find relativity reasonably free of paradoxes.

I am thinking of the Twin Paradox, the Andromeda Paradox, etc. I don't think these are paradoxes either, hence the scare quotes, but that doesn't stop them from being framed that way by people who I imagine should know better. Interpretations of relativity aren't as hot a topic as QM but there are multiple.

Yes, phase velocity of light is faster than c in cesium. So what? It's no more remarkable than the fact that I can make the red dot that my cat chases move faster than c (a lot faster). There's no FTL causality going on in any of those cases, no information getting anywhere faster than c.

Yes, but intuitively, violations of Bell's Inequalities are causal. If I do something over here and it effects a measurement outcome over there faster than light can travel, that seems like cause moving faster than light. And Einstein and others agreed. The solution of invoking information comes after the fact, it's a post hoc fix. Information is itself, famously difficult to define and is operationalized in this context with fixing this very problem in mind. We say "the entangled particle can't be a recipient of any information that results in the observed phenomena," because otherwise it would violate the theory. But nature has never cared much for our theories. Point being, I think it's a fine way to explain it, and obviously sending information as now defined in this context, FTL, would be an astounding thing. But I also see why it can be likened to Ptolemaic epicycles. It's a post hoc fix revolving around definitions that the creator of the theory was not comfortable with. -

Hidden Dualism

I too have deep problems with hand waving appeals to "information" and "complexity," re the Hard Problem. However, the Chinese Room always seemed like simply begging the question when applied to the Hard Problem.

"Imagine you don't understand Chinese," is a premise right in the thought experiment. Well, yes, given "I don't understand Chinese," then I won't understand Chinese, but as an analogy to consciousness the thought experiment fails by essentially recreating the Cartesian Homunculus. It's like asking someone to "find the neuron in the brain that speaks English."

However, I think the Chinese Room is interesting in the sense that it shows that it appears to be metaphysically possible for something to show the behaviors we associate with consciousness without being conscious. That said, if we knew what caused consciousness, the analogy might fail. It's successful because we have to rely on "correlates" of consciousness precisely because we don't have a clear causal hypothesis for what generates consciousness.

IMO, this is a problem for idealists too. Idealism is all well and good, but most idealists want to say that other people are conscious and rocks aren't, even if rocks only exist as objects of consciousness. So, they still have the problem of explaining what empirical criteria can be used to determine what is or isn't conscious. Dualists have this same problem. Is the suis generis cause of consciousness observable?

But the Chinese Room is not really relevant for that set of problems since we could take the Room apart to see how it works very easily, all you'd need is something to knock the door in. The same hasn't been true for us. -

Hidden Dualism

Interestingly, you draw a distinction between "process/behavioral," vs "mental," but it seems like all your examples could as easily distinguish between "process vs object."

But is consciousness fundamentally an object rather than a process? I might go with the latter. I cannot recall ever thinking without time passing or living the same moment more than once. It seems like first person subjective experience is a process then, not an object that springs forth from other objects or a property that objects possess. It's the difference between a song being a series of notes in time and thinking of a song as being the notes abstracted from time.

IMO, part of the gordian knot of the Hard Problem is that we have developed a 2,000 year habit of thinking in terms of "objects and substances," instead of patterns. Information theory seems like a prime example where we should be taking the process view, and yet the legacy of Platonism in mathematics seems to keep dragging it back. -

Does the future affect the past?

The problem with "no gobbledygook" attempts at explaining complex phenomena is that they very often try to get rid of one source of confusion by simplifying, and in doing so, actually add to the confusion. Take her word problem example about the age of the captain of the cargo ship. The implication here seems to be that Wheeler and everyone after him that found this experiment interesting is actually a collection of charlatans out to trick you by adding superfluous details. That isn't the case.

Neither is it the case that you can observe one outcome, then flip a switch and retroactively see it turn into a second outcome. But her point about the pattern being the same until you pair down the data is, IMO, downright disingenuous. People running the experiment don't "throw out" data randomly, or throw it out in order to get some specific result. I don't think the video even mentions the term "coincidence counter." This is like claiming that clinical trials don't show that antibiotics work because "you only end up with one group being cured and the other not being cured after you separate the data into placebo and control groups." Well, yeah, but we didn't come up with our two groups out of nowhere lol.

For a much better explanation of the same thing:

Before we rebuild a classical version of the experiment it’s very important to understand a common misconception about the detectors. In most explanations you will see claims that detections at the bottom pre-eraser detector results in a certain pattern on the top detector and detections at the post-eraser detector will result in a different pattern at the top detector. Here’s an example from a PBS video showing a pattern on an interference screen (our top detector):

This is misleading. The top detector ALWAYS shows a smooth smattering of random dots. Always. Yes, I mean always. Nobody ever runs this experiment over and over and sees an interference pattern or banded pattern emerge on the screen. It’s always a smooth, random smattering of hits. People creating these videos aren’t deliberately misleading you; it’s just a shorthand way of talking about the final results that will be produced in later steps. Once all the data has been collected, we can filter the mess of top photons and say “only show me the hits that correspond with the eraser being used” and “only show me the hits that correspond with the eraser not being used” and they will show two different patterns. An interference pattern emerges out of the data if we look at the photons who had a partner detected after going through the eraser. A different pattern emerges for the top photons whose partners were detected before the eraser.

I'm not super familiar with Sabine Hossenfelder, but from my limited exposure her "science without the gobbledygook," is actually "philosophy of physics with my particular (read: correct) interpretations." Which, if you want to do that, just say that's what you're doing and make a good case for it; you don't need to imply everyone else is "misleading" people. Like, CBU wasn't created to "get one over on the plebs."

IMO, this sort of thing grows out of the attempts to separate science from philosophy. It can't be done. When doing theory, scientists end up doing metaphysics. Physicists in particular are going to get into talking about "what there actually is," that underlies experimental results. Denying that anything exists except for empirical results is, itself, a philosophical position.

As soon as scientists acknowledge they sometimes do scientifically informed philosophy (and do so very often on this sort of topic), it becomes much easier to pinpoint where disagreements actually lie. And it turns out that the toolkit developed by philosophy is actually pretty good for, well, doing philosophy. So, once you recognize what you're doing, you can then employ that toolkit more effectively.

In any event, I think a lot of the more interesting things about the quantum "eraser" are actually better explored through Bell's work:

https://hal.science/jpa-00220688v1/document

But to bring this back to the OP: , there are a lot of other experiments that deal with how causality appears to violate our intuitions, see: tests of Bell Inequalities, modified Wigner's Friend experiments using photons, etc. These seem to call into question the idea of a referenceless, absolute "past" more than "the future effecting the past." There is actually some similarities between this and time "paradoxes" related to relativity. The trick is to come up with a coherent solution to these.

IMO, outside of retreating to radical empiricism, it seems like the more consistent ways to resolve these is to think of becoming as a local event. Otherwise, you get into this weird situation where "yeah, cause' as commonly understood can move faster than light in terms of entanglement, quantum tunneling, etc. but it isn't really cause because "information" can't move faster than light," and you have the same sort of thing with cesium gas moving faster than light (or rather the peak of a pulse gaining on the front FTL), etc. This gets confusing with classical conceptions of causation, but only if you're trying to keep an external reference frame. -

Atheist Cosmology

I will still do that if either of you would find that approach, the only fair way to progress our exchange. I have no doubt you will both have many interesting responses to my responses.

Seems plenty fair. I am more interested in the arguments against intentionality becoming intertwined with evolution and the ways in which evolution uses the same "terraced deep scan," model that Hofstadter identifies as a key element of consciousness, but this has more to do with my own private pet project of translating some of the insights of continental philosophy, and of Hegel, into the language of the modern empirical sciences.

This is of course aside the main point though, so maybe I will create a different thread on that sort of thing (e.g., the interplay between individual, group, and gene level selection, which I think are all irreducibly important and represent fractal recurrence, making an argument for seeing evolution through the lens of fractional dimensionality.)

1. Do you think the universe is deterministic? and if you do, I would appreciate a little detail as to why.

I wish I could give a good yes or no answer, but it depends on how "deterministic," is meant. Do I think the universe exhibits law-like behavior such that what comes before dictates what comes after? Yes.

Do I think the universe is computable per current definitions of computability? I am split on this. Space-time appears to exhibit the properties of being a true continuum, which means it takes infinite real numbers to describe. If this is the case, then physics is not computable, but the jury is out on this. We may find out space-time is discrete, or that something like intuitionalism holds, vindicating Wheeler's"participatory universe." I also believe we may discover a new type of "computation-like" abstraction that works with real numbers, with infinites.

Do I think it is possible to completely predict what comes after based on what comes before, ala Laplace's demon? Probably not. First because strong emergence seems to exist. If the world IS computational in the current sense, then it appears that it lacks the information capacity to generate our world without strong emergence (Davies' proof and all, which suggests strong emergence is required for the universe to be computable).

Further, physics does not appear to actually be reversible, at the microscale (CPT symmetry was violated in 2012 but the Higgs Boson overshadowed it) and certainly not in the macroscale (thermodynamics). Most importantly, wave function collapse appears to be as "empirically real," as anything in nature. This means that physics gives us vast sets of possibilities that only become actualized over time. I don't buy the arguments for eternalism and find local becoming more compelling. But even for those who embrace deterministic interpretations of quantum mechanics, it's worth noting that unitary evolution is axiomatic, and is ditched in many attempts to unify physics.

So, I think the classical scale appears to be deterministic, but the quantum scale seems to be a source of essentially infinite amounts of new information. Thus, I think our conception of determinism simply fails, that our world is deterministic in some ways but not others. What is wanted is a dialectical fusion of our concepts of determinism and indeterminism.

So I guess that is a yes or a no depending on how you look at it.

2. Is random happenstance real?

Depends on how random is defined. Quantum mechanics appears to be stochastic, probabilistic. In that sense I would say yes, which implies contingency but contingency within a boundary of possibilities.

Do you think there is 'intentionality' behind quantum fluctuations or are quantum fluctuations an example of that which is truly random?

Again, it depends on the situation. Quantum interactions out in space? I don't see a role for intentionality. Quantum measurements in a lab? Yes, what interactions occur, when and how, appear to be guided by intentionality. I am definitely a believer in experimenters' "free choice," and frankly find varieties of superdeterminism that try to fix non-locality by removing free choice to be bizarre. But quantum events don't only occur in labs, they occur everywhere, so countless quantum outcomes do have a relationship with intentionality, one that is bidirectional.

That said, you can think about things like contextuality, the fact that it seems possible that QM removed the possibility of a single "objective world," that all observers can agree too (https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.05080), and question whether such a concept is even coherent without intentionality. Plenty of people are very committed to the idea of an objective world, but I'm not sure such a thing is even coherent without subjectivity.

If the universe is not deterministic and random happenstance is real, then does it not follow that a chaotic system becoming an ordered system which gets more and more complicated, due to very large variety combining in every way possible, can begin and proceed (eventually returning to a chaotic state via entropy) without any intentionality involved?

Sure. We have the concept of a Boltzmann Brain, a human brain, generating consciousness, that can form out of random thermodynamic (or quantum) fluctuations given enough time. But randomness need not generate such things either. A universe that behaves differently than ours doesn't produce life. In fact, the constants of physics, and the vanishingly unlikely low entropy of our early universe both appear to be necessary for life to exist. We can well imagine a universe with very similar physics to ours that collapses back down into a big crunch before life has time to develop.

So, the space of possibilities has to be consistent with life as we know it. Of course, pure randomness could produce life, but if the world was completely random we shouldn't expect to see so many regularities, or even be in the same place from moment to moment.

If the universe is fully deterministic, then to me, a prime mover/god/agent with intent etc becomes far more possible and plausible. For me personally, this would dilute the significance of life towards that of some notion of gods puppets. So, my personal sense of needing to be completely free, discrete and independent of any influence or origin, involving a prime mover with intent, will always compel me to find convincing evidence to 'prove beyond reasonable doubt,' that such notions are untrue.

Right, I just don't think we can make it a neat binary. Clearly, our world is deterministic in some senses. We don't drop our kids off at school and worry they might be adults when we pick them up in six hours. We don't throw potatoes into our soup and fear they will transform into rocks when they hit the water. There are bounds on the space of possibilities, but actuality also doesn't appear to crystalize out of these possibilities until just the time that it does so.

We cannot be free if there aren't bounds on possibility. Afterall, to be free means that when you do something, you expect it to have a certain result, or range of results. Otherwise, it's like we're playing a video game where we might have 12 buttons we can press, but the buttons do something different every time, with no way to predict the outcomes. We aren't free there because our choices are at best arbitrary, based on nothing. Freedom requires constraints, for one thing to flow from another in a way that is intelligible.

But the incredible fine tuning that appears to be required for life to exist, and for it to exist in a way where it can be free? That makes me think a creator, or some sort of natural teleology, seems more plausible. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the Body

Yeah, that's essentially the point I was making. It is common to represent the non-religious view as falling into a shallow sort of dogmatism "less often," but it seems to me like the most common forms of both tend to be quite dogmatic. So, I don't know if it's a difference in kind across the two categories. Rather, the relevant distinction would lie in how the beliefs themselves have been justified/arrived at. -

Is Philosophy still Relevant?

Absolutely. To be honest, I think even the "death of [just] metaphysics," has been greatly exaggerated. Plenty of philosophy tops the best sellers list, e.g., Eckhart Tolle; it is just less likely to be written by professional philosophers these days, as the discipline has become quite specialized and philosophers often don't write in ways that will make their works widely appealing. Plenty of popular theology also has a fair amount of philosophy blended into it, commentaries on the Bible, the Patristics, etc. This shift isn't necessarily a bad thing, the role of the professional philosopher changed for a reason, although it is perhaps a sad thing, as I think that could be gained by philosophy having more widespread appeal.

I recently wrote an article on this: https://medium.com/p/1992ecb87d9

Has science taken over completely from philosophy?

To be sure, even those who would agree with Hawking would allow that philosophy remains relevant for certain necessarily subjective areas of inquiry: ethics, aesthetics, perhaps even the philosophy of language. But what about the questions:

How do we know what we know?

What actually exists?

What is fundamental?

What is subjective experience?

To my mind, these seem like inherently philosophical questions. They are questions whose answers must be informed by the natural sciences, but not the sort of questions that can be answered by the empirical sciences.

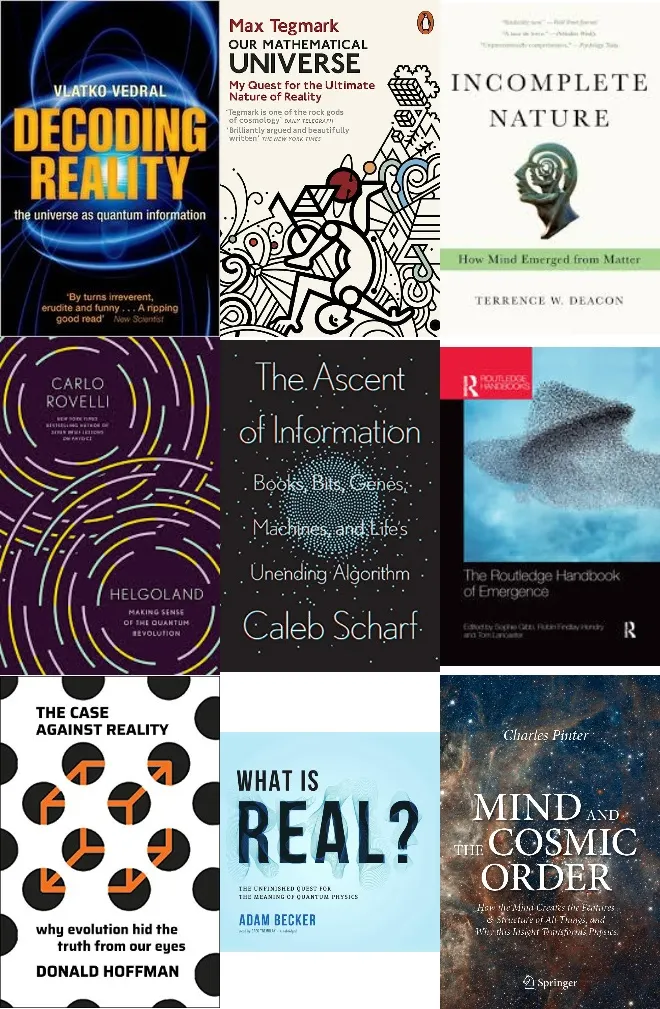

Yet it is also clear that scientists often do tend to try to answer these questions. Indeed, in the world of popular science books, I would argue that perhaps most of what is addressed are questions of philosophy— i.e., questions that are not empirically falsifiable or verifiable, questions whose answers make metaphysical claims.

The books above are either written by practicing scientists or journalists who specialize in the natural sciences. However, they are filled to the brim with hypothesis about metaphysics.

For just one example, take the popular claim in many works of popular physics: “eternalism is true.” That is, “all times, past, present, and future, exist, and exist in the same sense.” It is not clear if it is even possible to test such a hypothesis empirically. Indeed, I would argue that evidence from physics itself actually cautions against such a view. But in any event, in every case I can recall, the case for eternalism has relied heavily on philosophical arguments and analogies to mathematics (I may do an article on this issue in the future).

Metaphysics: Not So Dead After All?

Metaphysics is alive and well. Every big-name physicist appears to be advancing their own metaphysics these days.

- Carlo Rovelli has set forth a relational ontology of interaction that is similar to that advocated by second century Buddhist philosopher Lu-Trub Nāgārjuna.

- Max Tegmark has his Mathematical Universe Hypothesis, the idea that the universe is an abstract, mathematical object — a sort of ontic structural realism cum mathematical Platonism.

- John Wheeler and the many scientists he has inspired have advanced a new sort of immaterialism in the form of “It From Bit,” — the hypothesis that the universe is fundamentally composed of information.

- David Deutsch, Seth Lloyd , Vlatko Vedral, Paul Davies, etc. take this “informational” view in new directions, but all have advanced conceptions of a “computational universe.”

- Donald Hoffman, a cognitive scientist, advances his Cognitive Realism, an idealist ontology, based on an empirical argument.

- Complexity studies is often built around metaphysical claims about emergence.

- Information theory and complexity studies both tend to make claims about the ontological existence of incorporeal entities across a number of fields, e.g. that things like economic recession, turbulence, etc. actually exist and are not reducible to fundamental particles.

- The move to explain things in terms of processes instead of substances is a metaphysical move. E.g., the move from understanding fire in terms of phlogiston (a substance) to understanding fire in terms of combustion (a process); heat as the substance caloric, to heat existing in terms of random kinetic motion; life in terms of vital substance to life being understood in terms of certain kinds of far from thermodynamic equilibrium processes.

- Quantum field theory tells us the “fundamental” part(icle) can only be explained in terms of the whole, which is a mariological claim.

- Claims about computation being analogous to causality are also metaphysics.

- Black Hole Cosmology or multiverse theories (Everett’s Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics or those stemming from Eternal Cosmic Inflation) necessarily have to make metaphysical claims about what exists. Eternalism, or opposed claims of local becoming, the block universe model, the advancing block universe, the crystallizing block universe, are all, to some degree metaphysical theories. String theory works on a set of ontological claims.

That these ontological claims can be vetted using empirical evidence does not make them uniquely different from past metaphysics. As Rovelli points out, Aristotle’s physics held up for so long precisely because it jives with empirical observations. That is, Galileo’s findings were not intuitive, it requires very precise experimental conditions to confirm that a feather and a cannon ball will fall at the same rate in a vacuum. -

Ye Olde Meaning

I'm talking about how language is altered, adapted, specialized and perverted over time.

Something that is very often described in information theoretic terms using a theory that was started by an electrical engineer and furthered mostly by computer scientists and mathematicians. Or it is often explained in terms of natural selection, a theory created by a biologist, but now widely applied across a host of subjects, including language evolution, both on the grand scale and in terms of changes in slang.

When I take my car to a garage, I never ask the mechanic any questions about chemistry or history. At $60/hour, I couldn't afford to, even I were confident that he knows those things. All i need him to know is how this particular engine operates, why it doesn't, and how to rectify the issue.

I'm not saying you need to unpack all the details of friction to be able to fix brakes, but having a rough idea of it helps. I wouldn't trust a mechanic who can't tell me why bald tires are no good.

Likewise, to understand language getting a PhD in biology is probably not your best bet, but reading some biology? Yeah, that might help. This is why linguists work with cognitive scientists, biologists, doctors, neuroscientists and why all scientists work with pure mathematicians, philosophers, and logicians from time to time (more often during paradigm shifts).

Another way to think of this via the distinction between proximate and ultimate questions in the philosophy of biology.

Proximate questions ask "how?"How do words convey meaning? How do children learn language so intuitively? How do salmon find their way home to spawn each year?

Ultimate questions ask "why?" Why do we use language? Why did we develop the capacity for language? Why do salmon bother expending so much energy to return to their original homes to mate?

Biologists focus on both because the answer for one often helps unpack the answers for others. -

Ye Olde Meaning

I don't think that analogy fits. We're talking about how to understand how language works philosophically, something like: "how does language convey meaning." The car analogy would be apt if the problem was something like: "why can't x understand me when I say y and how do I make them understand?"

The philosophical view is more like the question: "how does my car work?" And yes, for that question, chemistry, the history of automobile development, mechanics, thermodynamics, etc. are all relevant parts of a complete explanation.

Humans have sex, eat, breathe, blind, drink, etc. Presumably we learn something about how and why we do these things from animal studies, else I don't know why scientists spend so much time getting animals high on drugs, neuroscientists work so much with mice, etc. -

Ye Olde Meaning

That might be reinventing the wheel, if language is outside the individual in some sense, even if it's not outside all individuals in the aggregate, outside at least in the sense of being explicitly a technology of cooperation. And then there's @Isaac's narratives, which serve multiple purposes as language does.

Good point. I was getting a little far afield. I think such a grounding is also important for resolving the is-ought gap in the manner of Honneth, etc. but that isn't necessarily key in understanding language in general. Although, it seem helpful for understanding value claims, it might be more helpful for making them, which I have prehaps conflated a bit.

This might be a mistake, looking for a framework. It could be we have many sorts of conversations and they have different sources and structures. I care about my kids and I care about democracy -- is that the same thing just because "care" is in both descriptions? Do we talk about these the same way?

I agree. See:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/826773

IMO, the challenge is too find more general principles underscoring processes without trying to reduce different processes into one thing just to get a theory that is comprehensive. It's the difference between trying to squeeze things into a box and trying to find a box that easily holds everything you need. It's easier said than done, because finding a new box and squeezing things that don't fit into an old one are easy to mistake for one another when it comes to theorizing.

As for the referenced post:

Nowhere in the above definition is the world, as we outsiders understand it, referred to by the agent's beliefs, for the agent's beliefs are understood purely in terms of the agent's mental functioning and stimulus responses. It should also be understood that from the point of view of the agent, his observation history is his "external world".

This is fine as a definition. But the "external world," as an external world still shows up in such a description. The external world is posited as part of agent's observational history, and posited as something which the agent believes to be distinct from the observational history that contains said description— an external referent. That is, we can say "there is nothing outside the text," but the text might very well say otherwise.

This assumes the agent is self conscious of course, i.e., that they are aware, through recursive self analysis, that their observational history is different from the world. But obviously agents can have the belief that the world of appearances, their observational history, is not the "real world" (Plato), and they can even believe that such a real world exists but that they can never access it (some interpretations of Kant).

An agent that differentiates between "the tree is in front of me," and "this is my view of the tree; others to my left and right have different views, and none is privilege vis-á-vis the "truth" of the tree," has moved past this description even if:

if an onlooker were to possess perfect knowledge of the agent's mentation, then as far as that onlooker is concerned, the state of the external world would be irrelevant with regards to understanding what the agent believes.

is still the case. However, I would reject the above statement unless we are talking purely abstract models. Understanding how a phenomena occurs, in this case belief formation, requires understanding what causes it. If we only understand the observational history, we can't understand how the beliefs are actually formed for the same reason that an eye can't see itself and we can't do psychology and neuroscience just by reviewing our thoughts. E.g., neuroscientists don't just scan brains, they expose people to controlled stimuli as they scan the brain; you'd get nowhere with just one half of the equation. Plus, if we accept extended minds, etc. it's unclear where to draw the line for locating an agents' beliefs in the real world.

No finite agent can perfectly encode how it comes to all its beliefs; the observational history must have gaps. If I have a meta eye that captures every detail of how my eye works then I need a meta meta eye to capture all the details of how the meta eye works, and so on. If an external observer has perfect information about an agent's observations, they still won't know everything they could know about how the agent's beliefs have developed without reference to the external world.

Self-conscious life is not naturally at one with itself. As self-conscious life actualizes its originally animal powers, it establishes a distinction between itself and its animal powers. Whatever self-conscious life is at any given point—a perceiver, a theorist, an individual outfi tted with this or that set of dispositions—it is capable of attaching the “I think” to that status and submitting it to assessment...

The abstract meaning of “consciousness”—as a distinction between awareness of an object and independently existing objects themselves— involved the agent’s awareness of himself as not merely occupying a position in the world but as occupying a position in that world.

Pinkhard - Hegel's Naturalism -

Ye Olde Meaning

Okay, then. How does that rational irrationality relate to the meaning of words?

At the most basic level, if computational theory of mind is correct, then the logic of information dictates how language can convey meaning. That doesn't mean language is reducible to quantitative theories of information, but it means that they can give us a very basic starting point for understanding communications. When dealing with emergent phenomena, it helps to know what they emerge from.

In any event, I was thinking about value statements in particular with my original post. These seem particularly tricky because of the is-ought gap. That's why the logic behind seemingly inherently subjective concepts is important, it allows us to ground them in facts. Of course "x feels y," can be an objective fact IMO, but it's a fairly inaccessible one in many ways, the sort of fact it is hard to verify or quantify the way we would like. -

Ye Olde Meaning

Of course it does. But nature and logic are not central to most human belief-systems; some belief-systems are, in fact, hostile to nature and all that is natural to a human animal. In fact, some go so far as to deny evolution and any ignore all the obvious similarities between humans and other animals.

Logic and nature need not be explicitly central to systems of belief for them to underlie such systems. People might reject that they are a type of animal, or the products of natural selection, but that doesn't stop them from being so anymore than some ancient emperors' belief in their own godhood saved them from death. That is, if cause and effect are understandable in terms of logic, and the mind is the product of nature, the the development of "irrational," beliefs is, in its own way, rational.

Indeed, it makes perfect sense for living beings to have irrational beliefs because following through all the implications of the information we are exposed to is impossible with scarce computational resources. Computation is, in its own way, communication. To be fully aware of how one is thinking requires that you subject the initial computations to another round of analysis, and so on. Perfect self knowledge then requires infinite recursion. We do have some ability to analyze our own thinking, but it is necessarily finite.

What we care about is the "difference that makes a difference." Likewise, the amount of information we can take in from our enviornment is always limited because too much entropy destroys an organism. Imagine if we tried to encode all the entropy in the microstates of the air around us? We'd have to somehow embody the chaos therein. Extremely lossy compression, and a sensory systems that mines incoming data for relevance while discarding most of what comes in, both seem essential for our perceptual system. I imagine that the same logic is part of what causes so many headaches for us re communication, we have to use heuristics to glean meaning in a time effective way.

E.g., I can read Rumi, Chaucer, Aeschylus, or Paul's letters again and again and come away with new levels of meaning, great depths lie there, but this takes time and resources.

But, just as true is the fact that knowledge is power. Genomes work by correctly encoding information about the enviornment. Technology wins wars and technology requires knowing how the world works. So being has this strange property where it has spawned life forms who can understand it very poorly but who also seem inexorably drawn on to plumb its depths in a sort of recursive, fractally recurring process of being coming to know itself. Downright trippy if you ask me. And a big role of communication is simply to further this ability to explore and encode information about the enviornment.

That only becomes a sense of justice when it's reciprocal. Did the unfairly rewarded monkeys throw the grapes at the trainer because the other group got cucumber?

The ones who benefit from injustice don't always speak out against it. From antiquity through the American Civil War, how many slave owners spoke out against the unfairness of slavery and yet owned slaves? -

Ye Olde Meaning

lol. I picked up the Routledge Contemporary Introduction to the Philosophy of Language recently because my knowledge of the field has a lot of gaps and it amazed me to see not one mention of C.S. Peirce, Saussure, or Eco, and almost none of Augustine. These four seem like maybe the top four places to go to look for a theory of meaning, but the silo walls are apparently quite strong. I was less surprised, but still saddened to see very little mention from the Continental tradition either.

I see nothing wrong with engaging in a specific type of inquiry or tradition, but you need to look outside the silo for ideas too, especially if you've been stuck in place for half a century. -

Ye Olde Meaning

If figured that might be the sense of it. But it seemed like a convenient on ramp for what I hope could be an answer for:

I am interested in figuring out a framework for people with different politics, values, etc to communicate effectively with each other

If there is, at least in principle, a way to tie values back to something outside the individual, then that provides a framework for understanding how value claims gets communicated without an infinite loop of translating mental state to mental state. Our sense of values did have to emerge out of something after all.

I don't think social norms work for this because they are too malleable, we need a more general principle that stands behind social norms, hence looking to how animals view fairness. But this might be overly speculative. -

Atheist Cosmology

Enjoy!

It did also occur to me that the possibility of extra terrestrial life is relevant here. If life exists elsewhere, it might not look anything like life here. It might not use DNA, RNA, the same amino acids, etc. Maybe it's more likely to be carbon based, but it's unclear if this is necessary either.

But then can we really define life as a certain type of chemical process? This IMO, gives weight to the computational, information theoretic view of life, which then allows "life" to simultaneously become perhaps a less meaningful term but also something that might elucidate more about a wider range of phenomena. -

Umbrella Terms: Unfit For Philosophical Examination?

There is a trade off between specificity and parsimony when using broad terms.

However, I do think there are ways in which all forms of Islam, all forms of Christianity, and all forms of capitalism are alike. There is tremendous variance in what these terms represent, but there is also an overarching similarity.

I don't think it's impossible to speak about differences between Christianity and Islam meaningfully. But, in general, when we try to do this we will tend to be talking about differences in the core exemplars of each that we are aware of. This, IMO, is where the trouble stems from. We all have different exemplars we are pointing to.

Someone who lives in the US and hasn't spent much time thinking about Christianity might think of modern American Evangelical Christianity as their key exemplar despite this example being a minority of all current Christians and quite different from most past forms of Christianity. This is essentially a case of bad induction, generalizing from an inappropriately small sample to a large one.

But diversity doesn't make a term meaningless. We can well refer to "Christians" in terms of the beliefs held by the largest sects of Christianity throughout history in a straight forward fashion, because on the average there are strong similarities in some core respects, even if outliers like Gnostics, the Amish, non-Trinitarians, etc. do exist and defy the trends for the group as a whole.

So, I think we can use umbrella terms meaningfully, but they are best used in just those cases where we actually want to discuss the broad similarities that define a term. We have to be aware that, the broader the term, the more likely it is that different people have different exemplars in mind. -

Atheist Cosmology

These are good points, I will try to provide a bit more evidence.

I don't get your point here. Such choices have nothing to do with evolution or natural selection imo. As soon as individual intent becomes the controlling mechanism over such as purely instinctive reactions, natural selection gets replaced with intelligent design/intent. Natural selection does not terminate completely but its role is much reduced.

This is human intelligent design, no natural selection involved, only human artificial selection, which indeed has intent.

I guess this is a point of disagreement: deciding that human-informed selection is somehow "unnatural" seems entirely arbitrary to me. The human is part of the natural environment of the wolf or the aurochs, and mutualism is hardly unique to humans, nor does self-domestication appear to only occur in the context of mutualistic relations with humans (e.g., bonobos, elephants, etc.), and yet these processes are based on social relations between animals. Such a view also seems to ignore the fact that many domestic animals appear to have started their road to domestication on their own initiative, domesticating themselves by coming into a mutualistic relationship with hominids, hanging around their camps waiting for food scraps.

For example, we don't think a human one day decided "wow, that cat is pretty, I shall tame it." Rather, the cats flocked to human settlements to live off the pests that thrived there, and the humans let them do so because our capacity for empathy can extend to other species and because the pests were harmful parasites- mutalism. The domestication of wolves is thought to have started in a similar way, based on the initiative of both species. Was the human part of this relation unnatural design and the feline role natural selection?

And where do we draw the line on natural and unnatural selection? Megafauna began going extinct left and right with the spread of hominids. Is this natural selection? But what then of the intentionality involved? Our distant ancestors seem to show plenty of intentionality; they bury their dead, make art, and appear to imbue both these practices with religious intent. Nor is this behavior, or tool making, limited to homo sapiens. Neither does it really take off in complexity with homo sapiens; behaviorally modern humans come long after humanity.

This is interesting in the case of dangerous game because the fact that humans hunt dangerous game ritualistically seems to be endemic. Men often "become men" in hunter gatherer societies when they take part in successful kills of the local dangerous megafauna- but then the drive to extinction is in part something quite intentional. But this extinction wave begins before homo sapiens and might have a similar causal mechanism in earlier hominids.

But the examples you mention above, corporations, languages(at least those used by humans and human made machines), people groups (I am not sure what 'elements of states,' refers to), involves intelligent human design, so yes, they would involve intent but I am unfamiliar with any compelling scientific evidence that there is correlation between such examples and natural selection.

Evolution is merely a measure of, or a record of, how species have changed over time. Natural selection is also just a measure of what species survived environmental change, and why. I cannot perceive any intent in those measures.

I think the mistake is to think of natural selection as only occurring in life. It doesn't; the concept is heavily employed in physics for non-living systems, in computer science, and a host of other areas. For example, we can see natural selection at work in the evolution of self-replicating silicone crystals, a non-living system. Indeed, one theory of abiogenesis is that such crystals were actually the scaffolding for early life, protecting RNA from the environment in a commensalism or mutualist (metabolic processes helped crystal fitness) relationship.

Natural selection occurs across far from equilibrium dynamical systems, not just those that are "living" (a poorly defined term in any event).

Previously, talk of natural selection affecting the development of languages., corporations, states., etc. was seen as a sort of loose analogy. However, more recently, information theoretic approaches in the empirical sciences have supported the contention that natural selection is also an essential concept for understanding the evolution of these higher-level entities (or at the very least, said contention is alive and well in the empirical sciences). And indeed, we see natural selection at workwithin a given lifeform, e.g. lymphocytes, neurons, etc. and at work abstractly in the success of "genetic algorithms."

That is, what was once thought to be something unique to life is now recognized to be a special case of a more general principle; exactly what we hope to find in science. Hence, Dennett's appeal to natural selection as a more parsimonious solution to any evidence of "design," ala "Darwin's universal acid." To my mind though, the mistake has been to dogmatically assert that intentionality plays no role in any of this, as a rule.

If computation gives rise to intentionality, then these complex computational processes can, perhaps, exhibit a sort of intentionality.

The choices made are often bad ones or unfortunate ones or are purely based on instinctive imperatives, rather than intellect, and so many individuals don't survive. There is no intent in that system, random happenstance and a measure of fortune/luck, that individuals made the correct 'instinctive' move, in a given scenario, is a matter of probability and circumstance and not intent.

All our choices are based on instinct. All our perceptions, thoughts, emotions, are grounded in what we are; there is no "man in the abstract." If being guided by instincts and shaped by evolution makes something non-intentional than intentionality cannot exist. If I cook because I'm hungry, that doesn't mean there is no intention behind what I do. Indeed, it seems like instinct, goals, are essential for the creation of intent.

Discussions of birth control, the problems of falling birth rates in elites, etc. go back to early antiquity across a range of cultures. I don't see how this doesn't bespeak intentionality.

The underlined words are where we differ I think. Evolution is very very slow

But this is no longer common opinion in biology. The article I posted was about the war being waged over just this fact.

The London Underground has not been around that long but the mosquitos that infest it have become a new species that will not mate with the species they descended from.

We have speciation occurring in two generations in one example. Bacteria can evolve resistances to antibiotics and antiseptics in a few days under the right conditions. Biologists also no longer agree that the Central Dogma holds; it's a point of contention. Changes in an organism's lifetime can demonstrably affect their offspring's traits, the big question is how much this should inform the received view on evolution as a whole.

And in any event, natural selection doesn't only occur in biology.

As soon as a lifeform demonstrates intent as a consequence of being self-aware, conscious and intelligent, rather than a creature driven via pure instinct imperative only, then at that point, intelligent design reduces evolution to a very minor side show for such individuals

But this would seem to imply that humans aren't the result of natural selection as respects many of their recent ancestors, since hominids appear to have had intentionality. -

Dilemma

The 20-year-old because they are more likely to contribute to the survival of the entire group. Unless my mom has a very useful skills set for this sort of thing, she is going to lose out.

This is in the abstract. In concrete terms, my own mother has several times expressed that she has absolutely no desire to live in a post-apocalyptic world and would just accept her fate, so this makes it easy for me.

Plus, in concrete terms I don't need to choose. My parents live very far away, and even if they were visiting, I live in a rural area that wouldn't be a prime target for any military attack, have a large deal of grazing land around me, numerous cattle on my land, my neighbors have pigs, chickens, ducks, sheep, etc., we have a garden, the woods are rife with deer and I have a bow and a stupid number of arrows because I lose them and find them again, and I have a stockpile of .30-06 and shells I inherited. Also, a pond stocked with bluegill, coy, and catfish that is fairly self-sustaining.

I don't love where I currently live, but it is quite good as far as apocalypses go.

The correct solution would be for me to give both my tickets to two children. If they wouldn't let me do that, I would refuse to go and tell them to give the tickets to someone else. That's what I say I would do and it would be the right thing to do, but we won't ever know what I'd really do

IDK, I don't think a bunker full of five-year-olds has good survival odds in the long term. -

Ye Olde Meaning

When people use these words in the context you describe, they are often being taciturn. When person A says "I want justice," they really mean "I want justice in line with my values and my worldview." When person B says "I want justice" they also mean the same. Of course, if persons A and B have different values or worldviews, then what "justice" looks to them is different. However I would put forward that the problem is not a misunderstanding of the word, rather that the word is being used as a short form for more than just itself. Simple elaboration clarifies the misunderstanding.

Is this assuming nominalism? That there is no "justice," or "good," that people can point to that extends outside the frame of "my desires and preferences?"

That everyone might understand justice in a different way doesn't preclude that "justice" exists. People understand what is meant by "species," "economic recession," "computation," or "fundemental particle" in different ways, but that doesn't mean the words lack a referent, right?

Values are perhaps different in that it is less possible to describe them truthfully while also describing them objectively. But objectivity ≠ truth. In some ways, moving to more objective descriptions of a phenomenon appear to lead to less accurate depictions of those phenomena.

Anyhow, values being somehow more subjective doesn't seem to preclude their having some sort of referent outside of personal experience. When we refer to "a lack of justice," in the world, it seems like we are referring not simply to our own mental states or to a collective set of mental states, but states of affairs in the world in a way not of a different kind form claims like "there is no hydrogen gas in the cannister." That is, there is a set of empirically discoverable conditions we think a certain state of affairs lacks.

Consider that many animals and young children appear to have a sense of fairness.

A sense of fairness has long been considered purely human -- but animals also react with frustration when they are treated unequally by a person. For instance, a well-known video shows monkeys throwing the offered cucumber at their trainer when a conspecific receives sweet grapes as a reward for the same task.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2023/03/230302114205.htm#:~:text=FULL%20STORY-,A%20sense%20of%20fairness%20has%20long%20been%20considered%20purely%20human,reward%20for%20the%20same%20task.

We live in a world of cause and effect. We are highly attuned to recognize these patterns, and their nuances. We become frustrated when events do not correspond to our predictions. There is a desire for regularity and this transfers over to social conditions as well, although social conditions can shift greatly over time, for humans and animals.

A desire for fairness has a certain sort of logic, even from an evolutionary standpoint. To my mind, this recalls the idea Hegel develops in the Philosophy of Right and which Honneth picks up in Freedom's Right. We can objectify values to the degree that we can understand their underlying logic in nature. And they do seem to have an underlying logic, to be something necessary rather than contingent— a solution to the game of survival. The human mind comes from nature and it would be suprising if broad similarities across species and cultured did not stem from something necessary in our development as opposed to contingent. Hence, I think a form of justice, etc. can be found implicit in the development of species and further in the development of cultures and history. But this doesn't mean that an objective Platonic form of justice exists as such, but rather that the concept is developing, unfolding, itself a complex and dynamical process.

Which is all to say, I think we have good grounds for thinking justice can refer to both our individual sense of justice, social norms, OR a higher form of justice that lies implicit within the logic of being. -

Atheist Cosmology

I find all teleological assignments to lifeforms implausible.

A wolf did not get sharp teeth because it needed them. The sharp teeth evolved not because of evolutionary intent, but due to the process of natural selection, working over a very long time.

Indeed. But I do think there is a troubling tendency to try to divorce evolution from all intentionality. I had to spend a very long time explaining to someone reviewing a paper I wrote why it is that natural selection, as applied to corporations, languages, elements of states, people groups, etc. can absolutely involve intentionality. It's like, somewhere along the line, to avoid mistakes about inserting intentionality into places it doesn't belong, a dogma was created that natural selection necessarily can't involve intentionality.

Obviously, people choose who they mate with based on intentional decisions though. Many animals are also picky about who they mate with. They also only mate if they survive and they only survive based on intentional choices they make. Intentional choices change the enviornment which in turn affects future selection pressures. Intentional behavior increasingly seems able to alter the genes that parents pass to their offspring in ways that violate the common conception of heredity.

Processes like self-domestication, particularly the high levels of self-domestication that humans enacted upon themselves, don't make sense without appeals to how individuals of the species make choices.

Normal domestication is an even more obvious example. A cow is, after all, a product of selection by the enviornment, which contains humans who intentionally bread it into livestock. I don't think there is good support for the claim that domestication is something totally new in the world, something unlike all prior evolution.

Intentionality plays a role in selection, but the selection process itself is initially not intentional. It is only intentional to the degree that life develops intentionality. Once that exists though, once a lifeform is using intentional problem solving to decide how to survive and who to mate with, then evolution is necessarily bound up with intentionality. In evolutionary game theory, we generally don't think the "players," know that they are in the game. In general, the "player" is more apt to represent the species than individuals in any case. And yet, obviously, at some point in the evolution of hominids the players very much did begin to recognize some elements of the game. "Like father like son," is appears to have been recognized by humans from at least the birth of domestication.

But the above gets at another point: if they player is the species, why do we only look at individuals for intentionality. The problem here is that information theoretic, computational theories in biology have been hugely successful. They can also show us how complex systems like an ant hive work like a "group mind," allowing for complex decision making processes, the sort of thing we associate with intentionality. No one ant knows what the hive is doing, but it's also not like any one neuron knows what the brain is doing, so objections based on that point seem libel to appealing to Cartesian Homunculi to explain intentionality.

The problem then is that the same sort of complex sample space search/ terraced deep scan and informational processes that we use to understand the brain, what we think to be the seat of intentionality, also are at work in ant hives, but ALSO work for large sets of individuals undergoing selection. E.g., lymphocytes are often cited as an example of ways in which a selection based algorithims searches a sample space.

But Hebbian Fire Together Wire Together, a pillar of modern neuroscience, uses the same selection principles! Synapses and neurons survive based on interaction with the environment. Human development involved a process of massively overproducing neurons and then having them culled by selection. Yet we tend to think this sort of selection does indeed have a purpose, making an intelligent human, and does give rise to intentionality.

However, if this sort of goal oriented selection structure is acceptable to posit for the immune system, there is, prima facie, no reason to think it doesn't generalize to species. In which case, evolution absolutely can be goal driven, even when we're talking about unicellular organisms (or members of an immune system). So, we come full circle.

Where does intentionality start and end? If we appeal only to complexity and amount of information processed then species should be MORE conscious than individuals.

But this is also a field were there is fierce controversy raging.

In 2014, eight scientists took up this challenge, publishing an article in the leading journal Nature that asked “Does evolutionary theory need a rethink?” Their answer was: “Yes, urgently.” Each of the authors came from cutting-edge scientific subfields, from the study of the way organisms alter their environment in order to reduce the normal pressure of natural selection – think of beavers building dams – to new research showing that chemical modifications added to DNA during our lifetimes can be passed on to our offspring. The authors called for a new understanding of evolution that could make room for such discoveries. The name they gave this new framework was rather bland – the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (EES) – but their proposals were, to many fellow scientists, incendiary...

By building statistical models of animal populations that accounted for the laws of genetics and mutation, the modern synthesists showed that, over long periods of time, natural selection still functioned much as Darwin had predicted. It was still the boss. In the fullness of time, mutations were too rare to matter, and the rules of heredity didn’t affect the overall power of natural selection. Through a gradual process, genes with advantages were preserved over time, while others that didn’t confer advantages disappeared.

Rather than getting stuck into the messy world of individual organisms and their specific environments, proponents of the modern synthesis observed from the lofty perspective of population genetics. To them, the story of life was ultimately just the story of clusters of genes surviving or dying out over the grand sweep of evolutionary time...

The case for EES rests on a simple claim: in the past few decades, we have learned many remarkable things about the natural world – and these things should be given space in biology’s core theory. One of the most fascinating recent areas of research is known as plasticity, which has shown that some organisms have the potential to adapt more rapidly and more radically than was once thought. Descriptions of plasticity are startling, bringing to mind the kinds of wild transformations you might expect to find in comic books and science fiction movies.

Emily Standen is a scientist at the University of Ottawa, who studies Polypterus senegalus, AKA the Senegal bichir, a fish that not only has gills but also primitive lungs. Regular polypterus can breathe air at the surface, but they are “much more content” living underwater, she says. But when Standen took Polypterus that had spent their first few weeks of life in water, and subsequently raised them on land, their bodies began to change immediately. The bones in their fins elongated and became sharper, able to pull them along dry land with the help of wider joint sockets and larger muscles. Their necks softened. Their primordial lungs expanded and their other organs shifted to accommodate them. Their entire appearance transformed. “They resembled the transition species you see in the fossil record, partway between sea and land,” Standen told me. According to the traditional theory of evolution, this kind of change takes millions of years. But, says Armin Moczek, an extended synthesis proponent, the Senegal bichir “is adapting to land in a single generation”. He sounded almost proud of the fish.

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2022/jun/28/do-we-need-a-new-theory-of-evolution

Point being life seems to explore the sample space of possible "solutions" in a multi leveled way displaying fractal recurrence, and computationally. Looking only at individuals or DNA misses a huge amount of how species actually evolve.

Again, I'm not suggesting life is necessarily intentional in evolution. If anything, this shows that there may be serious problems with computational theories of the emergence of intentionality because it seems to make "species," to the extent they exist, as intentional as many fairly complex individual animals, if not more intentional. So either intentionality doesn't just result from "really complex, goal oriented computation," or it is somehow limited by having to be computation that occurs in a certain physical substrate, or, species ARE intelligent and we just don't see it because their "thoughts" take thousands of years.

Maybe the latter isn't as implausible as it sounds. We completely missed all the amazing problem solving power and intelligence plants demonstrate for a long time simply because they move to slow for the time scales we evolved to pay attention to. -

Ye Olde Meaning

I think the "language as use," insight is simultaneously genius and a negative influence on the philosophy of language. While Wittgenstein is more equivocal in the Investigations over whether language is always use, his work has been used to build an all encompassing theory, one of the very sort he argues against in the Investigations. Language may sometimes be a game, but it isn't always a game, unless we stretch the definition of "game" to become so broad as to lose all explanatory power.

It is prima facie unreasonable to say that we don't mean things by our words outside of the structure of language. Language is, after all, a method of communication. Sometimes we very obviously are referring to objects with speech, e.g., "my car needs a new timing belt."

Now, animals also communicate, monkeys make different calls for different predators, different dances by honey bees refer to the location of food in relation to the hive, etc. When a dog shows anger, aggression, it is communicating it mental states. And, all sorts of animals communicate aggression in very similar ways, making themselves look larger, bearing their fangs and claws, making displays of strength by jumping or beating things around them, etc.

To be sure, we could perhaps describe this in terms of evolutionary game theory, but we don't think evolution is games all the way down. Also, to totally define language in terms of use seems to demand that we lapse into a hard behavioralism that denies that language sometimes is communicating our internal, subjective experiences. But even non-social animals raised in isolation communicate their internal states through body posture, facial expressions, etc. So it seems that the "use" isn't necessarily based on learned rules. IMO, language is not suis generis, but rather a type of communication, and much confusion comes from us focusing on the most complex form of communication in isolation from simpler forms.