-

Bylaw

559

Bylaw

559

It's not just the deities rules, it's their identities, personalities, powers, length of lifetime, how they are conceived (the differences between Loki and Vishnu are enormous), moral character, substance and more. Some of them are localized to specific spots. Most deities lack all the omni-adjectives of the Abrahamists. Some are really quite abstract and/or transcendant, others extremely concrete and/or incarnate. The range of emotions or even if they have emotions has a spectrum. Some of the can have sex with humans or animals. The ontological diversity is enormous.What the god(s) command may be quite different, say requiring sacrifice of some kind, maybe even murder in certain cults or we can metaphorically speak of Westen culture under the guise of the god of money. — Manuel

I don't mean this insultingly at all but how can you know how a cognitively smarter species would look at us?A theoretically "smarter" - in terms of having more powerful cognitive capacities than we do, would look at people at consider us as we consider other creatures, we are by and large the same, but the differences we see between us, look considerable. — Manuel

It's vast to me and I straddle those two views. If I completely looked at dreams as a clear source of information about how I should act, what other people are like and doing, what I want and need, my life would be completely different. If you add to that difference different views of time, identity, morals, substance, causation you have very different views of the world. Yes, there is quite a variety of dogs and on the genetic level less so, at least how we prioritized differences (other cultures might not view all dogs as the same species, remember, so they might disagree with you). But the mind is vastly more flexible than the changes we've made through breeding canines.So the fact that some cultures take dreams to be more real than a culture which doesn't focus on dreams isn't as drastic as it looks, in my opinion. — Manuel

I've been fluent in my wife's language for 21 years. I live in her country. The languages are quite close. The cultures are quite close. I've worked with communciation in a diverse set of roles and have been used professionally for crosscultural communication roles also, and not just between her culture and mine, but there also.

And still we discover differences and confusions, some having to do with identity and and perception, to this day. Not the man woman stuff (though with that also), but cultural models. Throw me in with an Amazonian tribe with a still living shamanic tradition...and we'd be having to come back again and again to basic ontological investigations to undertand each other. -

Janus

18kbut materiality or form are a bit more dubious. — Manuel

Janus

18kbut materiality or form are a bit more dubious. — Manuel

I think form or shape is an inevitable category of understanding. Materiality refers to constitution, which also seems to be an inevitable concept if different materials are encountered.

I don't see why, say, a city would have to be a part of the cognitive architecture of another creature. A house? Maybe - at least territory, based on examples we see here on Earth. — Manuel

Perhaps not, unless it was a creature that builds cities, I guess. Again though, I'm not claiming that the same entities we conceive would be conceived by all symbolic species.

Take a look out your window, or next time you're out in a park, with plenty of trees and bushes around. Ask yourself, "how many objects are there here?" It soon becomes evident that we have a problem, we have a multiplicity of objects, but do we know how many? — Manuel

Yes, I agree, we have a multiplicity or number of objects, but we don't know how many. Apart from the practical problem of actually counting them what do we count as an object or entity? (Note the word 'count' here as also meaning 'to qualify').

With the example of the tree, we understand it to be a wholistic self-organizing organism, so I think roots, truck, branches and leaves all count as parts of the tree. But what about the Mycorrhiza (fungi) that attach to the roots symbiotically? They are generally not counted as part of the tree, even though they might die along with the rest of the tree if you poisoned the tree.

I have to go out now, so I'll try to respond to the rest of your post later, Manuel. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThe Sun is 93 million miles away from Earth, the distance remains a fact, irrespective of us. — Manuel

Wayfarer

26.1kThe Sun is 93 million miles away from Earth, the distance remains a fact, irrespective of us. — Manuel

Realism assumes that the world is just so, irrespective of whether or not it is observed. It may be a sound methodological assumption but it doesn't take into account the role of the observing mind in the establishment of scale, duration, perspective, and so on.

So, I question the notion that there are facts that stand 'irrespective of us'. We can establish distances, durations, and so on, across a huge range of scales, from the microscopic to the cosmic, which we can be confident will remain just so even in the absence of an observer. But even that imagined absence is a mental construct. There is an implied viewpoint in all such calculations. This is thrown into relief in quantum physics, but it's true across the scale. We're used to thinking of what is real as 'out there', independent of us, separate from us, but in saying that, we don't acknowledge the fact that reality comprises the assimilation of perceptions with judgements synthesised into the experience-of-the-world. -

Luke

2.7kYes, that's right. The 'feeling of pain' is not a reified object. It's a folk notion. It exists in that sense (like the category 'horses' exists), but there's no physical manifestation of it. — Isaac

Luke

2.7kYes, that's right. The 'feeling of pain' is not a reified object. It's a folk notion. It exists in that sense (like the category 'horses' exists), but there's no physical manifestation of it. — Isaac

When you say "the feeling of pain is not a reified object", it sounds like you're denying that people really have pains. The feeling of pain is not merely a learned concept, because pain hurts. Animals without linguistic concepts can be in pain, and we can sympathise with those in pain. Pains exist in the world, are real and are therefore 'reified', as much as horses are. The physical manifestations of pain are found in the behaviours of people and other animals.

Then how could we ever learn to use the word?

— Luke

By trying it out and it's having a useful and predictable effect. — Isaac

That might be the case if you had to learn language without anybody's help. A more common scenario is that, when first learning the language, others see you in pain (i.e. see your physical manifestations of pain) and teach you the meaning of the word when you experience it. "Oh did you hurt yourself?" "Where does it hurt?" "Do you have a tummy ache?" "Is your knee sore?" "Is it painful?"

As Wittgenstein suggests: "How does a human being learn the meaning of names of sensations? For example, of the word “pain”. Here is one possibility: words are connected with the primitive, natural, expressions of sensation and used in their place. A child has hurt himself and he cries; then adults talk to him and teach him exclamations and, later, sentences. They teach the child new pain-behaviour.

“So you are saying that the word ‘pain’ really means crying?” — On the contrary: the verbal expression of pain replaces crying, it does not describe it." (PI 244)

Yes. I find it philosophically interesting too. What I'm arguing against here is there being any kind of 'problem' with the fact that neuroscience (dealing with physically instantiated entities) cannot give a one-to-one correspondence account connecting these entities to the folk notions 'pain' and 'consciousness' (as well as 'feeling', 'it's like...', 'aware', etc).

It's not a problem because it's neither the task, nor expected of science to explain all such folk notions in terms of physically instantiated objects and their interactions.

Basically, because (2) is at least possible, there's no 'hard problem' of consciousness because neuroscience's failure to account for it in terms of one-to-one correspondence with physically instantiated objects may be simply because there is no such correspondence to be found. — Isaac

Assuming there isn't a one-to-one correspondence - and it seems likely there isn't - I don't see that the problem of subjective experience therefore disappears. Neither do I consider subjective experience to be merely a "folk notion" - again, pain hurts. Therefore, it seems to me that the lack of one-to-one correspondence only makes neuroscience's task of explaining subjective experience more difficult (assuming that it is a task for neuroscience, rather than some other branch of science). -

Manuel

4.4kRealism assumes that the world is just so, irrespective of whether or not it is observed. It may be a sound methodological assumption but it doesn't take into account the role of the observing mind in the establishment of scale, duration, perspective, and so on. — Wayfarer

Manuel

4.4kRealism assumes that the world is just so, irrespective of whether or not it is observed. It may be a sound methodological assumption but it doesn't take into account the role of the observing mind in the establishment of scale, duration, perspective, and so on. — Wayfarer

I mean, there are many, many versions of realism. The realism I think holds up is something akin to Russell's "epistemic structural realism": the notion that science captures only the structures of things in the universe, without telling us about its "internal constitution", to borrow Locke's phrase. It's a view which wouldn't deviate much from Kantianism.

which we can be confident will remain just so even in the absence of an observer. But even that imagined absence is a mental construct. There is an implied viewpoint in all such calculations. — Wayfarer

I can't deny that, because it's true. It is a mental construct, but something about mathematics, mediated by mind, when applied to certain aspects of the universe, tells us something that is not mental "only". If it were mental only, we would not be able to do Astronomy or tell how old the Earth is and so forth.

This is all mediated by mind, but there are glimmers that we are seeing something extra-mental. Having a degree of confidence is the best we can do, given the circumstances.

We're used to thinking of what is real as 'out there', independent of us, separate from us, but in saying that, we don't acknowledge the fact that reality comprises the assimilation of perceptions with judgements synthesised into the experience-of-the-world. — Wayfarer

No disagreement. By saying that math tells us something about the world absent us, I'm only echoing what Russell says, which you often quote. It's because we know so little about the world that we turn to math, it's not because we know a lot about it.

No rush at all Janus, it's all a fun exercise for the sake of thinking about how you view these things, which often helps me think more clearly too. I'll reply when you finish, which needn't be today, nor tomorrow, that way we don't break up the conversation. :up:

The ontological diversity is enormous. — Bylaw

That's the thing, I think you are describing epistemic differences, not ontological ones. Differences in the way we approach our views of the world, it's not a difference in the world itself. To put is simply, take a baby from anywhere in the world - your pick: place it in the most "far removed" culture you can think of in terms of beliefs and practices from the babies original culture, and that baby will grow up with the beliefs

of the "far removed" culture.

Let the baby grow, bring it back to it's birthplace - let it stay there a few months, maybe longer, they will be able to understand the differences quite well. It may initially seem like that person is experiencing "two different worlds", but it's not literally true. If it were, we wouldn't be able to do translation, or talk to each other in different languages, for instance.

I've been fluent in my wife's language for 21 years. I live in her country. The languages are quite close. The cultures are quite close. I've worked with communciation in a diverse set of roles and have been used professionally for crosscultural communication roles also, and not just between her culture and mine, but there also.

And still we discover differences and confusions, some having to do with identity and and perception, to this day. Not the man woman stuff (though with that also), but cultural models. Throw me in with an Amazonian tribe with a still living shamanic tradition...and we'd be having to come back again and again to basic ontological investigations to undertand each other. — Bylaw

I'm not denying these things - they are big differences in terms of how we view the world, that doesn't take away from my original claim: it's all within the human species.

Since we can't know anything "above" our species, so to speak, these differences will look (and feel) like substantial differences to us, we can't help feeling that way. But a more intelligent being would look at us as if we are the same species, with minor variations in behavior.

So I think our only point of potential disagreement is one of ontology vs epistemology. I think you're claims aim to be ontological, I think they are epistemological. -

hypericin

2.1kBasically, because (2) is at least possible, there's no 'hard problem' of consciousness because neuroscience's failure to account for it in terms of one-to-one correspondence with physically instantiated objects may be simply because there is no such correspondence to be found. — Isaac

hypericin

2.1kBasically, because (2) is at least possible, there's no 'hard problem' of consciousness because neuroscience's failure to account for it in terms of one-to-one correspondence with physically instantiated objects may be simply because there is no such correspondence to be found. — Isaac

After what, 100 posts on this topic? You demonstrate you have no clue what the hard problem is.

At least read this: https://iep.utm.edu/hard-problem-of-conciousness/#:~:text=The%20hard%20problem%20of%20consciousness%20is%20the%20problem%20of%20explaining,directly%20appear%20to%20the%20subject.

In more detail, the challenge arises because it does not seem that the qualitative and subjective aspects of conscious experience—how consciousness “feels” and the fact that it is directly “for me”—fit into a physicalist ontology, one consisting of just the basic elements of physics plus structural, dynamical, and functional combinations of those basic elements. It appears that even a complete specification of a creature in physical terms leaves unanswered the question of whether or not the creature is conscious. And it seems that we can easily conceive of creatures just like us physically and functionally that nonetheless lack consciousness. This indicates that a physical explanation of consciousness is fundamentally incomplete: it leaves out what it is like to be the subject, for the subject. There seems to be an unbridgeable explanatory gap between the physical world and consciousness. All these factors make the hard problem hard. -

Bylaw

559

Bylaw

559

Well, that's by definition, regardless of the closeness or vastness of the differences. I am not arguing that the differences between beliefs between human groups arenot []within the human species. That would be foolish. I was responding toI'm not denying these things - they are big differences in terms of how we view the world, that doesn't take away from my original claim: it's all within the human species. — Manuel

We are dealing with vague evaluations like 'superficial' but since the beliefs lead to such a vast range of behavior, I don't know how this can be claimed. You then went on, in the original post I responded to saying that other species must have a greater difference in ontology. This too seems beyond our know precisely as you mention we do not have language, but since the behaviors of these animals tend to fall into categories of behavior that humans also exhibit, but humans engage in categories of behavior and in a great range of diverse way, precisely to do language, inherited culture, opposable thumbs, etc., we can have, at least possibly or even probably a greater range of ontologies.Between human beings? Maybe, but the differences are superficial

You mentioned diversity amongst deities...

We don't have any reason to believe animals, say, think there are deities., let alone that sacrificing to them or abstaining from sex or letting the deity take over their bodies or eating their deity or wearing certain clothes when one is being sacred as opposed to profane and so on are good things to do.

My sense of the cognitve abilities and varitation within other species is probably on the fringe end that assumes we have long radically underestimated this, especially in the scientific community, but I still think that human ontologies include and go beyond the ontological categories animals have. Not because we are so great, but because we have the need, given the goals we have set up (based on some of our abilities).

If we are thinking of extra terrestrial life forms, perhaps one of the core attributes of advanced sentient primates is imagination and play. So we generate more diversity than this or that specific species or even sentient species in general. Perhaps it's mostly insect like hive group intelligences out there, with diversity seen as only a problem or not even quite conceivable. I don't know. I don't know how we could know.

Again, I don't know how you can know this. Two, they might be much more monocultural than us and find the diversity striking, obscene, confusing. I see no reason to rule that out. Also, there might be tendencies within sentient species and that sentient species might recognize a similar vast diversity to the one that they have in their own species.Since we can't know anything "above" our species, so to speak, these differences will look (and feel) like substantial differences to us, we can't help feeling that way. But a more intelligent being would look at us as if we are the same species, with minor variations in behavior. — Manuel

One of the current trends in anthropology is called the ontological turn. They have realized that categories have been projected onto other cultures and that anthropogists actually need to work on their own categories much more completely because they are not able to conceptualize what they are encountering. Their categories fail, but don't seem to. There are seeds of the change in older anthropology but this issue has become central. For example the descriptions of animism have been presented in categories that match the Western models, even if they deviate from them. Anthropologists have realized that they need to, often, create new categories, more or less black box ontology to even describe the other culture's beliefs and categories. And the focus is on ontology. Not just epistemological issues of how to understand what they mean.

But if your point is that all the variations of ontology, say, we find in humans is within the human species, well, I agree.

I am not sure what this would mean.So I think our only point of potential disagreement is one of ontology vs epistemology. I think you're claims aim to be ontological, I think they are epistemological. — Manuel

I think various groups have quite different ontologies and these lead to a wide range of behavioral differences. I don't see these differences as superficial. Yes, there is also a diversity of epistemologies. -

Janus

18kThe universe is 13.7 billion years old. Even when we all die, that fact will remain. That's the age of the universe, before we arose (maybe new theories will change this estimate or render it obsolete).

Janus

18kThe universe is 13.7 billion years old. Even when we all die, that fact will remain. That's the age of the universe, before we arose (maybe new theories will change this estimate or render it obsolete).

The Sun is 93 million miles away from Earth, the distance remains a fact, irrespective of us.

Now the colour of the sun, us seeing it rising in the East and setting in the West, the warmth we feel form it, and so on, these things will not hold up, absent us. — Manuel

I guess the question here for me is how meaningful is the idea that facts, which are given in anthropomorphic terms, will remain when we are gone. Where will they remain? This is a little like your question about where numbers are, except I think I'm coming from the opposite angle, so to speak. Your question seemed to assume that numbers must "be somewhere", since they don't seem to be mind-dependent.

I want to question the idea that they really are mind-independent, or even that time, change, diversity, identity and so on, are mind-independent. But the flip-side would be also to question the idea that the mind and mental phenomena are matter-independent, and further, to question the idea that there is any distinction between matter and mind apart from our human dualistic mode of thinking.

So, in short, I want to question the idea that anything "holds up, absent us". This would be to say that there is no-thing absent the conception of thing, but that what remains would not be nothing at all. This is in line with the idea that the real is neither something nor nothing, that those categories pertain only to our thinking, not to human-independent "reality". That's about as clear as I can make it, I'm afraid. I agree with Kant in that I'm not confident that it can be made any clearer. -

frank

19kThis is all mediated by mind, but there are glimmers that we are seeing something extra-mental. Having a degree of confidence is the best we can do, given the circumstances. — Manuel

frank

19kThis is all mediated by mind, but there are glimmers that we are seeing something extra-mental. Having a degree of confidence is the best we can do, given the circumstances. — Manuel

I don't think the glimmer of the extra-mental is seen anywhere. It's part of the structure of our worldview that we look out at a non-mental world. A few thousand years ago that would have sounded absurd. So the ground of your claim is cultural, right? -

Wayfarer

26.1kSo, in short, I want to question the idea that anything "holds up, absent us". This would be to say that there is no-thing absent the conception of thing, but that what remains would not be nothing at all. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.1kSo, in short, I want to question the idea that anything "holds up, absent us". This would be to say that there is no-thing absent the conception of thing, but that what remains would not be nothing at all. — Janus

:clap: This is very much the point I've been labouring (subject of my Medium essays.)

I will also re-iterate that I think the 'hard problem of consciousness' is not about consciousness, per se, but about the nature of being. Recall that David Chalmer's example in the 1996 paper that launched this whole debate talked about 'what it is like to be' something. And I think he's rather awkwardly actually asking: what does it mean, 'to be'?

(I've finally started reading some of Heidegger, and whilst I have not yet acquired a lot of knowledge about him, I do now know that his over-arching theme throughout his writings was 'the investigation of the meaning of being', and that he thinks this is something that we, as a culture, have generally forgotten, even though every person-in-the-street thinks it obvious. )

Anyway, Chalmer's selection of title is perhaps unfortunate, because it is quite possible to study consciousness scientifically, through the perspectives of cognitive science, experimental psychology, biology, neurology and other disciplines. But we can't study the nature of being that way, because it's never something we're apart from or outside of (another insight from existentialism.) In the case of the actual 'experience of consciousness', we are at once the subject and the object of investigation, and so, not tractable to the powerful methods of the objective sciences that have been developed since the 17th century. -

Paine

3.2kBut we can't study the nature of being that way, because it's never something we're apart from or outside of (another insight from existentialism.) In the case of the actual 'experience of consciousness', we are at once the subject and the object of investigation, and so, not tractable to the powerful methods of the objective sciences that have been developed since the 17th century. — Wayfarer

Paine

3.2kBut we can't study the nature of being that way, because it's never something we're apart from or outside of (another insight from existentialism.) In the case of the actual 'experience of consciousness', we are at once the subject and the object of investigation, and so, not tractable to the powerful methods of the objective sciences that have been developed since the 17th century. — Wayfarer

I read Chalmers to be saying that consciousness could be investigated as a scientific phenomenon if the 'powerful methods' stopped insisting upon reducing it into a mechanism that excludes the need for a 'subject.'. Chalmers says the only way to avoid the problem is to include consciousness.as a fundamental property like mass, space, time, etcetera. To that extent, he is arguing against a 'scientism' that accepts the Descartes/Kant divisions as a final word on what can be investigated.

I understand the viewpoints stated by many in this thread that dismiss his framework as philosophically suspect. I just don't want to lose sight of what he thought he was doing as a point of departure. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI read Chalmers to be saying that consciousness could be investigated as a scientific phenomenon if the 'powerful methods' stopped insisting upon reducing it into a mechanism that excludes the need for a 'subject.'. — Paine

Wayfarer

26.1kI read Chalmers to be saying that consciousness could be investigated as a scientific phenomenon if the 'powerful methods' stopped insisting upon reducing it into a mechanism that excludes the need for a 'subject.'. — Paine

But I agree - that's a different way of making the same point. What is the name for the human subject? Why, that is 'a being'. And the failure to grasp this fundamental fact is an aspect of what Heidegger describes as 'the forgetting of being'. I've had many a debate on this forum, some of them very bitter and acrimonious, because I claim that beings are fundamentally different from objects.

Elsewhere, Chalmers advocates, and Dennett dismisses as fantasy, the idea of a 'first-person science'. But, as has been pointed out, phenomenology was originally conceived by Husserl as a first-person science of consciousness.

So I disagree that my post 'looses sight' of Chalmer's point of departure. I'm simply saying that what he describes as 'the hard problem of consciousness' could be better depicted as the problem of the meaning of being. -

Paine

3.2k

Paine

3.2k

I don't mean to accuse you of losing sight of something but to suggest there is a gap between Husserl, for example, and Chalmers in regard to how the 'first person' is understood as the source of phenomena.

Chalmers is fighting for accepting methods of the first person as evidence in the face of the thinking/practice that has excluded them. Husserl is taking those experiences as given to him without qualification.

Heidegger is a voice of opposition to the 'scientism' he sees in society. Chalmers is militating against that view when he does not accept that science has nothing more to do with the matter of subjectivity. -

Wayfarer

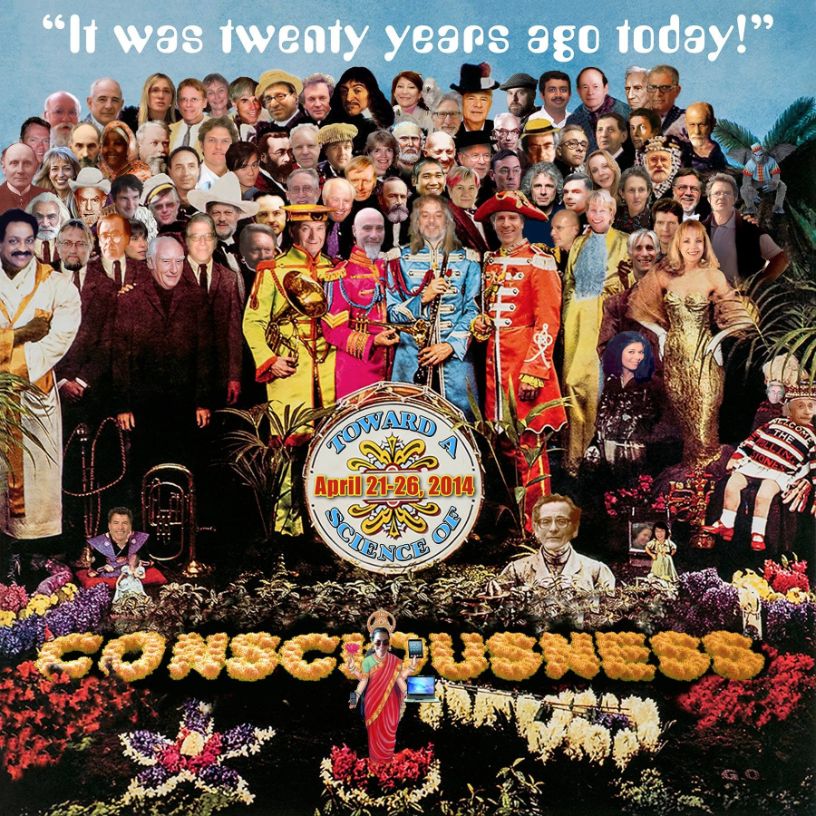

26.1kAll fair points. I agree that Chalmers himself is not a phenomenlogical analyst. But I think the philosophical dimension, however articulated, is what is easily lost sight of in all these debates (as the desultory nature of much of this thread illustrates.) Furthemore, Chalmers is part of a kind of new wave in 'consciousness studies' that is far more open to, shall we say, alternative philosophical models, than the diehards of analytical philosophy (as illustrated in this memorable poster for the 20th Anniversary Consciousness Studies conference:

Wayfarer

26.1kAll fair points. I agree that Chalmers himself is not a phenomenlogical analyst. But I think the philosophical dimension, however articulated, is what is easily lost sight of in all these debates (as the desultory nature of much of this thread illustrates.) Furthemore, Chalmers is part of a kind of new wave in 'consciousness studies' that is far more open to, shall we say, alternative philosophical models, than the diehards of analytical philosophy (as illustrated in this memorable poster for the 20th Anniversary Consciousness Studies conference:

From here https://consc.net/pics/tucson2014.html) -

Manuel

4.4kAgain, I don't know how you can know this. Two, they might be much more monocultural than us and find the diversity striking, obscene, confusing. I see no reason to rule that out. Also, there might be tendencies within sentient species and that sentient species might recognize a similar vast diversity to the one that they have in their own species.

Manuel

4.4kAgain, I don't know how you can know this. Two, they might be much more monocultural than us and find the diversity striking, obscene, confusing. I see no reason to rule that out. Also, there might be tendencies within sentient species and that sentient species might recognize a similar vast diversity to the one that they have in their own species.

One of the current trends in anthropology is called the ontological turn. They have realized that categories have been projected onto other cultures and that anthropogists actually need to work on their own categories much more completely because they are not able to conceptualize what they are encountering. Their categories fail, but don't seem to. There are seeds of the change in older anthropology but this issue has become central. For example the descriptions of animism have been presented in categories that match the Western models, even if they deviate from them. Anthropologists have realized that they need to, often, create new categories, more or less black box ontology to even describe the other culture's beliefs and categories. And the focus is on ontology. Not just epistemological issues of how to understand what they mean. — Bylaw

The alternative would be to say that the only intelligent species that could develop, must be like us in almost all respects - that seems to me quite unlikely.

I think the issue here is the scope of what you take ontology to be. I take ontology to be about the world - what's in the world. It's not what we take there to be in the world. Different forms of animism, or ways of thinking about time or relationships or ways to think about the identity of objects and community, are not things about the world, these are things we postulate on the world, hence epistemic. Epistemology is not limited to questions of, how do we know what we do? It also includes what we believe there is in the world, and in this respect, most of us have been quite wrong (literally wrong - not applicable to the world, but still valuable) for thousands of years.

So I take epistemology to be quite broader than issues concerning justification. And I try to make ontology about the world - this includes physics, for instance aspects of chemistry and perhaps biology. Anything beyond that would be closer to a "folk psychology" - a term I deeply dislike, because it makes it sound not serious, when it is very serious and important. Nevertheless, that's how the issue looks like to me. -

Manuel

4.4k

Manuel

4.4k

Sure, I do think something existed prior to us. We know a few facts about it - not too too much, but not trivial information either.

Ok, so we have the same meaning of terms. So what's extra mental, like, if you look outside your window or go woods or something - what's extra mental in this environment? -

frank

19kOk, so we have the same meaning of terms. So what's extra mental, like, if you look outside your window or go woods or something - what's extra mental in this environment? — Manuel

frank

19kOk, so we have the same meaning of terms. So what's extra mental, like, if you look outside your window or go woods or something - what's extra mental in this environment? — Manuel

"Extra mental" would be anything that's beyond mental. It's an idea, not something you witness with your eyeballs. -

Manuel

4.4k

Manuel

4.4k

So you think the stuff physics describes wouldn't exist if we were absent? That is, there would be no such thing as an age of the universe, nor would there be things we call planets (after we arise and call them this) and events that led us to our evolving?

How do we account for these facts? -

frank

19kSo you think the stuff physics describes wouldn't exist if we were absent? That is, there would be no such thing as an age of the universe, nor would there be things we call planets (after we arise and call them this) and events that led us to our evolving? — Manuel

frank

19kSo you think the stuff physics describes wouldn't exist if we were absent? That is, there would be no such thing as an age of the universe, nor would there be things we call planets (after we arise and call them this) and events that led us to our evolving? — Manuel

Notice that in your previous comment, you added the caveat that our theories may have to be revised. Physics is in such a state that we really don't know how far from reality our intuitions are.

That means your claim pretty much reduces to: there is non-mental stuff that preceded us. That's not a conclusion drawn from any facts. It's an interpretation that's rooted in our present worldview. -

Manuel

4.4k

Manuel

4.4k

I have in mind post-Newtonian physics. They weren't proved wrong, they were shown to be inadequate to explain certain phenomena: the orbit of Neptune and a few other oddities.

So far as we know, spacetime has not been shown to be wrong, but it has not been able to be combined with quantum theory, which has also not been shown wrong.

When I say revisions, I have more in mind what kind of stuff may lie beneath quantum theory, or what is it that combines General Relativity with Quantum Mechanics.

I don't think these theories will be shown to be wrong (as was the case with Newton's theories), but obviously incomplete.

All I'm saying is that I don't think the universe depended on us for it to happen, it just is, and we manage to capture a little bit about it.

The alternative is that we created everything, including the world and that all we know are our ideas and nothing else. That's an extreme form of Berkelyianism. -

frank

19kI don't think these theories will be shown to be wrong (as was the case with Newton's theories), but obviously incomplete. — Manuel

frank

19kI don't think these theories will be shown to be wrong (as was the case with Newton's theories), but obviously incomplete. — Manuel

We might be in a black hole. Physics isn't slightly incomplete. It's very incomplete. Physics doesn't indicate any particular ontology.

The alternative is that we created everything, including the world and that all we know are our ideas and nothing else. That's an extreme form of Berkelyianism. — Manuel

Plato would say we forget most of the Soul's wisdom when we're born. There are all sorts of alternatives. There's nothing wrong with our present worldview. It works well for us. But there's no telling what people will believe in a thousand years. -

Manuel

4.4k

Manuel

4.4k

That's true, we don't know what 95% of the universe is made of, "only" 5% of it - which, given the species we are, is still a tremendous achievement.

Since the birth of modern science, with Galileo, Copernicus, Descartes and Newton we have been on a path of ever more precise identification of the structures of the universe: planets, asteroids, starts and so on.

Since Newton at least, physics has not been wrong, it has been improved. How far will that go? We don't know. Maybe we will stay stuck where we are, given practical limitations of technology and the vast distances involved between galaxies.

But if we are in black hole, then black holes exist, absent us. Planets do too. That doesn't depend on mind, though it was discovered by it. So planets and stars, are part of the ontology of Astronomy, subject to refinement, such as the case with Pluto.

Plato would say we forget most of the Soul's wisdom when we're born. There are all sorts of alternatives. There's nothing wrong with our present worldview. It works well for us. But there's no telling what people will believe in a thousand years. — frank

If we get that far. Yes, we don't know. But we are not too far from reaching the practical limitations I mentioned.

But that we create the manifest properties, when say, we look at images of James Webb, can only leave one in utter awe, at the power of our minds and the beauty they reveal (to us) about how the universe looks to us. So yes, we know very, very little. But not nothing, I wouldn't argue. -

Bylaw

559

Bylaw

559

I don't think that's what I'm saying. In fact I gave examples of species that were not like us, just not in the way you assumed. Further that species could be different in wide set of ways. Nowhere am I assuming what other alien species will have for ontologies that they've considered or subgroups on their world(s) have as their base. You're the one assuming that the range of our ontologies is superficial. And based on what you assume would be the case if we met another sentient civilization.The alternative would be to say that the only intelligent species that could develop, must be like us in almost all respects - that seems to me quite unlikely. — Manuel

The ontologies on earth have a greater range than those supported here on this forum and the other two philosophy forums I participate in. IOW the range of -isms is more diverse than the members have, and the struggles in defense and critique of these -isms is not taken as superficial by most of the participants. Many are considered foolish and dangerous or societally problematic and so the discussion is important to the members. The only players involved in these discussions tend not to think the differences are superficial and they're not enountering the diversity out there in the world. The only player to have subjective reactions like the sense these are profound or superficial differences.

Superficial is a subjective term, but it more or less entails a comparative assertion. The world's range of ontologies is superficial, despite the fact that experts in the field of discovering what this range is have decided that too often they have placed the ontologies they encountered in boxes that were not suitable for them. Projecting their own culture's ontology on those they encountered and already the diversity was enormous.

So, what is the comparison to. What isn't superficial? The ontologies of an alien race that we have not encountered. The vast range of that group's ontologies makes our range superficial or the differences are superficial. Maybe. Maybe not. I don't make an assumption about that. I don't know if sentient species, if they are separated into subgroups and also if some subgroups allow for those sentient beings to come up with their own ontologies and allow for very diverse lifestyles and experiences, will tend to come up with ranges of similar magnitude to other sentient species. I don't know if one of the characteristics of our minds makes us more likely to create and imagine a wide range of ontologies (and other stuff) whereas other species, tend to be more conservative with such things. I don't know. Which I've said a few times.

You seem to know. You found your assessment that the differences are superficial on something you don't know. It's not an unreasonable speculation on your part. But it's using as evidence something that you also don't know.

I notice myself repeating points that haven't been responded to, and also being told I am assuming things I'm not, so, I think we've probably reached an impasse. It's also a tangent from the main theme of the thread, so I'll leave the issue here. -

Janus

18kI will also re-iterate that I think the 'hard problem of consciousness' is not about consciousness, per se, but about the nature of being. Recall that David Chalmer's example in the 1996 paper that launched this whole debate talked about 'what it is like to be' something. And I think he's rather awkwardly actually asking: what does it mean, 'to be'? — Wayfarer

Janus

18kI will also re-iterate that I think the 'hard problem of consciousness' is not about consciousness, per se, but about the nature of being. Recall that David Chalmer's example in the 1996 paper that launched this whole debate talked about 'what it is like to be' something. And I think he's rather awkwardly actually asking: what does it mean, 'to be'? — Wayfarer

:up: The only issue I see with Chalmers proposal regarding a "new kind of science"; and that the subjective nature of consciousness might be understood and explained scientifically is that there doesn't seem to be the remotest idea of what such a science could look like.

I mean since scientific observations are publicly available whereas consciousness is not publicly observable it's hard to see how it could work. And you seem to be making pretty much the same point. So, I see the whole notion of pursuing a scientific investigation of first person experience as being a fool's errand. I think it should be renamed "the impossible problem" because the idea that it is a problem is a category error. We shouldn't expect science to be able to investigate and understand everything about human life, so it's not a failing of science so much as a failure to understand the limitations of science. -

Wayfarer

26.1kCan’t possibly disagree. I guess someone in Chalmer’s role *has* to couch it in those terms to maintain some kind of credibility for the mainstream audience. Actually I’ve been reading a bit about David Chalmers, including an interview with him - he’s married to another academic, who has two PhDs; he was a Bronze Medallist at the International Mathematics Olympiad before becoming a philosopher; his mother ran a spiritual bookstore. Overall, it sounds he has one helluva life. Oh, and overall I far prefer him to Jacques Derrida. :-)

Wayfarer

26.1kCan’t possibly disagree. I guess someone in Chalmer’s role *has* to couch it in those terms to maintain some kind of credibility for the mainstream audience. Actually I’ve been reading a bit about David Chalmers, including an interview with him - he’s married to another academic, who has two PhDs; he was a Bronze Medallist at the International Mathematics Olympiad before becoming a philosopher; his mother ran a spiritual bookstore. Overall, it sounds he has one helluva life. Oh, and overall I far prefer him to Jacques Derrida. :-) -

Wayfarer

26.1kRight, although he’s long since cut his hair.

Wayfarer

26.1kRight, although he’s long since cut his hair.

The more serious issue is that of explanatory frameworks. You and I have often discussed that, and I seem to recall you often saying that science is really the only credible public framework for such discussion, with other perspectives being designated 'poetic' - noble and edifying but essentially personal. But then, I guess that's part of the cultural dilemma of modernity, of which Chalmers and Dennett are two protagonists.

I've just been perusing the book from which the oft-quoted expression of 'Cartesian anxiety' is drawn. It is a 1986 book 'Beyond Objectivism and Relativism: Science, Hermeneutics and Praxis', by Richard J Bernstein (only died July last, see this touching obituary). It's a hell of a slog, but I think I'll persist with it, as it addresses just these themes from a cosmopolitan point of view - his main foils include Gadamer, Habermas and Hannah Arendt so he's not solely focussed on the Anglosphere (which is by and large a philosophical wasteland in my view.)

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum