-

shmik

207I recently read the article: Recent Literature on Truman's Atomic Bomb Decision: A Search for Middle Ground by J. Samuel Walker.

shmik

207I recently read the article: Recent Literature on Truman's Atomic Bomb Decision: A Search for Middle Ground by J. Samuel Walker.

This was after a discussion with a friend where I questioned why my whole generation was educated to believe a specific historical story about the bombing when in reality there is no consensus on the issue. This was referring to the story that the US dropped the bombs because the only alternative was a land invasion which would result in a huge loss of life.

The article reads almost like a list. A bunch of historians arguing with each other about the numbers involved with a land invasion, what Truman was aware of, whether the Japanese would have surrendered quickly even without the bombs and other topics. Each historian criticizing the others for ignoring aspects of evidence and overstating other aspects. They fit into 3 broad camps, the traditional view which is stated above, the revisionist view which is sceptical of the traditional one and thinks there were alternative reasons for dropping the bombs and also the middle view which stands somewhere between them.

Anyway that's all pretty much irrelevant.

The question is what do I do with this? Here I have a whole host of historians disagreeing with each other. I'm not so much asking what the ontological status of history is as what attitude to take towards it. The easiest thing to do would be to remain sceptical of all views, but that seems like a cop out.

I'm sure people will take the opportunity to write their own opinions of the bombing, which is fine and interesting in itself. I'm more interested in a general attitude towards historical events, especially ones which involve so much contention. -

Baden

16.7kThis doesn't just apply to historical events but to current affairs too. I had a similar problem in looking for reliable information about the recent Ukraine conflict. There you had the classic dichotomy involving Western and Russian reporting where the good guy/bad guy narrative was the same on each side only with the roles reversed. One solution would be to gather as much information as possible and try to give it weight based on level of disinterestedness and professional skill. The more disinterested and the more skillful the writer of the source material, the more accurate the information should be - all other things being equal. Another quicker and probably much less reliable method would be to take information from the two extremes (e.g. "America callously bombed Japan when it had other options just to test its atomic weapons/display its military strength" vs. "America reluctantly bombed Japan because, in order to save lives overall, it had no other choice") and presume the truth lies roughly in the middle.

Baden

16.7kThis doesn't just apply to historical events but to current affairs too. I had a similar problem in looking for reliable information about the recent Ukraine conflict. There you had the classic dichotomy involving Western and Russian reporting where the good guy/bad guy narrative was the same on each side only with the roles reversed. One solution would be to gather as much information as possible and try to give it weight based on level of disinterestedness and professional skill. The more disinterested and the more skillful the writer of the source material, the more accurate the information should be - all other things being equal. Another quicker and probably much less reliable method would be to take information from the two extremes (e.g. "America callously bombed Japan when it had other options just to test its atomic weapons/display its military strength" vs. "America reluctantly bombed Japan because, in order to save lives overall, it had no other choice") and presume the truth lies roughly in the middle. -

Shevek

42I think that it ultimately depends on worldview. The meaning of particular events emerges when it is fit coherently as a part of a narrative or contextual whole. If 'worldview' is too metaphysical for you, then I think you really only need to invoke 'ideology' for this view to be maintained. Similarly, fidelity to new events that reshape worldviews summons the past up to be recontextualized in the new narrative, such that the present is seen to be in a coherent historical connection with the past. The vitality and importance of the past reasserts itself when it demands proper re-ontologization in light of the throwing off of ideological suppressions and over-emphasis.This, I believe, lends us the importance of visiting Walter Benjamin''s reflections on the topic in "On the Concept of History":

Shevek

42I think that it ultimately depends on worldview. The meaning of particular events emerges when it is fit coherently as a part of a narrative or contextual whole. If 'worldview' is too metaphysical for you, then I think you really only need to invoke 'ideology' for this view to be maintained. Similarly, fidelity to new events that reshape worldviews summons the past up to be recontextualized in the new narrative, such that the present is seen to be in a coherent historical connection with the past. The vitality and importance of the past reasserts itself when it demands proper re-ontologization in light of the throwing off of ideological suppressions and over-emphasis.This, I believe, lends us the importance of visiting Walter Benjamin''s reflections on the topic in "On the Concept of History":

Historicism justifiably culminates in universal history. Nowhere does the materialist writing of history distance itself from it more clearly than in terms of method. The former has no theoretical armature. Its method is additive: it offers a mass of facts, in order to fill up a homogenous and empty time. The materialist writing of history for its part is based on a constructive principle. Thinking involves not only the movement of thoughts but also their zero-hour [Stillstellung]. Where thinking suddenly halts in a constellation overflowing with tensions, there it yields a shock to the same, through which it crystallizes as a monad. The historical materialist approaches a historical object solely and alone where he encounters it as a monad. In this structure he cognizes the sign of a messianic zero-hour [Stillstellung] of events, or put differently, a revolutionary chance in the struggle for the suppressed past. He perceives it, in order to explode a specific epoch out of the homogenous course of history; thus exploding a specific life out of the epoch, or a specific work out of the life-work. The net gain of this procedure consists of this: that the life-work is preserved and sublated in the work, the epoch in the life-work, and the entire course of history in the epoch. The nourishing fruit of what is historically conceptualized has time as its core, its precious but flavorless seed.

-XVII

The 'historicism' that Benjamin critiques I take to be the historiographical view of emphasizing the historian's role as 'objective' investigator, moved in his methods only by the rigours of objective empirical science, isolating the historical event from the present. But the point is that this positive science presupposes certain more fundamental interpretative assumptions which cannot be disclosed or discredited by further subsequent collection of empirical 'facts', but are always already there when the empirical data is collected, prioritized, and interpreted. In short, there is no 'objective frame' from which one can approach narrativizing history, but one is always re-appropriating the past along with one's ideological baggage, and the baggage of the present. -

ssu

9.8kThe question is what do I do with this? Here I have a whole host of historians disagreeing with each other. I'm not so much asking what the ontological status of history is as what attitude to take towards it. The easiest thing to do would be to remain sceptical of all views, but that seems like a cop out.

ssu

9.8kThe question is what do I do with this? Here I have a whole host of historians disagreeing with each other. I'm not so much asking what the ontological status of history is as what attitude to take towards it. The easiest thing to do would be to remain sceptical of all views, but that seems like a cop out.

I'm sure people will take the opportunity to write their own opinions of the bombing, which is fine and interesting in itself. I'm more interested in a general attitude towards historical events, especially ones which involve so much contention. — shmik

This doesn't just apply to historical events but to current affairs too. I had a similar problem in looking for reliable information about the recent Ukraine conflict. — Baden

Historians writing history are also people that try to make it in this world. And yes, controlling the view of the past is a path to control the discourse of the present.

Let's look at the first subject: historians trying to make their careers. Now unlike doctors or lawyers who have gained a monopoly on their profession by a legal framework, anybody can actually write history... just as anybody can be a writer. So how can an upcoming historian make it? Hit the big time? Make oneself a name in the historian circles as a "new and upcoming" historian? Simple: have a "bold new insight" on something where the findings please somebody and the whole historical story "tells something also of this time". That the new history "rattles the cages" of the "stuffy old consensus" by questioning the facts that were it was assumed that historians had an agreement. Agreeing with everything that has already being written and not offering a new look isn't going to fly one's career as an important new historian.

Popular history is the one that pleases somebody's agenda and thinking of the present. It really is something that we ask: "What can we learn from this?" And from this we get to the next field: history as a tool of present political agendas. With let's say the attitude of the Turkish state towards the Armenian genocide or the Mongolian state trying to salvage some positive light on the Mongol Empire, the political aspects of history writing should be clear. Controlling the discourse or the way present political events and phenomenons are talked about is the way of modern propaganda... especially if the people can use search engines that aren't controlled. And that is of course interlinked to the past. How we see the past influences a lot on how we see the future, and even how we estimate the future. Hence historical revisionism can and is a political tool.

The solution is here to understand when some part of history is politically charged, too close to some actor pushing an agenda and inviting some historians to promote this view, and when it's really only historians debating history without much other interests. -

Monitor

227All this casts representative democracy in a poor light. We continually vote on issues we have no real hope of understanding and synthesising, to support politicians who want to control understanding and synthesising for other aims.

Monitor

227All this casts representative democracy in a poor light. We continually vote on issues we have no real hope of understanding and synthesising, to support politicians who want to control understanding and synthesising for other aims.

Perhaps a thread on the ramifications of 100% voter turnout. -

BC

14.2kWe know quite a bit about how the Manhattan Project was conceived and how it was executed. It cost about $2 billion plus 1945 dollars -- a small share of the USA's total $341 billion plus 1945 dollar expenditure for WWII. Roughly 130,000 people were employed, a majority of them technologically untrained women. It was a crash program requiring less than three years time, though civilian nuclear physics research had been underway for some time.

BC

14.2kWe know quite a bit about how the Manhattan Project was conceived and how it was executed. It cost about $2 billion plus 1945 dollars -- a small share of the USA's total $341 billion plus 1945 dollar expenditure for WWII. Roughly 130,000 people were employed, a majority of them technologically untrained women. It was a crash program requiring less than three years time, though civilian nuclear physics research had been underway for some time.

Germany was probably the initial intended target, but they were defeated in May, 1945. A plutonium was tested on July 16, 1945 and U235 and plutonium bombs were used on August 6 and 9th.

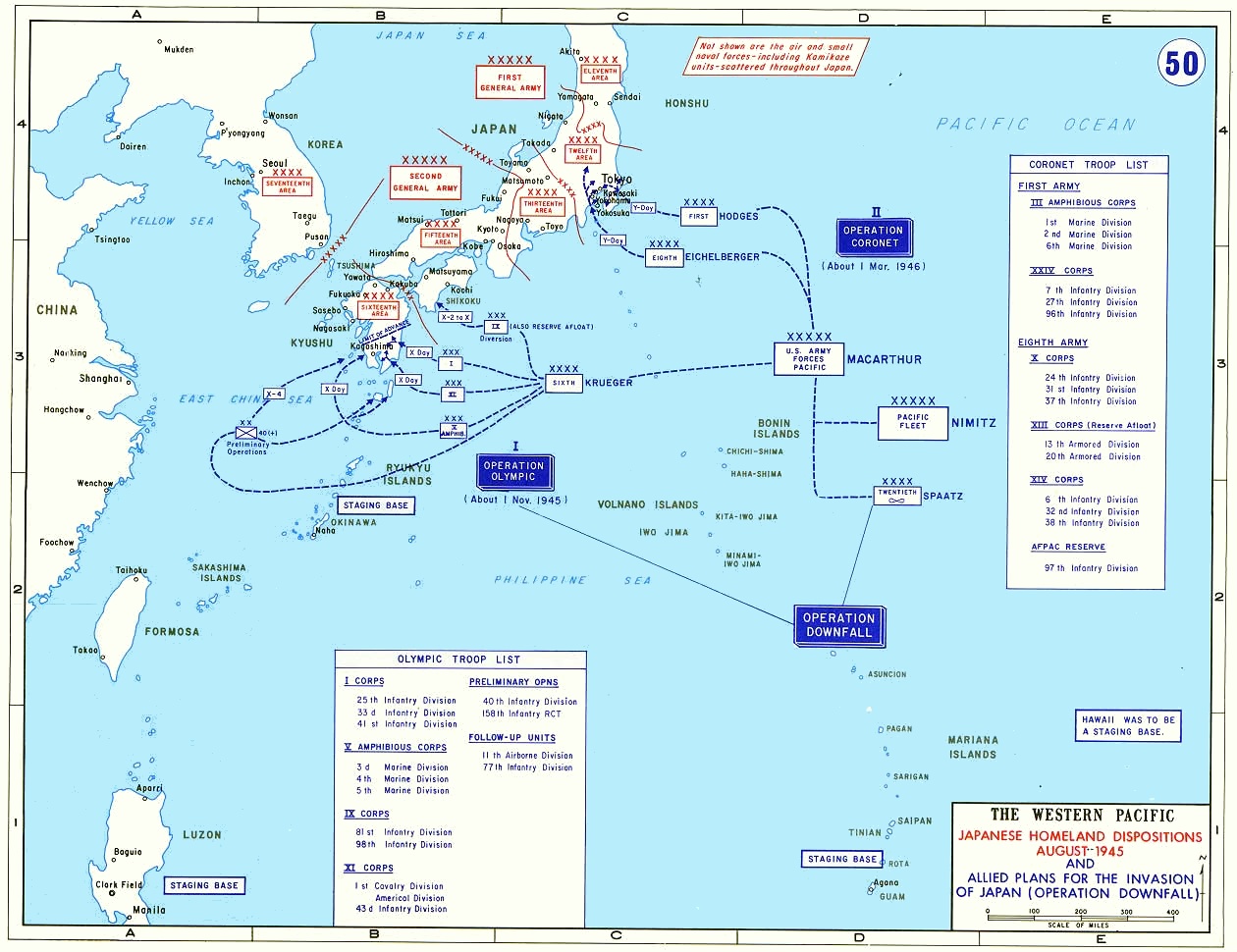

Discussions began in 1944 about how the war with Japan was to be concluded. There were at the time two or three alternatives (not including an atomic bomb which was still an unknown quantity). CIA Invasion of Okinawa and Kyushu and then a ground attack on Tokyo was one plan.

We don't need to know with complete certainty what the Joint Chiefs of Staff or the President or General Tojo and the Emperor of Japan were thinking in the summer of 1945. We know for certain that the war with Japan had been very costly, it was going to be over soon--one way or another--and it was ended.

There were tradeoffs to be made in the decision to invade, or not (from our side) and the decision to surrender, or not (from the Japanese side). No one could be sure at the time which course would be most favorable. -

shmik

207Yeh, I've had the same issues trying to work things out in the Israel-Palestine Conflict. Also it's not only history but science, for instance do mobile phones cause cancer? There was some time where it was difficult to get information about climate change and various other issues. The method you are talking about is probably what I do naturally, look at different sources, dismiss some as overly biased and imagine that the truth lies somewhere in the middle. The thing is this could be my own bias middle-ground-bias (henceforth MGB). The extreme views are more likely to use bad arguments and twist some facts, but this doesn't actually mean that they are. MGB clearly fails with climate change. Also as John Oliver pointed out, it's easy for the media to present two sides of an issue by presenting 2 scientist or 2 historians in a debate to give us the feeling that there is an even split amongst the experts.

shmik

207Yeh, I've had the same issues trying to work things out in the Israel-Palestine Conflict. Also it's not only history but science, for instance do mobile phones cause cancer? There was some time where it was difficult to get information about climate change and various other issues. The method you are talking about is probably what I do naturally, look at different sources, dismiss some as overly biased and imagine that the truth lies somewhere in the middle. The thing is this could be my own bias middle-ground-bias (henceforth MGB). The extreme views are more likely to use bad arguments and twist some facts, but this doesn't actually mean that they are. MGB clearly fails with climate change. Also as John Oliver pointed out, it's easy for the media to present two sides of an issue by presenting 2 scientist or 2 historians in a debate to give us the feeling that there is an even split amongst the experts.

Appearing less partisan is itself a persuasive technique, one that I fall for. -

shmik

207

shmik

207

Hey Shevek nice post, the problem is that it describes our actions. With certain issues my worldview is ill-formed and somewhat sceptical. I'm not necessarily concerned with an objective past, more what the hell do I do with the information. Read a bunch and assume it will culminate into a story that appeals to me?In short, there is no 'objective frame' from which one can approach narrativizing history, but one is always re-appropriating the past along with one's ideological baggage, and the baggage of the present. — Shevek -

shmik

207

shmik

207

Yes unfortunately many of the interesting issue are politically charged. And it's not like the ones that are not have never been, it's just that we have settled on a narrative for them.The solution is here to understand when some part of history is politically charged, too close to some actor pushing an agenda and inviting some historians to promote this view, and when it's really only historians debating history without much other interests. — ssu

Voter turnout in Australia is ~93% it's still the same stuff. You get one of the 2 major parties, they make the decisions.Perhaps a thread on the ramifications of 100% voter turnout. — Monitor

A lot of the historians in the article are arguing that the narrative of the trade off between land invasion and atom bomb is just political spin.There were tradeoffs to be made in the decision to invade, or not (from our side) and the decision to surrender, or not (from the Japanese side). No one could be sure at the time which course would be most favorable. — Bitter Crank -

BC

14.2kThey fit into 3 broad camps, the traditional view which is stated above, the revisionist view which is sceptical of the traditional one and thinks there were alternative reasons for dropping the bombs and also the middle view which stands somewhere between them. — shmik

BC

14.2kThey fit into 3 broad camps, the traditional view which is stated above, the revisionist view which is sceptical of the traditional one and thinks there were alternative reasons for dropping the bombs and also the middle view which stands somewhere between them. — shmik

A lot of the historians in the article are arguing that the narrative of the trade off between land invasion and atom bomb is just political spin. — shmik

Just about everything divides into three broad camps. Some people are vegans, some people eat only meat, and most people are somewhere in between. [B}Spin was from the beginning; is now, and ever more shall be, Spin without end. Amen.[/B]

We may at times be overly suspicious that politicians, generals, bankers, and everybody else are up to something other than what they appear to be doing.

History doesn't have a pre-ordained destination, but it quite often leaves pretty clear tire marks in the sand.It is possible that there was a devious plot to use the already enormous expenditures of WWII to pull off the very expensive effort to develop nuclear weapons, which the devious plotters knew would be really handy for World War III once WWII was over. Always one war ahead of the game. The weapon had to be demonstrated so that the Communist Menace would know we could fry them if they got in our way, and Japan merely offered a convenient place to do the demonstration. Nobody liked the Japs anyway, just then. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were therefore not bombed so there would be some nice fresh targets to incinerate, the better to scare the Communists with.

Truman faked any angst he would be expected to have had, had he needed to decide between atomic bombing or invasion. Roosevelt and Truman, of course, knew from the get go that Japan would fold and there would be no invasion. The invasion business was just spin. Part of The Plan. All this had been worked out by the White House, CIA, the Pentagon, and several slimy public relations firms in 1939. — Flat Out Fiction

The trajectory of events well before Pearl Harbor pointed towards a major conflict in the pacific. Japan really had embarked on an expansion of it's controlled territory, and this eventually put them in political, military, and economic conflict with the British, Americans, Russians, et al. Once the battle began, it was clear that the Allied objective would be the defeat -- not just the containment -- of the Axis powers. We succeeded, but that wasn't guaranteed.

"Knowing that the atomic bombing or an invasion of Japan was unnecessary" is writing history through a rear view mirror. Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon didn't know how the war in Vietnam was going to end. I'm sure they assumed we would win it, until it became clear that we wouldn't. Bush and Obama didn't know how their respective military offensives would turn out either. I'm sure they thought it would all go well by the end. After all, these were just two bit countries, how hard could it be?

Those who were against Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan didn't know how it would turn out either. In 1968 we may have chanted, "Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh/The NLF is going to win" but we had no more idea of what the future was going to look like than anybody else did.

The trajectory of events over the last 50 years points toward more wars by the United States (and its frequently not very enthusiastic allies) to hinder, contain, or crush local challenges to some regional status quo which threatens US hegemony. The next challenge might be in the Middle East, might be in Africa, might be in South America, might be in Asia, might be in Europe -- take your pick. Hopefully the next challenge won't come from Canada.

The trajectory of events also points toward little chance for any domestic movement to actually change US foreign policy.

One item in the global status quo that hasn't changed is the threat of nuclear weapons. The United States, Great Britain, France, Russia, China, Pakistan, India, North Korea, (and Israel, so I have heard) are so armed. All of the possessor nations also possess (or are perfecting) missiles capable of delivering atomic bombs to distant sites (not sure about Israel's missiles).

Nuclear weapons are another trajectory. Today the Union of Concerned Scientists' doomsday clock is at 3 minutes before midnight (It was 5 minutes before midnight in 2012). -

mcdoodle

1.1kI think it's possible by developing a historical imagination of one's own to have two points of view which may or may not coincide: one, what seems reasonable for the actors to have done at the time, given the pressures on them; two, how does it look in retrospect.

mcdoodle

1.1kI think it's possible by developing a historical imagination of one's own to have two points of view which may or may not coincide: one, what seems reasonable for the actors to have done at the time, given the pressures on them; two, how does it look in retrospect.

An odd sidebar of learning I've only just added to my pile is the stand that G E M Anscombe - translator of Wittgenstein and philosopher of 'Intentions' - took against Harry Truman when he was given an honorary Oxford degree, because of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Her powerful little polemic is online in various places, e.g. here: https://www.law.upenn.edu/live/files/3032-anscombe-mr-trumans-degreepdf -

ssu

9.8k

ssu

9.8k

But one has again simply not be ignorant of the history itself when somebody intreprets these tire marks.History doesn't have a pre-ordained destination, but it quite often leaves pretty clear tire marks in the sand. — Bitter Crank

You gave a perfect example above, Bitter Crank, with "All this had been worked out by the White House, CIA, the Pentagon, and several slimy public relations firms in 1939". The thing is that someone will unfortunately believe this... or similar histories. Even if the CIA was established after WW2, even if it's predecessor was established only in 1942 and Roosevelt started the whole process of creating an intelligence agency in 1941 and even if the Pentagon was started to be built in 1941. And that of course that only in the fall of 1939 Roosevelt came aware of a possibility of a very powerfull weapon from a letter co-signed by Albert Einstein. Aside from those, people will believe that somebody "knew that there wouldn't be no invasion", Operation Downfall and it's part operations "Olympic" and "Coronet".

But this kind of attitude "What-you-have-been-taught-is-all-a-lie" attitude sinks in. Vast hidden nefarious conspiracies give reason to everything: a culprit for all the misery around.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum