-

Pfhorrest

4.6kSeems like every other thread I make that even slightly insinuates that I hold these views explodes into a conversation about this and derails whatever else that thread was about... but at long last here’s the thread that’s actually supposedly to be about this.

Pfhorrest

4.6kSeems like every other thread I make that even slightly insinuates that I hold these views explodes into a conversation about this and derails whatever else that thread was about... but at long last here’s the thread that’s actually supposedly to be about this.

Who knew that "just don't hurt anybody okay? that's all that matters" was such a controversial viewpoint.

Anyway...

In a response to a comment from @Gregory on my previous thread, I wrote:

I don't think that there's any one specific purpose that is given by "God or Nature" (to borrow Spinoza) to something/someone that it/they must do to be good. Sort of the opposite of that, kind of. We start out not knowing much of anything about what the purpose of anything is, because we start out completely ignorant of what specifically is a good state of affairs, just some criteria by which to judge what's good (which is the topic of the second part of the OP that I trimmed for length), and then from there we fallibly set out to figure out what good can be done by what means, and so discover what the purpose of anything is. — Pfhorrest

That seems like a good introduction for this second part of what was going to be in that OP, which I think fits better in its own thread.

As should be expected from the positions already argued for in my previous thread about commensurablism... actually, I think maybe it's best if I just quote the most important bits that thread instead of making people click over to it:

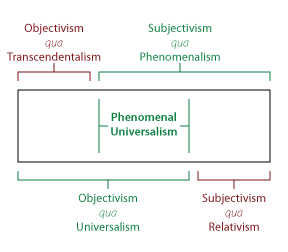

- Objectivism [...] includes both universalism :up: and transcendentalism :down:,

- Subjectivism [...] includes both phenomenalism :up: and relativism :down:,

- Fideism [...] includes both liberalism :up: and dogmatism :down:, and

- Skepticism [...] includes both criticism :up: and cynicism :down:) — Pfhorrest

If you accept dogmatism rather than criticism [the position that there is always a question as to which opinion, and whether or to what extent any opinion, is correct], then if your opinions should happen to be the wrong ones, you will never find out, because you never question them, and you will remain wrong forever. And if you accept relativism rather than universalism [the position that there is such a thing as a correct opinion, in a sense beyond mere subjective agreement], then if there is such a thing as the right opinion after all, you will never find it, because you never even attempt to answer what it might be, and you will remain wrong forever.

There might not be such a thing as a correct opinion, and if there is, we might not be able to find it. But if we're starting from such a place of complete ignorance that we're not even sure about that – where we don't know what there is to know, or how to know it, or if we can know it at all, or if there is even anything at all to be known – and we want to figure out what the correct opinions are in case such a thing should turn out to be possible, then the safest bet, pragmatically speaking, is to proceed under the assumption that there are such things, and that we can find them, and then try. Maybe ultimately in vain, but that's better than failing just because we never tried in the first place. — Pfhorrest

phenomenalism, as anti-transcendentalism, is entailed by criticism: if you are going to hold every opinion open to question, you have to consider only opinions that would make some experiential, phenomenal difference, where you could somehow tell if they were correct or incorrect — Pfhorrest

And by phenomenalism I mean to include both empiricism about reality, and hedonism about morality, both of those grounding their respective domains in their respective kinds of experiences (of things, roughly speaking, either "looking true" or "feeling good", respectively).

So, given all of the above, my general position on the nature of morality, or at least, on the objects of morality, is hedonic moralism.

That is to say, I hold that there is a universally applicable morality, as opposed to any kinds of relativism, which hold that what is moral is relative to someone's intentions or desires, or else (as I consider equivalent to those) that nothing is actually moral at all.

But I also hold that the content of that morality is entirely hedonic in nature, that if something is good or bad, it is so in virtue of the pleasures and pains, suffering and flourishing, that we experience from it compared to what we would experience otherwise, and the whole of that thing's moral value lies in those hedonic differences. It is important to note here that by hedonism, I don't mean relating to intentions or to desires, but specifically to appetites, as differentiated in my previous thread on meta-ethics and philosophy of language; just as when I speak of empiricism in my aforementioned thread about ontology, I don't mean relating to beliefs or to perceptions, but to sensations, also called observations, as also differentiated in that previous thead on philosophy of language.

In short, by hedonic moralism, I mean the view that a state of affairs is universally good, and to be aimed for by moral action, in proportion to how well it sates all the appetites of everyone, how much it brings pleasure and flourishing and relieves pain and suffering. (This focus on appetites rather than desires or intentions, and the aim to satisfy all appetites in whatever way possible even if it's not what anyone initially desired or intended, is similar to the maxims to "focus on interests, not positions" and to "invent options for mutual gain" that form a core part of the method of principled negotiation, as pioneered by Roger Fisher and William Ury).

This appeal to appetitive experience might be considered a form of what is called moral sentimentalism or moral sense theory, that being the so-called "empirical" branch of moral intuitionism (which in turn is the view that moral knowledge is not inferred from non-moral knowledge, but known directly in its own way). But whereas that position usually holds people to have an extra sense that somehow intuitively detects the morality of a situation and prompts an emotional response by which we can come to know moral facts, I hold instead that appetites are the moral analogue of senses, and that we have many different ones just as we have many different senses.

In other words, I hold that it is not the emotional responses we have to things we observe that justify opinions about morality, but rather the appetites themselves; in the same way that it is senses, not perceptions, that justify opinions about reality. And I hold that there are not properly speaking such things as moral facts, as facts are descriptive, but rather that there are universal prescriptive norms that can be justified this way, the moral analogue of universal descriptive facts justified by empirical observation through the senses.

My view is also very similar to the definition of good consequences, or utility, given by the traditional normative ethical model called utilitarianism, as promoted by philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill; but I am not here promoting the consequentialism that underlies traditional utilitarianism. I agree with utilitarians about what good ends are, but I do not hold that those ends flatly justify any and all means; as explained already in my earlier thread on dissolving normative ethics, I hold means to be of equal importance to ends, and I will elaborate further on the topic of just means in a later thread.

This hedonic moralism is a kind of value monism, as opposed to the position called value pluralism, promoted by philosophers like Isaiah Berlin, which holds that there are multiple equally valid scales of value between which we cannot translate measurements of value. In contrast, a value monism like mine holds that there is a single scale of value against which everything can be evaluated and compared. Yet I do still agree with many of the practical conclusions put forth by proponents of value pluralism; I simply deny that they entail that there are separate, incommensurable scales of value.

The archetypical example given by value pluralists is that for a given woman, a life as a mother and a life as a nun, while incompatible, may both be of value, neither able to be ranked as a better life than the other. I agree that in principle that may be true, for some particular women; but I contend that for other women one or the other life may be a universally better choice; and that even for those for whom one cannot be ranked above the other, that is because the two choices rank equally on the same scale of value.

Value monism as I support it does not entail any sort of absolutism, that says that certain kinds of choices are always better than other kinds of choices for all people in all circumstances. It only entails that for a particular person in some particular circumstance, it is possible in principle to weigh their options against each other, and determine either which one is better than the other, or that they are of equal value, on the same scale.

Establishing the criteria of that common scale of value against which to compare different possibilities is where the work of philosophy in this area ends, and the ethical sciences proposed in my previous thread on dissolving normative ethics are to take over. Just as ontology, on my account, only goes so far as establishing what it means for something to be real, or the criteria by which to judge the reality of things, but says nothing at all about what in particular is real, leaving that work up to the physical sciences, so too teleology, on my account, only goes so far as establishing what it means for something to be moral, or the criteria by which to judge the morality of things, but says nothing at all about what in particular is moral, leaving that work up to the ethical sciences.

Just as it does not suffice in practice to simply say that reality is whatever satisfies all observations, even if that is strictly true, because the physical sciences still need to do the further work of actually figuring out what abstract objects postulated by what theories do satisfy all observations, so too it does not suffice in practice to simply say that morality is whatever satisfies all appetites, even if that is strictly true, because the ethical sciences still need to do the further work of actually figuring out what proficient goods employed by what strategies do satisfy all appetites.

And just as the foundational field of the physical sciences is physics itself, so too I hold that the foundational field of such ethical sciences is the proper referent of the term "ethics" itself. But just as the physical sciences cannot proceed from ontology alone, but first need also a method of knowledge, that in turn hinging on the nature of the mind and its relation to reality, so too the ethical sciences cannot proceed from teleology alone, but first need also a method of justice, that in turn hinging on the nature of the will and its relation to morality.

I plan to do further threads on those topics (the will and its relation to morality, and the methods of justice) as soon as this one wraps up. -

Sir2u

3.6kI plan to do further threads on those topics (the will and its relation to morality, and the methods of justice) as soon as this one wraps up. — Pfhorrest

Sir2u

3.6kI plan to do further threads on those topics (the will and its relation to morality, and the methods of justice) as soon as this one wraps up. — Pfhorrest

I hope someone has enough time to read them!

I hold that there is a universally applicable morality — Pfhorrest

I cannot see that this would work, if my pleasure is to see you in pain and suffering. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI cannot see that this would work, if my pleasure is to see you in pain and suffering. — Sir2u

Pfhorrest

4.6kI cannot see that this would work, if my pleasure is to see you in pain and suffering. — Sir2u

This is the point of distinguishing between appetites and desires: an appetite is not aimed for any specific state of affairs like a desire is, it’s just a feeling that calls for something or another—and there’s always multiple options—to sate it.

And it’s also related to the problem of confirmationism and its analogue consequentialism that I’ll go into in the later thread on justice. “If you suffer, I will enjoy it” plus “I should enjoy myself” doesn’t logically entail “you should suffer”; that would be affirming the consequent.

You should enjoy yourself rather than suffer. Also, I should not suffer but rather enjoy myself. Those are necessary conditions of something being good. You enjoying yourself is not, however, a sufficient condition of something being good; if something causes you enjoyment but me suffering, or vice versa, it’s bad, and something else that brings us both enjoyment rather than suffering must be found if we are to bring about good.

If that something else is not something that either of us wanted at the outset, that’s fine; we were both wrong about what was good. It’s up to us to figure out what we should both want, that will satisfy both of our appetites. -

Sir2u

3.6k

Sir2u

3.6k

So a person that enjoys the suffering of others can never be happy. Would it not be immoral to deprive that person of their happiness unless they found someone who's happiness is suffering.

But would it not be also immoral to allow a person to debase themselves by being the object someones desires to hurt them. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo a person that enjoys the suffering of others can never be happy. — Sir2u

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo a person that enjoys the suffering of others can never be happy. — Sir2u

They can and should, we just have to find some alternate means to their happiness. There’s never only one route to happiness. Just because X makes you happy doesn’t mean X is good; but if X it to be good it must make you happy.

“P -> Q” does not equal “Q -> P”. -

Sir2u

3.6kUniversal rules have to apply to everyone, right.

Sir2u

3.6kUniversal rules have to apply to everyone, right.

I had a workmate many years ago, he was slightly mentally handicapped. Seriously the only joy in his life was his collection of model trains. Nothing else brought him any happiness at all. Not food, he ate whatever was available without even thinking about it, nor the ladies, he was not bad looking and attracted several ladies attention, not money, he worked to buy the model trains his disability pay would not buy.

Many tried and failed to get him interested in other thing but his happiness until the day he died was his trains.

It would be immoral to try to force someone to enjoy things they did not and a waste of time trying to find those things. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kIt would be immoral to try to force someone to enjoy things they did not and a waste of time trying to find those things. — Sir2u

Pfhorrest

4.6kIt would be immoral to try to force someone to enjoy things they did not and a waste of time trying to find those things. — Sir2u

It would be immoral to force them (to do something they don't enjoy, not just to stop doing something that makes others suffer), sure, but definitely not a waste of time trying to find ways to make them happy that didn't in turn make other people suffer. That might be very hard, but it's never logically impossible.

At the ridiculous extreme, a scenario where everyone was in their own virtual world experiencing exactly whatever made them feel best, even if that was the appearance of other people suffering (so long as nobody was actually experiencing that suffering in the first person), would be one universally good solution. Actually attaining that would be pretty hard, of course, and finding solutions that don't require those extremes could be really hard too. But that's the direction to aim toward if we're trying to make things more good.

Is the "we" a branch of government? Or any other coercive agent? — jgill

In this context "we" is whoever is trying to figure out what a good state of affairs would be. They might not necessarily be doing anything about it, just trying to figure out what it would be. Alice hurting Bob for her enjoyment would not be good, even if not doing it leaves Alice displeased ceter paribus; but Alice being displeased would also not be good; so if we, whoever we are, are trying to figure out what would be good, we need to figure out at least what would please Alice without hurting Bob.

Talking about coercion and government is getting a little ahead of the game here, as I'll go into those later in my other threads on the methods and institutes of justice (respectively), but spoiler for those threads: I'm generally against coercion. -

javi2541997

7.2k- Objectivism [...] includes both universalism :up: and transcendentalism :down:,

javi2541997

7.2k- Objectivism [...] includes both universalism :up: and transcendentalism :down:,

- Subjectivism [...] includes both phenomenalism :up: and relativism :down:,

- Fideism [...] includes both liberalism :up: and dogmatism :down:, and

- Skepticism [...] includes both criticism :up: and cynicism :down:) — Pfhorrest

Interesting. Thanks for sharing it. This is something new I just learned today :100:

My view is also very similar to the definition of good consequences, or utility, given by the traditional normative ethical model called utilitarianism, as promoted by philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill; but I am not here promoting the consequentialism that underlies traditional utilitarianism. I agree with utilitarians about what good ends are, but I do not hold that those ends flatly justify any and all means; as explained already in my earlier thread on dissolving normative ethics, I hold means to be of equal importance to ends, and I will elaborate further on the topic of just means in a later thread. — Pfhorrest

This reminds me about Karma. It is true that somehow we cannot include Karma as a philosophical argument or method because it is more connected to religion. Nevertheless it is interesting bringing it here in the thread because all of those who defends karma try to follow:

The principle of karma, wherein intent and actions of an individual (cause) influence the future of that individual (effect):[2] good intent and good deeds contribute to good karma and happier rebirths, while bad intent and bad deeds contribute to bad karma and bad rebirths

So I guess it is similar to utilitarianism as you explained before previously. Also I am agree with you of not holding at all this methods of thinking because not necessarily the end is justify.

Also, the las comment about this, it is interesting how “indiology” explains Karma in this different ways:

their definition is some combination of (1) causality that may be ethical or non-ethical; (2) ethicization, i.e., good or bad actions have consequences; and (3) rebirth.

It is interesting to point out how Karma put emphasis about rebirth. Probably this is another view from a metaphysical perspective.

but first need also a method of justice, that in turn hinging on the nature of the will and its relation to morality. — Pfhorrest

Agreed. We have to developed more and more the justice in terms of morality and efficiency. I guess, as you explained, there is a correct relation between all of these concepts.

I plan to do further threads on those topics (the will and its relation to morality, and the methods of justice) as soon as this one wraps up. — Pfhorrest

I am waiting for this! Justice and its methodology is one of the topics I am most interested about. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kInteresting. Thanks for sharing it. This is something new I just learned today :100: — javi2541997

Pfhorrest

4.6kInteresting. Thanks for sharing it. This is something new I just learned today :100: — javi2541997

You're welcome, but please note that those are my personal technical uses of those terms, that I do think track generally with common usage, but you probably won't find anybody else using them all in exactly that same way. I just quoted that bit from my older thread so that my use of those terms in the other quoted bits would make more sense. -

javi2541997

7.2k

javi2541997

7.2k

I just quoted that bit from my older thread so that my use of those terms in the other quoted bits would make more sense.

Ok! I will keep it in mind. Thank you for the advices :up:

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Sarvastivada Buddhist Arguments for Karma: Thoughts & Feedback? (A little long)

- Logical Arguments for God Show a Lack of Faith; An Actual Factual Categorical Syllogism

- Peter Kreeft and Ronald K. Tacelli - Twenty Arguments for the Existence of God

- How long will human beings last? Is technological innovation superior to natural innovation?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum