-

Shawn

13.5kSo, I am having a fit over logic and mathematics.

Shawn

13.5kSo, I am having a fit over logic and mathematics.

Anyway, were logical positivists in their assertion of simples and atomic facts implicitly referencing Plato? It would seem that there can be an infinite of state of affairs in logic; but, mathematics imposes constraints on logic or is it the other way around? -

Wayfarer

26.1kActually the basic book of logical positivism, was A J Ayer, Language, Truth and Logic. I did study it, but I don't recall anything about 'simples' in it. The main thrust was verificationism - that propositions ought to be, in principle, verifiable with respect to an actual state of affairs. Metaphysical propositions were therefore literally nonsensical, because they didn't refer to anythng which could ever be validated in those terms. Assertions about what ought to be the case were like expressions of emotion - rather like the 'boo-hiss' theory of ethics. Mathematical and other a priori truths were true simply because their conclusions were entailed by their premisses.

Wayfarer

26.1kActually the basic book of logical positivism, was A J Ayer, Language, Truth and Logic. I did study it, but I don't recall anything about 'simples' in it. The main thrust was verificationism - that propositions ought to be, in principle, verifiable with respect to an actual state of affairs. Metaphysical propositions were therefore literally nonsensical, because they didn't refer to anythng which could ever be validated in those terms. Assertions about what ought to be the case were like expressions of emotion - rather like the 'boo-hiss' theory of ethics. Mathematical and other a priori truths were true simply because their conclusions were entailed by their premisses.

Ayer's book was to be brought undone by the fact that it fell victim to its own criteria - because nothing in the book was really verifiable in terms of some 'state of affairs'. What 'state of affairs' could prevail, that showed that nothing other than 'states of affairs' could ever be spoken about?

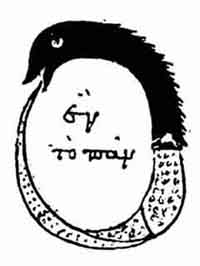

This was one of the lessons I was taught by my lecturer, David Stove, who said that positivism, in its criticism on most of what was thought to be 'philosophy' was very much like the mythical uroborous, the snake that consumes itself:

'The hardest part' he would say, 'is the last bite'. :-) -

Shawn

13.5kRudolf Carnap defends the realist view of abstract objects in his Empiricism, Semantics, and Ontology. — quine

Shawn

13.5kRudolf Carnap defends the realist view of abstract objects in his Empiricism, Semantics, and Ontology. — quine

On what grounds does he do this without evoking metaphysics? Did anyone ever get around to doing that? I know Russel and Whitehead tried really hard, yet Godel disproved them in one blow, well actually two blows.

If anyone ever follows my threads I believe the only way to prove or disprove this is via confirming that reality can be simulated to a certain degree in a sufficiently complex computing machine. The Church-Turing-Deutsch Principle provides a very elegant view on supporting this in that if something within a set contains the elements of the set then that set can be replicated in a smaller degree within that set itself. However, we don't know if there is a larger set than the set we occupy, and there really doesn't seem to be any way of knowing that for sure; but, then the fact that the same set can be replicated within the same set but to a smaller degree would seemingly point that it's possible. -

Michael

16.8kPlatonism is often understood as realist view of abstract objects in contemporary sense. Rudolf Carnap defends the realist view of abstract objects in his Empiricism, Semantics, and Ontology. — quine

Michael

16.8kPlatonism is often understood as realist view of abstract objects in contemporary sense. Rudolf Carnap defends the realist view of abstract objects in his Empiricism, Semantics, and Ontology. — quine

On what grounds does he do this without evoking metaphysics? Did anyone ever get around to doing that? I know Russel and Whitehead tried really hard, yet Godel disproved them in one blow, well actually two blows. — Question

quine's claim here is misleading. Carnap didn't accept realist ontology but realist language. As explained here:

Carnap states that the decision between realism and instrumentalism should be discussed in the form (1974, p. 256): “Shall we prefer a language of physics (and of science in general) that contains theoretical terms, or a language without such terms?” Carnap’s preference, as very clearly stated in the reply to Hempel, is to adopt the former alternative, and so his choice, as he now understands the issue, is to adopt precisely the language of realism.

Does this mean that Carnap is now committed to a realist epistemology and metaphysics (of the kind defended by Psillos, for example), which aims to “explain” the success of science by appealing to pre-existing objective natural kinds in the world, a theory of “factual reference” linking theoretical terms to such objective natural kinds, and an epistemological defense of the “no miracles” argument against the “pessimistic meta-induction”? Not at all. Carnap’s whole point is to replace the question “are theoretical entities real?” with the question which form of language we should prefer—and prefer for purely pragmatic or practical rather than theoretical reasons. -

Wosret

3.4kI doubt that Socrates was a platonist, lol.

Wosret

3.4kI doubt that Socrates was a platonist, lol.

Yeah, he said lots of stuff, but he also denied really knowing anything. The point of most of his discussions wasn't to prove anything positively right, but rather, to inspire doubt and wonder. To make you second guess what you believe, being offered an alternative of equal (or even greater) plausibility. He liked to approach people that figured that they were experts, or knew what was what, and then leave them a whole lot less certain of that.

His introduction of the conscience within himself, and his paralleling, or embodying it in the form of the gadfly, rousting the proud and strong steed (Athens) from complacency and sloppiness, rather than taking for granted its truth, and righteousness.

Socrates always seemed as a fable to me. A story about not taking things at face value, or at appearance, and the utility, and importance of a healthy level of doubt, and wonder. Never want to be too convinced of anything...

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum