-

Streetlight

9.1kIn a famous line from D'Arcy Thompson's On Growth and Form, Thompson refers to the body as a 'diagram of forces'. This is a particularly evocative phrase, but one whose meaning is best displayed pictorially:

Streetlight

9.1kIn a famous line from D'Arcy Thompson's On Growth and Form, Thompson refers to the body as a 'diagram of forces'. This is a particularly evocative phrase, but one whose meaning is best displayed pictorially:

On the right is a thigh bone (femur) while on the right is a crane head - the lines indicate 'stress contours', or vectors of tension and compression. Thompson relays the story of how one day, an colleague of his, an engineer, happened to walk past the drawing of the femur, pinned to the wall of an anatomists's board, and, with the shock of recognition exclaimed: 'that's my crane!'. Like the crane, the bone's morphology (form and shape) exhibited nothing less than the play of forces which shaped it, and moreover, which made the bone perfectly suited to it's task of load-bearing. It's with examples like this in mind, along with numerous others, which lead Thompson to claim that the body is nothing other than a 'diagram of forces'.

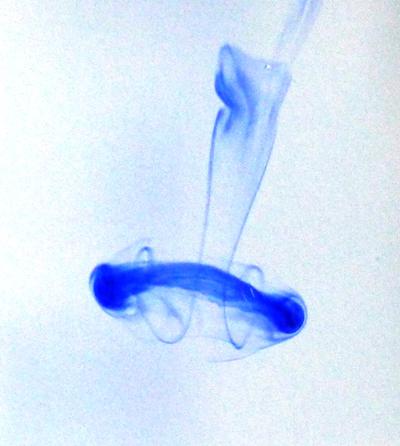

Philosophically, I think is an incredibly powerful and interesting way of thinking about bodies, insofar as it takes the focus away from bodies as, well, static lumps of meat and bone, and instead frames the body as a dynamic outcome of environment and action, placing it into a milieu which works upon it over time, dynamising and temporalizing the body as less a thing than a process, always ongoing. To make the point even clearer, and to speak of whole bodies rather than just parts, one might take the striking example of ink drops in water:

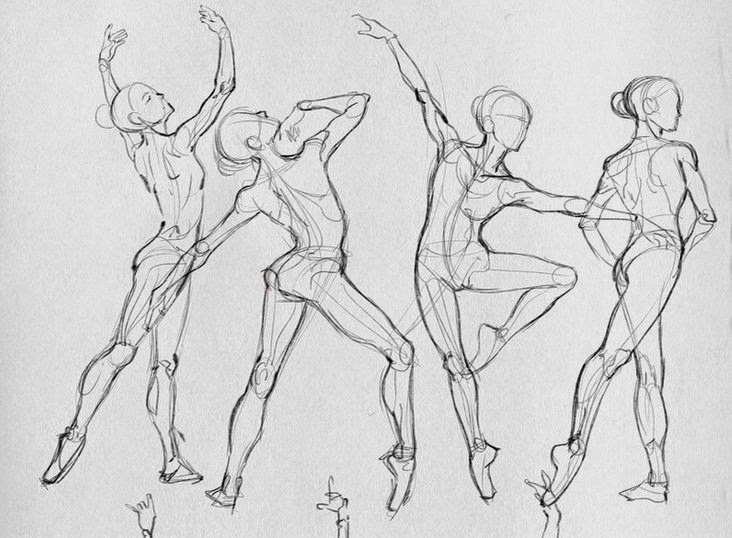

It is mere coincidence that the ink drops look so much like the forms of jellyfish? While this latter example is more speculative than the first, one can at least see in them the same principles at work in the crane and the bone: the coupling of form and movement, process and embodiment. But more than just in natural terms, one can even see this play out in what is probably one of my favourite works of art, Umberto Boccioni's Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, which I had the pleasure of seeing in the flesh a couple of years back:

Boccioni was an Italian Futurist, who, like all Futurists, was concerned above all with speed and flux, principles which largely informed their approach to art. What's so cool about the sculpture is that it aims less at capturing a 'body' than a stride, a form-of-motion, motion given form, and not simply a body that so-happens to move. Movement is primary, even as the depiction itself is static (statuesque?!). The title of the piece - Unique Forms of Continuity in Space - also emphasises this, the continuity of body with space. In any case, what all the above illustrate are ways of thinking the body as a 'diagram of forces'. Like Boccioni's sculpture, diagrams are interesting because they always 'point elsewhere'; they capture, in static form, dynamics: one sees in diagrams movement(s), lines of force, directions, orientations. And bodies are always best, I think, thought of in exactly those terms.

-

Streetlight

9.1kRodin's The Kiss is probably another, awesome example of bodies as shaped by forces, although perhaps one can speak here of amorous forces, eroticism articulated in the bend of elbows and twist of torsos:

Streetlight

9.1kRodin's The Kiss is probably another, awesome example of bodies as shaped by forces, although perhaps one can speak here of amorous forces, eroticism articulated in the bend of elbows and twist of torsos:

-

Streetlight

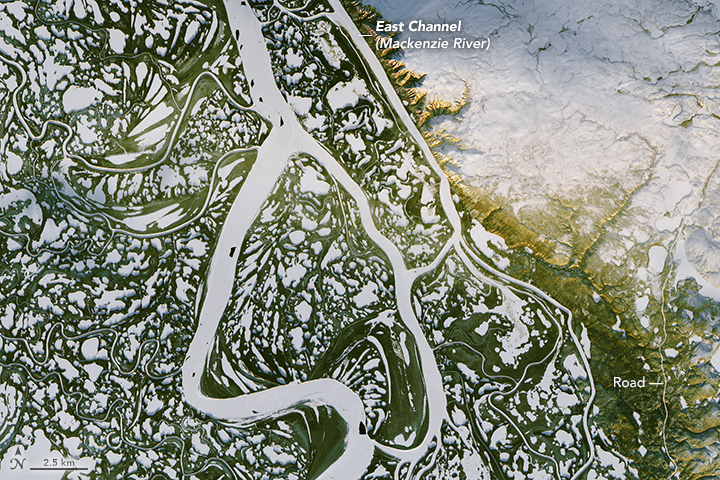

9.1kOne can - and should - also see inorganic, macroscopic bodies as diagrams of forces too: bodies of water as diagrams of water flows:

Streetlight

9.1kOne can - and should - also see inorganic, macroscopic bodies as diagrams of forces too: bodies of water as diagrams of water flows:

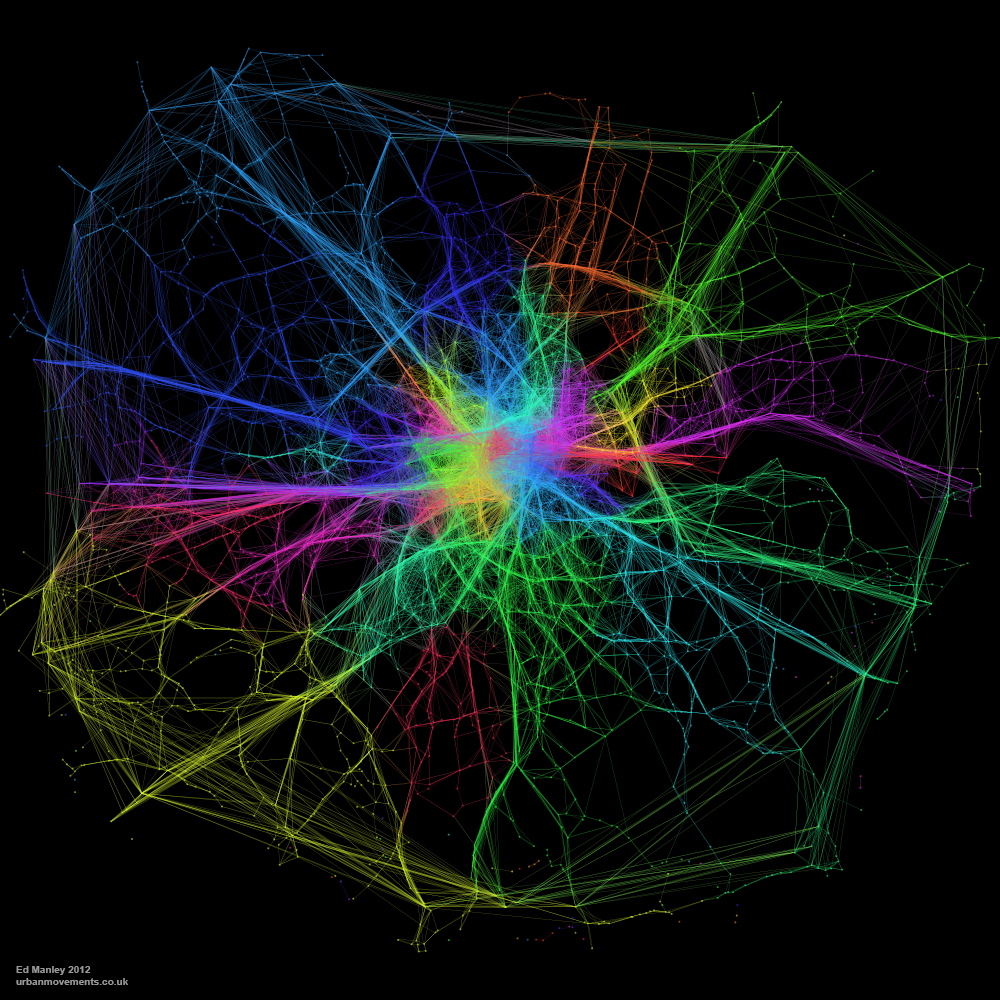

Bodies of cities as diagrams of population flows:

(data visualisation of traffic flows in London)

Airflows across an F-18:

All more examples of bodies - broadly construed - as diagrams of forces. Another way to put this of course is that all of these things are ecosystems... -

apokrisis

7.8kAgain that is half the story - the dynamical bit. The other half is the informational bit - the regulation or semiosis that switches logarithmic growth processes off and on.

apokrisis

7.8kAgain that is half the story - the dynamical bit. The other half is the informational bit - the regulation or semiosis that switches logarithmic growth processes off and on.

That was one of the points about effective field theories. They model a hierarchical or fractal development of scale - the bit that renormalisation describes as a homogenous ground state. Yet - rather artificially - limits must be inserted to prevent infinities that would blow things up. Some kind of "regulator" - like the imposition of a lattice, fractional dimensions or mass cancelling particles - has to be added to the ontology.

So nature is growth plus switches. Bodies are formed by dynamical and self-organising growth processes. But genes need to provide the schedule that knows when to turn the growth on and when to turn it off. -

charleton

1.2kIt is mere coincidence that the ink drops look so much like the forms of jellyfish? — StreetlightX

charleton

1.2kIt is mere coincidence that the ink drops look so much like the forms of jellyfish? — StreetlightX

Everything looks like something else when you are a pattern seeking animal. Ink drops fall, and by the reverse effort a jellyfish propels itself upwards. But there are other ways to do this. -

T Clark

16.1kOn the right is a thigh bone (femur) while on the right is a crane head — StreetlightX

T Clark

16.1kOn the right is a thigh bone (femur) while on the right is a crane head — StreetlightX

By the way, what is a "crane-head?" Doesn't look like a part to any crane I've ever seen, machine or bird. -

Streetlight

9.1k

Streetlight

9.1k

It's the head of a fairbairn crane:

Also, thanks for the force diagrams but the most pertinant point is not to see forces diagrammed in the abstract (as 'graphs') but to see bodies themselves as directly diagamming forces. Bodies are diagramms (of forces). -

Streetlight

9.1kAlso worth noting that the femur, with it's cross-hatched pattern of stresslines, was also (one of the) inspirations for the Eiffel tower, in what counts as one of the coolest applications of biomimetics I know:

Streetlight

9.1kAlso worth noting that the femur, with it's cross-hatched pattern of stresslines, was also (one of the) inspirations for the Eiffel tower, in what counts as one of the coolest applications of biomimetics I know:

https://www.wired.com/2015/03/empzeal-eiffel-tower/

"The Eiffel tower is incredibly well optimised to do what it was designed to do, to stand tall and stand strong, while using a minimum of material. Rather than hide its inner workings with a facade, Eiffel exposed the skeleton of his masterpiece. In doing so, he revealed its "hidden rules of harmony", many of the same rules that give your skeleton its lightweight strength." -

T Clark

16.1kAlso, thanks for the force diagrams but the most pertinant point is not to see forces diagrammed in the abstract (as 'graphs') but to see bodies themselves as directly diagamming forces. Bodies are diagramms (of forces). — StreetlightX

T Clark

16.1kAlso, thanks for the force diagrams but the most pertinant point is not to see forces diagrammed in the abstract (as 'graphs') but to see bodies themselves as directly diagamming forces. Bodies are diagramms (of forces). — StreetlightX

I understand, but what took me some time to recognize in school, is the way forces move through the element as a function of position rather than time. That's what struck me as similar. A Mohr's circle or shear moment diagram presents all the views of forces in the elements at one time. A single view of everything that's going on in three dimensions. -

Streetlight

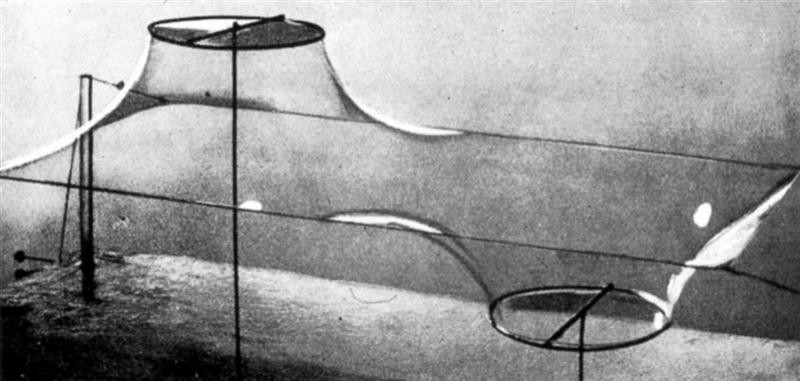

9.1kThis also feeding into some of the Frei Otto's structure's that I posted in the Beautiful Structures Thread. You can see below how Otto translated his experiments with bubbles and surface tension to create his German Pavilion:

Streetlight

9.1kThis also feeding into some of the Frei Otto's structure's that I posted in the Beautiful Structures Thread. You can see below how Otto translated his experiments with bubbles and surface tension to create his German Pavilion:

Like everything else here, Otto's structures are force diagrams. The sculptor Tobias Putrih creates bubble sculptures inspired by Otto's work:

-

Streetlight

9.1kI understand, but what took me some time to recognize in school, is the way forces move through the element as a function of position rather than time. That's what struck me as similar. A Mohr's circle or shear moment diagram presents all the views of forces in the elements at one time. A single view of everything that's going on in three dimensions. — T Clark

Streetlight

9.1kI understand, but what took me some time to recognize in school, is the way forces move through the element as a function of position rather than time. That's what struck me as similar. A Mohr's circle or shear moment diagram presents all the views of forces in the elements at one time. A single view of everything that's going on in three dimensions. — T Clark

Ah, I see what you mean. I suppose what I 'don't like' about such diagrams is precisely that the abstract away the time element, and correlatively, the body. One way to think about this is that embodiment always entails an 'entemporalment': to have a body is to exist in time (which is why Plato - as Nietzsche put it - was a 'despiser of the body', and much preferred eternity to time - these two things are not unrelated). Trying to insist on the irreducible 'forceful' nature of time (and space) is something I tried to explore in my other recent thread on time and space. -

Galuchat

809Ah, I see what you mean. I suppose what I 'don't like' about such diagrams is precisely that the[y] abstract away the time element, and correlatively, the body. — StreetlightX

Galuchat

809Ah, I see what you mean. I suppose what I 'don't like' about such diagrams is precisely that the[y] abstract away the time element, and correlatively, the body. — StreetlightX

The beams represented by shear and moment diagrams are actual bodies supporting actual loads (sustaining forces) in static equillibrium, hence; the time element is irrelevant. However, the space (geometry) element is not.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- If I knew the cellular & electrical activity of every cell in the brain, would the mind-body problem

- Can a computer think? Artificial Intelligence and the mind-body problem

- How can Christ be conceived as God while possesing a human body and being present for a time in Hell

- Monozygotic Twins and Mind-Body Dualism

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum