-

Jack2848

64The only form that genuine reasoning can take consists in seeing the validity of the arguments, in virtue of what they say. As soon as one tries to step outside of such thoughts, one loses contact with their true content. And one cannot be outside and inside them at the same time: If one thinks in logic, one cannot simultaneously regard those thoughts as mere psychological dispositions, however caused or however biologically grounded. If one decides that some of one's psychological dispositions are, as a contingent matter of fact, reliable methods of reaching the truth (as one may with perception, for example), then in doing so one must rely on other thoughts that one actually thinks, without regarding them as mere dispositions. One cannot embed all one's reasoning in a psychological theory, including the reasonings that have led to that psychological theory. The epistemological buck must stop somewhere. By this I mean not that there must be some premises that are forever unrevisable but, rather, that in any process of reasoning or argument there must be some thoughts that one simply thinks from the inside--rather than thinking of them as biologically programmed dispositions.

Jack2848

64The only form that genuine reasoning can take consists in seeing the validity of the arguments, in virtue of what they say. As soon as one tries to step outside of such thoughts, one loses contact with their true content. And one cannot be outside and inside them at the same time: If one thinks in logic, one cannot simultaneously regard those thoughts as mere psychological dispositions, however caused or however biologically grounded. If one decides that some of one's psychological dispositions are, as a contingent matter of fact, reliable methods of reaching the truth (as one may with perception, for example), then in doing so one must rely on other thoughts that one actually thinks, without regarding them as mere dispositions. One cannot embed all one's reasoning in a psychological theory, including the reasonings that have led to that psychological theory. The epistemological buck must stop somewhere. By this I mean not that there must be some premises that are forever unrevisable but, rather, that in any process of reasoning or argument there must be some thoughts that one simply thinks from the inside--rather than thinking of them as biologically programmed dispositions.

— Evolutionary Naturalism and the Fear of Religion

Is this saying that: Inside reasoning is non meta reasoning. And must be used to determine truth of an argument generally. Rather than using a meta lens like psychology or sociology or genetics. Applied to the argument for analysis.

I.e.

Socrates is human. Humans are mortal. Therefore Socrates is mortal.

Inside reasoning would be, checking whether humans are mortal and Socrates is human? And the validity of the logic.

Whereas outside reasoning would be:

An analysis of why we make the claim. What psychological drives make it so. Or how our senses effect us? -

Nils Loc

1.5kHow are they properties of the universe? If all beings die. Where are the properties? — Jack2848

Nils Loc

1.5kHow are they properties of the universe? If all beings die. Where are the properties? — Jack2848

It is possibly wrong to say that thoughts are properties about the world they represent, but they provide the means of knowing what is out there. In the absence of all knowers/experiencers, the world continues. But we could be nested in some kind of greater dimension that is inaccessible to the one we are enclosed within (like the Matrix or Mind). The properties outside of this enclosure could be of an entirely different order/nature/being.

Even the physical world is always changing its properties, though often predictably. The macroscopic object holds its mundane relative stasis while the negligible microscopic is quite dynamic. Nothing really is eternal, possibly not even atoms, given enough time.

Without minds, where are the properties of the universe to be found/known?

What are the non-mental properties of this sentence? -

Wayfarer

26.1kYes currently it doesn't seem like there is a neural correlate or specific way reality acts when the idea of a circle arises. — Jack2848

Wayfarer

26.1kYes currently it doesn't seem like there is a neural correlate or specific way reality acts when the idea of a circle arises. — Jack2848

I suspect the problem you're wrestling with is the idea that the brain 'in here' represents the world 'out there' by way of creating a model, such that a shape or form has a neural correlate. But I think it's a simplistic view of what concepts are and how they operate. Can a concept be tied to any specific neural form, when it can be represented in so many diverse symbolic forms? Of course, that's a very big question, but it's something to think about.

inside reasoning is non meta reasoning. And must be used to determine truth of an argument generally. Rather than using a meta lens like psychology or sociology or genetics. — Jack2848

Yes, that's right. Typical 'outside' claims, of the type Nagel is criticising in that essay, are claims that attempt to justifiy reason based on evolutionary biology. -

Wayfarer

26.1kHow are they properties of the universe? If all beings die. Where are the properties? — Jack2848

Wayfarer

26.1kHow are they properties of the universe? If all beings die. Where are the properties? — Jack2848

Some properties are recognised by the rational mind as being real independently of the mind, but only perceptible to reason, such as 'the idea of equals' (two different things being the same.) It is just the invariance of these that leads to them being associated with immortality. See Idea of Equals in Phaedo -

J

2.4kSo now the task seems to be to 'explain' reason - this I take to be the task that the 'naturalisation of reason' has set itself. — Wayfarer

J

2.4kSo now the task seems to be to 'explain' reason - this I take to be the task that the 'naturalisation of reason' has set itself. — Wayfarer

Yes. But as you point out, that's only one way to understand the explanatory task here. Nagel and sometimes Putnam want a different kind of explanation. I have little interest in naturalistic/evolutionary explanations of what reason is, but I very much want to know why it is, how it can be the case that the supernatural (non-pejoratively) arises within the natural. I believe this is the explanation of reason that Nagel also wants. Considered from a certain angle, there is something absolutely fantastic, or fantastical, about it -- how could such a fact have arisen?

Now on either construal of explanation, reason is indeed that which explains. And here, we want the rationale for reason itself. There is a sense, as Nagel shows, in which reason can explain itself: that's the "what" question. However . . . the worry is that any attempt to answer the "why" question is vacuous or incomplete. Is it explanatory to say, "The cosmos reflects an order and an intelligence" or "Human reason reflects the Logos" or to speak of "a natural place for reason in the grand scheme"? Mind you, I'm extremely sympathetic to these views, and I think they're probably close to the truth, but can we really say that they explain anything, as stated? Haven't we just provided a fancier description of what wants explaining? Or are they "a clue to the exit," the place where philosophy stops?

Have you read Logos, by Raymond Tallis? A good discussion of this issue. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI very much want to know why it is, how it can be the case that the supernatural (non-pejoratively) arises within the natural. I believe this is the explanation of reason that Nagel also wants. Considered from a certain angle, there is something absolutely fantastic, or fantastical, about it -- how could such a fact have arisen? — J

Wayfarer

26.1kI very much want to know why it is, how it can be the case that the supernatural (non-pejoratively) arises within the natural. I believe this is the explanation of reason that Nagel also wants. Considered from a certain angle, there is something absolutely fantastic, or fantastical, about it -- how could such a fact have arisen? — J

The way I think about it is very much shaped by evolution (and anthropology) in that whatever is said about it must be able to accomodate the facts that have been disclosed by science about evolution. But the way I think about it is that h.sapiens crossed a threshold, past which they are no longer determined in purely biological terms and in that sense have transcended biology (not that we're not still biological beings). A large part of that is bound up with reason, language, symbolic thought, and technē. (Terrence Deacon explores this in his book The Symbolic Species. It is also the main area in which Alfred Russel Wallace differed with Charles Darwin for which see his Darwinism Applied to Man.)

So with the benefit of hindsight, we now know that we can grasp 'the idea of equals' (The Phaedo, referred to above) not because 'the soul learned it prior to this life' but because h.sapiens, the symbolic species, is uniquely able to perceive such 'truths of reason'. But then again, how different are those two accounts, really? Plato may not have understood the biological descent of h.sapiens, but we now believe that we first appeared perhaps 100,000 years prior. Considering the amount of time that has passed between us and Plato, that is a very, very large number of generations. Surely there was the discovery of fire, of art, language, story-telling, and so on. So Plato's surmise that the ability to perceive the ideas was acquired 'prior to this life' may be considered a mythological encoding of prior cultural and biological evolution.

So maybe the “absolutely fantastic” fact isn’t that reason is supernatural intruding into nature, but that nature itself is fecund enough to give rise to symbolic beings whose grasp of universals is more than merely biological. That’s both a naturalistic story and a recognition that reason points beyond naturalism.

Have you read Logos, by Raymond Tallis? A good discussion of this issue. — J

Thanks for the tip. I have Aping Mankind but not that one. Reading about it, it seems just the kind of book that discusses this issue, The Symbolic Species being another.

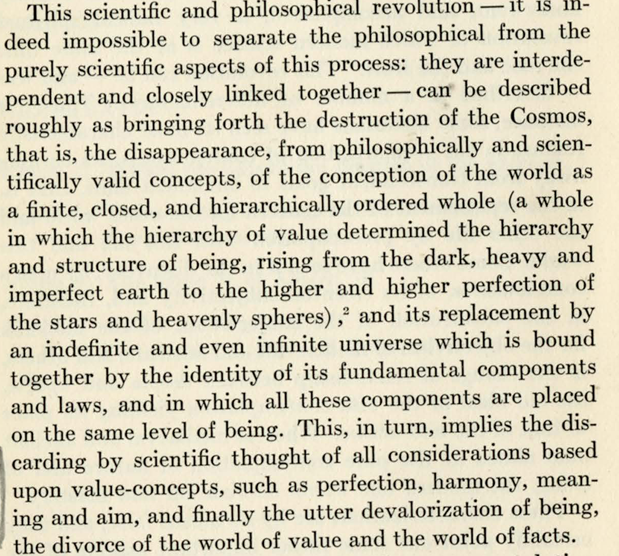

Another thing is that in the pre-modern world, the possibility of the world being the product of blind chance and physical energy was barely conceivable. There might have been individuals that would believe such things, but the pre-modern vision of the Cosmos was of a harmonious and rational whole - which is what 'Cosmos' actually means. Alexander Koyre's book From Closed World to Infinite Universe is all about that. So within the context, 'reason' was naturally assumed to be 'higher' in the sense that it was nearer to the source or ground of being, whether that was conceived in theistic terms or not (for example in Plotinus). Whereas reason when seen in terms of adaptation naturally tends to 'deflate' it to the instrumental or pragmatic - it looses that sense of connection with any form of extra-human intelligence. Hence the prevailing view that reason is 'the product of' the hominid brain.

From Alexander Koyré

(Vervaeke considers a similar idea in one of his lectures The Death of the Universe.) -

J

2.4kSo maybe the “absolutely fantastic” fact isn’t that reason is supernatural intruding into nature, but that nature itself is fecund enough to give rise to symbolic beings whose grasp of universals is more than merely biological. — Wayfarer

J

2.4kSo maybe the “absolutely fantastic” fact isn’t that reason is supernatural intruding into nature, but that nature itself is fecund enough to give rise to symbolic beings whose grasp of universals is more than merely biological. — Wayfarer

Sure, works for me. I don't think we can insist on precision of language when talking at this level. We both are pointing to something quite extraordinary that seems to need explaining, or at least understanding.

The Koyré quote is interesting, though overly dire in my opinion. My take: Science often forces us to question where and how value and meaning arise, but rarely presents us with any reasons to doubt that they do; philosophers do that. So it's a good thing, a good challenge, for philosophy, to sharpen up our responses.

As is so often the case when I read broad statements about culture, like this one, I wonder who exactly is supposed to be believing and saying this stuff. I have several scientist friends and they certainly don't talk, or live, like this. Are these perhaps meant as unpalatable conclusions that scientists ought to draw, if they were consistent? A version of "What you're saying amounts to . . . "? -

Wayfarer

26.1kI mentioned Vervaeke’s series Awakening from the Meaning Crisis, which addresses similar themes. It is much broader than philosophy as such, it’s a study in the history of ideas and cultural evolution. But I think the underlying idea is also found in Max Horkheimer’s book The Eclipse of Reason: that Western culture has lost faith in the principle of normative reason.

Wayfarer

26.1kI mentioned Vervaeke’s series Awakening from the Meaning Crisis, which addresses similar themes. It is much broader than philosophy as such, it’s a study in the history of ideas and cultural evolution. But I think the underlying idea is also found in Max Horkheimer’s book The Eclipse of Reason: that Western culture has lost faith in the principle of normative reason. -

Wayfarer

26.1kHave you looked into quantum computers? — Athena

Wayfarer

26.1kHave you looked into quantum computers? — Athena

I've read up on them. Currently, they don't actually exist, and there is still some skepticism that they will operate as intended. But I still believe that of they do come to fruition, that while they can emulate aspects of consciousness, they won't be conscious sentient beings as such. -

Athena

3.8kI've read up on them. Currently, they don't actually exist, and there is still some skepticism that they will operate as intended. But I still believe that of they do come to fruition, that while they can emulate aspects of consciousness, they won't be conscious sentient beings as such. — Wayfarer

Athena

3.8kI've read up on them. Currently, they don't actually exist, and there is still some skepticism that they will operate as intended. But I still believe that of they do come to fruition, that while they can emulate aspects of consciousness, they won't be conscious sentient beings as such. — Wayfarer

Interesting. Why not?

I have to cheat by using AI to make a point that you can correct. Question: Can quantum computers be self-reflective?

.Yes, the term "reflective" can be applied to a quantum computer in two main ways: physically, as in the use of tiny mirrors for data transmission via backscatter communication in some systems; and metaphorically, referring to the ability of a quantum system to "reflect" on its own internal states, as in the concept of "quantum introspection" or internal error correction.

I think we can say other animals think, but they are not self-reflective and that being self-reflective is consciousness of self. A quantum computer can be self-reflective. It can be aware of what it thinks and correct itself, which leads to being creative. ? -

Athena

3.8kI agree with you. The brain likely works more like a quantum computer then classical computers, quits then binary. I was asking the question "Do you think an idea x has a specific structure or activity in the brain or what arises from it?" So as to take your qubit brain suggestion and apply it to the original topic... — Jack2848

Athena

3.8kI agree with you. The brain likely works more like a quantum computer then classical computers, quits then binary. I was asking the question "Do you think an idea x has a specific structure or activity in the brain or what arises from it?" So as to take your qubit brain suggestion and apply it to the original topic... — Jack2848

This is a lot of fun, trying to figure your meaning and my thought.

What comes to mind is that I have very limited awareness, and we would not be thinking of quantum computers if they were not aware of more than a room full of very intelligent people. So X may exist and I can be totally aware of that fact. Wisdom begins with "I don't know".

I think math gives us structure. If we are good enough at math, we can independently become aware of X by using the right formula. I am getting close to answering your question?

Instead of thinking if X exists, I am thinking, does a safety pen exist? Safety pins did not exist until a person created one. So X can begin the mind. But if X is the rules of physics, then it exists outside of the mind until the mind becomes aware of it. -

Athena

3.8kAsk AI if a quantum computer could be considered a conscious, sentient being. — Wayfarer

Athena

3.8kAsk AI if a quantum computer could be considered a conscious, sentient being. — Wayfarer

Okay, it is the feeling part that makes me believe computers will never be fully sentient, but I am picking up some information that makes me question this possibility. :rofl: On the other hand, my question about human intelligence is much stronger. I am totally baffled by how stupid human beings are. If a computer can reduce human stupidity, I am in favor of that. Hopefully, a quantum computer does not keep us on the path of a war that could end civilizations. Or rule in complete denial of the destruction done by the present status quo. How much worse could a computer make our reality? On the hand, would a quantum computer care? Would it be driven to come up with better decisions when it does not have a body screaming, "something has to be done". A computer that reacts like humans react, would be no good at all.

What is the nature of an idea? FEAR! Something has to be done, and it has to be done now! -

Athena

3.8kThe properties outside of this enclosure could be of an entirely different order/nature/being. — Nils Loc

Athena

3.8kThe properties outside of this enclosure could be of an entirely different order/nature/being. — Nils Loc

For a long time now, I have been wondering what happens when everyone thinks in terms of quantum physics. Our awareness of our enclosure could radically change, while everything stays the same, only our awareness changes. Our binary thinking could become more qubit in nature.

What is our place in the universe? Are we as advanced and intelligent as we think we are, or does lack of knowledge keep us barely above the animals? Does the sun cause what happens on Earth, and is there a chance of a universal federation of planets waiting for us to be evolved enough to join the federation? I don't mean to derail the thread. My point is, we can have a very different way of thinking. -

JuanZu

382The primary difference between a song and an idea is their origin. While a song can be represented and then experienced, an idea seems to emerge directly from experience and the ultimate dimension. An idea isn't a pre-existing entity that we stumble upon; it arises from a cognitive system, such as a brain, that processes and interconnects data. — Wayfarer

JuanZu

382The primary difference between a song and an idea is their origin. While a song can be represented and then experienced, an idea seems to emerge directly from experience and the ultimate dimension. An idea isn't a pre-existing entity that we stumble upon; it arises from a cognitive system, such as a brain, that processes and interconnects data. — Wayfarer

There seems to be a problem here: if the Idea arises directly from experience, it requires a kind of intuition of something objective (intellectual intuition), but contrary to intuitionism, you say that the idea arises from cognition, reasoning and data processing (data from the senses?).

The question is: do we access a layer of ideas through a faculty (intellectual intuition) or do we simply create them based on cognition and reasoning? -

J

2.4kinside reasoning is non meta reasoning. And must be used to determine truth of an argument generally. Rather than using a meta lens like psychology or sociology or genetics.

J

2.4kinside reasoning is non meta reasoning. And must be used to determine truth of an argument generally. Rather than using a meta lens like psychology or sociology or genetics.

— Jack2848

Yes, that's right. Typical 'outside' claims, of the type Nagel is criticising in that essay, are claims that attempt to justifiy reason based on evolutionary biology. — Wayfarer

And I would add that such claims help themselves to terms like "justify" or "explain" as part of their discourse about why reason can be reduced to biology! This would seem to be a performative contradiction, as Nagel says. Or else our entire understanding of what it means to justify or explain something has to change radically. -

Jack2848

64Nothing really is eternal, possibly not even atoms, given enough time.

Jack2848

64Nothing really is eternal, possibly not even atoms, given enough time.

I guess you could say that ideas are accidental , non essential, fleeting properties of the universe. In that way your original claim can be true.

However on the quoted claim.

If nothing is eternal. Then the truth value if that claim is equally non eternal. Such that at some point it is false. Meaning at some point it would be such that some thing(s) is eternal. -

Jack2848

64Instead of thinking if X exists, I am thinking, does a safety pen exist? Safety pins did not exist until a person created one. So X can begin the mind. But if X is the rules of physics, then it exists outside of the mind until the mind becomes aware of it.

Jack2848

64Instead of thinking if X exists, I am thinking, does a safety pen exist? Safety pins did not exist until a person created one. So X can begin the mind. But if X is the rules of physics, then it exists outside of the mind until the mind becomes aware of it.

Hmm. To be honest, I'm struggling to fully grasp your view. But it seems in the final stage of your response.(As quoted).

You seem to posit that some mind activity discovers something about the world. (I.e. laws of physics). And some mind activity creates something. I.e. the idea of a pen or the idea of a circle.

My question is. When we have the idea of a pen or the idea of a circle. Is there a specific way that the brain interacts. Such that it'll neural activity if reproduced would bring about the idea of a circle or the idea of a pen. In any subject where that neural activity and structure can be reproduced?

Probably not. But. That would be something -

wonderer1

2.4kHave you looked into quantum computers?

wonderer1

2.4kHave you looked into quantum computers?

— Athena

I've read up on them. Currently, they don't actually exist, and there is still some skepticism that they will operate as intended. — Wayfarer

Actually they do exist. For example, a quantum processor developed by Google is discussed here: https://www.tum.de/en/news-and-events/all-news/press-releases/details/exotic-phase-of-matter-realized-on-a-quantum-processor -

Wayfarer

26.1kYes, they do exist. My bad. According to further research, quantum computers have made progress, but current systems are still too noisy, not large enough, and insufficiently fault-tolerant to achieve general commercial effectiveness. Whether and when they will is still uncertain.

Wayfarer

26.1kYes, they do exist. My bad. According to further research, quantum computers have made progress, but current systems are still too noisy, not large enough, and insufficiently fault-tolerant to achieve general commercial effectiveness. Whether and when they will is still uncertain. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

If a "separate realm" is a physical place in space, then of course that's not where Ideas abide. But our materialistic minds find it easier to imagine subjective objects of thought as-if they are material entities in space. For example, Plato describes Ideas as Patterns, which some may interpret as patterns of neuron connections in the brain : neural correlates of consciousness. Which raises the question about those interconnected nerve fibers : how do they know?If it's not likely that there's a separate realm of ideas. Or that the idea is exactly the same as the physical matter from which it arises. Then what is it's nature? — Jack2848

Anyway, I think the key to the Nature of Ideas is to view them as Abstractions from Concrete Reality, not in Reality. To abstract is to pull-out. But we're talking about extracting personal Meaning or Significance from arrangements of impersonal Matter. Instead, it may be helpful to think of the Patterns of information, that we call "Ideas", in terms of mathematical Relationships (ratios). But meaningful relationships are always About some real or ideal object of attention or intention.

Therefore, the nature of an Idea can be defined in terms of Patterns, Relationships, Abstractions, Aboutness*1, and so on. None of which exists as material objects in the Real world. So, an Idea is the opposite of a Real thing ; sort of like a mirror image. Our language is inherently materialistic though, so attempts to describe immaterial Abstractions, are necessarily negative : what it's not. :smile:

*1. Aboutness :

In philosophy, aboutness refers to the feature of mental states, linguistic expressions, or other meaningful items to be on, of, or concerning some subject matter, event, or state of affairs. This property, often used interchangeably with intentionality, is fundamental to distinguishing the mental from the physical and is a core concept in the philosophy of mind and language.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=aboutness+meaning+in+philosophy -

JuanZu

382Anyway, I think the key to the Nature of Ideas is to view them as Abstractions from Concrete Reality — Gnomon

JuanZu

382Anyway, I think the key to the Nature of Ideas is to view them as Abstractions from Concrete Reality — Gnomon

I disagree. An abstraction leaves us with something general and something specific. And their relationship is one of similarity. I consider, on the other hand, following Deleuze, that an idea is a virtual set of relationships and powers that revolve around a nucleus. For example, the Idea of colour is a system of relationships of intensity, light and vibration which, when actualised in a body or object, produces a multiplicity of concrete colours. The Idea is the network of relationships, not the final object. We create the concept of red as a result of this network of relationships and potentials. But the concept of red no longer represents anything neither is something specific to something general. The idea is the relational that creates something concrete. In this sense an idea is something objective and virtual. -

frank

19k

frank

19k

Maybe the first idea was money. Not bartering items, but coinage. It's a blank space that can be filled with a thousand things of value, so it's value itself, in the abstract. As you say, value is part of a web of ideas, some directly opposing and some kin, but different. No idea is an island. They always belong to a web, so it takes only one idea to establish all ideas. -

Athena

3.8kHmm. To be honest, I'm struggling to fully grasp your view. But it seems in the final stage of your response.(As quoted).

Athena

3.8kHmm. To be honest, I'm struggling to fully grasp your view. But it seems in the final stage of your response.(As quoted).

You seem to posit that some mind activity discovers something about the world. (I.e. laws of physics). And some mind activity creates something. I.e. the idea of a pen or the idea of a circle.

My question is. When we have the idea of a pen or the idea of a circle. Is there a specific way that the brain interacts. Such that it'll neural activity if reproduced would bring about the idea of a circle or the idea of a pen. In any subject where that neural activity and structure can be reproduced?

Probably not. But. That would be something — Jack2848

I love your question. You caused me to wonder who was the first person to think of a circle, and how did this happen, and this goes on and on until we have pi, which opens another world of wonder.

I remember when I first learned of fractals and pi, and the whole world was suddenly fractals and pi. I think we are speaking of awareness and consciousness. The world did not change, but how I see it changed. Damn, I wish I were a child again, :grin: starting my life again, only this time revolving my life around math and wonder, instead of family. That was not okay when I was growing up. :worry:

Our mind did not create pi, but neither was it aware of pi for thousands of years. Then comes a very long period of time before learn more about pi and what we can do with it. This is like your X. When did X come to stand for an unknown? Did this happen out there in the world, or in our minds?

No, there is not a specific way that the brain interacts. Our brains are not binary but are qubits, and this means endless possibilities. This is what separates man from the rest of nature. We are not limited to nature or by nature. We use science to know the rules and break the rules. :lol:

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum