-

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kRight, but it's worth pointing out that this is sometimes denied (i.e., there is no truth about "what a thing is") and people still try to do ontology with this assumption. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kRight, but it's worth pointing out that this is sometimes denied (i.e., there is no truth about "what a thing is") and people still try to do ontology with this assumption. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I agree, and I believe that this as well, is a worthwhile ontology. I was just responding to Banno's implication, that an ontology which held that there is truth and falsity to what a thing is, is not a worthwhile ontology.

IMO, this mostly comes down to the elevation of potency over actuality. When the order is inverted, then one always has limitless possibility first, and only after any (arbitrary) definiteness. Voluntarism plays a large role here. It becomes the will (of the individual, God, the collective language community, or a sort of "world will") that makes anything what it is through an initial act of naming/stipulation. But prior to that act, there is only potency without form and will. — Count Timothy von Icarus

The problem I have with this sort of ontology, the sort that assigns priority to potency, is that the patterns and regularities become chance occurrences. Then there is no way out of this highly improbable, chance occurrence ontology, so God becomes the only alternative. But if we do not proceed in that way, we can focus directly on the potency/actuality relation.

Presumably though, you need knowledge of an object in order to have any volitions towards that object. This is why I think knowing (even if it is just sense knowledge) must be prior to willing, and so acquisition of forms prior to "rules of language," and of course, act before potency (since potency never moves to act by itself, unless it does so for no reason at all, randomly). — Count Timothy von Icarus

I agree with this.

Edit: I suppose another fault line here that ties into your post (which I agree with) is: "truth as a property of being" versus "truth solely as a property of sentences." In the latter, nothing is true until a language has been created, and so nothing can truly be anything until a linguistic context exists. That might still require form to explain though, because again, it seems some knowledge must lie prior to naming. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I look at "truth as the property of sentences" as naivety. All sentences must be judged for meaning, prior to being judged for truth, and it is the meaning which is judged for truth. Truth and falsity are judgements bout meaning, This implies that the judgement of truth is dependent on the interpretation. Now we have an issue of subjective vs. objective interpretation, and the possibility of objective truth tends to get lost. -

Banno

30.6kIt's not that all predication is equivocation, but that ordinary language is flexible and dependent on context. This is not a threat to logic, which can happily rely on univocal terms. Our understanding of words is shaped by practical use, not metaphysical essences. In this view, terms like "round" or "red" don't require metaphysical forms to function meaningfully in context, nor does logic.

Banno

30.6kIt's not that all predication is equivocation, but that ordinary language is flexible and dependent on context. This is not a threat to logic, which can happily rely on univocal terms. Our understanding of words is shaped by practical use, not metaphysical essences. In this view, terms like "round" or "red" don't require metaphysical forms to function meaningfully in context, nor does logic. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

It's not that all predication is equivocation, but that ordinary language is flexible and dependent on context.

Right, but if one does not distinguish between univocal and equivocal usage then common facts such as "running involves legs," become unequivocally false because refrigerators, rivers, roads, and noses all "run." Ordinary language involves equivocal, analogical, and univocal predication. Form, the actuality of things, relates to the latter two.

This is not a threat to logic, which can happily rely on univocal terms.

Maybe not to formal logic, but the primary use of logic, including in the natural sciences, uses natural language. So, it would be problematic if equivocity rendered something like natural language syllogisms invariably subject to vagueness.

But would this leave formal logic in a good place? Any term used in formal logic, say M for "man," couldn't correspond univocally to any natural language usage of "man" if all terms were subject to the same vagueness as "game." Formal logic and natural language would be talking about different things.

Our understanding of words is shaped by practical use, not metaphysical essences. In this view, terms like "round" or "red" don't require metaphysical forms to function meaningfully in context, nor does logic.

And what determines practical use? Here is the argument, existence is prior to speech. There are round things, ants, trees, etc. prior to speech, and prior to the existence of any "language community." For example, the Earth is spherical and it was spherical prior to man deciding what the token 'spherical' should mean. It was true that the Earth was spherical prior to any man declaring it as such.

Unless "practical use" is determined by nothing at all, or by nothing but the sheer human will, as uninformed by the world around it, then it will be informed by the being of things (through the senses). A term like "round" is "practically useful" precisely because round things exist prior to the creation of the term (or of language itself). Children who have not learned the word "round" presumably still experience round things (and indeed they are capable of of sorting shapes prior to learning their names). Experience is prior to naming. But the form is called in to explain how things are round, ants, trees, etc., not primarily to explain how words work.

Nor does realism suppose any sort of metaphysical super glue between tokens and forms in the way you present it. Indeed, Plato has Socrates spend a lot of time exploring how people mean quite different things by using the same token. If Plato held the naive view you attribute to him, then the opening books of the Republic, where "justice" is being defined and used in radically different ways, shouldn't exist. -

Gnomon

4.4kWhy should there be a thing that is common to all our uses of a word? — Banno

Gnomon

4.4kWhy should there be a thing that is common to all our uses of a word? — Banno

As pointed out, there is no universal or general or essential THING to which our words point. What is "common" to words is meaning, not matter. And meaning is mental, not physical ; it's abstract, not concrete. So your "why?"question only makes sense from a materialist perspective, in which ideas, thoughts, feelings, etc are made of material atoms, similar to those that compose physical objects. Please pardon the "Materialism label", you may have a somewhat different meaning in mind for your "Thing".

Universal refers to a whole integrated system, not its parts. Generalization is a mental act that goes beyond empirical evidence to imagine all Things that have some common essence. The Essence of a Thing is not another thing, but the defining Quality of the thing. The atom of Qualia is a subjective, experiential, conceptual relationship between things & observers, and their meaning in a broad context. The "problem of Universals" is that they are not real things*1.

Empirical Science does not evaluate Qualia (meanings ; forms) , it counts Quanta (things). It's the job of Philosophy to seek-out the Forms that are common to all uses of our words, and then to describe the specific Meaning that applies to the topic under discussion. The philosophical quest is not for the particular Thing, but for the essential ding an sich.

But, you probably know all of this, and just need to be reminded, that this is a philosophy forum, where we do not dissect Things, but Ideas. Why should such non-specific Universals exist? Because we humans aspire to a god-like top-down view of the world. And we have the mental power to imagine*2 things that do not exist in the physical world, but subsist in the metaphysical ream of ideas & qualia. :smile:

*1. Universal Concepts :

In philosophy, universals are abstract qualities or characteristics that are shared by multiple objects or things, existing independently of specific instances. They are often seen as the fundamental building blocks of knowledge, explaining why things are similar and allowing us to categorize them. The "problem of universals" delves into the nature and existence of these shared characteristics, asking whether they are real entities, mind-dependent concepts, or simply names for similar things.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=philosophy+universals

*2. It wasn't Elon Musk who imagined an American-made electric car for ordinary people, but a couple of visionary entrepreneurs. They eventually realized an ideal concept.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=origin+of+tesla+electric+car -

Manuel

4.4kUp to interpretation, but as I take it, it's an attempt to make sense of concepts which we experience in individualized actualizations: we see a horse, or horses, flowers, a book, etc.

Manuel

4.4kUp to interpretation, but as I take it, it's an attempt to make sense of concepts which we experience in individualized actualizations: we see a horse, or horses, flowers, a book, etc.

But how can we recognize these things as such without having an idea of them, more perfect than what we encounter in real life (which are defective: the book may be worn out, the horse may look a bit ugly, etc.)?

You postulate an idea to explain how many things can be one, in a sense.

This may not be scholarly interpretation, but certainly appealing, if not correct as originally stated. Its influence has been astonishing. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Principles might be a better way to understand it.

The epistemic issues raised by multiplicity and ceaseless change are addressed by Aristotle’s distinction betweenprinciples and causes. Aristotle presents this distinction early in the Physics through a criticism of Anaxagoras.1 Anaxagoras posits an infinite number of principles at work in the world. Were Anaxagoras correct, discursive knowledge would be impossible. For instance, if we wanted to know “how bows work,” we would have to come to know each individual instance of a bow shooting an arrow, since there would be no unifying principle through which all bows work. Yet we cannot come to know an infinite multitude in a finite time.2

However, an infinite (or practically infinite) number of causes does not preclude meaningful knowledge if we allow that many causes might be known through a single principle (a One), which manifests at many times and in many places (the Many). Further, such principles do seem to be knowable. For instance, the principle of lift allows us to explain many instances of flight, both as respects animals and flying machines. Moreover, a single unifying principle might be relevant to many distinct sciences, just as the principle of lift informs both our understanding of flying organisms (biology) and flying machines (engineering).

For Aristotle, what are “better known to us” are the concrete particulars experienced directly by the senses. By contrast, what are “better known in themselves” are the more general principles at work in the world.3,i Since every effect is a sign of its causes, we can move from the unmanageable multiplicity of concrete particulars to a deeper understanding of the world.ii

For instance, individual insects are what are best known to us. In most parts of the world, we can directly experience vast multitudes of them simply by stepping outside our homes. However, there are 200 million insects for each human on the planet, and perhaps 30 million insect species.4 If knowledge could only be acquired through the experience of particulars, it seems that we could only ever come to know an infinitesimally small amount of what there is to know about insects. However, the entomologist is able to understand much about insects because they understand the principles that are unequally realized in individual species and particular members of those species.iii

Plato's Theory of Forms is a particular metaphysical explanation of unifying principles. Whether it was even originally intended as the sort of naive "two world's Platonism" that is often associated with Plato today is an open question (I for one am doubtful). But either way, Aristotle and then the Neo-Platonists make some useful elucidations of the theory (how much they are really altering it is also an open question).

Plato didn't think there was a form for every generalizable term. This is why examples using artifacts are not good counterexamples for pointing out problems with the Theory of Forms. One of the points of the theory is to be able to distinguish between substance and accidents/relation, but in artifact examples these become easily confused. Hence, books might not be a great example. Plato's student Aristotle rejects the idea that Homer's Iliad would have a definition and also casts doubt on even simple artifacts having essences, and I think he is in line with his old master here. If there has to be a form for every term, and there are potentially infinite, relatively arbitrary terms, then the forms would be useless for doing what they are called in to do.

Plato rejects materialist attempts to explain everything on the basis of that of which it was made. According to Plato, the entities that best merit the title “beings” are the intelligible Forms, which material objects imperfectly copy. These Forms are not substances in the sense of being either ordinary objects as opposed to properties or the subjects of change. Rather they are the driving principles that give structure and purpose to everything else. At Sophist (255c), Plato also draws a distinction between things that exist “in themselves” and things that exist “in relation to something else”. Though its precise nature is subject to interpretation, this distinction can be seen as a precursor to Aristotle’s distinction between substances and non-substances described in the next section, and later followers of Aristotle often adopt Plato’s terminology.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/substance/

-

Wayfarer

26.2k

Wayfarer

26.2k

Plato rejects materialist attempts to explain everything on the basis of that of which it was made. According to Plato, the entities that best merit the title “beings” are the intelligible Forms, which material objects imperfectly copy. — SEP. Substance

This definition seems to blur two quite different senses of the term being. In contemporary English, "beings" typically refers to individual entities—what we might call things or particulars—especially living or sentient beings. But in the context of Plato’s metaphysics, "being" refers not to discrete entities, but to what most truly is—that which grounds the very reality and intelligibility of particulars.

The Forms, in Plato’s view, are not "beings" in the same sense as horses or trees. They are not rival “things” set over against the sensible world. Rather, they are what makes the sensible world intelligible and real at all. As Eric Perl puts it:

Plato’s understanding of reality as form, then, is not at all a matter of setting up intelligible forms in opposition to sensible things, as if forms rather than sensible things are what is real. On the contrary, forms are the very guarantee of sensible things: in order that sensible things may have any identity, any truth, any reality, they must have and display intelligible ‘looks,’ or forms, in virtue of which they are what they are and so are anything at all. It is in precisely this sense that forms are the reality of all things. Far from stripping the sensible world of all intelligibility and locating it ‘elsewhere,’ Plato expressly presents the forms as the truth, the whatness, the intelligibility, and hence the reality, of the world. — Eric Perl - Thinking Being p25

Think about this way - take any object. The very first thing you need to do, is identify it. 'Hey, it's an 'X'. If you can't identify it, then you don't know what it is.

I notice in the opening of the SEP article Substance, the description of Brahman as “some fundamental kind of entity” seeks to impose a thing-like characterization on a concept that, in its original context, is expressly beyond all such determinations - which is precisely what the term 'reification' means.

An entity, after all, is typically understood as a bounded, identifiable thing. But Brahman, like Plato’s Being or Heidegger’s Sein, is not an entity among other entities. It is that which makes beings possible, while itself transcending all objectification. The tendency to treat foundational metaphysical principles as “things” or “entities” characterises what Heidegger criticized as 'ontotheology'. -

Banno

30.6kBeing univocal is something we do, not something found in a name. That the p in <p^(p⊃q)⊢q> is univocal is no more than how we are treat the p. One could also treat the two "p"'s as quite different, in which case the MP may not follow.

Banno

30.6kBeing univocal is something we do, not something found in a name. That the p in <p^(p⊃q)⊢q> is univocal is no more than how we are treat the p. One could also treat the two "p"'s as quite different, in which case the MP may not follow.

The use of a word is the simplest example of our differentiating amongst the things in the world. Someone who does not know the word "round" perhaps differentiates marbles from blocks, and in doing so shows their understanding. Again, look to what they are doing, to use, to see if they understand the concept, and show your understanding by acting in ways that are dependent on that understanding. Language is just an easy to use sub-class of the things we do.

I'd prefer to say that practical use is determined by intent rather than will.

Still no need to invoke forms.

If you are saying that meaning is seen in what we do, then we agree. There's no need to invoke forms to explain what we do. We can just act. -

Banno

30.6kSo what. Fill out your argument.

Banno

30.6kSo what. Fill out your argument.

At issue is how predicates and universals and forms and so on are related and what they amount to. Calling predicates "universals" or "forms" doesn't do much of anything.

But also, doing is not explaining.

So fill out your argument. -

frank

19k

frank

19k

1: You said there's no need to invoke forms to explain what we do.

2: Forms and universals are the same thing

3: You asserted that there's no need to invoke universals to explain what we do

4. In fact, you can't explain anything at all without using universals. You certainly can't explain what we do without using them.

What I did there was highlight your use of "explain" to lead into reflections on how we're all bound to universals because we can't think or speak without using them. So I was criticizing your attempt to frame priorities in terms of actions.

Yes, we certainly do things. This was never in question. But without conscious thoughts about actions, there would be nothing. Nothing acknowledged. Nothing remembered. Nothing asked. Nothing answered. And definitely nothing explained. Because you can't think without universals. They are on the table and you can't sweep them off.

There is a pathway from here to Gnosticism. Let me know if I need to flesh that out. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9k

Nevertheless, Aristotle went on to demonstrate how forms are necessary to support the law of identity, and the idea that there is what a thing is. This was a modified theory of Forms, required after Plato obliterated the old one. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9k

It's just a matter of having an adequate understanding. Something the vast majority will never take the time to develop. Look at how many dialogues Plato wrote before he got to the Parmenides. It's not something that comes easy. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kOMG, interpretations could go on forever. But you're right, it would be awesome because it's incredibly difficult. Maybe later.

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kOMG, interpretations could go on forever. But you're right, it would be awesome because it's incredibly difficult. Maybe later. -

Manuel

4.4k

Manuel

4.4k

That's a much better way of understanding the issue and I think your explanation is quite sensible. Of course, it becomes very tricky to argue that certain artifacts (or all of them) should not be thought of in terms of forms or ideas, because one can easily reply, "Ok, no books, but why a horse and not a donkey?"

It's true that the problem then becomes, well if everything has to have a form we will have infinite forms. Then we'd have to say something like certain ideas are the basis for other ideas. And we'd want to have a fixed number of ideas.

So, principles do make more sense, albeit still problematic. -

Apustimelogist

946Anyhow, how does one figure out how to "apply a rule for the word round," if there are not first round things? The form is, first and foremost, called in to explain the existence of round things, second our perceptions of them, and then language. It is not primarily about language because language was never considered "first philosophy" before the advent of analytic philosophy (i.e., "being and thought are prior to speaking.") People must be able to identify roundness to use to words to refer to — Count Timothy von Icarus

Apustimelogist

946Anyhow, how does one figure out how to "apply a rule for the word round," if there are not first round things? The form is, first and foremost, called in to explain the existence of round things, second our perceptions of them, and then language. It is not primarily about language because language was never considered "first philosophy" before the advent of analytic philosophy (i.e., "being and thought are prior to speaking.") People must be able to identify roundness to use to words to refer to — Count Timothy von Icarus

But anyone using the word 'round' is using it because they are engaging with the world around them and they see 'round' things.

Imo, if we want to explain the actual reasons why we use the word 'round', you have to talk about an immensely complicated brain and how it interacts with the rest of a very complicated world in an intractable manner - from the perspective of our own intelligibility - to infer something about how it represents or embodies structure out in the world.

We can't actually do that, and for any intelligible investigation of that we must presuppose our own concepts to know what we are looking for.

So when someone says that you need 'roundness' to explain why we use the word 'round'. What are you actually saying? Because none of us actually know how or why we personally are able to perceive and point out 'roundness' in the world, all you have really done is re-assert your own word use. You haven't actually explained anything and so your perspective ends up being vacuously the same as the word-use one which additionally wants us to say stuff like 'oranges are round iff oranges are round' which is asserting that 'roundness' is the case in conjunction with what is seen in the world - which we can point at, also communicating what we are pointing at to other people who use the word in the same way.

So by invoking forms have you meaningfully added anything? Not really - nothing that has not already been asserted by someone capable of using sentences like 'oranges are round iff oranges are round'. I can asser that round things exist without dressing it up in "forms" or "universals". Fine, we can call it that if you want, but I don't know if there is anything more interesting to say about that which wouldn't end up on someone falling back on and taking for granted their own exceptional abilities to make distinctions in the world and use words without really knowing how they do it.

And my own views - about what we might see as 'real' in the world or engagement with a world that 'real-ly' exists independent of us - fully acknowledges this, because the most generic way I think we can talk about the world is in terms of structure...

But what does that word actually mean? Because it is so generic, its very difficult to describe and elaborate on what that word actually means. Nonetheless, I have learned to use this word effectively in virtue of a brain that can make abstract inferences and predictions about my sensory world, and can use the word intelligibly to tell a story about the world which I think has less caveats than certain other stories. But in telling this story, I am still somewhat taking for granted the fact that I don't really know the specific details of how I am doing this. No matter how hard I try, I cannot elevate the kind of metaphysical meat of my word-use of 'structure' here into something which is actually explanatorily useful beyond being a kind of component of my story that relates to other parts of the story.

Neither can I elevate various other concepts like, say, "red" or "being", "same" or perhaps even something like "plus"... I am sure, many others. To me, simply re-asserting these latter examples as if there is something else additional to say isn't interesting (even if these are all useful words about stuff), especially when clearly what makes the world tick is to be found in our physical theories that predict what we see - and in theory, an understanding of brains that might give us some understanding into how we see those what we see, and make use of what we see in intelligent ways. Again, the useful way of talking about our theories of the world, with the least caveats, may be in terms of structure and brains' inferences about structure - useful words for my story without needing to elaborate those words in some additional, excessive way. Is there actually much difference between my 'structure' and your 'forms' (in the most generic sense of structure)? Maybe I just prefer the former word without the connotations of the latter... other similar words might be 'patterns', 'regularities', etc, etc.

There is necessarily a strange loop here of sorts in the sense that: understanding and using theories is also something we do. But I do not need to redundantly inflate ontologies that are explantorily useful beyond just how my brain works, resulting in word use. Sure, I will say there are 'round' things, but there are things much more interesting that make 'round' things and everything else tick. Again, even with "what makes the world tick" has limits in the sense that I cannot give you an interesting elaboration on what structure means. I don't need to arbitrarily and redundantly lay out a list of all the of these "forms" that "exist" and try to elevate them in some way, even though I don't really have anything interesting to say about them other than I see stuff with these properties. And because that is all I can say, I am effectively just re-asserting my own word use which renders any attempt to point out something salient about "forms" vacuous and effectively no different than re-asserting the notion that word-use is what is fundamental about concepts.

So I guess my conclusion is that appealing to forms and word-use is not meaningfully different. They are only different when trying to inflate stuff unnecessarily, which cannot be done in an interesting, intelligible way imo. The explanatory importance of concepts is how they relate to other concepts, and I think a theory of "forms" would place some overly abstract concepts or "universals" in a central role amongst our ontological concepts about the world where they have no business being. At the core and center is our best scientific theories, not the patterns that "supervene" at a higher level of description. "Roundness" exists, but lets not make it out to be something more important than it really is. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

But anyone using the word 'round' is using it because they are engaging with the world around them and they see 'round' things.

Indeed, that was precisely my point.

Imo, if we want to explain the actual reasons why we use the word round, you have to talk about an immensely complicated brain and how it interacts with the rest of a very complicated world in an intractable manner - from the perspective of our own intelligibility - to infer something about how it represents or embodies structure out in the world in the world.

I don't think neuroscience is any more properly first philosophy then philosophy of language, particularly if it leads to the radical skepticism you lay out in the rest of the post (a skepticism at odds with plenty of neuroscience itself).

For instance, the claim that "none of us actually know how or why we personally are able to perceive and point out 'roundness' in the world," is simply not one many people, including scientists, are going to agree with. There are great mysteries related to consciousness, but how (and that) things possess shape and how their shape in communicated through intervening media to a person, and how the sense organs engage this information, is well understood in some respects. At any rate, doubts that "anything is really round" involve a quite expansive skepticism.

However, even if we grant this skepticism, it wouldn't follow that the very diverse, well-developed tradition of metaphysical theories endorsing a notion of form would be rendered contentless. I'm not following this jump at all. This would be like saying that, because different interpretations of quantum mechanics are not currently decisively testable against one another, they fail to say anything unique about the world at all. A metaphysics of form might be wrong (although skepticism precludes even saying this much), or it might be unjustified, but it isn't "not saying anything," or a theory about word use.

So I guess my conclusion is that appealing to forms and word-use is not meaningfully different.

One might indeed criticize a metaphysics of form in any number of ways, but to say that such a broad and well-developed area of philosophy is contentless would seem to simply demonstrate a total lack of familiarity with it.

C.S. Peirce, John Deely, John Poinsot, etc. have very well developed theories of the causality particular to signs and the way in which form is communicated. These theories might be misguided, but they are not reducible to "word use." Indeed, the most popular criticism of the via antiqua by those who were well acquainted with it (e.g. William of Ockham) was that it was too complex, not that it failed to say anything.

For example, Nathan Lyons "Signs in the Dust:"

[The] particular expression of intentional existence—intentional species existing in a material medium between cogniser and cognised thing— will be our focus...

In order to retrieve this aspect of Aquinas’ thought today we must reformulate his medieval understanding of species transmission and reception in the terms of modern physics and physiology.11 On the modern picture organisms receive information from the environment in the form of what we can describe roughly as energy and chemical patterns. 12 These patterns are detected by particular senses: electromagnetic radiation = vision, mechanical energy = touch, sound waves = hearing, olfactory and gustatory chemicals = smell and taste.13 When they impinge on an appropriate sensory organ, these patterns are transformed (‘transduced’ is the technical term) into signals (neuronal ‘action potentials’) in the nervous system, and then delivered to the brain and processed. To illustrate, suppose you walk into a clearing in the bush and see a eucalyptus tree on the far side. Your perception of the eucalypt is effected by means of ambient light—that is, ambient electromagnetic energy—in the environment bouncing off the tree and taking on a new pattern of organisation. The different chemical structure of the leaves, the bark, and the sap reflect certain wavelengths of light and not others; this selective reflection modifies the structure of the energy as it bounces off the tree, and this patterned structure is perceived by your eye and brain as colour....

These energy and chemical patterns revealed by modern empirical science are the place that we should locate Aquinas’ sensory species today.14 The patterns are physical structures in physical media, but they are also the locus of intentional species, because their structure is determined by the structure of the real things that cause them. The patterns thus have a representational character in the sense that they disperse a representative form of the thing into the surrounding media. In Thomistic perception, therefore, the form of the tree does not ‘teleport’ into your mind; it is communicated through normal physical mechanisms as a pattern of physical matter and energy.

The interpretation of intentions in the medium I am suggesting here is in keeping with a number of recent readers of Aquinas who construe his notion of extra-mental species as information communicated by physical means.18 Eleonore Stump notes that ‘what Aquinas refers to as the spiritual reception of an immaterial form . . . is what we are more likely to call encoded information’, as when a street map represents a city or DNA represents a protein. 19... Gyula Klima argues that ‘for Aquinas, intentionality or aboutness is the property of any form of information carried by anything about anything’, so that ‘ordinary causal processes, besides producing their ordinary physical effects according to the ordinary laws of nature, at the same time serve to transfer information about the causes of these processes in a natural system of encoding’.22

The upshot of this reading of Aquinas is that intentional being is in play even in situations where there is not a thinking, perceiving, or even sensing subject present. The phenomenon of representation which is characteristic of knowledge can thus occur in any physical media and between any existing thing, including inanimate things, because for Aquinas the domain of the intentional is not limited to mind or even to life, but includes to some degree even inanimate corporeality.

This interpretation of intentions in the medium in terms of information can be reformulated in terms of the semiotics we have retrieved from Aquinas, Cusa, and Poinsot to produce an account of signs in the medium. On this analysis, Aquinas’ intentions in the medium, which are embeded chemical patterns diffused through environments, are signs. More precisely, these patterns are sign-vehicles that refer to signifieds, namely the real things (like eucalyptus trees) that have patterned the sign-vehicles in ways that reflect their physical form.24 It is through these semiotic patterns that the form of real things is communicated intentionally through inanimate media. This is the way that we can understand, for example, Cusa’s observation that if sensation is to occur ‘between the perceptible object and the senses there must be a medium through which the object can replicate a form [speciem] of itself, or a sign [signum] of itself ’ (Comp. 4.8). This process of sensory semiosis proceeds on my analysis through the intentional replication of real things in energy and chemical sign-patterns, which are dispersed around the inanimate media of physical environments

Or there is John Deely's work, or something like Robert Sokolowski's "Phenomenology of the Human Person," etc., all of which include quite determinant statements on how form ties into perception (and language downstream of perception).

Anyhow, take a gander at: https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/987328 and I'll ask, "how is scientific knowledge possible if principles don't exist?"

Second, do things have any determinant being? If so, that's all form, in the broadest sense, is saying. To be skeptical about form in this broad sense seems to entail radical skepticism, it's to say "the properties of all things are unknowable, and indeed we cannot know if they have any determinant properties at all." But to the skeptic, I'd ask: "if things have no determinant properties, why should they cause determinant perceptions?" Particularly, given the appeal to "brains" (which does not ever produce consciousness without constant interaction with a conducive environment), why should brains ever produce one sort of cognition instead of any other if brains do not possess a determinant nature/properties? There can be no "neuroscience" if there is nothing determinant that can be said about brains.

Is there actually much difference between my 'structure' and your 'forms' (in the most generic sense of structure)? Maybe I just prefer the former word without the connotations of the latter... other similar words might be 'patterns', 'regularities', etc, etc.

Form is often described as "intrinsic structure" or "organization." Appeals to "regularities" are often reductive though, tending towards smallism. While some invocations of form are reductive, many are not.

Paul Vincent Spade's article "The Warp and Woof of Metaphysics" is a pretty good introduction on Aristotlian essences (an example of intrinsic structure) and how they tie in to predication for instance: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://pvspade.com/Logic/docs/WarpWoo1.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjt6su-mqGNAxWaw_ACHUQVOqQQFnoECCgQAQ&usg=AOvVaw1XwkMjcPAAZ0aM2Ne2b-c-

I actually mentioned the common use of "regularities" and "patterns" (always in scare quotes!) earlier in this thread. Either the Kant-like (Kant-lite?) skepticism here is absolute, and we get subjective idealism, or it isn't, and those terms must have some determinant form and content. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Right, Perl is very good on this. I suppose one of the difficulties here is the modern phobia that appearances might be arbitrarily, randomly related to appearances. Now, to appear a certain way to man is to act in a certain way, and since "act follows on being," we might suppose that things must reveal something of their reality in their appearances. The classical assumption here is that if something acts (interacts) with man in some particular way, then the definiteness of this interaction, that it is one way instead of any other, must be attributable to some prior actuality in both the thing in man. Otherwise, the phenomenological elements of the experience would be what they are "for no reason at all," or, on the side of the acting thing perceived, it would be acting for "no reason at all."

But I feel pretty safe in this assumption. If things do happen for no reason at all, if the world is not intelligible, then philosophy and science are a lost cause. However, they certainly do not seem to be lost causes.

One interesting thing to note is that this fear of arbitrariness and randomness is almost always placed on the "world/thing" side of the ledger. Yet the elevation of potency over act such a fear presupposes could apply just as well to man himself. Maybe man, his perceptual organs, his cognition, etc. is what acts entirely arbitrarily in relation to the world? We would each be "hallucinating our own world" for "no reason at all, according to not nature or prior actuality." If this seems implausible, which I think it does, I am not sure why flipping the same concern over to the "world" should be any less implausible though. -

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

Since I have no formal training in philosophy, many of its technical terms*1 are fuzzy for me. I'm pursuing this Idealistic angle on Forms*2 for my own benefit, not to convince you. Hence, my impractical question, inspired by your pragmatic/analytic*3 approach : why do some of us feel a need for Universal Concepts, when others find Particular Percepts sufficient for survival? What we sense is what is real, what we imagine is fictional. Why then, are some people motivated to seek-out feckless Fiction, when placid animals seem to be content with pragmatic Facts? In other words, Why do Philosophy?↪Gnomon

If you are saying that meaning is seen in what we do, then we agree. There's no need to invoke forms to explain what we do. We can just act. — Banno

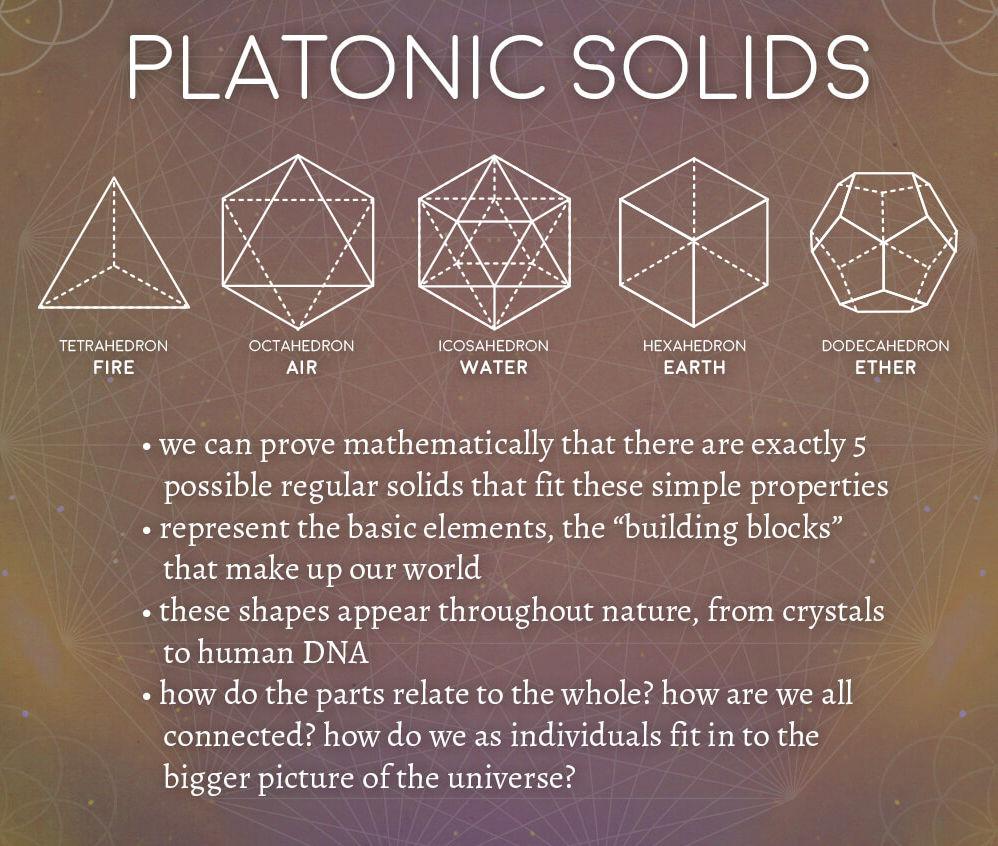

The concept of ideal Forms is not necessary or useful for Scientific purposes (doing ; acting on the world). But Philosophy (thinking ; understanding the world) goes beyond what is apparent & obvious, to discover the broader (general ; universal) meaning underlying the specific Things we see around us. For those of us who want to take meaning & significance to the limit, we quickly run into the physical restrictions of the Real world. In order to get around those barriers to liberal wisdom, we rational animals can imagine a meta-physical realm of Ideal entities, such as Gods & Forms & Mathematical Types {image below}, that are not bound by natural laws; only by abstract Logic. Such notions may have no practical applications in the Material world, but they do have profound effects in the shared Mental world of cultural concepts & beliefs, such as religions & philosophy & scientific theories.

Both Religion and Philosophy have been developed to enhance our ability to cope with the perplexities of human culture, and the complexities of the social milieu. The primary difference seems to be that Religion advises us to put our faith in the wisdom of others : Priests & Gods, while Philosophy is more of a self-help guide to personal wisdom : Stoicism & Buddhism. And Wisdom is more than a collection of Facts, it's the ability to see invisible inter-relationships, from which to create a mental map --- from a bird's perspective --- to help us navigate that labyrinthine terrain. If you can get around without a map, then you don't need that unreal imaginary fictional stuff.

For me, Meaning is not what we do (act on things), but what we think (manipulate imaginary notions). :smile:

*1A. Nominalism :Forms are not Real, in that they have no objective existence, apart from their utility for describing the objects & actions we experience. Yet we use names to efficiently communicate meanings.

B. Epiphenomenalism : Mental states are not real, but merely byproducts of brain processes.But in order to communicate those states, the physical patterns must be translated into abstract Ideal information : concepts, words, names.

C. In the context of philosophy, an epiphenomenon is a phenomenon that is caused by a primary phenomenon but does not itself cause anything. In philosophy of mind, epiphenomenalism is the view that mental states are epiphenomena, meaning they are caused by physical states in the brain but don't cause any physical events themselves.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=philosophy+eiphenomenon

D. Realism and nominalism are philosophical stances that differ in their view of abstract concepts or universals. Realists believe that universals, like "redness" or "humanity," have an objective, independent existence. Nominalists, on the other hand, assert that universals are merely names or concepts created by humans, and they don't represent an external reality.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=realism+vs+nominalism

Note --- Human History is a record of Ideas that cause change in the world. Communication of information is a causal force, not in Nature, but in human Culture. Apparently, I am a nominalist : "The beginning of wisdom is to call things by their proper name" ___Confucius

*2. Platonic Forms, in essence, serve as a foundation for understanding and accessing true knowledge and moral ideals. They provide a framework for identifying what is truly real and valuable in a world of constantly changing appearances. Forms, according to Plato, are not merely mental concepts, but have a real existence in a separate, more real world, and they are the ultimate objects of knowledge.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=why+do+we+need+platonic+forms

Parmenides, a Pre-Socratic philosopher, argued that reality is a unified, eternal, and unchanging whole, while the perception of change and multiplicity is an illusion of the senses. He proposed that "Being" is the ultimate reality, and that "non-being" is either unknowable or non-existent.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=parmenides+philosophy

Note --- Apparently for Plato, True Knowledge is universal, eternal, unchanging & rational as opposed to the local, imperfect, evolving & neurological knowledge of the physical senses. I don't know if he actually believed in a perfect Parmenidean realm, but he probably thought there ought to be something better than our directly-experienced Reality, that leaves much to be desired. Human cultural progress is based on the belief that we can make it better. Is that an impossible dream, or an inspiring aspiration?

*3. Analytic and Continental philosophy represent two distinct approaches to philosophy, primarily differentiated by their methods and areas of focus. Analytic philosophy emphasizes clarity, precision, and logic, often focusing on language, logic, and the analysis of concepts. Continental philosophy, on the other hand, is more concerned with the broad history of philosophy, human experience, and the interconnectedness of ideas.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=continental+vs+analytic+philosophy

Note --- My upbringing in the US was in the pragmatic & protestant heritage instead of the continental/catholic tradition. But in my later years, I am trying to learn about other worldviews, including the ancient Greek foundations of philosophy. In another post, I may attempt to make sense of 50,000 year old Aboriginal philosophy, with its otherworldly Dreamtime.

IDEAL FORMS ARE IMAGINARY & MATHEMATICAL, NOT ACTUAL & MATERIAL

The postulated elements are symbolic not physical

-

Banno

30.6kThanks for that post. A different take, but perhaps not too dissimilar to what I have been suggesting.

Banno

30.6kThanks for that post. A different take, but perhaps not too dissimilar to what I have been suggesting.

Interesting that you mention strange loops. You've read Hofstadter, I presume? -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

This might be the key here. Those who "feel an need for Universal Concepts" will make an unjustified jump to them. It'll be a transcendental argument: things are thus-and-so; the only way they can be thus-and-so is if this Universal Concept is in play; therefore......why do some of us feel a need for Universal Concepts, when others find Particular Percepts sufficient for survival? — Gnomon

Btu that's perhaps psychology rather than philosophy. The philosophical response will be limited to showing that the second premise is mistaken, that there may be other ways that things can be thus-and-so, or perhaps that they just are thus-and-so, without the need for further justification.

The admonition is that in order to understand meaning, look to use. In order to understand what folk think, look to what they do. And here, include what they say as a part of what they do.For me, Meaning is not what we do (act on things), but what we think (manipulate imaginary notions). :smile: — Gnomon

So it's not either-or; not a choice between what we do and what we think. Rather it's a method to clarify and clean up the mess of words that constitutes philosophical conversation.

See 's post, which brings out further your observation that forms do not much help us.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Plato vs Aristotle (Forms/forms)

- Buddha's Nirvana, Plato's Forms, Schopenhauer's Quietude

- Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

- Should troll farms and other forms of information warfare be protected under the First Amendment?

- An objection to the Teleological Argument: Other forms of life

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum