-

Deleted User

0Philosophy has had a notorious history of knocking down rather intuitive concepts and social/intellectual ivory towers. There have always been anti-realists for every statement a realist gives along with a skeptic there to degrade both of them at once. Personally I’ve desired so strongly in the past couple of years and especially in the past few months to go back into the cave of some comfortable naïve scientific realism. However, the approaches of scientific anti-realists and dissident non-mainstream physicists/philosophers bring up points with which such a carefree delusion is not without explicit intellectual self-harm.

Deleted User

0Philosophy has had a notorious history of knocking down rather intuitive concepts and social/intellectual ivory towers. There have always been anti-realists for every statement a realist gives along with a skeptic there to degrade both of them at once. Personally I’ve desired so strongly in the past couple of years and especially in the past few months to go back into the cave of some comfortable naïve scientific realism. However, the approaches of scientific anti-realists and dissident non-mainstream physicists/philosophers bring up points with which such a carefree delusion is not without explicit intellectual self-harm.

When it comes to naïve views of scientific advancement it would be rather foolhardy to suppose that modern science, or its descendants, weren’t strong social enterprises intent on pushing both certain political agendas or mere technological tools of our economy. Science as truth, as another poster pointed out, is rather misplaced a notion as it seems that pragmatic notions of science have taken on greater popularity or swing. Usually incorporating some sense of empirical adequacy as king and other secondary notions of scientific value such as: Simplicity, restriction of counterfactual possibilities, unificationism, ‘world management’. However, empirical adequacy, let alone Truth, is in many cases left to the wayside especially when one thinks of how every scientific ‘theory’ is really a rather simple collection of metaphorical/linguistic descriptions or stories, an abstract logical/mathematical model, and a collection of physical analogue models which are usually rather picture-esque. You could suppose that for any observation or phenomenon you could change any one of those three parts or do it all at once and not step on the toes of falsificationism. In that sense, asking for whether a physical analogue model (billiard balls, ball-spring models, fluid models, etc) or a metaphorical philosophical interpretation of a theory is ‘true’ or even falsifiable is to ignore their observation independent purpose/use.

While colloquial science is renowned for its empirical successes this is seen by many dissidents as merely propping up technological development and ‘trial & error’ for what should be true scientific explanations/understanding of the world. Anyone can observe a pen fall, tell us how fast it falls, repeat this experiment, and mathematically model it but something seems lost in it all. What are the causally responsible actors here? How can we explain this in a way that seems ‘satisfiable’, intuitive, and true to the spirit of that naïve scientific picture?

The answers that both dissidents and renowned scientists have propagated, sometimes quoted as proof, seem entirely in contrast to modern day relativistic/quantum language which have almost nuked intuitive physical analogue modeling. In its replacement we may find ourselves un-explanatory mathematical equations, reification of terms of highly abstract natures (such as: fields, energy, mass, motion, spacetime, etc), or apparently irrational metaphorical explanations which use intuitive words in non-traditional manners without a clear visual picture to speak of. Tons of modern day scientific literature both college level, documentary stylized, or from the high echelons of physics disciplines can be seen as rather renowned for their throwing around of terms such as field/spacetime/mass/momentum/motion/etc. Resulting in cases where it's difficult to know whether they mean an electric field to be the mathematical model they are using, the phenomenon they are dealing with, or the noumena that gave rise to said phenomenon. Further, even in attempting to correct that language with some philosophical education on terminology and consistency there still remains a question of, if one that is to be seen as problematic at all, of whether an explanation/understanding of a phenomenon is one of mostly non-visual metaphorical/mathematical approaches or visual mechanistic ones.

Such a mechanistic picture-esque view of the world is one which has held a strong grip on Classical physics as the corpuscular-kinetic models of the world reigned supreme for centuries in line with their Aether cousins. Their intuitiveness makes any slight attempt at change be declared as un-scientific or be seen as somewhat occultist. Action-at-a-distance in the case of electricity/gravity was declared as an illusory notion given some unseen mediators or the natural Aether vorticial motion of larger bodies. The liquid nature of all bodies, including the Aether itself in some cases, was declared as a result of only observing a large aggregate of atomic constituents. Only the intrinsic properties of solidity and extension were really ascribed to such entities while all others were derivative. Hot or cold is just faster/slower motions of these smaller parts. Time and change being defined as relative to their constantly shifting configurations. You can’t falsify them because physical analogue models make no predictions as only mathematical models with some loose observational fitting do which can always have a corpuscular model fitted to it even if it's rather rough indeed.

To get at this a different way, think of the idea of the universe possessing a non-Euclidean spherical geometry. Such a notion, with the advent of modern geometrical axiomatic approaches, doesn’t seem to be such a peculiar proposition but in principle it's technically un-imaginable to us. The best we can do is try to make analogies to ants moving on spheres which seem to get some of the ideas of what that non-Euclidean geometry seems to be while misleading us because of the 3-d immersion. We could even imagine a physically tangible scenario and still come to alternative explanations which seem more realizable despite their added, seemingly ad hoc, physics adjustments.

Imagine you see a person in a spaceship speed away from you in what seems a straight direction but after some time they return as if they went in one wide circle. At first they may declare the world non-Euclidean after all and also of possessing a spherical topology. However, one could in fact imagine rather easily that the spaceship in question didn’t travel in some strange higher dimensional loop but merely made a roundabout turn in ordinary Euclidean 3-space. All observations and light warping they saw in front or behind could be attributed to different ways that light in fact actually follows curved trajectories rather than straight geodesics on a 3-sphere. A rival physicist will contend this seems rather ad hoc and excessive for nature to trick us this way but any person supposing the former re-interpretation could say that their idea of how this took place would seem too easily grasped to be so wrong-headed. They may even contend that this rival physicist is more irrational or obscure in his suggestions as his 3-sphere concept of the universe isn’t intended to be visualized at all and perhaps only through metaphor or math can it be expressed. At that point it would seem as if they may in fact be playing a game of poetry which yields no transcendental insight except one of pure nonsense. Like supposing there are square circles in virtue of the fact that one could fit the word ‘square’ in a sentence before the word ‘circle’ then imply it means anything but pure nonsense.

I'm curious as to how one would defend the use of any non-visualized type of language or mathematics together with an insistence that despite its un-intuitiveness it still has a place in scientific explanation/understanding. A place that isn't merely description or that it could be argued away as some misuse of concepts to generate nonsense statements.

Do you think that modern physics, or even philosophy in general, has gone off the rails with regards to non-visualized poetry/metaphor and abstract obsessions? Or is there some way to lean into non-visualization through metaphor or mathematical modeling but without an occultist taste to it? Should we go back to a highly mechanistic picture of the world in scientific education/philosophy regardless of what those analogue models may specifically be? -

Wayfarer

26.1kA couple of observations made off the top of my head.

Wayfarer

26.1kA couple of observations made off the top of my head.

It seems to me it's been written from a perspective of a kind of disillusionment, by someone who formerly believed that the role of science was to develop a true picture of the world, but has now come to see that this seems increasingly remote. So that even though you say you've seen through naive or scientific realism, you're still not really able to let it go, or see what could replace it. You seem to be expressing a fear that, if you completely let go the mechanistic world-picture, then (heaven knows) anything goes.

Anyone can observe a pen fall, tell us how fast it falls, repeat this experiment, and mathematically model it but something seems lost in it all. — substantivalism

Odd choice of an example object. One usually picks 'a billiard ball' or some other simple object - of course it is true that pens will fall at the same rate as billiard balls, all things being equal, but pens are primary for communication, and physical predictions of how it will behave when dropped will tell you nothing about what you might write with it when you pick it up. I think perhaps that your choice of metaphor here is an inadvertant expression of the problem you're grappling with!

Or is there some way to lean into non-visualization through metaphor or mathematical modeling but without an occultist taste to it? — substantivalism

Again, there seems a kind of fear at work, that letting go the scientific outlook will result in devolution into some kind of voodoo magic. I also notice your mention of Capital T Truth. But I don't think science is about that - certainly, philosophy as taught in the English-speaking academy is not. I think you feel a kind of longing for a unitive vision, a sense in which everything will hang together or make sense, but it's diabolically difficult in the modern world to arrive at that, now that everything is so specialized, and there are such vast amounts of information available.

One book I've been studying which might be of assistance to your quest is Incomplete Nature by Terence Deacon. He attempts to account for intentionality within a naturalist framework, although it's a pretty tough read. But a romantic or mystic, he ain't.

Me, I'm more drawn to classical philosophy (as well as philosophical spirituality), although it's taken me a lifetime to begin to understand it. But I'm realising the richness of our Platonic heritage, and I would recommend to anyone looking at Plato again. Also reading philosophy in a synoptically and historically - trying to form a picture of the way in which the subject started and developed through the history of ideas.

Of particular importance to the kinds of questions you're asking would be the metaphysical assumptions behind the advent of science (e.g. this). And also philosophy of science - Kuhn, Feyerabend and Polanyi. They can help re-frame the issue, such that the distinct difference between the philosophical and purely scientific perspectives comes into view.

That's about all for now, but you're into a lot of really big questions in all that. -

Deleted User

0

Deleted User

0

You are not wrong in that assessment. In my life I have few interests and fewer things to be proud of in their stability as well as their personal meaningfulness. However, the deflationist and deconstructivist views of others upon all philosophy, but especially scientific thought, has resulted in a rather bitter view to it all.It seems to me it's been written from a perspective of a kind of disillusionment, by someone who formerly believed that the role of science was to develop a true picture of the world, but has now come to see that this seems increasingly remote. — Wayfarer

Its more a natural bias as the mentality of laymen including myself is to make recourse to authorities and minds that are supposed to reveal deep truths about the world. The second you realize they weren't doing any better than you, in certain philosophical respects, it sort of screams of a certain ill-fitting title of 'genius' or 'Nobel physicist'. Once that respect is lost. . . where am I supposed to turn to?So that even though you say you've seen through naive or scientific realism, you're still not really able to let it go, or see what could replace it. You seem to be expressing a fear that, if you completely let go the mechanistic world-picture, then (heaven knows) anything goes. — Wayfarer

Also, yes. . . in a sense this bid against realism of a scientific sort seems to threaten to dismantle not just those intellectual domains but also great social ones. What would you expect if you let epistemological anarchism into the greater social sphere? I feel its rather obvious the fear this instills and the deep desire to push back against this whether this means to back track or forcefully move on to other avenues of thought.

I used it rather arbitrarily but did not come to think of it in the manner you are presenting.Odd choice of an example object. One usually picks 'a billiard ball' or some other simple object - of course it is true that pens will fall at the same rate as billiard balls, all things being equal, but pens are primary for communication, and physical predictions of how it will behave when dropped will tell you nothing about what you might write with it when you pick it up. I think perhaps that your choice of metaphor here is an inadvertant expression of the problem you're grappling with! — Wayfarer

Its not only difficult in its attainment but its also a disease of the mind that infects not only those of the highest physics esteem to the greatest critical dissidents of the Mainstream. Everyone seems to want to create a unified picture of the world in the simplest terms. . . fewest symbols. . . fewest meanings. . . no matter the contradictory consequences.Again, there seems a kind of fear at work, that letting go the scientific outlook will result in devolution into some kind of voodoo magic. I also notice your mention of Capital T Truth. But I don't think science is about that - certainly, philosophy as taught in the English-speaking academy is not. I think you feel a kind of longing for a unitive vision, a sense in which everything will hang together or make sense, but it's diabolically difficult in the modern world to arrive at that, now that everything is so specialized, and there are such vast amounts of information available. — Wayfarer

I have been looking into this from the purview of other philosophical lines of thought. More specifically that of Carnap and a modern day reemergence of his internal/external distinction in meta-philosophy but not founded on the analytic/synthetic divide. Instead, my own interests have turned in the direction of metaphor to support this deflationist view of philosophy in terms of a literal/figurative divide. I've also just read a book by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson that attempted to skirt the rationalist/empiricist divide as well as potentially other such divides on the back bone of metaphor itself rather than attempting to, as is the case in literalist traditions of analytic philosophy, to rid ourselves fundamentally of metaphorical speech.One book I've been studying which might be of assistance to your quest is Incomplete Nature by Terence Deacon. He attempts to account for intentionality within a naturalist framework, although it's a pretty tough read. But a romantic or mystic, he ain't.

Me, I'm more drawn to classical philosophy (as well as philosophical spirituality), although it's taken me a lifetime to begin to understand it. But I'm realising the richness of our Platonic heritage, and I would recommend to anyone looking at Plato again. Also reading philosophy in a synoptically and historically - trying to form a picture of the way in which the subject started and developed through the history of ideas.

Of particular importance to the kinds of questions you're asking would be the metaphysical assumptions behind the advent of science (e.g. this). And also philosophy of science - Kuhn, Feyerabend and Polanyi. They can help re-frame the issue, such that the distinct difference between the philosophical and purely scientific perspectives comes into view. — Wayfarer -

Deleted User

0@Wayfarer Despite the appeal and curiosity I hold to that approach of Lakoff and Johnson it doesn't seem to assuage the worry within of deeply misleading myself. An objectivist who says, "There is a fundamental language, perspective, and methodology out there but you choose to ignore it as you settle for intellectual hedonism of various sorts."

Deleted User

0@Wayfarer Despite the appeal and curiosity I hold to that approach of Lakoff and Johnson it doesn't seem to assuage the worry within of deeply misleading myself. An objectivist who says, "There is a fundamental language, perspective, and methodology out there but you choose to ignore it as you settle for intellectual hedonism of various sorts."

I have also been intending to read into this long article on threats of Naturalism and quietism to natural philosophy. Something that hopefully showcases the biases inherent in what were supposed to be rather neutral theses but rather are not as nuanced as they appear to be.

Milič Čapek has been helpful here as well in that his collection of papers from others on the concepts of space and time as well as his E-book on the philosophy of physics seem to showcase the assumptions in thought that form Mechanistic physics. A peculiar world view that always seems to be removed from the clear definitions of others but pervades all of Classical physics and it also seems that those biases died hard when coming into modern physics. You may even say they are still rather prevalent despite the apparent 'transcendence' of physics disciplines from such thinking.

Particularly with regards to metaphors such as time as a substance and time as a film strip. I.E. that time is similar to a solid block without change or movement only mere spatial juxtaposition of its internal parts to each other. . . not some temporal sense of sequential following. That time is composed of fundamentally unchanging eternal 'instants' which either flash by out of existence or become non-real in a different sense. In that they are not 'projected' or lit up in the film analogy. Temporal metaphors such as time as a river or time as change are much more difficult to wrap ones head around and to theoretical physicists their worth seems next to nothing as they exude no easy mathematical/abstract/predictive avenues. Ergo, they are declared as poetic and handwaved away. -

Wayfarer

26.1kA peculiar world view that always seems to be removed from the clear definitions of others but pervades all of Classical physics and it also seems that those biases died hard when coming into modern physics. You may even say they are still rather prevalent despite the apparent 'transcendence' of physics disciplines from such thinking. — substantivalism

Wayfarer

26.1kA peculiar world view that always seems to be removed from the clear definitions of others but pervades all of Classical physics and it also seems that those biases died hard when coming into modern physics. You may even say they are still rather prevalent despite the apparent 'transcendence' of physics disciplines from such thinking. — substantivalism

Here's a big-picture sketch of how I interpret the whole issue of mechanistic materialism and its demise at the hands of the new physics. The advent of Newtonian physics and Galilean astronomy posited a sharp division between the subjective and objective domains, with the objective domain being defined solely in terms of the 'primary attributes' of physics - measurable quantities such as mass, velocity, and the like. The 'subjective domain' - that of mind - was associated with the 'secondary attributes' of color, taste, and so on, and was associated with Descartes 'res cogitans'. It was conceived as a completely separate substance (or type of being), another aspect of this proposed separateness. With all this came the birth of a new form of awareness, an 'objective consciousness', which sought to understand the Universe solely in objective and physical terms. That reached its clearest contemporary expression with positivism, as you mention, with Carnap as one of its chief exponents.

That approach has yielded enormous benefits in technical and scientific terms. But its shortcoming was precisely that it excluded the subject, who after all was the instigator and beneficiary of the entire panorama, from the picture! There was no place in it for h.sapiens, save as the 'outcome of the accidental collocation of atoms', as Bertrand Russell put it.

Many factors have begun to call that picture into question, not least the 'Copenhagen interpretation' of modern physics, which found that the observer could not be sharply divided from the observed after all - and in physics, the hardest of the so-called 'hard sciences'! Physicist John Wheeler, commenting on one of the experiments which indicated this problem, said:

The dependence of what is observed upon the choice of experimental arrangement made Einstein unhappy. It conflicts with the (realist) view that the Universe exists "out there" independent of all acts of observation. In contrast Neils Bohr stressed that we confront here an inescapable new feature of nature... In struggling to make clear to Einstein the central point as he saw it, Bohr found himself forced to introduce the word "phenomenon". In today's words Bohr's point - and the central point of quantum theory - can be put into a single, simple sentence. "No elementary phenomenon is a phenomenon until it is a registered (observed) phenomenon". It is wrong to speak of the "route" of the photon in the experiment of the beam splitter. It is wrong to attribute a tangibility to the photon in all its travel from the point of entry to its last instant of flight. A phenomenon is not yet a phenomenon until it has been brought to a close by an irreversible act of amplfification such as ...the triggering of a photodetector. In broader terms, we find that nature at the quantum level is not a machine that goes its inexorable way. Instead, what answer we get depends on the question we put, the experiment we arrange, the registering device we choose. We are inescapably involved in bringing about that which appears to happen.

All of this is, of course, subject of enormous commentary and speculation. I found Paul Davies' books especially useful in getting a clearer picture of it, but there are many others.

I glanced at the link you provided about naturalism, which looks interesting, but it's a book, and I have more than enough on my hands at the moment. But as it mentions Wittgenstein, I thought you might find this magazine article on Wittgenstein relevant - it was was originally published by the British Wittgenstein Society so its provenance is established: Wittgenstein, Tolstoy and the Folly of Logical Positivism. -

Deleted User

0@Wayfarer I'm shaking right now and have tears streaming down my face as thinking on all this has driven me to an emotional self-revelation. I'm not so sure if its the same for others and I should not speak on it as to defame them or ascribe to them what is not intrinsic.

Deleted User

0@Wayfarer I'm shaking right now and have tears streaming down my face as thinking on all this has driven me to an emotional self-revelation. I'm not so sure if its the same for others and I should not speak on it as to defame them or ascribe to them what is not intrinsic.

Within all positions, fears, and philosophies there is something we are striving for/against that we could not attain/fight through other means. There is much in my life that feels so. . . written in stone. So much minor suffering and monotony that I strive to repress it lest it destroy this being I call me. I asked myself a series of questions while looking over that Wikipedia link you gave. Why would I be so antagonistic towards religion, spirituality, mysticism, and the esoteric thinking of modern physicists? Is it all from a place of astute observations mixed in with critical reflections on the veracity of these claims? A question of lazy social engineering and indoctrination? Perhaps. . .

However, maybe the answer is more existential. I desire control of my surroundings as they are in most cases un-yielding. On and on again my days pass as those Humean patterns of causally apparent truth make it so clear. I have neither the will, methods, or know-how to influence them so they remain so un-yielding. Its similar to a learned sense of helplessness which compounds to a point that all of nature seems content on being so externally malevolent. So therefore I've either forgotten or never had some experience of the creativity and ingenuity that certain philosophers showcase. One that leaves open the door to a narrow path into something obscure.

Its an emotional realization of that fascination with which people gravitate towards fantasies of various sorts whereby the mere will of a passerby and a carefully chosen collection of spoken words a solution of esoteric origins will slay the monster or whisk one off the ground to safety.

I desire to bear witness to at least one such true miracle with which the shackles of objectivity and that learned sense of helplessness can be undone by its mere presence. However, as far as my experience goes, no such miracles have made their presence known to me. So it all bears down on me from the personally mundane to the scientifically sound. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI’d suggest not trying to hang on to it. These moments come and go, it is the intensity of the underlying enquiry which is key.

Wayfarer

26.1kI’d suggest not trying to hang on to it. These moments come and go, it is the intensity of the underlying enquiry which is key. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

Perhaps 17th century "classical" physics did initiate a clean break from its predecessor --- Christian theology --- by insisting on "hard" (orthodox ; on the rails) science, free from metaphorical language and metaphysical implications. But then, 20th century physics took a turn back toward softer philosophical methods, which use symbols & analogies to describe things & systems that are too complex, abstract, or entangled for the simplifying human mind to deal with. The early Quantum physicists, in particular, were perplexed by the "weirdness" of their sub-atomic physics experimental results.Do you think that modern physics, or even philosophy in general, has gone off the rails with regards to non-visualized poetry/metaphor and abstract obsessions? — substantivalism

So, they turned to philosophical metaphysics and Eastern religious tropes for poetic words*1 (quantum contextuality) to describe the non-particular & non-mechanical behaviors of energy & matter within the invisible foundations of reality. That "off the rails" departure from mechanical explanations was quickly labeled "quantum mysticism", and "anti-science". But, that was just a brief phase in the history of modern physics, as its hard technology products became profitable, and the mushy poetry was devalued. Consequently, hard-nosed scientists were taught to ignore the metaphorical mysteries and "just calculate".

Are you longing for a return to a softer kind of science, or maybe a more poetic brand of philosophy*2? Your screename, "Substantivalism"*3, harks back to the ancient roots of modern science in debates about the substance of reality. Greek Atomism was a good start toward a mechanistic worldview, except that it postulated no empty space for change, because nothingness was taboo. Yet, mechanism requires both hard stuff (substance) and soft space (relation) to produce a dynamic material & physical world that won't stand still for us to examine it.

The Mechanical imagery of ancient natural philosophy helped to simplify the complexities & mysteries of reality. But it omitted a role for the observer & manipulator of squirrely squirming quantum systems. Nonetheless, that voided vacancy was discovered by the quantum "mystics" as they groped in the spooky darkness of the unseen realm, where causation seemed to propagate its relationships instantly across empty space..

If that's what this thread is all about, you will find some sympathetic ears, but be prepared for accusations of preaching mystical "obsessions" and metaphysical woo-woo. :smile:

*1. Poetry as a Quantum Phenomenon :

Another quantum effect one sees in poetry is what’s called quantum contextuality. In terms of language, this simply means that a word’s meaning changes depending on the words that it’s entangled with.

https://northamericanreview.org/open-space/8263-2

*2. Metaphors We Live By is a book by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson published in 1980. The book suggests metaphor is a tool that enables people to use what they know about their direct physical and social experiences to understand more abstract things like work, time, mental activity and feelings. ___Wikipedia

*3. Substantivalism vs Relationalism

About Space in Classical Physics

https://shamik.net/papers/dasgupta%20substantivalism%20vs%20relationalism.pdf -

Deleted User

0

Deleted User

0

I'm not exactly sure. . . part of my journey here into these other works is motivated not by undoing the whole hardness of science nor is it entirely to soften it into poetic verbiage with merely aesthetic qualities. Perhaps, its more a research question as to whether there is some way to intuitively hold onto those poetic perennial forms of philosophy without succumbing to the same critiques from the 'shut up and calculate' crowd.Are you longing for a return to a softer kind of science, or maybe a more poetic brand of philosophy*2? — Gnomon

Again, take the example of non-Euclidean geometry. This would seem to be rather fully accepted and straight forward vernacular of a well founded, rational, modern scientific theory but perhaps there is a sense of how the establishment has glossed over any arguments as to its true intuitiveness. Arguments which don't found themselves on 'proof' or 'falsification' as those requirements have been shown to hold no water in the debate over philosophical 'obviousness'. Interpretations are a dime a dozen and claims as to the true 'spatialization of time' because a well founded theory is currently 'accepted' are non-starters.

However, that did not stop the mechanistic theories of Classical physics of accepting such an entity, as that book by Milič Čapek supports, and that there are more concepts that such a view of the world accepted than is usually let on. Such a Classical view of the world interpreting them in a fairly consistent and specific fashion for their purposes. . . or biases.Your screename, "Substantivalism"*3, harks back to the ancient roots of modern science in debates about the substance of reality. Greek Atomism was a good start toward a mechanistic worldview, except that it postulated no empty space for change, because nothingness was taboo. Yet, mechanism requires both hard stuff (substance) and soft space (relation) to produce a dynamic material & physical world that won't stand still for us to examine it. — Gnomon

Well, you could say this obscurity also pervades modern physics in general and the public is thrashed around as a rag doll in a storm of such poetic expressions which are neither clarified explicitly nor literalized properly to remove any confusion. Perhaps its not just obscure philosophy that needs to do some better PR but also modern physics as well.If that's what this thread is all about, you will find some sympathetic ears, but be prepared for accusations of preaching mystical "obsessions" and metaphysical woo-woo. — Gnomon

Everything that is declared modern physics is starting to be seen by me as preachy mystical "obsessions" as well. The only thing that survives being the math and its practical applications. All else would seem to be in need of clarification as to whether we formulate some transformation of these metaphorical statements into literal ones or become comfortable with metaphorical rhetoric. If its the former then this approach shouldn't have the same problems or failures of those that came before it. If its the latter then it becomes a question of what metaphors and their overlaps are to be considered scientific to begin with. -

Wayfarer

26.1kyou could say this obscurity also pervades modern physics in general and the public is thrashed around as a rag doll in a storm of such poetic expressions which are neither clarified explicitly nor literalized properly to remove any confusion. Perhaps its not just obscure philosophy that needs to do some better PR but also modern physics as well. — substantivalism

Wayfarer

26.1kyou could say this obscurity also pervades modern physics in general and the public is thrashed around as a rag doll in a storm of such poetic expressions which are neither clarified explicitly nor literalized properly to remove any confusion. Perhaps its not just obscure philosophy that needs to do some better PR but also modern physics as well. — substantivalism

That’s terrific writing. I’m really sensing the tension you are pointing out.

The only thing that survives being the math and its practical applications. — substantivalism

I would recommend looking into the origins of mathematical philosophy in Pythagoras. The Greeks had the insight that only number could be completely knowable; the expression A=A (the law of identity) offered an intrinsic certitude that things in the material/sensory world could only aspire to. If you can get hold of a copy of Bertrand Russell’s History of Western Philosophy, have a look at the chapter on Pythagoras. You might also enjoy an essay - originally a lecture - by Werner Heisenberg, The Debate between Plato and Democritus. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

As I was developing my personal philosophical worldview, I didn't intentionally seek to cast hard science into softer poetic forms. But Quantum Physics --- "the most mathematically accurate theory in the history of science" --- is also the most counter-intuitive and irrational. So, the use of metaphors & analogies seems to be mandatory. But such mushy terminology --- wave-particle is an actor playing two roles --- goes against the grain of classical mechanical physics. The simple cause-effect relationship is complicated by inserting a conscious mind into the event : cause-observation-effect (two slit experiments). Even the math of Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle includes confounding infinities. Consequently, I was left with no choice, but to follow the lead of the Copenhagen compromise between objectivity and subjectivity. Hence, to combine physics with metaphysics. :cool:. Perhaps, its more a research question as to whether there is some way to intuitively hold onto those poetic perennial forms of philosophy without succumbing to the same critiques from the 'shut up and calculate' crowd. — substantivalism

I assume the "entity" you refer to is something like an entangled wave-particle, which is neither here nor there, but everywhere. That's literally non-sense, but physicists eventually learned to "accept" such weirdness in exchange for uncanny technologies like quantum tunneling, that make your cell phone work wonders. I'm not familiar with Čapek, but Bergson and Whitehead were influential in the formation of my information-based worldview. :nerd:However, that did not stop the mechanistic theories of Classical physics of accepting such an entity, as that book by Milič Čapek supports, and that there are more concepts that such a view of the world accepted than is usually let on. — substantivalism

Former professional physicist, now video blogger, Sabine Hossenfelder agrees with that assessment in her critiques of What's Wrong With Modern Physics : "What can we learn from this? Well, one thing we learn is that if you rely on beauty you may get lucky. Sometimes it works." :smile:Perhaps its not just obscure philosophy that needs to do some better PR but also modern physics as well — substantivalism

HOSSENFELDER at 28 : did she rely on beauty?

-

javra

3.2kDo you think that modern physics, or even philosophy in general, has gone off the rails with regards to non-visualized poetry/metaphor and abstract obsessions? Or is there some way to lean into non-visualization through metaphor or mathematical modeling but without an occultist taste to it? Should we go back to a highly mechanistic picture of the world in scientific education/philosophy regardless of what those analogue models may specifically be? — substantivalism

javra

3.2kDo you think that modern physics, or even philosophy in general, has gone off the rails with regards to non-visualized poetry/metaphor and abstract obsessions? Or is there some way to lean into non-visualization through metaphor or mathematical modeling but without an occultist taste to it? Should we go back to a highly mechanistic picture of the world in scientific education/philosophy regardless of what those analogue models may specifically be? — substantivalism

It seems to me it's been written from a perspective of a kind of disillusionment, by someone who formerly believed that the role of science was to develop a true picture of the world, but has now come to see that this seems increasingly remote. — Wayfarer

You are not wrong in that assessment. In my life I have few interests and fewer things to be proud of in their stability as well as their personal meaningfulness. However, the deflationist and deconstructivist views of others upon all philosophy, but especially scientific thought, has resulted in a rather bitter view to it all. — substantivalism

In my own, maybe all too imperfect, intentions to be of help, I’ll express my own views regarding the many at times contradictory, and often non-intuitive, perspectives that have emerged from that one empirical science of modern physics.

Speaking for myself, I try not to mistake, or else equivocate, between a) the empirical sciences as enterprise and methodology and b) the conclusions, be they popularly upheld or not, which this same enterprise has resulted in and continues to produce.

I deem (a) to be grounded in the intent of an ever-improving, psychologically objective appraisal regarding that which is commonly actual to all and thereby empirically verifiable. For the science of physics, this then is the very nature of the physical world at large. Of emphasis here is the intent just mentioned and the use of the scientific method as an optimal means of bringing this same intent to fruition. Everything from falsifiable hypotheses, confounding-variable-devoid tests of such hypotheses (or as near to such tests as we can produce), replicability of these test’s results by anyone who so wants (and obviously has the means) to so test, and the very important peer-review method (which in its own way serves as a checks and balances of biases) by which the validity of all such aspects that the scientific method utilizes is optimally verified, hence optimally safeguarding against these same aspects being endowed with mistakes of some kind.

(A) might not be perfect, but we so far do not know of a better methodology for ascertaining that which is in fact actual relative to all agents irrespective of what agents might individually believe (this actuality to me being physical reality), this in optimally impartial manners.

In turn, I deem (b) to always be fallible in its nature, never in any respect presenting a definitively proven absolute truth. Yet, due to (a), (b) shall then tend toward what is in fact less partial, or biased, in comparison to beliefs held by individual agents. I’m more interested in neurology and related sciences so, using this as example, about half a century ago it was more or less generally upheld that an adult brain’s physiology was generally static, or hard-wired, for the individual’s life (that synaptic connections did not change in any way other than by either becoming stronger or weaker - for one example, the neuroscience professor in a lab I worked in as a tech after graduating college held onto this view quite stringently). Today, via the same implementation of the scientific method that led to this generally accepted belief, we’ve now generally come to accept that neural plasticity in the adult human brain remains an occurrent phenomena (for example, that new synaptic connections can at times be made or else can at times decay to such extent that they no longer are). The commonly accepted appraisal of what the data informs us of has changed—this due to newly acquired data that disproves the adequacy of former beliefs—but the science as methodology via which this data is acquired has nevertheless remained wholly unchanged.

As to the mathematical modeling (of the acquired empirical data) you mention, I generally place it within category (b). When it comes to the application of maths in category (a)—such is the case with statistics—issues become philosophical in nature, rather than scientific.

As just outlined, I then don’t view modern day sciences as being in any way undermined by views such as those you’ve mentioned. Science as category (a) remains wholly undefeated in relation to its purposes.

As to category (b) in respects to modern physics, I personally find it useful to remember that, because we don’t have a unified theory or everything physical, either the theory of relativity, quantum mechanics, or else both are then in some ways wrong—irrespective of their strong predictive value. This in parallel to how Newtonian physics is now known to be inaccurate—despite its predictive value yet being accurate enough for most purposes. When a theory of everything physical will be obtained, things will then click into place far better. Till then (if not even beyond), I find it best to not hold onto any so far well established physicist theory (ToR and QM included) as portraying an absolute truth—but as fallibilistic accounts which are known a priori to be in need of significant, maybe even foundational, tweaking. Nevertheless, the data so far acquired from modern physics will remain and need to be accounted for in whatever scientific developments regarding category (b) that might eventually result. Making the going "back to a highly mechanistic picture of the world in scientific education/philosophy" highly inappropriate.

I am hoping this might be of some help—even if it will not resolve all concerns (but, then again, such would be quite the utopia indeed :grin: ). -

Deleted User

0

Deleted User

0

I admit it's a trope of philosophical and scientific thought to think so highly of only the most abstract things we can entertain ourselves with. Galileo thought the world was written in that fashion if I recall and it's a further trope today to declare something as pseudo-science more so because it lacks mathematical basis rather than experimental one. However, something feels lacking and I fail to see how any attempt at explicating visually/metaphorically a casual "omph" could be seen as inferior to the black board.I would recommend looking into the origins of mathematical philosophy in Pythagoras. The Greeks had the insight that only number could be completely knowable; the expression A=A (the law of identity) offered an intrinsic certitude that things in the material/sensory world could only aspire to. If you can get hold of a copy of Bertrand Russell’s History of Western Philosophy, have a look at the chapter on Pythagoras. You might also enjoy an essay - originally a lecture - by Werner Heisenberg, The Debate between Plato and Democritus. — Wayfarer

That is one way to approach it which is to showcase the necessity of such language.As I was developing my personal philosophical worldview, I didn't intentionally seek to cast hard science into softer poetic forms. But Quantum Physics --- "the most mathematically accurate theory in the history of science" --- is also the most counter-intuitive and irrational. So, the use of metaphors & analogies seems to be mandatory. But such mushy terminology --- wave-particle is an actor playing two roles --- goes against the grain of classical mechanical physics. The simple cause-effect relationship is complicated by inserting a conscious mind into the event : cause-observation-effect (two slit experiments). Even the math of Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle includes confounding infinities. Consequently, I was left with no choice, but to follow the lead of the Copenhagen compromise between objectivity and subjectivity. Hence, to combine physics with metaphysics. :cool: — Gnomon

I was actually talking about the void or space as such an entity wasn't so alien but in fact was in a close alliance with Classical physics.I assume the "entity" you refer to is something like an entangled wave-particle, which is neither here nor there, but everywhere. That's literally non-sense, but physicists eventually learned to "accept" such weirdness in exchange for uncanny technologies like quantum tunneling, that make your cell phone work wonders. I'm not familiar with Čapek, but Bergson and Whitehead were influential in the formation of my information-based worldview. :nerd: — Gnomon

I do have Bergson and Whitehead on my list to read as they are prominent voices in giving new "organic" and "dynamic" language to talk about the world.

On the contrary we already do this modern return to mechanism except it's not called mechanism.Nevertheless, the data so far acquired from modern physics will remain and need to be accounted for in whatever scientific developments regarding category (b) that might eventually result. Making the going "back to a highly mechanistic picture of the world in scientific education/philosophy" highly inappropriate. — javra

It's called physical analogue modeling. While blindly juggling symbols and operational procedures may be common practice it leaves a sense of unintuitiveness of how to deal with some mathematical models.

This is a common thing to do in General Relativity as well as Quantum mechanics. They may use a mixture of combined physical phenomenon which are mathematically similar in certain respects/situations to wrap ones head around the derived mathematical relation we are referring to. Such as the case in this article which uses fluid and acoustic analogies to "investigate" black holes as well as hawking radiation.

However, the paper still uses talk or language about Einstein's field equations as to it being about "curved spacetime" which I see as a metaphorical line of speaking. The same in analogy to the mathematical/physical analogies they are creating.

The question then is whether a mathematical model without such physical analogies is really rather vacant and devoid of explanatory value. Is it possible to hold to a mathematical model as explanatory without either metaphorical or physical analogies as a part of it? Is it also possible/acceptable for one to construct a scientific explanation based only on analogue modeling and metaphorical speech?

As it seems that the impression I get from such articles is that these analogies are SLAVES to the mathematical model in question that they are meant to clarify. They do no work of their own and if needed physicists would be fine with purging such analogies from their being for a one inch long equation. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI admit it's a trope of philosophical and scientific thought to think so highly of only the most abstract things we can entertain ourselves with. — substantivalism

Wayfarer

26.1kI admit it's a trope of philosophical and scientific thought to think so highly of only the most abstract things we can entertain ourselves with. — substantivalism

It's not that quantification is either simply abstract or entertaining, but that it's exact. Insofar as you can quantify, you can predict and control. One of the prime factors in the success of science is the increasing scope and accuracy of measurement. In Plato there is recognition of the exact nature of arithmetical proofs, which are contrasted with value judgements about the sensory domain, hence dianoia, arithmetical reasoning, being judged higher that sense experience; when you know an arithmetic proof, you know it with perfect clarity and without reference to anything else. The Galileo quote you refer to was 'nature is written in mathematical language, and its characters are triangles, circles and other geometric figures, without which it is impossible to humanly understand a word; without these, one is wandering in a dark labyrinth.' Hence the fundamental significance of quantitative data in science, and the division I mentioned in the earlier post between primary (measurable) and secondary (subjective) attributes. -

javra

3.2kNevertheless, the data so far acquired from modern physics will remain and need to be accounted for in whatever scientific developments regarding category (b) that might eventually result. Making the going "back to a highly mechanistic picture of the world in scientific education/philosophy" highly inappropriate. — javra

javra

3.2kNevertheless, the data so far acquired from modern physics will remain and need to be accounted for in whatever scientific developments regarding category (b) that might eventually result. Making the going "back to a highly mechanistic picture of the world in scientific education/philosophy" highly inappropriate. — javra

On the contrary we already do this modern return to mechanism except it's not called mechanism.

It's called physical analogue modeling. [...] — substantivalism

Are you equating these models to what science in essence is? If you are, you then seem to disagree with my appraisals of what empirical science consists of. No biggie, but I am curious.

------

When I stated that the data remains, I was addressing the verifiable results which are for example obtained from the delayed-choice quantum erasure experiment—which pose serious problems either for classical notions of causation, for classical notions of physical identity, or else for both. And I so far understand both these classical notions to be requisite for any mechanistic account, even more so for any "highly mechanistic" account of the world in scientific philosophy.

The replicable data obtained from this experiment, then, will yet need to be accurately accounted for regardless of the implemented models, mathematical or otherwise; regardless of the philosophical explanations which inevitably make use of metaphysical assumptions regarding the nature of space, time, and causality; and so forth. As to the mathematics involved, it is directly related to the data—such that were the mathematical system implemented to be contradicted by empirical test, it would hold no scientific value. Here, for example, thinking of the classic tests which were accordant to Einstein's theory of general relativity; were these test to have not so been, the mathematical system/theory would not have held water. (Related to this, because string-theory is currently not falsifiable via tests, this mathematical system is argued by some to be non-scientific—even if other speculate that M-theory can be further developed into a unified theory of physics.) At any rate, while explanations and models for the acquired data can change, the data nevertheless remains.

-------

But going back to the issue of a highly mechanistic picture of the world:

To be clearer, by “mechanistic” I so far understand a model, system, process, thing, etc. that incorporates a classical billiard-ball-like understanding of causation and, thereby, entails the classical Newtonian understandings of space and time required for such causation’s mechanical occurrence. Do you have something else in mind in your use of the term?

If not, and if you know of any “highly mechanistic” model (regardless of its technical name; regardless of it being strictly mathematical or else in any way analogously representational) that can accurately account for results such as from the delayed-choice quantum erasure experiment, I’d be grateful for a reference to it. (The closest I can currently think of is the MWI of QM, but this fully deterministic understanding is not accordant to “mechanistic” as I’ve just described it.) -

Deleted User

0@Wayfarer @javra So I've now taken some time aside after finishing Metaphors We Live By from George Lakoff & Mark Johnson, The Philosophical Impact of Contemporary Physics by Milic Capek, and an article titled Naturalism, Quietism, and the Threat to Philosophy by Thomas J. Spiegel & Schwabe Verlag. I've also consulted some articles from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and also some articles from the pseudoscientific paper posting hotspot called viXra.org. If that looks familiar, yes, its just the rather more heavily relaxed and non-mainstream equivalent of arXiv.org. I've decided to jump on giving a summary of what I've learned so as to hopefully generate novel discussion or questioning. Though, I'm doubtful I will do all this exquisite work any profound justice. This will be long and for that I apologize.

Deleted User

0@Wayfarer @javra So I've now taken some time aside after finishing Metaphors We Live By from George Lakoff & Mark Johnson, The Philosophical Impact of Contemporary Physics by Milic Capek, and an article titled Naturalism, Quietism, and the Threat to Philosophy by Thomas J. Spiegel & Schwabe Verlag. I've also consulted some articles from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and also some articles from the pseudoscientific paper posting hotspot called viXra.org. If that looks familiar, yes, its just the rather more heavily relaxed and non-mainstream equivalent of arXiv.org. I've decided to jump on giving a summary of what I've learned so as to hopefully generate novel discussion or questioning. Though, I'm doubtful I will do all this exquisite work any profound justice. This will be long and for that I apologize.

Something that underlies all these articles from the non-Mainstream to these dissident philosophical perspectives is a clear feeling of disenfranchisement from the establishment. There is something that is lacking among these 'ivory towers' which misses the core point of why one philosophizes to begin with, how one constructs scientific explanations, what it means to be scientific, or what deserves to be called a 'fact'. The dramatic displays of scientific rigor and success in documentaries or interviews is seen as increasingly suspect. Something to be ripped a part from analyzing the ambiguities of the language used and show how their own layman speech betrays them intellectually speaking. Each of the works listed explicitly above attempt to synthesize a solution, as is always done, to the perennial conflict of old.

--------

In The Philosophical Impact of Contemporary Physics this message is front and center throughout the entirety of the work as Milic emphasizes the non-visual nature of how one can come to understand nature without the same perennial errors of those who came before. Such errors revolving around identity, the spatialized language with regards to time, the supremacy of the corpuscular-kinetic modeling of phenomena, the reign of determinism, certain properties of space, and an inherent splitting of nature into primary/secondary qualities.

A key point being the 'subconscious' element of Classical thinking which pervades all of modern physics despite their claims to the contrary. Even in antiquity, the attempts to circumvent perennial issues were rather devoid of rational teeth because the visual thinking they used had them imported in to begin with. An example of this is in the responses to the Eleatic problem of change and Zeno's arrow paradox. I.E. how can something change/move if its only ever composed stage wise of unchanging/un-moving instants? The mathematicians/theoretical physicist solution to this, in line with the Achilles tortoise paradox, ignores the perennial issue at its heart for a purely computational solution in terms of real analysis or limits. However, the usual solution to this from esoteric philosophies of old usually meant abandoning 'instants of time' for 'atomic intervals of time'. This, however, didn't deal directly with removing instants from our thinking as an 'interval' begs the question of a beginning and an end. Those edges being then instants in their own right even if only realized as limits. Further, this doesn't seem to have solved the perennial problem of change as we've rather substituted instantaneous moments for extended unchanging moments thereby still committing us to some peculiar view of nature in which change is. . . illusory or some purely mental phenomenon.

This is because the analogies that one visually conceives of when thinking of time itself, or space/causality/matter/motion, are fundamentally static in nature. Such as a block conception of time that views it pictorially as a collection of instantaneous NOW slices all stacked on top of each other similar to projector slides. That or put into analogy with a film strip whereby the change we perceive is, by the analogy itself, tricking us into thinking it's illusory as the real world doesn't yield true qualitative change but is unchanging fundamentally. I.E. its our consciousness that snakes up our worldline but not do to any 'internal' change of the worldline itself.

The Aristotelian notion of 'gunk' or matter that is not atomic but infinitely divisible is not deemed utterly irrational but rather stripped of much rationale to begin with as the change in size, weight, mass, momentum, energy, heat, or any other qualitative change is found in the unchanged. Heat is not some irreducible qualitative element of nature but a side-effect of the re-distribution/collisional interaction of the unchanging atomic constituents of reality. Any change in volume is by virtue of its 'parts' the result of them being moved farther apart or squished together and not some inherent qualitative change of the property of volume it possesses.

This idea of getting to the unchanged or fundamental then leads to a similar abstracted version of this which is the idea of looking for fundamental particles in nature. Even when Aether's were proposed by their originators to be 'fluidic' and a return to Aristotle's qualities in a sense they were then contradicted by those same physicists claiming this Aether actually had atomic parts. The only difference between this new Aether and the atomism before being the mere sheer number of atoms postulated. This thinking sinking deep into seeing phenomenon such as the Lorentzian contracted of electrons as not indicating qualitative change of fundamental elements but rather that our models indicate that the electron is itself not fundamental. There must be some more fundamental truly unchanging parts which explain how this electron gained or lost its volume! As the admittance of qualitative change in things would seem as if we've postulated the acceptance of 'something from nothing'. Whatever it is that atoms possess and what they are is unable to be changed including their shape or internal properties. In this sense, even if we attempted to undo the Classical biases of before by adopting a 'fluidic' Aether we'd still have to deal with the skepticism of others subconsciously that we have rejected the dictum ex nihilo, nihil fit.

Space is without boundary and fundamentally three-dimensional in nature. It being most importantly homogeneous, isotropic, casually inert, continuous, and Euclidean. There are esoteric philosophies which grabble with the Aristotelian idea of there being no space outside his spheres by using this pictorial imagery of throwing a spear or extending ones' arms beyond this outer most sphere. You can always imagine a more zoomed out view of an object of it sitting in a further, vaster, void and anything moving away from this thing still being 'in space'. The notion of a boundary of space, a hole, or a non-Euclidean nature being virtually ruled out fundamentally by such visual biases.

Further, space is itself not able to be influenced by physical things nor influence them as its core role is some vague logical differentiation of qualitatively similar atoms. It can be zoomed out as far as one pleases or zoomed in and similar to nesting dolls we can find universes within universes that themselves look eerily similar but just smaller. Ergo, the popular Rutherford analogy of an atom in complete similarity to our solar system. This is also dubbed the relativity of magnitude rather than mere continuity. Finally, space may serve the role of differentiating qualitatively similar atoms but its only matter itself that serves to distinguish a part of space from another and not space itself. Only the relative variation of atoms by separation and their motions serving to distinguish one place from another.

Another note is given about how this Classical line of thinking doesn't allow for one to leave the dichotomy of fatalistic determinism or random indeterminism. I.E. when one thinks of different frames of a universal 'movie' its either fully determined how it will all play out before you hit play or you could put in one frame after another with each being fundamentally disjoint/disconnected. The only reason then that this momentary blinking present has any sense of continuity or coherency being some great miracle of nature.

How does one circumvent this all? What interpretation should one then give special/general relativity which isn't one characteristic of a 'block' spacetime? What the true interpretation of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle?

Well, its to subvert everything brought about in the entire corpuscular-kinetic picture of the world including the usage of pictorial language. While the Classical picture separated out space from matter the lesson to be learned from General Relativity is one in which the two are rather actually conjoined. This means it becomes rather vague and uncertain fundamentally where space ends or matter begins. It also means to regard space as not homogeneous in the sense that its non-Euclidean of a certain sort. To regard it as discontinuous on some fundamental level similar to theories of quantum gravity which atomize space BUT without the problematic visual biases here so perhaps particles could in some sense be 'gaps' in space. Given matter is seen as another side of the coin of spacetime then this means it's not casually inert anymore but rather actively plays its own role.

The biggest change being to institute, via inspiring work from Bergson or Whitehead, a fundamental notion of change/time that is in no way reducible to the unchanging. Its an acknowledgement of the irrationality of such a pursuit and an admittance of what needs to be done. Here is where a clarification is in order as to how one should interpret Special Relativity and its relativity of simultaneity. Contrary to wide-spread belief there is actually nothing really shocking about what SR has to bring to the table as what becomes relativized in the theory. These being temporal measurements we ascribe intervals of time and casually un-related events. Events which are casually related cannot be made to happen in a different causal order by frame changes. They are in fact topologically invariant and so while it might be relative how long we ascribe metrical units. . . the 'flow of time' is in fact not so relative. The 'movement' from the 'future' to the 'past' is left untouched.

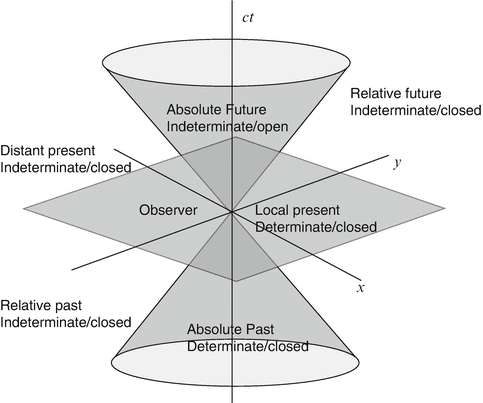

Our notion of an instantaneous NOW is left in shambles without instantaneous actions at a distance and with that our notion of NOW is inexorably intertwined with HERE. I.E. there is now only the HERE-NOW and the THERE-THEN where the notion of THERE-NOW is left in an undetermined or vague sense. Asking such a question as what its like THERE-NOW being as nonsense as saying we are interacting with them right here when in fact we are not.

Despite the claims to the contrary that one either accept a spatialized block interpretation of SR or some highly solipsistic presentist strawman we should admit to the best of both worlds. That the future is left indeterminate or in Aristotle's words filled with potentiality which awaits actualization in the present to then be shrugged off into the determinate past. A concept of time that is 'thick' and begets true 'novelty' in nature as the indeterminate future filled with potentialities talks to the present as the present does to the past in a strongly casual manner but one which allows for true variation in the world. One which cements the irreducibility of the arrow of time and scoffs at the idea of eternal recurrence.

A cohesive and beautiful orchestra of distinct voices which form a coherent whole yet remain distinct. Notes which lose their reality if you analyze them in too short an interval of time and whose reality isn't really so unless you hear their full beat. This usage of musical metaphor being what Milic and those he credits with process philosophizing use rather than pictorial or spatialized ones in getting at these esoteric notions of reality.

There is another characteristic of the approach here which is to regard quantitative ascriptions as something required by our need to manipulate nature but ill-equipped to deal with nature on its own terms. We yearn for boundaries, clear separations, static states, patterns, continuity, etc. However, it seems that nature begets both this quantitative view and the visual analogies we use which force such concepts on us to begin with. Our quantitative manipulations may be useful but their universality is itself the illusion.

What language do we use then? How can we un-visualize our language for the purposes of physics which doesn't fall into mere mathematical symbolism?

--------

I would feel then that in line with Milic the only direction to go would be to one of a highly metaphorical or esoteric sense of philosophizing which also acknowledges the fallibility of such an approach or its limitations. That way we, as Milic feared, neither fall into some esoteric animisim of old or be accused of seeing math in nature (panmatheism)It's not that quantification is either simply abstract or entertaining, but that it's exact. Insofar as you can quantify, you can predict and control. One of the prime factors in the success of science is the increasing scope and accuracy of measurement. In Plato there is recognition of the exact nature of arithmetical proofs, which are contrasted with value judgements about the sensory domain, hence dianoia, arithmetical reasoning, being judged higher that sense experience; when you know an arithmetic proof, you know it with perfect clarity and without reference to anything else. The Galileo quote you refer to was 'nature is written in mathematical language, and its characters are triangles, circles and other geometric figures, without which it is impossible to humanly understand a word; without these, one is wandering in a dark labyrinth.' Hence the fundamental significance of quantitative data in science, and the division I mentioned in the earlier post between primary (measurable) and secondary (subjective) attributes. — Wayfarer

--------

More playing devils advocate here. Course, its not too far from the Stanford Encyclopedia article's on science to think that true scientific explanation is to be found in visual analogical modeling. Especially given most of scientific theorizing is merely mathematical modeling, visual analogical modeling, and metaphorical prose. Its just a question of intuitive primacy as to which of these aspects should be emphasized more and what we think an explanation amounts to philosophically speaking.Are you equating these models to what science in essence is? If you are, you then seem to disagree with my appraisals of what empirical science consists of. No biggie, but I am curious. — javra

Math for example makes for a rather good description of nature. . . but an explanation?

So did GR. . . and Quantum mechanics. . . or any physics which has come before. Experiments do not decide interpretations in any determinate sense but rather can remain stubborn biases without proof or dis-proof or in lieu of apparent dis-proof. Take the idea of talk about fundamental particles or constituents of reality which is a stubborn assumption of a Classical mentality. No amount of scientific argument or experimentation could settle the rationality of such a doctrine as either the particle is split showcasing its not fundamental, its postulated it is fundamental if it meets certain requirements, or if those requirements aren't met then its assumed to be not fundamental. ITS NOT TESTABLE!When I stated that the data remains, I was addressing the verifiable results which are for example obtained from the delayed-choice quantum erasure experiment—which pose serious problems either for classical notions of causation, for classical notions of physical identity, or else for both. And I so far understand both these classical notions to be requisite for any mechanistic account, even more so for any "highly mechanistic" account of the world in scientific philosophy. — javra

Again, taking the example of the Lorentzian contraction of an electron. This doesn't have to imply a disproof of the corpuscular model but rather a proof of its non-fundamentality model-wise.

You don't falsify the corpuscular-kinetic biases of old and also don't falsify the conception of energy conservation. You don't falsify Classical mechanics or prove an indeterminate reality from Heisenberg's uncertainty principle. Its only on higher order philosophical intuitions that this is done.

Exactly, the epicycles of the day and the things they model remain unchanged as they are correct by coincidence but if shown wrong then the math is MODIFIED to account for this. You may claim its not done so in the sense of curve fitting but its fitting nonetheless and this may be curve fitting which takes into account more than the data itself. Its still just theory fitting.The replicable data obtained from this experiment, then, will yet need to be accurately accounted for regardless of the implemented models, mathematical or otherwise; regardless of the philosophical explanations which inevitably make use of metaphysical assumptions regarding the nature of space, time, and causality; and so forth. As to the mathematics involved, it is directly related to the data—such that were the mathematical system implemented to be contradicted by empirical test, it would hold no scientific value. Here, for example, thinking of the classic tests which were accordant to Einstein's theory of general relativity; were these test to have not so been, the mathematical system/theory would not have held water. (Related to this, because string-theory is currently not falsifiable via tests, this mathematical system is argued by some to be non-scientific—even if other speculate that M-theory can be further developed into a unified theory of physics.) At any rate, while explanations and models for the acquired data can change, the data nevertheless remains. — javra

Math is ambivalent to interpretation and can beget ANY interpretation.

For example, does General relativity make gravity not a force? According to Einstein's field equations it does not but according to a mathematically equivalent version which predict all the same things, teleparallel gravity, its more akin to a force or a change of torsion rather than curvature. This is similar to how Newtonian gravitation can be geometrized into what is called Newton-Cartan gravity which removes the force from gravity to make it a part of the curvature of space mathematically speaking. -

Deleted User

0@javra You can only go so far with the, ". . . but the experiments showcase its not rational to assume. . ."

Deleted User

0@javra You can only go so far with the, ". . . but the experiments showcase its not rational to assume. . ."

As given enough time someone could construct a model from Classical or other such biases to make it consistent with both the math and experimental results.

You either have to meet them on a metaphysical/philosophical level or just commit in heart as well as to the spirit of the dictum:

Shut up and calculate!

For example, you could browse that link to viXra.org . It may be uncommon but corpuscular modeling is not dead among the non-mainstream nor is its mathematical maturity lacking. -

Deleted User

0

Deleted User

0

Something more inline with what Milic calls the corpuscular-kinetic view of nature which arises almost entirely in certain respects from our imaginative capacities for visualization. Something tinged by spatialized analogies.To be clearer, by “mechanistic” I so far understand a model, system, process, thing, etc. that incorporates a classical billiard-ball-like understanding of causation and, thereby, entails the classical Newtonian understandings of space and time required for such causation’s mechanical occurrence. Do you have something else in mind in your use of the term? — javra

This includes both the block spacetime usually attributed to Minkowski, the absolute space of Newton, or the relational instantaneous spaces of Leibniz/Huygens/etc. These are all analogies infected by Classical visualization biases and the metaphorical analogies they yield. -

javra

3.2kAre you equating these models to what science in essence is? If you are, you then seem to disagree with my appraisals of what empirical science consists of. No biggie, but I am curious. — javra

javra

3.2kAre you equating these models to what science in essence is? If you are, you then seem to disagree with my appraisals of what empirical science consists of. No biggie, but I am curious. — javra

More playing devils advocate here. Course, its not too far from the Stanford Encyclopedia article's on science to think that true scientific explanation is to be found in visual analogical modeling. — substantivalism

Just saw these posts. Just in case you'll revisit the website ...

Instead of inadvertently getting bogged down with the details of interpretation, I'll try to simplify my pov in the following way: For there to be modeling, or else interpretation, in the first place, there first needs (as in necessity) to be empirical data to be modeled, else interpreted. Yes, science engages in modeling via which interpretation of data occurs. But what I'm attempting to express first and foremost is that the empirical sciences proper, via its use of the scientific method, collects empirical data in as an objective manner as currently fathomable to us humans. Models and interpretations that do not account for all data thereby accumulated - or worse, that logically contradict this data in total or in part - will be deemed falsified. As a crude example easy to gain accord upon, the theory that Earth is geometrically flat is one such model via which our communal empirical data can become interpreted. Or, more exotic, so too is the theory that planet Earth is hollow and inhabited by sapient beings in its core (which I have heard people address). These models are wrong, i.e. incorrect, only because they fail to account for all commonly shared or else commonly accessible empirical data and on occasion directly contradict it.

The empirical sciences as means of (relatively) objective data acquisition has almost nothing whatsoever to do with mathematics - especially when addressing mathematical modeling. And the latter would be nonexistent in complete absence of the former - at the very least epistemologically.

Science (by which I here mean the scientific-method-utilizing empirical sciences) does not, and cannot, fail as our optimal means of obtaining unbiased empirical knowledge regarding what perceptually is.

It is the second aspect of science - that of finding optimal explanations for this same data just addressed (what in philosophy is termed "explanatory power") - that you seem to me to be by in large addressing. Modeling of data assumes some interpretation of said data, and thereby already entails at least some rudimentary explanation even before these models are applied for the sake of obtaining even more empirical data. But again, when the models fail to account for all data obtained, or else contradict the data, the models are then known to be wrong ... our human predilection to hold onto those explanations that are familiar and ingrained in us notwithstanding. (The flat-Earther, just as much as any Young Earth Creationist, will discern the contradictions with data but will yet maintain their model of the world at all costs, often resulting in fabulated truths that attempt to reshape the data so as to fit the held onto model. But, again, it is precisely because this occurs that these two modelings of the world are considered non-scientific.) Otherwise, two or more disparate models that account for the same data without willfully neglecting some of the data or else contradicting it will then all be in play as viable possibilities as to what might in fact be the case.

Is there any major disagreement in what I've so far expressed as pertains to science?

(p.s., in case I don't hear back from you relatively soon, it might be a while till I again reply) -

Deleted User

0

Deleted User

0