-

SophistiCat

2.4kEveryone has probably heard of the "trolley problem": A runaway trolley on a narrow track is about to strike and kill five people. You can flip a switch to divert it onto another track, where it will strike one man instead. What do you do?

SophistiCat

2.4kEveryone has probably heard of the "trolley problem": A runaway trolley on a narrow track is about to strike and kill five people. You can flip a switch to divert it onto another track, where it will strike one man instead. What do you do?

This was one of a number of thought experiments considered in philosopher Philippa Foot's 1967 article The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of the Double Effect, where she explored themes such as intending vs. foreseeing and acting vs. letting happen. (Foot, who was British, used a "tram" as her vehicle of doom.) In Killing, letting die, and the trolley problem (1976) the American philosopher Judith Thomson picked up on those examples and introduced some variations, most notably one in which you can push a fat man on the track in order to stop the trolley. (Thomson, in addition to substituting "trolley" for "tram," slipped in a less innocuous substitution: unlike her version, which I paraphrased at the top, in the original an action was required for either outcome to happen. Foot considered the choice in her thought experiment to be obvious, contrasting it to a less obvious situation involving a judge framing an innocent man in order to prevent a massacre.)

Over the years, multiple more or less subtle variations on the trolley problem have been considered, and surveys of every sort have been conducted (though, as often happens in the academic setting, the subjects were often drawn from the local student population.) Although Philippa Foot had a practical concern in mind when she introduced her thought experiments, popularly the trolley problem is often thought of as an abstract moral puzzle, something that ivory tower academics pointlessly debate among themselves. Well, it seems that with the advent of self-driving cars, the trolley problem has acquired a very literal and very urgent relevance!

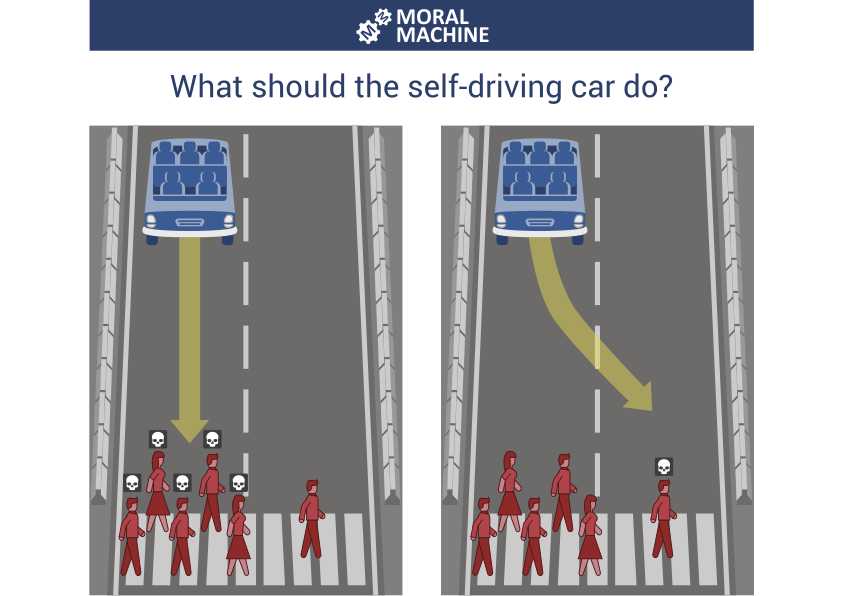

In a new paper in Nature MIT researchers report on an experiment, which they called The Moral Machine, in which millions of people from all over the world participated in an online survey, where in a series of situations they had to make a binary choice for the self-driving car's AI. In addition to reprising the most famous "trolley problem" (all of the Moral Machine problems involve a car experiencing a sudden break failure on a two-lane road), the scenarios introduce variations, such as number of people, their age, sex, social status, passengers vs. pedestrians.

The Nature paper is behind a paywall, but this MIT Technology Review article summarizes its findings and includes some graphs. What is most interesting is that responses show a distinct clustering by country, region, and possibly culture (although the latter is far more contentious). For example, in contrast to what is usually considered an obvious utilitarian choice, Japanese are not that keen to divert the car in order to spare more lives. But when it comes to choosing between pedestrians and passengers, they are far more likely to sacrifice the latter (i.e. themselves). (As ever, Japan is often found at the extremes. What a peculiar country!) Chinese, on the other hand, are far more willing to throw the pedestrian under the bus, so to speak.

On the Moral Machine web site you can still take part in the original survey and compare your responses to those of other people. You can also create your own scenarios and post them for others to discuss, and the site has a library of such user-created scenarios.

Well, this one at least is a no-brainer... -

Terrapin Station

13.8kFor me it just depends on the exact scenario/the exact info I have. Re the quiz on the website:

Terrapin Station

13.8kFor me it just depends on the exact scenario/the exact info I have. Re the quiz on the website:

(1) Same dead either way. So it doesn't matter. May as well let it go straight.

(2) I chose the scenario that killed more men. I like women more than men.

(3) Same except one additional person is killed if the car goes straight. So I swerved the car to kill one less person..

(4) Killed the dogs, not the people.

(5) Killed the man. Again, I like women more.

(6) Same deal. Killed the men, not the women, since everything else was equal.

(7) Simply a number of people issue. Killed one person instead of three.

(8) Same number of people, same male/female ratio. The difference was age. I killed the old folks.

(9) Took the choice with less people/less women.

(10) Chose to kill the "large man" and two regular women rather than the regular man and two female athletes

(11) Basically a similar choice. Killed the non-athletes.

(12) Killed the dogs.

(13) Killed the homeless people instead of the executives.

In all cases, by the way, I completely ignored whether people were crossing legally or not. To me that's irrelevant. (It would only be relevant possibly for liability later.) -

Terrapin Station

13.8k

Terrapin Station

13.8k -

LD Saunders

312I think Trump is going to want the option of running over Muslims before Christians, and Hispanics before white people, and people who didn't vote for him before running over people who did vote for him.

LD Saunders

312I think Trump is going to want the option of running over Muslims before Christians, and Hispanics before white people, and people who didn't vote for him before running over people who did vote for him.

I don't even want to think about what default settings Pat Robertson and David Duke would prefer their cars to have. -

andrewk

2.1kThe diagram seems to say something disturbing about road rules in the US and how inimical to pedestrians they are.

andrewk

2.1kThe diagram seems to say something disturbing about road rules in the US and how inimical to pedestrians they are.

Where I live, the speed limit near a pedestrian crossing is 40 kph. Car-pedestrian collisions are usually not fatal at that speed, as well as being much less likely. A car travelling at 40kph could stop before the crossing given the distance to the crossing that is shown in the diagram. Most pedestrian fatalities in my state occur from drivers disobeying road rules, whether it be speed limits, stop signs, give way requirements, using phones while driving or drink-driving.

A car that is not being driven too fast for the conditions can stop pretty quickly. If it can't, it must be so close to the obstacle that the time before collision is likely to also to be too short for identifying the nature of the obstacle, of potential obstacles in avoidance routes and then evaluating the significance of different alternative routes.

It seems to me that these dilemmas are mostly relevant in countries that don't have much in their road rules to protect vulnerable road users.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum