-

Andrew4Handel

2.5kI think that there are two notions needed for the existence of property. One is scarcity and the other is justification.

Andrew4Handel

2.5kI think that there are two notions needed for the existence of property. One is scarcity and the other is justification.

With scarcity, for example, if there were a few humans and lots of land we wouldn't need the concept of property because there would be excess resources that no one one person could dominate or need.

The notion of justification is the the idea that someone has earned or justified claiming something as their property.

It seems property can only be maintained by force where a society and its military and police and government defend an individuals property claim. But beyond that I don't see any metaphysical type of ownership justified by someones innate right to an object.

I think one problem is how the first society or individual managed to gain the first property or land before it was distributed via a legal system. Personally, I don't believe I own anything and I am happy for anyone to share my property if they need it and I consider myself as a steward borrowing and caring for resources that may be inherited by someone else. -

Andrew4Handel

2.5kI think there is a problem that we have a very complex system of of ownership and financial value which I don't think is justified which I would now compare to a complex religious system which can be effective but is not based on truth.

Andrew4Handel

2.5kI think there is a problem that we have a very complex system of of ownership and financial value which I don't think is justified which I would now compare to a complex religious system which can be effective but is not based on truth. -

Ciceronianus

3.1kFor the concept of "property" to exist, the only thing required is law, if by "property" you mean something which a person can claim to own.

Ciceronianus

3.1kFor the concept of "property" to exist, the only thing required is law, if by "property" you mean something which a person can claim to own. -

Andrew4Handel

2.5k

Andrew4Handel

2.5k

I don't think "Property" and "own" are necessarily meaningful.

For example can you own something once you are dead? In this sense owning something does not attach you to the thing in an compelling way.

Also you can "own" a car but it can been taken by someone and you may never a see it again.

The legal status of property seems to mean that law enforcers will defend something that is claimed to belong to you. But I don't think the law is a compelling force and we can just agree to disagree with it. It is somewhat arbitrary and partly due to social agreements.

One issue raised about limits to ownership is whether you can do anything you like to something you are considered to own. But there are often restrictions here such as you cannot modify a historic listed building or burn down your house. I think this highlights a problem with the concept of ownership where it leads to exploitation and not stewardship of a precious resource. The law fluctuates on these issues. -

Outlander

3.2kSomeone who say I don't know cured cancer or saved a monastery of devout monks from barbarians deserves a place to lay his heroic head. And perhaps his kid should as well. And theirs. And maybe even so on. However somewhere down the line, even after a long while. The great, great, great, great (continue this as long as you please) grandkid eventually just does nothing and turns into a degenerate sociopath... and say along the opposing line one of the former barbarians ends up being a wonderful person and even shining beacon of decency... eh. Up for the people to decide it would seem. Let's hope they do so properly.

Outlander

3.2kSomeone who say I don't know cured cancer or saved a monastery of devout monks from barbarians deserves a place to lay his heroic head. And perhaps his kid should as well. And theirs. And maybe even so on. However somewhere down the line, even after a long while. The great, great, great, great (continue this as long as you please) grandkid eventually just does nothing and turns into a degenerate sociopath... and say along the opposing line one of the former barbarians ends up being a wonderful person and even shining beacon of decency... eh. Up for the people to decide it would seem. Let's hope they do so properly. -

Ciceronianus

3.1kFor example can you own something once you are dead? In this sense owning something does not attach you to the thing in an compelling way. — Andrew4Handel

Ciceronianus

3.1kFor example can you own something once you are dead? In this sense owning something does not attach you to the thing in an compelling way. — Andrew4Handel

Well, you can't do much of anything when you're dead. However, you can, now, impose restrictions on the use of property which will govern its use after you're dead, through a will or a trust.

Anyone may steal a car or otherwise violate the law applicable to property of persons. This merely impacts possession of property. The property may be obtained through the courts, and the violators may be arrested and prosecuted if the violation is criminal, and be punished.

You may disagree with the law all you like. But there is nothing else which will define property and establish rules governing it, which may be enforced by any authority. -

Andrew4Handel

2.5kYou may disagree with the law all you like. But there is nothing else which will define property and establish rules governing it, which may be enforced by any authority. — Ciceronianus the White

Andrew4Handel

2.5kYou may disagree with the law all you like. But there is nothing else which will define property and establish rules governing it, which may be enforced by any authority. — Ciceronianus the White

I don't think the law justifies property. To me it just seems that the law allows use of force to dominate a thing. And the law can act in the same manner as a "thief" using force to take something.

But the law often cannot resolve ownership disputes and different countries and different groups are in a state of perpetual conflict over resource and rights.

I think we should rely on a notion of stewardship as opposed to just accumulating wealth, exploiting resources and owning things. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

Until now we’ve justified it with the concept of rights, in this case the right that the worker has to the value he has created by his own labor. Man must sustain his life through his own efforts, and if he cannot use the product of his own effort as he sees fit, he cannot sustain his life. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

For the concept of "property" to exist, the only thing required is law, if by "property" you mean something which a person can claim to own.

It’s the other way about. Without property there would be no laws protecting it. -

Echarmion

2.7kIt seems property can only be maintained by force where a society and its military and police and government defend an individuals property claim. But beyond that I don't see any metaphysical type of ownership justified by someones innate right to an object.

Echarmion

2.7kIt seems property can only be maintained by force where a society and its military and police and government defend an individuals property claim. But beyond that I don't see any metaphysical type of ownership justified by someones innate right to an object.

I think one problem is how the first society or individual managed to gain the first property or land before it was distributed via a legal system. Personally, I don't believe I own anything and I am happy for anyone to share my property if they need it and I consider myself as a steward borrowing and caring for resources that may be inherited by someone else. — Andrew4Handel

Based on what I know about the history of early humanity and the development of human children it seems likely that some form of limited personal property is common to human societies and is present in hunter-gatherer band-level societies. This only extends to personal tools and clothing. From a practical perspective, it also seems to make sense to assign to each person some basic necessities as their own personal responsibility to avoid excessive bookkeeping.

But what if two bands want to trade goods? There is some evidence that happened even very early in the history of anatomically modern humans. Trading goods requires (or perhaps creates) at least the tacit acknowledgment that whatever is being traded belongs to either band.

I think it's generally accepted that "real property", that is ownership of land, only enters the picture once agriculture has developed (though some general notion of "territory" may well have been around), and that ownership of land - which to an agricultural society is mostly equivalent to ownership over the means of production - was communal.

I can think of two reasons a communal ownership of land is preferrable to having no ownership: If the land is considered the property of the society, that establishes certain obligations on the individual to treat the land in accordance with the interests of that society. And by that same token it serves to delineate the borders of the society and those responsibilities.

So I think those are the core elements: Establishing and delineating responsibility and organizing the commerce of goods. As society grows more complex, the demands for that also grow. As soon as people are wholly employed in a function that doesn't either serve their basic needs, or ensures they're met due to social status, i.e. artisans, they're in need of more robust forms of private property.

That's only a very brief look at the topic, but to jump far ahead to the modern day: I think market-based distribution is an effective way to organise many (but not all) social relationships. This form of organisation requires property to function, and insofar as property is necessary for a justified form of distribution, it is itself justified. -

Pfhorrest

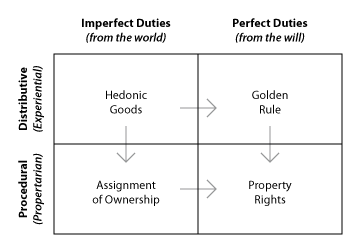

4.6kProperty is important because it’s inextricably tied up with more basic concepts like rights and procedural justice.

Pfhorrest

4.6kProperty is important because it’s inextricably tied up with more basic concepts like rights and procedural justice.

Procedural justice is about adherence to strict, transactional, rules of behavior, or procedures, while distributive justice is about how value ends up distributed among people as a consequence of whatever behavior. I hold that distinction to be analogous to the epistemological distinction between analytic and synthetic knowledge. Both procedural justice and analytic knowledge are simply about following the correct steps in sequence from a given starting point to whatever conclusion they may imply, analytic knowledge following just from the assigned meaning of words and procedural justice following just from the assigned rights that who has over what (which I analyze as identical to the concept of ownership, i.e. to have rights over something is what it means to own it). Likewise both distributive justice and synthetic knowledge are about the the experience of the world, synthetic knowledge about the sensory or descriptive experience of the world and distributive justice about the appetitive or prescriptive experience of the world.

Meanwhile the distinction between perfect and imperfect duties, which was introduced by Immanuel Kant, is roughly the distinction between specific things that we are obliged to always do, and general ends that we ought to strive for but admit of multiple possible means of realization. I reckon that distinction, in turn, to be analogous to the epistemological distinction between a priori and a posteriori knowledge, because just as a priori knowledge comes directly from within one's own mind (concerning the kinds of things that can coherently be believed) while a posteriori knowledge comes from the outside world, so too perfect duties come directly from within one's own will (concerning the kinds of things that can coherently be intended) while imperfect duties comes from the outside world.

Many liberal or libertarian political philosophers have at least tacitly treated these distinctions as largely synonymous, with procedural justice, matters concerning the direct actions of people upon each other and their property, being the only things about which anyone has any perfect duties, on their accounts; and conversely, distributive justice, matters concerning who receives what value in the end, being at most subject to imperfect duties, if even that. But I argue that, just as Immanuel Kant showed that the distinction between analytic and synthetic knowledge was orthogonal to the distinction beween a priori and a posteriori knowledge, so too the distinction between procedural and distributive justice is orthogonal to the distinction between perfect and imperfect duties.

At the intersection of matters of distributive justice and perfect duties lies the moral analogue of the synthetic a priori knowledge that Kant introduced. While that synthetic a priori knowledge is about imagining hypothetical things in the mind and exploring what sorts of things could even conceivably be imagined to be, this intersection of perfect duty and distributive justice is where I place the traditional moral concept of "The Golden Rule": if you cannot imagine it seeming acceptable to you for someone else to treat you some way, then you must find it morally unacceptable to treat anyone else that way.

This is very similar to but subtly distinct from the matter of property rights — of not acting upon something contrary to the will of its owner (including a person's body, which they necessarily own, i.e. necessarily have rights over), which lies in the traditional intersection of perfect duties and procedural justice — because it does not rely on any assignment of ownership, but only on experiential introspection; in much the same way that synthetic a priori knowledge is very similar to but subtly different from analytic a priori knowledge, in that it does not rely on any assignment of meaning to words, but only, again, on experiential introspection.

And of course, just as I hold there to be a category of analytic a posteriori knowledge as well, I also hold there to also be an intersection of procedural justice and imperfect duties as well, which is of utmost importance. For while distributive perfect duties are obligatory (as obligation tracks with perfect duty, and omissibility with imperfect duty), for that same reason of them being internal to the will (hence perfect duties), but not in terms of publicly established relationships of rights (hence distributive), they are not interpersonally relatable, and so are only a matter of private justice, not public society. The only obligations that can be treated publicly are those phrased in terms of property with assigned ownership, procedural perfect duties; but those in turn depend on the procedural imperfect (and thus omissible) duties of assignment of such ownership.

When we assign ownership of certain things to certain people, which is to say that the will of those people controls what it is permissible to do to or with those things, we get procedural matters of perfect duty, where we no longer need to actually do the imagining of what it would feel like to be another person being acted upon in some way, and can just deal in abstract claims. This is where we enter the realm of property rights, things that are right or wrong just in virtue of who owns what and what they do or don't want done with it, regardless of whether it actually inflicts hedonic suffering or not.

But this kind of justice in turn depends on another kind of imperfect duty, just as distributive perfect duties depend on distributive imperfect duties. Procedural perfect duty, justice in virtue of who owns what, depends on the assignment of ownership of the things in question, and that is not something that is itself a matter of perfect duty, but only imperfect duty. Nobody inherently owns anything but themselves; rather, sociopolitical communities arbitrarily assign ownership of property to people, and could assign it differently. People own what other people agree that they own, and so long as everyone involved agrees on who owns what, that is all that is necessary for that ownership to be legitimate, to conform to the procedural imperfect duties of who owns what.

But when people disagree about who rightly owns what, we must have some method of deciding who is correct, if we are to salvage the possibility of any procedural justice at all; for if, for example, two people each claim ownership of a tract of land and are each wanting to deny the other the use of it, they will find no agreement on who is morally in the right to do so because they disagree about who owns it and so who has any rights over it at all. Such a conflict could be resolved in a creative and cooperative way by dividing up the land into two parcels, one owned by each person, that would permit both people to get the use that they want out of it without hindering the other's use of it. Or the same property can have multiple owners, so long as the uses of the property by those multiple owners do not conflict in context. (Initially, all property is owned by everyone, and in doing so effectively owned by no one; it is the division of the world into those people who own the property and those who don't that constitutes the assignment of ownership to it.)

But if no such cooperative resolution is to be found, and an answer must be found as to which party to the conflict actually has the correct claim to the property in question, I propose that that answer be found by looking back through the history of the property's usage until the most recent uncontested usage can be found: the most recent claim to ownership that was accepted by the entire community. That is then to be held as the correct assignment of ownership, the imperfect duty of this procedural matter, in much the same way that satisfying all appetites constitute the imperfect duty of distributive matters. -

Ciceronianus

3.1kIt’s the other way about. Without property there would be no laws protecting it. — NOS4A2

Ciceronianus

3.1kIt’s the other way about. Without property there would be no laws protecting it. — NOS4A2

If "property" as being used in this thread means "a physical object" or "land" than I suppose that's the case. But I thought something different was being addressed. -

Ciceronianus

3.1kI don't think the law justifies property. — Andrew4Handel

Ciceronianus

3.1kI don't think the law justifies property. — Andrew4Handel

The law doesn't justify anything, for that matter. What's legal isn't necessarily what's right or just.

Property in the sense of physical objects or land merely exists. Property requires no justification.

If we're discussing property in the sense of something someone has a right to, I think legal rights are the only rights which exist for any practicable purpose. Those "rights" people like to refer to as "natural rights" are merely what people think should be legal rights. -

Andrew4Handel

2.5kIf "property" as being used in this thread means "a physical object" or "land" than I suppose that's the case. But I thought something different was being addressed. — Ciceronianus the White

Andrew4Handel

2.5kIf "property" as being used in this thread means "a physical object" or "land" than I suppose that's the case. But I thought something different was being addressed. — Ciceronianus the White

I think they mean property claims. The law formalises peoples claims about things like rights, obligations and ownership. -

Andrew4Handel

2.5kThis is very similar to but subtly distinct from the matter of property rights — of not acting upon something contrary to the will of its owner (including a person's body, which they necessarily own, i.e. necessarily have rights over), which lies in the traditional intersection of perfect duties and procedural justice — because it does not rely on any assignment of ownership, but only on experiential introspection; in much the same way that synthetic a priori knowledge is very similar to but subtly different from analytic a priori knowledge, in that it does not rely on any assignment of meaning to words, but only, again, on experiential introspection. — Pfhorrest

Andrew4Handel

2.5kThis is very similar to but subtly distinct from the matter of property rights — of not acting upon something contrary to the will of its owner (including a person's body, which they necessarily own, i.e. necessarily have rights over), which lies in the traditional intersection of perfect duties and procedural justice — because it does not rely on any assignment of ownership, but only on experiential introspection; in much the same way that synthetic a priori knowledge is very similar to but subtly different from analytic a priori knowledge, in that it does not rely on any assignment of meaning to words, but only, again, on experiential introspection. — Pfhorrest

There is a problem with the status of self ownership.

Slavery has been prolific throughout history. The are dictatorships and theocracies with few if any individuals rights and many women and girls are controlled by male relatives. Children have limited autonomy from parents. Suicide has been illegal in many places throughout time and so on.

So self ownership does not seem to be the default. But it was the basis for Locke's theory of property. He also talked about one's own labours. However one's own labour requires exploitation of the environment and resources and you can question what justifies that.

I think the problem I have with the property is the reification of property as something someone has some kind of metaphysical justified innate claim over rather than a tool for resource distribution. But if there was an infinite amount of resources we would not need the notion of property which is why it seems reliant on scarcity which then means competition and exploitation of limited resources.

We seem to be the only creature that makes such heavy claims on resources and space but I don't think it is sustainable and breeds deep inequality. Or maybe nature is on a self destructive cycle? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kSlavery has been prolific throughout history. The are dictatorships and theocracies with few if any individuals rights and many women and girls are controlled by male relatives. Children have limited autonomy from parents. Suicide has been illegal in many places throughout time and so on.

Pfhorrest

4.6kSlavery has been prolific throughout history. The are dictatorships and theocracies with few if any individuals rights and many women and girls are controlled by male relatives. Children have limited autonomy from parents. Suicide has been illegal in many places throughout time and so on.

So self ownership does not seem to be the default. — Andrew4Handel

When I say that people necessarily own themselves, i.e. necessarily have rights over themselves, I don't mean that those rights are necessarily recognized by all civilizations. To have a right and for your society to enforce that right aren't the same thing.

it was the basis for Locke's theory of property. He also talked about one's own labours. However one's own labour requires exploitation of the environment and resources and you can question what justifies that.

I think the problem I have with the property is the reification of property as something someone has some kind of metaphysical justified innate claim over rather than a tool for resource distribution. — Andrew4Handel

Yeah, I talked about that further down in the same post you're responding to, about how rights depend on the assignment of ownership, and while the former are morally "necessary" (obligatory) inasmuch as they are "a priori" (perfect duties), the latter are morally "contingent" (omissible) inasmuch as they are "a posteriori" (imperfect duties).

It's like how "all bachelors are men" is only a necessary, a priori truth given the usual definition of "bachelor"; but definitions, the assignment of words to meanings, is contingent, and only known a posteriori. If words meant other things, which they could, then different sentences would be necessarily true; and if people owned different things, which they could, then different actions would be morally obligatory.

I actually bolded that connection because it's the most important bit: "The only obligations that can be treated publicly are those phrased in terms of property with assigned ownership, procedural perfect duties; but those in turn depend on the procedural imperfect (and thus omissible) duties of assignment of such ownership." -

Andrew4Handel

2.5kWhen I say that people necessarily own themselves, i.e. necessarily have rights over themselves, I don't mean that those rights are necessarily recognized by all civilizations. To have a right and for your society to enforce that right aren't the same thing. — Pfhorrest

Andrew4Handel

2.5kWhen I say that people necessarily own themselves, i.e. necessarily have rights over themselves, I don't mean that those rights are necessarily recognized by all civilizations. To have a right and for your society to enforce that right aren't the same thing. — Pfhorrest

The act of creating someone undermines their will. We are here through someone else's desires not by autonomy. I think the manner in which life is created goes against a notion of duty. In a sense we are simply surviving. I don't think we can get "ought's" or "duties" from rationality. Notoriously Kant thought we should never lie even to an Axe Murderer.

But there are complex mechanisms now to aid what is only our temporary survival.

Society is like creating a huge factory to crack an egg. It is impressive but the end goal is only temporary survival. The notion of stewardship recognises our temporary interaction with the world and our need to preserve it for others. The only reason I advocate stewardship is because it seems like vandalism to destroy the world if more people are going to inhabit it -

Andrew4Handel

2.5kIt has got to the stage now where a tiny piece of land in London is considered worth millions of pounds and more and more aspects of life are assigned a monetary value. There is intellectual property. You can can own Radio waves and so on. But most wealth is in the hands of a few.

Andrew4Handel

2.5kIt has got to the stage now where a tiny piece of land in London is considered worth millions of pounds and more and more aspects of life are assigned a monetary value. There is intellectual property. You can can own Radio waves and so on. But most wealth is in the hands of a few. -

JerseyFlight

782The question of the "justification" of property is interesting. However, a distinction is in order, private property is not a problem per se, it is a very specific kind of private ownership which constitutes a social problem. The idea of property, in concrete terms, is a strategy to monopolize power. Individuals require space to produce all forms of qualitative existence. To hoard these free spaces (as no libertarian can claim to have engineered them) in the name of idealism is a form of tyranny and control over the species. The question is not where does the power lie, but how does social control work? This is the direction a concerned thinker must go. The justification of private property is first of all an act of social indoctrination and social deprivation. What one thinks of slavery, for example, depends on the cultural mechanisms that have been used to frame it.

JerseyFlight

782The question of the "justification" of property is interesting. However, a distinction is in order, private property is not a problem per se, it is a very specific kind of private ownership which constitutes a social problem. The idea of property, in concrete terms, is a strategy to monopolize power. Individuals require space to produce all forms of qualitative existence. To hoard these free spaces (as no libertarian can claim to have engineered them) in the name of idealism is a form of tyranny and control over the species. The question is not where does the power lie, but how does social control work? This is the direction a concerned thinker must go. The justification of private property is first of all an act of social indoctrination and social deprivation. What one thinks of slavery, for example, depends on the cultural mechanisms that have been used to frame it. -

Hippyhead

1.1kFor the concept of "property" to exist, the only thing required is law — Ciceronianus the White

Hippyhead

1.1kFor the concept of "property" to exist, the only thing required is law — Ciceronianus the White

...and some mechanism for enforcing the law. -

Hippyhead

1.1kA September 2017 study by the Federal Reserve reported that the top 1% owned 38.5% of the country's wealth in 2016. — Wikipedia

Hippyhead

1.1kA September 2017 study by the Federal Reserve reported that the top 1% owned 38.5% of the country's wealth in 2016. — Wikipedia

https://jacobinmag.com/2017/10/wealth-inequality-united-states-federal-reserve -

Andrew4Handel

2.5kI don't think it is necessary to have a concept of property.

Andrew4Handel

2.5kI don't think it is necessary to have a concept of property.

I see no reason why you cannot use resources and have a place of shelter without making the extra claim that you somehow are metaphysical entitled to them to the exclusion of everyone else..

How many wars have been based on asserting claims over territory?

I have no need for things after I die so I recognise what in have now is inevitably temporary and I am in a position of stewardship. -

Gus Lamarch

924For the concept of "property" to exist, the only thing required is law — Ciceronianus the White

Gus Lamarch

924For the concept of "property" to exist, the only thing required is law — Ciceronianus the White

The only thing required in truth - and we all know it - is power... -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI don't think it is necessary to have a concept of property. — Andrew4Handel

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI don't think it is necessary to have a concept of property. — Andrew4Handel

As evident from the participation in this thread, there doesn't seem to be any logical principles to support one thing being the property of another thing.

In logic we use "property" in relation to predication. With predication we describe things through the attribution of properties. In the case of human beings, we might refer to one's actions, and habits to produce a moral description of the person. The habits which are attributed to a person, in relation to presupposed moral principles, supports moral judgement. The act of claiming ownership of objects (what you call "property") can be judged as a habit. Many habits are morally acceptable in moderation, but not in excess. The problem might be to determine an acceptable level.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum