-

Wayfarer

26.2kIdealism In Context

Wayfarer

26.2kIdealism In Context

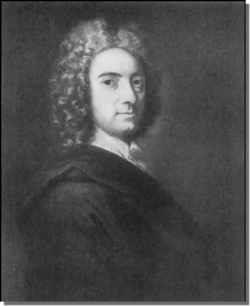

Bishop George Berkeley 1685– 1753

Abstract: Berkeley’s idealism should be reinterpreted not as an outmoded metaphysical theory, but as a philosophically astute protest against the “great abstraction” initiated by the scientific revolution — a defense of the primacy of experience and the indispensability of the observer, in a historical moment when knowledge was being severed from consciousness in favor of a disembodied ‘view from nowhere’.

The Philosopher of the Immaterial

George Berkeley (1685–1753) was an Irish philosopher and Anglican bishop best known for his philosophy of immaterialism — the view that physical objects exist only if perceived (summed up in the memorable aphorism ‘esse est percipi’). Though sometimes dismissed as a mere eccentric for denying the reality of matter, Berkeley was in fact a rigorous and highly influential thinker, engaging deeply with the scientific and philosophical debates of his time. His works display sharp reasoning, lucid prose, and a deep insight into the limits of human knowledge. Influential philosophers such as David Hume, Immanuel Kant, and even modern cognitive scientists have taken his arguments seriously, whether to extend them or to refute them. Far from being a marginal figure, Berkeley stands as one of the great early modern philosophers, grappling with many of the same epistemological and metaphysical problems that remain central today.

So Does a Tree Fall in the Forest?

George Berkeley’s central philosophical claim is that to be is to be perceived (esse est percipi). He denies the existence of mind-independent matter — not the reality of the world itself, but the idea that it exists apart from perception. According to Berkeley, all sensible objects — colors, sounds, shapes, and so on — exist only insofar as they are perceived by a mind. (This is the subject of the philosophical riddle, if a tree falls in the forest when nobody is there to see it, does it really fall?) Berkeley says what we call the “external world” consists of ideas within the minds of observers, and ultimately within the divine mind of God, who guarantees the continuity and coherence of experience.

Berkeley was keen to stress that he did not deny the reality of the world as such. In his own words:

I do not argue against the existence of any one thing that we can apprehend, either by sense or reflection. That the things I see with my eyes and touch with my hands do exist, really exist, I make not the least question. The only thing whose existence we deny is that which philosophers call ‘matter’ or ‘corporeal substance’. ¹

What Berkeley objected to was the notion of an unknowable stuff underlying experience — an abstraction he believed served no explanatory purpose and in fact led to skepticism. His philosophy was intended as a corrective to this, affirming instead that the world is as it appears to us in experience — vivid, structured, and meaningful, but always in relation to a mind — although importantly for Berkeley, as a Christian Bishop, the mind of God served as a kind of universal guarantor of reality, as by Him all things were perceived, and so maintained in existence.

The Matter with Matter

We noted above that what Berkeley denies is not the reality of the objects of sense, but of a material substance — something which underlies and stands apart from the objects it comprises. Much ink has been and can be spilled on this question, but the point of this essay is to situate Berkeley’s objection to material substance in its historical context.

The earlier philosophy of St Thomas Aquinas, building on Aristotle, maintained that true knowledge arises from a real union between knower and known. As Aristotle put it, “the soul (psuchē) is, in a way, all things,”² meaning that the intellect becomes what it knows by receiving the form of the known object. Aquinas elaborated this with the principle that “the thing known is in the knower according to the mode of the knower.”³ In this view, to know something is not simply to construct a mental representation of it, but to participate in its form — to take into oneself, immaterially, the essence of what the thing is. (Here one may discern an echo of that inward unity — a kind of at-one-ness between subject and object — that contemplative traditions across cultures have long sought, not through discursive analysis but through direct insight.) Such noetic insight, unlike sensory knowledge, disengages the form of the particular from its individuating material conditions, allowing the intellect to apprehend it in its universality. This process — abstraction— is not merely a mental filtering but a form of participatory knowing: the intellect is conformed to the particular, and that conformity gives rise to true insight. Thus, knowledge is not an external mapping of the world but an assimilation, a union that bridges the gap between subject and object through shared intelligibility.

By contrast, the word objective, in its modern philosophical usage — “not dependent on the mind for existence” — entered the English lexicon only in the early 17th century, during the formative period of modern science, marked by the shift away from the philosophy of the medievals. This marks a profound shift in the way existence itself was understood. As noted, for medieval and pre-modern philosophy, the real is the intelligible, and to know what is real is to participate in a cosmos imbued with meaning, value, and purpose. But in the new, scientific outlook, to be real increasingly meant to be mind-independent — and knowledge of it was understood to be describable in purely quantitative, mechanical terms, independently of any observer. The implicit result is that reality–as–such is something we are apart from, outside of, separate to.

This conceptual shift took decisive form in the work of Galileo, Descartes, and John Locke (against whom most of Berkeley’s polemics were directed). Galileo proposed that the “book of nature” is written in the language of mathematics, and that only its measurable attributes — shape, number, motion — belonged to nature herself⁴. Qualities like color, taste, or warmth, by contrast, were real only in the eye of the observer. Descartes then systematized this intuition into the dualism of res extensa (extended substance, or matter) and res cogitans (thinking substance, or mind). Nature became the domain of extension and motion; mind, the domain of thought and experience.

John Locke echoed Galileo’s division with his doctrine of primary and secondary qualities: the former (solidity, extension, number, motion) were intrinsic to objects; the latter (color, sound, taste) were the result of subjective experience⁵. In this view, “objective reality” is what remains when all the qualities contributed by the mind are stripped away. So, from the participatory knowledge of the Medievals, in this development, the domains of the objective and subjective became utterly separated (a conundrum which Descartes himself recognised but was never able to really solve).

But this conceptual division, for all the scientific power it was to deliver, came at a cost. As Husserl would much later argue in The Crisis of European Sciences⁶, it negates the role of the subject — the experiencing, meaning-giving mind — by treating reality as though it could be fully understood apart from the subject— the very subject to whom it conveys meaning. Ancient geometry, Husserl observed, dealt with finite and concrete tasks, rooted in the intuitive understanding of forms, represented in classical architecture. Modern science, by contrast, generated a “rational infinite totality of being,” where the world is modeled not as it is lived or experienced by a subject, but as it has been abstracted for quantitative analysis, and in which the subject no longer figures.

The great abstraction that Husserl critiques is precisely the one underlying the modern idea of objectivity: a mathematically tractable reality that brackets out the observer, on the grounds that the object of analysis is the same for all observers. And it is in this context that we find the origin of the modern conception of material substance — an understanding by now so deeply embedded in our culture that to question it is to be accused of ignoring reality.

This is the geneology of how philosophical idealism arose in response to the disclocation introduced by the Scientific Revolution. With the advent of the new sciences, especially in the mechanistic philosophies of Galileo, Descartes, and Newton, the participatory sense of being and knowing was replaced by a dualistic one: the world becomes res extensa, a realm of extension and quantity, while the mind becomes res cogitans, the individual ego only certain of their own existence. The epistemological consequence is a representational theory of knowledge, in which the observer can only infer facts about the external world from inner ideas — an approach that severs the vital bond between mind and world.

In this analysis, idealism emerges not to deny the reality of the world, but to restore coherence and meaning by re-asserting the role of the observing mind. Importantly, there had been no need for the pre-moderns to advocate such a philosophy, because the division that idealism sought to ameliorate had not yet occured.

The Enduring Relevance of Kant

In this context, the great Immanuel Kant stands as a pivotal figure. He stands at the crossroads between early modern science and later philosophy. While he fully acknowledged the power and success of Newtonian science, he refused to reduce the human being to mere object within that system. As Emrys Westacott writes, “Kant never lost sight of the fact that while modern science is one of humanity’s most impressive achievements, we are not just knowers: we are also agents who make choices and hold ourselves responsible for our actions… But a danger carried by the scientific understanding of the world is that its power and elegance may lead us to undervalue those things that don’t count as science.”⁷ For Kant, the capacity for moral action, the experience of beauty, and the sense of wonder are not reducible to empirical description. They are constitutive of our humanity, and any philosophical account that ignores them fails to do justice to the full scope of human experience.

Kant criticized Berkeley (who had preceded him) and was irritated when critics accused him of simply rehashing Berkeley’s ideas. Nevertheless both philosophers were responding — each in their own way — to the same historical rupture: the advent of a conception of reality that utterly excluded the subject. Without going into detail of Kant’s criticisms, the essential point is that both forms of idealism emerged as reactions to the same deep shift in how knowledge and existence were understood in the wake of the Scientific Revolution.

Idealism Redux

With the benefit of hindsight, at least some of Berkeley’s philosophy remains plausible. In On Physics and Philosophy (2006), physicist Bernard d’Espagnat refers to Bishop Berkeley — not to endorse his immaterialism, but to acknowledge that quantum theory has unsettled the once-unquestioned assumption of an observer-independent reality⁸. Paradoxically, a scientific revolution formerly anticipated as the pinnacle of physical realism ends up reviving precisely the kind of metaphysical questions Berkeley posed in the early 18th century!

D’Espagnat recognizes the enduring relevance of Berkeley’s line of inquiry: What is the ontological status of the unobserved? Can we meaningfully speak of a world existing wholly apart from perception? Resolutions to these questions remain surprisingly elusive.

As d’Espagnat famously observed, quantum physics suggests that “reality is not wholly real” in the classical sense presupposed by scientific realism. In this, it echoes — though it does not replicate — Berkeley’s insight that the so-called external world may lack an ontological ground apart from perception. For both thinkers, in very different idioms, the role of the observer — whether as ‘mind’ or ‘spirit’ in Berkeley, or as measurement and observation in quantum physics — proves central. Indeed, the apparent indispensability of the observer (or at least the act of measurement), has become a pivotal philosophical issue in contemporary physics.

However, by the early 20th century, philosophical idealism fell out of favor — particularly in the English-speaking world — under pressure from the rising influence of logical positivism, linguistic analysis, and a growing faith in scientific realism. It came to be regarded, often unfairly, as speculative, obsolete, or even incoherent.

Yet the questions that animated idealist thought never went away. In continental philosophy, the legacy of idealism continued through phenomenology, existentialism, and post-structuralism. Thinkers like Husserl, Heidegger, and Merleau-Ponty explored in various ways the structures of experience, the situatedness of subjectivity, and the impossibility of a fully detached, ‘view from nowhere.’⁹

More recently, developments in cognitive science — especially the enactivist and embodied mind approaches — have returned to questions about the relationship between perception, subjectivity, and world. These frameworks reject the idea of a passive mind merely representing a pre-given reality, and instead emphasize the co-constitution of mind and world through lived activity.

In this way, the concerns of idealism re-emerge, not as nostalgic metaphysics, but as a vital part of understanding what it means to experience, to know, and to be — the core concerns of philosophy, if not always of science. Bernardo Kastrup¹⁰ has emerged as an articulate defender of philosophical idealism, although of the earlier philosophers he is nearer in approach to Arthur Schopenhauer than to Berkeley. Idealism certainly retains a place at the table, in dialogue with the various other schools and trends in modern philosophical thought, and is, as noted, associated with some influential interpretations of quantum physics.

But to understand why idealism is important, we need to be clear about what prompted its emergence in the early modern period, and what about it remains relevant. That is what I hope this brief essay has introduced.

Bibliography and References

[1]Berkeley, George. Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous, edited by Robert M. Adams, Hackett Publishing, 1979. Also see Early Modern Texts

[2]Aristotle, De Anima, III.8, 431b21. Trans. Hugh Lawson-Tancred (London: Penguin Classics, 1986)

[3]Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, I, q. 12, a. 4. Trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (New York: Benziger Bros., 1947)

[4]Galileo Galilei, Il Saggiatore (The Assayer), 1623. Translation from Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo, ed. Stillman Drake, Anchor Books, 1957.

[5]John Locke. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, edited by Peter H. Nidditch (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), II.viii.9.

[6]Edmund Husserl. The Crisis of the European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology: An Introduction to Phenomenological Philosophy, trans. David Carr (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1970)

[7]Westacott, Emrys. The Continuing Relevance of Immanuel Kant (retrieved 1 July 2025)

[8]d’Espagnat, Bernard. On Physics and Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006.

[9]Nagel, Thomas. The View from Nowhere. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

[10]Bernardo Kastrup, Analytical Idealism in a Nutshell (Hants, UK: Iff Books, 2022).

Also posted on Medium. -

180 Proof

16.5k

180 Proof

16.5k

Perhaps, as "Schrödinger Cat" as well as e.g. Einstein, Popper, Hawking, Penrose, Deutsch et al suggest, "quantum physics" provides an extremely precise yet mathematically incomplete model of "reality" – how does quantum measurement happen? – that is (epistemically?) inconsistent with classical scale scientific realism (re: definite un/observables / locality). I suspect, 'absent solving 'the measurement problem', physicists like d’Espagnat make a metaphysical Mind-of-the-gaps faux pas.As d’Espagnat famouslyobserved[assumed], quantum physics suggests that “reality is not wholly real” in the classical sense presupposed by scientific realism. — Wayfarer -

L'éléphant

1.8kThanks for the summary of the unfolding of the enlightenment period.

L'éléphant

1.8kThanks for the summary of the unfolding of the enlightenment period.

By contrast, the word objective, in its modern philosophical usage — “not dependent on the mind for existence” — entered the English lexicon only in the early 17th century, during the formative period of modern science, marked by the shift away from the philosophy of the medievals. This marks a profound shift in the way existence itself was understood. As noted, for medieval and pre-modern philosophy, the real is the intelligible, and to know what is real is to participate in a cosmos imbued with meaning, value, and purpose. But in the new, scientific outlook, to be real increasingly meant to be mind-independent — and knowledge of it was understood to be describable in purely quantitative, mechanical terms, independently of any observer. The implicit result is that reality–as–such is something we are apart from, outside of, separate to.

This conceptual shift took decisive form in the work of Galileo, Descartes, and John Locke (against whom most of Berkeley’s polemics were directed). Galileo proposed that the “book of nature” is written in the language of mathematics, and that only its measurable attributes — shape, number, motion — belonged to nature herself⁴. — Wayfarer

Berkeley was part of the enlightenment movement, Descartes was prior to the enlightenment.

Berkeley was right to denounce realism and the objective reality because the root source of it was imbued in mysticism and mythology. (Hint: the Anglican religion did not and does not subscribe to mysticism and mythology). The pre-socratics were considered "scientific" in the sense that they refer to "nature" as something apart from the observers. But in doing so, (1) they had to employ a lot of mysticism and mythology. Without Physics, we wonder how and why they were described as scientific.

(2) Add to it the naive realism -- a belief that advocates that we see is what actually exists out there. It does not allow any doubt as to the verity of our perception. And we know we also do not subscribe to it.

(3) Finally, a mechanical world where only numbers, shape, motion ignores the observers entirely. We belong in the world, as tangible, perceptible objects that have a central doing in existence.

Good job writing this OP. -

RussellA

2.7kGeorge Berkeley....................best known for his philosophy of immaterialism — the view that physical objects exist only if perceived — Wayfarer

RussellA

2.7kGeorge Berkeley....................best known for his philosophy of immaterialism — the view that physical objects exist only if perceived — Wayfarer

Humans cannot perceive Black Holes.

They may be inferred, but they cannot be perceived in Berkeley's terms.

Would it be Berkeley's position that Black Holes don't exist? -

Apustimelogist

946

Apustimelogist

946

I distinctly remember my impression of Berkeley from university was that he had quite scientific mind, he had sharp, cogent arguments. However, he was a Bishop after all. I like to believe that if he didn't have God, and access to modern science instead, he would have been more on my side of the debate.

What Berkeley objected to was the notion of an unknowable stuff underlying experience — an abstraction he believed served no explanatory purpose and in fact led to skepticism. His philosophy was intended as a corrective to this, affirming instead that the world is as it appears to us in experience — Wayfarer

This is not so different from my objections to your insistence on some mysterious divide between phenomenal and noumenal. I don't think his arguments were out of some fundamental distate of objectivity and bias toward subjective woo. I think if he had been around in the early twentieth century he would have been a logical positivist and then made the natural adjustments in light of post-positivism. I don't think he would have been a Deepak Chopra fan. -

boundless

760What Berkeley objected to was the notion of an unknowable stuff underlying experience — an abstraction he believed served no explanatory purpose and in fact led to skepticism. His philosophy was intended as a corrective to this, affirming instead that the world is as it appears to us in experience — vivid, structured, and meaningful, but always in relation to a mind — although importantly for Berkeley, as a Christian Bishop, the mind of God served as a kind of universal guarantor of reality, as by Him all things were perceived, and so maintained in existence. — Wayfarer

boundless

760What Berkeley objected to was the notion of an unknowable stuff underlying experience — an abstraction he believed served no explanatory purpose and in fact led to skepticism. His philosophy was intended as a corrective to this, affirming instead that the world is as it appears to us in experience — vivid, structured, and meaningful, but always in relation to a mind — although importantly for Berkeley, as a Christian Bishop, the mind of God served as a kind of universal guarantor of reality, as by Him all things were perceived, and so maintained in existence. — Wayfarer

Yes, according to Berkeley phenomena are mere appearances. There is nothing 'more' than 'what appears' to the mind. But notice that Berkeley explained things like (i) the intersubjective validity of empirical truths (e.g. scientific truths but not only that), (ii) persistence and stability of the 'world' (e.g. why, say, there aren't drastic changes of what we experience from a day to the following), (iii) the regularities of the 'world' (e.g. 'laws' of physics) and so on by appealing to God. God assures that we, both individually and collectively, have a consistent experience.

Kant, however, didn't want to explain any of the above by appealing to God. In fact, he said that it is the structure of our mental faculties that give us a structure, regulated etc phenomenal world becuase our minds condition appearances to have some characteristics. Since, however, appearances could not be generated completely by the subject, Kant still assumed that there is a non-phenomenal reality but it is unknowable. This unknowability is the reason why Kant isn't regarded as a 'realist' but as a 'transcendental idealist'.

The main problem with this, however, is that there is no sufficient evidence for us to claim that the stability, regularities etc can be wholly explained by the role that the mind has in 'ordanining' appearances. Same goes for intersubjectivity. It is not enough to say that we have 'similar minds' to wholly explain why the 'phenomenal world' appears similar to all of us. Furthermore, if the 'reality beyond/prior to phenomena' is unknowable, how could our cognitive faculties be able to 'order' appearances in the first place?

Notice that d'Espagnat disagreed with Kant here. In fact, he did believe that we can know, albeit partially and confusedly, the reality beyond phenomena (as 'through a glass darkly' to use a Biblical expression in a different context). Such a reality is veiled but not entirely inaccessible. Just like we can know in part and in a confused manner the features of a veiled statue by touching it, in the same way by studying phenomena, according to d'Espagnat, we can know the 'veiled reality'. So, while d'Espagnat's philosophy has many similarities to Kant's, they differ and, in fact, d'Espagnat's position is realist - a realism that, of course, share many things with transcendental idealism (and quite likely influenced by it) but still a realism (of a very paticular kind).

A similar thing is seen among cognitive scientists IMO. They recognize the ability of the mind to 'give a structure' to experience. The mind isn't a passive recorder of 'what happens' but an active interpreter. But IMO they do not go as far as Kant.

I agree, however, that transcendental/epistemic idealist philosophies did influece cognitive scientists (and not only them... undoubdetly they influeced also various physicists, especially starting from the 20th century). So, the importance of these philosophical approaches should not be understimated. In fact, I do believe that they can be (and had been) a source of inspiration for discoveries.

(Good OP btw) -

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

Berkeley's Idealism may still be a relevant metaphysical theory, but the general physical understanding has evolved beyond primitive Materialism since the 17th century. For example, I'm currently reading a science/philosophy book by James Glattfelder --- physicist, financial quant, and complexity theorist --- The Sapient Cosmos. A key conclusion is that the physical universe is guided by a Teleological Purpose, somewhat more cryptic than the Genesis gene-centric command : "be fruitful and multiply . . . . fill the Earth and subdue it".Abstract: Berkeley’s idealism should be reinterpreted not as an outmoded metaphysical theory, but as a philosophically astute protest against the “great abstraction” initiated by the scientific revolution — a defense of the primacy of experience and the indispensability of the observer, in a historical moment when knowledge was being severed from consciousness in favor of a disembodied ‘view from nowhere’. — Wayfarer

He includes a chapter entitled, A New Perspective, which reviews "The Demise of Physicalism" and "the Rise of Idealism". The chapter discusses Information-Theoretic Theories of Everything (e.g. Tononi's IIT), the Analytical Idealism of Kastrup, and several other unorthodox worldviews that place cosmic Mind over Mundane Matter. But his preferred MoMM philosophy seems to be Syncretic Idealism*1, which incorporates a variety of interpretations of the role of Mind, Consciousness, and Information in the post-quantum world*2.

I am leaning in a similar direction, but I'm not sure I can agree with some of the theorists' surreal interpretations of a Sapient Cosmos. Are you familiar with these cutting-edge updates of Berkeley's model of a Mind Created World? Do you think the Cosmos is currently Conscious, or is it evolving toward Collective Sentience, or was the First Cause of the evolutionary program Sentient in some sense? :smile:

*1. Syncretic idealism is a philosophical proposition that combines aspects of various forms of idealism with elements from other philosophical systems and insights from physics, particularly information theory. It aims to create a unified worldview by integrating concepts previously considered in isolation, offering a new understanding of reality, information, consciousness, and meaning. Essentially, it's a way of synthesizing different philosophical ideas to create a more comprehensive and coherent picture of existence. . . . .

Syncretic idealism often incorporates concepts like:

# Ontology: The study of being and existence, with syncretic idealism proposing a multi-tiered ontology that bridges the gap between abstract potentiality and concrete actuality.

# Information Theory: Drawing from physics, it emphasizes the role of information in shaping reality and the universe's structure.

# Consciousness: A central element, with syncretic idealism exploring the emergence of consciousness and its role in a sentient cosmos.

# Teleology: The idea of a guiding force or purpose in the universe, with syncretic idealism suggesting a "will to complexity" that drives the evolution of the cosmos

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=syncretic+idealism

*2. The aim of the chapter is to gently introduce the reader to all the concepts heavily condensed into the following information-rich sentence: Syncretic idealism presents a multi-tiered ontology, describing the transition from abstract quantum potentiality to the manifestation of complex actuality, outlining the assembly of physicality from the ontological fields of information fueling the computational engine at the core of reality, unveiling a teleological ordering force — a will to complexity — sculpting manifestations of increasing complexity resulting in sapience and disclosing the final emergence of dissociated centers of consciousness, yielding a sentient cosmos.

https://medium.com/@jnode/the-sapient-cosmos-in-a-nutshell-02c3479cca4b -

Wayfarer

26.2kPerhaps, as "Schrödinger Cat" as well as e.g. Einstein, Popper, Hawking, Penrose, Deutsch et al suggest, "quantum physics" provides an extremely precise yet mathematically incomplete model of "reality" — 180 Proof

Wayfarer

26.2kPerhaps, as "Schrödinger Cat" as well as e.g. Einstein, Popper, Hawking, Penrose, Deutsch et al suggest, "quantum physics" provides an extremely precise yet mathematically incomplete model of "reality" — 180 Proof

Terrence Deacon did call his book Incomplete Nature. Maybe he's onto something!

(3) Finally, a mechanical world where only numbers, shape, motion ignores the observers entirely. We belong in the world, as tangible, perceptible objects that have a central doing in existence. — L'éléphant

Quite! That is a central point in this topic. Except I would say 'subjects' rather than 'objects'.

if the 'reality beyond/prior to phenomena' is unknowable, how could our cognitive faculties be able to 'order' appearances in the first place? — boundless

Kant doesn’t say our faculties impose order on “reality in itself” — only on the raw manifold of intuition as it is given to us. The in-itself is the source of that, but its true nature remains unknowable; what we know is the ordered phenomenal field that results from the mind’s structuring of the manifold of sensory impressions in accordance with its a priori forms and concepts.

I'm aware that D'Espagnat differed with both Kant and Berkeley, but he did mention both. Berkeley's idealism is often mentioned by physicists as representing a kind of idealism that they wish to differentiate themselves from. But the point is - he's mentioned!

I think if he had been around in the early twentieth century he would have been a logical positivist and then made the natural adjustments in light of post-positivism. — Apustimelogist

What an odd statement! Berkeley's metaphysical idealism is polar opposite to logical positivism's hardline materialism. Berkeley is much more ilkely to have returned as a Bernardo Kastrup or James Glattfelder than as Freddie Ayer. (I keep well away from Deepak Chopra.)

The Sapient Cosmos. — Gnomon

Published by Essentia Foundation, which is Kastrup's publishing house. I like Glattfelder but my interests are a little more prosaic, he's a bit too far out when he gets into shamanism and psychedelics. But, from the Medium essay you linked to:

physicalism has unwittingly been adopted by most scientifically-minded people who believe it to be a scientific claim. This, however, is a category mistake, as it conflates the descriptive scope of science with a metaphysical claim about the ultimate nature of reality. — James Glattfelder

Check!

Do you think the Cosmos is currently Conscious, or is it evolving toward Collective Sentience, or was the First Cause of the evolutionary program Sentient in some sense? — Gnomon

The way I think of it is that there may well be a latent tendency in the Cosmos towards the kinds of conscious awareness that manifests through evolutionary development. And actually that's not too far out - it is an idea that was entertained in the mid-20th Century by Julian Huxley, scion of the eminent Huxley family:

Man is that part of reality in which and through which the cosmic process has become conscious and has begun to comprehend itself. His supreme task is to increase that conscious comprehension and to apply it as fully as possible to guide the course of events. In other words, his role is to discover his destiny as an agent of the evolutionary process, in order to fulfill it more adequately. — Julian Huxley, Religion without Revelation, (London: Max Parrish, 1959), 236. -

Wayfarer

26.2kMany interesting comments here, for which I'm grateful, but the main point of the OP has slipped by.

Wayfarer

26.2kMany interesting comments here, for which I'm grateful, but the main point of the OP has slipped by.

The modern notion of a “mind-independent reality” — a world existing in isolation from any intellect — is a distinctly post-Cartesian development. In Scholasticism, exemplified by Aquinas, reality (more precisely being, ens) was intelligible because it participated in the Divine Intellect, and knowledge was understood as the mind’s assimilation to the forms — a framework wholly unlike early modern scientific realism. And this is no accident: thinkers from Descartes onward sought to differentiate themselves from “the schoolmen.”

It was this emerging “mind-independent reality” that Berkeley and Kant each, in their own way, set out to challenge — not by reviving the Scholastic participatory realism, but by criticising the new division between an unknowable material substance and the world as it appears to subjects. That division opened the conceptual chasm between mind and world that underlies the “Cartesian anxiety” of modernity. -

Apustimelogist

946Berkeley's metaphysical idealism is polar opposite to logical positivism's hardline materialism. — Wayfarer

Apustimelogist

946Berkeley's metaphysical idealism is polar opposite to logical positivism's hardline materialism. — Wayfarer

But they weren't necessarily materialists, they were first and foremosts empiricists who wanted to constrain what could be talked about in terms of observation. Logical positivism was related to phenomenalism. I don't think he would have been impressed with Kastrup's view which seems to always be alluding to something mysterious under the hood. -

Wayfarer

26.2kYes, but the positivists detested metaphysics. How would Berkeley have been received, explaining that everything is kept in existence by being perceived by God, in that environment?

Wayfarer

26.2kYes, but the positivists detested metaphysics. How would Berkeley have been received, explaining that everything is kept in existence by being perceived by God, in that environment?

I don't think he would have been impressed with Kastrup's view which seems to always be alluding to something mysterious under the hood. — Apustimelogist

Bernardo Kastrup never says that. His analytical idealism says that the reality of phenomenal experience is the fundamental fact of existence. -

RogueAI

3.5kHumans cannot perceive Black Holes.

RogueAI

3.5kHumans cannot perceive Black Holes.

They may be inferred, but they cannot be perceived in Berkeley's terms.

Would it be Berkeley's position that Black Holes don't exist? — RussellA

I'm not sure about that. The gravity waves from black hole collisions can be perceived via gravity wave detection. Wouldn't that put them in the same category as, say, neutron stars? -

Apustimelogist

946Yes, but the positivists detested metaphysics. How would Berkeley have been received, explaining that everything is kept in existence by being perceived by God, in that environment? — Wayfarer

Apustimelogist

946Yes, but the positivists detested metaphysics. How would Berkeley have been received, explaining that everything is kept in existence by being perceived by God, in that environment? — Wayfarer

Well, in my scenario, he doesn't believe in God anymore. And as much as postivists detest metaphysics maybe Berkeley also detested talk about things that seem to speculatively go beyond what is in appearance which is just what one experiences. Seems like a parallel.

Bernardo Kastrup never says that. His analytical idealism says that the reality of phenomenal experience is the fundamental fact of existence. — Wayfarer

He is always saying that. I have seen him talk about quantum theory and about how he thinks the alleged falsification of "realism" there is some kind of indication that these physical things are only appearances and whats really going on is something deeper. And then he starts talking about diasociative alters and all this nonsense. -

Wayfarer

26.2kAs regards black holes, Berkeley doesn’t reject inductive inference; in fact, his Principles of Human Knowledge and Three Dialogues show that he accepts the regularities of experience and the way we extend them to predict or explain things we haven’t directly sensed. He just interprets those regularities very differently from the material realist.

Wayfarer

26.2kAs regards black holes, Berkeley doesn’t reject inductive inference; in fact, his Principles of Human Knowledge and Three Dialogues show that he accepts the regularities of experience and the way we extend them to predict or explain things we haven’t directly sensed. He just interprets those regularities very differently from the material realist.

have seen (Kastrup) talk about quantum theory and about how he thinks the alleged falsification of "realism" there is some kind of indication that these physical things are only appearances and whats really going on is something deeper. — Apustimelogist

His first employment was at CERN, and I think he qualifies as expert in the field. He says "if you are close to the foundations of physics – and at CERN we were dealing with the most fundamental part of the most fundamental science – you get used to thinking in abstractions, and to the idea that things are not fundamentally concrete. If you look deep enough into the heart of matter, all concreteness vanishes, and what is left is a pure mathematical abstraction that we call fields – quantum fields. And what is a quantum field? A quantum field is a mathematical tool which is postulated because the world behaves as if it exists. But that doesn’t mean that people at CERN have actually found a quantum field or touched one.

This is true even of the so-called Higgs boson, which has got a lot of press in recent years. People think that we managed to capture one, or photograph one, or even measure one directly at CERN. But that’s not how it works. The Higgs, whatever it is, decays before it interacts with measurement equipment. What we measure is the debris that it turns into after it decays. We sort of theoretically reconstruct from that what should have been the Higgs, because we don’t have any other explanation for the debris we measure. So although I didn’t start thinking about idealist theories when I was at CERN, it did prepare me to part easily with the core intuition that matter has a concrete existence. Even as a materialist, I already knew that that was not the case."

As for his dissociated alters - I'm not totally convinced by it, but I also don't believe it nonsensical. -

Apustimelogist

946His first employment was at CERN — Wayfarer

Apustimelogist

946His first employment was at CERN — Wayfarer

I really doubt he qualifies as an expert in the field. He doesn't seem to have a physics PHD. "Realism" is also more interpretational / foundational and less to do with what people do at CERN, nor is there consensus on it, I believe. -

Wayfarer

26.2kHe doesn't seem to have a physics PHD. — Apustimelogist

Wayfarer

26.2kHe doesn't seem to have a physics PHD. — Apustimelogist

Oh, only two Phd's, one in computer science, other in philosophy of mind. Poor dude, wonder he can tie his shoes in the morning. -

Apustimelogist

946

Apustimelogist

946 -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe question of interpretion of physics is as much one of philosophy as of physics. And Kastrup has got considerable practical experience in physics - 'His role involved working on the "trigger" system for the ATLAS experiment, which is one of the main experiments of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) project. The job required him to design and program specialized computer systems that could automatically decide in a fraction of a second whether a subatomic collision was significant enough to save for later analysis or to discard.'

Wayfarer

26.2kThe question of interpretion of physics is as much one of philosophy as of physics. And Kastrup has got considerable practical experience in physics - 'His role involved working on the "trigger" system for the ATLAS experiment, which is one of the main experiments of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) project. The job required him to design and program specialized computer systems that could automatically decide in a fraction of a second whether a subatomic collision was significant enough to save for later analysis or to discard.' -

Janus

18kWe noted above that what Berkeley denies is not the reality of the objects of sense, but of a material substance — something which underlies and stands apart from the objects it comprises. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kWe noted above that what Berkeley denies is not the reality of the objects of sense, but of a material substance — something which underlies and stands apart from the objects it comprises. — Wayfarer

Why would it be thought that material substance "stands apart from the objects it comprises" if it is what constitutes them? This looks like a strawman.

Kant doesn’t say our faculties impose order on “reality in itself” — only on the raw manifold of intuition as it is given to us. — Wayfarer

What is given to the senses cannot plausibly, or even coherently, be thought to be unstructured, undifferentiated in itself and yet give rise to a shared world of phenomena. If all the differentiation and structure originated with the individual human subject the fact of a shared world becomes inexplicable, unless a collective or universal mind be posited, and it is precisely that (God) which Berkeley posits.

Such a universal mind (deity) is a thinkable possibility as is a fundamental substance (matter/ energy) of which all things are constituted. The salient question is which seems the more plausible, and since there is no strict measure of plausibly, the answer to that will vary among folk.

Should we take science as our guide to determine which seems more plausible, or should we take our imagination, intuitions, feelings and wishes? -

Wayfarer

26.2kWhy would it be thought that material substance "stands apart from the objects it comprises" if it is what constitutes them? — Janus

Wayfarer

26.2kWhy would it be thought that material substance "stands apart from the objects it comprises" if it is what constitutes them? — Janus

Recall that in the early modern scientific model, the measurable attributes of bodies were said to be different from how the object appeared to the senses. This is central to the 'great abstraction' of physics that Berkeley was criticising.

Should we take science as our guide to determine which seems more plausible, or should we take our imagination, intuitions, feelings and wishes? — Janus

Perhaps we could study philosophy, and also study philosophically, rather than referring everything to science as the arbiter of reality. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kShould we take science as our guide to determine which seems more plausible, or should we take our imagination, intuitions, wishes and so on? — Janus

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kShould we take science as our guide to determine which seems more plausible, or should we take our imagination, intuitions, wishes and so on? — Janus

Science provides no guidance on this. It is a metaphysical question. The fundamental matter/energy assumption falls to infinite regress in scientific experimentation. Since science demonstrates that fundamental matter/energy is problematic, the deity is posed as an end to the infinite regress. So science gives us no guidance as to which is more plausible. Neither, the infinite regress of matter/energy nor the deity is supported by science. -

Janus

18kRecall that in the early modern scientific model, the measurable attributes of bodies were said to be different from how the object appeared to the senses. This is central to the 'great abstraction' of physics that Berkeley was criticising. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kRecall that in the early modern scientific model, the measurable attributes of bodies were said to be different from how the object appeared to the senses. This is central to the 'great abstraction' of physics that Berkeley was criticising. — Wayfarer

I'm not sure how you are relating what you say here to the point I made. The idea of fundamental constituents of material objects has been around since Democritus, and as far as I know, those constituents had, until fairly recent times, never been thought to be measurable, and in any case a fundamental limit of measurability has been determined (the Planck length). Rather it would seem to be how the object appears to the senses that is, potentially at least, measurable.

Perhaps we could study philosophy, and also study philosophically, rather than referring everything to science as the arbiter of reality. — Wayfarer

It is not that science is the "arbiter of reality'―the question is rather as to what our metaphysical speculations and conclusions should be guided by.

Science provides no guidance on this. It is a metaphysical question. The fundamental matter/energy assumption falls to infinite regress in scientific experimentation. — Metaphysician Undercover

I could equally say that imagination, intuitions, feelings and wishes provide no guidance on metaphysical questions.

Do you have a reference or an argument for your 'fundamental matter/ energy' claim? -

Apustimelogist

946The question of interpretion of physics is as much one of philosophy as of physics. And Kastrup has got considerable practical experience in physics — Wayfarer

Apustimelogist

946The question of interpretion of physics is as much one of philosophy as of physics. And Kastrup has got considerable practical experience in physics — Wayfarer

Sure, but there is no like established consensus or even empirical accessibility on these issues where you could appeal to an expert's opinion on "realism" in QM as reliable or unimpeachable. All the experts have different opinions in this field. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kDo you have a reference or an argument for your 'fundamental matter/ energy' claim? — Janus

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kDo you have a reference or an argument for your 'fundamental matter/ energy' claim? — Janus

You mean the claim of infinite regress? The evidence is experiential. Every proposed fundamental particle has been broken down into further particles in experimentation, implying infinite regress. -

Janus

18kEvery proposed fundamental particle has been broken down into further particles in experimentation, implying infinite regress. — Metaphysician Undercover

Janus

18kEvery proposed fundamental particle has been broken down into further particles in experimentation, implying infinite regress. — Metaphysician Undercover

Why would that necessarily be so? For all we know there is nothing more fundamental than quarks. There does seem to be a limit to the possibility of measurement, that much is known. -

Wayfarer

26.2kthere is no like established consensus or even empirical accessibility on these issues where you could appeal to an expert's opinion on "realism" in QM as reliable or unimpeachable. All the experts have different opinions in this field. — Apustimelogist

Wayfarer

26.2kthere is no like established consensus or even empirical accessibility on these issues where you could appeal to an expert's opinion on "realism" in QM as reliable or unimpeachable. All the experts have different opinions in this field. — Apustimelogist

But it’s undeniable that the experts opinions are deeply influenced by their philosophical commitments. Hence Penrose’s insistence that quantum physics is just wrong - because of his unshakeable conviction in scientific realism. Whereas more idealistically-tinged interpretations are compatible with the observations without having to question the theory.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- What is the difference between subjective idealism (e.g. Berkeley) and absolute idealism (e.g. Hegel

- What does this philosophical woody allen movie clip mean? (german idealism)

- Idealism and "group solipsism" (why solipsim could still be the case even if there are other minds)

- Rationalism or Empiricism (or Transcendental Idealism)?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum